Abstract

This study explores the influences of communal values, empathy, violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs, and classmate’s fighting on violent behaviors among urban African American preadolescent boys and girls. As part of a larger intervention study, 644 low-income 5th grade students from 12 schools completed a baseline assessment that included the target constructs. Boys reported more violent behaviors, and lower levels of empathy and violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs than girls. Path analyses revealed that, after controlling for the positive contributions of classmate’s fighting, violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs were a negative predictor of violent behavior. Communal values had a direct negative relationship with violence for boys, but not girls. Both communal values and empathy were associated with less violent behavior through positive relationships with violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs. For girls, classmate fighting had an indirect positive association with violent behavior through its negative relationship with violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs. Findings are discussed in terms of implications of basic and applied research on violence among African American youth.

Keywords: Protective factors, Violence prevention, African American culture, Self-efficacy beliefs

Introduction

Low-income urban African American youth continue to be disproportionately represented among both perpetrators and victims of various forms of violence. Males are consistently found to demonstrate more violent behaviors than females, although rates for girls are rising (CDC 2004; Clubb et al. 2001; Tolan et al. 2003; Valois et al. 2002). While comprising only 15% of the US youth population, African American youth account for over half the arrests for homicide nationwide (Snyder and Sickmund 1999). Incidents of non-fatal assaults (physical fights, shooting at, cutting, or stabbing) also are higher among African American youth than youth of other ethnic backgrounds (Kann et al. 2000). In addition, these young people are at serious risk for involvement in other violence-related behaviors, such as threatening people and carrying weapons (CDC 2004; Clubb et al. 2001). Data from 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS) indicated that roughly 40% of African American high-school students had been involved in a physical fight and 17% reported carrying a weapon. In a recent multi-site survey of minority middle school students, Clubb et al. (2001) found that 67% of African American respondents had been involved in some type of violence in the 3 months prior to the survey. Fifty percent of males and 40% of females indicated that they had threatened to beat someone up, with half the males and one third of the females actually fighting. Importantly, 40% of those that reported fighting also carried a weapon.

The existing literature on violence suggests that several factors, but especially negative peer influences, can place youth at serious risk for violent behaviors (Dishion et al. 1995; Henry et al. 2001). In contrast, the research literature on protective factors is fairly sparse (Herrenkohl et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2001). Basic research on protective factors among African American youth is important since a substantial segment of these young people manage to avoid engaging in serious violent behavior, despite chronic exposure to multiple environmental risks. Insight into factors that buffer against violence involvement is also useful to those interested in offering effective violence interventions in this population.

Protective Factors Against Violence Involvement: Toward a Cultural Model

There is some evidence that individual and social factors can protect youth from involvement in violence and related behaviors. For example, intellectual, attitudinal, and social cognitive factors have been associated with lower levels of aggression and violence (Bandura 2001; Coie and Dodge 1998; Herrenkohl et al. 2003; Whaley 2003). Further, the degree of bonding and engagement with social institutions like family, school, and church, can help buffer youth from negative peer influences, and subsequent problem behaviors, including violence (Clubb et al. 2001; Herrenkohl et al. 2003; Tolan et al. 2003).

In addition, there has been a growing interest in the ways in which race-related and cultural factors might serve as protective and promotive influences in this population (Caldwell et al. 2004; Jagers 1996; Jagers and Mock 1993; Jagers et al. 2003; Ward 1995). However, we agree with Caldwell et al that there continues to be a need to systematically study these sociocultural influences as psychosocial or social contextual factors related to violent behavior. Toward this end, this investigation explores the associations among the cultural theme of communalism, empathy, violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs, and violent behavior among African American youth.

The African American experience comprises various and diverse cultural themes and influences (Boykin 1983). Rather than assuming cultural homogeneity in this population, it seems more reasonable to expect individual differences in the degree to which African Americans are exposed to and embrace these themes (Turiel 1998). Communalism is one of several cultural themes thought to shape the contemporary African American experience (Boykin 1983). A communal orientation connotes placing a premium on social responsibilities and a commitment to promotive interdependence. Communalism is not unique to African Americans and like the related cultural psychology construct of collectivism, it has been attributed to, and studied among various ethnic groups (Jagers and Mock 1995). Previous research on communalism has indicated that school-aged children positively endorse this value orientation, with no mean differences based on gender or grade level (Jagers 1996, 1997; Jagers and Mock 1993, 1995; Jagers et al. 1997).

A communal value orientation can be expressed in terms of relationships with family, peers, community institutions (e.g., school, church), and/or same race others (Jagers and Mock 1995; Jagers et al. 2003). This suggests that communal values are consistent with the tenants of the Nguzo Saba (Karenga 1980), which emphasize the primacy of family, community and racial group for African Americans.

Ward (1995) has posited that communal values prescribe a morality of caring that has relevance for preventing Black-on-Black violence in urban communities. There is some evidence that a communal orientation is associated with positive outcomes among children and youth. For example, a communal orientation was found to be associated with cooperative academic attitudes, empathy (Humphries et al. 2000; Jagers 1997; Jagers and Mock 1993), related characteristics like moral maturity (Humphries et al. 2000) and pro-social interpersonal values such as helpfulness and forgiveness (Jagers and Mock 1995).

Empathy was of interest in this study for several reasons. Previous research has shown communal values to be positively associated with empathy, an other-oriented emotion that implies the ability to recognize emotional cues, take another’s perspective, and to be emotionally responsive to another’s emotional state (Sams and Truscott 2004). Further, there has been considerable support for a negative association between empathy and aggression/violence among children (Feshbach 1975; Kaukianen et al. 1999). The few studies that have looked at adolescents lend support to this pattern of findings (Sams and Truscott 2004; Kingery et al. 1996).

In addition, recent research has suggested that perceived self-regulatory efficacy may play an important role in avoiding or limiting violent behavior (Caprara et al. 2002). Generally speaking, perceived self-efficacy refers to domain-specific beliefs about capabilities to organize affective, cognitive, motivational and choice processes, exert control over performance, and achieve goals in particular situations (Bandura 2001). In studies with European adolescents, violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs have been found to impact on pro-social and antisocial behaviors (Caprara et al. 1998, 2002). Both a communal orientation and empathy are consistent with violence avoidance efficacy beliefs. Communal values would be supported by confidence in one’s capacity to resolve interpersonal conflict situations without resorting to violence. Empathy would be an essential ingredient of violence avoidance efficacy since the capacity to eschew violence often requires accurate and timely recognition and response to relevant emotional cues.

As noted earlier, data consistently reflect lower rates of violent behavior among females. However, the gap in these reported data has been decreasing. In recent years, research on females and violent behavior has expanded considerably. Still, more research in this area is required (Rappaport and Thomas 2004). Gender comparative studies of violent behavior have tended to show no significant model variance by gender, although differences in magnitude of effects have been noted (Gorman-Smith and Loeber 2005; Fleming et al. 2002). In this current work, we are able to contribute to that growing body of literature by providing gender comparison in our analyses.

The Present Study

This study explores the relationships among communal values, empathy and violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs and their influences on violent behaviors among urban African American fifth graders. The influence of exposure to peer violence was considered given its importance to the development of violent behavior. In this study, there was an interest in the contributions of fighting among classmates to children’s violent behavior. Among preadolescents, classmates’ fighting can prompt violent behavior proactively through modeling and positive social reinforcement. It also can spark reactive violence since there may be an increased need for children to defend themselves.

We employ baseline data from a culturally grounded preventive intervention program (Flay et al. 2004) to provide research relevant to culture theory, research, and action. Initial research findings revealed the program reduced substance use, unsafe sex and violence for boys, but not for girls (Flay et al. 2004). Subsequent analyses revealed peer factors mediated intervention effects on boy’s violent behaviors (Ngwe et al. 2004).

This study was intended as a first step in understanding the psychosocial mechanisms through which a communal value orientation, the focal cultural construct of the Aban Aya Youth Project (AAYP) intervention, might impact on risk behaviors. It was assumed that the proposed relationship between a communal value orientation and violent behaviors occurs through associations with empathy and violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs. Possible gender differences are of interest since an examination of putative protective factors might shed light on why boys tend to display more violent behaviors than girls.

It was hypothesized that the relationship between communal values and violent behavior was indirect, occurring through violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs. Empathy was hypothesized to have a direct relationship with violent behavior, but also to have an indirect association through violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs. No gender specific hypotheses were offered, although there was an interest in exploring possible difference in patterns and/or magnitude of associations.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were 644 fifth grade students enrolled in 12 Midwestern elementary schools during the 1994–1995 academic years. The mean age of participants was 10.8 years at baseline. Roughly half of the sample was male (46.5%) and approximately 77% were eligible for free and reduced priced lunch programs. Less than half (47%) of the participating students lived in two-parent households.

Measures

Aban Aya Youth Project questionnaires were taken or adapted from other well-researched measures and questionnaires (Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS), National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)). Measures were refined based on input from focus groups and pilot testing with youth and parents living in high-risk communities.

Communal Values

Consistent with the Nguzo Saba principles that informed AAYP, in this study we focused on youth ratings of the importance of four items: cooperating with others, thinking about family, learning about African American culture and history, and keeping the neighborhood clean. Each item was rated on a five point scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important). Item-scale correlations ranged from .32 to .46. A coefficient alpha of .63 was yielded for the present sample.

Empathy

Five items derived from the Bryant (1982) empathy scale and the Davis (1983) empathic concern subscale were used to address affective and cognitive aspects of empathy. Some sample items include: “When I see someone getting used I feel badly.”

“I try to think before I do something that could hurt someone else.” Items were responded to on a three-point scale ranging 0 (no)–2 (yes). Item-scale correlations ranged from .34 to .47. An alpha coefficient of .62 was generated for the present sample.

Violence Avoidance Self-efficacy Beliefs

Three items were used to assess violence avoidance efficacy beliefs. Children indicated how sure they were that they could: stay away from a fight, seek help instead of fighting, and keep from getting into a fight. Response options ranged from 1 (definitely cannot) to 5 (definitely can). Item-scale correlations ranged from .57 to .69. An alpha coefficient of .80 was generated for these items.

Number of classmates who fight was assessed using a single item that asked participants to indicate how many children in their grade had gotten into a physical fight this year. Response options ranged from 1 (none of them) to 5 (all of them).

Violent behavior was assessed using 8 questions adapted from the 1992 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (Flay et al. 2004). As the YRBSS was originally developed for high school students, questions were modified to reflect the earlier stages of violence that 5th–8th grade children might engage in. Children were asked if they had ever: (a) threatened to beat up someone; (b) threatened to cut, stab or shoot someone; (c) been in a physical fight; (d) carried a gun; (e) shot at someone; (f) carried knife or razor; and (g) cut or stabbed someone. Response choices were a simple dichotomy (0 = no; 1 = yes) for the lifetime involvement questions (i.e., Have you ever …?). Item-scale correlations ranged from .20 to .40. Cronbach’s α coefficient for this sample was .58.

Data Collection Procedures

Data for this study were gathered as part of the baseline assessment in the context of a culturally grounded preventive intervention designed to reduce the risk for unsafe sex, substance use and violence (Flay et al. 2004). Twelve schools were randomly assigned to receive: (1) a classroom social development curriculum condition, (2) a school/family/community condition, or (3) an attention-placebo control.

All 5th grade children were recruited to participate in the study. Prior to beginning data collection, each child’s parent/guardian was informed about the study and given the option to have their child excluded from the data collection process. No children were withdrawn from the study. In addition, at the beginning of each survey administration session, the children were reminded that they had the option not to answer any question(s) that made them feel uncomfortable.

The survey questionnaire was administered to all students in their primary or “homeroom” classrooms by a three-member data collection team. All members were trained on survey administration procedures and at least one member had classroom management experience. The classroom teacher remained in the room, as required by Illinois law, but they did not participate in survey administration, instead remaining at their desk. One team member read aloud the survey questions to the participants, a second team member monitored entry and exiting of visitors and late arriving students, and the third member responded to individual questions children had regarding the survey. Participants were given a 5–10 min break about midway through the survey, which on average took approximately 2 h to complete.

Analytic Strategy

The t-tests were calculated to assess gender differences on mean scores for violence and predictor variables. A bivariate correlation matrix including all variables of interest was then generated to examine relationships among predictor variables and relationships between predictor variables and violence. Correlation coefficients were also calculated for males and females separately to determine whether relationships among the variables differed according to gender. Based on these analyses, path models were generated to test associations between violence and the predictor variables for boys and girls. Specifically, we tested the direct effects of communal values, empathy, and violence avoidance self-efficacy on violence, plus the effects of communal values and empathy on violence mediated through violence avoidance self-efficacy, and adjusted for the influence of classmates fighting on violence. This model also examined the association between communal values and empathy. Model fit was assessed by examining chi-square statistics, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A non-significant chi square statistic, a chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio of less than 2 and CFI above .90 are all indicative of a good fitting model. RMSEA values of .05 or less also suggest a good model fit to the data (Tabachnick and Fidell 1996). The R2 indicates the variance in violent behavior accounted for by the model. The associations between variables were assessed by examining standardized path coefficients.

Results

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether there were significant differences in violence or predictor variables based on intervention condition or gender. The only difference between conditions was that boys in the School/Community condition reported higher levels of violence than those in the Social Development Curriculum condition. Table 1 presents gender differences on violence and predictor variables. Boys reported significantly higher rates of violent behavior (M = 2.5, SD = 1.4) than girls (M = 1.7, SD = 1.3; P < .001). Boys also expressed lower rates of empathy (M = 1.41, SD = 0.48) and violence avoidance self-efficacy (M = 3.00, SD = 1.11) relative to girls (M = 1.55, SD = 0.44, P < .001; M = 3.17, SD = 0.98, P < 0.05, respectively). No gender differences were found in communal values or the number of classmates who fight.

Table 1.

Gender differences on violence and predictor variables

| Males

|

Females

|

t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Violent behavior | 2.50 | 1.50 | 1.70 | 1.30 | 8.57*** |

| Predictor variables | |||||

| Communal values | 2.49 | 0.75 | 2.49 | 0.77 | ns |

| Empathy | 1.41 | 0.48 | 1.55 | 0.44 | −3.69*** |

| Violence avoidance efficacy | 3.00 | 1.11 | 3.17 | 0.98 | −2.13* |

| Classmate fighting | 1.60 | 1.81 | 1.56 | 1.09 | ns |

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001

Table 2 presents bivariate correlation coefficients among predictor variables and violence. Communal values, empathy, and violence avoidance self-efficacy were significantly associated with each other. Correlation coefficients ranged from ρ = 0.21 (P < .01) to ρ = 0.23 (P < .001). Violence avoidance self-efficacy was negatively associated with the number of classmates who fight (ρ = −0.14, P < .01). Communal values (ρ = −0.14, P < .01) and violence avoidance self-efficacy (ρ = −0.29, P < .001) were negatively associated with violence, while number of classmates who fight was positively associated with violence (ρ = 0.27, P < .001). There was no association between empathy and violence.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of predictor variables and violence

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Communal values | – | ||||

| 2. Empathy | .21** | – | |||

| 3. Violence avoidance efficacy | .22** | .23*** | – | ||

| 4. Classmates fighting | .01 | .00 | −.14* | – | |

| 5. Violent behavior | −.14** | −.08 | −.29*** | .27*** | – |

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001

Bivariate correlations were generated to examine whether patterns might vary as a function of gender. Table 3 presents these relationships for boys and girls separately. For the most part, similar patterns of relationships among variables were observed for boys and girls. For both boys and girls, communal values, empathy, and violence avoidance self-efficacy were significantly associated with each other. There were positive associations between the fighting of classmates and violence, while communal values and violence avoidance self-efficacy were negatively associated with violent behavior. For girls only, however, violence avoidance self-efficacy was negatively associated with the number of classmates who fight. No significant relationships between empathy and violence emerged for boys and girls. Univariate and bivariate analyses suggested the benefit of conducting separate multivariate analyses for boys and girls.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix by gender

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Communal values | – | .30*** | .19** | .01 | −.17** |

| 2. Empathy | .13* | – | .15** | .05 | −.03 |

| 3. Violence avoidance efficacy | .25*** | .31*** | – | .08 | – |

| .27*** | |||||

| 4. Classmates fighting | .02 | .07 | – | ||

| .20*** | – | .26*** | |||

| 5. Violent behavior | −.12* | −.05 | – | ||

| .28*** | .29*** | – |

Note. Top diagonal = correlation coefficients among boys. Bottom diagonal = correlation coefficients among girls

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001

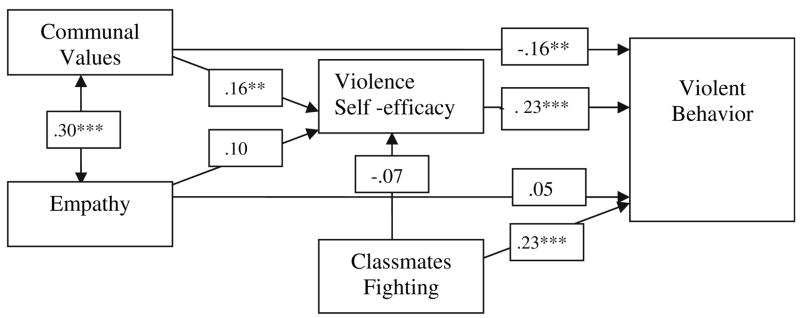

Figure 1 depicts the path model constructed to determine associations between the independent variables and violence. A non-significant chi-square χ2 (2, 641) = .14, P = .93 (χ2/df ratio = .069) and fit indices (CFI = 1.00, RSMEA = .000) indicated that the model fit the data for the combined sample and the overall model accounted for 14% of the variance in violent behavior scores. After controlling the significant contribution of classmates fighting (β = 0.22, P < .001), communal values (β = −0.08, P < 0.05) and violence avoidance self-efficacy (β = −0.24, P < .001) emerged as negative predictors of violent behavior. It was noteworthy that classmate fighting had a negative association with violence avoidance efficacy (β = −0.13, P < 0.05). However, both communal values (β = 0.17, P < .001) and empathy (β = 0.20, P < .001) were significant positive predictors of violence avoidance self-efficacy. Communal values also were a positive correlate of empathy (β = 0.21, P < .001).

Fig. 1.

Model summary with standardized estimates (Total). R2 (violent behavior) = .14; χ2 = .139, df = 2, P = .933, χ2/df = .069; RMSEA = .000 (.000, .022); CFI = 1.00; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

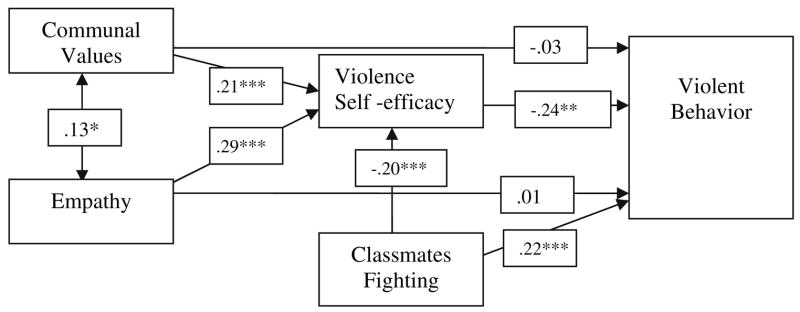

Figure 2 displays path model for boys, which accounted for 15% of the variance in violence scores. The model was not significant for boys χ2 (2, 301) = .84, P = .66 (χ2/df ratio = .42), with fit indices (CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .00) indicating a good fit for the data. As in the overall model, after adjusting for the significant impact of classmate fighting (β = 0.23, P < .001), communal values (β = −0.16, P < .01) and violence avoidance self-efficacy (β = −0.23, P < .001) had direct negative associations with boy’s violent behavior. Communal values was a significant predictor of violence avoidance self-efficacy (β = 0.16, P < .01) as well as empathy (β = 0.30, P < .001).

Fig. 2.

Model summary with standardized estimates (Boys). R2 (violent behavior) = .15; χ2 = .836, df = 2, P = .658, χ2/df = .418; RMSEA = .000 (.000, .088); CFI = 1.00; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

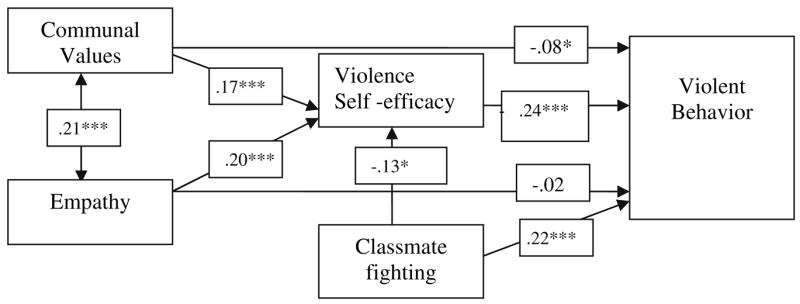

The model for girls is shown in Fig. 3. The chi-square statistic for the model was not significant, χ2 (2, 335) = 2.17, P = .06 (χ2/df ratio = 1.1), and the fit indices indicated acceptable model fit (CFI = 0.998, and RSMEA = .02). As in the two previous analyses, classmate fighting also was a negative predictor of girl’s violent behavior (β = 0.16, P < .001). In addition, violence avoidance self-efficacy (β = −0.26, P < .001) had a direct negative association with violent behavior. Classmate fighting contributed negatively to girl’s violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs (β = −0.29, P < .001), while both communal values (β = 0.21, P < 0.0001) and empathy (β = 0.29, P < .001) were positive predictors of such beliefs. In addition, communal values was positively associated with empathy (β = 0.13, P < 0.05). The model accounted for 14% of the variance in girl’s violence scores.

Fig. 3.

Model summary with standardized estimates (Girls). R2 (violent behavior) = .14; χ2 = 2.178, df = 2, P = .062, χ2/df = 1.089; RMSEA = .016 (.000, .111); CFI = .998; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

Discussion

This study examined several individual factors thought to protect African American youth from engaging in violent behaviors, with a particular interest in communal values. There appear to be individual factors, which can help limit violent involvement, even in the context of negative peer influences. Consistent with recent research on self-regulatory beliefs among European youth (Caprara et al. 1998, 2002), violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs emerged as an important negative predictor of violent behavior for both girls and boys in this sample. The more confident these young people were that they could successfully seek help or walk away from violent situations the less violent behavior they reported. Classmate fighting impacted negatively on girl’s beliefs in their ability to avoid violence, however.

In addition, communal values were negatively associated with the self-reported violent behavior of boys. The more participants valued promotive interdependence with family, community, and racial group, the less they tended to engage in such behaviors. It was curious, however, that communal values did not have a direct association with violent behaviors among girls, though boys and girls did not differ significantly on this measure. Perhaps social commitments or contracts are more important for limiting violent behavior for boys more than for girls (Gilligan and Attanucci 1988).

Empathy also contributed to violence avoidance efficacy beliefs. This association seemed to be stronger among girls than boys. Attention to, and understanding of others emotional states apparently allows for increased confidence that one can negotiate violent situations without fighting which, in turn, reduces violent behavior. This pattern of findings is consistent with the notion of a morality of caring, especially among girls (Gilligan and Attanucci 1988; Zahn-Waxler and Polanichka 2004; Ward 1995). It was interesting, however, that no direct relationship between empathy and violent behaviors emerged. Such a relationship was expected based on the research literature.

The indirect associations of communal values and empathy with violence through violence avoidance self-efficacy beliefs suggest that other-oriented sensibilities may be necessary, but not sufficient to effectively limit violent behavior. It is essential that youth also be confident in their ability to negotiate potentially violent situations. This finding has important implications for preventive interventions. It points to the potential benefit of infusing communal values into violence prevention programs aimed at urban African American boys and girls. Framing prevention efforts in terms of the importance of family, community and/or racial group can reduce violence in its own right, but its most critical function may be the priming of essential social and emotional competencies, especially self-efficacy beliefs. It may be that there are gender differences in the specific mechanisms for this, however (Gorman-Smith and Loeber 2005). In this connection, it is important to better understand how communal values fit within contemporary African American culture. For example, racial identity, socioeconomic status, community context (urban/rural, racially homogeneous/heterogeneous), and geographic location (region of the country) might be important correlates of the expression of communalism and other cultural orientations among boys and girls.

There were important limitations to this study that need to be acknowledged. For example, this cross-sectional study used only 5th grade students. Hence, it provided no insight into whether empathy, communal values, and violence avoidance self-efficacy preceded violence, or whether violence preceded empathy, communal values, and violence self-efficacy. While we have speculated about the developmental course of cultural orientations and social-emotional competencies, longitudinal research studies would help document the trajectory and relevant socialization processes of these psychological characteristics.

The reliance on youth self-reports also was a limitation of this study. Data from multiple informants is preferred in order to improve reliability of assessments, especially for problem behaviors like violence. Teacher and peer data might be most valuable in this regard.

Finally, future research should examine possible intervention effects on communal values, empathy and violence avoidance efficacy as they relate to the development of violent behavior among girls and boys. If these protective factors cannot be cultivated to help delay the onset and/or slow the growth of violent behavior then one might question the functional significance of this line of research for violence prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

The Aban Aya Project was supported by grants to Brian R. Flay (P. I.) from the Office of Minority Health administered by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (U01HD30078) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA11019). Support for secondary analysis and manuscript preparation were provided to the first author by grants from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities (P60-MD002217-01) and National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA12390).

References

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW. The academic performance of Afro-American children. In: Spence JT, editor. Achievement and achievement motives. San Francisco, CA: Freeman; 1983. pp. 321–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant BK. An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Development. 1982;53:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Kohn-Wood LP, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Chavous TM, Zimmerman MA. Racial discrimination and racial identity as risk or factors for violence behaviors in African American young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33:91–105. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014321.02367.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Regalia C, Bandura A. Longitudinal impact of perceived self-regulatory efficacy on violent conduct. European Psychologist. 2002;7:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Scabini E, Barbaranelli C, Pastorelli C, Regalia C, Bandura A. Impact of adolescents’ perceived self-regulatory efficacy on familial communication and antisocial conduct. European Psychologist. 1998;3:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Violence – related behaviors among high school students – United States, 1991–2003. MMWR. 2004;53:651–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb PA, Browne DC, Humphrey AD, Schoenbach V, Meyer B, Jackson M The RSVPP Steering Committee. Violent behaviors in early adolescent minority youth: results from a “middle school youth risk behavior survey”. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2001;5:225–235. doi: 10.1023/a:1013076721400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 3. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW, Crosby L. Antisocial boys and their friends in early adolescents: Relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional process. Child Development. 1995;66:139–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feshbach N. Empathy in children: Some theoretical and empirical considerations. The Counseling Psychologist. 1975;5:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY The Aban Aya Investigators. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: A randomized trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Oxford ML, Harachi TW. A test of generalizability of the social development model across gender and income groups with longitudinal data from the elementary school developmental period. Journal of Quantitaive Crimonology. 2002;18:423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C, Attanucci J. Two moral orientations: Gender differences and similarities. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1988;34:223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Loeber R. Are developmental pathways in disruptive behaviors the same for girls and boys? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Longitudinal family and peer group effects on violent and non-violent delinquency. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology. 2001;30:172–186. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Chung I, Guo J, Abbott RD, Hawkins JD. Protestive factors against serious violent behavior in adolescence. A prospective study of aggressive children. Social Work Research. 2003;27:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries M, Parker B, Jagers RJ. Predictors of moral maturity among African American children. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ. Culture and problem behaviors among innercity African American youth: Further explorations. Journal of Adolescence. 1996;19:371–381. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ. Afrocultural integrity and the social development of African American children: Some conceptual, empirical, and practical considerations. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 1997;16:7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Mock LO. Culture and social outcomes among innercity African American children: An Afrographic exploration. Journal of Black Psychology. 1993;19:391–405. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Mock LO. The Communalism Scale and collectivistic-individualistic tendencies: Some preliminary findings. Journal of Black Psychology. 1995;21:153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Mattis JS, Walker K. A cultural psychology framework for the study of morality and African American community violence. In: Hawkins DF, editor. Violent crime: Assessing race and class differences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Smith P, Mock LO, Dill E. An Afrocultural social ethos: Component orientations and some social implications. Journal of Black Psychology. 1997;23:328–343. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, Kolbe LJ, State and Local YRBSS Coordinators. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 1999. MMWR. 2000;49(SS05):1–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karenga M. Kawaida theory: An introductory outline. Inglewood, CA: Kawaida Publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukiainen A, Bjoerkqvist K, Lagerspetz K, Oesterman K, Salmivalli C, Rothberg S, Ahlbom A. The relationship between social intelligence, empathy and three types of aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1999;25:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kingery PM, Biafora FA, Zimmerman RS. Risk factors for violent behaviors among ethnically diverse urban adolescents. School Psychology International. 1996;17:171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ngwe JE, Liu LC, Flay BR, Segawa E Aban Aya Investigators. Violence prevention among African American adolescent males. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28(supplement 1):s24–s37. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.s1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport N, Thomas C. Recent research findings on aggressive and violent behavior in youth: Implications for clinical assessment and intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:260–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sams DP, Truscott SD. Empathy, exposure to community violence and use of violence among urban, at risk adolescents. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2004;33:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Flay BR, Bell CC, Weissberg RP. The protective influence of parents and peers in violence avoidance among African American youth. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2001;5:245–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1013080822309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN, Sickmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 1999 national report. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U. S. Department of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3. New York: Harper Collins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. The developmental ecology of urban males’ youth violence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:274–291. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of morality. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 863–932. [Google Scholar]

- Valois RF, MacDonald JM, Bretous L, Fischer MA, Drane JW. Risk factors and behaviors associated with adolescent violence and aggression. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26:454–464. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JV. Cultivating a morality of care in African American adolescents: A culture-based model of violence prevention. Harvard Educational Review. 1995;65:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cognitive-cultural model of identity and violence prevention for African American youth. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 2003;129:101–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Polanichka N. All things interpersonal: Socialization and female aggression. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 48–68. [Google Scholar]