Abstract

Cancer cells acquire drug resistance as a result of selection pressure dictated by unfavorable microenvironments. This survival process is facilitated through efficient control of oxidative stress originating from mitochondria that typically initiates programmed cell death. We show this critical adaptive response in cancer cells to be linked to uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2), a mitochondrial suppressor of reactive oxygen species (ROS). UCP2 is present in drug-resistant lines of various cancer cells and in human colon cancer. Overexpression of UCP2 in HCT116 human colon cancer cells inhibits ROS accumulation and apoptosis post-exposure to chemotherapeutic agents. Tumor xenografts of UCP2-overexpressing HCT116 cells retain growth in nude mice receiving chemotherapy. Augmented cancer cell survival is accompanied by altered N-terminal phosphorylation of the pivotal tumor suppressor p53 and induction of the glycolytic phenotype (Warburg effect). These findings link UCP2 with molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance. Targeting UCP2 may be considered a novel treatment strategy for cancer.

Keywords: Uncoupling protein-2, mitochondria, apoptosis, p53, chemoresistance

INTRODUCTION

Cancers are often exposed to adverse conditions such as nutrient limitation, ischemia, hypoxia, host defense mechanisms and anti-cancer therapy. Cancer cells typically respond to these stimuli by increased abundance of ROS resulting in oxidative stress (1). In this complex interplay, ROS promote further genomic instability and stimulate signaling pathways of cellular growth and proliferation. Paradoxically, ROS may also initiate cell death pathways if present in excessive amounts (2, 3). The ability of cancer cells to regulate ROS levels greatly contributes to autonomous growth, evasion of apoptosis, and other hallmarks of adaptation associated with chemoresistance (4, 5). A better understanding of how oxidative stress is controlled by cancer cells is therefore essential to identifying new molecular targets for the treatment of cancer.

Mitochondria are the primary source of metabolically derived ROS (6). Substrate oxidation by mitochondrial respiration generates a proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane that establishes the electrochemical potential (Δψm). The energy contained within Δψm can be either used for ATP synthesis (oxidative phosphorylation) or dissipated as heat that is mediated via proton leak in a process termed uncoupling (7). Elevated Δψm levels impede rapid flow of electrons along the respiratory chain, facilitating escape of more electrons and formation of superoxide, the primary mitochondrial ROS (6). Since proton leak decreases Δψm and the rate of superoxide production, mitochondrial uncoupling is a principal mechanism in the regulation of oxidative stress (8, 9). Accordingly, uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2), a widely distributed member of the anion carrier protein superfamily located in the mitochondrial inner membrane, is the major regulator of mitochondrial ROS (9, 10).

UCP2 expression correlates with neoplastic changes in human colon cancer (11), and drug-resistant sub-lines of various cancer cells also exhibit increased levels of UCP2, lower Δψm, and reduced susceptibility to oxidative damage (12). Overexpression of UCP2 in HepG2 human hepatoma cells lowers intracellular ROS levels and attenuates apoptosis induced by various challenges (13). Thus, while UCP2 is a marker of chemoresistance, expression of this mitochondrial protein may facilitate cancer cell adaptation to oxidative stress. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which increased UCP2 expression may promote cancer cell survival are not known and have been examined here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

Human colon cancer cell lines HCT116, HT29, DLD1, and CaCo2 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. p53−/− HCT116 cells and their wild type isogenic cell line were a generous gift of Dr. Bert Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University. Cells were cultured in McCoy’s modified medium (HCT116, HT29), RPMI-1640 (DLD1), or Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (CaCo2), all supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (20% in case of CaCo2), 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were kept in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Plasmids and Cell Transfection

For UCP2 overexpression experiments, human spleen total RNA (Ambion) was reverse transcribed and full length human UCP2 cDNA was amplified by PCR using sequence-specific primers (forward: 5′-TACAGGTACCATGGTTGGGTTC-3′, reverse: 5′-CTAAGCTTTCAGAAGGGAGCCTCT-3′, containing restriction sites for KpnI and HindIII, respectively (underlined). The double-digested cDNA was inserted into pcDNA 3.1/Zeo (−) using the rapid DNA ligation kit (Roche). Successful ligation of the full-length hUCP2 was confirmed by sequencing (W.M. Keck Facility, Yale University). The same plasmid was used to generate a standard curve in the real-time PCR assay. The full-length human TATA-box binding protein (TBP) was cloned by similar technique (forward primer: 5′-AGAACAACAGCCTGCCACCT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TTACGTCGTCTTCCTGAATCC-3′) and subsequently inserted into the pCR 2.1 vector. HCT116 cells (5×106 cells per reaction) were transfected by nucleofection (Amaxa Biosystems) using 2 μg plasmid following the manufacturer’s instructions. The UCP2 overexpressing HCT116 stable cell line was generated by using 10 μg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen) in the culture medium for several passages and colonies raised from a single cell were analyzed for UCP2 expression by Western blotting.

Chemicals and UV Irradiation

Camptothecin (CPT), doxorubicin-hydrochloride, etoposide, carbonylcyanide-4-trifluoro-methoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), oligomycin, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, MG132 (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-Ala) and routine chemicals were ordered from Sigma unless otherwise specified. Camptothecin stock solution (2.5 mM) was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Doxorubicin stock solution (2 mg/ml) was prepared in water. Etoposide stock solution (50 nM) was prepared in methanol. FCCP (40 mM) was dissolved in ethanol and kept at −20°C until usage. Irinotecan (CPT-11) was obtained from Pfizer and it was dissolved in physiological saline (20 mg/ml). Cells were exposed to UV irradiation essentially as described elsewhere (14). Briefly, cells were washed three times with PBS, which was then removed and the plates were irradiated for 15 min with 40 J/m2 intensity on ice, using FB-UVXL-1000 cross-linker (Fisher) followed by overnight incubation at 37°C. Cell death was assessed by cell cycle analysis.

Real-time PCR

The PARIS kit (Ambion) was used to isolate total cellular RNA and protein from the samples following the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA was reverse transcribed using First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) and 5 ng cDNA was amplified with sequence-specific primers using iCycler iQ Multi-Color Real Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Serial dilutions of the human UCP2, TBP plasmids were used to create standard curves. Thermal cycling conditions involved 45 cycles, with denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s using 0.4 μM of intron-spanning primers (UCP2, forward: 5′-CTCCTGAAAGCCAACCTCAT-3′, reverse: 5′-CCCAAAGGCAGAAGTGAAGT-3′; TBP, forward: 5′-CACGAACCACGGCACTGATT-3′ reverse: 5′-TTTTCTTGCTGCCAGTCTGGAC-3′.) Samples were run in triplicates, normalized using their TBP mRNA content as endogenous reference, and data were expressed in arbitrary units as relative abundance of UCP2 mRNA over TBP.

Mitochondrial Isolation and Fractionation

Mitochondria were isolated using standard protocol (15). Purified mitochondria were either homogenized in cell disruption buffer (PARIS Kit, Ambion) and snap-frozen for further use in immunoblot analysis or further fractionated using the previously described digitonin/alkaline treatment (16). Briefly, 100 μl of purified mitochondria were dissolved in 500 μl of digitonin solution (1.2 mg/ml). After incubation on ice for 25 min, the suspension was centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min to generate mitoplasts, which consisted of the mitochondrial inner membranes and the matrix. The supernatant contained the intermembrane space fraction and outer membrane. For alkaline treatment, mitochondrial pellets were washed and resuspended in freshly prepared 0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 11.5 and subsequently incubated at 0°C for 30 min. The membrane fraction was recovered by centrifugation at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant represented the soluble fraction of the mitochondria. Mitoplasts and mitochondrial membranes were reconstituted in cell disruption buffer.

Antibodies and Immunoblot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared in cell disruption buffer (PARIS Kit, Ambion) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). For the detection of phosphoproteins, we used the following lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1 % NP-40, 10 % glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM sodium fluoride, supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce). Protein extracts were fractionated by 12-15% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (PerkinElmer). Immunoblots were performed using primary antibodies against the following: UCP2 (C-20, Santa Cruz), p53, caspase-3 (full), caspase-3 (cleaved), cytochrome c, cytochrome c oxidase, Bcl-XL, and PUMA-alpha. Secondary antibodies were conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and immunoblots detected by ECL (PerkinElmer). Equal loading was confirmed using primary antibodies against beta-actin (whole cell lysates) or against cytochrome c oxidase IV (mitochondrial preparations).

Cell Growth and Cell Cycle Analysis

Numbers of viable cells were determined by use of the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo). For cell cycle analysis, 2×106 cells were collected and resuspended in 1 ml PBS then fixed in equal amount of ice-cold 100% ethanol overnight. Next day, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then centrifuged at 200g for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1ml of freshly prepared staining solution (0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS, 0.2 mg/ml DNAse-free RNAse A (Sigma) and 20 μg/ml PI (Roche). The cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes and transferred to flow cytometer (FACSort, Becton Dickinson) immediately. CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) was used for data acquisition and ModFit LT software (Verity Software House) for data analysis.

Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was measured qualitatively using the lipophilic fluorescent probe, 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′,-tetraethyl-benzimidazolycarbocyanine chloride (JC-1, Sigma). Cells were cultured in 96-well plates, washed with PBS, and incubated with 6 μM JC-1 for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed with TRIS-buffered saline and JC-1 fluorescence was immediately measured in a SpectraMax M5 spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices). The ratio of red (530 nm) to green (590 nm) fluorescence of JC-1 was calculated for each well. To control experimental conditions, FCCP (50 μM) and oligomycin (10 μM) were used to dissipate and increase Δψm, respectively. Each condition was reproduced in at least 6 wells for each experiment.

Measurement of Whole Cell Oxygen Consumption

Cells were harvested and resuspended in medium containing 125 mM NaCl, 5.2 mM KCl, 1 mM Na2PO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM dextrose, and 10 mM HEPES. Batches of 5×106 cells were placed in the chamber of a Digital Model 10 polarography apparatus equipped with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Rank Brothers) and oxygen consumption was measured for up to 15 min until the medium was depleted of oxygen according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Initial oxygen content was calculated to be 0.20625 mM/l based on temperature, altitude, and osmolarity of cell medium. Electrode potentials were recorded on a computer via an interface system using Pico Log Recorder (Pico Technology). The rate of oxygen consumption was calculated for each run, and each condition was repeated at least in triplicate.

Biochemical Assays

Cellular ATP content was measured with ATPlite kit (Perkin Elmer). Lactate levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by Lactate Assay Kit (BioVision). Both ATP and lactate levels were normalized to viable cell numbers.

DNA Fragmentation Assay

DNA fragmentation was assessed by the accelerated apoptotic DNA laddering protocol (17) with slight modifications. Cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 % NP-40, 20 mM EDTA), pelleted at 16,000 g (5 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was subjected to one round of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1; pH 7.4; 0.5 mL) extraction. Apoptotic DNA fragments were precipitated from the liquid phase by adding 50 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), 1 μL nuclease free glycogen (Roche) and 0.6 mL isopropanol. After incubation on ice for 5 min, precipitated nucleic acids were pelleted by centrifugation at 12,900g (10 min, 4°C). After washing with 70 % ethanol, the pellet was reconstituted in TE buffer and DNA concentrations were measured by spectrophotometry. Equal amounts of DNA were digested with RnaseOne (Promega). After digestion, 5X Orange G dye was added to each sample and the apoptotic DNA fragments were resolved by 1.8% TAE agarose gel electrophoresis.

Annexin Flow Cytometry

To assess apoptosis by the appearance of annexin V on the cell surface, cells were washed with PBS, harvested using 0.25% trypsin (Sigma) and centrifuged at 500g for 5 min. After repeated washing, cells were resuspended in annexin binding buffer and stained using the Vybrant Apoptosis Assay Kit #3 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cells were stained with 5 μl of annexin V conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Component A) and 1 μl of 100 μg/ml propidium iodide (Component B). Following incubation for 30 min in darkness at room temperature, the cells were immediately analyzed in a FACSort Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Annexin binding and propidium iodide internalization were quantified using FL1 and FL3 channels, respectively. A minimum of 10,000 events was collected for each condition. All experiments were reproduced at least in triplicate using three independent experiments.

Measurement of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species

Cellular ROS generation was assayed by using 2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (DCF, Invitrogen). Cells were washed with PBS, harvested using 0.25% trypsin, centrifuged at 500g for 5 min, and resuspended in PBS. Cells were incubated with 10 μM DCF for 10 min at room temperature. Because DCF is unstable in solution, a fresh 10 mM stock was prepared for each experiment. After staining, cells were treated with various agents and promptly analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSort Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson). A minimum of 50,000 events was collected for each condition and all experiments were reproduced at least in triplicate.

Tumor Cell Xenotransplantation

HCT116 cells stably expressing UCP2 (clone ZU7) and empty vector controls (clone ZE12) were subcutaneously injected into the lower flanks of NCr nu/nu mice (Taconic Farms) at a dose of 3 × 106 viable tumor cells. Mouse tumor growth was measured with digital caliper and calculated by using the formula of a rotational ellipsoid V = π/6 × A × B2, where V is volume, A is the longest and B is the perpendicular shorter tumor axis. In vivo chemotherapy with irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11, Pfizer) was started after 2 weeks once xenografts reached an average volume of at least 100 mm3. CPT-11 was administered at a dose of 25 mg/kg intraperitoneally every third day for 2 weeks. All animal experiments were performed in accordance to the institutional guidelines of Lifespan Animal Welfare Committee of Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor xenografts were removed and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C, then dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4 μm thickness. Tissue slides were stained with C-20 goat polyclonal anti-UCP2 antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz), followed by biotinylated secondary horse anti-goat antibody (1:500; Vector), and visualized using peroxidase (Vector).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with unpaired Student t test or ANOVA when multiple comparisons were made. Differences with calculated P values <0.05 were regarded as significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

UCP2 overexpression protects cancer cells from apoptosis and oxidative stress

To examine the functional importance of UCP2 in cancer cells, we have overexpressed the plasmid-encoded cDNA of human UCP2 in HCT116, a human colon cancer cell line with low endogenous UCP2 levels (Figure 1A and 1B). Recombinant UCP2 was synthesized at high levels and targeted successfully to the mitochondrial inner membrane of HCT116 cells (Figure 1C). Consistent with increased uncoupling (9), UCP2-overexpressing HCT116 cells displayed diminished baseline Δψm (Figure 1D, left) and increased oxygen consumption (Figure 1D, middle), while their intracellular ATP levels remained unchanged (Figure 1D, right). Since UCP2 has no apparent effect on net proton conductance unless activated by superoxide or ROS-derived alkenals (9), these findings affirm that baseline oxidant levels are sufficiently high to activate plasmid-encoded UCP2 in HCT116 cells.

Figure 1. Overexpression of UCP2 in cancer cells.

(A) Cell line selection for overexpression experiments. Endogenous UCP2 mRNA levels in various human colon cancer cell lines determined by quantitative real time PCR and expressed as relative ratios over the mRNA of TATA-box binding protein shown in arbitrary units ± SEM. (B) Immunoblot analysis of UCP2 in the mitochondrial fraction of HCT116 cells transfected with various amounts of hUCP2-pcDNA3.1/Zeo(−) plasmid containing the full-length human ucp2 cDNA (pUCP2) or with empty vector (EV) indicates dose-dependent expression of plasmid-encoded UCP2, while endogenous UCP2 protein in these cells is essentially non-detectable. Subunit IV of cytochrome c oxidase (COX IV) served as loading control. (C) Plasmid-encoded UCP2 is properly targeted to the mitochondrial inner membrane (IM). Mitochondria of HCT116 cells were isolated and sub-fractionated 48 hours after transfection with 2 μg of plasmid. Immunoblotting indicates the presence of plasmid-encoded UCP2 in IM fraction (identified by COX IV), but not in the inter-membrane space (identified by cytochrome c). OM, mitochondrial outer membrane. (D) Functional analysis of plasmid-encoded UCP2. Left, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) of HCT116 cells in response to UCP2 overexpression assessed by red to green JC-1 fluorescence ratios and shown in percentages (± SEM) relative to non-transfected cells (no DNA). Experimental controls to abolish or elevate Δψm included the chemical uncoupler FCCP (10 μM) and the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (10 μM), respectively. Middle, oxygen consumption (pmol min−1 cell−1 ± SEM) measured by polarography using a Clark-type oxygen-sensitive electrode. Right, intracellular ATP content (pmol 103 cells−1 ± SEM) measured by luciferin-luciferase assay. *P < 0.05 for differences between pUCP2 vs. EV.

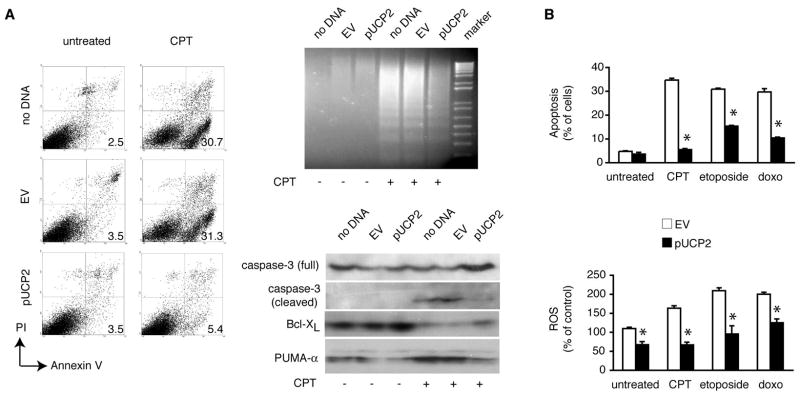

To determine whether UCP2 overexpression can block apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs, we treated HCT116 cells with camptothecin (CPT), a topoisomerase I inhibitor with derivatives widely used in the clinical management of colon cancer (18). Such agents cause DNA strand breaks and initiate a series of events that may contribute to increased oxidative stress, culminating in cell death (18). Apoptosis induced by CPT was markedly diminished in UCP2 overexpressing HCT116 cells as determined by annexin V flow cytometry (Figure 2A, left) and DNA ladder gel electrophoresis (Figure 2A, right top). Furthermore, UCP2 overexpression in HCT116 cells resulted in decreased cleavage and activation of the key apoptosis effector caspase-3, increased abundance of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL protein, and less expression of PUMA-α (Figure 2A, right bottom) an essential pro-apoptotic protein targeted by the tumor suppressor p53 (19, 20). These data further indicate that plasmid-encoded UCP2 confers resistance to HCT116 cells from CPT-induced. Apoptosis was similarly diminished in UCP2 overexpressing HCT116 cells treated with two topoisomerase II inhibitors, etoposide and doxorubicin, demonstrating that the protective effect of UCP2 is not limited to CPT and topoisomerase I blockade (Figure 2B, top). Moreover, UCP2 overexpression resulted in 30% decrease of apoptosis induced by exposure of HCT116 cells to UV radiation (40 J/m2 for 15 min), indicating the ability of UCP2 to rescue cancer cells from various types of cytotoxic injury (not shown).

Figure 2. UCP2 inhibits apoptosis and decreases ROS levels in cancer cells.

HCT116 human colon cancer cells without transfection (no DNA), transfected with 2 μg empty vector (EV), or 2 μg hUCP2-pcDNA3.1/Zeo(−) plasmid (pUCP2) were exposed to camptothecin (CPT, 2.5 μM), etoposide (10 μM), or doxorubicin (doxo, 20 μM) for 24 hours except as indicated. (A) Analysis of CPT-induced apoptosis. Left, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide (PI). Results are shown in dot plots with 4-decade log scale with percentages of apoptotic cells (lower right quadrant). Right top, DNA fragmentation was assessed by accelerated DNA ladder gel electrophoresis. Marker, DNA molecular weight control. Right bottom, immunoblot analysis of pro-apoptotic (full and cleaved caspase-3, PUMA-α) and anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-XL). (B) Impact of UCP2 overexpression on cellular responses to various cytotoxic drugs. Top, mean rates of apoptosis (± SEM) are expressed as the percentage of total cell number assessed by annexin V flow cytometry. Bottom, intracellular ROS levels assessed by DCF flow cytometry. DCF fluorescence is expressed as the percentage of levels measured in non-transfected, untreated cells (mean ± SEM) at baseline and following treatment for 30 min. *P < 0.05 for difference between pUCP2 vs. EV. All treatments were initiated 24 hours after transfection.

Chemical uncoupling simulates the effect of UCP2 overexpression in cancer cells

Pretreatment with low doses of the chemical uncoupler carbonylcyanide-4-trifluoro-methoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) also protected HCT116 cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors (Figure 3A). Since FCCP is a pure protonophore, these findings support the role of proton leak in the anti-apoptotic effect of UCP2. The protective effect of uncoupling was further demonstrated by lower intracellular ROS levels in HCT116 cells exposed to chemotherapeutic agents following either UCP2 overexpression (Figure 2B, bottom) or treatment with low-dose FCCP (Figure 3B). Importantly, HCT116 cells had increased rates of cell death including necrosis when exposed to FCCP at doses of 5 μM and above (Figure 3A, left). In addition, progressively lower cellular ATP levels were noted in cells exposed to higher doses of FCCP prior to any further treatment (Figure 3C), indicating that excessive chemical uncoupling causes marked energy compromise with loss of cytoprotection. In contrast, the effect of UCP2 overexpression on baseline cellular ATP levels in HCT116 cells was negligible at applied plasmid concentrations (Figure 1D, right). Altogether, the findings are in agreement with the concept of limited or ‘mild uncoupling’ as an important biological mechanism (8, 9) and link the regulated mitochondrial proton leak to the control of oxidative stress and apoptosis in cancer cells.

Figure 3. Uncoupling mimics the effect of UCP2 in cancer cells.

(A) At the doses indicated, HCT116 cells were treated with the protonophore carbonylcyanide-4-trifluoro-methoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) 30 min prior to the addition of CPT for 24 hours. Apoptosis was assessed by (left) annexin V staining, (right top) DNA ladder formation, (right middle) caspase-3 cleavage, and (right bottom) disappearance of Bcl-XL. For additional details, please see Figure 1. Note increased number of cells staining for both annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) in response to 5 μM FCCP (and at higher doses, not shown) in the right upper quadrants, indicating concomitant increase in necrotic cell death. Results are each from at least two independent experiments. (B) Intracellular ROS levels (mean ± SEM, expressed as the percentage of levels measured by DCF in untreated cells) at baseline and in response to treatment with 2.5 μM CPT for 30 min. ROS levels in cells treated with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 2.5 mM) are shown for comparison. (C) Intracellular ATP content (pmol 103 cells−1 ± SEM) measured by luciferin-luciferase assay shows dose-dependent decrease following treatment with FCCP, but FCCP has no further effect on markedly decreased ATP levels in cells exposed to 2.5 μg camptothecin (CPT) for 24 hours. *P < 0.05 for differences between cells with or without treatment with CPT; ‡ P < 0.05 for differences between cells with or without treatment with FCCP.

UCP2 promotes in vivo chemoresistance in cancer cells

Next, we analyzed in vivo effects of UCP2 on drug resistance of colon cancer cells. We generated subcutaneous xenografts in NCr nu/nu mice by using wild type p53 HCT116 cells that stably overexpress UCP2 (clone ZU7) compared to empty vector controls (clone ZE12) (Figure 4A). Triaxial measurements indicated no difference between spontaneous growth rates of xenografts containing cells overexpressing UCP2 and cells transfected with empty vector (Figure 4B). Tumor growth markedly regressed in response to treatment with the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11) in mice that received xenografts of ZE12 cells. In contrast, UCP2-overexpressing ZU7 cells were much more resistant to CPT-11. These in vivo observations provide further evidence that increased levels of UCP2 augment chemoresistance in colon cancer cells.

Figure 4. UCP2 promotes in vivo drug resistance in cancer cells.

(A) Detection of UCP2 expression by immunoblot analysis (top) and immunohistochemistry (bottom) in subcutaneous xenografts of HCT116 cells stably expressing UCP2 (ZU7, right panel) or empty vector controls (ZE12, left panel) inoculated at a dose of 3 × 106 cells into both flanks of 4-6 weeks old male NCr nu/nu mice (n = 8-8). ZE12 cells with scattered and faintly positive staining reflect endogenous UCP2 expression. β-actin served as loading control. Magnification, 400X. (B) Growth of HCT116 cancer cell xenografts monitored by triaxial measurements. Two weeks after inoculation of HCT116 cells, mice were treated with irinotecan (CPT-11) at a dose of 25 mg/kg i.p. every 3 days (arrows). Controls received saline injection. *P < 0.05 for difference between ZU7 vs. ZE12 following CPT-11 treatment.

P53-dependent protection of cancer cells from apoptosis by UCP2

To investigate the link between diminished intracellular ROS levels and cell death rates in UCP2-overexpressing HCT116 cells treated with cytotoxic agents, we next examined the role of the pivotal tumor suppressor p53 in this process. HCT116 cells possess wild type p53 that is a plausible target of UCP2 for several reasons. As shown above, UCP2 overexpression results in reduced expression of PUMA-α, an important pro-apoptotic effector of p53. Furthermore, as recently proposed, ROS provide a major stimulus to p53 stabilization and subsequent induction of apoptosis by a feed-forward regulatory loop (21). Consistent with this concept, decreases of mitochondrial ROS levels by chemical inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation abrogate p53-dependent apoptosis in human T-lymphocytes and MOLT-3 leukemia cells expressing wild type p53 (22). To determine if inhibition of apoptosis by increased mitochondrial uncoupling depends on the presence of p53, we overexpressed UCP2 in p53−/− HCT116 cells. Cell cycle analysis in p53−/− HCT116 cells transfected with empty vector and treated with CPT demonstrated lack of G1/S arrest and lower rates of cell death (P < 0.0001 vs. wild type), both consistent with augmented chemoresistance in the absence of functional p53 (Figure 5A). However, diminished susceptibility to CPT in p53−/− HCT116 cells was not further altered by UCP2 overexpression (P = NS vs. wild type), suggesting that cytoprotection by mitochondrial uncoupling is not additive with the absence of wild type p53 (Figure 5A). Notably, UCP2 overexpression did not alter CPT-induced activation of the G1/S checkpoint in p53+/+ HCT116 cells (Figure 5A), suggesting that plasmid-encoded UCP2 interferes with p53-mediated apoptosis, but has no effect on p53-mediated cell cycle arrest under these conditions.

Figure 5. UCP2 interferes with p53 responses in cancer cells.

(A) Cell cycle analysis of p53+/+ and p53−/− HCT116 cells with no transfection (no DNA), transfected with 2 μg empty vector (EV), or with 2 μg hUCP2-pcDNA3.1/Zeo (−) plasmid (pUCP2) and treated with CPT (2.5 μM) for 24 hours. Sub-G1 fraction is indicated as apoptosis. (B) Immunoblot analysis of post-translational modification and accumulation of p53 in HCT116 cells overexpressing UCP2 (pUCP2) treated with CPT (2.5 μM) for 24 hours. N-terminal phosphorylation of p53 at selected serine residues (Ser15, Ser33, Ser46) responsive to oxidative stress and abundance of total p53 is shown. β-actin served as loading control. (C) Glycolytic activity was assessed by measuring lactate levels in the medium of HCT116 cells stably expressing UCP2 (ZU7) or empty vector controls (ZE12) at various times after seeding into culture. (D) Suppression of cell growth by inhibiting glycolysis in HCT116 cells plated 24h prior to the addition of 50 mM 2-deoxyglucose. Numbers of viable cells are expressed in percentage of pretreatment counts. *P < 0.01; ‡P < 0.0001 for differences between ZU7 vs. ZE12.

UCP2 interferes with post-translational modification of p53 in cancer cells

A well recognized mechanism of p53 activation involves phosphorylation of its N-terminal domain in response to upstream stress signals (23). Rapid phosphorylation of Ser15 is considered a ‘priming event’ in response to genotoxic stresses (24). This is followed by modifications that involve a number of N-terminal p53 residues directly or indirectly responsive to oxidative stress, including Ser33 and Ser46 by the stress-activated protein kinase p38 (25, 26), Ser20 and Ser46 by protein kinase C δ (27, 28), and Thr81 by c-jun N-terminal kinase (29). To explore links between diminished ROS levels and p53-mediated apoptosis in HCT116 cells, we tested the effect of plasmid-encoded UCP2 on N-terminal p53 phosphorylation. We noted that phosphorylation of p53 induced by 2.5 μM CPT in UCP2 overexpressing HCT116 cells was markedly diminished at the designated Ser15, Ser33, and Ser46 residues (Figure 5B). Of note, total p53 abundance remained essentially unchanged, indicating no apparent effect of UCP2 overexpression on p53 accumulation in response to CPT. These data suggest that UCP2 inhibits apoptosis of HCT116 cells by interfering with the ROS-mediated phosphorylation of p53 within the transactivation domain. Further studies will be necessary to identify UCP2-specific patterns for post-translational modification of p53 and the signaling mediators and other molecular partners involved in this process.

UCP2 overexpression promotes the glycolytic phenotype in cancer cells

P53 appears to be involved in the regulation of energy metabolism, potentially via interactions with UCP2. As recently reported, p53 stimulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption by inducing the expression of SCO2, a subunit of the cytochrome c oxidase complex that is embedded in the respiratory chain, revealing a further novel mechanism for tumor suppression (30). Furthermore, the product of another p53-inducible gene, TIGAR (TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator) lowers the intracellular levels of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, a key substrate in glycolysis (31). Thus, p53 may compromise the Warburg effect, a metabolic hallmark of many cancer cells (32), by increasing oxidative phosphorylation, inhibiting glycolysis, and preserving the balance between these two differing ATP-generating pathways. Indeed, there is decreased oxygen consumption and increased lactate production in p53-deficient cells (30). In line with these observations, we found that HCT116 cells that stably overexpress UCP2 produce progressively more lactate than empty vector transfected control cells in culture (Figure 5C). Moreover, treatment of UCP2-overexpressing HCT116 cells with the glucose analog 2-deoxyglucose, a potent inhibitor of glycolysis, results in suppression of cell growth, consistent with increasing dependence on glycolytic ATP production (Figure 5D).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that UCP2 modulates the cellular adaptive response of cancer cells. Increased expression of UCP2 may provide a marker of chemoresistance in p53-mutant cell lines (Figure 1A) and in the setting of neoplasia (11) of the human colon. We also show that UCP2 appears to have an active role in promoting cancer cell survival that is linked to mitochondrial suppression of ROS production. Moreover, anti-apoptotic effects of UCP2 via ROS involve modulation of the p53 pathway, a pivotal tumor suppression mechanism. Finally, this interaction also affects the balance of cellular energy production since UCP2 overexpression preferentially induces the glycolytic phenotype in cancer cells. Altogether, the data identify UCP2 as a potential molecular target of novel treatment strategies in cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, under grants DK-61890 and RR-17695 to G.B. We thank Sara Spangenberger at Core Research Laboratories and Tamako A. Garcia at the Liver Research Center, Rhode Island Hospital, for their respective help with flow cytometry assays and immunohistochemistry studies. The authors of this article declare no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:276–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schumacker PT. Reactive oxygen species in cancer cells: live by the sword, die by the sword. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:175–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? Biochem J. 2007;401:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552:335–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ. Bioenergetics: An introduction to the chemiosmotic theory. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starkov AA. “Mild” uncoupling of mitochondria. Biosci Rep. 1997;17:273–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1027380527769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand MD, Esteves TC. Physiological functions of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3. Cell Metab. 2005;2:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattiasson G, Sullivan PG. The emerging functions of UCP2 in health, disease, and therapeutics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1–38. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horimoto M, Resnick MB, Konkin TA, et al. Expression of uncoupling protein-2 in human colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6203–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper ME, Antoniou A, Villalobos-Menuey E, et al. Characterization of a novel metabolic strategy used by drug-resistant tumor cells. Faseb J. 2002;16:1550–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0541com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins P, Jones C, Choudhury S, Damelin L, Hodgson H. Increased expression of uncoupling protein 2 in HepG2 cells attenuates oxidative damage and apoptosis. Liver Int. 2005;25:880–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roig J, Traugh JA. p21-activated protein kinase gamma-PAK is activated by ionizing radiation and other DNA-damaging agents. Similarities and differences to alpha-PAK. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31119–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pecqueur C, Alves-Guerra MC, Gelly C, et al. Uncoupling protein 2, in vivo distribution, induction upon oxidative stress, and evidence for translational regulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8705–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi T, Wang F, Stieren E, Tong Q. SIRT3, a mitochondrial Sirtuin deacetylase, regulates mitochondrial function and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13560–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeung MC. Accelerated apoptotic DNA laddering protocol. Biotechniques. 2002;33:734, 6. doi: 10.2144/02334bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willson JK. Topoisomerase-I inhibitors in the management of colon cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;803:256–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb26395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7:683–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffers JR, Parganas E, Lee Y, et al. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:321–8. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang PM, Bunz F, Yu J, et al. Ferredoxin reductase affects p53-dependent, 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1111–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karawajew L, Rhein P, Czerwony G, Ludwig WD. Stress-induced activation of the p53 tumor suppressor in leukemia cells and normal lymphocytes requires mitochondrial activity and reactive oxygen species. Blood. 2005;105:4767–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavin MF, Gueven N. The complexity of p53 stabilization and activation. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:941–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appella E, Anderson CW. Post-translational modifications and activation of p53 by genotoxic stresses. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2764–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulavin DV, Saito S, Hollander MC, et al. Phosphorylation of human p53 by p38 kinase coordinates N-terminal phosphorylation and apoptosis in response to UV radiation. Embo J. 1999;18:6845–54. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Prieto R, Rojas JM, Taya Y, Gutkind JS. A role for the p38 mitogen-acitvated protein kinase pathway in the transcriptional activation of p53 on genotoxic stress by chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2464–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi T, Miki Y, Yoshida K. Protein kinase C delta activates IkappaB-kinase alpha to induce the p53 tumor suppressor in response to oxidative stress. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2088–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emoto Y, Kisaki H, Manome Y, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Activation of protein kinase Cdelta in human myeloid leukemia cells treated with 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine. Blood. 1996;87:1990–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buschmann T, Potapova O, Bar-Shira A, et al. Jun NH2-terminal kinase phosphorylation of p53 on Thr-81 is important for p53 stabilization and transcriptional activities in response to stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2743–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2743-2754.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matoba S, Kang JG, Patino WD, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warburg O. The metabolism of tumours. London: Arnold Constable; 1930. pp. 254–70. [Google Scholar]