Abstract

Objective

Distal third tibia fractures have classically been treated with standard plating, but intramedullary (IM) nailing has gained popularity. Owing to the lack of interference fit of the nail in the metaphyseal bone of the distal tibia, it may be beneficial to add rigid plating of the fibula to augment the overall stability of fracture fixation in this area. This study sought to assess the biomechanical effect of adding a fibular plate to standard IM nailing in the treatment of distal third tibia and fibula fractures.

Methods

Eight cadaveric tibia specimens were used. Tibial fixation consisted of a solid titanium nail locked with 3 screws distally and 2 proximally, and fibular fixation consisted of a 3.5 mm low-contact dynamic compression plate. A section of tibia and fibula was removed. Testing was accomplished with an MTS machine. Each leg was tested 3 times; with and without a fibular plate and with a repetition of the initial test condition. Vertical displacements were tested with an axial load up to 500 N, and angular rotation was tested with torques up to 5 N•m.

Results

The difference in axial rotation was the only statistically significant finding (p = 0.003), with fibular fixation resulting in 1.1° less rotation through the osteotomy site (17.96° v. 19.10°). Over 35% of this rotational displacement occurred at the nail–locking bolt interface with the application of small torsional forces.

Conclusion

Fibular plating in addition to tibial IM fixation of distal third tibia and fibula fractures leads to slightly increased resistance to torsional forces. This small improvement may not be clinically relevant.

Abstract

Objectif

On traite habituellement les fractures du tiers distal du tibia en posant une plaque standard, mais le clou centromédullaire (CM) gagne en popularité. Comme rien ne nuit à l'ajustement du clou dans la métaphyse de la partie distale du tibia, il peut être avantageux d'ajouter une plaque rigide au péroné afin de stabiliser davantage la fixation de la fracture dans cette région. Au cours de cette étude, nous avons cherché à évaluer l'effet biomécanique de l'ajout d'une plaque fibulaire au clou CM standard dans le traitement de fractures du tiers distal du tibia et du péroné.

Méthodes

On a utilisé 8 spécimens de tibia de cadavre. On a fixé le tibia avec un clou en titane plein maintenu en place au moyen de 3 vis à la partie distale et de 2 vis à la partie proximale, et la fixation fibulaire a consisté en une plaque de compression dynamique à faible contact de 3,5 mm. On a enlevé une section du tibia et du péroné. On a réalisé le test au moyen d'une machine MTS. Chaque jambe a été soumise au test trois fois : avec et sans plaque fibulaire et avec répétition de la condition initiale. On a testé les déplacements verticaux au moyen d'une charge axiale atteignant 500 N et la rotation angulaire au moyen de couples atteignant 5 N•m.

Résultats

La différence au niveau de la rotation axiale a constitué la seule constatation statistiquement significative (p = 0,003), et la fixation fibulaire a produit une rotation de 1,1° de moins au site de l'ostéotomie (17,96° c. 19,10°). Plus de 35 % de ce déplacement par rotation s'est produit à l'interface clou-blocage avec l'application de faibles forces de torsion.

Conclusion

La pose d'une plaque fibulaire qui s'ajoute à la fixation CM du tibia dans le cas de fractures du tiers distal du tibia et du péroné augmente légèrement la résistance aux forces de torsion. Il est possible que cette faible amélioration ne soit pas pertinente sur le plan clinique.

Combined fracture of the tibia and fibula is a common orthopedic injury that can be treated nonoperatively in a cast or surgically by using external fixators, plates or intramedullary (IM) nails. Biomechanical studies and clinical research have shown that instrumentation of midshaft tibial fractures with an IM nail results in a stable fixation with high union rates, low infection rates and minimal soft tissue stripping; it has therefore become a preferred method of fixation.1 There is clinical evidence that distal third tibia fractures can also be successfully treated with IM fixation.2–4 It has been shown that fibular fixation in addition to IM tibial nailing is unnecessary when a midshaft tibial fracture is accompanied by an ipsilateral fibular shaft fracture.5 For a combined distal tibia and fibula fracture, there exists a debate among surgeons as to whether or not fibular fixation is required as an adjuvant to IM nailing. Some authors have demonstrated that spiral fractures of the distal tibia treated with IM nailing have a tendency toward malalignment,6,7 and some biomechanical data support this notion.8 Conversely, a retrospective study of 157 combined open tibia and fibula fractures showed that, regardless of the fracture level, fibular fixation did not offer any advantage when compared with standard IM nailing.9

Presently, there is no clear consensus on the optimum management of combined distal third tibia and fibula fractures.

Our objective was to determine whether combined distal third tibia and fibula fractures are more stable when fibular fixation is added to the standard tibial IM nailing in a cadaveric model with segmental instability of the tibia and fibula.

Methods

Specimen selection and instrumentation

Paired embalmed cadaveric lower legs where disarticulated at the knee. All soft tissue was removed from the leg, except for the interosseous membrane and the soft tissue about the ankle, which were left intact. We used 4 specimens to establish specimen preparation and the testing protocol, and we entered 4 paired specimens into the study using the final study protocol. None of the legs possessed any obvious deformities or bone pathology on close inspection.

After block randomization, 1 leg from each pair of lower limbs initially received a tibial nail and a fibular plate, whereas the other leg initially received only a tibial nail. We reamed all tibias to 10 mm with flexible IM reamers (Synthes, Westchester, Pa.) and then rodded with a 9-mm titanium nail (Synthes), using accepted operative techniques. The lengths of the nails were as follows: 285, 285, 315, 315, 330, 330, 330 and 330 mm. Fluoroscopy was used throughout the procedure. We placed 2 proximal locking bolts (medial to lateral) and 3 distal locking bolts (2 medial to lateral and 1 anterior to posterior) under fluoroscopic guidance.

After tibial nail insertion, osteotomies of the fibula and tibia were created 6.5 cm above the tibial plafond. We removed 1 cm of fibula and 1.5 cm of tibia proximal to the osteotomy line.10

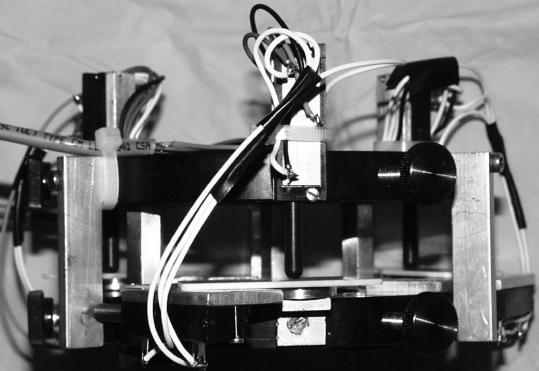

Fibular fixation was accomplished with the use of a 7-hole, 3.5-mm, low-contact dynamic compression plate plate (Synthes) centred on the osteotomy site; 3 proximal and 3 distal cortical screws were used (Fig. 1). The surgeries were performed by the principal author (P.M.) and by a trained trauma surgeon (R.R.).

FIG. 1. Picture of a pair of specimens, one with a tibial nail alone and the other with a nail and fibular plate.

Specimen preparation

The proximal tibia was embedded in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) (DenPlus, Montréal, Que.), and four 2-mm diameter K-wires were placed across the tibial plateau to improve anchorage of the PMMA pots located around the proximal tibia. We ensured that the fibular head and the entry point of the tibial nail were clear of cement so that the proximal tibia-fibula joint could move freely and so that no forces would be transferred directly through the PMMA to the tibial nail. The foot was fixed in a plantegrade position to a piece of wood measuring 2 × 6 × 12 inches; screws were placed through the talus, calcaneus and first and fifth metatarsal heads (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2. Specimen with schematic drawing illustrating the osteotomy at the distal tibia and fibula. The intramedullary nail is locked proximally and distally. The potentiometers are attached to plastic resin rings fixed to the tibia proximal and distal to the osteotomy site.

Mechanical testing

We used an MTS machine for biomechanical testing (model 858.01 Mini-Bionix, MTS Systems Corp., Eden Prairie, Minn.). Movement across the osteotomy site was recorded in 3 dimensions: the z axis runs from caudad to cephalad, the x axis runs from anterior to posterior, and the y axis runs from medial to lateral. (Fig. 3) The wood block was bolted to the base of the MTS machine, which allows translation in the x and y axis. The upper platform of the MTS was lowered and locked onto the proximal PMMA block. We used a plumb line to align the z axis of the tibia vertically in the coronal and sagittal planes, using the tibial spine proximally and the centre of the ankle joint distally as a reference. When axial compression (FZ) was applied, the lower platform of the MTS machine was locked and the upper platform was free to swivel or rotate in all directions. When rotation (MZ) was applied, the upper platform was locked and the base plate was free to translate in the x–y plane. Between testing both ends of the specimen were loosened and the tibia was realigned.

FIG. 3. Axes used for loads and moments.

Axial loading to 500 N was applied at a rate of 50 N/s. This load approximates the load during partial weight bearing.5,11

We tested rotation about the z axis by applying internal and then external torque at the rate of 0.25 N•m/s up to a maximum load of 5 N•m. The leg was preloaded with a 50-N axial force throughout rotational testing.12,13

All displacements and rotations across the osteotomy site were recorded with a custom-made goniometer (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) interfaced to the analog IO connections at the MTS controller. This device consisted of 2 Delrin acetal resin rings, (DuPont Canada, Mississauga, Ont.) mounted in parallel with a 3-point “Christmas tree” fastening arrangement of pointed machine screws. The rings were kept parallel and at a fixed initial distance. Three potentiometers spaced at 120° around the rings measured vertical displacement across the osteotomy site. Combined measurements of the potentiometers allowed trigonometric calculation of varus or valgus (Rot X), pro-or recurvatum (Rot Y) and vertical displacement (Trans Z) during axial loading. Similarly, for rotational testing (Rot Z), 3 potentiometers spaced at 120° around the rings. Values from the potentiometers were averaged.

FIG. 4. Custom-made goniometer.

FIG. 5. Custom-made goniometer.

The goniometer was calibrated before and after all testing by using the internal linear variable displacement transducer of the MTS machine as a reference. The MTS factory sensors have a combined accuracy and linearity of less than 0.3% of full-scale, with full-scale being 270° for the angular displacement transducer. The combined axial compression/tension and torsion load cells (N or N•m) have a combined accuracy and linearity 0.08% of full-scale with full-scale being 2000 N and 100 N•m. Hysteresis is 0.05%. Worst-case combined errors were 1.73% root mean square (RMS) for axial rotation, and 0.70% RMS for vertical displacement.

To prevent introduction of a bias, we first tested one-half of the specimens with the plate and the other one-half without the plate. Each leg was tested under 3 instrumentation conditions. The first testing condition depended on the group the specimen was randomized to, and the second test condition consisted of the alternative construct. For example, if the specimen was randomized to the IM nail group, the first test condition was the IM nail alone, whereas the second test condition was the IM nail and the fibular plate together. The third testing condition was a repeat of the original test condition, which in this case would be the IM tibial nail alone. Each specimen was tested 4 times. The first 3 runs were used for preconditioning and the fourth was used for data collection.

The exact testing sequence was as follows:

• The specimen was mounted onto the MTS machine and aligned with a plumb line.

• Three preconditioning runs of axial loading to 500 N were applied, followed by a fourth run for data collection.

• The ends of the specimen were loosened and the tibia was realigned.

• A preload of 50 N was applied to the specimen, and then it was subjected to 3 preconditioning runs of torque to +5 N•m and –5 N•m, followed by a fourth run that was used for data collection.

• Next, the fibular fixation was changed to the alternative type of fixation, and the specimen was again realigned.

• Steps 2 through 4 were repeated for the second test condition.

• Finally, the fibular fixation was changed back to the original test condition and steps 2 through 4 were repeated for the last time for that specimen.

The data collected for rotation about the z axis were expressed as degrees and were divided into 2 sets of data for each testing condition. They were range of motion (ROM), which represents a full cycle of internal and external rotation, and neutral zone (NZ), which represents the total amount of rotation in a full cycle that occurs when zero torque is measured through the construct. The NZ represents the looseness of the nail–locking bolt interface. The data collected for maximum vertical displacement about the z axis and maximum rotation around the x and y axes were expressed as millimetres and degrees of displacement, respectively.

We used a paired t test to compare the mean difference in displacement, rotation and angulation for the different instrumentation conditions. Because we measured multiple outcomes that were not independent, we applied a Bonferroni correction; therefore, we used a p value of 0.01 instead of 0.05 for the statistical analysis.

Results

Axial rotation values for the study and control groups at ± 5 N•m of torque demonstrate a statistically significant decrease of 1.1º with the fibular plate applied. The mean ROM was measured as 18.0º and 19.1º with and without the fibular plate, respectively. A significant proportion of this motion occurred through the NZ when no torque was applied (Table 1). With respect to angular and vertical displacement, the numbers were small. No statistically significant difference was registered between the specimens with and without the fibular plate (Table 1).

The third testing condition, which repeated the first for each specimen, showed that the testing protocol did not alter the mechanics, because we found no significant difference in the measurements between the first and the third testing conditions in any of the specimens. This allowed us to essentially use each tibia as its own control.

Discussion

The management of tibia fractures has evolved significantly over the past decade. IM nailing has become the standard of care for most of these injuries, especially in cases with significant soft tissue compromise. The lack of interference fit of IM nails in the tibial metaphysis has prompted some surgeons to add fibular plating in the hopes of improving fracture stability. This biomechanical study is at odds with a recent retrospective study by Egol and colleagues4 that suggests a higher failure rate in patients whose fibulas were not plated. These patients present a range of fixation configurations ranging from 1 to 3 distal locking screws. The proximal fixation in these cases is not mentioned. The authors note that the number of distal locking bolts had an effect on the rate of malalignment. Although triple locking distally has become the standard at our institution for this fracture type, other centres commonly use 1 or 2 distal locking screws. It is possible that fibular plating becomes more important when fewer points of fixation are used in the tibia. In a similar biomechanical evaluation of distal tibia fractures, Kumar and colleagues14 found some beneficial effect of plating the fibula when a nail is used to stabilize the tibia. However, this beneficial effect is lost when torque greater than 1.68 N•m is used. Kumar and colleagues' results are therefore consistent with the ones presented in this study. We found that the IM nail offers excellent resistance to axial compression with very little movement and angulation across the osteotomy sites even at high loads (500 N). In rotation, however, the construct exhibits laxity, with up to 25° of movement at 5 N•m of torque. More than one-third of this movement occurred without any appreciable torque being applied and represented movement at the nail–locking bolt interface. This loose fit of the locking bolt within the nail facilitates locking of the nail with fluoroscopic guidance and is specific to the implant tested. Other nails may perform differently under these testing conditions. Interestingly, we also observed less movement in the specimens where the 3 distal locking bolts were not inserted perfectly in line with the corresponding holes in the nail. The only statistically significant difference between plating and not plating the fibula was found in axial rotation, where an improvement of 1.1º was found in the plated group. This small difference is not likely to be clinically relevant.

Although embalmed cadaveric tibias have been successfully used for lower-limb studies by other authors,15–17 freshly frozen specimens would be preferred. Additionally, we did not perform any bone density measurements. The tibias were harvested from elderly and potentially osteoporotic individuals. These factors introduce a bias toward the worst-case scenario with weak, osteoporotic bone.

Conclusions

This model assumes the use of the Synthes nail in ostoporotic bone where it is possible to place 3 distal and 2 proximal locking bolts. Under these conditions, fibular plating in addition to IM nailing of the tibia for distal third tibia fractures offers a small biomechanical advantage in rotation (1.1º at 5 N•m, p = 0.003). Vertical displacement and angulation are not statistically different between the 2 groups.

Contributors: Drs. Morin, Reindl, Harvey and Steffen designed the study. Drs. Morin, Reindl, Harvey and Beckman acquired the data, which all authors analyzed. Drs. Morin, Reindl and Harvey wrote the article, and all authors revised it. All authors gave final approval for the article to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Accepted for publication June 13, 2006

Correspondence to: Dr. Rudolf Reindl, McGill University Health Centre, Rm. B5 159.2, 1650 Cedar Ave., Montréal QC H3G1A4; fax 514 934-8394; rudy.reindl@muhc.mcgill.ca

References

- 1.Schnettler R, Borner M, Soldner E. [Results of interlocking nailing of distal tibial fractures]. [Article in German] Unfallchirurg 1990;93:534-7. [PubMed]

- 2.Mosheiff R, Safran O, Segal D, et al. The unreamed tibial nail in the treatment of distal metaphyseal fractures. Injury 1999; 30: 83-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Tyllianakis M, Megas P, Giannikas D, et al. Interlocking intramedullary nailing in distal tibial fractures. Orthopedics 2000; 23: 805-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Egol KA, Weisz R, Hiebert R, et al. Does fibular plating improve alignment after intramedullary nailing of distal metaphyseal tibia fractures? J Orthop Trauma 2006; 20:94-103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Weber TG, Harrington RM, Henley MB, et al. The role of fibular fixation in combined fractures of the tibia and fibula: a biomechanical investigation. J Orthop Trauma 1997;11:206-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Richter D, Hahn MP, Laun RA, et al. [Ankle para-articular tibial fracture. Is osteosynthesis with the unreamed intramedullary nail adequate?]. [Article in German] Chirurg 1998;69:563-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Strecker W, Suger G, Kinzl L. [Local complications of intramedullary nailing]. [Article in German] Orthopade 1996;25:274-91. [PubMed]

- 8.Duda GN, Mandruzzato F, Heller M, et al. Mechanical boundary conditions of fracture healing: borderline indications in the treatment of unreamed tibial nailing. J Biomech 2001;34:639-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Whorton AM, Henley MB. The role of fixation of the fibula in open fractures of the tibial shaft with fractures of the ipsilateral fibula: indications and outcomes. Orthopedics 1998;21:1101-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Morrison KM, Ebraheim NA, Southworth SR, et al. Plating of the fibula. Its potential value as an adjunct to external fixation of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991; 266: 209-13. [PubMed]

- 11.Duda GN, Mandruzzato F, Heller M, et al. Mechanical conditions in the internal stabilization of proximal tibial defects. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17: 64-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Schandelmaier P, Krettek C, Tscherne H. [Biomechanical studies of 9 tibial interlocking nails in a bone-implant unit]. [Article in German] Unfallchirurg 1994; 97:600-8. [PubMed]

- 13.Thomas KA, Bearden CM, Gallagher DJ, et al. Biomechanical analysis of nonreamed tibial intramedullary nailing after simulated transverse fracture and fibulectomy. Orthopedics 1997;20:51-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kumar A, Charlebois SJ, Cain EL, et al. Effect of fibular plate fixation on rotational stability of simulated distal tibial fractures treated with intramedullary nailing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85: 604-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.McBryde A, Chiasson B, Wilhelm A, et al. Syndesmotic screw placement: a biomechanical analysis. Foot Ankle Int 1997;18: 262-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Miller RS, Weinhold PS, Dahners LE. Comparison of tricortical screw fixation versus a modified suture construct for fixation of ankle syndesmosis injury: a biomechanical study. J Orthop Trauma 1999;13: 39-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Toolan BC, Koval KJ, Kummer FJ, et al. Vertical shear fractures of the medial malleolus: a biomechanical study of five internal fixation techniques. Foot Ankle Int 1994;15:483-9. [DOI] [PubMed]