Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the clinical consequences of psychological morbidity associated with orthopedic trauma. The objective of our study was to investigate the extent of psychological symptoms that patients experience following orthopedic trauma and whether these are associated with quality of life.

Methods

All patients attending 10 orthopedic fracture clinics at 3 university-affiliated hospitals between January and October 2003 were screened for study eligibility. Eligible patients were aged 16 years or older, were English-speaking, were being followed actively for a fracture(s), were cognitively able to complete the questionnaires and provided informed consent. All consenting patients completed a baseline assessment form, the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised and a health-related quality of life questionnaire (the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form [SF-36]). We conducted regression analyses to determine predictors of quality of life among study patients.

Results

Of the patients, 250 were eligible, and 215 agreed to participate; 59% were men; the patients' mean age was 44.5 (standard deviation [SD] 18.8) years. Over one-half (54%) of the patients had lower extremity fractures. Patient Physical Component summary scores were associated with older age (β = –0.28, p < 0.001), ongoing litigation (β = –0.18, p = 0.02), fracture location (β = –0.18, p = 0.01) and Positive Symptom Distress Index (i.e., the intensity of psychological symptoms; β = –0.08, p = 0.003). This model predicted 21% of the variance in patients' Physical Component summary scores. Somatization was an important psychological symptom negatively associated with Physical Component summary scores. Reduced Mental Component summary scores were associated with ongoing litigation (β = –0.18, p = 0.03) and Global Severity Index of psychological symptoms (β = –0.50, p < 0.001). This model explained 31% of the variability in patients' Mental Component summary scores.

Conclusion

In a prospective study of 215 patients, 1 in 5 met the threshold for psychological distress. Only ongoing litigation and psychological symptoms were significantly associated with both SF-36 Physical Component and Mental Component summary scores. Future research is necessary to determine whether orthopedic trauma patients would benefit from early screening and intervention to address comorbid psychopathology.

Abstract

Objectif

On connaît mal les conséquences cliniques de la morbidité psychologique associée au traumatisme orthopédique. Nous voulions déterminer l'étendue des symptômes psychologiques que les patients vivent à la suite d'un traumatisme orthopédique et établir le lien entre ces symptômes et la qualité de vie.

Méthodes

On a déterminé l'admissibilité à l'étude de tous les patients qui se sont présentés à 10 cliniques de traitement de fractures orthopédiques de 3 hôpitaux universitaires entre janvier et octobre 2003. Les patients admissibles avaient 16 ans ou plus, étaient anglophones, étaient suivis activement pour une fracture ou plus, avaient la capacité cognitive voulue pour remplir les questionnaires et ont donné leur consentement éclairé. Tous les patients consentants ont rempli un formulaire d'évaluation de référence, la liste de contrôle des symptômes 90 révisée (Symptom Checklist-90-Revised) et un questionnaire sur la qualité de vie liée à la santé (le questionnaire abrégé de 36 questions de l'étude sur les résultats médicaux — Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form [SF-36]). Nous avons procédé à des analyses de régression pour déterminer les prédicteurs de la qualité de vie chez les participants.

Résultats

Parmi les patients, 250 étaient admissibles et 215 ont consenti à participer; il y avait 59 % d'hommes et les patients avaient en moyenne 44,5 (écart-type [ET] 18,8) ans. Plus de la moitié (54 %) des patients avaient une fracture des membres inférieurs. On a établi un lien entre les scores sommaires de la fonction physique du patient et l'âge plus avancé (β = –0,28, p < 0,001), un litige en cours (β = –0,18, p = 0,02), le site de la fracture (β = –0,18, p = 0,01) et l'indice de détresse à symptômes positifs (c.-à-d. l'intensité des symptômes psychologiques; β = –0,08, p = 0,003). Ce modèle a prédit 21 % de la variation des scores sommaires de fonction physique des patients. La somatisation a constitué un symptôme psychologique important associé négativement aux scores sommaires de fonction physique. La baisse des scores sommaires de santé mentale était associée à un litige en cours (β = –0,18, p = 0,03) et à l'indice de gravité globale des symptômes psychologiques (β = –0,50, p < 0,001). Ce modèle a expliqué 31 % de la variabilité des scores sommaires de santé mentale des patients.

Conclusion

Au cours d'une étude prospective portant sur 215 patients, l'état d'un patient sur cinq correspondait au seuil de détresse psychologique. Des symptômes psychologiques ont associés significativement seulement à un litige en cours, à la fois selon les scores sommaires de fonction physique SF-36 et les scores de santé mentale. D'autres recherches s'imposent pour savoir si les patients victimes d'un traumatisme orthopédique bénéficieraient d'un dépistage et d'interventions précoces portant sur la psychopathologie comorbide.

Although trauma remains the leading cause of mortality in the first 4 decades of life, most people with traumatic injuries will survive their accident.1 Management of such patients focuses on patient medical resuscitation, stabilization of injuries and restoration of function.2 Costs related to trauma care in the United States have been estimated to exceed US$400 billion annually.3 Research is needed to identify factors associated with patient outcomes.

Several studies of patients with orthopedic trauma have focused on measures of functional recovery, complications, mortality and costs.4–7 Less attention has been focused on patient psychological status following orthopedic trauma — a common source of patient complaints and a clinically relevant outcome.8 The prevalence of psychological illness following traumatic injuries varies according to the diagnostic criteria used in studies, the timing of the assessment and definitions of trauma. Estimates of psychological symptoms following musculoskeletal trauma have ranged from 6.5% to 51.0%.8–14

Despite mounting evidence that non-injury–related factors have an important role in recovery from trauma, specific variables associated with clinical outcomes are poorly understood.15–17 This lack of knowledge complicates efforts to improve the care of orthopedic trauma patients. We report the findings of an observational study of patients attending 10 orthopedic fracture clinics that was designed to investigate the prevalence of psychological symptoms and their association with health-related quality of life.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an observational cross-sectional study to examine the prevalence of psychological symptoms among orthopedic trauma patients and the association of psychopathology with health-related quality of life. This study received ethics clearance through our local institutional review board.

Patient eligibility criteria

All patients attending 10 orthopedic fracture clinics at 3 university-affiliated hospitals between January 2003 and October 2003 were screened for study eligibility. Eligible patients were aged 16 years or older, were English-speaking, were being actively followed for a fracture(s), were cognitively able to complete the questionnaires and provided informed consent.

Patient assessment

During each clinic, a research assistant screened all patients for eligibility. On enrolment, a research assistant helped consenting patients to complete a baseline assessment form, a 90-item psychological symptom checklist (the Symptom Checklist- 90-Revised [SCL-90-R]) and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) health-related quality of life questionnaire. The initial assessment included the following demographic information: age, sex, level of education, social habits (i.e., smoking, alcohol use). Details on fracture location, on whether or not there was multitrauma or open fractures, on complications of fracture management and on time from injury were acquired from the attending surgeon at the same time as the patient assessment form was completed.

The attending surgeon (or representative such as a fellow or resident) reviewed each patient's relevant radiographs and clinical examination findings and provided the following information: overall satisfaction with the patient's current outcome (i.e., successful rather than unsuccessful) and overall perception about the quality of the fracture reduction. No specific criteria were provided to assess reduction status for each possible fracture type; however, physicians were instructed to decide on the basis of restored fracture anatomy (length, rotation and alignment) and stability of fracture fixation.

Assessment of psychological distress symptoms

We used the SCL-90-R to assess the current psychological symptom patterns of study participants.18 The SCL-90-R is a measure of current psychological symptom status; it has 9 symptom scales (Somatization, Obsessive–Compulsive, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation and Psychoticism) and 3 global indices (Global Severity Index, Positive Symptom Distress Index and Positive Symptom Total). The SCL-90-R requires a sixth-grade reading level and uses a 5-point Likert-type scale for all questions. This index can be administered in 15 minutes.

The SCL-90-R has been found both reliable and valid in orthopedic trauma populations; internal consistency (α coefficients range from 0.77 to 0.90) and test–retest reliability (range in r = 0.68–0.83) have been established.18–20 The SCL-90-R has been validated against the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, the Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Social Adjustment Scale and the General Health Questionnaire.18 The instrument has been evaluated in psychiatric patients and in patients with most major medical conditions.18 It has also been used in surgical studies evaluating patients with breast cancer and patients with fractures of the distal radius.10,21 Our decision to use the SCL-90-R was based on its ease of application and on the considerable data supporting its reliability and validity.18–20

Assessment of health-related quality of life

The SF-36 was developed from the Medical Outcomes Study.22 It is a self-administered, 36-item questionnaire that measures health-related quality of life in 8 domains (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, role limitations due to emotional problems, vitality, freedom from bodily pain, social functioning, mental health and general health perceptions). Each domain is scored separately from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest). Two summary scores (Physical Component and Mental Component) can be calculated from information in the 8 domains. The summary scores are based on a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10. Our decision to use the SF-36 over other available instruments was based on its widespread use in orthopedics, its use in previous studies evaluating fracture outcomes and strong evidence of its reliability and validity.23–27

Accuracy of data collection and data management

All data were analyzed with the SPSS Advanced Statistics software package (Version 10.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.). A second investigator reviewed all data entry to ensure accuracy and completeness.

Data analysis

We summarized baseline variables (age, sex, level of education, smoking status, alcohol use, details on fracture location, multitrauma or not, open fractures or not, complications of fracture management and time from injury) as means with SDs or proportions. Psychological symptoms (SCL-90-R) were presented as transformed scores (0–100 max), also known as T scores, which have the same percentile equivalents across scales. We converted T scores to percentiles of the normative population (matched for age and sex) by using published tables.18 We used previously published criteria of T scores of ≥ 63 to define those patients meeting the criteria for a psychological disorder.18 This definition, originally developed in large comparisons of psychiatric patients, has been found to be highly specific (specificity = 0.90).28,29 Mean scores for all 8 SF-36 domains were calculated and compared with published US norms. The Physical Component and Mental Component summary scores were presented as means with SDs.

We conducted univariate regression analyses to determine associations between independent variables (patient age, disability claim, ongoing litigation, level of education, fracture location, time since injury, technical outcomes, smoking, open fracture, multitrauma and psychological distress) and dependent variables (Physical Component and Mental Component summary scores of the SF-36). Independent variables that revealed significance (p < 0.05) were entered into a multivariate regression model. For variables found to be significantly associated with SF- 36 Mental Component and Physical Component summary scores, we summarized mean scores across subcategories of the variable. We used Student's t tests and single factor analysis of variance to compare mean scores across categories. To account for multiple significance testing, we used the least squares difference approach to correct our p values. All tests were 2-tailed. Our sample size required a total of 199 patients to assure an 80% probability to detect a relation (0.3 units per unit change) between the independent and dependant variables at a 2-sided 5% significance level (α = 0.05). Our calculation was based on the assumption that the SD of the independent (SCL-90-R score) and dependant (SF-36 score) variable were 10 and 15, respectively. Further, a sample size of 199 patients would be sufficient to evaluate at least 10 variables in the multivariate analysis (assuming 10–20 patients for every variable included in the analysis).

Results

Of 375 patients attending fracture clinics, 125 patients were not actively being followed for a fracture(s). We excluded 15 more patients after the initial interview (10 were under age 16 years and 5 did not speak English). A further 20 eligible patients refused to participate. Thus 215 patients completed the study, giving a response rate of 91.5% (215/235).

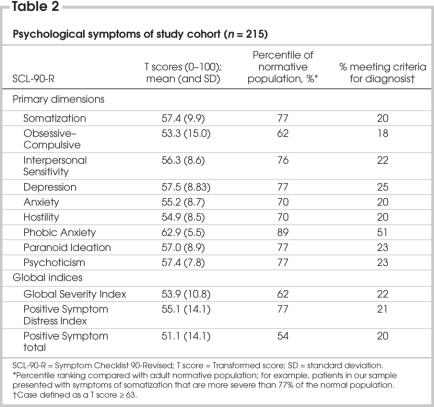

The characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. Study patients had a mean age of 44.5 (SD 18.8) years, 59% were men, and 62% had secondary school or less education. Over one-half (54%) had fractures of their lower extremities, of which the majority were isolated injuries (95%). Injuries had occurred from 1 week to 18 years prior to the time of patient evaluation. During the study period, 24% of patients had filed a disability claim, and 14% had ongoing litigation. Surgeons deemed the technical aspects of reducing the patients' fractures to be successful 94% of the time.

Table 1

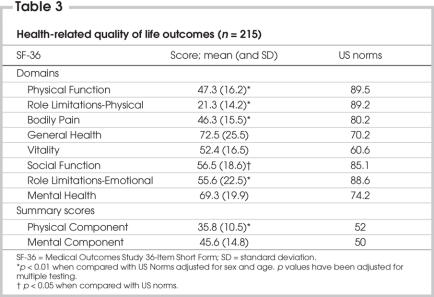

Of the patients, 47 (22%) met the diagnostic threshold for psychological distress (Global Severity Index, Table 2). Patients experienced higher levels of psychological distress in all primary dimensions of the SCL-90-R and scored in the 62nd to 89th percentiles for psychological symptoms, compared with the normal population (Table 2). Phobic anxiety was particularly problematic for patients, placing them in the 89th percentile of the age-and sex-matched population control subjects. Patients also ranked high (77th percentile) for somatization (i.e., the expression of emotional or psychological distress as physical symptoms) (Table 2). Study patients also experienced an increased intensity of psychological symptoms (Positive Symptom Distress Index = 77th percentile). Patients followed for 1 year or more (n = 114) from the time of injury did not significantly differ in their overall distress when compared with those followed for less than 1 year (n = 101) (Global Severity Index 54, SD 10, v. 54, SD 11; Positive Symptom Distress 54, SD 10, v. 56, SD 10; Positive Symptom Total 49, SD 14, v. 54, SD 13).

Table 2

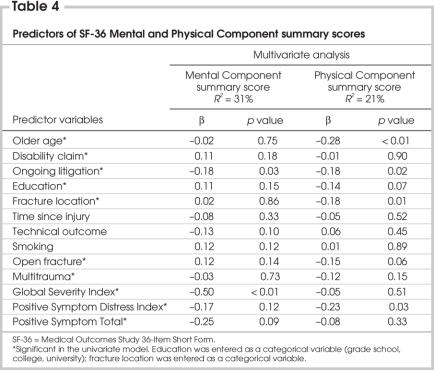

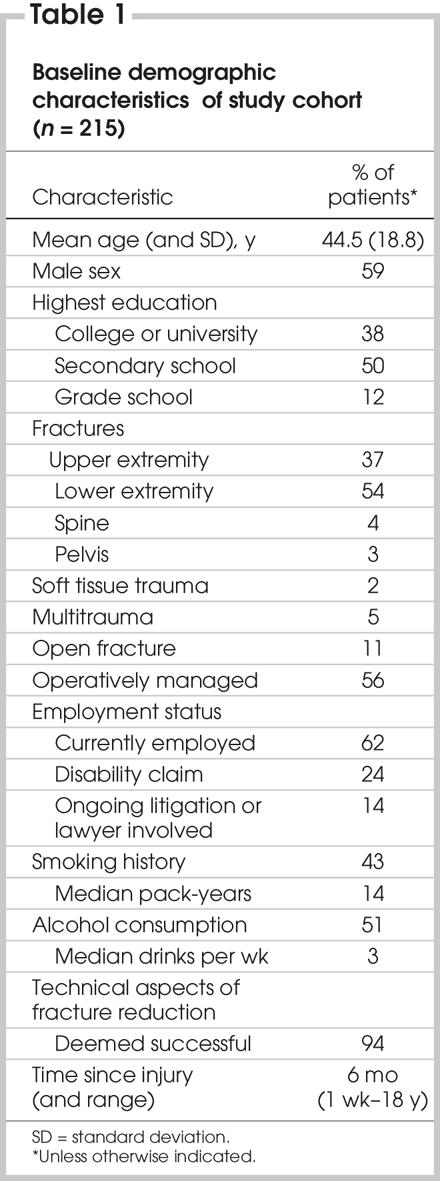

The patients' health-related quality of life, as measured by the SF-36, is presented in Table 3. Study patients experienced significantly decreased Physical Component summary scores, compared with US norms (35.8 v. 52 points, respectively; p < 0.01). Mental Component summary scores were similar to US norms (45.6 v. 50 points, respectively). Using multivariate regression analysis (Table 4), we identified 2 variables associated with reduced Mental Component summary scores: ongoing litigation from the injury (p = 0.03) and global severity of psychological symptoms (p < 0.001). These variables explained 31% of the variability in the Mental Component summary scores of the SF-36 (R2 = 0.31). We identified 4 variables associated with the Physical Component summary scores of the SF-36: older age (p < 0.001), ongoing litigation from the injury (p = 0.02), fracture location (p = 0.01) and the Positive Symptom Distress Index (p = 0.003). These variables explained 21% of the variability in patients' Physical Component summary scores. Patients with upper extremity fractures had higher Physical Component summary scores than patients with lower extremity fractures (39.3, SD 9.8, v. 33.9, SD 10.5; p = 0.03). Open fractures approached statistical significance in their association with Physical Component summary scores (p = 0.06).

Table 3

Table 4

We explored the relation between patients' psychological symptoms and their Mental Component and Physical Component summary scores. The degree to which patients experienced somatoform-like symptoms (i.e., distress arising from perceptions of bodily dysfunction; pain with discomfort of the gross musculature, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory and other systems) was significantly associated with their Physical Component summary score (p = 0.02). Patients' Mental Component summary scores were significantly associated with their degree of interpersonal sensitivity (p = 0.02), phobic anxiety (p = 0.007) and psychoticism (p = 0.01).

Discussion

Our study of 215 patients with orthopedic trauma found the following:

• 1 in 5 patients met the criteria for a psychological illness (22%).

• Patients experienced higher than normal levels of psychological distress in all primary dimensions of the SCL 90-R, especially phobic anxiety and somatization.

• Patients' SF-36 Mental Component summary scores were significantly associated with ongoing litigation and global severity of their psychological symptoms.

• Patients' SF-36 Physical Component summary scores were significantly associated with older age, ongoing litigation, the location of the fracture and the intensity of their psychological symptoms.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is strengthened by the high rate of response from a consecutive group of patients attending for management of orthopedic trauma. Our multivariate regression models were comprehensive and considered injury characteristics, legal and compensation factors, psychological variables and sociodemographic characteristics, which provides greater confidence in our results. We used SF-36 summary scores as our dependant variables because functional status and health-related quality of life are outcomes of primary importance to patients. Our decision to include all orthopedic trauma involving fractures across multiple clinics increases the generalizability of our findings. However, these findings may not generalize to non–university-based fracture clinics.

Our study does have limitations. We acquired both potentially predictive variables and outcomes at the same time, which does not allow us to assess causation. It could be argued that people who suffer more severe orthopedic trauma or whose clinical management is less successful are more likely to develop psychological symptoms, have worse functional outcomes (as indicated by SF-36 scores) and pursue legal action. However, length of time since injury, technical outcome of management, multitrauma and having an open as opposed to a closed fracture were not associated with SF-36 scores. Further, our study did not account for complications, time to healing and hospital readmissions as possible variables affecting both outcome and psychosocial disability. We did not collect data on psychological morbidity prior to injury, and it is not clear to what degree postinjury distress can be attributed to the injury. Although epidemiologic studies suggest that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the general community is about 20%,30 our study design did not allow for assessment of psychological distress before injury. Thus our findings cannot rule out the possibility of preexisting psychiatric illness. Although we asked patients about alcohol consumption, level of education and smoking status, patients might not have reported these variables accurately, leading to social desirability bias.31 A prospective cohort study having multiple follow-up assessments over time that incorporate insights from this study is needed to further resolve this issue.

Relevant literature

Our finding that 22% of the patients with orthopedic injuries satisfy criteria for psychological illness is consistent with previous reports. Mason and colleagues11 assessed the psychological state of 210 male accident and emergency department patients and followed them for 18 months, at which time 30% satisfied criteria for a psychiatric disorder. A recent study of patients with severe lower limb injuries found a 42% prevalence of psychological disorder at 24-month follow-up and that only 22% of such patients reported receiving mental health services.12 No relation was found between injury severity and psychological distress; however, the authors suggested that low variability in injury severity might have obscured this result. McCarthy and colleagues further identified a high correlation between the Brief Symptom Inventory (a measure of psychological distress) and the Sickness Impact Profile (a measure of patient function).

The correlation between psychological distress and physical complaints has been reported by several authors.32–36 Zatzick and colleagues32 also compared psychological distress and health-related quality of life in 101 hospitalized trauma patients. One year after injury, 30% of the patients (n = 22) met symptomatic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Compared with patients without PTSD, patients with PTSD demonstrated significant adverse outcomes in 7 of the 8 domains of the SF-36.32 In a survey of 2606 patients with shoulder pain, Badcock and colleagues identified that psychological distress scores correlated significantly with physical complaints of pain (p = 0.002).34 In another study, Cho and colleagues identified significant differences in prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms between students (n = 471) with high and low psychological distress levels.35

Starr and colleagues conducted a study of 588 patients and found that 51% of patients met criteria for PTSD.9 Specifically, patients scored higher on questions pertaining to avoidance (“cannot enjoy the company of others,” “cannot enjoy things I used to”). These results parallel our findings that patients reported greater difficulty with interpersonal relationships (i.e., interpersonal sensitivity). Our study further identified that lower Mental Component summary scores were significantly associated with phobic anxiety and psychoticism. We also found that decreased Physical Component summary scores were significantly associated with somatization disturbances (i.e., generalized feelings of weakness, nausea and dizziness).

Our study found that ongoing litigation was associated with reduced quality of life, and this may be due to greater injury severity, to the patient's reporting of disability when litigation was initiated (the preservation effect) or to the stress of litigation.15 MacDermid and colleagues followed 120 patients with distal radial fractures for 6 months after injury.16 After adjusting for age, sex, education level, Müller AO fracture classification and pre-and postreduction radial shortening, the strongest predictor of pain and disability was the combined variable of ongoing litigation or claiming compensation. Other prospective studies on distal radial fractures have also found that objective clinical variables provide limited prediction for posttrauma disability.36

Michaels and colleagues surveyed 247 trauma patients without significant neurotrauma at 1 year postinjury.13 They found significant negative associations between ongoing litigation and workers' compensation claims and functional scores (Sickness Impact Profile subscales).13 Mock and colleagues17 followed a cohort of 302 patients with lower extremity fractures over a 1-year period and found that the degree of physical impairment predicted only a small amount of the variance in disability. Significant predictors of disability were older age, lower socioeconomic status, poor health prior to injury, low social support, having hired a lawyer and involvement with workers' compensation.

Relevance of our findings

Our study confirms previous findings that psychological disorders are common among orthopedic trauma patients.12,37 We have extended these findings to patients with both isolated and multiple injuries and demonstrated the association between psychological symptoms and health-related quality of life. Clinical variables, aside from fracture location, were not associated with SF-36 summary scores; however, the global severity of psychological symptoms and ongoing litigation predicted poorer Mental Component summary scores. The Physical Component summary score was predicted by the intensity of psychological distress. Management of comorbid psychological illness has had important positive effects on recovery from trauma from sexual abuse, spousal abuse, head injury and critical illness.38–41 It remains plausible that orthopedic trauma patients presenting with comorbid psychopathology may experience similar benefits. Previous work has reported that mental illness is an independent predictor of poor outcome following orthopedic trauma, and future studies should explore whether management of psychological symptoms independently predicts recovery from orthopedic trauma. Our findings add to a growing body of literature that suggests psychological symptoms among orthopedic trauma patients may be an important target for intervention.33,42

Conclusion

Our survey of orthopedic trauma patients found that 1 in 5 patients met the criteria for psychological illness. Psychosocial factors, specifically, ongoing litigation and psychological symptoms, were associated with reduced health-related quality of life. Clinical variables had little predictive ability. Our results suggest that psychological morbidity and pursuit of litigation are associated with health-related quality of life after fracture.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by research grants from AO North America and Regional Medical Associates, McMaster University. Dr. Bhandari was funded in part by a 2004 Detweiler Fellowship, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Dr. Busse is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship Award.

Competing interests: None declared.

Accepted for publication Mar. 7, 2006

Correspondence to: Dr. Mohit Bhandari, CLARITY Research Group, Hamilton General Hospital, 6 North Trauma, 237 Barton St. E, Hamilton ON L8L 2X2; bhandam@mcmaster.ca

References

- 1.Trunkey DD. Trauma care systems. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1984;2:913-22. [PubMed]

- 2.Russell TA. Fractures of the tibial diaphysis. In: Levine AM, editor. Orthopaedic knowledge update trauma. Rosemont (IL): American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996. p. 171-9.

- 3.Committee on Injury Prevention and Control; Institute of Medicine. Reducing the burden of injury: advancing prevention and treatment. Washington: National Academy Press; 1999.

- 4.Moed BR, Yu PH, Gruson KI. Functional outcomes of acetabular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A:1879-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Pollak AN, McCarthy ML, Bess RS, et al. Outcomes after treatment of high-energy tibial plafond fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A:1893-900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Adams JE, Davis G, Alexander CB, et al. Pelvic trauma in rapidly fatal motor vehicle accidents. J Orthop Trauma 2003; 17:40610. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Richmond J, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, et al. Mortality risk after hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2003;17(Suppl): S2-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Rusch MD. Psychological response to trauma. Plast Surg Nurs 1998;18:147-52. [PubMed]

- 9.Starr AJ, Smith W, Frawley W, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder after orthopaedic trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1115-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dijkstra PU, Groothoff JW, ten Duis HJ, et al. Incidence of complex regional pain syndrome type I after fractures of the distal radius. Eur J Pain 2003;7:457-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Mason S, Wardrope J, Turpin G, et al. The psychological burden of injury: an 18 month prospective cohort study. Emerg Med J 2002;19:400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.McCarthy ML, MacKenzie EJ, Edwin D, et al. LEAP study group. Psychological distress associated with severe lower-limb injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85: 1689-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Smith JS, et al. Outcome from injury: general health, work status, and satisfaction 12 months after trauma. J Trauma 2000;48:841-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Moon C, et al. Psychosocial factors limit outcomes after trauma. J Trauma 1998;44:644-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Suter PB. Employment and litigation: improved by work, assisted by verdict. Pain 2002; 100:249-57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.MacDermid JC, Donner A, Richards RS, et al. Patient versus injury factors as predictors of pain and disability six months after a distal radius fracture. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:849-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mock C, MacKenzie E, Jurkovich G, et al. Determinants of disability after lower extremity fracture. J Trauma 2000;49: 1002-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Derogatis LR. Symptom Checklist-90R: administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1994.

- 19.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock A. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self report scale. Br J Psychiatry 1976;128:280-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Horowitz LM, Rosenberg S, Baer B, et al. Inventory and interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56: 885-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Derogatis L. Breast and gynecological cancers: their unique impact on body image and sexual identity in women. In: Vaeth JM, editor. Body image, self esteem, and sexuality in cancer patients. Basel (Switzerland): Karger; 1980.

- 22.Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham (NC): Duke University Press; 1992.

- 23.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 1992;305:160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Rogers W, et al. The validity and relative precision of MOS short-and long-form health status scales and Dartmouth COOP charts. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1992;30(Suppl):MS253-65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473-83. [PubMed]

- 26.Ponzer S, Nasell H, Bergman B, et al. Functional outcome and quality of life with patients with Type B ankle fractures: A two year follow up study. J Orthop Trauma 1999;13:363-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Bhandari M, Sprague S, Hanson B, et al. Health-related quality of life following operative treatment of unstable ankle fractures: a prospective observational study. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18:338-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Derogatis LR, Morrow G, Fetting J, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 1983; 249: 751-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Peveler RC, Fairburn C. Measurement of neurotic symptoms by self-report questionnaire: validity of the SCL-90R. Psychol Med 1990;20:873-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62: 593-602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Fisher RF. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res 1993;20:303-15.

- 32.Zatzick DF, Jurkovich GJ, Gentilello L, et al. Posttraumatic stress, problem drinking, and functional outcomes after injury. Arch Surg 2002;137:200-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Dyrehag LE, Widerstrom-Noga EG, Carlsson SG, et al. Relations between self-rated musculoskeletal symptoms and signs and psychological distress in chronic neck and shoulder pain. Scand J Rehabil Med 1998; 30:235-42. [PubMed]

- 34.Badcock LJ, Lewis M, Hay EM, et al. Chronic shoulder pain in the community: a syndrome of disability or distress? Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:128-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Cho CY, Hwang IS, Chen CC. The association between psychological distress and musculoskeletal symptoms experienced by Chinese high school students. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2003;33:344-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Karnezis IA, Fragkiadakis EG. Association between objective clinical variables and patient-rated disability of the wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:967-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Nightingale S, Holmes J, Mason J, et al. Psychiatric illness and mortality after hip fracture. Lancet 2001;357:1264-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Zun LS, Downey LV, Rosen J. Violence prevention in the ED: linkage of the ED to a social service agency. Am J Emerg Med 2003;21:454-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Degeneffe CE. Family caregiving and traumatic brain injury. Health Soc Work 2001; 26:257-68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Albert SM, Im A, Brenner L, et al. Effect of a social work liaison program on family caregivers to people with brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2002;17:175-89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Delva D, Vanoost S, Bijttebier P, et al. Needs and feelings of anxiety of relatives of patients hospitalized in intensive care units: implications for social work. Soc Work Health Care 2002;35:21-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Holmes J, House A. Psychiatric illness predicts poor outcome after surgery for hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Psychol Med 2000;30:921-9. [DOI] [PubMed]