Abstract

Background and objectives: Emerging information indicates that glucose metabolism alterations are common after renal transplantation and are associated with carotid atheromatosis. The aims of this study were to investigate the prevalence of different glucose metabolism alterations in stable recipients as well as the factors related to the condition.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A multicenter, cross-sectional study was conducted of 374 renal transplant recipients without pre- or posttransplantation diabetes. A standard 75-g oral glucose tolerance test was performed.

Results: Glucose metabolism alterations were present in 119 (31.8%) recipients: 92 (24.6%) with an abnormal oral glucose tolerance test and 27 (7.2%) with isolated impaired fasting glucose. The most common disorder was impaired glucose tolerance (17.9%), and an abnormal oral glucose tolerance test was observed for 21.5% of recipients with a normal fasting glucose. By multivariate analysis, age, prednisone dosage, triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, and β blocker use were shown to be factors related to glucose metabolism alterations. Remarkably, triglyceride levels, triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, and the proportion of recipients with impaired fasting glucose were already higher throughout the first posttransplantation year in recipients with a current glucose metabolism alteration as compared with those without the condition.

Conclusions: Glucose metabolism alterations are common in stable renal transplant recipients, and an oral glucose tolerance test is required for its detection. They are associated with a worse metabolic profile, which is already present during the first posttransplantation year. These findings may help planning strategies for early detection and intervention.

New-onset diabetes after renal transplantation (NODAT) represents a serious metabolic complication with a negative impact on graft and patient survival, as well as on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1–5). Emerging information indicates that less severe glucose metabolism alterations (GMA), such as impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), are also highly prevalent (6–10) and are associated with increased cardiovascular risk in the general population (11,12). In the renal transplant setting, Cosio et al. (13) reported that IFG was associated with a significantly higher incidence of posttransplantation cardiac events and peripheral vascular disease. In addition, an abnormal oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in stable renal transplant recipients is related to carotid atheromatosis (14), a surrogate marker of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Recently developed consensus guidelines have suggested that the diagnosis of GMA in renal transplant recipients should be based on regular screening of fasting blood glucose (1); however, other studies demonstrated that such an approach underestimated the true incidence of NODAT and ignored the important diagnosis of IGT, which can be made only with a simple and inexpensive OGTT (6–10). Single-center studies have reported that stable renal transplant recipients with IFG and/or IGT are older, exhibit higher body mass index and dyslipidemia, and more frequently are on β blockers (6–8); however, multicenter studies including a higher number of patients and reflecting different clinical practices may contribute to more accurate characterization of the clinical profile of recipients with GMA. Because these conditions are modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, providing the clinician with simple tools to suspect the condition may be helpful to indicate a more thorough investigation with OGTT and apply preventive interventions. The aims of this multicenter, cross-sectional study were to investigate the prevalence of GMA beyond 1 yr of transplantation and, in addition, the clinical profile and factors related to these conditions.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

For this cross-sectional, multicenter study, each participating center recruited 30 to 50 consecutive stable renal transplant recipients who attended the outpatient clinic, did not have pretransplantation diabetes, and had >1 yr of functioning graft. Eight Spanish transplant centers participated in the study. The only selection criterion was the patient's acceptance to participate in the study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Among 426 initially recruited recipients, 52 were excluded because they fulfilled the American Diabetes Association criteria of new-onset diabetes (fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl or the use of antidiabetic medications). The remaining 374 patients (50 ± 13 yr; 65% male) underwent a standard OGTT.

Data concerning demographic information, previous cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart disease, cerebral vascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease, diagnosed by standard criteria), type and time on dialysis, primary renal disease, donor and transplant characteristics, immunosuppressive drugs, and other treatments were recorded from patients’ charts, in accordance with Spanish law on the protection and confidentiality of clinical data.

Maintenance immunosuppression was based on a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) in 90% of recipients. The most common treatment combinations were prednisone + tacrolimus + mycophenolate mofetil (n = 118) and prednisone + cyclosporin A + mycophenolate mofetil (n = 89). Sirolimus was used in 35 (9%) recipients: In 27 (7%) cases without CNI and in eight (2%) as an adjuvant with CNI. Most (91%) patients were receiving corticosteroids.

Definition of GMA

A standard OGTT was done after an overnight 10- to 12-h fast. Blood samples were obtained before and 2 h after 75 g of glucose administration. GMA were classified on the basis of fasting and 2-h glucose levels following the American Diabetes Association criteria (15): IFG (fasting glucose ≥100 and ≤125 mg/dl), IGT (2-h glucose 140 to 199 mg/dl), and provisional diagnosis of diabetes (2-h glucose ≥200 mg/dl). Because a second OGTT was not routinely performed for patients with a provisional diagnosis of diabetes to confirm the diagnosis of NODAT, for the purpose of this study, IFG, IGT, and a provisional diagnosis of diabetes were considered GMA.

Determinations

Fasting plasma glucose, triglycerides (Tg), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol levels were measured at the time of OGTT using a computerized autoanalyzer in each study center. We also retrospectively obtained the values of these parameters at 3, 6, and 12 mo after transplantation. The Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio was used as a marker of insulin resistance (16). Glycated hemoglobin was measured by HPLC in each study center at the time of OGTT. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m).

Renal function was assessed by serum creatinine and the Jelliffe formula to estimate creatinine clearance: Creatinine clearance (ml/min) = {[98 − (0.8 × age −20)/20]/serum creatinine} × 0.90 if female. This formula compares favorably with others in terms of dispersion when compared with inulin clearance in the renal transplant population (17). Proteinuria was measured from a 24-h urine collection.

Cyclosporin A and tacrolimus levels were quantified by fluorescence polarization immunoassay using a mAb (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott, IL).

Statistical Analyses

For normally distributed variables, data are presented as means ± SD, and for non-normally distributed variables as median and interquartile range. For comparison of recipients with or without GMA, t test or Mann-Whitney test was used as appropriate. Pearson χ2 test was used to compare proportions between groups.

For identification of independent factors related to GMA, a backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed. Age; gender; family history of diabetes; weight gain during transplantation; smoker status; and current BMI, prednisone dosage, estimated creatinine clearance, lipid metabolism parameters, type of CNI, and the use of statins, β blockers, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, or antiplatelet drugs were included.

P < 0.05 was considered significant in the statistical analysis. Computations were carried out using the SPSS 13.0 for Windows statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Prevalence of GMA

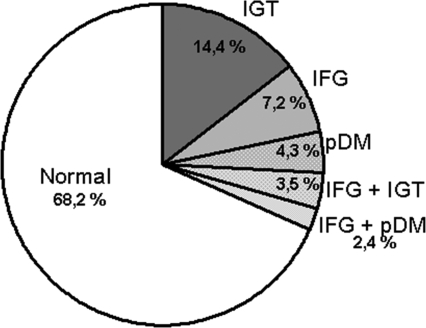

A total of 119 (31.8%) patients had a GMA: 92 (24.6%) showed an abnormal OGTT, and 27 (7.2%) had isolated IFG. The distribution of different GMA is depicted in Figure 1. The most common disorder was IGT (17.9%) alone (14.4%) or combined with IFG (3.5%). With a prevalence of 7.2%, isolated IFG was a less common disorder, and a provisional diagnosis of diabetes was given to 6.7% of the cases. Remarkably, 70 (58.8%) of 119 recipients with a GMA, showed a normal fasting glucose (<100 mg/dl). Conversely, an abnormal OGTT was observed in 70 (21.5%) of 325 recipients with a normal fasting glucose.

Figure 1.

Distribution of various glucose metabolism alterations in stable renal transplant patients. IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; pDM, provisional diabetes.

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Profile of Renal Transplant Recipients with GMA

Recipients with a GMA were generally older and had sustained more pre- and posttransplantation cardiovascular events, as compared with normal (Table 1). Of note, they also had a higher prednisone dosage, poorer renal function, and more severe hypertension, as assessed by the required number of antihypertensive drugs. In addition, a higher proportion of recipients with a GMA were treated with β blockers and diuretics.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and transplant-related data of patients with NGM or a GMAa

| Parameter | NGM(n = 252) | GMA(n = 119) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 47 ± 13 | 54 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 63 | 69 | NS |

| Posttransplantation time (yr; median [range]) | 3.5 (2 to 5) | 4.1 (2.6 to 5.5) | NS |

| Dialysis duration (mo; median [range]) | 18.5 (11 to 35) | 22 (12 to 34) | NS |

| Previous cardiovascular events (%) | 5.4 | 15 | 0.003 |

| Posttransplantation cardiovascular events (%) | 6.3 | 14 | 0.016 |

| HCV (%) | 2.7 | 5.9 | NS |

| Family history of type 2 diabetes (%) | 20 | 29 | 0.069 |

| Current smoker (%) | 16 | 12 | NS |

| CsA (%) | 38 | 44 | NS |

| TAC (%) | 53 | 52 | NS |

| Sirolimus (%) | 11 | 6 | NS |

| CsA levels (ng/ml; mean ± SD) | 126.8 ± 50.7 | 128.4 ± 52.6 | NS |

| TAC levels (ng/ml; mean ± SD) | 8.0 ± 3.0 | 7.9 ± 2.4 | NS |

| MMF (%) | 66 | 62 | NS |

| Corticosteroid withdrawal (%) | 6.8 | 4.2 | NS |

| Prednisone dosage (mg/d; mean ± SD) | 5.23 ± 2.21 | 6.16 ± 2.78 | 0.004 |

| Prednisone dosage >5 mg/d (%) | 19 | 31 | 0.014 |

| Acute rejection (%) | 17 | 18 | NS |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/min; median [range]) | 53 (41 to 69) | 46 (37 to 61) | 0.006 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl; median [range]) | 1.34 (1.1 to 1.8) | 1.43 (1.11 to 1.90) | NS |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h; median [range]) | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.18) | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.17) | NS |

| Systolic BP (mmHg; median [range]) | 130 (120 to 140) | 136 (120 to 147) | NS |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg; median [range]) | 80 (74 to 85) | 79 (70 to 84) | NS |

| ≥3 Antihypertensive drugs (%) | 26 | 37 | 0.022 |

| Diuretics (%) | 23 | 34 | 0.023 |

| β Blockers (%) | 33 | 56 | <0.001 |

| Carvedilol (%) | 36 | 41 | NS |

| ACEI/ARB (%) | 52 | 47 | NS |

| Antiplatelet drugs (%) | 27 | 42 | 0.005 |

| Statins (%) | 55 | 64 | NS |

GMA include impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and provisional diagnosis of diabetes. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers, CsA, cyclosporin A; GMA, glucose metabolism alteration; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; NGM, normal glucose metabolism; TAC, tacrolimus.

The metabolic profile of both groups of recipients is outlined in Table 2. Recipients with a GMA had higher BMI and had gained more weight since transplantation. Tg and the Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio but not other lipid parameters were significantly higher in this group. As expected, fasting glucose, glucose after OGTT, and glycated hemoglobin levels were significantly higher in recipients with a GMA. Importantly, this pattern of alterations was already present throughout the first posttransplantation year (Table 2). As a consequence, IFG at 3, 6, and 12 mo after transplantation was more common among recipients with current GMA (Table 2), showing the early onset of these disorders.

Table 2.

Metabolic characteristics of recipients with NGM or a GMA

| Characteristic | NGM(n = 252) | GMA(n = 119) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 26.5 ± 4.5 | 28.0 ± 4.3 | 0.010 |

| BMI increase after transplantation (median [range]) | 1.65 (0.45 to 3.48) | 2.91 (1.19 to 4.40) | 0.003 |

| Weight gain after transplantation (kg; median [range]) | 4.5 (1.3 to 9.8) | 7.7 (3.0 to 12.0) | 0.006 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 189 ± 33 | 190 ± 32 | NS |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 103 ± 28 | 99 ± 28 | NS |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl; median [range]) | 56 (47 to 69) | 53 (43 to 65) | NS |

| Tg (mg/dl; median [range]) | 117 (84 to 150) | 147 (105 to 183) | <0.001 |

| Tg/HDL cholesterol (median [range]) | 2.05 (1.30 to 2.90) | 2.80 (1.70 to 3.70) | <0.001 |

| OGTT glucose 0 (mg/dl; median [range]) | 87 (81 to 94) | 99 (91 to 104) | <0.001 |

| OGTT glucose 120 (mg/dl; median [range]) | 101 (85 to 117) | 160 (140 to 193) | <0.001 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%; median [range]) | 5.2 (4.8 to 5.6) | 5.5 (5.0 to 5.9) | <0.001 |

| First posttransplantation year profile | |||

| 3-mo glucose (mg/dl; median [range]) | 90 (81 to 100) | 96 (86 to 106) | <0.001 |

| 3-mo IFG (%) | 24 | 40 | 0.005 |

| 6-mo glucose (mg/dl; median [range]) | 88 (81 to 95) | 94 (86 to 104) | <0.001 |

| 6-mo IFG (%) | 16 | 31 | 0.002 |

| 12-mo glucose (mg/dl; median [range]) | 86 (81 to 93) | 94 (87 to 103) | <0.001 |

| 12-mo IFG (%) | 10 | 37 | <0.001 |

| transient NODAT (first year; %) | 5.9 | 3.4 | NS |

| 3-mo Tg (mg/dl; median [range]) | 128 (91 to 171) | 147 (106 to 183) | 0.050 |

| 6-mo Tg (mg/dl; median [range]) | 119 (89 to 172) | 135 (105 to 173) | 0.050 |

| 12-mo Tg (mg/dl; median [range]) | 112 (88 to 157) | 149 (115 to 186) | <0.001 |

| 12-mo Tg/HDL cholesterol (median [range]) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.1) | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.6) | 0.005 |

| 12-mo Total cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 198 ± 35 | 199 ± 30 | NS |

| 12-mo HDL cholesterol (mg/dl; median [range]) | 55 (45 to 68) | 56 (46 to 68) | NS |

| 12-mo LDL cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 114 ± 38 | 111 ± 29 | NS |

aGMA include IFG, IGT, and provisional diagnosis of diabetes. BMI, body mass index. OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; NODAT, new-onset diabetes after transplantation; Tg, triglycerides.

Factors Associated with GMA

Finally, we assessed the factors related to the observed GMA. By multiple logistic regression analysis, the use of β blockers, current Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio, prednisone dosage, and age were identified as factors that were independently associated with GMA after adjustment for other variables (Table 3). When Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio was replaced by Tg levels, statistical significance was almost reached, with an odds ratio of 1.26 per each 50-mg/dl increase of Tg (95% confidence interval 1.00 to 1.59; P = 0.05).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showing factors associated with GMA (IFG, IGT, or provisional diagnosis of diabetes)a

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| β Blocker use | 2.67 | 1.50 to 4.75 | <0.001 |

| Tg/HDL cholesterol | 1.28 | 1.06 to 1.54 | 0.010 |

| Prednisone dosage (mg/d) | 1.12 | 1.00 to 1.25 | 0.046 |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine clearance | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.173 |

Other tested variables were gender; family history of diabetes; weight gain; smoking status; current BMI; creatinine clearance; BP; lipid metabolism parameters; and use of statins, diuretics, ACEI/ARB, antiplatelet drugs, calcineurin inhibitor (and type), and MMF. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that one in three stable renal transplant recipients beyond the first posttransplantation year develops a GMA, which is associated with an adverse cardiovascular profile. In a substantial proportion (59%) of these recipients, a normal fasting glucose level coexists with an abnormal OGTT. Factors that were independently related to these alterations were age, current corticosteroid dosage, Tg levels and Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio, and the use of β blockers. Remarkably, recipients with a current GMA already presented higher fasting glucose and Tg levels throughout the first posttransplantation year as compared with recipients with normal glucose metabolism.

The observed 24.6% prevalence of abnormal OGTT in our study was in the lower range of the 23 to 50%, which was reported by others (6–8,10); however, taking into account that 80% of our patients were beyond the second posttransplantation year, when immunosuppression is consistently reduced, the prevalence of GMA may still be considered high. Noteworthy, a substantial proportion of our recipients with these alterations (59%) showed an abnormal OGTT in the presence of normal fasting glucose; therefore, this finding confirms that the sole use of fasting glucose as screening underestimates the true incidence of GMA. Because these alterations have been related to cardiovascular events (13) and carotid atheromatosis (14), consideration should be given to introducing the OGTT as a routine investigation in renal transplant recipients.

By examining fasting glucose levels, Cosio et al. (13) reported a prevalence of IFG at first posttransplantation year of 33%, without a significant change after a minimum follow-up of 2 yr. The prevalence of IFG in our study after a mean posttransplantation time of 3.9 yr was 13% (Figure 1). Although there is no apparent explanation for this difference, the true incidence of GMA was probably underestimated in the study by Cosio et al., because glucose levels after an OGTT were not investigated.

Our recipients with GMA showed many components of the metabolic or insulin resistance syndrome. They were more obese, had higher fasting glucose and Tg levels, and had more severe hypertension than recipients with normal glucose metabolism. In fact, a higher proportion of them had a history of cardiovascular events both before and after transplantation, suggesting that the condition could be already present at earlier stages of renal disease.

The corticosteroid dosage during current treatment was higher in recipients with GMA, and a higher proportion of them were receiving >5 mg/d prednisone as compared with recipients with normal glucose metabolism. In addition, corticosteroid dosage was independently related to these alterations in the multivariate analysis (Table 3), which demonstrates the importance of corticosteroid withdrawal or minimization after transplantation. Age was an additional independent factor related to GMA, as has been reported in other studies (6,7).

Current Tg levels and Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio, both clinically useful markers of insulin resistance (16,18), were higher in recipients with GMA (Table 2) and independently related to the condition (Table 3). In addition, these abnormalities, along with a more common diagnosis of IFG, were already detected at 3 mo, persisting during the first posttransplantation year (Table 2), and may have contributed to the higher rate of posttransplantation cardiovascular events in this group (Table 1). A similar observation was reported by Cosio et al. (13), who showed that recipients with NODAT or IFG at 1 yr exhibited higher fasting glucose levels from the first month after transplantation; therefore, these findings suggest that an OGTT may be especially indicated in recipients who have hypertriglyceridemia and/or IFG by the end of the third month after transplantation (10).

Recipients with GMA were more likely on β blockers than those with normal glucose metabolism (Table 1), as has been previously reported (7,9). It is interesting that this group of drugs was shown to induce insulin resistance and reduce adiponectin levels in renal transplant recipients (19).

Our study has limitations. First, its cross-sectional design makes it difficult to discern any definitive cause–effect relationship. Second, our population was predominantly white, so our findings may not be directly applicable to other race groups. Third, 91% of patients were taking glucocorticosteroids, and the results therefore cannot be extrapolated to recipients who are not taking them. Finally, we could not provide information about other factors that may have contributed to GMA, such as lifestyle habits and diet.

Despite these limitations, we can draw the following conclusions from this study. GMA are common beyond 1 yr of transplantation and are associated with an impaired cardiovascular profile. An OGTT is required to detect the full expression of these conditions. Age, corticosteroid dosage, the use of β blockers, and the Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio are independently related to these alterations. Importantly, the presence of IFG, hypertriglyceridemia, or an elevated Tg/HDL cholesterol ratio during the first posttransplantation year may alert clinicians about the risk for an occult GMA, favoring its early detection and therapeutic intervention.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants RedInRen, C03/03 (Spanish Network for Transplantation Research) and FIS 04/0988, from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Health). P.D. works as a research fellow, supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CM06/00232, Spanish Ministry of Health).

Preliminary results of this study were presented in a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology; October 31–November 5, 2007, San Francisco, CA.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Davidson J, Wilkinson A, Dantal J, Dotta F, Haller H, Hernández D, Kasiske BL, Kiberd B, Krentz A, Legendre C, Marchetti P, Markell M, van der Woude FJ, Wheeler DC: International Expert Panel: New-onset diabetes after transplantation: 2003 International consensus guidelines. Proceedings of an international expert panel meeting. Barcelona, Spain, 19 February 2003. Transplantation 75: SS3–SS24, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montori VM, Basu A, Erwin PJ, Velosa JA, Gabriel SE, Kudva YC: Posttransplantation diabetes: A systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 25: 583–592, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles AM, Sumrani N, Horowitz R, Homel P, Maursky V, Markell MS, Distant DA, Hong JH, Sommer BG, Friedman EA: Diabetes mellitus after renal transplantation: As deleterious as non-transplant-associated diabetes? Transplantation 65: 380–384, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosio FG, Pesavento TE, Kim S, Osei K, Henry M, Ferguson RM: Patient survival after renal transplantation: IV. Impact of post-transplant diabetes. Kidney Int 62: 1440–1446, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Leivestad T, Holdaas H, Sagedal S, Olstad M, Jenssen T: The impact of early-diagnosed new-onset post-transplantation diabetes mellitus on survival and major cardiac events. Kidney Int 69: 588–595, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong KA, Prins JB, Beller EM, Campbell SB, Hawley CM, Johnson DW, Isbel NM: Should an oral glucose tolerance test be performed routinely in all renal transplant recipients? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 100–108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharif A, Moore RH, Baboolal K: The use of oral glucose tolerance tests to risk stratify for new-onset diabetes after transplantation: An underdiagnosed phenomenon. Transplantation 82: 1667–1672, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nam JH, Mun JI, Kim SI, Kang SW, Choi KH, Park K, Ahn CW, Cha BS, Song YD, Lim SK, Kim KR, Lee HC, Huh KB: β-Cell dysfunction rather than insulin resistance is the main contributing factor for the development of postrenal transplantation diabetes mellitus. Transplantation 71: 1417–1423, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hjelmesaeth J, Midtvedt K, Jenssen T, Hartmann A: Insulin resistance after renal transplantation: Impact of immunosuppressive and antihypertensive therapy. Diabetes Care 24: 2121–2126, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David-Neto E, Lemos FC, Fadel LM, Agena F, Sato MY, Coccuza C, Pereira LM, de Castro MC, Lando VS, Nahas WC, Ianhez LE: The dynamics of glucose metabolism under calcineurin inhibitors in the first year after renal transplantation in nonobese patients. Transplantation 84: 51–55, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saydah SH, Loria CM, Eberhardt MS, Brancati FL: Subclinical states of glucose intolerance and risk of death in the US. Diabetes Care 24: 447–453, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjornholt JV, Erikssen G, Aaser E, Sandvik L, Nitter-Hauge S, Jervell J, Erikssen J, Thaulow E: Fasting blood glucose: an underestimated risk factor for cardiovascular death: Results from a 22-year follow-up of healthy nondiabetic men. Diabetes Care 22: 45–49, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosio FG, Kudva Y, van der Velde M, Larson TS, Textor SC, Griffin MD, Stegall MD: New onset hyperglycemia and diabetes are associated with increased cardiovascular risk after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 67: 2415–2421, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez A, Fernández J, Porrini E, Delgado P, Pitti S, Vega MJ, González-Posada JM, Rodríguez A, Pérez L, Marrero D, Luis D, Velázquez S, Hernández D, Torres A: Carotid atheromatosis in non-diabetic renal transplant recipients: The role of prediabetic glucose homeostasis alterations. Transplantation 84: 870–875, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 27: S5–S10, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLaughlin T, Reaven G, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, Saad M, Waters D, Simon J, Krauss RM: Is there a simple way to identify insulin-resistant individuals at increased risk of cardiovascular disease? Am J Cardiol 96: 399–404, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariat C, Alamartine E, Barthelemy JC, De Filippis JP, Thibaudin D, Berthoux P, Laurent B, Thibaudin L, Berthoux F: Assessing renal graft function in clinical trials: Can tests predicting glomerular filtration rate substitute for a reference method? Kidney Int 65: 289–297, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Midtvedt K, Aakhus S, Stenstrom J, Morkrid L, Egeland T, Tordarson H, Fauchald P: Metabolic cardiovascular syndrome after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 1047–1052, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hjelmesaeth J, Flyvbjerg A, Jenssen T, Frystyk J, Ueland T, Hagen M, Hartmann A: Hypoadiponectinemia is associated with insulin resistance and glucose intolerance after renal transplantation: Impact of immunosuppressive and antihypertensive drug therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 575–582, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]