Abstract

Background and objectives: Lupus nephritis is a classic immune complex glomerulonephritis. In contrast, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are associated with necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis, in the absence of significant immune deposits. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are detected by indirect immunofluorescence in 20% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. We report 10 cases of necrotizing and crescentic lupus nephritis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody seropositivity.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Ten patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity, and renal biopsy findings of lupus nephritis and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated glomerulonephritis were identified. The clinical features, pathologic findings, and outcomes are described.

Results: The cohort consisted of eight women and two men with a mean age of 48.4 yr. Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was detected by indirect immunofluorescence in nine patients. Four of the nine patients and the single remaining patient were found to have myeloperoxidase–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clinical presentation included proteinuria, hematuria, and acute renal insufficiency, with mean creatinine of 7.1 mg/dl. All biopsies exhibited prominent necrosis and crescents with absent or rare subendothelial deposits and were interpreted as lupus nephritis and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated glomerulonephritis. All patients received cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Three patients died of infectious complications. Among the remaining seven patients, five achieved a complete or near-complete remission, one had a remission with subsequent relapse, and one had no response to therapy.

Conclusion: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis may occur superimposed on lupus nephritis. In patients with lupus nephritis and biopsy findings of prominent necrosis and crescent formation in the absence of significant endocapillary proliferation or subendothelial deposits, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is recommended.

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a classic immune complex–mediated renal disease. The formation of glomerular immune deposits results in complement activation; leukocyte infiltration; cytokine release; cellular proliferation; and, in some instances, necrosis, crescent formation, and/or eventual glomerular scarring. The patterns of glomerulonephritis (GN) seen in patients with LN reflect the sites of immune complex deposition (1).

Pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic GN differs from LN in that glomerular necrosis and crescent formation occur in the absence of significant cellular proliferation and in the presence of no more than a “paucity” of glomerular immune complex deposits. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are directly implicated in the pathogenesis of this form of glomerular injury and are thought to directly target cytokine-primed neutrophils that express myeloperoxidase (MPO) or proteinase 3 (PR3) at the cell surface. After activation by MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA, neutrophils release cytokines, toxic oxygen metabolites, and lytic proteinases, leading to endothelial damage with subsequent glomerular basement membrane rupture, necrosis, and crescent formation (2).

In LN, the degree of subendothelial deposit formation roughly correlates with the degree of endocapillary proliferation, and the findings of fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation are more commonly encountered in biopsies with extensive endocapillary proliferation. However, there are reported cases of LN in which focal segmental or diffuse glomerular necrosis or crescent formation occurs without significant subendothelial deposits (3–7). Schwartz et al. (3) described four cases of LN manifesting diffuse segmental or global endocapillary proliferation with only focal subendothelial deposits, two of which exhibited glomerular necrosis. These cases were reported before the advent of ANCA testing (3). Ferrario et al. (4) reported nine cases of focal and segmental LN, four of which were characterized by segmental glomerular necrosis without endocapillary hypercellularity. Immunofluorescence (IF) was performed in seven of the nine cases and either was negative or showed only mesangial positivity. Electron microscopy (EM) and ANCA testing were not performed. Akhtar et al. (5) and Charney et al. (6) each described two cases of LN with segmental glomerular necrosis and endocapillary hypercellularity, without subendothelial deposits. All four of the patients had negative ANCA serologies. Arahata et al. (7) described a single case of ANCA-associated necrotizing and crescentic GN in a patient with LN and scant subendothelial deposits.

A major modification introduced in the 2003 International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification of LN was to subdivide LN IV (endocapillary or extracapillary GN involving ≥50% of glomeruli) into LN IV-S and LN IV-G, on the basis of whether the glomerular lesions were segmental (S) or global (G) in distribution (1). This change in the classification scheme was based largely on the experience of the Lupus Nephritis Collaborative Study Group, which found that patients who meet criteria for IV-S have a worse outcome than those with IV-G (8). In this study, patients with LN IV-S had more extensive fibrinoid necrosis, a lesser degree of immune complex deposition, and a worse outcome, leading the authors to suggest that the findings resembled a “pauci-immune GN” (8). Two subsequent studies have confirmed that LN IV-S is associated with more extensive glomerular necrosis and less prominent subendothelial deposit formation than LN IV-G (9,10). In both of these studies, the authors raised the possibility that a pauci-immune mechanism may be playing a role in the cases of LN IV-S that exhibit prominent necrosis in the absence of significant endocapillary proliferation or subendothelial deposits (9,10). In the study by Hill et al. (9), ANCA was proposed as a potential pathomechanism, but the prevalence of ANCA seropositivity was not studied.

We previously reported three LN cases with extensive fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation, absent or rare subendothelial deposits, and positive ANCA serologies (11,12). In these cases, the disproportionate degree of necrosis and crescent formation suggested overlapping features of LN and ANCA-associated GN. In this report, we expand our experience to 10 cases. The clinical features, renal biopsy findings, and outcomes are provided.

Materials and Methods

We identified from the archives of the Renal Pathology Laboratory of Columbia University 10 renal biopsies showing LN that met the following criteria: (1) Prominent fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation, (2) minimal to absent subendothelial deposits, and (3) positive ANCA serologies. All patients met three or more American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (13). The 10 biopsies were received between 1994 and 2006.

All 10 renal biopsies were processed according to standard techniques for light microscopy (LM), IF, and EM. For each case, 11 glass slides were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, trichrome, and Jones methenamine silver. IF was performed on 3-μm cryostat sections using polyclonal FITC-conjugated antibodies to IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, κ, λ, fibrinogen, and albumin (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA). The intensity of IF staining was graded on a scale of 0 to 3+. Ultrastructural evaluation was performed using a JEOL 100S electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Patients’ medical charts were reviewed for demographics, clinical presentation, clinical and laboratory features of SLE and systemic vasculitis, ANCA titer and specificity, parameters of renal function, treatment, and outcome. The following clinical definitions were applied: Probable SLE, three ARA criteria; definite SLE, four ARA criteria; renal insufficiency, serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dl; nephrotic-range proteinuria, 24-h urine protein >3 g/d; hypoalbuminemia, serum albumin <3.5 g/dl; nephrotic syndrome, nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and peripheral edema; and hematuria, >5 red blood cells per high-power field on microscopic examination of the urinary sediment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Results

Clinical Features

The clinical features are summarized in Table 1. The cohort consisted of eight women and two men with a mean age of 48.4 yr (range 19 to 80 yr). Eight patients fulfilled four or more ARA criteria for SLE (definite SLE), and two patients (8 and 10) fulfilled three ARA criteria (probable SLE). Seven of the 10 patients had new onset of SLE. All patients had ANA positivity (titer range 1:40 to 1:2560), and nine had hypocomplementemia. Anti-DNA antibody was positive in four patients, borderline in one, and negative in five. All nine patients tested by indirect IF (IIF) had positive ANCA with a perinuclear staining pattern (P-ANCA). Serologic testing for ANCA by ELISA to determine the specificity of ANCA was performed in five patients, all of whom had antibodies against myeloperoxidase (MPO). Patients 4 and 8 had evidence of pulmonary hemorrhage; no additional extrarenal manifestations of vasculitis were identified in the remaining eight patients. Three patients had anti-histone antibody positivity and were receiving pharmacologic agents that have been associated with drug-induced SLE; patient 4 was receiving hydralazine 100 mg three times daily for 16 mo, patient 10 was taking hydralazine 100 mg twice daily for 18 mo, and patient 8 was on thioridazine for depression. The remaining seven patients were not receiving any medication that is known to cause drug-induced SLE or ANCA.

Table 1.

Clinical data

| Parameter | Patient

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Age (yr) | 22 | 37 | 62 | 80 | 19 | 50 | 55 | 37 | 44 | 78 |

| Race | White | Asian | African American | white | African American | white | white | African American | white | white |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female |

| ANA | Positive (1:1286) | Positive (1:80) | Positive (1:848) | Positive (1:2560) | Positive (1:160) | Positive (1:160) | Positive (1:160) | Positive (1:40) | Positive (1:320) | Positive (1:640) |

| Anti-DNA antibodies | Negative | Borderline | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| ARA criteria | +ANA, malar rash, pancytopenia, LN IV | +ANA, thromb-ocytopenia, arthritis, LN V | + ANA, + anti-DNA ab, anemia, LN III | +ANA, pleural effusion, pancytopenia, LN II | +ANA, +anti-DNA ab, anemia, LN IV | +ANA, pericarditis, malar rash, LN III | +ANA, +anti-DNA ab, pancytopenia, LN V | +ANA, pleuritic pain/pleural effusion, LN V | +ANA, +anti-DNA ab, pericarditis, arthralgias, LN III | +ANA, pleural effusion, LN III |

| Duration of SLE | New onset | New onset | 11 yr | New onset | New onset | 2.5 yr | New onset | 2 yr | New onset | New onset |

| ANCA by IIF | P-ANCA (1:160) | P-ANCA | P-ANCA (1:640) | P-ANCA (1:320) | P-ANCA (1:80) | P-ANCA | P-ANCA (1:160) | P-ANCA | P-ANCA | NA |

| ANCA specificity by ELISA | MPO (35, normal <21) | MPO (83.1, normal <15) | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | MPO (index 4.3, normal <1.0) | Not performed | MPO (55.5, normal <40) | Not performed | MPO (9.46), PR3 (1.26; normal <0.9) |

| Urine protein | 1.5 g/d | 5.9 g/d | 2 g/d | 4 + on UA | 4 + on UA | 3.2 g/d | 3 + on UA | 6.4 g/d | 1.7 g/d | 3 g/d |

| Hematuria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.4 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 2.2 | NA | 1.4 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| Serum creatinine baseline (mg/dl) | Normal | Normal | 0.8 | 1.6 | NA | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | Normal | 0.8 |

| Serum creatinine at biopsy (mg/dl) | 2.7 | 10 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 9.6 | 4.4 | 21 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.5 |

| Hypocomplementemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Edema | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes |

| Associated medical conditions | None | None | HTN | HTN, diabetes, right RAS, CAD | None | HTN, diabetes, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis | HTN, alcohol abuse, CVA, colon CA, urosepsis | HTN, diabetes | None | HTN |

| Treatment | Intravenous CY/PRED for 6 mo then MMF for 12 mo | Intravenous CY/PRED for 7 mo then azathioprine for 6 mo | Intravenous CY/PRED for 6 mo | D/C hydralazine, oral CY/PRED, PLX X3 | M-PRED for 3 d/one dose of intravenous CY then oral CY/PRED | M-PRED for 3 d then intravenous CY/PRED for 6 mo | Hemodialysis for 1 mo before biopsy, PRED for 10 d/one dose of intravenous CY | Intravenous CY/PRED for 4 mo, restarted intravenous CY/PRED for 3 mo for relapse 12 mo after biopsy | Intravenous CY/PRED for 12 mo then MMF for 12 mo then PRED/HC for 12 mo | D/C hydralazine one pulse of M-PRED then PRED for 6 mo/oral CY for 3 mo |

| Length of follow-up (mo) | 26 | 13 | 6 (died of pneumonia) | 1 (died of sepsis) | 3 | 14 | 1.5 (died of sepsis) | 15 | 36 | 17 |

| Follow-up creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 1.3 | NA | 0.9 at 4 mo 1.3-1.4 at 15 mo | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Follow-up proteinuria | Negative | Negative | 2 g/24 h at 3 mo | 4+ on UA | 1.7 | <200 mg/24 h | NA | 2.6/24 h | Negative | Negative |

| Follow-up hematuria | Negative | Negative | Negative | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | Negative | Negative |

| Follow-up ANCA | Negative | NA | NA | Positive P-ANCA (1:320) | Negative | Negative | NA | NA | Negative | Negative MPO and PR3 |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; ARA, American Rheumatism Association; CA, carcinoma; CAD, coronary artery disease; CY, cyclophosphamide; D/C, discontinued; HC, hydroxychloroquine; HTN, hypertension; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPO, myeloperoxidase; M-PRED, pulse methylprednisolone; NA, not available; PLX, plasmapheresis; PR3, proteinase 3; PRED, prednisone; RAS, renal artery stenosis; UA, urinalysis.

All patients had a nephritic presentation with hematuria and an abrupt rise in serum creatinine to a mean level of 7.1 mg/dl (range 1.1 to 21). Proteinuria also was documented in all patients, including two with full nephrotic syndrome. The mean 24-hr urine protein, available for seven patients, was 3.4 g/d (range 1.5 to 6.4 g). The remaining three patients had 3+ or 4+ proteinuria on urinalysis.

Pathologic Findings

The renal biopsy findings are detailed in Table 2. All biopsies exhibited necrotizing GN with fibrinoid necrosis, glomerular basement membrane rupture, and endocapillary and extracapillary fibrin. The necrotizing features involved a mean of 29% of glomeruli (range 14 to 50%). Crescents were present in nine of 10 cases and involved a mean of 31% of glomeruli (range 9 to 83%). All cases were interpreted as showing features of both ANCA-associated necrotizing and crescentic GN and LN.

Table 2.

Renal biopsy findings

| Finding | Patient

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Light microscopy | ||||||||||

| no. of glomeruli/no. of sclerotic glomeruli | 46/2 | 15/0 | 7/1 | 6/1 | 6/0 | 34/0 | 100/13 | 18/0 | 22/2 | 38/7 |

| mesangial proliferation | D&G | D&G | D&G | D&S | D&G | D&G | F&S | D&S | F&S | D&G |

| endocapillary proliferation | D&S | No | F&S | No | D&G | F&S | No | No | F&S | F&S |

| % of glomeruli with necrosis/crescents | 26/20 | 33/20 | 29/29 | 33/17 | 17/83 | 21/9 | 50/50 | 33/28 | 14/0 | 37/24 |

| wire-loop deposits | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis | Minimal | None | Mild | None | Mild | Minimal | Mild | None | None | Moderate |

| interstitial inflammation | Minimal | Moderate | Mild | Mild | Moderate | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Minimal | Moderate |

| vascular disease | No | Moderate | Moderate | No | Necrotizing vasculitis | Mild | Mild | No | No | Mild |

| Immunofluorescence | ||||||||||

| pattern in glomeruli | G MES and S GCW | G GCW | G MES and S GCW | G MES | G MES and S GCW | G MES and S GCW | G MES and G GCW | G MES and G GCW | G MES and S GCW | G MES and S GCW |

| positive immuno-reactants | 3+ IgG, 2+ IgM, 1+ IgA, 3+ C3, 2+ C1q | 3+ IgG, 3+ C3, 1+ C1q | 1+ IgG, 1+ IgM, 2+ C3 | 1+ IgG, 1+ IgM, ±C3 | 3+ IgG, 1+ IgA, 2+ C3, 1+ C1q | 3+ IgG, ±IgM, 1+ IgA, 2+ C3, 2+ C1q | 2+ IgG, 2+ C3 | 3+ IgG, 2+ C3 | 2+ IgG, 1+ IgM, 1+ IgA, 2+ C3 | 2 + IgG, ±IgM, 2+ C3 |

| interstitial or TBM deposits | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| vascular deposits | 2+ IgG | 3+ IgG | No | No | 2+ IgG | 2+ IgG | No | No | 1+ IgG | No |

| Electron microscopy | ||||||||||

| mesangial deposits | G | S | S | G | G | G | G | G | G | G |

| subendothelial deposits | Rare | No | Rare | No | S | Rare | No | No | No | No |

| subepithelial deposits | Rare | G | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare | G | G | No | No |

| TBM or BC deposits | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| endothelial TRI | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| % foot process effacement | 40 | 95 | 80 | 70 | 85 | 10 | 95 | 90 | 25 | 70 |

| Final diagnosis | LN IV-S (A/C)/ANCA GN | LN V/ANCA GN | LN III (A/C)/ANCA GN | LN II/ANCA GN | LN IV-G (A)/ANCA vasculitis | LN III (A)/ANCA GN | LN V/ANCA GN | LN V/ANCA GN | LN III (A/C)/ANCA GN | LN III (A/C)/ANCA GN |

BC, Bowman's capsule; GCW, glomerular capillary wall; D, diffuse; F, focal; G, global; MES, mesangial; S, segmental; TBM, tubular basement membranes; TRI, tubuloreticular inclusions.

Patient 4 exhibited necrosis and crescent formation with only mesangial proliferation and mesangial deposits. No endocapillary proliferation or subendothelial deposits were seen. The findings were interpreted as ANCA-associated GN and LN II, rather than solely LN III.

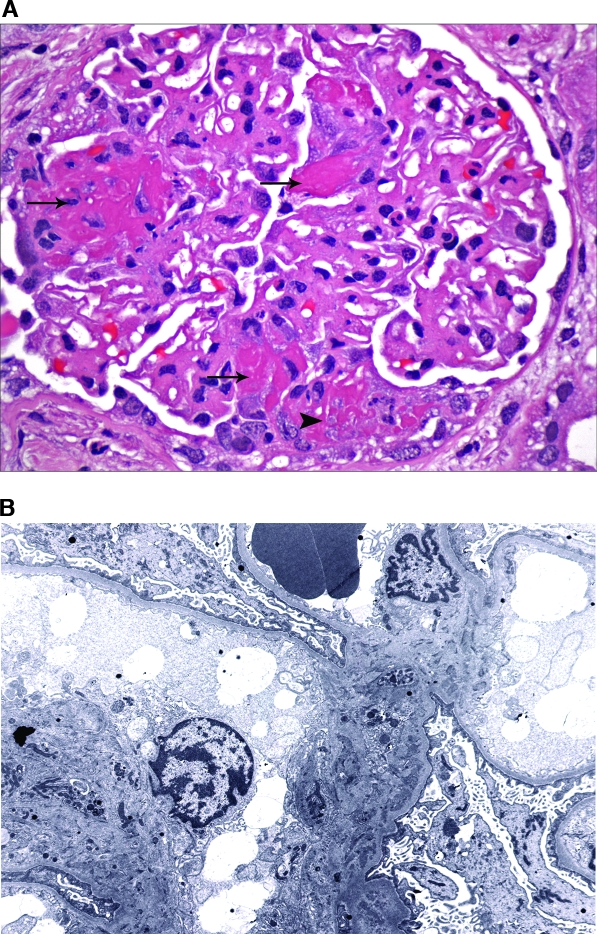

In patients 3, 6, 9, and 10, endocapillary proliferation was focal (involving <50% of glomeruli) and segmental (involving <50% of the glomerular tuft; Figure 1A). IF revealed global mesangial and segmental capillary wall positivity. EM disclosed mesangial electron-dense deposits (all four patients; Figure 1B) and endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions (patients 3, 6, and 9). Subendothelial deposits ranged from rare (patients 3 and 6) to absent (patients 9 and 10). In light of the prominent fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation but only rare or absent subendothelial deposits, the findings were interpreted as LN III and ANCA-associated GN.

Figure 1.

Lupus nephritis (LN) III with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. (A) A glomerulus from patient 10 exhibits three separate foci of fibrinoid necrosis (arrows), one of which is associated with a segmental small cellular crescent (arrowhead). Mild global mesangial proliferation and expansion are seen. (B) Ultrastructural evaluation reveals solely mesangial electron-dense deposits. No subendothelial or subepithelial deposits were identified. Magnifications: ×600 in A (hematoxylin and eosin); ×3000 in B.

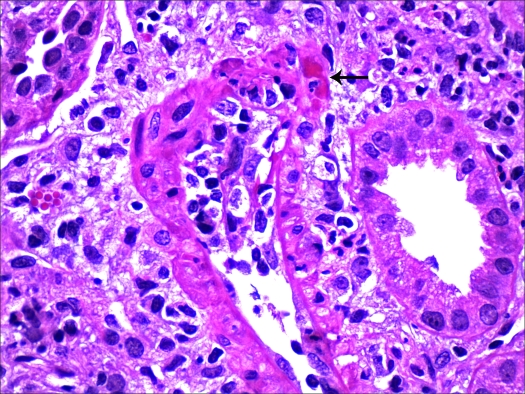

Patient 1 exhibited diffuse segmental endocapillary proliferative GN with necrotizing features and cellular crescents. IF revealed “full house” staining for Ig and complement in a mesangial and segmental glomerular capillary wall distribution, and EM revealed global mesangial but only rare segmental subendothelial deposits. The findings were diagnostic of LN IV-S. Although disproportionate necrosis and crescent formation with only rare subendothelial deposits can be seen in LN IV-S (8–10), the clinical history was notable for MPO-ANCA seropositivity. Thus, we favored an interpretation of LN IV-S with coexistent ANCA-associated GN. Patient 5 displayed diffuse and global endocapillary proliferation consistent with LN IV-G. Cellular crescents were present in five of six glomeruli sampled. EM revealed global mesangial and segmental subendothelial deposits. The findings were notable for multifocal necrotizing vasculitis with transmural infiltration by neutrophils and monocytes, fibrinoid necrosis, and rupture of the elastica interna (Figure 2). The pattern of necrotizing vasculitis was typical of ANCA-associated vasculitis and unusual for LN. As a result, ANCA positivity was thought to be playing a role in the vasculitis and possibly the glomerular necrosis and crescent formation.

Figure 2.

Necrotizing vasculitis. An interlobular artery from patient 5 exhibits dense intimal and focal transmural inflammation with medial fibrinoid necrosis (arrow). Magnification, ×600 (hematoxylin and eosin).

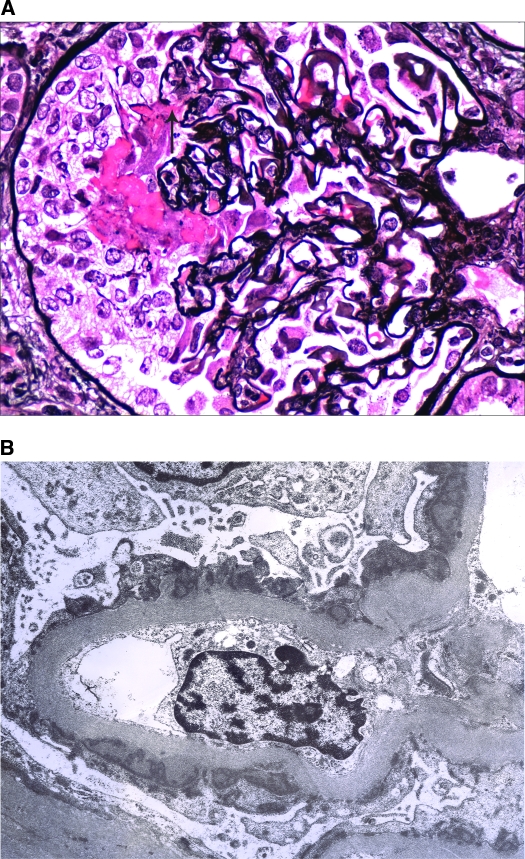

Patients 2, 7, and 8 displayed features of membranous LN (LN V) with global subepithelial deposits and intervening spikes. The changes were accompanied by mild mesangial hypercellularity, prominent necrosis and crescent formation, and the absence of endocapillary proliferation or subendothelial deposits (Figure 3). The findings of prominent fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation were interpreted as manifestations of ANCA-associated GN, coexisting with LN V.

Figure 3.

LN V with ANCA-associated necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. (A) A glomerulus from patient 2 exhibits segmental fibrinoid necrosis, rupture of the glomerular basement membrane (arrow), and an overlying cellular crescent. There is also mild thickening of the glomerular basement membrane. (B) Ultrastructural evaluation reveals global subepithelial electron-dense deposits with focal small intervening spikes. No subendothelial deposits were identified. Magnifications: ×600 in A (Jones methenamine silver); ×6000 in B.

Endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions, a characteristic feature of LN, were seen in nine of 10 biopsies. Large subendothelial “wire-loop” deposits were not seen in any case. Extraglomerular deposits were seen by IF or EM in seven cases, including five with vessel wall deposits. No features of diabetic glomerulosclerosis were seen in the three patients with a history of diabetes (patients 4, 6, and 8).

Clinical Outcome

The mean duration of follow-up was 13.3 mo (range 1 to 36 mo). In light of the necrotizing features, prominent crescent formation, and ANCA seropositivity, all patients were treated with cyclophosphamide. Seven patients were initially treated with intravenous monthly cyclophosphamide and oral prednisone for varying lengths of time (range 1 to 12 mo). This was followed by azathioprine for 6 mo in patient 2, mycophenolate mofetil for 12 mo in patient 1, and mycophenolate mofetil for 12 mo followed by oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine for 12 mo in patient 9. All three patients had excellent outcomes. After 3 d of pulse methylprednisolone and a single dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide, patient 5 was switched to oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Patient 7 was on hemodialysis for 1 mo before biopsy, received oral prednisone and a single dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide, and died with sepsis 1.5 mo into treatment. Intravenous cyclophosphamide and oral prednisone led to at least initial clinical improvement in patients 3, 6, and 8. Hydralazine was discontinued in patient 4, and she was treated with oral prednisone, oral cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis. She died of Gram-negative sepsis 1 mo after biopsy, at which time her creatinine had declined from 4.5 to 2.4 mg/dl. Hydralazine also was discontinued in patient 10. At 17 mo of follow-up, after oral cyclophosphamide for 3 mo and oral prednisone for 6 mo, her creatinine declined from 4.5 to 1.1 mg/dl.

Eight of nine patients with available follow-up had improvement in renal function. Four patients had complete resolution of hematuria, proteinuria, and renal dysfunction (patients 1, 2, 9, and 10). Four additional patients (patients 3, 4, 6, and 8) had partial recovery with a decrease in serum creatinine, with or without disappearance of hematuria and proteinuria. Patient 5 had necrotizing vasculitis on biopsy, was treated with intravenous followed by oral cyclophosphamide plus prednisone, and remained dialysis dependent 3 mo into treatment.

ANCA testing was repeated after treatment in six patients, five of whom became ANCA negative. In the single remaining patient (patient 4), ANCA titer remained unchanged at 1 mo, at which time the patient died. Repeat ANA titers were not available.

Discussion

ANCA are directed against cytoplasmic constituents of neutrophils and monocytes. ANCA testing is performed by IIF on alcohol-fixed human neutrophils, whereby two staining patterns are observed, cytoplasmic (c-ANCA) and perinuclear (p-ANCA). The specific ANCA target antigens can be determined by ELISA. The target antigen for c-ANCA is usually PR3. The target antigen for p-ANCA is most commonly MPO, although less frequent antigens seen mainly in patients with SLE include lactoferrin (LF), cathepsin G, lysozyme, elastase, and others. MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA are directly implicated in the pathogenesis of pauci-immune crescentic GN and pauci-immune small-vessel vasculitis, and ANCA seropositivity is found in the majority of patients with these conditions.

Approximately 20% of patients with SLE have ANCA positivity by IIF, mainly with a p-ANCA pattern (14). ANCA seropositivity by ELISA is less frequent, and the target antigens are most commonly LF, cathepsin G, and MPO (14). A study on 566 patients with SLE from multiple centers in Europe found ANCA positivity by IIF in 16.4% of patients, including 15.4% p-ANCA and 1% c-ANCA (15). By ELISA, 9.3% had MPO-ANCA positivity, and 1.7% had PR3-ANCA positivity. Antibodies against LF and lysozyme were present in 14.3 and 4.6% of patients, respectively (15). As shown in both of these studies, ANCA positivity by IIF in patients with SLE is greater than by ELISA. This is due to the presence of non-PR3, non-MPO ANCA as well as the difficulty in distinguishing p-ANCA from ANA by IIF. Confirmation of positive IIF results with ELISA is recommended for patients with SLE.

There are conflicting reports on the significance of ANCA positivity in patients with SLE (14,16–19). Lee et al. (16) studied 79 patients in Hong Kong and found a correlation between LF-ANCA positivity and SLE disease duration, clinical flare, and lymphadenopathy. Chin et al. (17) examined 51 patients in South Korea with LN and found ANCA positivity by IIF in 37.3% of patients, including p-ANCA in 31.4% and c-ANCA in 5.9%. The target antigen by ELISA was LF-ANCA in 25% of patients and MPO-ANCA in 2%. ANCA seropositivity was associated with the presence of nephritis, particularly LN IV, as well as anti-dsDNA antibodies (17). Other reports have failed to show a correlation between ANCA and clinical features or organ involvement (14,18,19).

Herein we describe 10 cases of LN in which the renal biopsy findings of prominent necrosis, cellular crescents, and in a single case necrotizing vasculitis raised the possibility of coexistent ANCA-associated GN. In each case, ANCA testing was performed and positive results were obtained. Because of the presence of no more than rare, segmental subendothelial deposits, we believe that these cases represent an overlap of LN and ANCA-associated GN. All nine patients tested by IIF were found to have p-ANCA positivity. Five patients were tested by ELISA and had positivity for MPO-ANCA. Although it is unfortunate that ELISA testing was not performed for five patients, it is noteworthy that all of the four patients with a positive p-ANCA by IIF had MPO-ANCA by ELISA. Testing for less common ANCA target antigens, such as LF and cathepsin G, was not performed. From the standpoint of SLE, the biopsy findings were interpreted as LN II (one case), LN III (four cases), LN IV-S (one case), LN IV-G (one case), and LN V (three cases; Table 2). Had ANCA testing not been performed, the necrotizing features and crescent formation likely would have led to an incorrect diagnosis of LN III or IV in all of the cases. In the three patients with LN V and the single patient with LN II, the complete absence of subendothelial deposits favored the interpretation that the glomerular necrosis and crescent formation were related to ANCA seropositivity. In the remaining six cases, all of which were classified as LN III or LN IV, the necrosis and crescent formation could be interpreted as manifestations of LN, although the rarity or absence of subendothelial deposits suggested coexistent ANCA-associated GN. Similarly, the necrotizing vasculitis seen in patient 5 was more typical of ANCA-associated disease.

Drug-induced SLE develops in 7 to 20% of patients who are treated with hydralazine (20). This serious adverse effect is dose dependent and typically affects patients who receive a dosage of at least 100 mg/d. Ihle et al. (21) reported six patients who had hypertension and developed LN after receiving hydralazine for 6 mo to 7 yr. All six patients had a positive ANA, four had positive anti-DNA antibody, and three had hypocomplementemia. Discontinuation of hydralazine together with immunosuppressive therapy led to improvement of renal function. Treatment with hydralazine is also associated with ANCA-associated necrotizing and crescentic GN, often with coexistent ANA positivity (22,23). Two of the cases reported herein (patients 4 and 10) were being treated with hydralazine and had positive anti-histone antibodies, a marker of drug-induced SLE. It is likely that hydralazine played a role in the development of LN and ANCA-associated GN in these patients. Of note, patient 8 was being treated for depression with thioridazine, which has been associated rarely with ANCA-positive vasculitis and an SLE-like syndrome (24,25).

Although LN is generally regarded as a classic immune complex GN, several investigators have suggested that the subgroup of LN IV-S and LN III with extensive segmental necrosis and crescent formation may have a different pathogenesis (3,4,8–10). These reports have raised the possibility of a mechanism akin to pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic GN, but ANCA testing was not performed in any of these series. Our cohort strongly supports a pathogenetic role for ANCA in a small group of patients with SLE. Furthermore, our findings suggest that ANCA testing, preferably by ELISA, should be performed in all patients who have SLE and in whom renal biopsy reveals extensive necrosis and crescent formation in the absence of significant endocapillary proliferation or subendothelial deposits. Because this constellation of findings is most commonly encountered in LN IV-S (8–10), future studies that systematically test for ANCA by ELISA in patients with LN IV-S are needed. In the absence of ANCA testing, we likely would have incorrectly classified our four cases of LN II and LN V as LN III or IV-S.

All 10 patients in our cohort were treated with cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Seven patients received intravenous cyclophosphamide, two received oral cyclophosphamide, and one received a single dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral cyclophosphamide. Intravenous cyclophosphamide is more commonly used to treat crescentic LN, whereas oral cyclophosphamide is more commonly used in ANCA-associated GN. Three patients died as result of pneumonia or sepsis within 6 mo of renal biopsy, although comorbid conditions likely were contributing factors. Among the remaining seven patients, five had a complete or near-complete remission (patients 1, 2, 6, 9, and 10), one had a remission with subsequent relapse (patient 8), and one who had LN IV-G and necrotizing vasculitis on renal biopsy had no significant response to therapy (patient 5). It is difficult to draw conclusions on treatment from our small cohort. The 30% mortality rate within 6 mo of biopsy is disturbing, although multiple factors likely played a role. In the remaining seven patients, the excellent clinical outcome in six of seven patients suggests that aggressive therapy with intravenous or oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone is warranted. The relative benefit of intravenous versus oral cyclophosphamide cannot be evaluated from our data.

The high incidence of ANCA seropositivity, particularly MPO-ANCA, in patients with SLE raises the possibility that the findings in our cohort may represent more than the coincidental occurrence of two unrelated diseases. It is possible that one of the two conditions may be creating fertile conditions for the second to develop. For instance, SLE and LN may be facilitating the process of MPO autoantibody formation by promoting neutrophil degranulation and priming neutrophils to increase surface expression of MPO. ANCA may be one of many possible autoantibodies occurring in SLE. Of note, coexistent ANCA-associated GN has also been described in patients with IgA nephropathy (26).

There are multiple limitations to the findings in the report. We did not systematically study ANCA serologies in all patients with LN, and we did not exclude the possibility of SLE in all patients with ANCA-associated pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic GN. Therefore, we cannot address the incidence of the coexistence of the two disease processes. Another important limitation of this report is the absence of ELISA testing for MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA in five of the 10 patients, although it is notable that MPO-ANCA were identified in all five patients who were studied. We strongly recommend using ELISA to confirm positive ANCA by IIF in all patients with SLE. Despite these limitations, it is our hope that this small series will raise awareness of the potential overlap of biopsy findings of LN and ANCA-associated disease and will encourage more systematic ANCA testing in patients with LN.

Conclusions

We report 10 cases LN in which the degree of necrosis and crescent formation significantly exceeded that of endocapillary proliferation or subendothelial deposit formation. All 10 patients had ANCA positivity, suggesting that these cases represent the coexistence of LN and ANCA-associated necrotizing and crescentic GN. In the setting of LN with ANCA-associated GN, aggressive immunosuppressive therapy appears warranted.

Disclosures

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Weening JJ, D'Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M: The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. Kidney Int 65: 521–530, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennette JC, Xiao H, Falk RJ: Pathogenesis of vascular inflammation by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1235–1242, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz MM, Roberts JL, Lewis EJ: Necrotizing glomerulitis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Pathol 14: 158–167, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrario F, Napodano P, Giordano A, Gandini E, Boeri R, D'Amico G: Peculiar type of focal and segmental lupus glomerulitis: Glomerulonephritis or vasculitis? Contrib Nephrol 99: 86–93, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhtar M, al-Dalaan A, el-Ramahi KM: Pauci-immune necrotizing lupus nephritis: Report of two cases. Am J Kidney Dis 23: 320–325, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charney DA, Nassar G, Truong L, Nadasdy T: “Pauci-Immune” proliferative and necrotizing glomerulonephritis with thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus-like syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 1193–1206, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arahata H, Migita K, Izumoto H, Miyashita T, Munakata H, Nakamura H, Tominaga M, Origuchi T, Kawabe Y, Hida A, Taguchi T, Eguchi K: Successful treatment of rapidly progressive lupus nephritis associated with anti-MPO antibodies by intravenous immunoglobulins. Clin Rheumatol 18: 77–81, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Najafi CC, Korbet SM, Lewis EJ, Schwartz MM, Reichlin M, Evans J, Lupus Nephritis Collaborative Study Group: Significance of histologic patterns of glomerular injury upon long-term prognosis in severe lupus glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 59: 2156–2163, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D, Bariety J: Class IV-S versus class IV-G lupus nephritis: Clinical and morphologic differences suggesting different pathogenesis. Kidney Int 68: 2288–2297, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittal B, Hurwitz S, Rennke H, Singh AK: New subcategories of class IV lupus nephritis: Are there clinical, histologic, and outcome differences? Am J Kidney Dis 44: 1050–1059, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masani NN, Imbriano LJ, D'Agati VD, Markowitz GS: SLE and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 950–955, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall S, Dressler R, D'Agati V: Membranous lupus nephritis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated segmental necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 119–124, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ: The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 25: 1271–1277, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen D, Isenberg DA: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 12: 651–658, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galeazzi M, Morozzi G, Sebastiani GD, Bellisai F, Marcolongo R, Cervera R, De Ramòn Garrido E, Fernandez-Nebro A, Houssiau F, Jedryka-Goral A, Mathieu A, Papasteriades C, Piette JC, Scorza R, Smolen J: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in 566 European patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence, clinical associations and correlation with other autoantibodies. European Concerted Action on the Immunogenetics of SLE. Clin Exp Rheumatol 16: 541–546, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SS, Lawton JW, Chan CE, Li CS, Kwan TH, Chau KF: Antilactoferrin antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol 31: 669–673, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin HJ, Ahn C, Lim CS, Chung HK, Lee JG, Song YW, Lee HS, Han JS, Kim S, Lee JS: Clinical implications of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test in lupus nephritis. Am J Nephrol 20: 57–63, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauzner R, Urowitz M, Gladman D, Gough J: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 21: 1670–1673, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishiya K, Chikazawa H, Nishimura S, Hisakawa N, Hashimoto K: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus is unrelated to clinical features. Clin Rheumatol 16: 70–75, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finks SW, Finks AL, Self TH: Hydralazine-induced lupus: Maintaining vigilance with increased use in patients with heart failure. South Med J 99: 18–22, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ihle BU, Whitworth JA, Dowling JP, Kincaid-Smith P: Hydralazine and lupus nephritis. Clin Nephrol 22: 230–238, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi HK, Merkel PA, Walker AM, Niles JL: Drug-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis: Prevalence among patients with high titers of antimyeloperoxidase antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 43: 405–413, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torffvit O, Thysell H, Nassberger L: Occurrence of autoantibodies directed against myeloperoxidase and elastase in patients treated with hydralazine and presenting with glomerulonephritis. Hum Exp Toxicol 13: 563–567, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenfield JR, McGrath M, Kossard S, Charlesworth JA, Campbell LV: ANCA-positive vasculitis induced by thioridazine: Confirmed by rechallenge. Br J Dermatol 147: 1265–1267, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Physician's Desk Reference, 61st Ed., Montvale, NJ, Thomson PDR, 2007, p 2165

- 26.Haas M, Jafri J, Bartosh SM, Karp SL, Adler SG, Meehan SM: ANCA-associated crescentic glomerulonephritis with mesangial IgA deposits. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 709–718, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]