Abstract

The molecular mechanisms of acute kidney injury (AKI) remain unclear. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), widely expressed on leukocytes and kidney epithelial cells, regulate innate and adaptive immune responses. The present study examined the role of TLR signaling in cisplatin-induced AKI. Cisplatin-treated wild-type mice had significantly more renal dysfunction, histologic damage, and leukocytes infiltrating the kidney than similarly treated mice with a targeted deletion of TLR4 [Tlr4(−/−)]. Levels of cytokines in serum, kidney, and urine were increased significantly in cisplatin-treated wild-type mice compared with saline-treated wild-type mice and cisplatin-treated Tlr4(−/−) mice. Activation of JNK and p38, which was associated with cisplatin-induced renal injury in wild-type mice, was significantly blunted in Tlr4(−/−) mice. Using bone marrow chimeric mice, it was determined that renal parenchymal TLR4, rather than myeloid TLR4, mediated the nephrotoxic effects of cisplatin. Therefore, activation of TLR4 on renal parenchymal cells may activate p38 MAPK pathways, leading to increased production of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and subsequent kidney injury. Targeting the TLR4 signaling pathways may be a feasible therapeutic strategy to prevent cisplatin-induced AKI in humans.

A major toxicity of the cancer chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin is acute renal failure.1 In previous animal studies, we and others have demonstrated an important role for TNF-α in the pathogenesis of cisplatin-induced renal injury.2–6 Inhibition of TNF-α production or action markedly reduced the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin.2,3 Stimulation of TNF-α production in the kidney by cisplatin involved both a stabilization of TNF-α mRNA7 and a p38 MAPK-dependent increase in TNF-α mRNA translation,4 however, the upstream signals responsible for TNF-α production remain unclear.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of receptors positioned as a first line of innate defense by recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns as well as endogenous signals of tissue injury.8,9 TLRs are differentially expressed on leukocyte subsets and nonimmune cells and regulate important aspects of innate and adaptive immune responses. Upon stimulation, TLRs induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines or costimulatory molecules via MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent signaling pathways.9,10 Within the kidney, tubular epithelial cells express TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR6, suggesting that these TLRs might contribute to the activation of immune responses in tubulointerstitial injury.11–13

The most extensively characterized Toll-like receptor, TLR4, is the receptor for the endotoxin of gram-negative bacteria.14,15 Previous studies by Cunningham et al.16 demonstrated that endotoxin-induced acute renal failure is completely dependent on TLR4 signaling. Likewise, we recently demonstrated that cisplatin and endotoxin exert synergistic renal toxicity that is TLR4-dependent.17 In addition to bacterial endotoxin, TLR4 can also be activated by endogenous molecules or “danger signals” released during tissue injury.18,19 TLR4 activation, presumably by these danger signals, has been implicated in ischemic injury to both the liver and the heart.20,21 These observations raised the interesting possibility that TLR4 activation may be responsible for initiating cytokine production and renal dysfunction during cisplatin nephrotoxicity. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of cisplatin in wild-type and TLR4-deficient mice with particular attention to functional and histologic kidney damage, leukocyte infiltration, and cytokine production. We also created bone marrow chimeric mice to investigate the site at which TLR4 exerts its effects in this model of acute kidney injury. Our results establish that TLR4 expressed on renal parenchymal cells is an important mediator of cisplatin-induced cytokine production, inflammation, and renal injury.

RESULTS

TLR4 Contributes to Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity

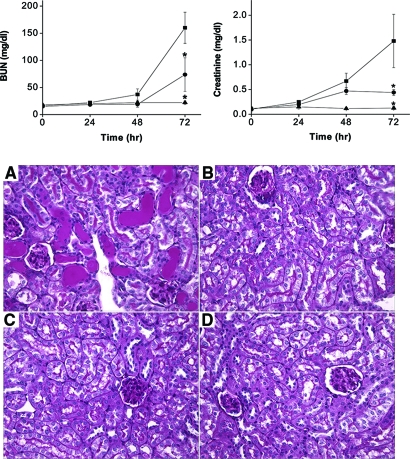

To determine if TLR4 participates in the pathogenesis of cisplatin nephrotoxicity, wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice were treated with toxic doses of cisplatin. Renal function was monitored over the ensuing 72 h using blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine as indices of function. As shown in Figure 1, wild-type mice developed severe renal failure between 48 and 72 h after cisplatin injection. By comparison, Tlr4-deficient mice had significantly better renal function. The better preservation of renal function in the Tlr4-deficient mice was also reflected histologically. Thus, 72 h after cisplatin treatment, kidneys of wild-type mice showed severe tubular injury as evidenced by cast formation, loss of brush border membranes, sloughing of tubular epithelial cells, and dilation of tubules (Figure 1). These changes were minimal in kidneys from Tlr4-deficient mice. Semiquantitative assessment of histologic injury yielded tubular necrosis scores of 3.3 ± 0.3 in cisplatin-treated wild-type mice and 1.6 ± 0.2 in TLR4-deficient mice (P < 0.002, n = 6). These results indicate that TLR4 signaling contributes to both the structural and functional consequences of cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Deletion of Tlr4 also provided protection against renal dysfunction induced by 30 min of bilateral renal ischemia (Supplemental data).

Figure 1.

Dependence of cisplatin nephrotoxicity on TLR4. (Top) Effect of cisplatin on renal function in C57BL/6 (▪) or Tlr4(−/−) (•) mice. Male mice were injected with saline (▴) or 20 mg/kg cisplatin (▪, •). Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine were measured at the indicated time points. *P < 0.05 versus C57BL/6 cisplatin-injected mice; n = 4 to 7. (Bottom) Effect of cisplatin on kidney morphology in C57BL/6 (A and C) and Tlr4(−/−) mice (B and D). Kidneys were removed 72 h after injection with cisplatin (A and B) or saline (C and D). Sections were stained with PAS (original magnification ×40). Wild-type mice exhibit severe tubular necrosis, tubular dilation, and cast formation throughout the cortex. Tlr4(−/−) mice have relatively well-preserved renal morphology.

TLR4 Mediates Leukocyte Infiltration and Cytokine Production in Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity

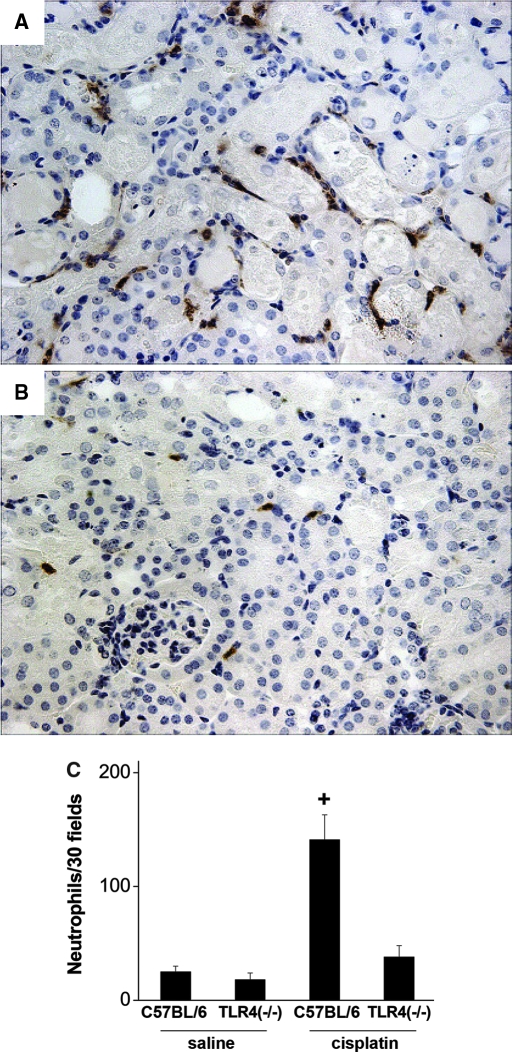

We have previously documented the infiltration of leukocytes into the kidneys during cisplatin toxicity.2,3,22 To determine if TLR4 signaling mediates this process, kidney sections from the cisplatin-treated wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice were stained for neutrophils. As seen in Figure 2, the wild-type mice displayed severe tubular injury and a robust infiltration of neutrophils. In contrast, Tlr4-deficient mice had significantly fewer infiltrating neutrophils, similar to levels seen in kidneys from saline treated mice. These results suggest that one of the mechanisms whereby TLR4 may induce renal injury is through promotion of an inflammatory response involving leukocytes.

Figure 2.

Neutrophil infiltration in cisplatin nephrotoxicity requires the presence of TLR4. Sections of kidney harvested from C57BL/6 (A) or Tlr4(−/−) (B) mice 72 h after cisplatin injection were stained for neutrophils as described in “Concise Methods.” (C) Thirty ×40 fields of kidney cortex were examined from each animal. The total number of neutrophils in those 30 fields is presented. +P < 0.01 versus all others; n = 3 to 7.

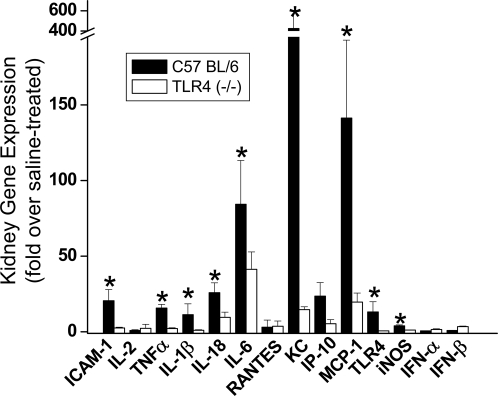

The expression of a number of chemokines and cytokines is increased in kidneys of cisplatin-treated mice and contribute to the renal injury.2,3,22 Because TLR4 activation leads to the production of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, including TNF-α, we sought to determine whether TLR4 mediates cisplatin-induced chemokine and cytokine production. Gene expression in kidney tissue was analyzed by real-time reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Figure 3). The results indicate that, as reported previously,2,3,22 a number of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules are upregulated in the kidney after cisplatin administration. Importantly, the upregulation of many of these genes, such as ICAM-1, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-18, IP-10, KC, and MCP-1, was TLR4-dependent. The expression of iNOS was increased in a TLR4-dependent manner, whereas IFN-α and IFN-β were not upregulated in response to cisplatin.

Figure 3.

Dependence of renal gene expression on the presence of TLR4. Kidney mRNA abundance of ICAM-1, various cytokines and chemokines, TLR4, and iNOS were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Expression levels are shown as relative fold changes compared with saline-treated mice of the same genotype. *P < 0.05 versus Tlr4(−/−); n = 3.

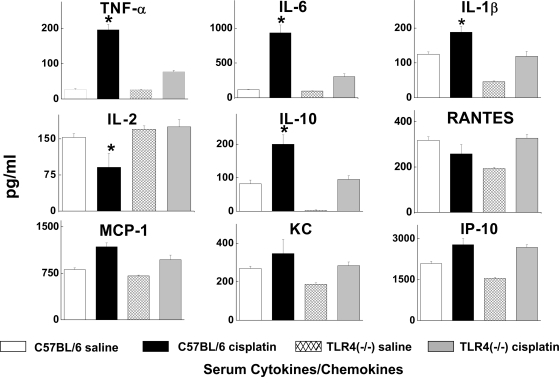

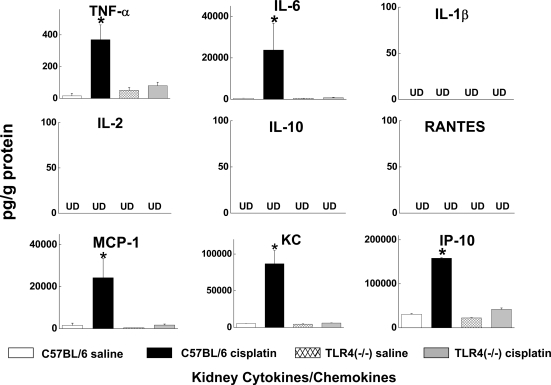

We also used a bead-based multiplex immunoassay to measure the levels of 9 chemokines and cytokines in serum, kidney, and urine of wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice treated with saline or cisplatin. Consistent with our prior findings,2,3,22 serum TNF-α concentrations were increased by cisplatin. However, TNF-α levels in the cisplatin-treated Tlr4-deficient mice were significantly lower. Likewise, serum levels of IL-6, IL-10, and IL-1β were all lower in cisplatin-treated Tlr4-deficient mice compared with wild-type mice (Figure 4). Measurement of cytokine and chemokine levels in kidney homogenates (Figure 5) demonstrated significant increases in TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, KC, and IP-10 in cisplatin-treated wild-type mice. These changes were completely absent in Tlr4-deficient mice.

Figure 4.

Effects of cisplatin on the serum cytokine expression profile. Serum cytokine levels were measured using a bead-based multiplexed cytokine analysis system. Samples were obtained from C57BL/6 or Tlr4(−/−) mice 72 h after saline or cisplatin injection. *P < 0.05, C57BL/6 versus TLR4(−/−); n = 3 to 5.

Figure 5.

Effects of cisplatin on kidney cytokine levels. Kidneys were obtained from C57BL/6 or Tlr4(−/−) mice 72 h after saline or cisplatin injection. *P < 0.05 C57BL/6 versus Tlr4(−/−); n = 3 to 5. UD, undetectable.

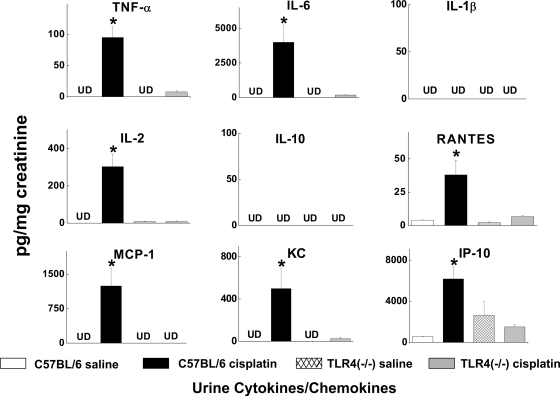

Measurement of chemokines and cytokines in the urine might provide a noninvasive view of the inflammatory milieu within the kidney. The levels of most of the measured chemokines and cytokines were undetectable in urine from saline treated mice. However, cisplatin caused a dramatic increase in the urine concentrations of several chemokines and cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6, MCP-1, IP-10, RANTES, and KC (Figure 6). Deletion of TLR4 completely abrogated these responses to cisplatin. Indeed, the urinary levels of cytokines closely reflected the levels measured in kidney homogenates. Taken together, these results indicate that TLR4 signaling is responsible for the production of several potent proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in response to cisplatin. The suppression of MCP-1, RANTES, and KC in the Tlr4-deficient mice may account for the decrease in infiltrating leukocytes noted above (Figure 2).

Figure 6.

Effects of cisplatin on urine cytokine excretion. Urine samples were obtained from C57BL/6 or Tlr4(−/−) mice 72 h after saline or cisplatin. Cytokine levels were normalized to the creatinine concentration in the urine. *P < 0.05 C57BL/6 versus Tlr4(−/−); n = 3 to 5. UD, undetectable.

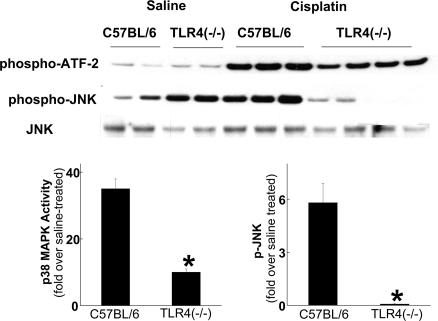

Cisplatin-mediated MAPK Activation is TLR4-dependent

JNK and p38 MAPK are downstream mediators of TLR4 signaling.9 Moreover, JNK and p38 MAPK activation have been associated with tissue injury in a variety of organs, including the kidney.23–25 We have shown that cisplatin stimulates both JNK and p38 MAPK activity in renal tubular epithelial cells and that cisplatin-induced TNF-α production by renal epithelial cells is p38 MAPK-dependent.4 Therefore, we wished to determine whether the cisplatin-induced activation of JNK and p38 MAPK in the kidney is mediated through TLR4. Immunokinase and Western blot analysis was performed on kidneys from wild-type and TLR4-deficient mice. As shown in Figure 7, cisplatin activated p38 MAPK and JNK in wild-type mice. The activity of p38 MAPK was modestly lower, and p-JNK dramatically lower, in kidneys from TLR4-deficient mice. These results are consistent with the view that the majority of JNK activation and a portion of p38 MAPK activation in response to cisplatin result from TLR4 activation.

Figure 7.

Effects of cisplatin treatment on p38 MAPK activity and JNK phosphorylation. Kidneys were removed from C57BL/6 or Tlr4(−/−) mice 72 h after injection with either saline or cisplatin and homogenized. p38 MAPK activity was determined by immunoprecipitation and phosphorylation of ATF-2, and JNK phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis. Densitometry of results from two independent experiments is shown below the blots. *P < 0.05 versus C57BL/6.

A number of endogenous ligands for TLR4 have been reported.18,19 We measured the renal expression of several of these ligands and determined the effect of cisplatin on their expression (Figure S2). Cisplatin increased the expression of gp96, an ER chaperone that also activates TLR4.26 The increase in gp96 was not seen in cisplatin-treated Trl4-deficient mice. Cisplatin had no effect on the expression of several other TLR4 ligands, such as HSP60, HSP70, HMGB1, and β-defensin 2.

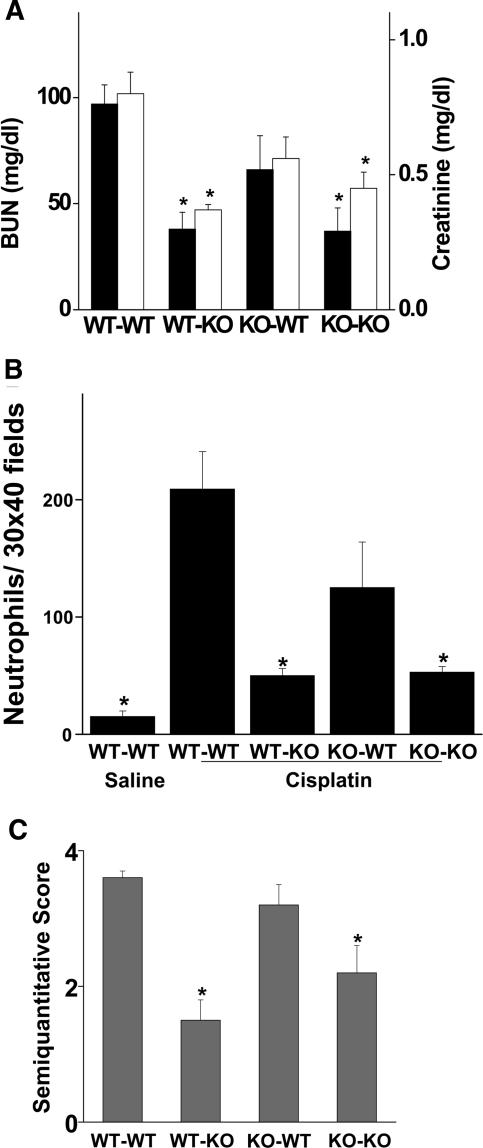

Role of Renal and Myeloid TLR4 in Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity

TLR4 is expressed on a variety of cells, including circulating and resident immune cells and renal epithelial cells. Activation of TLR4 at any of these sites could lead to renal injury. To define the location of the TLR4 that mediates cisplatin nephrotoxicity, chimeric mice were created in which either myeloid cells or kidney parenchymal cells lacked TLR4 receptors. These mice were then treated with cisplatin, and renal function was assessed. As shown in Figure 8, WT→WT chimeras developed acute renal failure after cisplatin injection, whereas KO→KO chimeras had relatively little renal dysfunction. These results are similar to what was observed in wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice (Figure 1), indicating that the process of producing chimeric mice did not alter the susceptibility to cisplatin or the dependence upon TLR4. Of note, the KO→WT chimeras (i.e., mice lacking myeloid TLR4) developed renal failure. In contrast, WT→KO chimeras, which lacked renal parenchymal TLR4, were resistant to cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Similarly, cisplatin produced a marked increase in neutrophil content in kidneys of WT→WT and KO→WT mice but not in WT→KO or KO→KO mice (Figure 8B). Finally, an assessment of histologic injury (Figure 8C) paralleled the functional data. That is, WT→WT and KO→WT mice had significantly greater injury scores (3.6 ± 0.1 and 3.2 ± 0.3) than either WT→KO or KO→KO mice (1.5 ± 0.3 and 2.2 ± 0.4, respectively, P < 0.01). These results suggest that renal parenchymal TLR4 receptors are critical for mediating the renal toxicity of cisplatin.

Figure 8.

Cisplatin induced kidney dysfunction and renal neutrophil infiltration in chimeric mice. (A) Bone marrow chimeric mice were injected with 20 mg/kg cisplatin. Blood urea nitrogen (solid bars) and creatinine (open bars) were measured at 72 h after injection. *P < 0.05 versus WT-WT; n = 3 to 5. (B) Sections of kidney harvested 72 h after injection were stained for neutrophils as described in “Concise Methods.” Thirty ×40 fields of kidney cortex were examined from each animal. The total number of leukocytes in those 30 fields is presented. *P < 0.05 versus WT-WT; n = 3 to 5. (C) Tubular injury was assessed in PAS-stained sections using a semiquantitative scale as described in “Concise Methods.” *P < 0.05 versus WT-WT; n = 3 to 5.

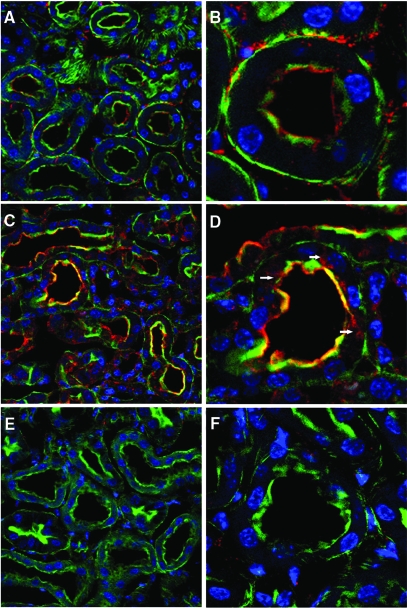

TLR4 localization in the kidney was examined by confocal microscopy (Figure 9). In control kidneys, TLR4 was localized mainly to the brush border of proximal tubules, as indicated by phalloidin colocalization. Some interstitial staining was also present, perhaps representing dendritic cells. After treatment with cisplatin, the intensity of tubular TLR4 staining appeared to increase, and the localization changed such that, in addition to the brush border, TLR4 was also present in the cytoplasm of scattered proximal tubule cells. TLR4 immunostaining was absent in kidneys from TLR4-deficient mice, demonstrating the specificity of the staining for TLR4. By RT-PCR, TLR4 expression increased approximately 10-fold after cisplatin injection (Figure 3).

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence localization of TLR4 after injection of saline or cisplatin. Representative kidney sections obtained from C57BL/6 (A-D) or Tlr4(−/−) (E and F) mice 48 h after injection. Green fluorescence represents FITC-phalloidin staining of the brush border. Red fluorescence represents TLR4 immunostaining. Blue represents DAPI staining of nuclei. (A) Saline-treated C57BL/6; TLR4 staining is seen in the interstitium and brush borders of proximal tubules (original magnification ×40). (B) A single tubule at higher magnification (original magnification ×100). (C) Cisplatin-treated C57BL/6 (original magnification ×40) shows enhanced brush border staining with clear colocalization of TLR4 and phalloidin. (D) Intracellular TLR4 staining (arrowheads) is also apparent at higher magnification (original magnification ×100). (E-F) Saline-treated Tlr4(−/−) kidneys as a negative control for TLR4 immunostaining.

DISCUSSION

Work over the past decade has established an important role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of both ischemic and toxic acute kidney injury.27–29 Thus, it is known that, in response to ischemic or toxic insults, the kidney upregulates the expression of a number of cytokines and chemokines,2,30 that adhesion molecules are upregulated,31–33 and that a variety of leukocyte populations, including neutrophils,34,35 T cells,36–38 macrophages,35 and dendritic cells,39 are either increased or activated. Moreover, blockade or deletion of certain chemokines or cytokines,2,40,41 adhesion molecules,31,32 and leukocyte populations37 ameliorates experimental acute renal failure. However, the steps that initiate the inflammatory response within the kidney remain unknown. In this regard, the current results provide important insights regarding the vital role of innate immune activation in the initiation of an inflammatory response and subsequent organ dysfunction in acute renal failure.

First, the results show that an intact TLR4 signaling pathway is necessary for the full expression of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Cenedeze et al.42 recently also reported resistance to cisplatin nephrotoxicity in mice having a point mutation in the TLR4 receptor. In addition, our findings (Supplemental data) and a recent report that appeared while this manuscript was under review43 also demonstrate a similar role for TLR4 signaling in the pathogenesis of ischemic acute renal failure. In contrast, the role of TLR4 in infection-related acute renal failure has not been firmly established. Although endotoxin-induced acute renal failure was shown to be completely dependent upon extrarenal TLR4,16 acute renal failure in the cecal ligation and puncture model of polymicrobial sepsis was independent of TLR4 signaling.44

Second, it is clear from the present studies that TLR4 is pivotal in initiating the intrarenal inflammatory response that occurs in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. The inflammatory response to cisplatin administration is characterized by an influx of neutrophils and monocytes, upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression, and increases in urinary cytokine and chemokine excretion.2,3,17,29 All of these changes were virtually completely abolished in the Tlr4-deficient mice. The pattern of gene expression in the kidney (i.e., increases in TNF-α, IL-6 and iNOS but not type I interferons)45,46 is consistent with TLR4 signaling through MyD88, as was recently reported for TLR4 signaling in ischemic renal injury.43 We previously showed that TNF-α production, acting via the TNFR2,3 contributes to cisplatin-induced cytokine and chemokine production and subsequent renal injury.2,3 The current results indicate that activation of TLR4 is a key upstream event leading to TNF-α production. Both p38 MAPK and JNK are increased in the kidneys of cisplatin-treated mice (Figure 7).7 Moreover, p38 MAPK activation contributes to TNF-α production and renal failure in response to cisplatin.4,47 The partial reduction in renal p38 MAPK activity in the Tlr4-deficient mice is consistent with a role for TLR4 in cisplatin-induced p38 MAPK activation.

In addition to TNF-α, we found that certain other pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines were reduced in the absence of TLR4. Several of these chemokines and cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-18, MCP-1, KC, and IP-10) have themselves been shown to contribute to either ischemic or toxic acute renal failure.2,41,48–51 Our observation (Figures 3 through 6) that TLR4 orchestrates the production of an array of potential mediators of renal injury makes it an attractive target for the prevention or treatment of acute renal injury.

Third, the present results are consistent with a model in which activation of TLR4 on renal parenchymal cells, such as tubular epithelial cells (Figure 8), elicits the production of TNF-α and chemokines, which leads to a subsequent inflammatory response. This result is also consistent with our recent demonstration that TNF-α production by renal parenchymal cells is key to cisplatin toxicity.52 Likewise, Wu et al.43 and Leemans et al.53 found that renal parenchymal TLR4 and TLR2, respectively, mediate renal ischemic injury. We also recognize that the measures of tissue injury in the KO→WT chimeric mice in this report (Figure 8) were somewhat lower than in WT→WT mice. Although these differences did not reach statistical significance, we cannot exclude a small role for myeloid TLR4 expression in the pathogenesis of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. There is some controversy regarding the sites of TLR4 expression in the kidney. Proximal tubule and distal tubule expression of TLR4 has been reported.13,54–56 We observed predominantly proximal tubule brush border staining in normal mouse kidney. The specificity of the immunostaining was confirmed in Tlr4-deficient mice. Zager et al.54 observed primarily proximal tubule TLR4 staining with some accentuation in the brush borders. After acute renal injury, they noted a loss of staining in the epithelium and appearance of TLR4 immunoreactivity in the tubular lumens. Kim et al.55 reported expression of TLR4 in both thick ascending limbs and proximal tubules of normal mice and only modest changes in expression levels after ischemic injury while Wolfs et al.13 found primarily distal tubule expression of TLR4 and marked upregulation after ischemic injury. We also observed an increase in renal TLR4 expression after cisplatin injury (Figure 3).

It is relevant to consider which ligand(s) might activate TLR4 during cisplatin nephrotoxicity. The localization of TLR4 to the brush border membrane suggests that the ligand is present in the tubular urine. However, the internalization of TLR4 after cisplatin could provide a mechanism for activation by intracellular ligands. We do not think that endotoxin, the traditional TLR4 ligand, is responsible for TLR4 activation in this setting. We performed our studies using barrier-raised mice and pyrogen-free solutions to reduce the likelihood of concomitant infection or introduction of exogenous endotoxin. We also measured endotoxin levels in the cisplatin solutions and in blood from mice treated with cisplatin and were unable to detect endotoxin in any of these samples (data not shown). Rather, a number of endogenous molecules act as danger signals to initiate an innate immune response via TLR receptors.19,57 Several of these putative ligands are expressed in the kidney (Figure S2). One of these, gp96, was increased after cisplatin administration. Likewise, Tamm-Horsfall protein, an abundant urinary protein, can activate TLR4.58 Further studies will be required to determine whether these, or other, ligands are responsible for TLR4 activation and subsequent renal injury during cisplatin toxicity.

In summary, the present results provide compelling evidence that activation of TLR4 present on renal parenchymal cells triggers an innate immune response that mediates cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. The identity of the ligand that activates TLR4 in this setting remains uncertain. However, because TLR4 antagonists are in clinical development,59,60 targeting this receptor may have value in preventing or treating cisplatin nephrotoxicity and other forms of acute renal failure.

CONCISE METHODS

Animal Model

Experiments were performed using 8- to 10-wk-old male C57BL/6 (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and Tlr4(−/−) mice weighing approximately 25 to 30 g. The Tlr4(−/−) mice, on a C57BL/6 background, have been described previously.14 Acute renal failure was induced with cisplatin (20 mg/kg body weight) as described previously.2–4,22 All animal protocols were approved by the IACUC of the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

Creation of Chimeric Mice

Chimeric mice were created using C57BL/6 mice and Tlr4(−/−) mice as either bone marrow donors or recipients as described previously.52 Four sets of chimeric mice were created: WT→WT; WT→KO; KO→WT; and KO→KO. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions before and after the bone marrow transplantation.

Renal Function

Renal function was assessed by measurements of blood urea nitrogen (VITROS DT60II Chemistry slides, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY) and serum creatinine (DZ072B, Diazyme Labs, Poway, CA).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Tubular injury was assessed in periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained sections using a semiquantitative scale as described previously.2 Immunohistochemistry for neutrophils was performed with a rat anti-murine neutrophil primary antibody (MCA 771 GA, Serotec, Raleigh, NC) followed by a biotinylated anti-rat IgG secondary antibody. Thirty X40 fields from each kidney were examined for quantitation of neutrophils.

TLR4 was localized by immunofluorescence of paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections. Kidneys were perfusion-fixed in situ with 50 ml phosphate-buffered saline followed by 50 ml 4% paraformaldehyde and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The kidneys were then transferred to a 20% sucrose solution for 24 h before 10-μm cryosections were cut. A goat polyclonal TLR4 antibody (catalog no. sc-16240, Santa Cruz) was applied as the primary antibody. For improved detection of TLR4, we used an unconjugated secondary rabbit anti-goat antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and a Cy5-conjugated tertiary donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA) as described by El-Achkar et al.56 Brush borders were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-phalloidin and nuclei were stained with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The images were collected with a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal microscope. Kidneys from Tlr4-deficient mice served as negative controls for the immunostaining.

Quantitation of mRNA by Real-time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was performed in an Applied Biosystems Inc. 7700 Sequence Detection System (Foster City, CA) as described previously.3,17,47 The primer sets used were: mouse ICAM-1 (forward: AGATCACATTCACGGTGCTG; reverse: CTTCAGAGGCAGGAAACAGG), IL-2 (forward: AACCTGAAACTCCCCAGGAT; reverse TCATCGAATTGGCACTCAAA), TNF-α (forward: GCATGATCCGCGACGTGGAA; reverse: AGATCCATGCCGTTG GCCAG), IL-1β (forward: CTCCATGAGCTTTGTACAAGG; reverse: TGCTGATGTACCAGTTGGGG), IL-18 (forward: ACTGTACAACCGCAGTAATACGG; reverse: AGTGAACATTACAGATTTATCCC), IL-6 (forward: GATGCTACCAAACTGGATATAATC; reverse: GGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTCTGTG), KC (forward: GCTGGGATTCACCTCAAGAA; reverse: TGGGGACACCTTTTAGCATC), IP-10 (forward: GGTCTGAGTGGGACTCAAGG; reverse: CGTGGCAATGATCTCAACAC), MCP-1 (forward: ATGCAGGTCCCTGTCATG; reverse: GCTTGAGGTGGTTGTGGA), RANTES (forward: GATGGACATAGAGGACACAACT; reverse: TGGGACGGCAGATCTGAGGG), TLR4 (forward: CCTCTGCCTTCACTACAGAGACTTT; reverse: TGTGGAAGCCTTCCTGGAG), IFN-α (forward: TGGCAGTGATGAGCTACTGG; reverse: ATCTGCTGGGTCAGCTCAGT), IFN-β (forward: CCCTATGGAGATGACGGAGA; reverse: CTGTCTGCTGGTGGAGTTCA), and iNOS (forward: CCCTGCTTTGTGCGAAGTGT; reverse: ATGCGGCCTCCTTTGAGC). The amount of DNA was normalized to the β-actin signal amplified in a separate reaction (forward: AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC; reverse: CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT).

Cytokine/Chemokine Quantitation

Urine, kidney, and serum cytokines and chemokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IP-10, MCP-1, and RANTES) were measured using a bead-based multiplexed cytokine analysis kit (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO) using a Luminex-100 system (Luminex, Austin, TX).

Western Blot and p38 MAPK Assays

Western blot analysis using antibodies to JNK and phospho-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and p38 MAPK activity were performed as described previously.4

Statistical Methods

All assays were performed in duplicate. The data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired, two-tailed t test for single comparisons or ANOVA for multiple comparisons.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (RO1 DK063120 to W.B.R.), the Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service, Tobacco Settlement Funds administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, and an Alyce Spector Research Grant from the Kidney Foundation of Central Pennsylvania.

The authors thank Ms Wei Wei Wang for the excellent technical support.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ries F, Klastersky J: Nephrotoxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy with special emphasis on cisplatin toxicity. Am J Kidney Dis 13: 368–379, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: TNF-α mediates chemokine and cytokine expression and renal injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J Clin Invest 110: 835–842, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: TNFR2-mediated apoptosis and necrosis in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 54: F610-F618, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: p38 MAP kinase inhibition ameliorates cisplatin nephrotoxicity in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F166-F174, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuruya K, Ninomiya T, Tokumoto M, Hirakawa M, Matsutani K, Taniguchi M, Fukuda K, Kanai H, Kishihara K, Hirakata H, Iida M: Direct involvement of the receptor-mediated apoptotic pathways in cisplatin-induced renal tubular cell death. Kidney Int 63: 72–82, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuruya K, Tokumoto M, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa M, Matsutani K, Taniguchi M, Fukuda K, Kanai H, Hirakata H, Iida M: Antioxidant ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal tubular cell death through inhibition of death receptor-mediated pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F208-F218, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: Cisplatin increases TNF-α mRNA stability in kidney proximal tubule cells. Renal Failure 28: 583–592, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akira S: Toll-like receptors: Lessons from knockout mice. Biochem Soc Trans 28: 551–556, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West PA, Koblansky AA, Ghosh S: Recognition and signaling by Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 409–437, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothfuchs AG, Trumstedt C, Wigzell H, Rottenberg ME: Intracellular bacterial infection-induced IFN-gamma is critically but not solely dependent on Toll-like receptor 4-myeloid differentiation factor 88-IFN-alpha beta-STAT1 signaling J Immunol 172: 6345–6353, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuboi N, Yoshikai Y, Matsuo S, Kikuchi T, Iwami, K-I, Nagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Matsuguchi T: Roles of Toll-like receptors in C-C chemokine production by renal tubular epithelial cells. J Immunol 169: 2026–2033, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anders, H-J, Banas B, Schlondorff D: Signaling danger: Toll-like receptors and their potential roles in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 854–867, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfs, TGAM, Buurman WA, van Schadewijk A, de Vries B, Daemen MARC, Hiemstra PS, van 't Veer C: In vivo expression of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 by renal epithelial cells: IFN-γ and TNF-α mediated up-regulation during inflammation. J Immunol 168: 1286–1293, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S: Cutting edge. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: Evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol 162: 3749–3752, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu, M-Y, Huffel CV, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B: Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: Mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282: 2085–2088, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham PN, Wang Y, Guo R, He G, Quigg RJ: Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in endotoxin-induced acute renal failure. J Immunol 172: 2629–2635, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramesh G, Zhang B, Uematsu S, Akira S, Reeves WB: Endotoxin and cisplatin synergistically induce renal dysfunction and cytokine production in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F325-F332, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohashi K, Burkart V, Flohe S, Kolb H: Cutting edge: Heat shock protein 60 is a putative endogenous ligand of the Toll-like receptor-4 complex. J Immunol 164: 558–561, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsan, M-F, Gao B: Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol 76: 514–519, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhai Y, Shen X-d, O'Connell R, Gao F, Lassman C, Busuttil RW, Cheng G, Kupiec-Weglinski JW: Cutting edge: TLR4 activation mediates liver ischemia/reperfusion inflammatory response via IFN regulatory factor 3-dependent MyD88-independent pathway. J Immunol 173: 7115–7119, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oyama, J-i, Blais C Jr, Liu X, Pu M, Kobzik L, Kelly RA, Bourcier T: Reduced myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in Toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice. Circulation 109: 784–789, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: Salicylate reduces cisplatin nephrotoxicity by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α. Kidney Int 65: 490–498, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park KM, Chen A, Bonventre JV: Prevention of kidney ischemia/reperfusion-induced functional injury and JNK, p38, and MAPK kinase activation by remote ischemic pretreatment. J Biol Chem 276: 11870–11876, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, Zhang Q, Tian L, Wang Y, Siddik ZH, Mills GB, Claret FX: Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 278: 19245–19256, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y: Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 275: 90–94, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vabulas RM, Braedel S, Hilf N, Singh-Jasuja H, Herter S, Ahmad-Nejad P, Kirschning CJ, da Costa C, Rammensee, H-G, Wagner H, Schild H: The endoplasmic reticulum-resident heat shock protein Gp96 activates dendritic cells via the Toll-like receptor 2/4 pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 20847–20853, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okusa M: The inflammatory cascade in acute ischemic renal failure. Nephron 90: 133–138, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonventre JV, Zuk A: Ischemic acute renal failure: an inflammatory disease? Kidney Int 66: 480–485, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: Inflammatory cytokines in acute renal failure. Kidney Int 91: S56-S61, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemay S, Rabb H, Postler G, Singh A: Prominent and sustained up-regulation of GP130-signaling cytokines and of the chemokine MIP-2 in murine renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation 69: 959–963, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly KJ, Williams WW, Colvin RB, Bonventre JV: Antibody to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 protects the kidney against ischemic injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 812–816, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly KJ, Meehan SM, Colvin RB, Williams WW, Bonventre JV: Protection from toxicant-mediated renal injury in the rat with anti-CD54 antibody. Kidney Int 56: 922–931, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takada M, Nadeau K, Shaw G, Marquette K, Tilney N: The cytokine-adhesion molecule cascade in ischemia/reperfusion injury of the rat kidney. J Clin Invest 99: 2682–2690, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng J, Kohda Y, Chiao H, Wang Y, Hu X, Hewitt S, Miyaja T, McLeroy P, Nibhanupudy B, Li S, Star R: Interleukin-10 inhibits ischemic and cisplatin-induced acute renal injury. Kidney Int 60: 2118–2128, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ysebaert DK, De Greef KE, Vercauteren SR, Ghielli M, Verpooten GA, Eyskens EJ, De Broe ME: Identification and kinetics of leukocytes after severe ischemia/reperfusion renal injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 1562–1574, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabb H, Daniels F, O'Donnell M, Haq M, Saba S, Keane W, Tang W: Pathophysiological role of T lymphocytes in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F525-F531, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burne M, Daniels F, Ghandourm A, Mauiyyedi S, Colvin R, O'Donnell M, Rabb H: Identification of the CD4+ T cells as a major pathogenic factor in ischemic acute renal failure. J Clin Invest 108: 1283–1290, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ascon DB, Lopez-Briones S, Liu M, Ascon M, Savransky V, Colvin RB, Soloski MJ, Rabb H: Phenotypic and functional characterization of kidney-infiltrating lymphocytes in renal ischemia reperfusion injury. J Immunol 177: 3380–3387, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong X, Swaminathan S, Bachman LA, Croatt AJ, Nath KA, Griffin MD: Antigen presentation by dendritic cells in renal lymph nodes is linked to systemic and local injury to the kidney. Kidney Int 68: 1096–1108, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel NSA, Chatterjee PK, Di Paola R, Mazzon E, Britti D, De Sarro A, Cuzzocrea S, Thiemermann C: Endogenous interleukin-6 enhances the renal injury, dysfunction, and inflammation caused by ischemia/reperfusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312: 1170–1178, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furuichi K, Wada T, Iwata Y, Kitagawa K, Kobayashi, K-i, Hashimoto H, Ishiwata Y, Tomosugi N, Mukaida N, Matsushima K, Egashira K, Yokoyama H: Gene therapy expressing amino-terminal truncated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 prevents renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1066–1071, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cenedeze MA, Goncalves GM, Feitoza CQ, Wang PMH, Damiao MJ, Bertocchi APF, Pacheco-Silva A, Camara NOS: The role of Toll-like receptor 4 in cisplatin-induced renal injury. Transplant Proc 39: 409–411, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu H, Chen G, Wyburn KR, Yin J, Bertolino P, Eris JM, Alexander SI, Sharland AF, Chadban SJ: TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 117: 2847–2859, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dear JW, Yasuda H, Hu X, Hieny S, Yuen PST, Hewitt SM, Sher A, Star RA: Sepsis-induced organ failure is mediated by different pathways in the kidney and liver: Acute renal failure is dependent on MyD88 but not renal cell apoptosis. Kidney Int 69: 832–836, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toshchakov V, Jones BW, Perera P-Y, Thomas K, Cody MJ, Zhang S, Williams BRG, Major J, Hamilton TA, Fenton MJ, Vogel SN: TLR4, but not TLR2, mediates IFN-[beta]-induced STAT1[alpha]/[beta]-dependent gene expression in macrophages. Nat Immunol 3: 392–398, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S: Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 11: 115–122, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramesh G, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Reeves WB: Endotoxin and cisplatin synergistically stimulate TNF-α production by renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F812-F819, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melnikov VY, Ecder T, Fantuzzi G, Siegmund B, Lucia MS, Dinarello CA, Schrier RW, Edelstein CL: Impaired IL-18 processing protects caspase-1-deficient mice from ischemic acute renal failure. J Clin Invest 107: 1145–1152, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kielar ML, John R, Bennett M, Richardson JA, Shelton JM, Chen L, Jeyarajah DR, Zhou XJ, Zhou H, Chiquett B, Nagami GT, Lu CY: Maladaptive role of IL-6 in ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3315–3325, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miura M, Fu X, Zhang Q-W, Remick DG, Fairchild RL: Neutralization of Groα and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol 159: 2137–2145, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiorina P, Ansari MJ, Jurewicz M, Barry M, Ricchiuti V, Smith RN, Shea S, Means TK, Auchincloss H Jr, Luster AD, Sayegh MH, Abdi R: Role of CXC chemokine receptor 3 pathway in renal ischemic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 716–723, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang B, Ramesh G, Norbury C, Reeves WB: Cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-a produced by renal parenchymal cells. Kidney Int 72: 37–44, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leemans JC, Stokman G, Claessen N, Rouschop KM, Teske GJD, Kirschning CJ, Akira S, van der Poll T, Weening JJ, Florquin S: Renal-associated TLR2 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the kidney. J Clin Invest 115: 2894–2903, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zager RA, Johnson ACM, Lund S, Randolph-Habecker J: Toll-like receptor (TLR4) shedding and depletion: acute proximal tubular cell responses to hypoxic and toxic injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F304-F312, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim BS, Lim SW, Li C, Kim JS, Sun BK, Ahn KO, Han SW, Kim J, Yang CW: Ischemia-reperfusion injury activates innate immunity in rat kidneys. Transplantation 79: 1370–1377, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Achkar TM, Huang X, Plotkin Z, Sandoval RM, Rhodes GJ, Dagher PC: Sepsis induces changes in the expression and distribution of Toll-like receptor 4 in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1034-F1043, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bianchi, ME: DAMPs PAM: Ps and alarmins: All we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol 81: 1–5, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saemann MD, Weichhart T, Zeyda M, Staffler G, Schunn M, Stuhlmeier KM, Sobanov Y, Stulnig TM, Akira S, von Gabain A, von Ahsen U, Horl WH, Zlabinger GJ: Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein links innate immune cell activation with adaptive immunity via a Toll-like receptor-4-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest 115: 468–475, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stover AG, Da Silva Correia J, Evans JT, Cluff CW, Elliott MW, Jeffery EW, Johnson DA, Lacy MJ, Baldridge JR, Probst P, Ulevitch RJ, Persing DH, Hershberg RM: Structure-activity relationship of synthetic Toll-like receptor 4 agonists. J Biol Chem 279: 4440–4449, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mullarkey M, Rose JR, Bristol J, Kawata T, Kimura A, Kobayashi S, Przetak M, Chow J, Gusovsky F, Christ WJ, Rossignol DP: Inhibition of endotoxin response by E5564, a novel Toll-like receptor 4-directed endotoxin antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 304: 1093–1102, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.