Abstract

Background

We investigated the impact of enhancing brief cognitive behavioral therapy with motivational interviewing techniques for cocaine abuse or dependence, using a focused intervention paradigm.

Methods

Participants (n=74) who met current criteria for cocaine abuse or dependence were randomized to 3-session cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or 3-session enhanced CBT (MET + CBT), which included an initial session of motivational enhancement therapy (MET). Outcome measures included treatment retention, process measures (e.g., commitment to abstinence, satisfaction with treatment), and cocaine use.

Results

Participants who received the MET+CBT intervention attended more drug treatment sessions following the study interventions, reported significantly greater desire for abstinence and expectation of success, and they expected greater difficulty in maintaining abstinence compared to the CBT condition. There were no differences across treatment conditions on cocaine use.

Conclusions

These findings offer mixed support for the addition of MET as an adjunctive approach to CBT for cocaine users. In addition, the study provides evidence for the feasibility of using short-term studies to test the effects of specific treatment components or refinements on measures of therapy process and outcome.

Keywords: cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement therapy, cocaine

1. Introduction

The effectiveness of CBT for improving treatment outcomes among cocaine-using populations has been documented (Carroll et al., 2000; 2004; Rawson et al., 2002; Rohsenow et al., 2000). Although CBT’s effects are comparatively durable, a relative weakness of CBT is that its effects on early retention are mixed and it does not strongly address the individual’s motivation and engagement, aspects more specifically targeted in motivational enhancement therapy (Miller and Rollnick, 2002). MET has demonstrated efficacy comparable to other standard substance abuse treatments (Burke et al., 2003; Project Match Research Group, 1998; Stephens et al., 2000) and has been conceptualized as an adjunctive or preparatory treatment, particularly for more severe drug use disorders (Miller et al., 2003; Rosenhow et al., 2004).

An emerging treatment strategy is to combine empirically-supported therapies (or their components) to address their relative strengths and weaknesses. Although some studies have found support for the effectiveness of CBT-MET combinations (MTP Research Group, 2004), few empirical evaluations have examined whether standard approaches such as CBT are improved by combining components from other approaches and whether such combinations work in the manner hypothesized (Kazdin, 1986, 2004; Kazdin and Nock, 2003). The standard evaluative strategy is to conduct full-scale randomized clinical trials (Jacobson et al., 1996), which is costly and time-consuming. An alternate, and potentially more efficient strategy is to conduct smaller highly-focused trials evaluating the effect of specific components on treatment outcome (Kazdin, 1986, 2004; Kazdin and Nock, 2003).

Using a short-term intervention paradigm, participants were randomized to two treatment entry interventions prior to standard substance abuse treatment: CBT only, and MET+CBT to evaluate whether the addition of MET to CBT improves treatment outcomes. Changes in treatment motivation, treatment satisfaction, and retention were evaluated as primary outcomes, with cocaine use a secondary outcome given the brief nature of the protocol interventions and the anticipated effect of MET on process measures.

2. Methods

2.1 Sample

Participants were recruited through an outpatient substance abuse clinic. Seventy-four eligible individuals who met current criteria for cocaine abuse (11%) or dependence (89%) were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions; MET+CBT (n=38) or CBT (n=36). Exclusion criteria included current opiate abuse or dependence, a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, current suicidal or homicidal plans and intent, or a pending legal case.

2.2 Intervention conditions

Both brief introductory interventions were manual-guided and delivered across three 60-minute sessions held weekly. Participants were required to complete the three sessions within a 7-week timeframe. The CBT condition included sessions described in standard CBT manuals (Carroll, 1998; Kadden et al., 1992; Monti et al., 1989). Session one covered the rationale for CBT and high-risk situations for resumption of cocaine use. Session two addressed managing cocainerelated craving, and session three addressed general problem-solving skills. In the MET+CBT condition, session one focused on motivational interviewing techniques; thus, the therapist sought to increase the participant’s commitment to change by raising their awareness of personal consequences resulting from their drug use (Miller et al., 1992). Therapists were encouraged to use a therapeutic stance in which they expressed empathy, avoided argumentation, and supported self-efficacy. Following the MET session, the CBT sessions covered the rationale for a cognitive-behavioral approach, high-risk situations for resumption of cocaine use, and coping with craving (session 2) and problem solving skills (session 3). During these CBT sessions, however, therapists were instructed to maintain a MET style throughout, by asking open-ended questions, rolling with resistance, and encouraging commitment to change.

Eleven clinicians (64% female) provided treatment in both therapy conditions. Primarily Caucasian (9% African American), they had a range of training (1 M.D., 2 M.S.W., 7 completing Ph.D) and all were experienced in treating substance abuse. Clinicians received didactic training and completed at least one training case for each treatment condition. Ongoing Ph.D.-level clinical case supervision was provided.

2.3 Procedures

Individuals were invited to participate following their initial triage appointment. After providing written informed consent, participants completed baseline assessments and eligible individuals were randomized to therapy condition. Therapists, participants, and staff were unaware of the therapy assignment until the patient showed for session one. At the end of each session, participants completed assessments and a urine drug screen. These assessments were collected by research staff blind to the therapy condition. At the end of session three, participants were referred for continued substance abuse treatment at the same clinic. Clinic staff determined treatment modality, frequency, and therapeutic approach for ongoing substance use treatment. During follow-up interviews (week 8, 16), participants reported on drug and alcohol use, commitment to abstinence, number of formal drug treatment sessions attended, and provided urine samples.

2.4 Assessments

Diagnostic information about substance abuse disorders was obtained with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Spitzer et al., 1995). The Time-Line-Follow-Back Assessment Method (Sobell et al., 1980) was used to assess cocaine, alcohol, and other drug use for the thirty days prior to entering the study, and during the treatment and follow-up phases. Urine samples (cocaine, marijuana, opiates, benzodiazepines) and breath alcohol were obtained at each appointment.

Several self-report measures were administered at baseline, after each therapy session, and at the follow-up sessions (week 8, 16). The Thoughts about Abstinence Scale (TAAS; Hall et al., 1990) assessed treatment motivation. Complete abstinence goal (from all substance use) versus all other responses were dichotomized. Three additional items measured desire to quit, expectation of success in quitting, and anticipated difficulty in remaining abstinent after quitting. The Client Satisfaction Scale (CSQ; Larsen et al., 1979) measured general satisfaction with services. The Patient Therapy Session Report (PTSR; Orlinsky and Howard, 1975) measured the degree to which they felt helped and understood by the therapist.

2.5 Data Analysis

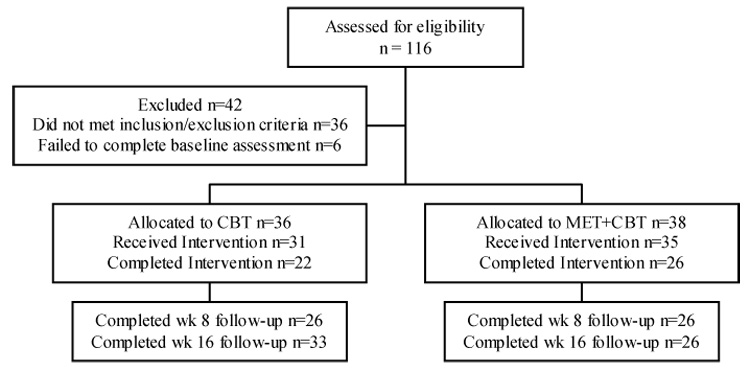

Baseline differences in demographic and pretreatment variables between therapy conditions were assessed by t-tests and chi-square tests (n=74). ANOVAS were used to evaluate outcomes on the final sample of 66 individuals who completed at least one session of study treatment. [INSERT FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE] For process measures and cocaine use outcomes, separate random effects regression models were used to evaluate treatment differences across baseline and the treatment phase, and then across the follow-up timepoints. As retention outcomes were not normally distributed, we used both survival analysis and median analysis to assess treatment differences in retention.

Figure 1.

Diagram of participant recruitment, retention, and follow-up.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Description

There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics or pre-treatment motivation across therapy conditions. [INSERT TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE] Assessment of past 30-day drug use indicated greater frequency [F(1,66)=6.93,p<.05] and quantity [F(1,66)=.51,p<.10] of cannabis use in the CBT condition.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Condition

| CBT (n = 36) | MET + CBT (n = 38) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, sd) | 34.9 (7.2) | 35.0 (7.3) | |

| Sex (n, %) | Male | 27 (75.0) | 27 (71.0) |

| Female | 9 (25.0) | 11 (29.0) | |

| Race (n, %) | White | 12 (33.3) | 21 (55.3) |

| Black | 19 (52.8) | 17 (44.7) | |

| Hispanic | 5 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Martial Status (n, %) | Never Married | 18 (50.0) | 21 (55.3) |

| Married or Cohabitating | 12 (33.3) | 11 (28.9) | |

| Divorced or Separated | 6 (16.7) | 6 (15.8) | |

| Education (n, %) | College Graduate | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.3) |

| Partial College | 6 (16.7) | 13 (34.2) | |

| High School Graduate | 14 (38.9) | 10 (26.3) | |

| Less than High School | 15 (41.7) | 13 (34.2) | |

| Employment Status (n, %) | Full-time | 11 (30.6) | 17 (44.7) |

| Part-time | 3 (8.3) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Unemployed | 22 (61.1) | 16 (42.1) | |

| Lifetime Prevalence (n, % | Cocaine Abuse | 29 (80.6) | 33 (86.8) |

| Dependence | 32 (88.9) | 36 (94.7) | |

| Alcohol Abuse | 8 (22.2) | 12 (31.6) | |

| Dependence | 23 (63.9) | 24 (63.2) | |

| Cannabis Abuse | 17 (47.2) | 17 (44.7) | |

| Dependence | 9 (25) | 10 (26.3) | |

| Opioid Abuse | 2 (5.6) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Dependence | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.3) | |

| Total Frequency past 30-days (mean, sd) | Cocaine | 6.5 (5.1) | 7.8 (7.1) |

| Alcohol | 8.1 (5.8) | 9.4 (7.5) | |

| Cannabis | 4.9 (8.1) | 1.3 (2.7)** | |

| Cigarettes | 24.9 (9.4) | 22.5 (11.8) | |

| Total Quantity Past 30 days (mean, sd) | n = 32 | n = 36 | |

| Cocaine ($) | 301.56 (296.2) | 87.09 (89.0) | |

| Alcohol (# drinks) | 54.25 (83.6) | 58.73 (66.2) | |

| Cannabis (# joints) | 14.02 (37.7) | 2.22 (5.5)* | |

| Cigarettes | 341.34 (278.74) | 376.68 (348.85) | |

| Thoughts about Abstinence Scale (mean, sd) | n = 36 | n = 38 | |

| Desire to quit (range 1–10) | 8.8 (1.9) | 8.7 (1.8) | |

| Expectation of success (range 1–10) | 7.5 (2.0) | 7.6 (2.2) | |

| Ease of maintaining abstinence (range 1–10) | 4.40 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.7) | |

| Total Abstinence Goal a(n, %) | 31 (88.6) | 32 (86.5) | |

| Beck Depression Inventory (mean, sd) | 8.6 (6.1) | 7.0 (5.0) | |

Percent who responded “I want to quit using once and for all, to be totally abstinent, and never use ever again for the rest of my life”

p < .10

p < .05

3.2 Treatment Retention

Mean sessions completed (CBT=2.19,SD=1.14; MET+CBT=2.39,SD=1.00) and percentage of participants completing all three sessions (CBT=61%, MET+CBT=68%), were comparable across conditions (p>.05). There were no significant effects of treatment on completion of the three therapy sessions as assessed by survival or median effects. While there was no effect of treatment on the proportions attending ongoing drug treatment during the 8-week follow-up period (MET+CBT=65%, CBT=60%), there was a significant effect on the number of sessions attended [F(1,65)=5.40,p<.03]. Participants assigned to MET+CBT attended more drug treatment sessions (mean=5.66,SD=9.24) than those who received CBT (mean=1.57,SD=2.69).

3.3 Process Measure

Participants reported an increase in overall treatment satisfaction over time [PTSR; z=4.00,p<.005], with no effect of treatment condition. No effects were demonstrated for the CSQ. For the TAAS, there were significant treatment-by-time interactions across the therapy sessions. By the end of session three, participants receiving MET+CBT reported greater desire for abstinence (z=1.94,p<.05; mean=9.14 vs. 8.30), greater expectation of success (z=2.19,p<.05; mean=8.43 vs. 7.30), and expected more difficulty in maintaining abstinence after quitting (z=−3.62,p<.005; mean=7.24 vs. 4.80) than those assigned to CBT. These effects were not sustained during the follow-up period. No effects were found for the TAAS item assessing treatment goal.

3.4 Cocaine Use by Therapy Condition during Treatment

Frequency and quantity of cocaine use decreased from baseline through the treatment phase. There were no significant treatment-by-time effects. Frequency of cocaine use decreased from 1.81 (SD=1.48) to 1.18 (SD=1.42;z=−4.83,p<.001) days per week and quantity of cocaine use decreased from $102.56 (SD=115.42) to $24.41 (SD=53.68;z =−5.36,p<.001) per week. There was no effect of treatment condition on proportions of cocaine positive urines collected after each session (MET+CBT session 1=47%, 2=46%, 3=42%; CBT session 1=53%, 2=52%, 3=50%) or follow-up appointments (MET+CBT week 8=63%, 16=56%; CBT week 8=52%, 16=58%).

4. Discussion

This study examined whether enhancing CBT with MET would primarily increase client participation, engagement, and commitment to abstinence, and secondarily decrease cocaine use during the initial phase of substance abuse treatment. While there were no differences in completion rates for the three therapy sessions, participants who received MET+CBT attended more treatment sessions during the follow-up period. This finding is consistent with a number of emerging studies suggesting that motivational enhancement, as a preparatory intervention, may enhance treatment engagement (Carroll et al., 2006; Connors et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2003). With regard to the process measures, those who received MET+CBT reported significantly greater desire for abstinence, greater expectations of success, and also expected greater difficulty in maintaining abstinence after quitting compared to those who received CBT, although these differences were not maintained by follow-up. Further, MET+CBT participants did not report higher commitment to abstinence, a factor associated with positive treatment outcome across substances of abuse (Hall et al., 1990, 1991; Elal-Lawrence et al., 1987; Wasserman et al., 1998). Finally, we did not demonstrate any differences in cocaine use. Other studies examining the addition of MET as a preparatory treatment have documented differences in alcohol or drug use outcomes (Connors et al., 2002), whereas others have not (Miller et al., 2003).

Several limitations of this study should be noted, particularly the limited sample and hence, statistical power. Second, the same therapists provided both interventions, and while supervised, treatment adherence was not systematically evaluated and there were baseline differences in cannabis use across treatment conditions. Third, the sample homogeneity and high level of therapist education may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, enhancing CBT with MET may have fundamentally changed how CBT was delivered to participants, and warrants further investigation. Overall, the findings provided only mixed support for enhancing CBT with MET. The targeted approach used here may be useful for evaluating specific treatment components or refinements on measures of therapy process and outcome.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; A cognitive-behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction (NIH Publication 98-4308) 1998

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Kunkel LE, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Morgenstern J, Obert JL, Polcin D, Snead N, Woody GE. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive-behavioral therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: A randomized placebo controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;64:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry R, Frankforter T, Nuro KF, Ball SA, Fenton LR, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Walitzer KS, Dermen KH. Preparing patients for alcoholism treatment: effects on treatment participation and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1161–1169. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RM, Baer JS, Saxon AJ, Kivlahan DR. Brief motivational feedback improves post-incarceration treatment contact among veterans with substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elal-Lawrence G, Slade PD, Dewey ME. Treatment and follow-up variables discriminating abstainers, controlled drinkers and relapsers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:39–46. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:175–181. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Effects of commitment to abstinence, positive moods, stress, and coping on relapse to cocaine use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:526–532. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koerner K, Gollan JK, Gortne E, Prince SE. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden R, Carroll KM, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P, Abrams D, Litt M, Hester R. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series Volume 3, DHHS Publication No. (ADM) 92-1895. 1992

- Kazdin AE. Comparative outcome studies of psychotherapy: Methodological issue and strategies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:95–105. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatments: Challenges and priorities for practice and research. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:923–940. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan JS. Motivational interviewing in drug services: a randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:754–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual. DHHS Publication No. (ADM) 92-1894. 1992

- Monti PM, Abrams DB, Kadden RM, Cooney NL. Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide. New York: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- MTP Research Group. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:455–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlinsky DE, Howard KI. Varieties of psychotherapeutic experience. New York: Colombia Teachers College Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to patient heterogeneity: Treatment main effects and matching effects on drinking during treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:631–639. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann MJ, Shoptaw S, Farabee D, Reiber C, Ling W. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:817–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Martin RA, Colby SM, Myers MG, Gulliver SB, Brown RA, Mueller TI, Gordon A, Abrams DB. Motivational enhancement and coping skills training for cocaine abusers: Effects on substance use outcomes. Addiction. 2004;99:862–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Martin RA, Michalec E, Abrams DB. Brief coping skills treatment for cocaine abuse: 12-month substance use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:515–520. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Cooper AM, Cooper AM, Sanders B. Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness. In: Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Ward E, editors. Evaluating alcohol and drugs abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1980. pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. 722 West 168th Street, New York, New York 10032: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman DA, Weinstein MG, Havassy BE, Hall SM. Factors associated with lapses to heroin use during methadone maintenance. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;52:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]