The occurrence of 11 cases of inhalational anthrax associated with letters containing Bacillus anthracis powder sent through the United States Postal Service in Florida, New York, New Jersey, and in Washington, DC, in September and October 2001 has emphasized the necessity for health care practitioners to be familiar with the manifestations of inhalational anthrax. A wide variety of health care practitioners, including radiologists and pathologists, have the potential to alert other physicians to the possibility of inhalational anthrax because the clinical manifestations of early disease are nonspecific, consisting of flulike symptoms, fever, sweats, malaise, and myalgias. In the absence of known exposure to B. anthracis, the appropriate cultures may not be obtained, and potentially life-saving therapy may not be instituted in a timely manner. The predicted case fatality of inhalational anthrax from historical data was approximately 90% [1]. The United States outbreak showed that with early diagnosis and institution of antimicrobial therapy, mortality can be substantially reduced [2]. In addition, timely identification of inhalational anthrax cases is important so that appropriate public health and law enforcement officials can be notified and can take necessary measures to limit morbidity and mortality. Such notification allows other patients and clinicians to be alerted about the potential for new exposure and allows evidence about the perpetrator to be collected expeditiously.

The clinical histories of the 11 cases of bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax in the United States have been described in detail in several recent publications [2–7]. Here we describe the clinical course of two of the affected patients, with emphasis on imaging findings, in an effort to increase clinician awareness about this disease. We also provide correlation with the postmortem examination of the fatal case.

Case Report 1

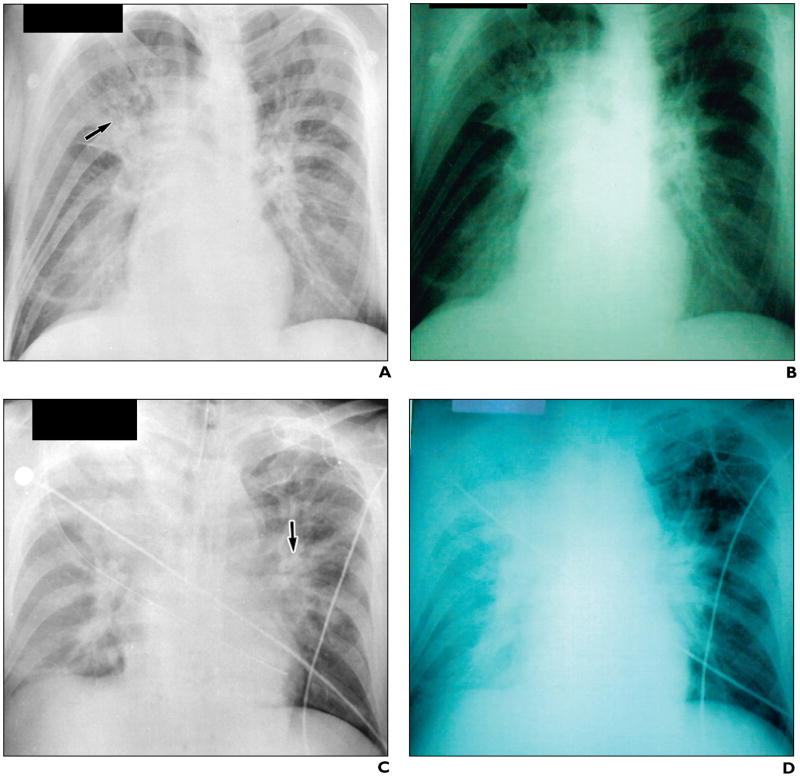

On October 16, 2001, a 47-year-old male postal worker developed progressive nausea, abdominal pain, and flulike symptoms that prompted him to seek emergency medical care 5 days later (October 21). Chest radiographs obtained on his presentation to the emergency department revealed a subtle parenchymal lung infiltrate limited to the right suprahilar region [5] (Fig. 1A). The patient was sent home with a presumptive diagnosis of gastroenteritis. He continued to deteriorate and on the following day was taken to the hospital by ambulance. When he arrived, signs of shock were already present. Sequential chest radiographs at 26, 30, and 32 hr after the initial chest radiograph showed rapid progression of air-space disease, perihilar infiltrates, pleural effusions, and mediastinal widening (Figs. 1B–1D) [5]. He was pronounced dead a few hours later, on October 22, despite aggressive medical therapy. Blood cultures grew B. anthracis within 6 hr of incubation.

Fig 1. 47-year-old man with inhalational anthrax and gastrointestinal anthrax.

A, Chest radiograph on presentation shows subtle right suprahilar infiltrate (arrow). (Reprinted with permission from [5])

B–D, Sequential chest radiographs between 26 and 32 hr later show rapid progression of patchy hilar and peribronchial infiltrates (arrow, C), blurring of mediastinal borders, and eventual opacification of right hemithorax (D). (Reprinted with permission from [5])

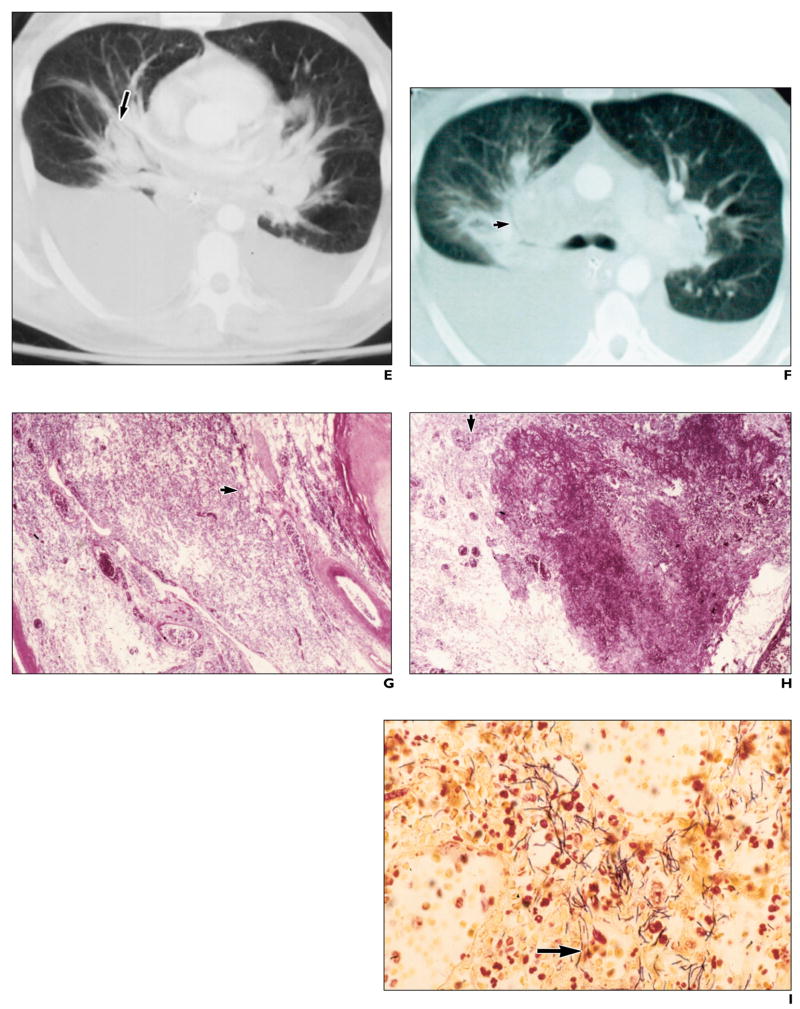

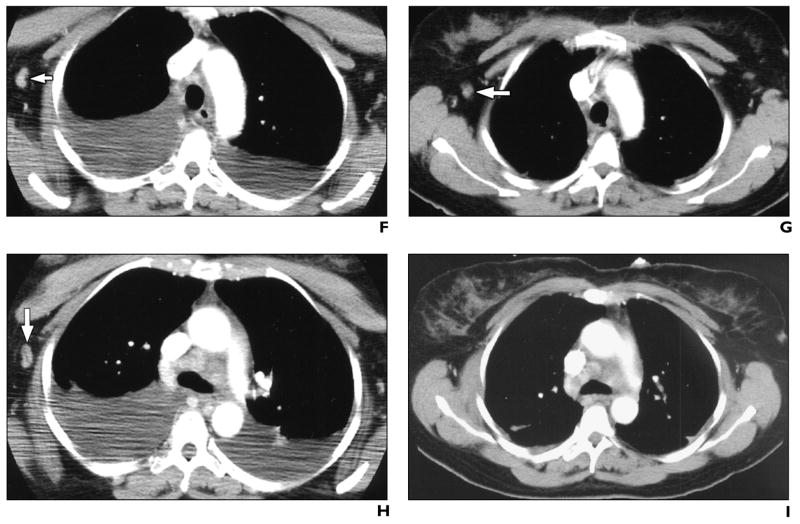

E and F, Contrast-enhanced chest CT scans reveal perihilar parenchymal lung disease (arrow, E) widening central silhouette, hilar adenopathy, pleural effusions, and peribronchial infiltrates as well as patchy peribronchial air-space disease, especially on right (arrow, F).

G, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen shows hilar soft tissue with perivascular and peribronchial hemorrhage (arrow). (H and E, ×10)

H, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of hilar soft tissue shows hemorrhage and necrosis (arrow). (H and E, ×20)

I, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of hilar soft tissue shows abundant gram-positive bacilli (arrow). (Brown–Brenn, ×100)

J and K, Contrast-enhanced CT scans with mediastinal window settings show high-attenuation subcarinal lymph node (arrow, J), signifying hemorrhagic lymphadenitis, and mediastinal blood (arrow, K), signifying hemorrhagic mediastinitis. Well-defined high attenuation in node differentiates this from free blood in mediastinum, seen as thin wisps of high attenuation with ill-defined borders. (K reprinted with permission from [5])

L, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of mediastinal soft tissue shows hemorrhage (arrow). (H and E, ×20)

M, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of hilar lymph node shows hemorrhagic necrotizing lymphadenitis (arrow). (H and E, ×20)

N, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of hilar lymph node shows abundant gram-positive bacilli (arrow). (Brown–Brenn, ×64)

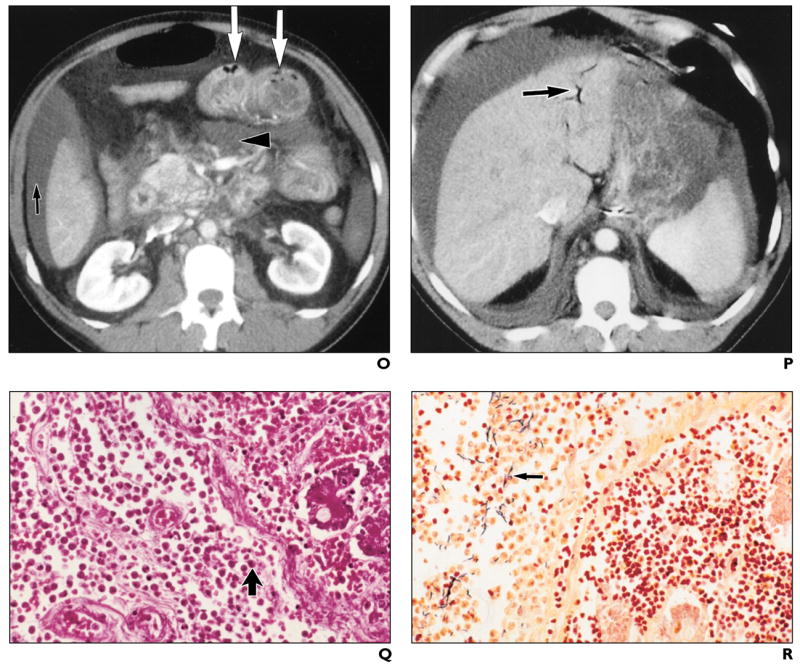

O and P, Abdominal CT scans show ascites (black arrow, O), mesenteric inflammation and edema (arrowhead, O), small-bowel distention and wall thickening with pneumatosis (white arrows, O), and portal venous gas (arrow, P). (O reprinted with permission from [5])

Q, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of segment of affected small bowel shows necrotizing infection with abundant neutrophils (arrow) extending to lamina propria. (H and E, ×64)

R, Photomicrograph of histopathologic specimen of segment of affected small bowel shows abundant gram-positive bacilli (arrow) extending to lamina propria. (Brown–Brenn, ×64).

Contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest (obtained on day 7 of illness, shortly before death) revealed perihilar parenchymal infiltrates that cause widening of the central silhouette (Fig. 1E). This may be a CT correlate of the traditional pre–CT-era description of inhalational anthrax as wide mediastinum on radiography. Compared with radiography, CT better defines the mediastinal borders (Fig. 1F); hilar adenopathy; pleural effusions, peribronchial thickening and encasement; interstitial infiltrates; and patchy air-space disease, most prominent on the right (Fig. 1F). Postmortem examination showed hilar soft-tissue perivascular and peribronchial hemorrhage (Fig. 1G) and necrosis (Fig. 1H). Special stains confirmed the presence of abundant gram-positive bacilli (Fig. 1I) consistent with B. anthracis.

CT scans obtained with mediastinal window settings showed high-attenuation subcarinal lymph nodes (Fig. 1J), consistent with hemorrhagic lymphadenitis, and mediastinal blood (Fig. 1K), consistent with hemorrhagic mediastinitis. Postmortem examination confirmed mediastinal soft-tissue hemorrhage (Fig. 1L) and hilar hemorrhagic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Fig. 1M). Special stains revealed abundant gram-positive bacilli in the hilar lymph nodes (Fig. 1N).

Abdominal CT scan (obtained concomitantly with the chest CT scan on day 7 of illness) showed ascites, mesenteric inflammation and edema, bowel wall edema, small-bowel distention with pneumatosis (Fig. 1O), and portal venous gas (Fig. 1P). On postmortem examination, an area of affected small bowel confirmed the presence of necrotizing infection with abundant neutrophils (Fig. 1Q) and gram-positive bacilli (Fig. 1R) extending to the lamina propria.

Case Report 2

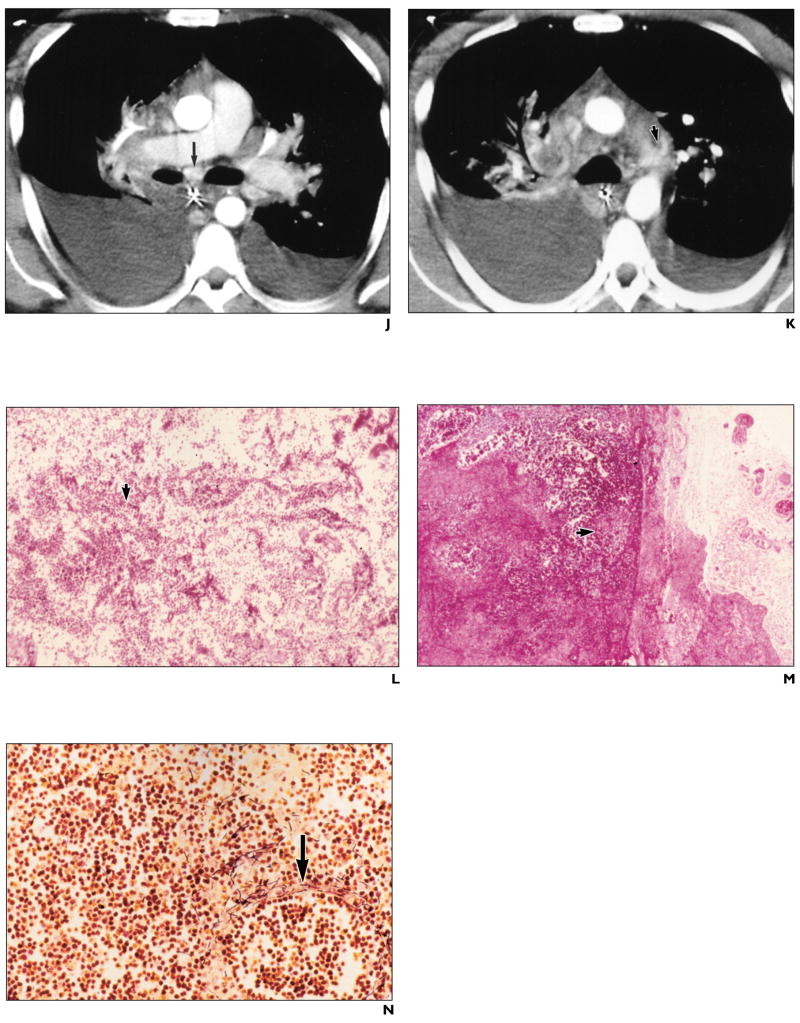

A 56-year-old woman, who worked at a mail sorting facility, developed vomiting and diarrhea on October 14, 2001. As her symptoms progressed, she developed headaches, fever, chills, mild dyspnea, and pleuritic substernal chest pain. She sought medical care 5 days later (October 19) and on arrival was in respiratory distress. A working diagnosis of inhalational anthrax was established, and she was treated with combination antimicrobial therapy. She developed large bilateral pleural effusions, which were noted to be hemorrhagic when drained. The pleural fluid was tested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and was positive for B. anthracis capsule and cell wall antigens.

A chest CT scan obtained on day 8 (October 22) of illness showed mediastinal and cervical lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2A), bibasilar infiltrates, and large pleural effusions. CT performed on day 13 (October 27) showed interval development of bibasilar parenchymal lung infiltrates (Fig. 2B) and continued pleural effusions (Fig. 2C). The imaging decompensation coincided with clinical improvement. This could be explained by a delay in the imaging evolution of findings or a second process that occurred simultaneously to resolving inhalational anthrax. Comparison of contrast-enhanced CT scans obtained on days 8 and 13 shows interval loss of enhancement within subcarinal lymph node (Figs. 2D and 2E); however, the contrast bolus timing differed between studies. Slight shrinkage with possible loss of enhancement was noted in an axillary node (Figs. 2F and 2G) after 5 days of supportive and antimicrobial therapy; however, the change could simply represent differences in contrast bolus pharmacokinetics. An enhancing adjacent axillary node apparently disappeared by day 13 (Figs. 2H and 2I); however, differing arm positions could have accounted for this change.

Fig 2. 56-year-old woman with inhalational anthrax.

A, CT scan of neck shows enlarged lymph nodes (arrow).

B and C, Contrast-enhanced CT scans show bibasilar parenchymal lung infiltrates with air bronchograms (arrow, B) and pleural effusions, developing between day 8 and day 13.

D and E, Contrast-enhanced CT scans show interval loss of enhancement within subcarinal lymph node (arrows), measuring 116 H on day 8 and 46 H on day 13, after 5 days of antimicrobial and supportive therapy.

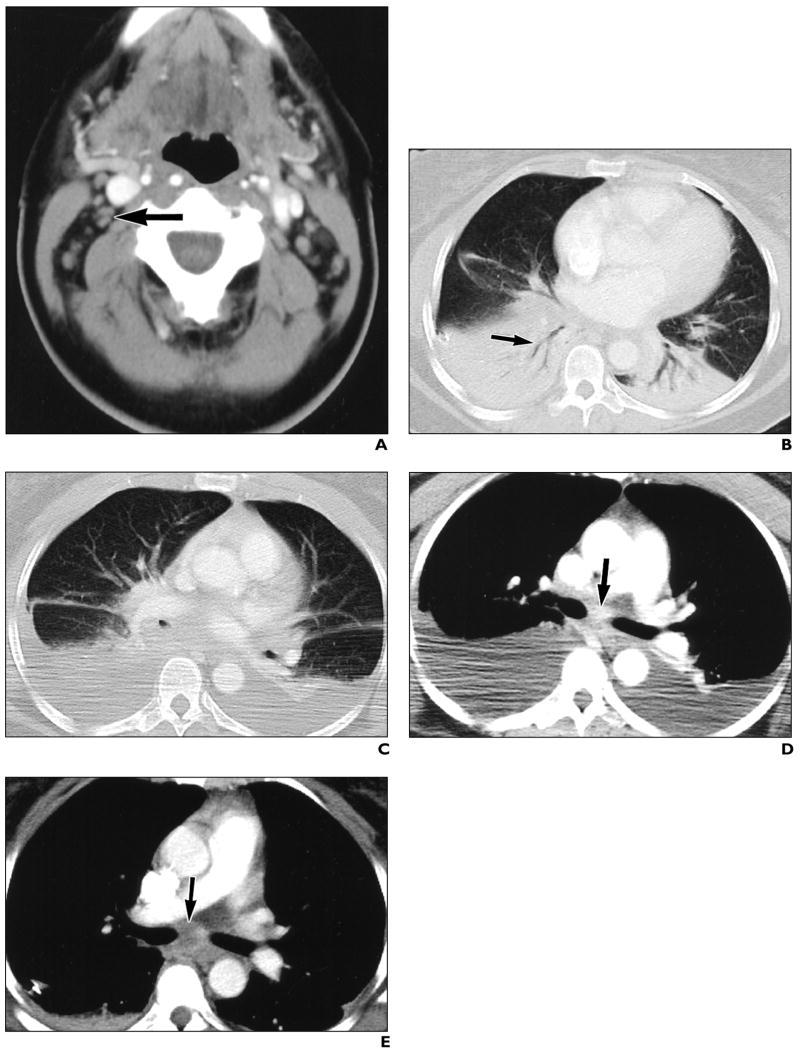

F and G, Contrast-enhanced CT scans show interval shrinkage and possible loss of enhancement within axillary lymph node (arrows), after 5 days of antimicrobial and supportive therapy. Pleural effusions have resolved after placement of chest tubes.

H and I, Contrast-enhanced CT scans of chest show interval apparent disappearance of enhancing adjacent node (arrow, H) after 5 days of antimicrobial and supportive therapy.

Discussion

Typically, the initial presentation of inhalational anthrax is nonspecific; lasts several days; and includes symptoms of fever, myalgias, and malaise. Often, unless there is a known exposure to anthrax spores, patients may not seek medical attention at this stage. If they do seek medical care, the diagnosis would not usually be entertained in the absence of known exposure because of the lack of distinguishing clinical signs and symptoms. As the disease gradually progresses into a second stage, more ominous findings of dyspnea, respiratory distress, high fever, shaking chills, and hypotension may ensue. If patients are not treated appropriately at this stage, death occurs 24–72 hr after presentation.

The limited number of reports on inhalational anthrax in the medical literature describe disease manifestations as pleural effusions, mediastinal widening, and rarely pneumonia [8–11]. Mediastinal widening has been reported to be the earliest radiographic sign [9]. In the second patient, enhancing nodes occurred in the absence of mediastinal widening or hemorrhagic mediastinitis. Nodal enhancement may be an early sign of infection, occurring even before mediastinal widening. Radiographic appearance of consolidation and air-space disease were also presenting features of inhalational anthrax in these cases. However, infectious pneumonia is found only rarely in postmortem tissue examinations. In our first patient, the infiltrates were identified as peribronchial hemorrhage because the postmortem examination did not show any evidence of infectious pneumonia. In a series of 42 autopsies from the Sverdlovsk experience in 1979, 11 cases had focal, hemorrhagic, necrotizing pneumonic lesions without a bronchoalveolar pneumonic process [1, 10, 11].

The first 10 patients from this recent bioterrorism-related outbreak had abnormal findings on chest radiographs at presentation. Eight had pleural effusions, seven had a wide mediastinum, and seven had lung infiltrates [12]. Thus, in the correct epidemiologic setting, radiologists and clinicians need to consider inhalational anthrax in the differential diagnosis of patchy air-space disease as well as widened mediastinum or bloody pleural effusions. Imaging methods, of course, may not differentiate pneumonia from hemorrhage.

Most published experience with inhalational anthrax occurred before widespread availability of CT. Mediastinal widening with high-attenuation mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes on CT in the absence of trauma, dissection, or bleeding diathesis is suspicious. In fact, this constellation of imaging features in a patient with possible exposure is almost pathognomonic for inhalational anthrax.

The loss of nodal enhancement or the disappearance of adenopathy on CT may be surrogate markers for clinical improvement. Nodal permeability may be the underlying cellular process altered by acute inhalational anthrax. The temporal–spatial factors that may influence nodal enhancement are not well understood; however, they may be related to timing of the imaging, severity of disease, and contrast pharmacokinetics (injection rate, hydration status, hemodynamics, washout into extracellular space). Nodal enhancement in our second patient was seen on day 8. Nodal enhancement without internal necrosis or hemorrhage could potentially represent improving or less severe infection. Decreased nodal enhancement has been previously reported during treatment for inhalation anthrax [13]. However, adenopathy did not resolve in days, as it may have in one node presented here. CT of enhancing nodes associated with inhalational anthrax may show differing degrees of edema and enhancement [13, 14]. Illdefined ringlike nodal enhancement has been described on 20-min delayed CT [14]. This has been postulated to be the result of nodal hemodynamics, with rapid nodal enlargement and vascular compromise.

Pneumatosis and portal venous gas have not been previously reported in association with inhalational anthrax. Bowel wall pneumatosis with portal venous gas can signify bowel ischemia or infarction and may constitute a surgical emergency in certain clinical settings [15, 16]. The abdominal features of pneumatosis, portal venous gas, ascites, and bowel wall thickening in patients with possible exposure should also alert clinicians to the possibility of inhalational anthrax. Both of these patients initially presented with gastrointestinal symptoms, and gram-positive bacilli were found in the small bowel on postmortem examination of our first patient. Abdominal CT scan may be helpful in the evaluation of this unusual presentation, but clinicians should think of ischemia before inhalational anthrax as a cause of portal venous gas, bowel wall thickening, and pneumatosis.

Gastrointestinal anthrax is considered a rare disease. It may present with nausea, vomiting, malaise, bloody diarrhea, and it may progress to acute abdominal sepsis and shock. It predominantly affects the terminal ileum or cecum [1, 11]. Both of our patients presented with gastrointestinal symptoms. However, postmortem examination (available for our first patient) did not reveal primary gastrointestinal anthrax, because no mucosal lesions or regional lymphadenitis was found. This patient’s gastrointestinal disease was most likely related to direct infection after hematogenous spread; however, bowel ischemia from sepsis, hypovolemia, or distention itself may have also been a contributing factor.

Although chest radiography may be the most cost-effective screening tool, chest CT is surely the most sensitive and specific imaging test capable of depicting the abnormal thoracic and abdominal findings of inhalational anthrax. In addition, CT may play a yet-unidentified role in the follow-up of clinical response or in the detection of gastrointestinal manifestations of inhalational anthrax. The sequence and natural history of clinical and imaging findings of inhalational anthrax have not yet been well defined. However, the CDC recommends that chest CT should be considered if findings on chest radiography are normal or uncertain and there is high clinical suspicion [17–19].

The unfortunate opportunity to document the diverse radiologic and pathologic features of inhalational anthrax has revealed a wide variety of manifestations [20]. Patient survival and outbreak control may depend on an informed and suspicious health care team, so the appropriate diagnostic tests and treatment are begun quickly and relevant public health and legal authorities can be notified.

References

- 1.Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management—Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. JAMA. 1999;281:1735–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jernigan JA, Stephens DS, Ashford DA, et al. Bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax: the first 10 cases reported in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:933–944. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush LM, Abrams BH, Beall A, Johnson CC. Index case of fatal inhalational anthrax due to bioterrorism in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1607–1610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer TA, Bersoff-Matcha S, Murphy C, et al. Clinical presentation of inhalational anthrax following bioterrorism exposure: report of 2 surviving patients. JAMA. 2001;286:2549–2553. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borio L, Frank D, Mani V, et al. Death due to bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax: report of 2 patients. JAMA. 2001;286:2554–2559. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mina B, Dym JP, Kuepper F, et al. Fatal inhalational anthrax with unknown source of exposure in a 61-year-old woman in New York City. JAMA. 2002;287:858–862. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barakat LA, Quentzel HL, Jernigan JA, et al. Fatal inhalational anthrax in a 94-year-old Connecticut woman. JAMA. 2002;287:863–868. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedlander AM, Pittman PR, Parker GW. Anthrax vaccine: evidence for safety and efficacy against inhalational anthrax. JAMA. 1999;282:2104–2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vessal K, Yeganehdoust J, Dutz W, Kohout E. Radiological changes in inhalation anthrax: a report of radiological and pathological correlation in two cases. Clin Radiol. 1975;26:471–474. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(75)80100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafazand S, Doyle R, Ruoss S, Weinacker A, Raffin TA. Inhalational anthrax: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Chest. 1999;116:1369–1376. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramova FA, Grinberg LM, Yampolskaya OV, Walker DH. Pathology of inhalational anthrax in 42 cases from the Sverdlovsk outbreak of 1979. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2291–2294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown K. Anthrax: a “sure killer” yields to medicine. Science. 2001;294:1813–1814. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earls JP, Cerva D, Jr, Berman E, et al. Inhalational anthrax after bioterrorism exposure: spectrum of imaging findings in two surviving patients. Radiology. 2002;222:305–312. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2222011830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krol CM, Uszynski M, Dillon EH, et al. Dynamic CT features of inhalational anthrax infection. AJR. 2002;178:1063–1066. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.5.1781063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faberman RS, Mayo-Smith WW. Outcome of 17 patients with portal venous gas detected by CT. AJR. 1997;169:1535–1538. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohtsubo K, Okai T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis and hepatic portal venous gas caused by mesenteric ischemia in an aged person. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:338–340. doi: 10.1007/s005350170100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clarification. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:909–919. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency Preparedness and Response Web site. [Accessed February 3, 2003]; Available at: www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/anthrax/index.asp.

- 20.Department of Radiologic Pathology–Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the American Registry of Pathology, and INOVA Fairfax Hospital. Joint Web site of Department of Radiologic Pathology–Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. [Accessed February 3, 2003]; Available at: anthrax.radpath.org/Summary2.html.