Abstract

Endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) is a constitutively expressed gene in endothelium that produces NO and is critical for vascular integrity. Previously, we reported that the 27-nucleotide (nt) repeat polymorphism in eNOS intron 4, a source of 27-nt small RNA, which inhibits eNOS expression, were associated with cardiovascular risk and expression of the eNOS gene. In the current study, we investigated the biogenesis of the intron 4-derived 27-nt small RNA. Using Northern blot, we showed that the eNOS-derived 27-nt short intronic repeat RNA (sir-RNA) expressed only in the eNOS expressing endothelial cells. Cells containing 10 × 27- or 5 × 27-nt repeats produced higher levels of 27nt sir-RNA and lower levels of eNOS mRNA than the cells with 4 × 27-nt repeats. The 27nt sir-RNA was mostly present within the endothelial nuclei. When the splicing junctions of the 27-nt repeat containing intron 4 in the full-length eNOS cDNA vector were mutated, 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis was abolished. Suppression of Drosha or Dicer diminished the biogenesis of the 27nt sir-RNA. Our study suggests that the 27nt sir-RNA derived through eNOS pre-mRNA splicing may represent a new class of small RNA. The more eNOS is transcribed or higher number of the 27-nt repeats, the more 27nt sir-RNA is produced, which functions as a negative feedback self-regulator by specifically inhibiting the host gene eNOS expression. This novel molecular model may be responsible for quantitative differences between individuals carrying different numbers of the polymorphic repeats hence the cardiovascular risk.

Endothelial-derived NO, mainly synthesized by endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS),3 has a central role in maintaining the functional integrity of endothelial cells, hemodynamic regulation, arterial wall remodeling, and establishment of collateral circulation (1). Effects of NO result either directly from reactions between NO and specific biological molecules through S-nitros(yl)ation (2), or indirectly from reactive nitrogen oxide species through oxidation (3). These direct or indirect effects can produce both physiological and pathological outcomes (4). Adequate NO production is essential for anti-atherogenic and anti-thrombotic processes in the normal arterial wall; attenuated NO bioavailability promotes vascular diseases. Reduction in basal NO release may predispose to hypertension, thrombosis, vasospasm, and atherosclerosis (5), and overproduction of NO can result in excessive oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which promote vascular diseases. Central to all these physiological functions is the proper eNOS expression and adequate eNOS enzyme activity. Over recent years, tremendous research efforts have concentrated on the regulation of eNOS enzyme activities. Comparatively, progress in molecular mechanisms regulating eNOS expression at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational levels is relatively slow.

Although functional roles of the eNOS DNA variants are not clear, hundreds of studies investigating associations between various eNOS polymorphisms and vascular diseases have been published over the last decade. This is especially so for the 27-nucleotide (nt) repeat polymorphism in the eNOS intron 4, which is highlighted by a meta-analysis of 12,990 subjects showing significant associations with vascular diseases (6). Although a recent Framingham Study reported no association between 33 single nucleotide polymorphisms in the eNOS gene and endothelial function (7), others reported positive associations between the promoter T-786C polymorphism, CA repeats in intron 13, E298D at exon 7, and endothelial function and vascular diseases (8). Studies of ours and others suggest that the 27-nt repeat polymorphism at eNOS intron 4 is likely functional in regulating eNOS expression.

Recently, we have demonstrated that: (a) the 27-nt repeats may act as an enhancer/repressor regulating eNOS expression, the effect is maintained during in vitro cell replication in endothelial cells carrying different genotypes (9, 10); (b) the 27-nt repeats in eNOS intron 4 produce 27-nt small RNA, which appears to inhibit eNOS expression at the transcriptional level (11, 12). However, the biogenesis of the intron 4-derived 27-nt small RNA is not clear. In the current study, we defined the molecular pathways for the 27-nt small RNA biogenesis, which is distinct from most known classes of small RNAs (13-16). This short intronic repeat small RNA (sir-RNA) could either be a new class of small RNA or an atypical form of the microRNA. We speculate that the intron 4-derived 27-nt small RNA may function as a negative feedback regulator and maintain the stable transcription of eNOS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents—Restriction enzymes, T4 kinase, DNA ligases, polymerases, and other molecular biology enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs (Beverly, MA) or Promega (Madison, WI). Plasmid and DNA gel purification kits were from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). All oligonucleotides were synthesized by iDNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). The mirVana miRNA Isolation kit was from Ambion, Inc. (Austin, TX). Sephadex columns for probe purification were from Roche Diagnostics Corp. Anti-eNOS antibody and anti-β-actin antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) and Sigma. Anti-Drosha and Dicer antibodies were from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Human tissue total RNAs were from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). Hybond nylon membrane and [32P]ATP were from GE Healthcare and PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Protein determinations were made with the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). All other chemicals were from Sigma.

Plasmids—We amplified the human eNOS gene from exon 3 to intron 4 (4674 to 6498 bp) or part of intron 4 (5130 to 6430) with the standard PCR technique from genomic DNA extracted from human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). We cloned the PCR products into pCR2.1-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen) re-cloned into human eNOS full-length cDNA/pCMV-2B expression vector at the ScaI site. The correct sequence and orientation of the inserts were confirmed by direct DNA sequencing. Primers with restriction enzyme site (underlined) for cloning are: sense 5′-AGTACTTACAGCTCCATTAAGAGGTGACAG-3′, antisense 5′-AGTACTCCTGAGCCAGCCGAGGCAGCGGGAGAG-3′, sense, 5′-AGTACTGGTGCGGCTGGCCAGCGACTGAGAG-3′, antisense 5′-AGTACTCCTGAGCCAGCCGAGGCAGCGGGAGAG-3′. For generation of the 10 × 27-nt construct, we carried out two separate PCR. We first amplified the DNA fragment from the 5′ end to the end of the 5th 27-nt repeat. We then amplified the DNA fragment from the beginning of the 1st 27-nt repeat to the 3′ end of the intron 4. These two DNA fragments were end-end annealed for the generation of the 10 × 27-nt fragment and inserted into the pCMV-2B-eNOS cDNA vector.

For the assessment of the independent promoter, the region (1953 bp, 4545-6498 bp) spanning from eNOS exon 3 to intron 4 was amplified from HUVEC genomics DNA. Primers with KpnI and XhoI sites were: sense 5′-GGTACCCTCGACCCAGGATGGGCCCTGCACC, antisense 5′-AGATCTCCTGAGCCAGCCGAGGCAGCGGGAGAG-3′. The PCR product was cloned into pGL3 basic vector by T4 DNA ligase at XhoI and KpnI sites. In addition, the serial deletions of the 1.5-kb region upstream of the 27-nt repeats in the eNOS intron 4 were amplified by PCR before being inserted into the pGL3 basic vector at XhoI and KpnI. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to generate the splicing-deficient constructs.

siRNA-mediated Gene-specific Suppression—Following siRNA duplexes specific for Drosha and Dicer, genes were designed to suppress the expression of Drosha and Dicer. Luciferase gene-specific siRNA was used as a negative control. The target sequences for Drosha, Dicer, and luciferase were: 5′-AACCGAAGAUCACCAUCUCUG-3′, 5′-AAUCUAUUAGCACCUUGAUGU-3′, and 5′-UCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACG-3. Before transfection with Lipofectamine 2000, formation of siRNA duplex was performed.

Cell Culture and Transfection—HeLa (human cervical epithelial cancer cell line) and 293 (human embryonic renal epithelial cell line) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cellgro, Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human skin fibroblast cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Human coronary artery smooth muscle cells were purchased from Cell Application, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Human skin fibroblasts were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium (ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human coronary artery smooth muscle cells were cultured in smooth muscle cell growth medium (Cell Applications, Inc.). Human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) were obtained from Cell Application and cultured in EBM-2 endothelial cell basic medium with Bulletkit (Cambrex, Inc., Charles City, IA) containing hydrocortisone, fibroblast growth factor B, vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, ascorbic acid, epidermal growth factor, GA-1000, heparin, and 2% fetal calf serum. Primary HUVECs were collected from human umbilical cords as described previously (10), which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine. All types of cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The siRNA duplex and plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's protocol.

Northern Blot and Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR—Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and small RNAs were isolated from the cultured cells using the mirVana miRNA Isolation kit. For Northern blots of sir-RNA, 20 μg of RNA was resolved on 15% polyacrylamide, 8 m urea gels, and electrophoresized with 130 V for 2 h at room temperature. The resolved RNAs were transferred to the positively charged Nylon membrane. The synthesized antisense 27-nt oligonucleotide probe according to the 27-nt repeat sequence in the eNOS intron 4 was 5′ end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by the T4 kinase. For eNOS mRNA detection, RNase protection assays were performed by using the RNase Protection Assay III kit from Ambion, Austin, TX, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five to 20 μg of total RNA was used per reaction. Cyclophilin antisense control template was obtained from Ambion and labeled using T7 RNA polymerase. Primer sequences for RT-PCRs were as follows: eNOS, 5′-CGAACAGCGGCTTCAAGAGGTG-3′ and 5′-CTGGATCCGGCCCACGCAGCG-3′; β-actin, 5′-AAAGACCTGTACGCCAACAC-3′ and 5′-GTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTGAT-3′. The protocol for quantitative real-time RT-PCR was the same as described previously (17).

Luciferase Assay—For luciferase assay, the cultured cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in 300 μl of cold cell lysis buffer (Promega), and lysed by vortexing with acid-washed glass beads (Sigma). One microliter of a 1:50 dilution of the lysate was added to 100 μl of luciferase assay regent (Promega), and luciferase activity was detected with a luminometer (TD-20/20 Turner Designs). Protein concentrations of crude lysates were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad) and used to normalize activity values.

Western Blot—Proteins extracted from the cultured cells were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat milk in TBS-T (50 mmol/liter Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/liter NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation with primary antibodies in TBS-T containing 5% milk overnight at 4 °C, the membrane was washed extensively with TBS-T before incubation with secondary anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After extensive washing with TBS-T, the membrane was visualized with ECL plus reagents for chemiluminescence detection (Amersham Biosciences).

Statistic Analyses—All quantitative data were presented as the mean ± S.E. of three separate experiments and compared by Student's t test for between group differences. The p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

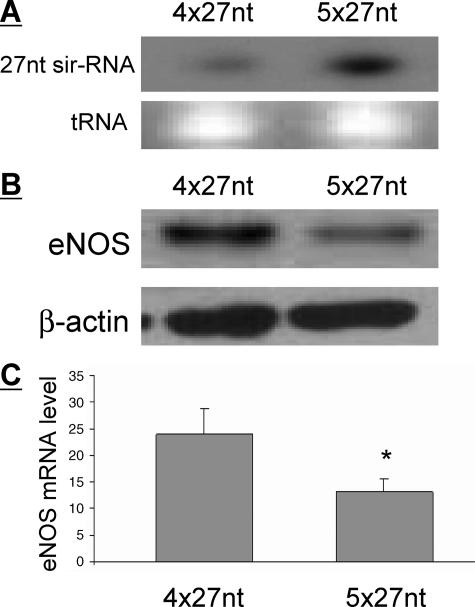

Association between the Expressions of the 27-nt sir-RNA and eNOS—Because 27nt sir-RNA is likely derived from the eNOS gene, we first evaluated the possible relationship in the expression between the two. Among the HUVECs collected from different individuals (10), we selected HUVECs with the confirmed 5 × 27-nt repeat homozygotes (n = 3) or 4 × 27-nt repeat homozygotes (n = 3) defined by PCR genotyping described earlier (10). We cultured these cells to full confluence. Total RNA and proteins were isolated from the cultured cells. Expression of 27nt sir-RNA was analyzed by Northern blot; expression of eNOS was measured by the quantitative real-time RT-PCR for mRNA and Western blot for the protein levels. As shown in Fig. 1A, HUVECs with 5 × 27-nt repeats had higher 27nt sir-RNA levels than those with 4 × 27-nt repeats (49.8 ± 3.9 versus 39.6 ± 1.6, p < 0.05). However, the levels of eNOS protein (Fig. 1B) and mRNA (Fig. 1C) were significantly reduced in HUVECs with 5 × 27-nt repeats than those with 4 × 27-nt repeats (eNOS protein: 26.1 ± 0.1 versus 40.5 ± 0.8, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of 27nt sir-RNA and eNOS in HUVECs with different numbers of 27-nt repeats in eNOS intron 4. HUVECs (4th passage) homozygous for 5 × 27-nt repeats or homozygous for 4 × 27-nt repeats in the eNOS intron 4 were cultured to full confluence before being harvested for RNA and proteinextractions.A, Northern blot for the detection of the 27 nt sir-RNA.B, Western blot analysis for the eNOS protein levels in HUVECs of either 4 × 27- or 5 × 27-nt homozygotes. C, the eNOS mRNA levels were measured by the quantitative real-time RT-PCR and their relative expression levels are shown corresponding to their genotypes. The results represent RNAs from HUVECs of three subjects of 4 × 27-nt homozygotes and three subjects of 5 × 27-nt homozygote. *, p < 0.05 by the Student's t test.

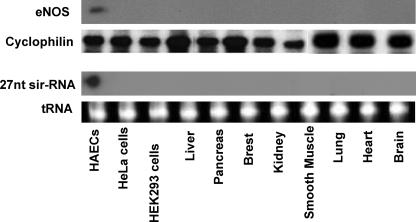

Tissue-specific Expression of the 27nt sir-RNA—To explore the cell-specific expression in the 27nt sir-RNA, we isolated or purchased total RNA from 12 different types of human cells or tissues. We measured the 27nt sir-RNA and eNOS mRNA using Northern blot. As shown in Fig. 2, the 27nt sir-RNA was only detectable in HAECs, which corresponded with the expression of eNOS mRNA.

FIGURE 2.

Tissue-specific expression of 27nt sir-RNA. Total RNAs (10 μg/lane) were either extracted from the cultured HAECs, HeLa cells, HEK293 cells (lanes 1-3), or purchased from Clontech (lanes 4-11). The RNA samples were electrophoresized on the 1% acrylamide, 8 m urea gel and analyzed by Northern blot for eNOS mRNA using the exon 4-specific mRNA probe (top lane) and cyclophilin was used as the control, or 15% acrylamide, 8 m urea gel detected with 32P-labeled 27-nt antisense oligonucleotide probe for the 27nt sir-RNA (lower panel). The same membrane was also hybridized with a 5.8 S rRNA probe as the gel loading control (bottom lane).

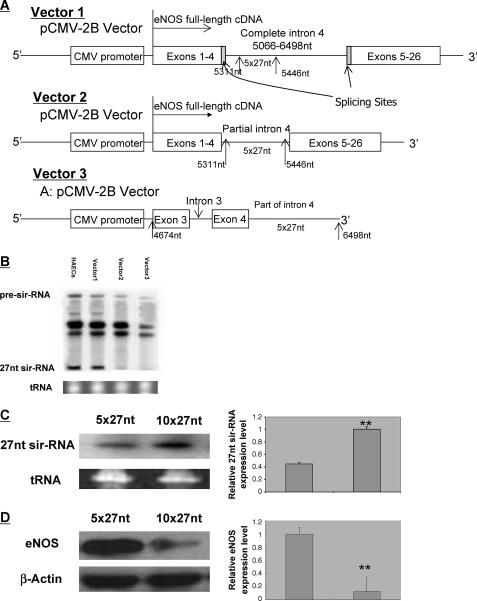

Expression of the 27nt sir-RNA by the eNOS cDNA-Intron 4 Constructs—Because the 27nt sir-RNA is co-expressed with the eNOS, we designed experiments to investigate the mechanisms responsible for 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis. We generated three constructs as outlined in Fig. 3A. These constructs were built based on the pCMV-2B-eNOS full-length cDNA plasmid generated in our laboratory (18, 19). In Vector 1, the DNA fragment containing the entire intron 4 sequence was inserted. To not disrupt the eNOS coding cDNA, we selected the ScaI site and the insert contained the sequence from part of exon 3 to the entire intron 4 (4674 to 6498 bp) with the ScaI adaptor added at both ends. The vectors with correct sequence and orientation determined by the direct sequencing were selected for the study. Intron 4 spans from 5006 to 6498 bp; the 5 × 27-nt repeat containing the region starts at 5331 to 5446 bp. Vector 2 contained only a part of intron 4 (5130 to 6430 bp), which includes 5 × 27-nt repeats but with intron 4 splicing junctions at 5′ and 3′ ends being removed. Vector 3 had no eNOS cDNA but has the cloned segment of 4674 to 6498 bp inserted at the 3′ end of the vector CMV promoter. All three constructs were then transfected into HeLa cells. We chose HeLa as the host cells because they have the necessary eNOS expression machineries but without endogenous 27nt sir-RNA (11, 12). Total RNA was extracted 48 h after transfection; 27nt sir-RNA was measured by Northern blot using 32P-labeled 27-nt oligonucleotide probe. As shown in Fig. 3B, only Vector 1, which contains the full-length eNOS cDNA and complete intron 4 with 5′ and 3′ splicing junctions intact, produced the 27nt sir-RNA similarly as the HAECs. Removal of splicing junctions in Vector 2 abolished the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis. This suggests that a splicing process similar to eNOS pre-mRNA splicing may be required for the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis. Lack of 27nt sir-RNA production in Vector 3 indicates that DNA sequences up to exon 3 upstream of 27-nt repeats are not sufficient to drive the expression of the 27nt sir-RNA.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic illustration of the vectors constructed to investigate DNA sequences essential for 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis. A, all constructs were based on the pCMV-2B-eNOS full-length cDNA vector. Clones with the correct orientation confirmed by direct sequencing were selected for the study. Vector 1 contains a full-length eNOS intron 4 (5066-6498 bp). To insert the full intron 4 without disrupting the eNOS cDNA codes, we cloned 1824-bp DNA from 4674-6498 bp using DNA from HUVECs with the 5 × 27-nt repeat genotype. Selection of this fragment was based on the ScaI restriction site on the eNOS full-length cDNA in the vector and starts from part of exon 3 to intron 4. Vector 2 contains only part of intron 4 (5130-6430 nt) but the full sequence of the 5 × 27-nt repeats. This insert eliminated the splicing junctions at both 5′ and 3′ ends flanking intron 4. Vector 3 was generated from the pCMV-2B vector with only intron 4 containing the DNA fragment (4674-6498 bp) to test whether 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis can be driven from an independent promoter. B, 48 h after the vectors were transfected to the HeLa cells, RNA was extracted from the transfected and non-transfected cells; Northern blot was carried out for detection of the 27-nt sir-RNA using 32P-labeled 27-nt oligonucleotide probe. The 27-nt sir-RNA was only detectable in HeLa cells transfected with Vector 1, which contains the entire intron 4 with both splicing junctions intact. In the meantime, the 27-nt probe also detected the presence of a pre-sir-RNA band sized ∼150 nt in both HAECs and cells transfected with Vector 1. The presence of the band was weaker in cells transfected with Vectors 2 and 3. RNA from non-transfected HeLa cells was the negative control and HAECs was the positive control. We have noted two prominent bands at the position between the pre-sir-RNA and 27nt sir-RNA with sizes estimated around 70 and 80 nt. Although they could be the intermediate products in the process of the pre-sir-RNA to mature 27nt sir-RNA transformation, they could also be nonspecific bands. The origin and functional relevance of these additional bands will need to be investigated further. The tRNA stained with EtBr was used as the loading control. C, to further investigate the dose-dependent effect, we generated DNA fragment containing 10 × 27-nt repeats based on the 4674-6498-bp DNA fragment. We first amplified the DNA fragment from the 5′ end to the end of the 5th 27-nt repeat. We then amplified the DNA fragment from the beginning of the 1st 27-nt repeat to the 3′ end of the intron 4. These two DNA fragments were end-end annealed for the generation of the 10 × 27-nt fragment and inserted into the pCMV-2B-eNOS cDNA vector. Only vectors with the correct sequence and orientation confirmed by the direct sequencing were selected for the study. The constructs were then transfected to HeLa cells. After 48 h, RNA was extracted for the Northern blot to detect 27nt sir-RNA. The left two lanes show the 27nt sir-RNA from Vector 1 containing 5 × 27-nt repeats; the right two lanes show the 27nt sir-RNA from the vector containing 10 × 27-nt repeats. The tRNA was illustrated as the loading control. D, to explore whether the overexpressed 27-nt RNA could suppress host cell eNOS expression, we transfected the vectors to HAECs and Western blot was used to examine the eNOS protein expression. Cells transfected with the 5 × 27-nt vector had significantly more eNOS expressed than the cells transfected with the 10 × 27-nt vector.

To further evaluate the relationship between the numbers of the 27-nt repeats and the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis, we generated the pCMV-eNOS cDNA-intron 4 construct containing 10 × 27-nt repeats based on the design of Vector 1. We transfected the vectors containing either 5 × 27- or 10 × 27-nt repeats into HeLa cells and HAEC total RNA and the protein were extracted 48 h post-transfection. Fig. 3C (upper panel) shows the 27nt sir-RNA in transfection HeLa cells by Northern blot. The 10 × 27-nt repeat construct produced significantly more 27nt sir-RNA (70.3 ± 0.5) than those of the 5 × 27-nt construct (32.9 ± 2.8, p < 0.05). To investigate whether the overexpressed 27-nt RNA suppressed the host cell eNOS expression, we further transfected these two vectors to HAECs. The eNOS expression by Western blot in HAECs transfected with the 10 × 27-nt construct had significantly lower eNOS protein than those transfected with the 5 × 27-nt construct (eNOS protein: 9.6 ± 0.2 versus 80.3 ± 0.4, p < 0.01).

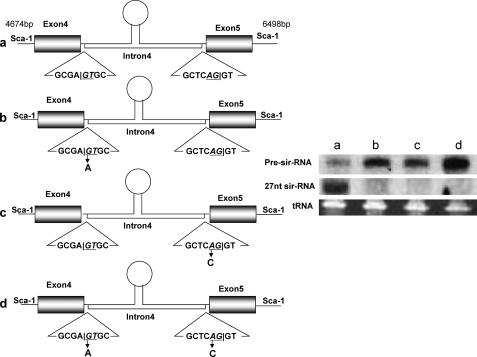

Role of eNOS Pre-mRNA Splicing in 27nt sir-RNA Biogenesis—Because deletion analysis showed that splicing junctions of intron 4 were essential for the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis, we further investigated the role of eNOS pre-mRNA splicing in 27nt sir-RNA production by mutating the nucleotides in the splicing junctions. Fig. 4 shows the schematic design of the mutagenesis at the 5′ end GCGA|GTGC and 3′ end GCTCAG|GT splice junctions of the eNOS intron 4. Vector 1 as described in the legend to Fig. 3 was used as the template for mutagenesis. We designed two pairs of specific mutation primers to introduce a mutation at the 5′ end from GT to AT, and at the 3′ end from AG to CG. Vector-a is the wild-type control; Vector-b contains a mutation at the 5′ end; Vector-c contains a mutation at the 3′ end; Vector-d contains mutations at both 5′ and 3′ ends. Forty-eight hours after transfection of these constructs to the HeLa cells, total RNA was extracted for 27nt sir-RNA detection. As shown in Fig. 4, mutations at either splicing junction of intron 4 abolished the biogenesis of the 27nt sir-RNA, and caused accumulation of specific pre-sir-RNA sized ∼150 nt.

FIGURE 4.

Schematic illustration of mutagenesis at the 5′ and 3′ splicing sites flanking the eNOS intron 4. Based on Vector 1 described in the legend to Fig. 3A, we carried out mutagenesis to create the GT → AT mutation at the 5′ end junction GCGA|GTGC (b), or AG → CG mutation at the 3′ end junction GCTCAG|GT (c), or both (d). These vectors with or without mutations at intron 4 splicing sites were transfected to HeLa cells for 48 h before RNA was extracted for 27nt sir-RNA analysis. As shown in the Northern blot panel, only the vector with wild-type splicing junctions produced 27nt sir-RNA. Mutations at either site abolished 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis, and resulted in the accumulation of specific pre-sir-RNA (lanes b-d). The loop is drawn to indicate the possible existence of a secondary structure rather than to suggest any specific type of secondary structure.

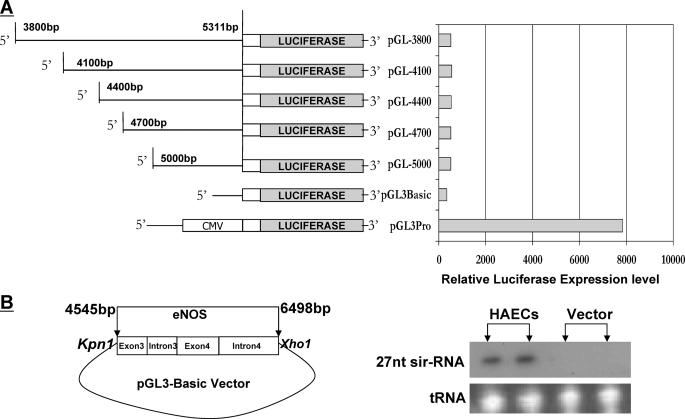

Possibility of an Independent Promoter Drives 27nt sir-RNA Expression—To study the possibility that an independent promoter may be responsible for the expression of 27nt sir-RNA, we first prepared serial deletion reporter constructs by cloning the 5′-flanking sequence 1.5-kb upstream of the 27-nt repeats at eNOS intron 4 into the luciferase reporter vectors (Fig. 5A), which were then transfected to HeLa cells. At 48 h post-transfection, we measured luciferase activity and luciferase mRNA levels. Our experiment showed no promoter activity of this region. To investigate the possibility that the luciferase reporter vector coding regions for transcription and translation may not be suitable to study the function of the promoter that drives the small RNA expression, we further cloned 766 bp upstream of the 27-nt repeats together with the entire eNOS intron 4 into the pGL3-basic vector at the KpnI and XhoI sites (Fig. 5B). As shown in Fig. 5B, the construct produced no 27nt sir-RNA, which suggests no independent promoter exists for the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis, at least not within the 766-bp upstream region.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic representation of the pGL3 clones with 5′ serial deletions of the 1.5 kb upstream of the 27-nt repeats in eNOS intron 4 and their transcriptional activities. A, HeLa cells were transfected with pGL3-promoter constructs containing serially deleted 1.5-kb DNA fragments upstream of the 27-nt repeats in eNOS intron 4. The relative luciferase activities were assessed. The protein extract from HeLa cells transfected with the pGL3-basic vector was used as the negative control, and pGL3-promoter as the positive control. The data were normalized to the activity of the co-transfected pSV galactosidase plasmid. B, because functional features of the promoter for small RNA transcription may be different from regular promoters that drive protein coding genes, we further built a construct by cloning the DNA fragment containing 766 bp upstream of the 27-nt repeats and the entire intron 4 (4545-6498 bp) into the pGL3 basic vector at KpnI and XhoI cloning sites. Forty-eight hours after transfection to the HeLa cells, RNA was extracted for 27nt sir-RNA detection. The right two lanes were positive controls from HAECs and the left two lanes was the RNAs from HeLa cells transfected with the construct showing that no 27nt sir-RNA was produced by the construct.

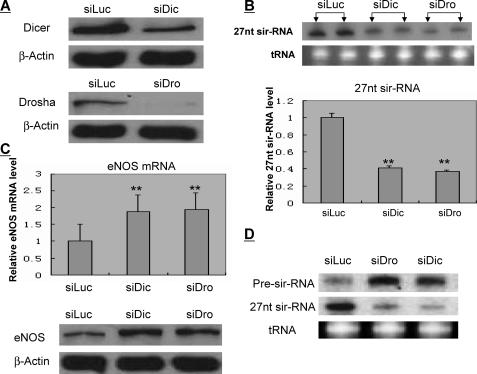

Relevance of MicroRNA Processing Machinery in the 27nt sir-RNA Biogenesis—We next examined the relevance of common processing machineries for small RNAs in the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis. It has generally been assumed that RNase type III Drosha is responsible for the nuclear small RNA, particularly miRNA, process to produce precursor miRNA. Pre-miRNAs are then exported to the cytoplasm by exportin 5 and processed into miRNA duplexes through the action of the cytoplasmic type III RNase Dicer. To study whether Dicer or Drosha is also involved in 27nt sir-RNA processing, we suppressed the expression of Dicer or Drosha by transfecting Drosha- or Dicer-specific siRNA to HAECs (Fig. 6A). Total RNA was extracted 48 h after transfection and subjected to Northern blot for 27nt sir-RNA detection. We showed that repression of Drosha or Dicer resulted in significant reduction in the 27nt sir-RNA expression (Fig. 6B). The reduced 27nt sir-RNA corresponded with increased host gene eNOS expression (Fig. 6C). In the same RNA extracts, which were extracted 24 h after the respective Drosha- or Dicer-specific siRNA treatment, we also found that whereas the Dicer or Drosha knockdown reduced the expression of 27nt sir-RNA, the 27-nt specific pre-sir-RNA was accumulated (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 6.

Bioprocess of the 27-nt sir-RNA. To explore the bioprocess of the 27nt sir-RNA, we transfected the HAECs with the gene-specific siRNAs for Drosha (siDro) and Dicer (siDic), which are known for cytoplasmic and nuclear small RNA processing. The siRNA specific to the luciferase gene was used as the control. Forty-eight hours after transfection, RNA and proteins were extracted from the transfected endothelial cells. A, Western blots for protein levels of Dicer or Drosher in endothelial cells treated with siDro or siDic. β-Actin was used as the internal control. B, Northern blot for the 27nt sir-RNA. There was a significant reduction in the amount of 27nt sir-RNA from cells when the Dicer or Drosha genes were suppressed. Using the densitometry scan, the experiments showed that the amount of the 27nt sir-RNA in Dicer- or Drosha-suppressed endothelial cells were 41.3 ± 2.9 and 37.4 ± 1.6% of the levels in the control cells, respectively. Columns in the bar chart represent mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 between the treated and the control by the Student's t tests. C, top panel shows the host gene eNOS mRNA levels as measured by the quantitative real-time RT-PCR were increased in endothelial cells with Dicer or Drosha suppressed (1.81 ± 0.22 and 1.93 ± 0.23%, respectively). The lower panel shows Western blot of eNOS proteins in endothelial cells treated with Dicer- or Drosha-specific siRNAs. D, expression of 27nt sir-RNA was reduced significantly in cells with Drosha or Dicer knockdown. This reduction is accompanied by the simultaneous increase in the accumulation of pre-sir-RNA sized ∼150 nt. tRNA is used as the loading control.

DISCUSSION

Although we have attempted to classify this intronic repeat-derived small RNA as a miRNA (11), most features in biogenesis, processing, and possible mechanisms of effects on target genes do not meet the criteria as a classical miRNA. Our current study suggests that 27nt sir-RNA is derived from the 27-nt repeat sequence in eNOS intron 4 through the eNOS pre-mRNA splicing. The more the number of 27-nt repeats, the more the 27nt sir-RNA is produced. This association is biologically significant because the number of 27-nt repeats in eNOS intron 4 is reported to be associated with risk of myocardial infarction, especially in smokers (20). We further discovered that nuclear actin tended to bind to the 27-nt repeat element and partially attenuate the 27-nt RNA-mediated eNOS suppression (12).

Currently, several types of small RNAs have been described: miRNA, piwiRNA (21), siRNA, tiny noncoding RNA, heterochromatic siRNAs, and repeat-associated small RNAs in plants and animals (22, 23). Some of these small RNAs could be present only during the developmental stage or be responsible for tissue-specific expressions (23). These small RNAs typically are ∼21-25 nt in length; longer ones are mostly from repeat-associated small RNAs (23). Although siRNAs are typically from an exogenous source or during virus infection, miRNAs are mainly transcribed through designated genomic sequences (24). In some cases, the miRNAs can also be derived from transcribed introns spliced during the nuclear pre-mRNA process (14, 25). There is a clear definition for what qualifies as miRNA, which is a distinct ∼22-nt RNA transcript detected by Northern blot. Biogenesis criteria include existence of 50-80-nt pre-miRNA stem-loops to be processed by the Microprocessor complex of nucleases and associated factors, including the RNase III Drosha and its partner DGCR8/Pasha within the nucleus (26). Through exportin-5, the pre-miRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm and processed by Dicer to become mature miRNAs, which will stay in the cytoplasm to either induce target mRNA degradation or directly inhibit translation (24). Contrary to siRNA, which requires a perfect sequence match and initiates gene-specific inhibition, miRNA does not require a perfect match of the target mRNA and can regulate more than 200 target mRNAs (27). A recent description of intronic microRNA pre-miRNAs (mirtrons) was reported (28, 29), which bears the closest resemblance to the sir-RNA we discovered. Unlike the classical miRNA, the biogenesis of mirtrons is processed without the involvement of Drosha-mediated cleavage.

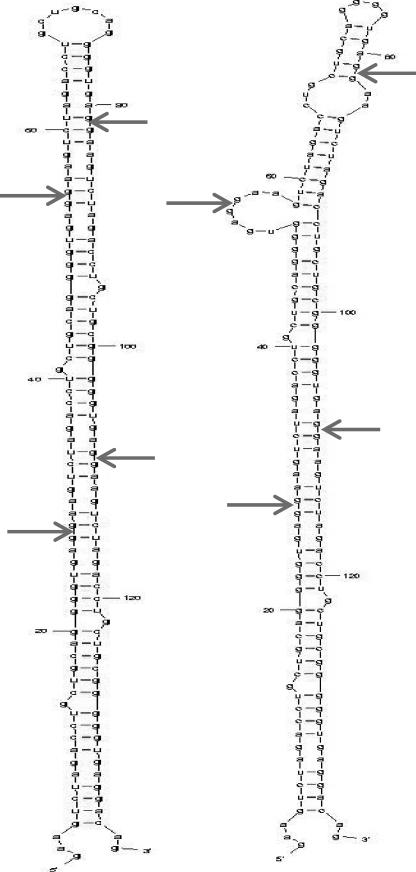

Nevertheless, our 27-nt small RNA has the following biological features, which are somehow distinct from most existing small RNAs. They include the exclusive nuclear presence of the 27nt sir-RNA, which is derived from the intronic repeat sequence (11, 12). It appears only specifically inhibiting the host eNOS gene rather than several hundred unrelated genes (11). The regulatory target stays within the nucleus by regulating eNOS gene transcription or pre-mRNA splicing directly. Using the RNA mfold web server, several stem-loop structures can be modeled with the 5 × 27-nt repeat sequence. Fig. 7 shows two examples of the modeling by including only the 27-nt repeat sequence. However, it is not clear how multiple copies of the 27-nt RNA can be cleaved from the repeat sequence of the single stem-loop structure. Our experiments have clearly shown that the number of 27-nt repeats is linearly associated with the amount of 27nt sir-RNA. These biological features suggest that our 27-nt small RNA is either a new class of small RNA, i.e. sir-RNA, or an atypical form of the existing miRNA or mirtrons. However, the fact that Dicer suppression led to decreased 27nt sir-RNA expression suggests that the cytoplasmic process may also be involved. This finding is somewhat inconsistent with the fact of the exclusive nuclear presence of the 27nt sir-RNA. It is possible that the effect of Dicer suppression on the 27nt sir-RNA is an indirect one. It is also possible that protein knockdown did not translate to functional knockdown in which the observed findings are not direct relationships between Drosha and 27nt sir-RNA or Dicer and 27nt sir-RNA. Alternatively, the 27nt sir-RNA biogenesis indeed involves a cytoplasmic process although this appears to be biologically redundant because the 27nt sir-RNA is derived from the nucleus and functions within the nucleus. One of the underlying assumptions in our experiments is that the sequence of the 27-nt sir-RNA is unique and exactly equivalent to the 27-nt intron 4 repeat sequence. However, this may not be exactly correct. The observed 27nt sir-RNA may be a family of closely related sequences. More experiments are clearly needed to resolve these issues.

FIGURE 7.

Stem-loop structure of the 5 × 27-nt repeat sequence. We subjected the whole 5 × 27-nt repeat RNA sequence (5′-GAAGUCUAGACCUGCUGCGGGGGUGAG-3′) to secondary structure modeling using the RNA mfold web server. Several stem-loop structures can be modeled with the 5 × 27-nt repeat sequence and we have presented two as examples, in which the end of 27 nt is indicated by the red arrow. Stem-loop structure has been recognized as the common secondary structure in small RNA processing. If DNA sequences flanking the 5 × 27-nt sequence are included in the modeling process, several different secondary stem-loop structures can be modeled.

With the genome-wide existence of similar short intronic repeat sequence (30, 31), we predict that this class of small RNA may function as a gene-specific negative feedback regulator. With varying numbers of the repeats between individuals, the sir-RNA based regulation could be responsible for individual differences in phenotypic expression, hence disease susceptibility. The more the host gene is transcribed, the more gene-specific sir-RNA will be produced, which forms a negative feedback regulatory loop to fine-tune the host gene expression. Variable numbers of the polymorphic repeats in populations will be responsible for quantitative individual differences in the expressed genes. More specifically, the 27-nt repeats in eNOS intron 4 can be converted to 27nt sir-RNA and functions as a negative feedback regulator of eNOS expression. Individuals with different numbers of 27-nt repeats will have different levels of 27nt sir-RNA, which is responsible for individual differences in eNOS expression, hence susceptibility to vascular diseases.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health NHLBI Grants R01HL071608, R01HL066053, and P50HL083794 (to X. L. W.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Grants 0440001N and 0565134Y (to X. L. W.) and National 973 Research Project Grant 2006CB503803 (to C. Z.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: eNOS, endothelial nitric-oxide synthase; nt, nucleotide(s); sir-RNA, short intronic repeat small RNA; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cells; miRNA, micro-RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; RT, reverse transcriptase; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

References

- 1.Gibbons, G. H., and Dzau, V. J. (1994) N. Engl. J. Med. 330 1431-1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melino, G., Bernassola, F., Knight, R. A., Corasaniti, M. T., Nistico, G., and Finazzi-Agro, A. (1997) Nature 388 432-433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckman, J. S., and Koppenol, W. H. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271 C1424-C1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausladen, A., and Stamler, J. S. (1999) Methods Enzymol. 300 389-395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oemar, B. S., Tschudi, M. R., Godoy, N., Brovkovich, V., Malinski, T., and Luscher, T. F. (1998) Circulation 97 2494-2498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casas, J. P., Bautista, L. E., Humphries, S. E., and Hingorani, A. D. (2004) Circulation 109 1359-1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kathiresan, S., Larson, M. G., Vasan, R. S., Guo, C. Y., Vita, J. A., Mitchell, G. F., Keyes, M. J., Newton-Cheh, C., Musone, S. L., Lochner, A. L., Drake, J. A., Levy, D., O'Donnell, C. J., Hirschhorn, J. N., and Benjamin, E. J. (2005) Circulation 112 1419-1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, X. L., and Wang, J. (2000) Mol. Genet. Metab. 70 241-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang, J., Dudley, D., and Wang, X. L. (2002) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22 e1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senthil, D., Raveendran, M., Shen, Y. H., Utama, B., Dudley, D., Wang, J., and Wang, X. L. (2005) DNA Cell Biol. 24 218-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, M. X., Ou, H., Shen, Y. H., Wang, J., Coselli, J., and Wang, X. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 16967-16972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou, H., Shen, Y. H., Utama, B., Wang, J., Wang, X., Coselli, J., and Wang, X. L. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 2509-2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambros, V. (2004) Nature 431 350-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng, Y. (2006) Oncogene 25 6156-6162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartel, D. P. (2004) Cell 116 281-297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rana, T. M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8 23-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, J., Jin, X., Fang, S., Wang, R., Li, Y., Wang, N., Guo, W., Wang, Y., Wen, D., Wei, L., Dong, Z., and Kuang, G. (2005) Carcinogenesis 26 1748-1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gan, Y., Shen, Y. H., Wang, J., Wang, X., Utama, B., and Wang, X. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 16467-16475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gan, Y., Shen, Y. H., Utama, B., Wang, J., Coselli, J., and Wang, X. L. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 340 29-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, X. L., Sim, A. S., Badenhop, R. F., McCredie, R. M., and Wilcken, D. E. (1996) Nat. Med. 2 41-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aravin, A., Gaidatzis, D., Pfeffer, S., Lagos-Quintana, M., Landgraf, P., Iovino, N., Morris, P., Brownstein, M. J., Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S., Nakano, T., Chien, M., Russo, J. J., Ju, J., Sheridan, R., Sander, C., Zavolan, M., and Tuschl, T. (2006) Nature 442 203-207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ambros, V., Lee, R. C., Lavanway, A., Williams, P. T., and Jewell, D. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13 807-818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aravin, A. A., Lagos-Quintana, M., Yalcin, A., Zavolan, M., Marks, D., Snyder, B., Gaasterland, T., Meyer, J., and Tuschl, T. (2003) Dev. Cell 5 337-350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen, B. R. (2004) Virus Res. 102 3-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, Y. K., and Kim, V. N. (2007) EMBO J. 26 775-783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng, Y., and Cullen, B. R. (2006) Methods Mol. Biol. 342 49-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajewsky, N. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38 Suppl. 1, S8-S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruby, J. G., Jan, C. H., and Bartel, D. P. (2007) Nature 448 83-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berezikov, E., Chung, W. J., Willis, J., Cuppen, E., and Lai, E. C. (2007) Mol. Cell 28 328-336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett, E. A., Coleman, L. E., Tsui, C., Pittard, W. S., and Devine, S. E. (2004) Genetics 168 933-951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lander, E. S., Linton, L. M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M. C., Baldwin, J., Devon, K., Dewar, K., Doyle, M., FitzHugh, W., Funke, R., Gage, D., Harris, K., Heaford, A., Howland, J., Kann, L., Lehoczky, J., LeVine, R., McEwan, P., McKernan, K., Meldrim, J., Mesirov, J. P., Miranda, C., Morris, W., Naylor, J., Raymond, C., Rosetti, M., Santos, R., Sheridan, A., Sougnez, C., Stange-Thomann, N., Stojanovic, N., Subramanian, A., Wyman, D., Rogers, J., Sulston, J., Ainscough, R., Beck, S., Bentley, D., Burton, J., Clee, C., Carter, N., Coulson, A., Deadman, R., Deloukas, P., Dunham, A., Dunham, I., Durbin, R., French, L., Grafham, D., Gregory, S., Hubbard, T., Humphray, S., Hunt, A., Jones, M., Lloyd, C., McMurray, A., Matthews, L., Mercer, S., Milne, S., Mullikin, J. C., Mungall, A., Plumb, R., Ross, M., Shownkeen, R., Sims, S., Waterston, R. H., Wilson, R. K., Hillier, L. W., McPherson, J. D., Marra, M. A., Mardis, E. R., Fulton, L. A., Chinwalla, A. T., Pepin, K. H., Gish, W. R., Chissoe, S. L., Wendl, M. C., Delehaunty, K. D., Miner, T. L., Delehaunty, A., Kramer, J. B., Cook, L. L., Fulton, R. S., Johnson, D. L., Minx, P. J., Clifton, S. W., Hawkins, T., Branscomb, E., Predki, P., Richardson, P., Wenning, S., Slezak, T., Doggett, N., Cheng, J. F., Olsen, A., Lucas, S., Elkin, C., Uberbacher, E., Frazier, M., Gibbs, R. A., Muzny, D. M., Scherer, S. E., Bouck, J. B., Sodergren, E. J., Worley, K. C., Rives, C. M., Gorrell, J. H., Metzker, M. L., Naylor, S. L., Kucherlapati, R. S., Nelson, D. L., Weinstock, G. M., Sakaki, Y., Fujiyama, A., Hattori, M., Yada, T., Toyoda, A., Itoh, T., Kawagoe, C., Watanabe, H., Totoki, Y., Taylor, T., Weissenbach, J., Heilig, R., Saurin, W., Artiguenave, F., Brottier, P., Bruls, T., Pelletier, E., Robert, C., Wincker, P., Smith, D. R., Doucette-Stamm, L., Rubenfield, M., Weinstock, K., Lee, H. M., Dubois, J., Rosenthal, A., Platzer, M., Nyakatura, G., Taudien, S., Rump, A., Yang, H., Yu, J., Wang, J., Huang, G., Gu, J., Hood, L., Rowen, L., Madan, A., Qin, S., Davis, R. W., Federspiel, N. A., Abola, A. P., Proctor, M. J., Myers, R. M., Schmutz, J., Dickson, M., Grimwood, J., Cox, D. R., Olson, M. V., Kaul, R., Shimizu, N., Kawasaki, K., Minoshima, S., Evans, G. A., Athanasiou, M., Schultz, R., Roe, B. A., Chen, F., Pan, H., Ramser, J., Lehrach, H., Reinhardt, R., McCombie, W. R., de la Bastide, M., Dedhia, N., Blocker, H., Hornischer, K., Nordsiek, G., Agarwala, R., Aravind, L., Bailey, J. A., Bateman, A., Batzoglou, S., Birney, E., Bork, P., Brown, D. G., Burge, C. B., Cerutti, L., Chen, H. C., Church, D., Clamp, M., Copley, R. R., Doerks, T., Eddy, S. R., Eichler, E. E., Furey, T. S., Galagan, J., Gilbert, J. G., Harmon, C., Hayashizaki, Y., Haussler, D., Hermjakob, H., Hokamp, K., Jang, W., Johnson, L. S., Jones, T. A., Kasif, S., Kaspryzk, A., Kennedy, S., Kent, W. J., Kitts, P., Koonin, E. V., Korf, I., Kulp, D., Lancet, D., Lowe, T. M., McLysaght, A., Mikkelsen, T., Moran, J. V., Mulder, N., Pollara, V. J., Ponting, C. P., Schuler, G., Schultz, J., Slater, G., Smit, A. F., Stupka, E., Szustakowski, J., Thierry-Mieg, D., Thierry-Mieg, J., Wagner, L., Wallis, J., Wheeler, R., Williams, A., Wolf, Y. I., Wolfe, K. H., Yang, S. P., Yeh, R. F., Collins, F., Guyer, M. S., Peterson, J., Felsenfeld, A., Wetterstrand, K. A., Patrinos, A., Morgan, M. J., de Jong, P., Catanese, J. J., Osoegawa, K., Shizuya, H., Choi, S., and Chen, Y. J. (2001) Nature 409 860-92111237011 [Google Scholar]