Abstract

Establishment of cell polarity is important for a wide range of biological processes, from asymmetric cell growth in budding yeast to neurite formation in neurons. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the small GTPase Cdc42 controls polarized actin organization and exocytosis toward the bud. Gic2, a Cdc42 effector, is targeted to the bud tip and plays an important role in early bud formation. The GTP-bound Cdc42 interacts with Gic2 through the Cdc42/Rac interactive binding domain located at the N terminus of Gic2 and activates Gic2 during bud emergence. Here we identify a polybasic region in Gic2 adjacent to the Cdc42/Rac interactive binding domain that directly interacts with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in the plasma membrane. We demonstrate that this interaction is necessary for the polarized localization of Gic2 to the bud tip and is important for the function of Gic2 in cell polarization. We propose that phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and Cdc42 act in concert to regulate polarized localization and function of Gic2 during polarized cell growth in the budding yeast.

Generation of cell polarity is critical for many basic cellular functions such as nutrient transport across epithelial cells and neuronal transmission in neurons. Cell polarization generally occurs by the delivery of proteins and lipids to specific sites on the plasma membrane (PM),4 thus generating distinct cellular domains. Budding yeast is an excellent model organism for the study of cell polarity because polarized actin organization and membrane traffic are important for bud formation and major proteins involved in cell polarization are conserved in higher eukaryotes (1–3). Cdc42, a member of the Rho family of small GTP-binding proteins and a master regulator of cell polarity, controls polarized organization of actin cables and the exocytosis machinery for bud emergence and enlargement (3, 4). Gic2, and its homolog, Gic1, are a pair of Cdc42 effectors that each contain an N-terminal Cdc42/Rac Interactive Binding (CRIB) domain, which interacts with GTP-bound Cdc42 (5, 6). Deletion of GIC1 and GIC2 together, but not either one alone, causes cells to arrest in large, round, and unbudded morphologies at 37 °C, indicative of the loss of cell polarity (5, 6). Gic2 is localized to the site of bud emergence and at tips of small buds in yeast and is required for polarized actin organization during budding at 37 °C (5, 6). Gic2 is thought to function in polarized growth by linking activated Cdc42 to proteins that regulate actin organization, such as Bni1, Spa2, and Bud6 (7). Recently, it was shown that Gic1 and Gic2 are also involved in the recruitment of septins to the presumptive bud site at the beginning of the cell cycle (8). Gic1 and Gic2 have overlapping functions, as cells that have lost either Gic1 or Gic2 are mostly normal in morphology and growth whereas cells that have lost both Gic proteins have morphological defects (including defects in actin polarization) as well as a severe growth defect at 37 °C (5, 6). Gic2 is expressed in a cell cycle-dependent manner with its expression peaking during bud emergence, and Gic2 is degraded shortly after bud emergence via ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (7, 9). Binding of Gic2 to GTP-Cdc42 is a prerequisite for degradation, suggesting that Gic2 levels are down-regulated after Gic2 fulfills its role in cell polarization (9).

Here we report that Gic2 directly interacts with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) on the PM. We have identified a polybasic region within the N terminus of Gic2 that mediates this interaction. Mutations in this domain or depletion of PI(4,5)P2 from the PM disrupted the polarized localization of Gic2 in the buds. Further genetic and cell biological analyses demonstrated that the PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc42 function in concert to control the function of Gic2 as a regulator of polarized cell growth.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Yeast Strains—Standard methods were used for yeast medium and genetic manipulations (10). All the major strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Mutagenesis on Gic2-GFP (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP) was performed using the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and verified by nucleotide sequencing. Various gic2 N-terminal (gic2NT) mutants were generated from a GIC2 2μ plasmid by PCR using different mutagenesis primers and subcloned into the centromere-based p415TEF vector (11).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strains | Genotype |

|---|---|

| 352-15A2 | Mat a ade5, his7, met10, trp1, ura3-52, cdc25-2 (from Mark Lemmon) |

| GY1217 | Mat a ura3-52, leu2-3, 112, his3Δ200, trp1 |

| GY3174 | Mat α leu2-3, 112 ura3-52, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 MSS4 (from Scott Emr) |

| GY3175 | Mat α leu2-3, 112 ura3-52, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, mss4::HIS3 MX6 carrying Ycplac111 mss4-102 LEU2 (from Scott Emr) |

| GY3176 | Mat a gic2::HIS3, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-GFP, URA3, CEN) (from Clarence Chan) |

| GY3177 | Mat a gic2::HIS3, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN) |

| GY3178 | Mat a gic2::HIS3, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN, 1134A, S135A, P137A) |

| GY3181 | Mat a gic2::HIS3, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN, K109A, K110A, K119A, K120A, K121A) |

| GY3182 | Mat a gic2::HIS3, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN, K109A, K110A, K119A, K120A, K121A, I134A, S135A, P137A) |

| GY3183 | Mat α gic1::LEU2 gic2::TRP1, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-GFP, URA3, CEN) (from Clarence Chan) |

| GY3184 | Mat α gic1::LEU2 gic2::TRP1, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN) |

| GY3185 | Mat α gic1::LEU2 gic2::TRP1, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN, I134A, S135A, P137A) |

| GY3188 | Mat α gic1::LEU2 gic2::TRP1, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN, K109A, K110A, K119A, K120A, K121A) |

| GY3189 | Mat α gic1::LEU2 gic2::TRP1, his3-Δ200 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 lys2-801, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, K109A, K110A, K119A, K120A, K121A, I134A, S135A, P137A, URA3, CEN) |

| GY3199 | Mat a bar1, ura3, trp1, leu2, his2, ade1, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN) |

| GY3204 | Mat a cdc34-3, bar1, ura3Δns, trp1-1a, leu2, 112, his2, ade1, (pRS316-ADH-Gic2-GFP, URA3, CEN) |

Microscopy—Cells were grown to early log phase (A600 = 0.6–0.8) in synthetic complete medium and fixed as described previously (12). GFP-Gic2 was scored as polarized when it appeared as a single patch in the bud of small budded cells. For actin staining, cells were stained with Alexa Fluoro 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen) after fixation and permeabilization as described previously (13).

Ras Rescue Assay—Characterization of the proteins that bind to PI(4,5)P2 at the PM by Ras-rescuing assay was performed as described previously (14). To generate Gic2N-RasQ61L(ΔF) fusion constructs, PCR fragments containing the N terminus of GIC2 were subcloned into the p3SOB-L2 vector (a gift from Dr. Lemmon). The resulting constructs were transformed into the cdc25ts mutant strain. Transformants were streaked out onto synthetic complete-leucine plates and incubated at the permissive (25 °C) or restrictive (37 °C) temperature for 3 days. RasQ61L(ΔF) fused with PLCδ-PH and Dynamin-PH, respectively, were used as positive and negative controls.

Preparation of GST-Gic2NT Protein—Escherichia coli expressing GST-tagged Gic2NT wild-type and mutant proteins were induced overnight at 18 °C, and all subsequent steps were performed at 4 °C unless otherwise stated. Bacterial pellets were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and sonicated in the presence of 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 1% Triton X-100 was added to increase solubility. The solution was centrifuged at 14,500 × g for 25 min, and the supernatant was filtered to remove insoluble material. The supernatant was then incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (prewashed with phosphate-buffered saline) for 1.5–2 h and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (all washes were done at 500 × g for 5 min). GST-Gic2NT on beads were used directly for the in vitro binding assay, while GST-Gic2NT for the large unilamellar vesicle (LUV) sedimentation assay were first eluted from the GST beads with 30 mm reduced glutathione in 150 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and dialyzed with HNa100 buffer.

In Vitro Binding of Cdc42 and Gic2NT—His6-Cdc42 was prepared using the same protocol as the preparation of GST-Gic2NT, except that the bacterial pellets were washed in extraction buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, and 300 mm NaCl), 1% Triton X-100 was not added after sonication, the protein was eluted with extraction buffer + 200 mm imidazole, and the protein was dialyzed with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, + 150 mm NaCl. GST-Gic2NT and GST-gic2NT(pb) on beads were blocked with blocking buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm DTT, and 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) for 2 h at 4 °C. His6-Cdc42 was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT to strip the nucleotides and then incubated at room temperature for 60 min in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, and 0.5 mm GTPγS. The nucleotide-loaded His6-Cdc42 was added to the blocked GST proteins and rotated at 4 °C for 2 h. Beads were washed in blocking buffer minus bovine serum albumin and resuspended in 1× SDS sample buffer. 10 μg of His6-Cdc42 and 10 μg of GST-Gic2NT protein were used for each reaction.

LUV Sedimentation Assay—LUV sedimentation assay was performed as described previously (15). LUVs with 100 nm diameter were prepared by size extrusion. Lipid components were mixed at different molar ratios, dried with nitrogen stream, and resuspended at a concentration of 2 mm in a buffer containing 12 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, and 176 mm sucrose. The mixed lipids were subjected to five cycles of freeze-thaw and 1 min of bath sonication before being passed through 100-nm filters using a mini-extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL). LUVs were dialyzed overnight in the HNa100 buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT). The percentages of phosphatidylserine (PS) and PI(4,5)P2 indicated in the text are the molar percentages of total PS and PI(4,5)P2, with the remainder being phosphatidylcholine (PC). Lipid concentrations are given as total lipid. The binding of 300 nm Gic2 to LUVs was determined by sedimentation assays conducted in 200 μl of total volume in an ultracentrifuge TLA-100 rotor (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA). The tubes were preincubated for 1 h in a 50-μm solution of PC in the HNa100 buffer to prevent nonspecific binding of Gic2 to polycarbonate centrifuge tubes. Sucrose-loaded LUVs were precipitated at 150,000 × g for 30 min at 25 °C. The supernatants and pellets were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with SYPRO red (Invitrogen) for quantification of free and bound materials with the ImageQuant software.

Subcellular Fractionation—Protocol for subcellular fractionation of yeast lysates was adapted from Goud et al. (16). Cells were grown in synthetic complete medium plus the appropriate amino acids overnight at 25 °C; at an optical density of ∼0.6 they were shifted to 37 °C for 90 min. Cells were washed in 10 mm NaN3 and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min in spheroplast wash buffer (1.4 m sorbiol, 50 mm KPi, pH 7.5, and 10 mm NaN3), supplemented with 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.15 mg/ml zymolyase 100T. The spheroplasts were resuspended in lysis buffer (0.8 m sorbitol, 10 mm triethanolamine, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.2, and a protease inhibitor mixture including AEBSF (4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride), E64, pepstatin A, and 1,10-phenanthroline), left on ice for 10 min, transferred to a Dounce homogenizer (Kontes Glass Co., Vineland, NJ), and lysed with 20 strokes from the A pestle. Cells were then spun at 500 × g for 10 min to generate the pellet (P1) and the supernatant (S1) fractions. The supernatant was then spun for 13,000 × g for 30 min to generate the P2 and S2 fractions. The protein concentration in S2 was used to normalize samples. For whole cell lysates, after spheroplast formation cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 1 mm EDTA. Cells were left on ice for 10 min and were then broken by vortex.

RESULTS

The Polybasic Region of Gic2 Binds to PI(4,5)P2 on the Plasma Membrane—The Cdc42 effector Gic2 is localized to the bud tip in budding yeast and is required for bud emergence (5, 6). The N terminus of Gic2 contains both a Cdc42-interacting CRIB domain and a polybasic region containing a number of positively charged (basic) residues (Fig. 1A). The exocyst component Sec3 is another downstream effector of Cdc42 (17). We have recently discovered that an N-terminal polybasic region adjacent to the Cdc42 binding domain of Sec3 directly interacts with PI(4,5)P2 (18). While the N terminus of Sec3 is important for its function in exocytosis, a gic2-sec3 chimera with the N terminus of Sec3 replaced by the N terminus of Gic2 behaves like the wild-type SEC3 in yeast cells. Furthermore, mutations in the polybasic region of gic2-sec3 chimera abolished its ability to replace SEC3 in yeast cells (18). These data suggested to us that the polybasic region of Gic2 might play an important role in the localization and/or function of Gic2 in cell polarity.

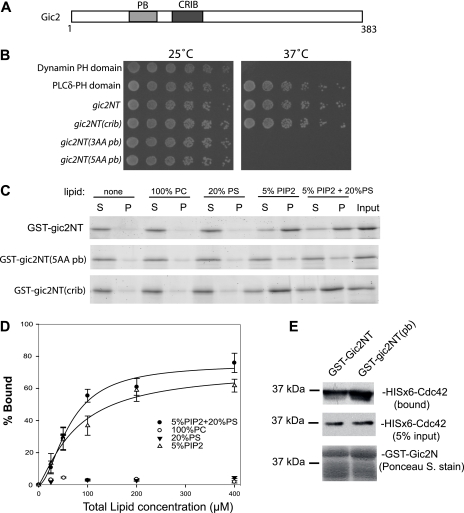

FIGURE 1.

Gic2 binds to phospholipids through its N-terminal polybasic region. A, schematic diagram of Gic2 domain structure. PB, polybasic region; CRIB, the CRIB domain that interacts with Cdc42. B, gic2NT fused to RasQ61L(ΔF) requires an intact polybasic domain for Ras rescue in cdc25 mutant cells. Wild-type (gic2NT), CRIB domain mutant (gic2NT(crib)), or polybasic region mutant harboring K119A, K120A, K121A mutations (gic2NT(3AA pb)) or K109A, K110A, K119A, K120A, K121A mutations (gic2NT(5AA pb)) were fused to RasQ61L(ΔF) and transformed into the temperature-sensitive cdc25 mutant cells. The wild-type and CRIB domain mutant of Gic2 were able to rescue the cdc25 mutant at the restrictive temperature of 37 °C. The polybasic mutants were unable to grow at 37 °C, suggesting that the negatively charged residues in the polybasic region of Gic2 are important for its association with the PM. The PH domains from phospolipase δ (PLCδ) and dynamin were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, in this assay. C, GST-gic2NT, GST-gic2NT(5AA pb), or GST-gic2NT(crib) (amino acids 1–155) were incubated with LUVs containing 100% PC, 20% PS, 5% PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate), or a combination of 5% PIP2 and 20% PS. After ultracentrifugation, proteins in supernatant (S) and pellet (P) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and visualized by SYPRO® red staining. GST-gic2NT and GST-gic2NT(crib) bound to LUVs containing 5% PIP2 and 5% PIP2 + 20% PS, whereas GST-gic2NT(pb) did not bind to any of the lipids. D, GST-gic2NT was incubated with increasing concentrations of LUVs composed of 5% PIP2, 20% PS, 100% PC, or 5% PIP2 + 20% PS for the binding reaction. The percentage of lipid-bound GST-gic2NT was plotted with the increasing liposome concentration with a single rectangular hyperbola equation (B = BmaxX/[Kd + X]) using SigmaPlot. Each point is the average of three measurements. The error bars designate the S.D. E, the gic2NT(pb) mutant remains capable of interacting with Cdc42. GST-gic2NT and GST-Gic2NT(pb) were loaded onto glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and incubated with His6-Cdc42 for 2 h. After beads were washed, sample buffer was added and samples were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel. His6 antibody was used to detect His6-Cdc42 (both bound and 5% of total His6-Cdc42), and Ponceau S staining was used to detect GST-gic2NT protein.

To determine whether Gic2 can interact with the PM, we first performed a Ras rescue assay. Like the yeast two-hybrid system for testing protein-protein interactions, the Ras rescue assay provides an efficient assay of protein-lipid interaction in yeast cells. This assay employs a yeast temperature-sensitive strain with mutations in CDC25, which encodes the guaninenucleotide exchange factor for Ras. At the restrictive temperature of 37 °C, Ras-GDP at the PM cannot be converted to Ras-GTP and cells cannot grow (14). The suspected PM binding domain is then fused to RasQ61L(ΔF), the constitutively active form of Ras lacking its farnesylation signal for PM association. If the domain can, in fact, associate with the PM, RasQ61L(ΔF) will be localized to the PM and the mutant CDC25 cells will be “rescued” at 37 °C. The Ras rescue assay has been used to identify proteins that bind to PI(4,5)P2 in the inner leaflet of the PM in yeast (14). We fused the N terminus of Gic2 (amino acids 1–155) containing both the polybasic region and the CRIB domain to RasQ61L(ΔF). If the wild-type or mutant Gic2NT can associate with the PM, the activated Ras protein RasQ61L(ΔF) can be brought to the PM, therefore bypassing the need of Cdc25 to allow cell survival at 37 °C. Beginning with the Gic2 N-terminal wild-type construct (“gic2NT”), we mutated some of the basic residues within the polybasic region: K119A, K120A, and K121A (“gic2NT(3AA pb)”), and K109A, K110A, K119A, K120A, and K121A (“gic2NT(5AA pb)”). We also mutated key residues within the CRIB domain that have been shown previously to be essential for Cdc42 binding (I134A, S135A, P137A, “gic2NT(crib)”) (19). We found that cells containing RasQ61L(ΔF) fused with wild-type gic2NT and gic2NT(crib) grew at 37 °C, but those fused with gic2NT(3AA pb) or gic2NT(5AA pb) failed to grow (Fig. 1B). The positive control, a fusion protein containing the PLCδ-PH domain, and the negative control, a fusion protein containing the dynamin-PH domain that has a weaker affinity for PI(4,5)P2 (20), worked as expected. These results suggest that the polybasic domain mediates the association of Gic2 with the PM.

Polybasic regions on a number of proteins have been found to directly interact with negatively charged phospholipids such as PI(4,5)P2 on the inner leaflet of the PM (21, 22). Therefore, we tested whether gic2NT binds directly to PI(4,5)P2 and whether the polybasic region mediates this interaction. We performed an in vitro lipid binding assay by examining the binding of recombinant GST-gic2NT to large LUVs containing various phospholipids by co-sedimentation. As shown in Fig. 1C, GST-gic2NT bound to LUVs containing 5% PI(4,5)P2, but not 20% PS or 100% PC. GST-gic2NT did not bind to PI and showed weaker binding to PI(3,5)P2 (supplemental Fig. 1). GST-gic2NT (5AA pb) was unable to bind to PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the polybasic region of Gic2 is critical for its ability to bind to PI(4,5)P2. Similar to GST-gic2NT, GST-gic2NT(crib) was still able to bind to PI(4,5)P2, indicating that the CRIB domain is not required for Gic2 to bind to PI(4,5)P2. To measure the affinity of these interactions, we examined the binding of gic2NT to LUVs with increasing lipid concentrations. The bound GST-gic2NT was quantified and plotted against the total lipid concentration with the equation: B = BmaxX/[Kd + X]. (Kd is the dissociation constant; X and B represent the concentrations of the free Gic2 and the bound Gic2, respectively, Fig. 1D). The Kd was calculated by nonlinear regression; the Kd for 5% PI(4,5)P2 alone is 56.2 μm and for a mixture of 5% PI(4,5)P2 and 20% PS is 55.4 μm. The gic2NT(pb) mutant remains capable of interacting with Cdc42 (Fig. 1E).

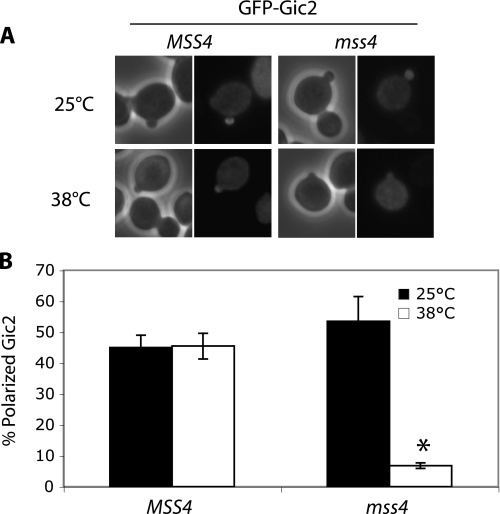

Gic2 Localization at the Bud Tip Is Disrupted in a Yeast Mutant Lacking PI(4,5)P2 at the PM—The above Ras rescue assay and in vitro binding experiments suggest that Gic2 binds to PI(4,5)P2 via its N-terminal polybasic region. To further investigate the role of PI(4,5)P2 binding in Gic2 function, we examined the localization of GFP-Gic2 in cells lacking PI(4,5)P2 at the PM. We used a temperature-sensitive mutant of MSS4, which encodes a major PI(4)P 5-kinase that catalyzes the production of PI(4,5)P2 at the PM. At the restrictive temperature of 38 °C, the level of PI(4,5)P2 in the PM is greatly reduced in the mutant cells (23, 24). We found that small budded control cells (MSS4) displayed polarized GFP-Gic2 at either 25 or 38 °C (Fig. 2). A similar percentage of the mss4 mutant cells with polarized GFP-Gic2 was observed at 25 °C, albeit the signal was not as concentrated as that in the wild-type cells, possibly as a result of a slightly reduced PI(4,5)P2 level in the mss4 mutant even at 25 °C (23, 24). However, at 38 °C, <10% of the small budded mss4 cells displayed polarized GFP-Gic2. Together, the results suggest that Gic2 polarization at the bud tip is regulated by PI(4,5)P2.

FIGURE 2.

Gic2 association with the bud tip is disrupted in the mss4 mutant. A, wild-type (MSS4) and temperature-sensitive mss4 mutants were transformed with GFP-GIC2. At 25 °C, both wild-type and mss4 mutant had polarized localization of GFP-Gic2 in the small budded cells, whereas at 38 °C only wild-type cells had polarized GFP-Gic2. B, quantification of the percentage of small budded cells that contained polarized localization of GFP-Gic2. Data are the average from two separate experiments; error bars represent S.E. (*, p <0.01).

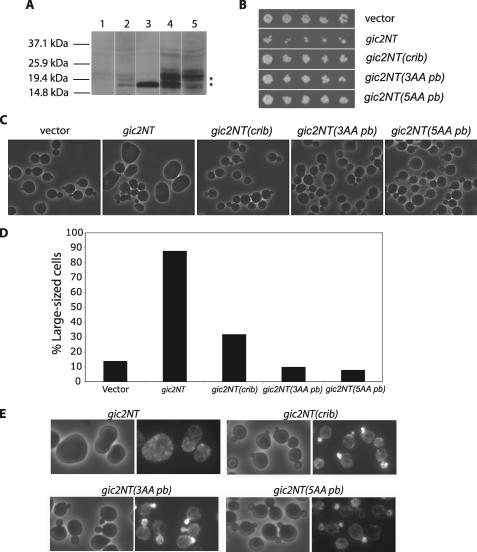

The N-terminal Polybasic Region of Gic2 Is Important for Its Function in Cell Polarity—A previous report found that overexpression of the N terminus (amino acids 1–208) of Gic2 under an inducible promoter resulted in large and round cells (9). Therefore, the N terminus of Gic2 may be dominant negative in yeast cells. To determine whether the polybasic region is important for the function of Gic2 in cell polarity, we overexpressed gic2NT (amino acids 1–155), gic2NT containing mutations in the CRIB domain (gic2NT(crib)), or gic2NT containing mutations in the polybasic region (gic2NT(3AA pb) and gic2NT(5AA pb)) in yeast cells using a centromere-based vector under the TEF promoter. As shown in Fig. 3B, expression of gic2NT resulted in slower cell growth. We also found that a higher level of expression using a 2μ vector resulted in cell inviability (not shown). Cells transformed with vector alone had no effect on growth. Overexpression of the N terminus harboring mutations in the CRIB domain or the polybasic region did not affect cell growth, even though they were expressed at even higher levels than gic2NT in yeast cells (Fig. 3A). This result suggests that the polybasic region, as well as the CRIB domain, is necessary to confer the dominant negative effect of gic2NT in the inhibition of growth.

FIGURE 3.

Overexpression of the N terminus of Gic2 (gic2NT) caused morphological and growth defects that require both an intact polybasic region and a CRIB domain. Yeast cells were transformed with CEN plasmids containing the wild-type or mutant forms of gic2NT with mutations in the CRIB domain or polybasic domain. Cells transformed with vector were used as a negative control. A, Western blot analysis of Myc-gic2NT expression levels in cells using the anti-Myc antibody. Lane 1, vector; lane 2, Myc-gic2NT; lane 3, Myc-gic2NT(crib); lane 4, Myc-gic2NT(3AA pb); lane 5, Myc-gic2NT(5AA pb). gic2NT had a lower expression level compared with the mutants. gic2NT(3AA pb) and gic2NT(5AA pb) had slower mobility on SDS-PAGE, probably due to the mutations. B, the growth of cells expressing the various mutants was tested on plates at 25 °C. Expression of the wild-type gic2NT is inhibitory to growth. However, mutations in the polybasic region or CRIB domain abolished this inhibitory effect. C, cells expressing gic2NT or gic2NT mutants were observed by microscopy at the same magnification. Note that gic2NT cells were rounder and much larger in size than vector controls or mutant cells. D, quantification of the percentage of cells whose length was at least 10% larger than the average length of vector-only cells. Cells expressing gic2NT were large in size, suggesting depolarized cell surface growth; ∼30% of the cells expressing gic2NT(crib) were also large in size, and cells expressing vector alone or gic2NT(pb) were normal in size. Graph is from a representative experiment (n = 50). E, actin in cells expressing wild-type and mutant gic2NT was stained with Alexa Fluoro 488 phalloidin. Actin is depolarized in large cells expressing gic2NT, but not in cells expressing gic2NT mutants.

We next examined the morphology of the cells expressing the above gic2NT constructs. Consistent with the previous report (9), cells expressing gic2NT were abnormal in shape and significantly larger than cells expressing vector alone (Fig. 3C), suggesting a defect in cell polarity. In contrast, cells expressing gic2NT(crib), gic2NT(3AA pb), and gic2NT(5AA pb) mutants were approximately the same size as the vector control cells (Fig. 3, C and D). We have also examined F-actin in these cells by Alexa Fluoro 488 phalloidin staining. Actin was depolarized in large cells expressing gic2NT, but not in cells expressing gic2NT mutants (Fig. 3E). Therefore, the polarity defects observed with expression of gic2NT require both the CRIB domain and the polybasic region. This dominant negative analysis suggests that the CRIB domain and the polybasic region are necessary for Gic2 function in cell polarity.

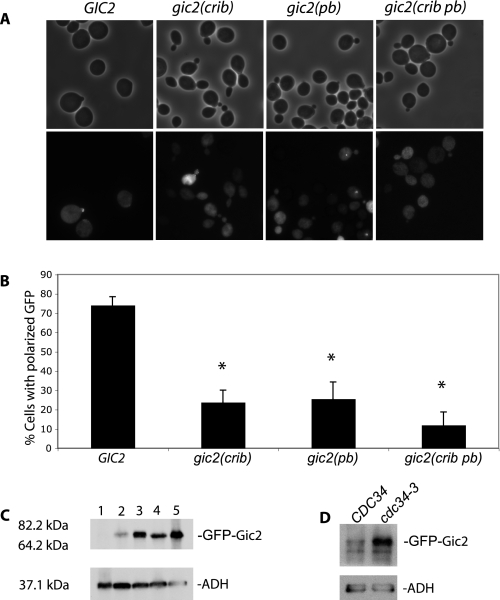

The Polybasic Region and the CRIB Domain Are Important for Gic2 Localization—Phospholipids are important regulators of intracellular functions. Our observation that Gic2 contains a polybasic region that interacts with PI(4,5)P2 brings up the possibility that the polybasic region is involved in regulating the localization of Gic2 in yeast cells. To determine whether this is the case, we expressed full-length GFP-GIC2, GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb) (5AA), or a combination of both mutations, GFP-gic2 (crib pb) in gic2Δ cells. We grew the cells at 25 °C and then shifted to 37 °C for 90 min, because it is known that Gic1 and Gic2 play an essential role in polarized growth at 37 °C (5, 6). We found that GFP-Gic2 was polarized to the bud tip in the majority of small budded cells (74%) (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, a significantly smaller percentage of small budded cells displayed polarized GFP-gic2(crib) (24%), GFP-gic2(pb) (26%), or GFP-gic2(crib pb) (12%). Therefore, the polybasic region and CRIB domain are both critical for polarization of Gic2. Because the wild-type Gic1 is present in the gic2Δ strain, these cells are normal in morphology. Thus, the observed depolarization of gic2 variants was not a result of general loss of cell polarity in the cells. Because Gic2 is specifically expressed shortly before budding and is ubiquitinated and degraded after the small budded stage (7, 9), most large budded cells do not have GFP-Gic2 signal. On the other hand, the gic2 variants were frequently found in cells at later stages of the cell cycle. Consistent with this finding, we found greater amounts of GFP-gic2 mutants as compared with wild-type GFP-Gic2 in whole cell lysates (Fig. 4C). To further verify that the level of GFP-Gic2 was controlled by ubiquitination and degradation, we expressed GFP-Gic2 in the yeast cdc34-3 mutant, which is defective in the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Cdc34 (7, 9). We found that significantly more GFP-Gic2 proteins were accumulated in cdc34-3 cells than in wild-type CDC34 cells (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

The polybasic region of Gic2 is important for the localization of Gic2 to the bud tip membrane. A and B, full-length GFP-GIC2, GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb), or GFP-gic2(crib pb) mutants were expressed in gic2Δ cells, and both phase and GFP-fluorescence images were taken. Although a majority of GFP-Gic2 was polarized to the bud tips in small budded cells, most of the mutants (GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb), GFP-gic2(crib pb)) were depolarized. Note that because Gic2 is specifically expressed shortly before budding and is ubiquitinated and degraded after the small budded stage, most large budded GFP-GIC2 cells do not have GFP-Gic2 signal. On the other hand, the gic2 mutants were frequently found in large budded cells. Data are the average from three separate experiments; error bars represent S.E. (*, p <0.01). C, protein levels of GFP-gic2 with mutations in the CRIB domain and polybasic region are higher than the wild-type GFP-GIC2. GFP-tagged wild-type and mutant Gic2 were expressed in gic2Δ cells. Lane 1, vector; lane 2, GFP-Gic2; lane 3, GFP-gic2(crib); lane 4, GFP-gic2(pb); lane 5, GFP-gic2(crib pb). Gic2 protein levels in whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot using the anti-GFP antibody. Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) was used as a control for loading. D, GFP-Gic2 was expressed in wild-type (CDC34) and cdc34-3 mutant cells defective in E2 ubiquitin conjugation. Significantly more GFP-Gic2 proteins were accumulated in cdc34-3 cells than in the wild-type cells.

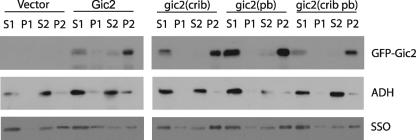

Mutations in the Polybasic Region or the CRIB Domain of Gic2 Are Not Sufficient for Disrupting Its Physical Association with the PM—Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 are distributed to the PM. We thus determined the effect of the CRIB domain and polybasic region mutations on the ability of Gic2 to associate with the PM. We separated the PM from the cytoplasm by subcellular fractionation (16) in gic2Δ cells transformed with vector, GFP-GIC2 or GFP-gic2 mutants. Interestingly, we found no clear shift from the PM fraction (P2) to the cytoplasmic fraction (S2) for any of the mutant Gic2 proteins (Fig. 5), suggesting that the mutations do not affect the association of Gic2 with the PM. This result suggests that Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2, although required for the polarization of Gic2 in small buds, may not be the only factors that physically link Gic2 to the PM. Although these results were obtained in the gic2Δ strain background, similar results were obtained when we used the gic1Δ gic2Δ strain background (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Mutations in the CRIB domain or the polybasic region do not affect the association of Gic2 with the PM. Full-length GFP-GIC2, GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb), or GFP-gic2(crib pb) mutants were expressed in gic2Δ cells. Cell lysates were prepared and centrifuged at 500 × g to remove nuclei and unbroken cells (P1), and the supernatant (S1) were further spun at 13,000 × g to generate S2 and P2. P2 contains mostly plasma membrane. Equal volumes of samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. Top row, blots were probed with an anti-GFP antibody to detect GFP-tagged Gic2. For cells transformed with vector control and GFP-GIC2 (top left), the blots were exposed longer because the expression level of GFP-Gic2 was lower than the GFP-gic2 mutants due to ubiquitin-mediated degradation, as discussed in “Results.” Note that the wild-type and mutant GFP-gic2 all show an enrichment in the P2 fractions. The middle row of blots shows the cytosolic protein ADH probed with an anti-ADH antibody; ADH was found mostly in the supernatant fraction (S2) and is a control for loading and for fractionation. The bottom row of blots show the soluble NSF attachment protein receptor (target-SNARE) Sso1, which is mainly associated with the plasma membrane but also cycles through endocytosis to internal membranes/vesicles. Sso1 was found mostly in the P2 fraction but was also found to a lesser extent in S2.

The Polybasic Region and the CRIB Domain of Gic2 Are Important for Gic2 Function during Yeast Budding—Because the polybasic region plays a role in the localization of Gic2 to the bud tip, we would expect to observe morphological defects in yeast cells that express the polybasic mutant as the sole copy of Gic protein. Because Gic1 and Gic2 are thought to have overlapping functions in polarized cell growth and are required for cell viability at 37 °C, we transformed the GFP-gic2 mutants into a gic1, gic2 double deletion strain. The cells were grown at 25 °C and then shifted to 37 °C for 90 min. The gic1Δ gic2Δ cells expressing a control vector were large and round, consistent with previous reports (5, 6). As expected, the gic1Δ gic2Δ cells were complemented by GFP-GIC2, as manifested by their normal size and shape (Fig. 6, A and B). Cells expressing GFP-gic2(crib) were larger than cells expressing wild-type GFP-GIC2, and cells expressing GFP-gic2(pb) or GFP-gic2(crib pb) were even larger than those expressing GFP-gic2(crib). We further examined actin organization in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells expressing GFP-GIC2 and GFP-gic2 variants. Actin was well polarized in cells expressing GFP-GIC2. In large sized cells expressing GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb), and GFP-gic2(crib pb), actin was depolarized (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Mutations in the polybasic region of Gic2 affect cell polarity. A and B, full-length GFP-GIC2, GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb), GFP-gic2(crib pb) mutants or vector alone were expressed in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells and shifted to 37 °C for 90 min before imaging. A portion of the GFP-gic2(crib) cells were rounder and larger (quantified by measuring the width of the cells) than GFP-GIC2 or vector; cells expressing GFP-gic2(pb) and GFP-gic2(crib pb) were even larger than the GFP-gic2(crib)-expressing cells. Graph is from a representative experiment (n = 50). C, actin in gic1Δ gic2Δ cells expressing GFP-GIC2 and GFP-gic2 mutants was stained with Alexa Fluoro 488 phalloidin. Actin was well polarized in cells expressing GFP-Gic2. In large-sized cells expressing GFP-gic2(crib), GFP-gic2(pb), and GFP-gic2(crib pb), actin was depolarized. D, gic1Δ gic2Δ cells expressing the vector control, GFP-GIC2, or GFP-gic2 mutants were serially diluted and replicated onto synthetic complete plates. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 3 days. Cells expressing either vector alone or the GFP-gic2(crib pb) mutant were clearly slow in growth, and cells expressing the GFP-gic2(pb) mutant were slightly slow in growth.

Consistent with the changes in cell morphology and actin organization described above, we found that gic1Δ gic2Δ cells expressing the GFP-gic2(pb) variant were slightly slow in growth. In addition, cells expressing either the vector alone or the GFP-gic2(crib pb) variant grew at a much slower rate than either the wild-type or the single mutants (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

The establishment of cell polarity involves dynamic interactions and distributions of proteins at specific domains of the plasma membrane and complicated signal transduction processes (25). Cdc42 regulates actin organization and polarized exocytosis, which are essential for polarized cell growth in the budding yeast (1, 2, 3, 26). The roles of Cdc42 in these processes are mediated through its downstream effectors. One of its effectors, Gic2, is expressed specifically during early bud formation and plays an important role in the establishment of cell polarity in yeast (5, 6, 9). However, it is not clear how Gic2 is localized to the bud tip and how its function in polarity is regulated. In this study, we found an N-terminal polybasic region that directly interacts with PI(4,5)P2, and we determined that this interaction is important for polarized localization of Gic2 to the bud tip. Mutations in the polybasic region may also attenuate cell cycle-dependent degradation of Gic2. We also found that the polybasic region of Gic2 is important for its function in polarized cell morphogenesis.

Using the vesicle sedimentation assay, we determined that Gic2NT and gic2NT(crib) were able to bind to PI(4,5)P2, but gic2NT(pb) was not. In addition, localization of GFP-Gic2 to the bud tip was significantly reduced in the mss4 mutant when grown at the restrictive temperature, which is deficient in the production of PI(4,5)P2 in the PM. Although we focus on Gic2 in this study, we have noticed that Gic1 also contains a cluster of basic residues at its N terminus. We speculate that a similar regulatory mechanism may apply to Gic1.

What is the functional implication of PI(4,5)P2 interaction with Gic2? Gic2 binding to PI(4,5)P2 may help to make Gic2 more accessible to its upstream activator, Cdc42, at the PM. Consistent with this possibility is that the gic2(crib pb) mutant, with mutations in both the polybasic region and the CRIB domain, was functionally more defective than the mutant harboring mutations in the CRIB domain alone. In fact, the polybasic mutant expressed in the gic1Δ gic2Δ cells displayed more severe polarity defects than the CRIB domain mutant. These results also indicate that Gic2 may function as a “coincidence detector” of both Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 signaling during yeast budding. One example involving such a “coincidence regulator” is N-WASP, which requires interaction with both PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc42 to become fully activated for subsequent Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization (27–29). Another example is the yeast protein Cla4, which interacts with both PI4P and Cdc42 and requires inputs from both signaling pathways (30). Recently, we found that PI(4,5)P2 interacts with members of the exocyst complex and is important for polarized exocytosis (13, 18, 31). In particular, we have found that the exocyst component Sec3, through its N terminus, interacts with and is synergistically regulated by Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 during polarized exocytosis (18). In fact, the N terminus of Sec3 can be replaced with the Gic2NT for normal Sec3 function (18). A recent study also revealed that a number of yeast Cdc42 downstream effectors can associate with phospholipids in the PM (32). It is possible that the integration of signals from small GTP-binding proteins and phospholipids constitutes a common regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells.

One interesting observation from our subcellular fractionation experiments is that mutations in the polybasic region or CRIB domain were not sufficient to disrupt the association of Gic2 with the PM. Although Gic2 binds to Cdc42, this interaction may be transient in nature, which is similar to the many interactions involving small GTP-binding proteins in intracellular signaling. PI(4,5)P2 binds to Gic2 in a dose-dependent and saturable manner, and the interaction seems to be sufficient to bring Gic2NT to the PM as analyzed by the Ras rescue assay. However, this may not be the only interaction that mediates the association of the endogenous Gic2 with the PM in cells. A likely explanation is that the mutant Gic2 proteins were still able to interact with other PM-associated proteins. This result suggests that Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 are signaling molecules that regulate the polarization and function of Gic2 during yeast budding.

During this study, we found that mutations in the polybasic region of Gic2 may attenuate the cell cycle-dependent degradation of Gic2 in the cell. It was previously found that Gic2 is degraded in a Cdc42-GTP-dependent manner shortly after bud emergence. Gic2 degradation at later stages of the cell cycle may provide a precise control over the signal transduction events for yeast budding (9). It is possible that PI(4,5)P2 contributes to the activation of Gic2 and that the interaction between PI(4,5)P2 and Gic2 is, like the interaction between Cdc42 and Gic2, a prerequisite for subsequent degradation after Gic2 has carried out its function.

Overall, our study revealed a role of PI(4,5)P2 in regulating Gic2 function in concert with Cdc42 during the establishment of yeast cell polarity. Future studies in the field may reveal more mechanistic details of Gic2 function in actin organization and polarized cell surface expansion, which may in turn provide more in vivo and in vitro assays for the analyses of the roles of Cdc42 and PI(4,5)P2 in the regulation of Gic2 function. We further speculate that the coordinated action of phospholipids and small GTPases may be a common theme in cellular regulations in many eukaryotic cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Matthias Peter, Clarence Chan, Mark Lemmon, and Scott Emr for yeast strains and reagents. We are also grateful to Dr. Peter Pryciak for sharing unpublished results.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM64690. This work was also supported by the Pew Scholars Program in Biomedical Sciences (to W. G.) and NIH Grant GM59216 (to E. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PM, plasma membrane; CRIB, Cdc42/Rac interactive binding; PI(4,5)P2 or PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; LUV, large unilamellar vesicles; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; DTT, dithiothreitol; PS, phosphatidylserine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PH, pleckstrin homology; E2, ubiquitin carrier protein.

References

- 1.Johnson, D. I. (1999) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63 54–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pruyne, D., Legesse-Miller, A., Gao, L., Dong, Y., and Bretscher, A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20 559–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park, H. O., and Bi, E. (2007) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71 48–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pruyne, D., and Bretscher, A. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113 571–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, J. L., Jaquenoud, M., Gulli, M. P., Chant, J., and Peter, M. (1997) Genes Dev. 11 2972–2982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, G. C., Kim, Y. J., and Chan, C. S. (1997) Genes Dev. 11 2958–2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaquenoud, M., and Peter, M. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 6244–6258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwase, M., Luo, J., Nagaraj, S., Longtine, M., Kim, H. B., Haarer, B. K., Caruso, C., Tong, Z., Pringle, J. R., and Bi, E. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 1110–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaquenoud, M., Gulli, M. P., Peter, K., and Peter, M. (1998) EMBO J. 17 5360–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman, F., in Guthrie, C., and Fink, G. R. (1991) Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 194, 3–21, Academic Press, San Diego, CA2005794 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumberg, D., Müller, R., and Funk, M. (1995) Gene 156 119–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zajac, A., Sun, X., Zhang, J., and Guo, W. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 1500–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He, B., Xi, F., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., and Guo, W. (2007) EMBO J. 26 4053–4065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isakoff, S. J., Cardozo, T., Andreev, J., Li, Z., Ferguson, K. M., Abagyan, R., Lemmon, M. A., Aronheim, A., and Skolnik, E. Y. (1998) EMBO J. 17 5374–5387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hokanson, D., and Ostap, E. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 3118–3123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goud, B., Salminen, A., Walworth, N. C., and Novick, P. J. (1988) Cell 53 753–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, X., Bi, E., Novick, P., Du, L., Kozminski, K. G., Lipschultz, J., and Guo, W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 46745–46750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang, X., Orlando, K., He, B., Xi, F., Zhang, J., Zajac, A., and Guo, W. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 180 145–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burbelo, P. D., Drechsel, D., and Hall, A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 29071–29074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein, D. E., Lee, A., Frank, D. W., Marks, M. S., and Lemmon, M. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 27725–27733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin, S., Wang, J., Gambhir, A., and Murray, D. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 31 151–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balla, A., Tuymetova, G., Tsiomenko, A., Várnai, P., and Balla, T. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 1282–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desrivières, S., Cooke, F. T., Parker, P. J., and Hall, M. N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 15787–15793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefan, C. J., Audhya, A., and Emr, S. D. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13 542–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson, W. J. (2003) Nature 422 766–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etienne-Manneville, S. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117 1291–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohatgi, R., Ho, H. Y., and Kirschner, M. W. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150 1299–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prehoda, K. E., Scott, J. A., Mullins, R. D., and Lim, W. A. (2000) Science 290 801–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papayannopoulos, V., Co, C., Prehoda, K. E., Snapper, S., Taunton, J., and Lim, W. A. (2005) Mol. Cell 17 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wild, A. C., Yu, J. W., Lemmon, M. A., and Blumer, K. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 17101–17110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, J., Zuo, X., Yue, P., and Guo, W. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 4483–4492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi, S., and Pryciak, P. M. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 4945–4956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.