Abstract

STIM1 has been recently identified as a Ca2+ sensor in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and an initiator of the store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) pathway, but the mechanism of SOCE activation remains controversial. Here we focus on the early ER-delimited steps of the SOCE pathway and demonstrate that STIM1 is critically involved in initiating of production of calcium influx factor (CIF), a diffusible messenger that can deliver the signal from the stores to plasma membrane and activate SOCE. We discovered that CIF production is tightly coupled with STIM1 expression and requires functional integrity of its intraluminal sterile α-motif (SAM) domain. We demonstrate that 1) molecular knockdown or overexpression of STIM1 results in corresponding impairment or amplification of CIF production and 2) inherent deficiency in the ER-delimited CIF production and SOCE activation in some cell types can be a result of their deficiency in STIM1 protein; expression of a wild-type STIM1 in such cells was sufficient to fully rescue their ability to produce CIF and SOCE. We found that glycosylation sites in the ER-resident SAM domain of STIM1 are essential for initiation of CIF production. We propose that after STIM1 loses Ca2+ from EF hand, its intraluminal SAM domain may change conformation, and via glycosylation sites it can interact with and activate CIF-producing machinery. Thus, CIF production appears to be one of the earliest STIM1-dependent events in the ER lumen, and impairment of this process results in impaired SOCE response.

Store-operated channels and store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE)3 are activated upon depletion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores (for a complete review see Ref. 1). STIM1 is a 77-kDa protein predominantly located in the ER membrane. It has one transmembrane domain and an EF hand motif in its N terminus that allows STIM1 to bind Ca2+ in the ER lumen and to function as a low affinity Ca2+ sensor in the stores (for the most recent review see Ref. 2). Upon Ca2+ depletion, STIM1 has been shown to lose Ca2+ from its EF hand, oligomerize, and accumulate into punctate structures in the ER membrane located in close proximity (10–25 nm) to the plasma membrane, followed by SOCE activation (3–9). Orai1 (also called CRACM1) is a plasma membrane protein that is now thought to be a major structural component of the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel (CRAC) (7, 10–13). Molecular knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai1 has been demonstrated to impair SOCE in a growing number of cell types (3, 10, 11, 14–20), whereas their combined overexpression was found to produce significant amplification of whole cell CRAC current (ICRAC). Several groups have proposed that SOCE activation may result from conformational coupling and a direct signal transduction from STIM1 to Orai1 (12, 16, 18, 21–23). However, potential involvement of intermediate steps and additional components that may be responsible for signal transduction from STIM1 in ER to Orai1 in plasma membrane has not been explored.

In this study we focused on the early events in ER that follow store depletion and precede puncta formation and examined the role of STIM1 in the SOCE pathway from the perspective of a diffusible messenger model (24). Calcium influx factor (CIF) is known to be produced in the cells upon depletion of Ca2+ stores (25–33) and/or a drop in intraluminal free Ca2+ concentration (33). Although the molecular identity of CIF is still unknown, its presence and biological activity was detected by numerous groups in a wide variety of cell types ranging from yeast to human (for review see Ref. 24). CIF is thought to be produced in ER, and its activity could be detected as early as 20–25 s after TG application.4 Very little is known about the molecular mechanism of CIF production in the stores, but the mechanism of CIF-induced activation of SOCE has been identified (32); when released from the stores, CIF was shown to trigger a plasma membrane-delimited cascade of reactions that start with CIF-induced displacement of inhibitory calmodulin from a plasma membrane variant of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2β (iPLA2β), which transduces the signal to store-operated channels leading to their opening and activation of SOCE. Following the diffusible messenger model of SOCE activation, we have now focused on the early ER-delimited steps in CIF-mediated SOCE pathway and discovered that CIF production is indeed restricted to ER, closely follows STIM1 expression, and requires molecular integrity of its sterile α-motif (SAM) domain. Our new studies provide the first evidence for a novel role for STIM1 as a molecular trigger for CIF production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells—NG108-15 neuroblastoma × glioma hybrid cells were obtained from ATCC. NG115-401L neuroblastoma × glioma hybrid cells were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures and cultured as suggested by the distributors. Primary smooth muscle cells were isolated from rabbit aorta and cultured as previously described (32).

Molecular Down-regulation of Endogenous STIM1—Primary SMC were used for studies of the role of endogenous STIM1 on SOCE (Ca2+ entry) and CIF production, showed the highest transfection rate (above 90%), and provided a well described native cell model of SOCE. SMC were transfected with either scrambled siRNA (Ambion) or siRNA against STIM1 (5′-AAGGCTCTGGATACAGTGCTC-3′) (14) using Lipofectamine Plus reagents (Invitrogen), as in our prior studies (32, 33). NG115 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen); the transfection rates were around 50%. All of the cells were used for experiments 40 ± 4 h after transfection.

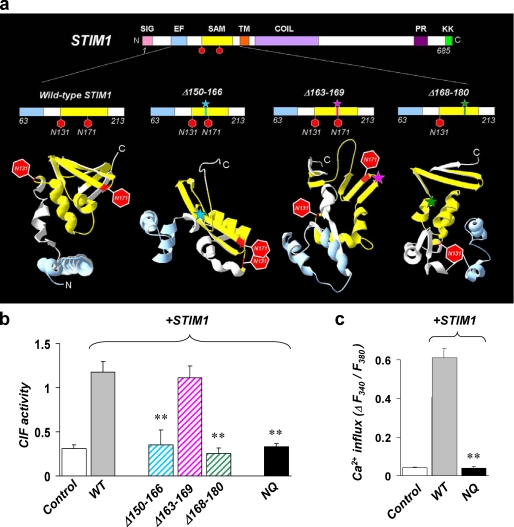

Molecular Up-regulation of STIM1—Native SMC and NG115 cells were transiently transfected with a human wild-type STIM1 construct (17) using transfection protocols described above. In a series of experiments instead of WT STIM1, NG115 cells were transfected with different mutant STIM1 constructs. Full-length STIM1 cDNA plasmid was purchased from ATCC in the pOTB7 vector. STIM1 was excised from pOTB7 vector utilizing EcoRI and Xho1 restriction sites and ligated into pcDNA3.1. Three SAM deletion mutants have been created by site-directed mutagenesis with a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit II (Stratagene) using a pCDNA3.1 vector containing STIM1. The deletions are as follows: STIM1-Δ150–166, STIM1-Δ163–169, and STIM1-Δ168–180 (see also Fig. 4a). STIM1 mutant in which the two glycosylation sites in SAM domain were mutated from asparagine to glutamine (N131Q and N171Q) (34) was a gift from Dr. Trevor Shuttleworth.

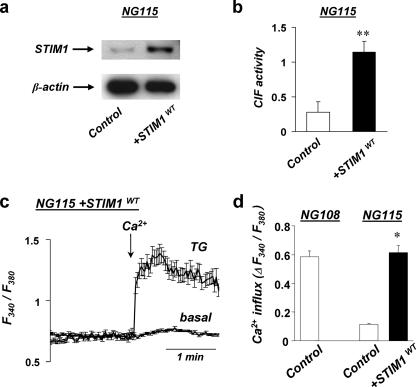

FIGURE 4.

Expression of exogenous STIM1 restores CIF production and SOCE in deficient NG115 cells. a, representative Western blot shows >10-fold increase in the amount of STIM1 protein in NG115 cells transfected with exogenous STIM1 (+STIM1WT) compared with cells transfected with empty vector (Control). b, bar graph shows the activity of CIF extracts from TG-treated NG115 cells transfected with either empty vector (Control) or with STIM1 (+STIM1WT), which were tested in experiments similar to those shown in Fig. 2. Summary from seven to nine oocyte injections of CIF extracts from three different cultures of control and +STIM1WT cells. The asterisks denote significant difference (p = 0.003). c, representative traces show the average changes (±S.E.) in intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380) recorded simultaneously in a number of individual NG115 cells in which exogenous STIM1 was expressed (+STIM1WT). The cells were pretreated with TG (TG, 1 μm, n = 38) or with 0.5% Me2SO (Basal, n = 50) for 5 min in Ca2+-free solution before 2 mm Ca2+ was added (as indicated by the arrow). d, summary data from experiments in Figs. 3(a and b) and 4c. Maximum SOCE in control NG108 cells (n = 230 from four cultures), control NG115 cells (n = 215 from four cultures), and in NG115 cells expressing exogenous STIM1 (+STIM1WT) (n = 92 from three different cultures). The asterisk denotes significant differences between control NG115 and +STIM1WT NG115 cells (p < 0.001).

Western Blots—The cells were homogenized on ice by sonication in a homogenization buffer containing 300 mm sucrose, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). The cell homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 × RPM for 10 min, and the supernatant was subjected to Western blot analysis as previously described in detail (33). To visualize STIM1 protein levels, a primary anti-STIM1 antibody (Transduction Laboratories) was used at 1:250 dilution. As a reference, β-actin was visualized with a monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam) at 1:10000 dilution.

Preparation of CIF Extracts—CIF was extracted and purified from SMC, NG108, and NG115 cells using the same protocols as we previously described for human platelets (33). Briefly, a 10-cm culture dish of control or transfected cells (36–40 h after transfection) was treated with 1 μm TG for 10 min to deplete their Ca2+ stores. Then CIF was extracted with HCl, the extract was neutralized, and vicinal phosphates were precipitated with BaCl2. The supernatant was dried (SpeedVac) and then extracted with methanol. The methanol extracts were passed through Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Waters), dried under N2 gas, and resuspended in 100 μl of 100 mm acetic acid. The reconstituted extract was clarified by centrifugal ultrafiltration through an Ultrafree-MC 30-kDa filter (Millipore). In experiments that required very significant amount of cells (such as the assessment of the time course of CIF production) Jurkat T-lymphocytes were used for CIF extraction, as previously described (29).

To ensure quantification/standardization of CIF extracts from different cell samples, the cells were counted before collection, the protein content was measured following extraction with hydrochloric acid (the first step of CIF isolation), and the volume of CIF extract was adjusted accordingly.

CIF Bioassay in Xenopus Oocytes—Purified CIF extracts were assayed for their bioactivity by injecting them into fura-2-loaded albino Xenopus laevis oocytes, as previously described in detail (33). Changes in intracellular Ca2+ were measured through a Nikon 20× Super Fluor objective (NA = 0.75), using a Nikon Eclipse TS-100 inverted microscope, a rapid excitation filter changer alternating between 340 and 380 nm (Sutter Instruments), and a CCD camera (Cooke PixelFly) and analyzed using the InCyt IM2 software (Intracellular Imaging). CIF activity was determined by the changes in intracellular Ca2+ (ΔRatio), which was calculated as the difference between the peak F340/F380 ratio (6 min after injection) and its basal level right before injection.

Preparation of ER Microsomes—ER microsomes were prepared from a large amount (eight 175-cm2 flasks/condition) of NG108 and NG115 cells similar to the experiments of Chen et al. (35). Briefly, the cells were disrupted using a Branson sonifier in a homogenization buffer containing 300 mm sucrose, 10 mm Tris, 5 mm ATP, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, pH 7.0 (Ca2+ and ATP were added to prevent premature depletion of the ER). The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and the resulting pellet was kept as control (mitochondria fraction that produced no CIF). The supernatants were taken and centrifuged two times at 100,000 × g for 60 min to yield the ER microsomes. The microsomes were resuspended in the above homogenization buffer. CIF was prepared from untreated (control) and from TG-treated (1 μm, 5 min) microsomes.

Ca2+ Influx Studies—The cells were loaded with fura-2AM, and changes in intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380) were monitored as previously described (32, 33). A dual excitation fluorescence imaging system (Intracellular Imaging) was used for studies of individual cells. The changes in intracellular Ca2+ were expressed as ΔRatio, which was calculated as the difference between the peak F340/F380 ratio after extracellular Ca2+ was added and its level right before Ca2+ addition. The data were summarized from the large number of individual cells (20–40 cells in a single run, with 3–9 identical experiments done in at least three cell preparations).

Determination of iPLA2 Activity—The activity of iPLA2 was determined using a commercial assay kit originally designed for the measurement of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity (Cayman), with modifications, as previously described in detail (32, 33). The specific activity of iPLA2 was expressed in absorbance/mg protein units.

Imaging—NG115 cells were transfected with YFP-STIM1 (Gift from Dr. Meyer) using LTX transfection reagent (Invitrogen). The cells were passed onto glass-bottomed dishes (Mat-Tek) and studied 30–36 h after transfection. The images were taken in live cells at 20 °C using a Nikon TE2000 deconvolution system with 60× oil immersion objective (N.A. = 1.4). ET Sputtered Series Mirrors were used, with excitation of 450–490 nm and emission of 500–550 nm. The planes were taken at Z intervals of 0.3 μm, and the AutoQuant Module in the NIS elements software was used to deconvolve the images. For real time recording of YFP-STIM1 fluorescence, a stack of 10 planes (with the bottom plane of the cells being in the middle) was recorded every 10 s, and the supplemental movie shows the deconvolved images of the bottom plane of the cell in real time (with 40× acceleration) during store depletion with 5 μm TG applied immediately after the first image was taken.

Structural (ab Initio) Modeling of STIM1—The structural modeling of STIM1 was performed by submitting 150-amino acid-long sequences starting from the EF-hand (amino acid 63) and containing the SAM domain (amino acids 130–200) within the human STIM1 (accession number NM_003156) and the SAM deletion STIM1 mutants for ab initio modeling to the HMMSTR/Rosetta prediction server (36). The generated models were aligned and fitted, and the reconstructed tertiary structure of STIM1 was verified using the DeepView-SwissPDB-Viewer computer program (37). We have also attempted homology modeling using the PHYRE server (UK); however, this server did not return conclusive results in case of the mutants, and thus we had to use the models created by the HMMSTR/Rosetta server. Protein structural modeling does not account for the actual N-linked oligosaccharides binding to the Asn131 and Asn171 glycosylation sites.

Statistical Analysis—Summary data are presented as the means ± S.E. Student's t test was used to determine the statistical significance of the obtained data. In case of Ca2+ imaging experiments where a large number of cells was simultaneously measured on a single coverslip, the data from all of the cells on the same coverslip were averaged and used as a single data point for the purposes of the t test. The data were considered significant at p < 0.01 (see significance levels in the individual figure legends).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In the present study, neuronal cell lines, vascular SMC, and X. laevis oocytes were used as complementary models for a wide range of experimental approaches (32, 33), which allowed us to carefully assess the initial steps in the SOCE pathway and the impact of molecular manipulation with STIM1 on CIF production and SOCE activation.

Molecular down-regulation of STIM1 (using transient cell transfection with siRNA against STIM1) resulted in significant reduction in the amount of STIM1 protein and caused inhibition of TG-induced Ca2+ influx in SMC (Figs. 1 and 2b). This result is fully consistent with reports in nonexcitable cell types (14, 16), in which the presence of STIM1 is thought to be absolutely required for its conformational coupling with and activation of plasma membrane channels. However, nothing is known about how STIM1 knockdown may affect some other processes in ER lumen that are activated upon depletion of the stores and may be involved in SOCE activation, such as CIF production.

FIGURE 1.

Down-regulation of STIM1 impairs TG-induced SOCE in smooth muscle cells. a, representative traces show the average changes in intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380) recorded simultaneously in a number of individual SMC. The cells were pretreated with TG (1 μm) for 5 min in Ca2+-free solution before 2 mm Ca2+ was added (as indicated by the arrow). TG-induced Ca2+ influx (averages ± S.E.) is shown in cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA (Control: n = 31) or siRNA against STIM1 (-STIM1, n = 33). TG-induced Ca2+ release from the stores was similar in both cell types (ΔRatio = 0.028 ± 0.004 in Control; ΔRatio = 0.032 ± 0.007 in -STIM1). b, summary data showing the maximum TG-induced Ca2+ influx in SMC in experiments described in a. Each bar summarizes results 103–215 individual cells from three to five preparations. Basal corresponds to Ca2+ entry in cells treated with 0.5% Me2SO without TG. Please notice that, in contrast with traces in a, the data here show the ΔRatio (±S.E.) values, which were calculated as the difference between the peak F340/F380 ratio after extracellular Ca2+ was added and its level right before Ca2+ addition. The asterisks denote significant differences between control and -STIM1 (p = 0.007).

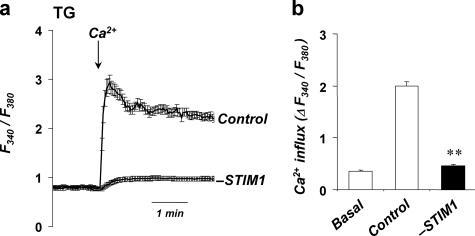

FIGURE 2.

Down-regulation of STIM1 impairs CIF production in smooth muscle cells. a, top panel shows pseudocolored ratiometric images demonstrating Ca2+ entry in a Xenopus oocyte (∼1-mm diameter) pre-loaded with fura-2 following injection of 28 nl of active CIF extract (prepared from TG-treated SMC transfected with scrambled siRNA). The asterisk in the first frame denotes the point of injection. Representative traces below show the changes in intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380) in individual oocytes following injection of CIF extracts from untreated SMC (Basal), or TG-treated SMC transfected with either scrambled siRNA (Control), siRNA against STIM1 (-STIM1), or wild-type STIM1 construct (+STIM1WT). b, representative Western blots (on the top) show that SMC transfection with STIM1 siRNA (-STIM1, left blot) resulted in about 50% (48 ± 5%) reduction in STIM1 protein expression, whereas transient overexpression of wild-type STIM1 (+STIM1WT, right blot) increased protein levels to 264 ± 34% compared with controls. The bar graphs below compare the activity of CIF extracts (maximum ΔRatio ± S.E., as measured in the assay shown in c) obtained from SMC with different levels of STIM1 expression. The left panel shows the activity of CIF extracts from untreated SMC (Basal) and TG-treated SMC transfected with either scrambled siRNA (Control) or siRNA against STIM1 (-STIM1). The right panel shows the activity of CIF from TG-treated SMC transfected with either no DNA (Control), or STIM1 construct (+STIM1WT). Each bar summarizes results from seven to seventeen oocytes injected with extracts obtained from three or four different preparations of SMC for each condition. The asterisks denote significant differences between -STIM1 and its control (p = 0.003) and between +STIMWT and its control (p < 0.001), respectively.

To test whether CIF is produced in STIM1-deficient cells, SMC were transfected with either scrambled or STIM1 siRNA. After 32–36 h they were treated with TG, and CIF was extracted from cells, purified, and then injected into X. laevis oocytes, which we routinely use as a sensitive bioassay system in CIF studies (29, 30, 33). Injection of CIF extract from control cells (transfected with scrambled siRNA) caused a strong Ca2+ influx propagating from the point of injection through the oocytes (Fig. 2a), demonstrating that upon store depletion, control SMC produce significant amounts of active CIF that can be easily detected in this bioassay. In contrast, CIF extracts from cells in which STIM1 was down-regulated did not cause any significant effect (Fig. 2), consistent with at least 10-fold reduction in the amount of CIF produced by these cells. These results demonstrated that molecular down-regulation of STIM1 dramatically impaired endogenous production of CIF, providing the first evidence for their possible connection.

To test the idea that CIF production could be controlled by STIM1, we asked what will happen when STIM1 is up-regulated. Fig. 2 demonstrates that overexpression of STIM1 in fact resulted in a dramatic increase in CIF production by the cells; extracts from STIM1 overexpressing cells (+STIM1WT) evoked about 3-fold larger responses than extracts from the control cells. Thus, expression of additional STIM1 protein was fully sufficient for significant up-scaling of CIF production, further suggesting their tight functional connection.

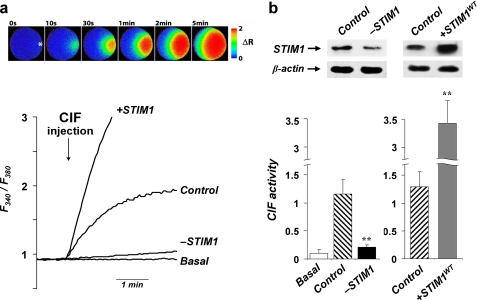

In search for additional evidence for the possibly fundamental role of STIM1 in CIF production and to gain further insights into their functional coupling, we turned to the rare neuronal cell line (NG115-401L) that features virtually no SOCE responses (27, 38). As a control, we used NG108-15 cells that are of identical origin but have fully functional SOCE machinery (39). First, we confirmed that TG-induced SOCE is normal in NG108 cells (Fig. 3a) but is impaired in NG115 cells (Figs. 3b and 4d). Because TG-induced Ca2+ release from the stores was similar in both cell types (ΔRatio = 0.078 ± 0.01 in NG108 cells, n = 25; ΔRatio = 0.074 ± 0.006 in NG115 cells, n = 34), we tested the functionality of other crucial steps in SOCE and found the following major differences. First, TG-induced depletion of the stores activated iPLA2β in NG108 cells (Fig. 3c) but failed to do so in NG115 cells (Fig. 3d). However, iPLA2β itself was present in cell homogenates and could be equally activated in both cell lines by direct displacement of inhibitory calmodulin with 10 mm EGTA (Fig. 3d). Second, contrary to normal NG108, NG115 cells produced very little CIF (27) (Fig. 3e), which can fully account for the impaired iPLA2β activation and thus the absence of SOCE following store depletion. To prove that CIF production is indeed localized to the ER, we compared CIF production in isolated ER microsomes from these two neuronal cell lines. Fig. 3f shows that active CIF extracts could be purified from depleted ER microsomes of NG108 cells that trigger normal SOCE when injected into the oocytes. Control extracts from TG-treated mitochondria and cytosol fractions of NG108 cells had no CIF activity (data not shown). In contrast to NG108, depleted ER microsomes from NG115 cells were not capable of CIF production (Fig. 3f), consistent with our results in intact cells (Fig. 3e). All of these data strongly suggested that impairment of SOCE in NG115 may be due to a significant defect in their ER resulting in their inability to translate store depletion into CIF production, resembling the results of experimental knockdown of STIM1 in SMC (Figs. 1 and 2). Indeed, Western blot analysis (Fig. 3g) revealed that the amount of endogenous STIM1 in NG115 cells was extremely low (about 10-fold lower than in NG108 cells). Supplemental Fig. S1 shows that endogenous STIM1 in NG115 cells could hardly be detected by immunostaining and showed no signs of accumulation into puncta following TG treatment of naïve cells.

FIGURE 3.

Differences in SOCE (a and b), iPLA2β activity (c and d), CIF production (e), and STIM1 expression (f) in the neuronal cell lines NG108 and NG115. a and b, representative traces show the average changes (±S.E.) in intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380) recorded simultaneously in a number of individual NG108 (a) and NG115 (b) cells. The cells were pretreated with TG (TG, 1 μm, n = 40 for NG108, n = 41 for NG115) or with 0.5% Me2SO (Basal, n = 31 for NG108, n = 37 for NG115) for 5 min in Ca2+-free solution before 2 mm Ca2+ was added (indicated by the arrows). c and d, summary data showing the activity of iPLA2 (absorbance/mg of protein) in the homogenates of NG108 (c) and NG115 (d) cells with no treatment (Basal), with TG treatment before homogenization (TG, 1 μm for 5 min), or with EGTA treatment (EGTA, 10 mm for 5 min) after homogenization (as a control for the ability of iPLA2 to get activated independently of store depletion). A summary of four to eight measurements from three different cultures of NG108 and NG115 cells is shown. e, summary bar graphs show the activity of CIF extracts from TG-treated NG108 and NG115 cells, which were tested in experiments similar to those shown in Fig. 1c. CIF was extracted from five different cultures of NG108 and seven cultures of NG115. The asterisks denote significant differences between the CIF activity of NG108 and NG115 cells (p < 0.001). f, bar graph shows the activity of CIF extracted from isolated ER vesicles from NG108 and NG115 cells. Depletion of Ca2+ from isolated ER vesicles was done by their treatment with TG, as described under “Materials and Methods.” CIF activity was tested in experiments similar to those shown in Fig. 2a. Each bar summarizes the results from four to seven oocyte injections with CIF obtained from three similar ER preparations. g, representative Western blot shows that NG115 cells contain only 11 ± 4% of STIM1 protein compared with NG108 cells.

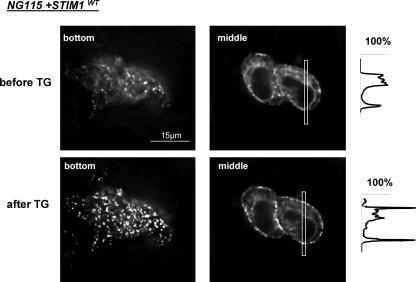

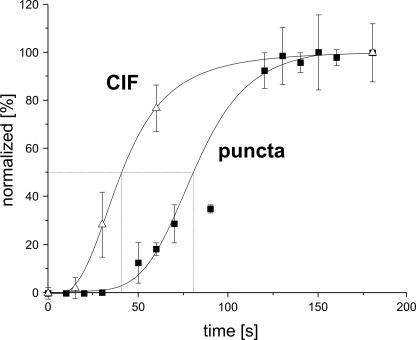

To determine whether low STIM1 expression may be the only defect in NG115 cells, we tested whether overexpression of STIM1 (with no manipulations to any other known components of the SOCE pathway) could rescue normal CIF production and SOCE in these cells. Fig. 4 shows that transient expression of exogenous human wild-type STIM1 (+STIM1WT) in NG115 cells not only caused more than 10-fold increase in STIM1 protein levels (Fig. 4a) but also rescued CIF production (Fig. 4b), which resulted in full recovery of normal TG-induced SOCE in these cells (Figs. 4, c and d). When expressed in NG115 cells, fluorescently tagged YFP-STIM1 showed the classical pattern of accumulation into punctate structures along the plasma membrane (Fig. 5 and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Analysis of the time course of puncta formation in NG115 cells (example of this process presented in supplemental Fig. S3 and the supplemental movie) showed that the first signs of puncta could be detected 40–50 s after TG application (Fig. 6), reaching a maximum at ∼130 s (with τ½ = ∼80 s). This result is in agreement with the earlier report in TG-treated Jurkat cells (5), in which the time for maximum puncta formation was found to be ∼160 s (with τ½ =∼70 s) (5). It is important to mention that the time course of puncta formation can vary depending on how fast the stores are getting depleted. For example, upon active depletion of the stores in intact cells treated with agonist (or ionomycin), puncta formation was reported to be much faster than in cells treated with TG and could peak as early as 50 s in Jurkat cells (5), and as late as 100+ s in HeLa cells (3, 8) (with τ½ ranging from 20 to 50 s). Importantly, Wu et al. (5) found that CRAC channel activation can be ∼10 s delayed and seems to follow STIM1 accumulation in puncta. In contrast to CRAC activation, we found that CIF production may significantly precede STIM1 accumulation in puncta. Fig. 6 shows that CIF production could be detected as early as 20–30 s after TG application and reached a maximum at ∼100 s (with τ½ =∼40 s), which was significantly faster than TG-induced puncta formation in NG115 cells (Fig. 6), as well as in Jurkat cells (5, 15). This is the first evidence that ER-delimited CIF production may be one of the earliest STIM1-dependent events, which preceded STIM1 accumulation in puncta and activation of ICRAC.

FIGURE 5.

Exogenously expressed YFP-STIM1 is able to form puncta in deficient NG115 cells. Live fluorescent images of representative NG115 cells expressing YFP-STIM1, before (upper panels) and after (lower panels) TG treatment (1 μm, 5 min). The images on the left show the bottom plane, and those on the right the middle plane (4.5 μm from the bottom) of the same cells. The histograms on the right show fluorescence intensities in cross-section of the cells (as indicated by the rectangles) before and after TG application. The entire deconvolved z stack is presented in supplemental Fig. S2. Translocation of YFP-STIM1 in NG115 cells in time is also shown in supplemental Fig. S3 and the supplemental movie.

FIGURE 6.

The time course of CIF production and puncta formation. The average time courses of puncta formation in NG115 cells expressing YFP-STIM1 (puncta) and CIF production (CIF) in Jurkat T-lymphocytes following application of TG. The images of NG115 cells were analyzed using ImageJ program (the particle analysis function) after the convolve filter application. The number of puncta was normalized and plotted against time. Each point shows the means ± S.E. from several experiments. The most sensitive detection of early CIF production was achieved using Jurkat cells (∼200 million cells/each time point, repeated in three different cell preparations).

Thus, we found inherent deficiency in STIM1 expression to be the only SOCE-related defect in NG115 cells that resulted in SOCE impairment. The rest of the SOCE signaling cascade in NG115 cells appeared to be totally intact, and sole expression of exogenous STIM1 was able to rescue the ability of the cells to produce CIF, to accumulate into puncta near the plasma membrane, and to initiate normal SOCE.

In search for the molecular mechanism of STIM1 involvement in CIF production, we used a combination of structural modeling and site-directed mutagenesis to find which domains of STIM1 may be crucial for this function. Because none of the known molecular domains of STIM1 could be implicated in synthetic activity, it seems highly unlikely for STIM1 to be the actual CIF synthase. However, it is reasonable to speculate that STIM1 might simply interact with and activate CIF synthase (or any part of the yet to-be-identified CIF-producing machinery). In this case, some specific domain in STIM1 should be crucial for initiation of CIF production. The SAM domain attracted our attention because it is located in ER lumen where CIF is produced. SAM is presently the least studied part of STIM1 molecule, and little is known about its role in the SOCE pathway. We created new mutants (Fig. 7a) that have small deletions in SAM domain and tested their ability to restore CIF production in NG115 cells. These deletions should not affect EF hand in the N terminus (which is essential for the ability of STIM1 to sense Ca2+) or cytosolic C terminus (which seems to be crucial for STIM1 oligomerization and accumulation into puncta). Consistent with all of these and other important functions preserved, expression of the STIM1Δ163–169 mutant was able to rescue CIF production (Fig. 7b) as well as SOCE (ΔRatio = 0.51 ± 0.01, n = 39 in NG115 transfected with STIM1Δ163–169 mutant). However, expression of another mutant, STIM1Δ168–180 (that lacks the Asn171 glycosylation site) failed to restore CIF production, suggesting that this glycosylation site may be involved in interactions with other proteins in ER and might determine the ability of STIM1 to trigger CIF production. Surprisingly, yet another mutant, STIM1Δ150–166 also failed to restore CIF production, although its glycosylation sites were not deleted. Structural (ab initio) modeling (Fig. 7a) revealed that deleting amino acids 163–169 should not have much effect on the location and accessibility of the glycosylation sites (consistent with this mutant being fully functional and able to restore CIF production). In contrast, when amino acids 150–166 were deleted, the two glycosylation sites can spatially overlap (Fig. 7a), which might result in impaired glycosylation of the mutant protein, making it functionally similar to deletion of the Asn171 glycosylation site in STIM1Δ168–180 mutant. To confirm that the structural and functional availability of the two glycosylation sites in SAM domain may be crucial for STIM1 function as a trigger for CIF production, we next tested a STIM1NQ mutant (40) in which both glycosylation sites had been mutated from asparagine to glutamine (N131Q and N171Q). Expression of STIM1NQ mutant in NG115 cells was indeed unable to restore CIF production (Fig. 7b). Consistent with the lack of CIF, expression of STIM1NQ mutant was also unable to rescue SOCE (Fig. 7c). These experiments confirmed that the presence and functional integrity of the glycosylation sites in ER-resident SAM domain of STIM1 is in fact crucial for initiation of CIF production and activation of SOCE. It is also important to mention that effects of the NQ mutant in NG115 cells (that have negligibly low amount of endogenous STIM1) appeared to be different from what was observed when the same mutant was expressed in HEK293 cells, in which endogenous STIM1 remained present (40). In HEK293 cells expression of STIM1NQ (in the presence of >30% endogenous STIM1) was sufficient to restore ICRAC. The differences in the ability of defective STIM1 mutant to restore SOCE (and/or ICRAC) depending on the presence or absence of significant amounts of endogenous STIM1 (with which it may cooperate to restore SOCE function) are not surprising and suggest that investigation of STIM1 mutants should be done preferably in cells in which endogenous STIM1 is not present.

FIGURE 7.

Molecular requirements for STIM1 function as a trigger for CIF production: the role of SAM domain and glycosylation sites. a, the location of three mutations (deletions) within SAM domain of STIM1 and their effects on the predicted tertiary structure and the orientation of the Asn131 and Asn171 glycosylation sites. Structural modeling of the intraluminal EF-hand-SAM domain part of STIM1 was performed on wild-type STIM1 and on mutant STIM1 constructs in which amino acids 150–166 (Δ150–166), 163–169 (Δ163–169), or 168–180 (Δ168–180) had been deleted by site-directed mutagenesis (see “Materials and Methods” for details). The Asn131 and Asn171 glycosylation sites are shown as red hexagons. Color-coded asterisks indicate the location of the specific deletions in the sequence and structure of the mutant SAM domains. b, bar graph shows the activity of CIF extracts from TG-treated (1 μm, 5 min) NG115 cells transfected with either empty vector (Control), wild-type STIM1 (WT), deletion mutant STIM1 constructs (Δ150–166, Δ163–169, or Δ168–180), or with a mutant STIM1 in which both glycosylation sites were mutated from asparagine to glutamine (N131Q and N171Q, shown as NQ). The bars summarize the result from four to eleven oocyte injections with CIF obtained from two or three different cultures of transfected NG115 cells. The asterisks denote significant differences between WT and Δ150–166 (p = 0.011), WT and Δ168–180 (p < 0.001), and WT and NQ (p = 0.002), respectively. c, summary data showing the maximum TG-induced Ca2+ influx in NG115 cell transfected with either no DNA (Control), with wild-type STIM1 (WT), or with the double-glycosylation mutant STIM1 (N131Q and N171Q, shown as NQ, and described in b). Each bar summarizes results from 47–142 NG115 cells from three different transfections. The asterisks denote significant differences between WT and NQ (p = 0.014).

Taken together, our data demonstrate a novel role for STIM1 as a trigger for CIF production in ER following Ca2+ depletion, which is one of the earliest STIM1-dependent events in ER that can by itself lead to SOCE activation. Indeed, when free Ca2+ concentration in the ER lumen drops and Ca2+ is lost from its EF hand, the change in STIM1 conformation may allow glycosylation sites in its SAM domain to interact with (and trigger activation of) CIF-generating machinery that STIM1 can recruit in ER. Subsequent accumulation of STIM1 (together with CIF-producing complex) into punctate structures in close proximity to the plasma membrane (3–6) may allow effective and fast delivery of CIF to its plasma membrane target, iPLA2β, which can be activated by diffusible CIF and can further transduce the signal to Orai1, leading to Ca2+ entry. Thus, STIM1-dependent activation of CIF production may go hand in hand with the ability of STIM1 to sense intraluminal Ca2+ and to accumulate in the vicinity of plasma membrane, providing important molecular, functional, and structural prerequisites for SOCE activation.

Discovery of the new role of STIM1 in CIF production, coupled with some recent evidence for additional unidentified protein required for STIM1-Orai1 interaction within ER-PM gap junctions (41) and growing evidence for iPLA2β to be an equally important component for SOCE in a variety of cell types (11, 32, 33, 42–49), strongly suggests that additional molecules, functional steps, and signaling events (in ER, at PM, and in between) may be involved in the SOCE pathway. Although direct coupling of ER-resident STIM1 to PM-resident Orai1 may be rightfully

considered as the easiest possible way of signal transduction, the functional unit of SOCE is certainly a more complex phenomenon, which is far from being understood. Molecular identity of CIF and its synthase in ER, additional scaffolding proteins in ER-PM junction, molecular architecture and mechanism of Orai1 channel activation, and a new comprehensive model of the SOCE mechanism (that may account for a majority of findings and observations that are presently used to support mutually exclusive models) are still waiting for their discovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Kirber for valuable help with imaging experiments and Dr. Trevor Shuttleworth and Dr. Tobias Meyer for kind gifts of the STIM1NQ mutant and YFP-STIM1 constructs, respectively.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1HL54150 and RO1HL71793 (to V. M. B.). This work was also supported by Training Grants HL007969 (to K. P.) and HL007224 (to V. Z.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and a supplemental movie.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: SOCE, store-operated Ca2+ entry; iPLA2, calcium-independent phospholipase A2; CIF, Ca2+ influx factor; STIM1, stromal interacting molecule 1; CRAC, Ca2+-release-activated Ca2+-conducting channel; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TG, thapsigargin; SAM, sterile α-motif; SMC, smooth muscle cell(s); siRNA, small interfering RNA; PM, plasma membrane.

P. Csutora and R. B. Marchase, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Parekh, A. B., and Putney, J. W., Jr. (2005) Physiol. Rev. 85 757-810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis, R. S. (2007) Nature 446 284-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liou, J., Kim, M. L., Heo, W. D., Jones, J. T., Myers, J. W., Ferrell, J. E., Jr., and Meyer, T. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15 1235-1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercer, J. C., Dehaven, W. I., Smyth, J. T., Wedel, B., Boyles, R. R., Bird, G. S., and Putney, J. W., Jr. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 24979-24990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu, M. M., Buchanan, J., Luik, R. M., and Lewis, R. S. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174 803-813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba, Y., Hayashi, K., Fujii, Y., Mizushima, A., Watarai, H., Wakamori, M., Numaga, T., Mori, Y., Iino, M., Hikida, M., and Kurosaki, T. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 16704-16709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luik, R. M., Wu, M. M., Buchanan, J., and Lewis, R. S. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174 815-825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liou, J., Fivaz, M., Inoue, T., and Meyer, T. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 9301-9306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, Z., Lu, J., Xu, P., Xie, X., Chen, L., and Xu, T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 29448-29456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feske, S., Gwack, Y., Prakriya, M., Srikanth, S., Puppel, S. H., Tanasa, B., Hogan, P. G., Lewis, R. S., Daly, M., and Rao, A. (2006) Nature 441 179-185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vig, M., Peinelt, C., Beck, A., Koomoa, D. L., Rabah, D., Koblan-Huberson, M., Kraft, S., Turner, H., Fleig, A., Penner, R., and Kinet, J. P. (2006) Science 312 1220-1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeromin, A. V., Zhang, S. L., Jiang, W., Yu, Y., Safrina, O., and Cahalan, M. D. (2006) Nature 443 226-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita, M., Navarro-Borelly, L., McNally, B. A., and Prakriya, M. (2007) J. Gen. Physiol. 130 525-540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos, J., DiGregorio, P. J., Yeromin, A. V., Ohlsen, K., Lioudyno, M., Zhang, S., Safrina, O., Kozak, J. A., Wagner, S. L., Cahalan, M. D., Velicelebi, G., and Stauderman, K. A. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 169 435-445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, S. L., Yu, Y., Roos, J., Kozak, J. A., Deerinck, T. J., Ellisman, M. H., Stauderman, K. A., and Cahalan, M. D. (2005) Nature 437 902-905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spassova, M. A., Soboloff, J., He, L. P., Xu, W., Dziadek, M. A., and Gill, D. L. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 4040-4045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peinelt, C., Vig, M., Koomoa, D. L., Beck, A., Nadler, M. J., Koblan-Huberson, M., Lis, A., Fleig, A., Penner, R., and Kinet, J. P. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 771-773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soboloff, J., Spassova, M. A., Tang, X. D., Hewavitharana, T., Xu, W., and Gill, D. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 20661-20665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soboloff, J., Spassova, M. A., Hewavitharana, T., He, L. P., Xu, W., Johnstone, L. S., Dziadek, M. A., and Gill, D. L. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16 1465-1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peel, S. E., Liu, B., and Hall, I. P. (2006) Respir. Res. 7 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hisatsune, C., and Mikoshiba, K. (2005) Sci. STKE 2005 e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, G. N., Zeng, W., Kim, J. Y., Yuan, J. P., Han, L., Muallem, S., and Worley, P. F. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 1003-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez, J. J., Salido, G. M., Pariente, J. A., and Rosado, J. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 28254-28264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolotina, V. M., and Csutora, P. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30 378-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randriamampita, C., and Tsien, R. Y. (1993) Nature 364 809-814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, H. Y., Thomas, D., and Hanley, M. R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 9706-9708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas, D., and Hanley, M. R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 6429-6432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas, D., Kim, H. Y., and Hanley, M. R. (1996) Biochem. J. 318 649-656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csutora, P., Su, Z., Kim, H. Y., Bugrim, A., Cunningham, K. W., Nuccitelli, R., Keizer, J. E., Hanley, M. R., Blalock, J. E., and Marchase, R. B. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 121-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trepakova, E. S., Csutora, P., Marchase, R. B., Cohen, R. A., and Bolotina, V. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 26158-26163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trepakova, E. S., and Bolotina, V. M. (2002) Membr. Cell Biol. 19 49-56 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smani, T., Zakharov, S., Csutora, P., Leno, E., Trepakova, E. S., and Bolotina, V. M. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6 113-120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csutora, P., Zarayskiy, V., Peter, K., Monje, F., Smani, T., Zakharov, S., Litvinov, D., and Bolotina, V. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 34926-34935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mignen, O., Thompson, J. L., and Shuttleworth, T. J. (2007) J. Physiol. 579 703-715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, P. Y., Csutora, P., Veyna-Burke, N. A., and Marchase, R. B. (1998) Diabetes 47 874-881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bystroff, C., and Shao, Y. (2002) Bioinformatics. 18 (Suppl. 1) S54-S61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. C. (1997) Electrophoresis 18 2714-2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bose, D. D., Rahimian, R., and Thomas, D. W. (2005) Biochem. J. 386 291-296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo, T. M., and Thayer, S. A. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 264 C641-C653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuttleworth, T. J., Thompson, J. L., and Mignen, O. (2007) Cell Calcium 42 183-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varnai, P., Toth, B., Toth, D. J., Hunyady, L., and Balla, T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 29678-29690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zablocki, K., Wasniewska, M., and Duszynski, J. (2000) Acta. Biochim. Pol. 47 591-599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shin, K. J., Chung, C., Hwang, Y. A., Kim, S. H., Han, M. S., Ryu, S. H., and Suh, P. G. (2002) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 178 37-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smani, T., Zakharov, S., Leno, E., Csutora, P., Trepakova, E. S., and Bolotina, V. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 11909-11915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanden Abeele, F., Lemonnier, L., Thebault, S., Lepage, G., Parys, J., Shuba, Y., Skryma, R., and Prevarskaya, N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 30326-30337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez, J., and Moreno, J. J. (2005) Biochem. Pharmacol. 70 733-739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singaravelu, K., Lohr, C., and Deitmer, J. W. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 9579-9592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boittin, F. X., Petermann, O., Hirn, C., Mittaud, P., Dorchies, O. M., Roulet, E., and Ruegg, U. T. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 3733-3742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross, K., Whitaker, M., and Reynolds, N. J. (2007) J. Cell. Physiol. 211 569-576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.