Abstract

This qualitative study delineates motives for residential mobility, describes dynamics between the elder and family members during the move decision process, and locates the move decision within ecological layers of the aging context. Interviews were conducted with 30 individuals and couples (ages 60-87) who experienced a community-based move within the past year, and with 14 extended family members. Reasons for moving (from perspectives of both elders who moved and their family members) were grouped into four themes and eleven issues that influenced the move decision. These themes parallel the ecological context of individual health and functioning, beliefs and attitudes, physical environment, and social pressures. Late-life mobility is a significant life transition that is the outcome of an ongoing appraisal and reappraisal of housing fit with individual functioning, needs, and aspirations. Family members are an integral part of these decision and residential mobility processes.

Well, she moved because my sister and I decided she was going to move. But she wanted to move. It wouldn’t have happened if we hadn’t decided that she was gonna move. It was a little complicated . . . - Linda Brierton’s daughter, Karen

Late life residential mobility is a significant life course event that differs from moves at other life stages in three ways:

reason for moving (Litwak & Longino, 1987; Meyer & Speare, 1985; Wiseman & Roseman, 1979),

relocation typically to a smaller home (National Association of Home Builders, 2001), and

household disbandment of a lifetime accumulation of possessions (Ekerdt, Sergeant, Dingel, & Brown, 2004; Marcoux, 2001).

Whereas the majority of elders age in place, over a 10-year period residential mobility rates for people over age 55 may be as high as 39% (Burkhauser, Butrica, & Wasylenko, 1995). By another method, five year mobility rates for those age 75+ were estimated to be 12% (Bayer & Harper, 2000).

Extended family members and other helpers influence or actively participate in decisions to relocate or to stay in place, yet their active role in this process has received little attention (Silverstein & Angelelli, 1998; Silverstone & Horowitz, 1992). Motives behind a late-life residential move are often studied as discrete categories, yet motivation theory stresses interactions across multiple components within contexts that culminate in self-regulation of behavior (e.g., Little, Hawley, Henrich, & Marsland, 2002; Ryan, 1995). This qualitative study is based on interviews with elders who completed a community-based move and their family members who helped with the process. The purpose of this study is to:

describe themes related to motives for residential mobility,

establish family members as an integral part of the residential move decision process, and

locate move motives and familial interactions within ecological layers of the aging context.

MODEL FOR THE AGING CONTEXT OF RESIDENTIAL DECISION-MAKING

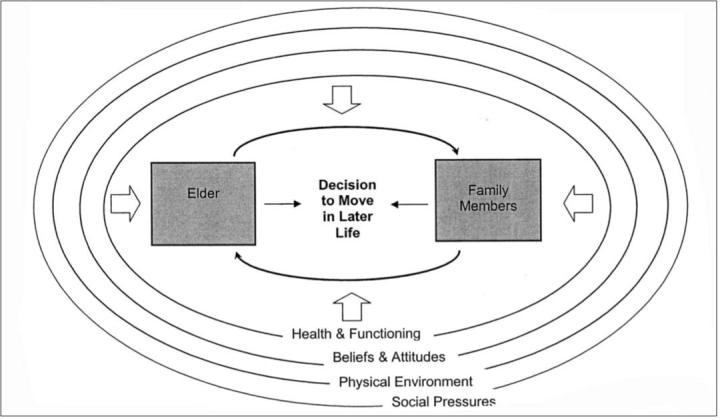

This study presents post-move perspectives on the residential decision to move, with particular emphasis on roles and interactions of the elder(s) who moved and a family member who assisted with the move. Decision-making theory has long recognized the interaction between individual level factors and social pressures and their effect on intentions and behavioral outcomes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Ecological models have been linked to decision-making processes, in part as a means to understand the roles of heuristics and communication across environments (Kirlik & Strauss, 2002). Figure 1 illustrates how both the elders and family members influence the move decision, and how each are influenced by ecological layers that comprise the context in which the person who moved is experiencing the aging process. These layers include individual health and functioning, individual beliefs and attitudes, the physical home environment, family influences, and social pressures.

Figure 1.

Model for residential decision-making in later life.

It is the authors’ premise that the residential decision process is a recurrent one. Older adults persistently experience pressures from the ecological layers of the aging context, even after a residential move has taken place. This spurs a continuous evaluation and re-evaluation of the capability of their home environment to support independence. Self-determination theory presents interactions between an individual’s innate psychological needs (i.e., competence, autonomy, relatedness) and social context as an on-going integrative process that facilitates or inhibits well-being and self-regulation of behavior (Ryan, 1995). At the level of the physical environment, Lawton’s (1982) theory of environmental fit suggests that lack of “fit” between individual competence and environmental demands may prompt a move decision. Threats to well-being spur action; this lends credence to the nature of on-going pressures from the social and environmental context (ecological influences) in the residential decision-making model.

Functional Limitations and Health

Individual health and functional limitations may challenge older adults’ ability to remain living in their current home via changes in competence, loss of independence, and need for informal support (Longino, Jackson, Zimmerman, & Bradsher, 1991; Silverstein & Zablotsky, 1996; Speare, Avery, & Lawton, 1991; Worobey & Angel, 1990). However, it appears that perceptions of one’s health are not as strong a relocation predictor as are functional limitations, at least over the short-term (Chen & Wilmoth, 2004; Colsher & Wallace, 1990). Concern over safety issues may prompt members of an elder’s social network to support or even suggest a move, particularly when they perceive the move would strengthen social interactions and assure the safety of the elder (Kennedy, Sylvia, Bani-Issa, Khater, & Forbes, 2005; Silverstone & Horowitz, 1992; Smider, Essex, & Ryff, 1996).

Individual Beliefs and Attitudes

Also at the individual level, older adults’ beliefs and attitudes may pressure toward a residential move. Beliefs and attitudes may be influenced by the personal experience of age-related changes; familial and societal expectations about “being old”; images from the media that market housing (Faircloth, 2003); and governmental policy that encourages forms of retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and other housing (Tulle & Mooney, 2002). These external messages may create an internal belief system that prompts relocation to housing that is deemed more appropriate for physical and psychological needs.

Some of these internal beliefs that might influence a decision to move have been documented in the literature. Focus groups of people ages 65 and over living in the community cited numerous factors that they believed would jeopardize their current living arrangements (Mack, Salmoni, Viverais-Dressler, Porter, & Garg, 1997). These included health of the individual or the spouse, financial problems, neighborhood changes, and loss of informal support systems. Other researchers have documented stigma against retirement facilities as including expectations of dependence, admission of incompetence, and anticipated social isolation; these may negatively influence move expectations and decisions (Fisher, 1990; Netting & Wilson, 1991). These personal attitudes and beliefs will be factors in the ongoing appraisal and reappraisal of ability to remain living at home.

Physical Environment

Lawton’s (1982) theory of environmental fit, which focuses on the congruence between individual competence and environmental demands, connects the ecological layer of the physical housing environment with the move decision process. Two aspects of the physical environment are noteworthy:

physical condition and structure of the home, and

security.

A house that is too large, needs repairs, requires high maintenance, or is in a deteriorating neighborhood may prompt a need for a change (Chevan, 1995; Maddox, 2001; Smider et al., 1996; Ward-Griffin et al., 2004). Neighborhood issues relating to neighbors, crime rates, and traffic have been cited by elders as potential security barriers to remaining in the community (Mack et al., 1997).

Family

Connections between family structure and residential mobility are well documented. Kinship structures underlie life course typologies of moves, with ability to communicate with adult children via modern technologies facilitating an early retirement move toward amenities, a second move closer towards family caregivers, and a third move toward institutionalization occurring when family caregivers are no longer able to meet elder needs on their own (Litwak & Longino, 1987). Extended family members may be drawn into the residential mobility process through the decision to move, choice of new residence, the household disbandment that accompanies a move, and the actual move itself (Dorfman, 2002; Ekerdt & Sergeant, 2006; Kennedy, Sylvia, Bani-Issa, Khater, & Forbes, 2005; Silverstein & Angelelli, 1998; Silverstone & Horowitz, 1992).

Residential mobility often involves role changes that inherently include a power shift within family structures, with the very nature of family caregiving altering the family’s natural patterns of interaction (e.g., increased number of visits); this may result in patterns of dependency that the caregiving was designed to prevent (Hummert & Morgan, 2001). Alternatively, there are aspects of residential mobility that may strengthen family interactions and individual needs for autonomy. Reciprocity and interdependence between informal caregivers and elders focus on the give and take between the elder and others within and outside the family circle, with exchanges that are free from obligation (Arber & Evandrou, 1993). Silverstone and Horowitz (1992) connect extended family to housing arrangements through autonomy negotiations within the family context, family influence on mobility patterns, and family caregiving. The sample of elders from the current study sometimes reported that participation in the move and household disbandment increased family cohesiveness (Ekerdt & Sergeant, 2006).

In the current study, the aging context is comprised of ecological layers: individual health and functional limitations, individual beliefs and attitudes, the physical environment of the home, and social pressures. Use of qualitative methodology not only identifies themes related to residential mobility motives that fall into these categories, but also highlights the additive nature of these motives, the instrumental role of extended family members, and the recurrent nature of this decision process.

METHODS

Data for this analysis were taken from 30 open-ended interviews conducted in 2002 and 2003 with men, women, and couples who moved to a smaller residence within the past year (excluding moves to nursing homes). These interviews were originally conducted to understand household disbandment (i.e., downsizing the amount of one’s household possessions) within the context of a late-life move to a smaller residence (Ekerdt et al., 2004). Also interviewed were 14 extended family members who helped with the move, most often the daughter of the person who moved.

The convenience sample was recruited in the vicinity of a mid-sized city in a Midwest state through notices in senior apartment buildings, retirement communities, a community newspaper, and by word-of-mouth referrals. The sample of elders was primarily Caucasian spanning ages 60 to 87 years (see Table 1). They had moved from 23 single-family homes as well as mobile homes, duplexes, and retirement communities. They moved into apartments (some in congregate senior housing, assisted living, or within a child’s house), and some to smaller houses. Length of time in the former home ranged from two to 33 years (mean = 14.4 years). The movers held a range of white- and blue-collar jobs prior to retirement or semi-retirement, with the majority of the sample living a middle-class lifestyle. Reported health problems ranged up to five per household, with five households specifically reporting no health problems or “good” health. The health events cited most often included heart problems, high blood pressure, and back problems. Fourteen study participants were widowed; 50% of these within the past two years. The family members interviewed included nine females and five males. These were primarily daughters and sons of the person(s) moving, although other family members (i.e., a brother, a granddaughter) were also interviewed (Ekerdt & Sergeant, 2006).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Households, Movers, and Family Members

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| By Household (n = 30) | Movers (n = 38) | ||

| Composition | Sex | ||

| Single female | 17 (57%) | Male | 13 (34%) |

| Single male | 5 (16%) | Female | 25 (66%) |

| Couple | 8 (27%) | ||

| Age | |||

| Previous housing | 60-69 years | 4 (11%) | |

| House | 23 (77%) | 70-79 years | 15 (39%) |

| Mobile home | 4 (13%) | 80-87 years | 19 (50%) |

| Duplex | 2 (7%) | ||

| CCRC | 1 (3%) | Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 36 (95%) | ||

| New housinga | Native American | 2 (5%) | |

| House | 4 (13%) | ||

| Apartment | 19 (64%) | Marital status | |

| Duplex in a CCRC | 4 (13%) | Married | 16 (42%) |

| Condo/townhouse | 3 (10%) | Single | 22 (58%) |

| Previous tenure | Years widowed (n = 14) | ||

| 1-5 years | 6 (20%) | 0-2 years | 7 (50%) |

| 6-15 years | 8 (27%) | 3-9 years | 2 (14%) |

| 16+ years | 14 (47%) | 10+ years | 5 (36%) |

| Not known | 2 (6%) | ||

| Family Members (n = 14) | |||

| Health problems | |||

| None, “good health” | 5 (17%) | Sex | |

| Heart problem | 4 (13%) | Male | 5 (36%) |

| High blood pressure | 4 (13%) | Female | 9 (64%) |

| Back problems | 4 (13%) | ||

| Hearing loss | 3 (10%) | Relationship to Mover(s) | |

| Cancer | 3 (10%) | Daughter | 8 (57%) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 2 (7%) | Son | 4 (29%) |

| Fall | 2 (7%) | Granddaughter | 1 (7%) |

| Other (1 each) | 12 (40%) | Brother | 1 (7%) |

Apartment count includes 10 moves to assisted living or congregate senior housing and one move into an apartment within a child’s home; CCRC = continuing care retirement community.

Open-ended interviews with elders were tape-recorded and transcribed; interviewers kept field notes which served as the first level of analysis. Five of the 14 interviews with helpers were conducted by phone. Early on in the course of each interview the researchers asked, “What kind of place did [you/elder] move from,” “When did [you/elder] first start thinking about moving,” “Why did [you/elder] move,” and “How was the decision made?” Additional questions provided perspective on who was in charge and emotions during the process. These questions led to the majority of the content related to move motives, with additional content suffused throughout the interviews. For the original study on household disbandment, the responses to these questions were not a primary focus, but necessary to set the context for a specific focus on disbandment, yet they provided significant narrative detail about residential mobility motives. While the use of post-move interviews provides a retroactive account of move motives, this perspective reflects the reality that has been constructed by the movers, and provides insight into the frame of mind of those who have undergone this transition.

With the assistance of NVivo software (QSR International, 2002), researchers used an interactive model of inductive and deductive reasoning to conduct qualitative analysis of the transcripts and interviewer notes (Maxwell, 1998). During the original analysis, themes related to the family context and move decision began to emerge. A literature review led to a framework for structuring this analysis around health and functioning, beliefs and attitudes, physical environment, and social pressures. To ensure reliability and reduce researcher bias, the two coders began the analysis with the same interview, compared results, and made coding adjustments based on the comparisons. The coders proceeded to analyze separate transcripts, communicating daily via personal contact, e-mail, and NVivo memos to maintain consistency. Additional coding involved searching for and finding exceptions to existing themes and identifying new themes as they evolved during the coding process, which continued until saturation was reached. Quality was further ensured by constant comparison and searches for negative cases. A previous publication described data collection, analysis, and reliability checks in greater detail (Ekerdt et al., 2004).

RESULTS

Decision-making roles, relocation motives, and evaluation of the move are described below and exemplified with quotes from a range of interviews. Names and minor details were changed in the quotes to ensure confidentiality. These examples treat individual issues in isolation, yet it is also important to understand the intricacies of the move decision process as experienced by families. To better understand the interactions between the elder who moved and family members, the experiences of five families are featured and identified by the names below. The vignette format helps illustrate interactions across ecological layers of the aging context: individual health and functional limitations, individual beliefs and attitudes, the physical environment of the home, and social pressures. Anonymous quotes in the narrative come from interviews with persons other than those in the featured five families.

Leota Jackson, age 80, moved from a mobile home to an assisted living apartment in low-income housing. She was proactive and practical in her approach to the move as a means to maintain her independence.

Mabel Connor, age 82, and her husband started planning her move when he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of lung cancer; this move paralleled her transition into widowhood. Her son, Paul, and her neighbors helped with the move.

Linda Brierton, age 84, moved after heavy persuasion by her daughters, Karen and Teresa. Linda had moved several times in the past, but this time Karen did most of the work. Linda said the move “seemed under control,” but her daughter, Karen, felt it was overwhelming as she took on an increasing caregiver role.

Genevieve Stadel, age 82, moved from a rural area to town. Her son, Will, understood how difficult the move was for his mother, yet neither had the time to take over the care of the additional house maintenance and yard work after his father died.

Steve and Susan Landers, both age 73, had experienced caregiving for other family members and were determined to avoid doing this to their children. Their move to a smaller house pulled the family together in a joint project described as a “happy time.”

The Decision-Maker

In this study, the residential mobility decision was made by the householders, but more often than not, within an extended family context. As the Brierton quote introducing this article illustrates, the interface could get complicated. By far, both elders and family members referred to the decision as belonging to the person who moved. Some who moved simply informed family members of their decision and completed the entire process themselves. One son told us, “All of a sudden, one Friday night they told me they had put the house up for sale. We were not unhappy with their decision by any means, but it was their decision.”

Degree of family involvement in the residential mobility decision was not related to age in this sample, and for some families this type of decision-making involvement was new; for other families the children had been functioning as caregivers for some time. Both elders and their family members referred to “pressure” and “support” from children in regards to the move decision. Yet in those situations where the son or daughter encouraged the parent to move, the decision was couched as belonging to the parent. Some children left the decision to their parents, but monitored the situation, ready to take action if needed. Will Stadel described how he and his sister wanted to let their recently widowed mother, Genevieve, make her own decision, yet they had a contingency plan:

We just let her know that we would support her in whatever decision she made. As long as she wanted to stay in the house we were okay with that as long as she could take care of things. If it got to the point that she couldn’t take care of things or herself, then we needed to plan for the move.

Genevieve was aware of her children’s position, and also felt pressure from previous plans made with her now deceased husband, “My husband and I had talked about it a little. . . . My son really wanted me to move. He knew it was really too much for me.”

When couples moved, they usually made the decision together. In a few cases, one spouse needed to convince the other to make the move, often with assistance from children. Paul, Mabel Connor’s son, described how difficult the situation was after his father was diagnosed with cancer, “I think the hardest part of the whole move was getting my dad moved. He was the diehard, convincing him it’s time to move on. That was hard on my mom.” Sometimes, facility tours or friends who had already moved were enlisted to help convince an elder to move.

Elders and their family members were generally in agreement as to whether the decision was made by solely the elder or with pressure from children. When family members talked about pressuring their parent to move, they also expressed feelings of remorse. This seems to be internally derived, as the elder did not see it in the same light. This was the case with one daughter, who was extremely concerned about her father’s competence within his living situation. She said, “It was more me. . . . I pushed for at least a year and by last summer it was getting ugly. I don’t know how he perceived it but in my view it was ugly, frustrating.” Her father knew his daughter was worried, but he still saw the decision as his. “My daughter was concerned. . . . We just talked about and made it happen. I just decided to do it.” Linda Brierton’s daughters Karen and Teresa were also concerned about their mother’s living situation. During the interview, Karen acknowledged the social pressure from herself and her sister, and cited several justifications over and over throughout the interview. But their mother, Linda, indicated that she did not remember any disagreements. Overall, the interviews support consideration of extended family members as an integral part of the late-life residential mobility process.

Reasons to Move

Four themes that parallel the ecological layers of the aging context emerged from elders’ and family members’ accounts as reasons to move:

individual health and functioning,

beliefs and attitudes,

physical environment of the home, and

social pressures.

The themes are further described by eleven issues as follows: individual health and functioning (health events, functional limitations, safety), individual beliefs and attitudes (new beginnings, inevitable move), physical environment (house and yard, proximity), and social pressures (social roles, friends, finances, and housing options). It is important to understand that these motives are not isolated from each other; rather it was the cumulative effect and interactions across these issues that resulted in a move decision. Some of the move reasons were characterized as reactive, as to a health event, and others as proactive, as to avoid placing children in a potential caregiving role. The majority of themes and issues were not related to the elder’s ages, with a few exceptions. The 80-87 year olds who moved and their family members were more likely than the younger age groups to cite physical body issues such as safety or “if I went down” as residential mobility motives. This older age group was also more likely than younger age groups to hold beliefs and attitudes such as the move was inevitable or “it was time” for the move.

Health Events

In the interviews, health and functioning tended to be described as distinct constructs that were described as having an impact on the decision to move regardless of income level. Health issues were directly related to a diagnosis and need for professional care, with a focus on the physical body, while functional limitations were more likely to be described in the context of inevitable aging processes and their relationship to the home environment.

Both the movers and their family members listed a wide variety of health events that contributed to the move decision. The most frequently cited health events are listed in Table 1. Leota Jackson talked about planning her move for two years, but did not actually put her name on a waiting list until she had problems with a slipped disc. Mabel Connor explained, “My husband was diagnosed with lung cancer last May and we thought we better get to town.” Her son, Paul, mirrored this reasoning in his interview, “ . . . knowing they were going to radiation therapy and everything, it would be so much easier for them to be in town.” Others mentioned mini-strokes, cognitive decline, diabetes, and a more general, “I wasn’t feeling well.” These health conditions and events would persist into the new home environment, and one perceived role for the new home was to facilitate management of the health condition.

Functional Limitations

The focus of functional limitations was on needed changes in the home environment. Both elders and family members commented on activities that the elder could no longer do: activities of daily living (e.g., heavy lifting, walking up stairs) and instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., housework, cooking). In these cases, the move was described as a reactive strategy to compensate for a functional limitation. One daughter explained how the stairs in her dad’s home made shopping difficult, “He had a bi-level and you either go up or down. And I know those stairs were bothering him for being able to carry groceries.” A son described how his mother’s new home in an assisted living apartment compensated for her declining cooking skills: “. . . she likes having meals prepared for her. As she has gotten older has lost the ability to cook, and she was eating a lot of food that wasn’t well prepared.” These quotes illustrate how features of the physical environment interact with physical body issues in recollections of the move decision.

Safety

Safety was the third health and functioning issue. Family members who helped with the move were more likely than elders to talk about safety issues. For example, Mabel Connor does not drive, and her son Paul was uncomfortable with his Dad’s driving to and from cancer treatments. When an elder did mention a safety issue, it was in the context of acknowledging a family member’s worries, as one man stated, “My daughter was concerned about me being alone and falling down stairs.” Sometimes, the children felt a safety issue was so serious that they had no choice but to convince their parent to move. This was the case with Karen and Teresa, who pressured their mother, Linda Brierton, to move for safety reasons:

Mom started hearing things, hearing noises at night, which meant someone was knocking on her door. So in the middle of the night she would get up and see who was there. . . . the fact that she would just go open the door at night was not a good thing. So it was all these little things. She was there by herself. She had to walk down the stairs. The lighting wasn’t good and the place was not in real good shape and there was no security.

The one area where both elders and family members talked about safety was falls. This included the availability of someone able to assist in case of a fall. A husband, whose wife “had three falls that were serious” explained, “She is heavier than I am and I told her, ‘This is one factor, I can’t physically help you.’” Another woman, who lived by herself, described her fall:

I started out the front door with two bags of trash and I fell on the porch, and I couldn’t get up. So, I finally got the attention of a man across the street. I didn’t even know him—and I asked him if he could help me up and he couldn’t lift me. I said, ‘You let me go up as far as I can.’ And he did and I got up. But, I could no longer stay by myself. There was nobody around to pick me up or to help me and there was no way I could get any help. I just couldn’t stay there.

New Beginnings

Some of the reasons to move resulted from individual beliefs or attitudes that created a pressure toward residential mobility. Some respondents saw the move as a new beginning, while others saw it as inevitable. Lifestyle changes accompanied many moves. These took the form of new activities with a sense of adventure, or as an escape from dissatisfaction with current circumstances. One woman described what she and her husband were looking for in a new house, “He wanted a little bit of a yard, that’s his thing. I wanted a large enough house to have the kids home and have my clubs come and meet.” Another woman expressed a newfound sense of freedom, “I now can leave and have nothing to worry about. We all went to Italy just after I moved in.”

Karen, Linda Brierton’s daughter, noted that her mother made the move, in part, to escape her current situation, when she observed her mother as “. . . wanting to be someplace different because she is not happy with her life.” Some who moved wished to disengage themselves from their social roles in the community and embark on adventures involving new roles. One couple, who were well-known in a small, rural town for their community volunteer work explained: “We volunteered a lot, well I did. (Spouse: Well, I did, too!) Yeah. And it really got to be kind of a burden.”

Inevitable Move

Many of the people who moved held the individual belief that the move was inevitable; these residential mobility decisions were proactive. One man adamantly stated, “There really wasn’t any question about it. It was just deciding when. . . .” Several people felt that “it was time” for the move. One husband told us, “I was rather insistent that it was time. We needed to do this and we were gonna have to do it and would be easier if we did it now.” These respondents seemed to anticipate a point in time when they could no longer function independently in their physical home environment.

Closely tied to the idea that it was time to move, were assumptions and expectations related to the aging process. Susan Landers, who moved to a smaller house with her husband, said, “You just have to pull yourself up short every so often and think really how old you are.” Family members shared these assumptions, as one daughter said of her parents’ decision to move, “They realized their age.” Some elders linked the move to a specific age (usually age 85). One woman held this type of age-related expectation:

I had to carry my groceries and things up two flights of stairs. So that’s why I moved out of there when I was 75. And then I decided when I was probably about 85 I would move into something like this sort—when I could still do it and make my own decisions.

Some people, such as the quote above illustrates, implied an impending vulnerability that comes with aging. These people chose residential mobility as a proactive measure to avoid future problems and some saw this move as one in a series of impending moves that one man seemed to perceive as a downward spiral:

When we have to take the next step down into an apartment, I think we will be ready for that then. We are still in good physical condition and health, which is one reason we wanted to move now. So we could take charge of the situation. I think some people wait too long to make this move.

Not everyone felt the move was inevitable. One woman had been planning to age in place. She said, “I fixed up my home, thinking I would live there the rest of my life. But, I had fallen and that wasn’t possible. I just couldn’t stay there.”

Some of these statements show a consciousness of approaching mortality, as Steve Lander’s description of the household disbandment that accompanies a move illustrates, “The children took what they wanted . . . those are not things they will have to go through when we die or when we move to another level of care.” One woman viewed the move as ending one phase and beginning another phase of her life, one that she perceived as liminal to mortality. She felt confident that this move was the right thing for her to do, but still found the changes difficult. Taking out the final bag of trash symbolized the turning point in the transition:

The last time I went back to my house, to take my last batch of trash out, I cried a little bit on the way back. Because that was over. And that’s a little disheartening, because I felt that this was my last move.

Several elders felt strongly that the move needed to be done to reduce their children’s future caregiving tasks. Steve Landers explained, “I suppose it came to this realization when we took care of parents (four parents, two uncles, an aunt) for about 30 years. And we said, ‘We are not going to do this to our children.’” The phrase “if I went down” appeared in more than one interview. For example, Leota Jackson used this expression when she talked about the practical aspects of moving, “I wanted to leave my children free to live their lives and I knew that if I went down that it would be a lot harder for them to sell the mobile home.”

House and Yard

Some reasons to move referenced the physical environment which included the physical layout and size of the house and yard, and proximity of the home to amenities and family. Some issues with the house and yard were a desire to “get down to one level,” the condition of the home and neighborhood, or loss of a spouse who had shared the work of upkeep and maintenance. The home’s condition, need to remodel, or simply wanting to downsize were residential mobility motives, with the burden of house and yard maintenance cited most often. Genevieve Stadel felt that it was “too much house and garden to take care of. Especially after Harold passed away.” Coming to this conclusion was difficult and a source of stress for many people. Genevieve’s son, Will also felt that maintaining the house was too much for his mother to handle after his father died, and he recognized the difficulty of this realization for her when he said, “I think it is hard to admit that you can no longer maintain a house like that.” Some people hired out work as an option, but others found that to be a hassle, as one woman explained:

The house needed someone to do little maintenance things and my son didn’t have time. And to hire someone is difficult. . . . then the yard was beginning to be a problem and it’s expensive for someone to care for it. It was a constant worry. And I like to go places and I now can leave and have nothing to worry about. No yard.

Others didn’t mind some yard work, but wanted to cut back a bit. One man explained, “At 85 years old I don’t want to care for a big yard. We have a yard here [new home], six or seven minutes, I got it mowed.”

Proximity

Another aspect of the physical environment theme is proximity to amenities and family. When Harold was diagnosed with lung cancer, Mabel Connor remembered thinking, “we better get to town” and her son, Will, said, “I know Dad rests better knowing that Mom is in town. She can walk to the pharmacy, to the grocery store, to the bank. It’s all right there.” The move also placed his parents closer to health services, which made family caregiving easier. Will explained, “My sister was transporting them everyday to the hospital. . . .” Proximity moves to ease transportation issues were mentioned by others as well. Leota Jackson was proactive in her reasoning as she anticipated a point when she would no longer drive, “I figured it was time I moved into a place to be more independent and yet not having to drive. Better to be practical.”

Some of the moves relocated parents in closer proximity to their children. One son and his sisters wanted their mother to live near one of them, “We began trying to convince her to move near one of us, and my wife and I won out.” For the Brierton family, Karen and Teresa were not only pleased that their mother had easy access to transportation in her new place, Karen discussed how the remote location of the previous home jeopardized her mother’s social life and independence to come and go when she pleases:

She was isolated. She doesn’t drive, there was no one else around. She was totally dependent on me to come by for company or any kind of transportation. It was not good. This is much better. There are people, the environment is secure, people here keep an eye on each other. They are pleasant. She has access to the bus.

Social Roles

Society imposes social roles upon individuals of all ages, and in turn, these roles create social pressures in the decision-making process. For many of the older adults in our study, the move occurred in conjunction with a life event that instigated changes in social roles for both the mover and their family members. Social roles discussed by elders in our sample included a new marriage, community service, and work. Social roles relevant to residential mobility experienced by their family members were that of family caregiver and work. Several people talked about a spouse who had died within the past one to two years and these moves were often integrated with the transition into widowhood. Will Stadel described how his mother’s move to a retirement community was a continuation of previously made plans that had been interrupted by the death of his father, “They had looked at this retirement community when Dad was still alive. But they hadn’t made any decisions yet. After Dad passed away . . . she decided to start looking, especially at this place.” Some couples began planning for the transition into widowhood together. Paul Connor described how plans to move evolved after his dad was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer: “Knowing that Mom is totally dependant on him he finally agreed to move to town, . . . they hung on to the house until after Dad passed. And once he was gone, Mom went ahead and sold the house.”

Other changes in social roles occurred less frequently, but still had a profound influence on move decisions. One woman told us she started thinking about moving “when I got married” (at age 70!). Some of the people interviewed were in partial retirement and held jobs. One man had relied on this source of income and explained, “I started thinking about moving when I lost my job.” Grandchildren were also a draw, as a grandfather explained, “We would be coming here to take care of the grandkids. My wife was getting tired of driving back and forth with an old man [laughs] and she misses them. That’s why we made the move.”

Family members’ social roles, particularly that of emerging caregiver, also contributed to the move decision. The family members we interviewed were an integral part of these moves through the amount of work they contributed. The family members’ roles in household disbandment may have been a step in the child’s evolution into a caregiver role (Ekerdt & Sergeant, 2006). This study involved community-based moves, so all of the respondents were able to live in their own homes and family members were not caregivers in the sense of providing intimate personal care support. However, several provided assistance with instrumental activities of daily living such as housecleaning or yard work. Karen cleaned her mother’s house, and thus felt a vested interest in how Linda Brierton’s new apartment was set up: “I want things to be sparse. I wouldn’t be comfortable there, but she is. . . . So when she moved, we had to compromise so that she felt comfortable and I could live with how her apartment was.” Leota Jackson’s move was instigated when her daughter’s husband changed jobs and she realized her daughter would no longer be available for informal caregiving, “I knew my daughter and her husband would be moving to Arizona . . . . So I started planning for the move.”

Friends

Friends and acquaintances who had moved served as positive role models and were a component of social pressure in respondents’ move decision processes. Steve and Susan Landers described how friends encouraged them to move into their retirement community, “We visited back and forth and we saw her town home and that planted the seeds.” Karen and Teresa discovered that their mother’s friends at the apartment complex had spoken to Linda Brierton, “And they wanted her to move.”

Finances

Money was a social pressure in several moves. Sometimes, finances were a positive side effect of a move that was primarily made for other reasons. Some elders mentioned that the new house was a “good investment” or that in the new place “the expenses are a lot less here.” Others found themselves in a situation where finances forced a move. One man explained that “the taxes began to overcome us,” and a woman who moved into a low-income apartment said, “I had the choice of being homeless, or living with one of my kids or I have a friend who used to work here part-time and she told me about this place.”

Housing Options

The elders we interviewed moved into a wide variety of housing types including smaller houses, assisted living, low income housing, and continuing care retirement communities. The existence of a range of options becomes part of the social pressure to relocate. At the societal level, the need for services as described in the interviews (i.e., nursing care, transportation, security, daily monitoring, meals, and maintenance) leads to the development of housing alternatives. These social structures may, in turn, reinforce aging expectations held by elders and family members. A woman who moved with her husband to a retirement community explained how an advertisement for their new residence prompted her to bring up the idea of a move, “I saw the ad for this place in June or July and cut it out and put it on my desk and kept it for about three weeks before I took it to Charles.” Different housing environments interact with physical body issues to encourage a move decision toward better environmental fit (Ekerdt & Sergeant, 2006; Lawton, 1982). One couple in our study explained, “. . . the continuing of care though [sic] was a real consideration.”

Waiting lists for housing options that target the elderly played a dual role in decision-making. On the one hand, the waiting list obliged or pressured a move. Will Stadel explained: “Once she knew a unit was available she felt like she should go ahead and reserve it and put the house up for sale.” On the other hand, waiting lists sometimes delayed a desired move. Leota Jackson, who was making the move to avoid functional limitation constraints and placing an undue caregiving role on her children, found the waiting lists frustrating, “So I put my name in here and it took two years to get a one-bedroom apartment.”

Evaluation of the Move

Elders and family members offered evaluative comments about the move and household disbandment throughout the interview. This provided post-move perceptions of the stress and benefits they associated with the move decision, household disbandment, actual move, and post-move adaptation. Table 2 reports examples of positive and negative comments from elders and their family members.

Table 2.

Positive and Negative Descriptions of the Move and Household Disbandment

| Negative | Positive | |

|---|---|---|

| Elder | “It’s been so hard on me.” “very upsetting” “loved the [former place]” “everything is gone” “broke my heart” “don’t know what happened to it” “really hurt me” “hated to move” |

“huge help” “fun” “love . . . [aspect of new home]” “I like little houses better” “I have great ambition for this house” “consistent worry” (former place) “great to be here” |

| Helper | “extraordinarily draining” “responsibility placed on my shoulders” “It was getting ugly” “I felt stuck” “needed counseling” “I feel like I’m a bitch” “furious” “trying to recover from the effort” “horrible” |

“such a huge relief” “Mom was a trooper” “able to make the place feel like home” “wonderful” “she has a blast” “she loves it” “having a great time” |

During the interviews, elders’ descriptive comments often referred to psychological difficulties of the move, yet they were able to reframe the experience into positive comments about certain aspects of the process and feeling comfortable in their new home. Elders’ negative comments described emotional difficulty and disruption of their possessions. Family members, on the other hand, still seemed to be recovering from their ordeal. Their positive comments described how the elder benefited from the move, while their negative comments focused on the difficulties they had with the process—often in vividly dramatic terms. One helper felt “stuck” and made a total of 51 negative comments compared to two positive; in another instance, a daughter described the process as “draining,” making no positive comments at all. Helpers’ negative perceptions included amount of physical work, added responsibility, and juggling the work with their daily lives. The helpers were more likely to discuss the actual physical labor that they undertook, as one daughter who was the impetus behind her father’s move described, “Every week, I would work all week, and then go every weekend, Saturday and Sunday for hours.” The psychological strain on some family members is yet another justification for the inclusion of these players in studies of the late-life residential mobility process.

DISCUSSION

Residential Mobility Motives

This study located motives for late-life residential mobility within ecological layers of the aging context, including individual health and functioning, individual beliefs and attitudes, the physical home environment, and social pressures. Findings suggest that this is a recurrent process rather than a linear one. Even as a behavior is acted upon (to make a residential move), the aging context continually interacts with older adults, instigating a constant process of evaluation and re-evaluation of the “fit” between the home environment and its capability to support one’s independence and quality of life. The model also ties together elder and family member roles in the late-life residential move decision.

Consideration of family experiences illustrates the cumulative effect of residential move motives, which in turn stimulates personal agency to act on strategies to move. For example, changes in health and functioning (e.g., adverse health event), often results in temporary or ongoing caregiving from a spouse, daughter, or son. Individual beliefs about the inevitability of a late-life move and social pressures stemming from the attractiveness of housing options marketed to elders may induce a move to a new home that is closer to services or more accessible. The physical environment (e.g., stairs, proximity to services) may be a barrier to remaining in the home. The common result in all cases represented here was a decision to relocate and the initiative to act upon this decision.

The inclusion of the family perspective was a key element in this study, and results point to the integration of extended family issues with the decision process, family roles, and post-move evaluation. Late-life mobility decisions are often made within the social structure of extended family. Daughters and sons who felt they needed to pressure their parent to move made statements that indicated they felt guilty about doing so, yet their parents did not seem to resent their children’s actions or even feel they were unduly pressured. These perceptions parallel Weigel and Weigel’s (1993) findings that older parents perceived less conflict and greater satisfaction with communications with their children while sons and daughters-in-law reported more problems. Hummert and Morgan (2001) suggest that family decision-making experiences will tend to be more positive when adult children take on an information-gathering role and defer to parents to make the final decision. The elder-helper groups in this study seemed to follow this pattern, and this could partially account for the minimal amount of conflict in descriptions of the move and household disbandment process. However, another explanation is that study respondents did not want to “air dirty laundry.” In this sample of elders who made a community-based move, the decision itself was attributed to the person(s) who moved, but this may not be the case with moves to institutionalized settings such as a nursing home.

Changing roles within the context of a transition involve interactions between social structures and individual agency (Connidis & McMullin, 2002; George, 1993). Within the circumstances leading to late-life residential mobility, changing roles and power structures within the family may be challenged, which in turn shapes reasons for the move. For example, interdependent roles (e.g., within a marriage), allow couples to manage responsibilities (e.g., high maintenance home) that would not have been possible for one person acting alone. If one of the parties is no longer able to fulfill his or her role due to illness or widowhood, independence may be threatened and residential mobility emerges as a solution. For extended family, caregiving adds responsibilities to family members who willingly accept or discourage this role, and in this study, the desire to avoid placing caregiving responsibilities on their family members was cited by elders as a motive for moving. Competing factors are at play here. Family members receive benefits such as peace of mind regarding safety concerns, emotional benefits, filial responsibility, and altruism through informal caregiving tasks (Eggebeen, 2002; Lewinter, 2003; Silverstone & Horowitz, 1992), whereas time issues or social structures (e.g., work) discourage fulfillment of this role. In addition, informal caregiving may alter traditional patterns of interaction across family members (Hummert & Morgan, 2001). This sets up a paradox wherein the elder and family members prefer to maintain existing family structures and roles, yet functional limitations and even caregiving tasks threaten the status quo. Demands on family members’ time and reluctance by either party to take on new roles may compel a move to a more accommodating housing environment that allows the family to maintain its social structure for a period of time.

Inclusion of the family perspective in this study revealed divergence in post-move evaluations of the process and outcome, as well as an indication of the anguish that often accompanies the process. In this study, elders and their family members described numerous negative aspects to the move and household disbandment, often expressing these in vivid terms. Elders were able to reframe the move into a positive transition, while family members who helped with the move were slower to be positive. They still seemed to be recovering from the process, although they did describe how the move was beneficial to their parents. While family members are not an integral part of all late-life moves, an analysis of residential mobility solely from the perspective of the elder only captures part of the story.

Future Directions

This study is limited to post-move perspectives of those who made a decision for residential mobility. It is also important to consider decision processes that result in a non-move via aging in place or home modifications. Additional knowledge is needed to better understand late-life residential mobility expectations prior to the move decision, the residential move experiences of more diverse populations, and the effect of socio-demographic characteristics of both the individual and family members on these decisions.

Dimensions of decision-making related to individual health and functioning, individual beliefs and attitudes, physical environment, and social pressures have applied relevance to other significant late-life decisions such as undergoing hip replacement surgery or relinquishing driving. The residential mobility decision described here instigated an environmental change to address physical body, internal expectations, and external pressures. A decision to have a hip replacement instigates a physical body change conceivably to address physical environment, self-identity, and external pressures. And a decision to give up driving relinquishes a social role as a driver to address physical body issues and has tremendous implications for the boundaries of one’s milieu, social network, and self-identity. The aging context related to the individual, family, neighborhood, and community are important factors to consider in these studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jaber Gubrium, Molly Dingel, Mary Elizabeth Bowen, Jennifer Hackney, Maryann Muncy, and Marit Genero for their assistance with this study. A portion of this article was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Orlando, Florida, November 2005.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, AG19978, and support from the Madison and Lila Self Graduate Fellowship Program, Lawrence, Kansas.

REFERENCES

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Evandrou M. Ageing, independence, and the life course. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; London, UK: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer AH, Harper L. Fixing to stay: A national survey of housing and home modification issues. AARP; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Butrica BA, Wasylenko MJ. Mobility patterns of older homeowners: Are older homeowners trapped in distressed neighborhoods? Research on Aging. 1995;17:363–384. [Google Scholar]

- Chen PC, Wilmoth JM. The effects of residential mobility on ADL and IADL limitations among the very old living in the community. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S164–S172. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevan A. Holding on and letting go: Residential mobility during widowhood. Research on Aging. 1995;17(3):278–302. [Google Scholar]

- Colsher PL, Wallace RB. Health and social antecedents of relocation in rural elderly persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1990;45(1):S32–S38. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.1.s32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA, McMullin JA. Sociological ambivalence and family ties: A critical perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:558–567. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman LT. Retirement and family relationships: An opportunity in later life. Generations. 2002;26:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen D. Intergenerational exchanges. In: Ekerdt DJ, editor. Encyclopedia of aging. Vol. 2. Macmillan Reference; New York: 2002. pp. 724–726. [Google Scholar]

- Ekerdt DJ, Sergeant JF. Family things: Attending the household disbandment of elders. Journal of Aging Studies. 2006;20:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekerdt DJ, Sergeant JF, Dingel M, Bowen ME. Household disbandment in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S265–S273. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth CA. Aging bodies: Images and everyday experience. AltaMira Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BJ. The stigma of relocation to a retirement facility. Journal of Aging Studies. 1990;4(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Sociological perspectives on life transitions. Annual Review of Sociology. 1993;19:353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Morgan M. Negotiating decisions in the aging family. In: Hummert ML, Nussbaum JF, editors. Aging, communication, and health: Linking research and practice for successful aging. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy D, Sylvia E, Bani-Issa W, Khater W, Forbes S. Beyond the rhythm and routine: Adjusting to life in assisted living. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2005;31:17–23. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirlik A, Strauss R. Medical uncertainty and the older patient: An ecological approach to supporting judgment and decision making. In: Rogers WA, Fisk AD, editors. Human factors interventions for the health care of older adults. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In: Lawton MP, Windley PG, Byerts TO, editors. Aging and the environment: Vol. 7, Theoretical approaches. 1st ed. Springer; New York: 1982. pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinter M. Reciprocities in caregiving relationships in Danish elder care. Journal of Aging Studies. 2003;17:357–377. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Hawley PH, Henrich CC, Marsland KW. Three views of the agentic self: A developmental synthesis. In: Deci EL, Ryan RM, editors. Handbook of self-determination. University of Rochester Press; Rochester, NY: 2002. pp. 389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E, Longino CF. Migration patterns among the elderly: A developmental perspective. The Gerontologist. 1987;27:266–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longino CF, Jackson DJ, Zimmerman RS, Bradsher JE. The second move: Health and geographic mobility. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1991;46:S218–S224. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.4.s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack R, Salmoni A, Viverais-Dressler G, Porter E, Garg R. Perceived risks to independent living: The views of older, community-dwelling adults. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:729–736. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox GL. Housing and living arrangements: A transactional perspective. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 5th ed. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2001. pp. 426–443. [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J-S. The “Casser Maison” ritual. Journal of Material Culture. 2001;6:213–235. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Designing a qualitative study. In: Rog DJ, Bickman L, editors. Handbook of applied social research methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 69–100. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JW, Speare A. Distinctively elderly mobility: Types and determinants. Economic Geography. 1985;61:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Home Builders . Housing: Facts, figures, and trends. National Association of Home Builders; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Netting FE, Wilson CC. Accommodation and relocation decision making in continuing care retirement communities. Health and Social Work. 1991;16:266–273. doi: 10.1093/hsw/16.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . Using NVivo in qualitative research. QSR International; Melbourne, Australia: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM. Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality. 1995;63:397–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Angelelli JJ. Older parents’ expectations of moving closer to their children. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B:S153–S163. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.3.s153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Zablotsky DL. Health and social precursors of later life retirement-community migration. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1996;51B:S150–S156. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.3.s150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone BM, Horowitz A. Aging in place: The role of families. Generations. 1992;16(2):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smider NA, Essex MJ, Ryff CD. Adaptation to community relocation: The interactive influence of psychological resources and contextual factors. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:362–372. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speare A, Avery R, Lawton L. Disability, residential mobility, and changes in living arrangements. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1991;46:S133–142. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.3.s133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulle E, Mooney E. Moving to ‘age-appropriate’ housing: Government and self in later life. Sociology. 2002;36:685–793. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C, Hobson S, Melles P, Kloseck M, Vandervoort A, Crilly R. Falls and fear of falling among community-dwelling seniors: The dynamic tension between exercising precaution and striving for independence. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2004;23:307–318. doi: 10.1353/cja.2005.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel DJ, Weigel RR. Intergenerational family communication: Generational differences in rural families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RF, Roseman CC. A typology of elderly migration based on the decision-making process. Economic Geography. 1979;55:324–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey JL, Angel RJ. Functional capacity and living aRangements of unmaRied elderly persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1990;45(3):S95–101. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.s95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]