Abstract

A serious complication of current protein replacement therapy for hemophilia A patients with coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) deficiency is the frequent development of anti-FVIII inhibitor antibodies that preclude therapeutic benefit from further treatment. Induction of tolerance by persistent high-level FVIII synthesis following transplantation with hematopoietic stem cells expressing a retrovirally-delivered FVIII transgene offers the possibility to permanently correct the disease. Here, we transplanted bone marrow cells transduced with an optimized MSCV-based FVIII oncoretroviral vector into immunocompetent hemophilia A mice that had been conditioned with a potentially lethal dose of irradiation (800 cGy), a sublethal dose of irradiation (550 cGy) or a nonmyelablative preparative regimen involving busulfan. Therapeutic levels of FVIII (42%, 18% and 11% of normal, respectively) were detected in the plasma of the transplant recipients for the duration of the study (over 6 months). Moreover, subsequent challenge with recombinant FVIII elicited at most a minor anti-FVIII inhibitor antibody response in any of the experimental animals in contrast to the vigorous neutralizing humoral reaction to FVIII that was stimulated in naive hemophilia A mice. These findings represent an encouraging advance toward potential clinical application and long-term amelioration or cure of this progressively debilitating, life-threatening bleeding disorder.

Keywords: hemophilia A, factor VIII gene therapy, oncoretroviral vector, hematopoietic stem cells, bone marrow transplantation, transgene-specific tolerance induction

INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia A is an X-linked recessive bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency or functional defect in coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) [1]. Hemorrhagic episodes can be prevented or treated by intravenous injection of plasma-derived FVIII concentrates or recombinant FVIII protein. High cost and unpredictable shortages of recombinant FVIII and risk of transmission of blood-borne viruses (historically, hepatitis A, B and C, HIV and B19 parvovirus) with plasma-derived FVIII are among the disadvantages of protein replacement therapy. In addition, due to a relatively short half-life of FVIII in the circulation (12−14 h), prophylactic treatment of hemophilia A requires repeated administration of FVIII preparations. Consequently, the use of central catheter lines is often required for venous delivery of FVIII, especially among children, and these devices are frequently associated with infection and thrombosis. Finally, a very serious complication of this treatment is the development of neutralizing “inhibitor” antibodies against FVIII in up to 30% of hemophilia A patients, rendering them unresponsive to further FVIII protein infusions [2].

Hemophilia A is an excellent candidate for gene therapy because it is a monogenic disorder and modest elevation of FVIII levels to a few percent of normal is sufficient to significantly improve the clinical symptoms. Moreover, tissue-specific expression of transgenic FVIII is not required, only that the protein is secreted into the bloodstream [3, 4]. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are an attractive target cell population for hemophilia A gene therapy because they are readily accessible for ex vivo genetic modification and allow for the possibility of sustained expression of a FVIII transgene in circulating peripheral blood cells for the lifetime of the patient following bone marrow transplantation [3]. Retroviral vectors (which include those derived from oncoretroviruses and lentiviruses) have been widely used for both experimental and clinical HSC gene therapy studies because they integrate into chromosomal DNA and are therefore stably transferred during HSC self-renewal and differentiative cell divisions [5]. Using a murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-derived oncoretroviral vector encoding a secretion-enhanced B domain-deleted (BDD) human FVIII transgene (sfVIIIΔB), we previously reported successful HSC gene therapy-based correction of hemophilia A in a sublethally irradiated (550 cGy) murine bone marrow transplant model [6]. Although the study demonstrated the potential of this treatment modality as a curative therapeutic strategy for hemophilia A, the utilization of an immunocompromised hemophilia A double knockout mouse strain (E16/B7−2−/−, containing targeted disruptions in exon 16 of the FVIII gene and in the B7−2/CD86 T cell costimulatory molecule gene) [7] precluded us from addressing the issue of whether an inhibitor response might eventually develop against the sfVIIIΔB-encoded protein in transplant recipients having normal immune systems.

A potential benefit of targeting HSCs for hemophilia A gene therapy is the possibility of inducing immune hyporesponsiveness and, ideally, stable long-term tolerance to an expressed transgene product [8-16]. In particular, Evans and Morgan reported that up to 50% of lethally (900 cGy)-irradiated hemophilia A mice were tolerized to human FVIII following transplantation of bone marrow cells transduced with human BDD-FVIII-encoding oncoretroviruses, even though FVIII plasma levels were below detection [11]. Here, we transplanted bone marrow cells transduced with the same oncoretroviral vector we used previously – MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP, expressing the sfVIIIΔB transgene and the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter gene – into immunocompetent E16 hemophilia A mice (FVIII exon 16 knockout mice on a C57BL/6 background) which are known to generate a potent inhibitor response against human FVIII [17-20]. For comparison purposes, the mice were conditioned with either 550 cGy or 800 cGy total body irradiation, or alternatively a more clinically acceptable nonmyeloablative dose of busulfan [21].

RESULTS

Correction of the Hemophilic Phenotype in FVIII Knockout Mice

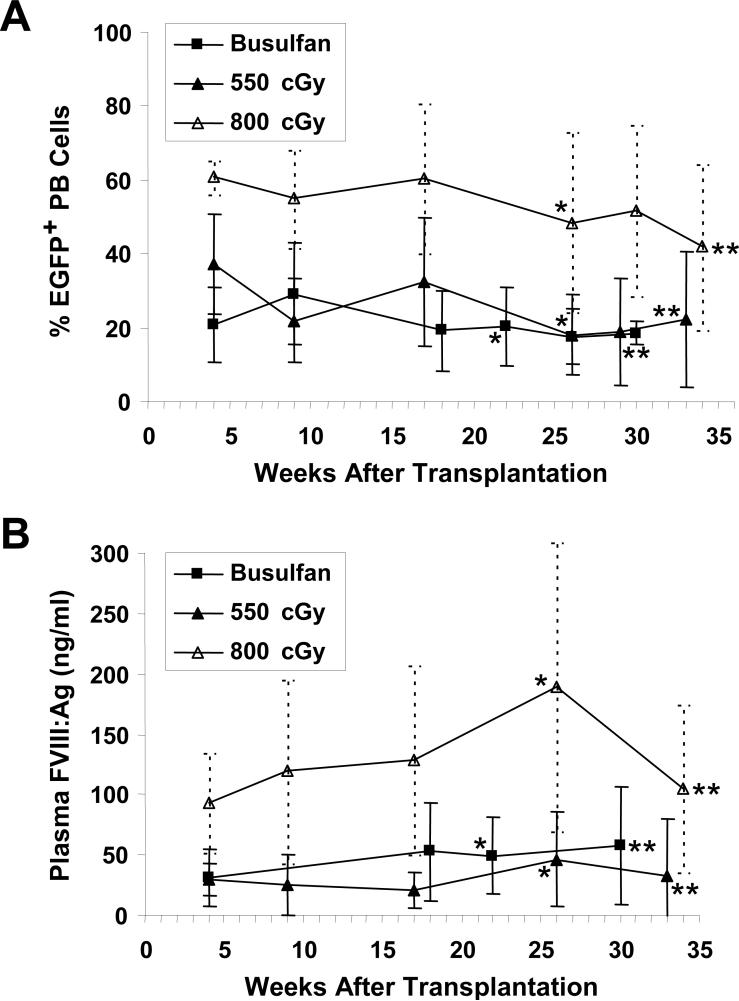

We transplanted three groups of E16 hemophilia A mice with bone marrow transduced with the MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP oncoretroviral vector [6]. The first group of mice received a sublethal dose of 550 cGy total body irradiation, identical to the dose we used previously in experiments performed with immunocompromised E16/B7−2−/− hemophilia A animals [6]. In a second group, the mice received a higher dose of irradiation (800 cGy), which was predicted to allow improved engraftment and result in tolerance to sFVIIIΔB in at least a fraction of the recipient mice based on the Evans and Morgan results [11]. Both groups of irradiated mice were transplanted with 2 × 106 sorted EGFP+ bone marrow cells. All of the mice engrafted successfully, demonstrating donor chimerism for the entire duration of the study. At 26 weeks, 18 ± 11% (n = 12) and 48 ± 24% (n = 10) EGFP+ nucleated peripheral blood cells were detected in mice conditioned with 550 and 800 cGy irradiation, respectively (Fig. 1A). A third group of four mice received a nonmyeloablative busulfan-based conditioning regimen previously shown to allow stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism sufficient for tolerance induction to EGFP [21]. The busulfan-treated mice were transplanted with either 15 × 106 or 20 × 106 transduced unsorted bone marrow cells (of which mouse BU1 received 11.6 × 106 EGFP+ cells and mice BU2-BU4 each received 8.4 × 106 EGFP+ cells). Mouse BU2 died at 4 weeks posttransplant due to an unknown cause. The reconstitution kinetics of the remaining three engrafted busulfan-conditioned mice was very similar to the group of mice conditioned with 550 cGy irradiation, and 18 ± 7% of their nucleated peripheral blood cells were EGFP+ at 26 weeks posttransplant (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

EGFP+ cells in peripheral blood and plasma FVIII levels in sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice. (A) Shown is the percentage of EGFP+ nucleated peripheral blood (PB) cells in the three groups of E16 hemophilia A mice that received MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced bone marrow cells as determined by quantitative flow cytometric analysis at various time points posttransplant. (B) Human FVIII antigen (FVIII:Ag) levels in the plasma of each of the three groups of sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice measured by ELISA and presented as average ± SD. Corresponding data obtained before the first (*) and 1 week after the seventh (**) injection of recombinant FVIII are indicated on each graph.

Using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for human FVIII antigen (FVIII:Ag), high levels of sFVIIIΔB were detected in the plasma of all sfVIIIΔB gene-treated E16 hemophilia A mice at every time point evaluated (Fig. 1B), whereas no FVIII:Ag was detected in naive E16 mice (data not shown). The FVIII:Ag levels detected in all three groups of treated mice corresponded to the relative expression of EGFP in their peripheral blood cells (Fig. 1A and B).

We previously determined that plasma from normal C57BL/6 mice contained 680 ± 140 mIU/ml human FVIII activity equivalents using a chromogenic assay (COATEST® VIII:C/4) [6]. In the COATEST assay, FVIII acts as a cofactor to accelerate activation of factor X by factor IXa in the presence of calcium and phospholipids. Factor Xa then hydrolyzes a chromogenic substrate and the intensity of the resulting color, which is proportional to FVIII activity, is determined. Based on this two-stage assay, evaluable E16 recipient mice that had received MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced bone marrow cells following busulfan conditioning, 550 cGy irradiation or 800 cGy irradiation had 11% (74 ± 72 mIU/ml; n = 2), 18% (124 ± 82 mIU/ml; n = 6) and 42% (288 ± 241 mIU/ml; n = 9) of wild-type murine FVIII levels, respectively, in their plasma 22−26 weeks posttransplant. As predicted from our previous study [6], when we clipped the tails of the three mice in the busulfan-conditioned group and two animals (mice #26 and #27) from the 800 cGy-irradiated group, all five sfVIIIΔB gene-treated E16 animals exhibited clot formation and survived this stringent coagulation assay, documenting phenotypic correction of their hemophilic phenotype. In contrast, none of four naive E16 hemophilia A mice survived tail clipping, dying from exsanguination within 12 h.

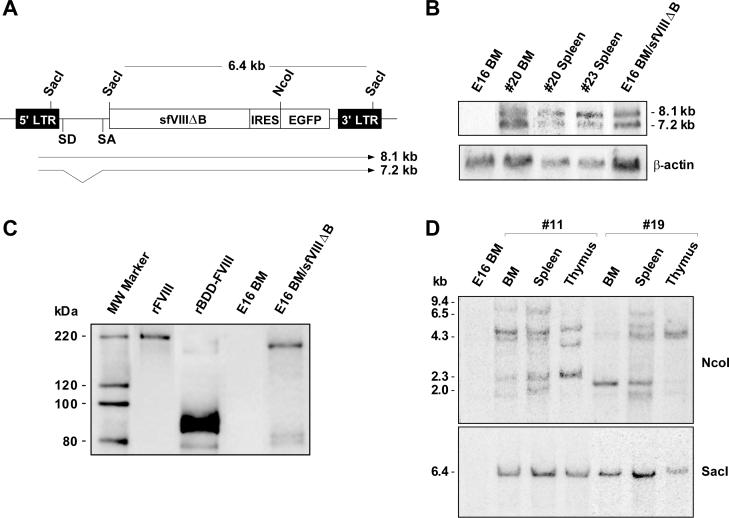

When total RNA isolated from bone marrow and spleen cells of two sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice from the 800 cGy-irradiated group (mice #20 and #23) was subjected to Northern blot analysis using an EGFP-specific probe, two major transcripts corresponding to the full-length vector RNA (8.1-kb band) and spliced sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP mRNA (7.2-kb band) (Fig. 2A) were present as expected (Fig. 2B) [6]. Western blot analysis for sFVIIIΔB was performed on MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced E16 bone marrow cell lysates, with nontransduced E16 bone marrow cell lysates as negative control and recombinant full-length human FVIII or recombinant human BDD-FVIII as positive controls (Fig. 2C). In the recombinant full-length FVIII control, we detected a single species of approximately 200 kDa representing the FVIII heavy chain; the 80 kDa light chain was not visualized likely due to the low reactivity of the anti-FVIII polyclonal antibody (SAF8C-AP), as observed previously by others [22] and by us in our earlier experiments involving transduced NIH3T3 cells [6]. The rBDD-FVIII positive control was comprised mainly of a 90 kDa heavy chain and a poorly visualized 80 kDa light chain, although very low levels of a 170 kDa single chain product was also detected. As previously observed in transduced NIH3T3 cell lysates [6], lysates from MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced E16 bone marrow cells exhibited a strong band of approximately 170 kDa, demonstrating proper synthesis of the primary sFVIIIΔB translation product representative of BDD-FVIII single chain [22, 23]; a very faint doublet of approximately 80 kDa, representing some intracellularly processed sFVIIIΔB cleavage products, was also apparent (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Detection and expression of MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP vector sequences and clonal analysis of hemophilia A transplant recipients. (A) Schematic representation of the MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP vector indicating the predicted 8.1-kb (full-length vector RNA) and 7.2-kb (spliced sfVIIIΔB/EGFP mRNA) transcripts. Shown are the NcoI and SacI restriction sites used for clonal analysis and assessment of vector sequence transmission, respectively. Abbreviations: LTR, long terminal repeat; sfVIIIΔB, secretion-enhanced B-domain-deleted human FVIII gene; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein gene; SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor. (B) Northern blot analysis of MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP vector transcripts. Total RNA was extracted from bone marrow (BM) and spleen cells from two 800 cGy-irradiated recipients (mice #20 and #23) and from nontransduced and transduced sorted E16 bone marrow (BM) cells. The two expected (full-length and spliced) vector transcripts were detected by hybridization with an EGFP-specific probe. The blot was subsequently rehybridized with a probe specific for β-actin sequences to monitor intactness of the RNA samples. (C) Detection of sFVIIIΔB protein in MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced E16 bone marrow cells. Cell extracts from nontransduced and transduced E16 bone marrow (BM) cells were immunoprecipitated with two light-chain-specific monoclonal antibodies (ESH2 and ESH8), electrophoresed through a 4−12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel under reducing conditions, and blotted onto a PVDF membrane. FVIII proteins were identified with an anti-human FVIII polyclonal primary antibody (SAF8C-AP). Recombinant full-length FVIII (rFVIII) and recombinant BDD-FVIII (rBDD-FVIII) were used as positive controls. (D) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA obtained from bone marrow (BM), spleen and thymus of a 550 cGy-irradiated (mouse #11) and an 800 cGy-irradiated (mouse #19) recipient was digested with either NcoI or SacI and hybridized with an EGFP-specific probe for clonal analysis and determination of vector structural integrity, respectively. The positions of molecular weight size standards (kb) are indicated on the left of the NcoI-digested DNA blot. The 6.4-kb SacI band corresponding to unrearranged sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP sequences is also indicated.

Multilineage Hematopoietic Reconstitution of sfVIIIΔB Gene-Treated Mice

Three (busulfan-conditioned) to four (550 cGy- and 800 cGy-irradiated) animals from each of the three groups of sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice were randomly selected between 13 and 26 weeks posttransplant to analyze the lineage distribution of EGFP-expressing donor cells. Peripheral blood cells were stained with antibodies specific for cell surface lineage markers identifying murine B cells (CD19), T cells (Thy-1), granulocytes (Gr-1) and monocyte/macrophages (Mac-1). EGFP+ cells were detected in all lineages in all cases (Table 1). Moreover, sustained EGFP expression was observed in all cell preparations analyzed from the bone marrow, spleen and thymus of these mice as well as those from all other evaluable animals at time of sacrifice 27−40 weeks posttransplant, consistent with transduction of long-term multlineage repopulating HSCs (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Hematopoietic lineage distribution of EGFP+ cells in sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice

| Conditioning Regimen | PBa | BMb | Spleenb | Thymusb | ||||

| Total | CD19+ | Thy-1+ | Gr-1+ | Mac-1+ | ||||

| Busulfan | 13 ± 5 | 22 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 36 ± 8 | 75 ± 5 | 29 ± 14 | 12 ± 2 | 8 ± 10 |

| 550 cGy | 19 ± 13 | 47 ± 21 | 25 ± 10 | 17 ± 14 | 36 ± 17 | 8 ± 3c | 13 ± 11 | 42 ± 36 |

| 800 cGy | 28 ± 8 | 40 ± 20 | 12 ± 4 | 22 ± 11 | 52 ± 23 | 40 ± 32d | 23 ± 7 | 16 ± 19 |

Values represent average percentages ± SD of EGFP+ cell subsets in the peripheral blood (PB) of three busulfan-conditioned (mouse BU1 at 13 weeks posttransplant, and mice BU3 and BU4 at 18 weeks posttransplant), four 550 cGy-irradiated (mice #4, #5, #7 and #15 at 26 weeks posttransplant) and four 800 cGy-irradiated (mice #22, #24, #26 and #27 at 26 weeks posttransplant) sfVIIIΔB gene-treated E16 mice.

Values represent average percentages ± SD of EGFP+ cells in the bone marrow (BM), spleen and thymus of the same mice at time of sacrifice (29−40 weeks posttransplant).

Average percentage ± SD of EGFP+ cells in the bone marrow of all 550 cGy-irradiated sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice evaluated at time of sacrifice was 12 ± 9% (n = 11).

Average percentage ± SD of EGFP+ cells in the bone marrow of all 800 cGy-irradiated sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice evaluated at time of sacrifice was 47 ± 35% (n = 9).

To examine the clonal composition of the reconstituted hematopoietic systems of sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice, genomic DNA from bone marrow, spleen and thymic tissue of one recipient from each of the 550 cGy- and 800 cGy-irradiated groups (mice #11 and #19 at 29 and 27 weeks posttransplant, respectively) was digested with NcoI, which cleaves at the 5' end of the EGFP gene (Fig. 2A), and Southern blot analysis was performed with the EGFP-specific probe. The vector integration patterns observed indicated that in each case hematopoietic reconstitution was oligoclonal, with the progeny of a few candidate HSCs (as well as lineage-restricted hematopoietic precursors) having repopulated the recipients (Fig. 2D). No attempt was made to determine whether the clonal dominance observed was due to insertional effects [24]. When the same DNA samples were digested with SacI, which cleaves the vector within both long terminal repeats and at the 5' end of the sfVIIIΔB transgene (Fig. 2A), a single 6.4-kb EGFP-specific band was observed in all cases, demonstrating that the integrated sfVIIIΔB transgenes were faithfully transmitted without rearrangement.

Suppression of Immune Response to FVIII in Corrected Hemophilia A Transplant Recipients

Long-term persistence of EGFP+ peripheral blood cells and sustained expression of sfVIIIΔB-encoded human FVIII in the plasma of all immunocompetent E16 hemophilia A bone marrow transplant recipients for more than 6 months posttransplant implied lack of stimulation of a potent inhibitory immune response to FVIII. To confirm this notion, we measured human FVIII-specific antibodies (IgG fraction) in the serum of the mice by ELISA at 18 (mouse BU1), 22 (mice BU3 and BU4) and 26 (all irradiated mice) weeks after transplantation. All except one mouse (BU3) had less than 0.2 μg/ml anti-FVIII IgG antibodies in their serum, similar to naive E16 hemophilia A mice. Mouse BU3 had an anti-FVIII IgG antibody titer (6.2 ± 1.1 μg/ml) at 22 weeks posttransplant. It is worth noting, however, that this mouse had approximately 28% EGFP+ nucleated peripheral blood cells at this time point, indicating absence of a cytotoxic T cell-mediated immune response that would have led to the elimination of MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced cells.

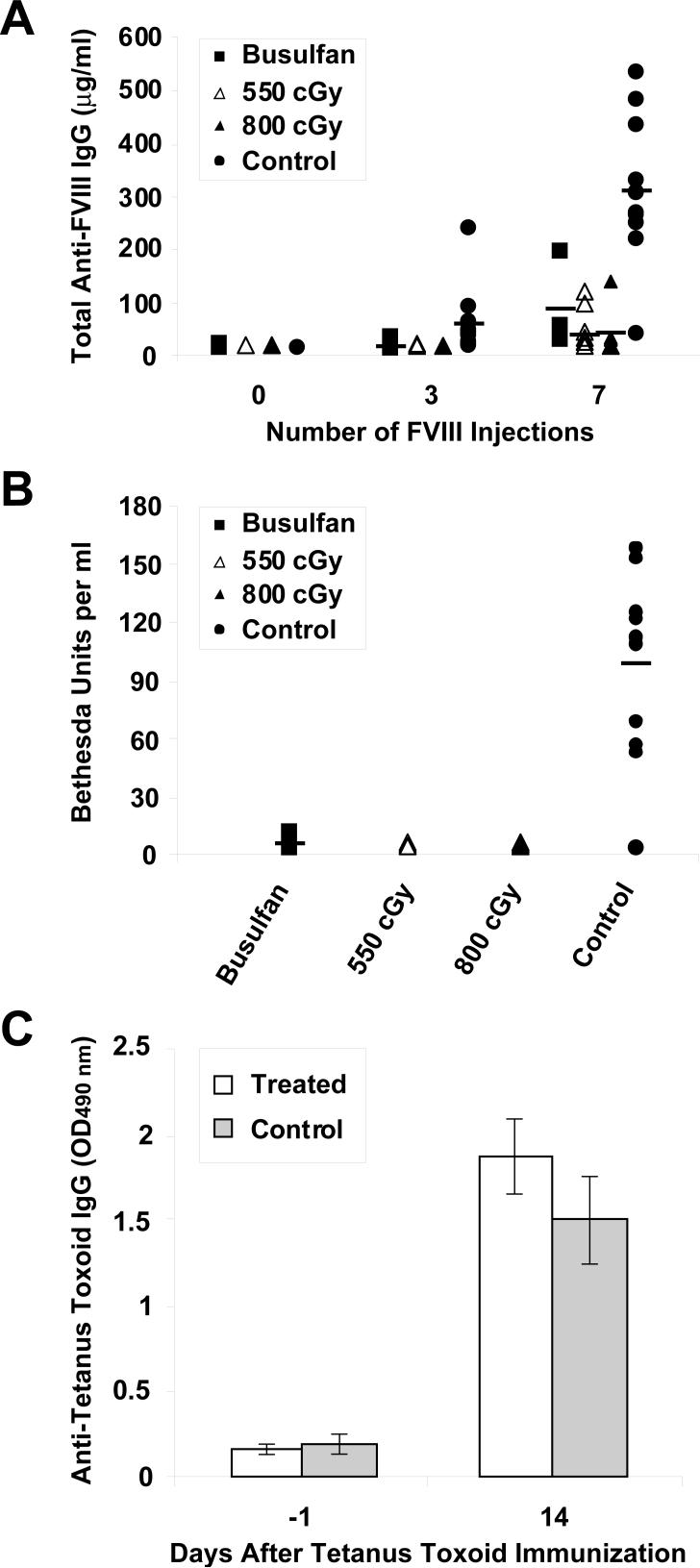

The apparent lack of a strong humoral immune response to FVIII or an overt cytotoxic immune response to sfVIIIΔB-expressing donor cells in 19 of 20 sfVIIIΔB gene-treated bone marrow transplant recipients indicated hyporesponsiveness to the sFVIIIΔB neoantigen. To determine whether the mice were tolerized to FVIII, we challenged the mice with repeated intravenous injections of recombinant full-length human FVIII at weekly intervals (up to eight doses). Eleven age-matched naive E16 mice were also immunized in parallel as a control group. Sera from corrected and control mice were analyzed for the presence of anti-FVIII IgG by ELISA before the first, and 1 week after the third and seventh FVIII injections. While we observed a vigorous humoral immune response to human FVIII in naive E16 mice after seven injections, only low levels of anti-FVIII IgG were detected in some of the sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice receiving the same number of injections (Fig. 3A). There were some outliers in each of the three sfVIIIΔB gene-treated groups; however, the average response in each group was considerably lower than seen in the control mice, indicating significant suppression of the immune response to FVIII. It is important to stress that due to technical considerations (availability of the recombinant protein) the FVIII immunizations and anti-FVIII ELISA were performed with full-length FVIII protein. Since the total anti-FVIII IgG generated presumably included antibodies directed against the B domain, which is not present in sFVIIIΔB, we also determined the inhibitor titers in the plasma of the FVIII-challenged mice, which are based on FVIII functional activity. Fig. 3B shows the inhibitor titer measured by conventional Bethesda assay in all three groups of sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice and in naive E16 mice after the seventh FVIII protein infusion. Significantly higher levels of inhibitor antibodies were detected in the plasma of FVIII-primed control mice (98 ± 48 Bethesda units per ml) compared to the average levels detected in all of the sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice (3 ± 4, 0.7 ± 0.5 and 0.8 ± 0.6 Bethesda units per ml for the busulfan-conditioned, 550 cGy-irradiated and 800 cGy-irradiated groups, respectively). These findings argued that the modest anti-FVIII responses elicited were primarily directed against the B domain of the FVIII immunogen and not against the sFVIIIΔB protein [25, 26].

FIG. 3.

Humoral immune responses in corrected E16 hemophilia A mice challenged with recombinant FVIII or tetanus toxoid. (A) Total FVIII-specific IgG was measured in the serum of busulfan-conditioned (n = 3), 550 cGy-irradiated (n = 10) and 800 cGy-irradiated (n = 6) sfVIIIΔB gene-treated recipients and naive E16 mice (n=11) by ELISA before any FVIII injections, and after three or seven intravenous challenges with recombinant FVIII. (B) Inhibitor titers were measured by Bethesda assay in the same four groups of mice 1 week after the seventh intravenous FVIII injection. Each data point in both the ELISA and the Bethesda assay represents the average of at least two separate determinations. Horizontal lines represent mean values. (C) Two of the 800 cGy-irradiated bone marrow transplant recipients (mice #26 and #27) and four naive E16 mice were immunized with 4 μg tetanus toxoid in adjuvant 3 weeks after the final challenge with FVIII. Two weeks later, the presence of anti-tetanus toxoid IgG was evaluated by ELISA and the values reported as average ± SD of optical density at 490 nm.

Immune Hyporesponsiveness to FVIII in sfVIIIΔB Gene-Treated Bone Marrow Transplant Recipients is Specific

To show that the marked attenuation of the anti-FVIII immune response observed in the sfVIIIΔB gene-treated E16 bone marrow transplant recipients was not due to systemic immunosuppression secondary to busulfan conditioning or irradiation treatment, we immunized two of the FVIII-primed mice from the 800 cGy-irradiated group (mice #26 and #27) that had shown minimal anti-FVIII antibody development after the seventh recombinant FVIII injection (3 ± 1 and 0.2 ± 0.1 μg/ml total anti-FVIII IgG, respectively) with 4 μg tetanus toxoid plus adjuvant 3 weeks after the eighth challenge with recombinant FVIII. Four naive E16 mice were immunized in the same manner. Two weeks after the tetanus toxoid immunizations, anti-tetanus toxoid IgG antibodies were measured in the sera of the mice by ELISA. No significant difference in the immune response to tetanus toxoid was observed between the two corrected mice and the four control animals (Fig. 3C), indicating that humoral hyporesponsiveness to FVIII in the sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice was a specific effect and not due to generalized deficiency of their immune systems.

DISCUSSION

While it had been established by us [8] and others [9-16] in model systems with smaller neoantigens that HSC-directed gene delivery could induce marked immune hyporesponsiveness and in some instances long-lasting immunological tolerance to the transgenic protein, it was unclear whether inhibitor antibody development in hemophilia A could be sufficiently attenuated by this approach to achieve therapeutic efficacy [11, 22, 27]. Encouraged by our prior success demonstrating the potential of HSC-directed FVIII gene transfer as a curative therapeutic strategy for hemophilia A in an immunocompromised hemophilia A mouse model [6], we set out to address this issue in the current study in immunocompetent hemophilia A mice using three different host conditioning regimens. One group of hemophilia A transplant recipients received a minimally myeloablative dose of total body irradiation (550 cGy) as in our previous experiments [6]. In another series, the recipient mice were conditioned with 800 cGy total body irradiation, approaching the lethal irradiation (900 cGy) dose used by Evans and Morgan [11]. Since transplant-related morbidity due to high dose irradiation is not acceptable for treatment of nonmalignant diseases, we decided to also evaluate a low-intensity busulfan-based conditioning regimen more appropriate for clinical gene therapy [28]. For this purpose, a third group of mice received two intraperitoneal doses of 10 mg/kg busulfan, which was previously shown to be nonmyeloablative in C57BL/6 bone marrow transplant recipients that became tolerized to transgenic EGFP [21].

We observed persistent expression of therapeutic levels of sfVIIIΔB-encoded human FVIII in the plasma of E16 hemophilia A bone marrow recipients and the virtual absence of anti-FVIII inhibitor antibodies under all of the above conditions. It is not clear how “molecular chimerism” resulting from expression of a foreign transgene in transplanted bone marrow cells leads to donor-specific tolerance [29]. While it is thought that bone marrow-derived antigen- presenting cells such as dendritic cells and B cells play an important role by processing and presenting transgene-encoded antigenic peptides in the context of self-MHC class II to immature T cells in the thymus [30, 31], more recent studies have suggested that mature T cells derived from donor bone marrow cells expressing a foreign protein may actively participate in transplantation tolerance by re-entering the thymus [32, 33]. In this regard, we showed that the MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP oncoretroviral vector exhibited broad transcriptional activity in cells belonging to both the myeloid and lymphoid lineages in peripheral blood, and in donor-derived cells residing within the bone marrow, spleen and thymus. Irrespective of the mechanism, accumulated data have indicated that the level of in vivo transgene expression is a key determinant whether central tolerance or peripheral unresponsiveness will ensue [34-36]. We previously discussed various aspects of the MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP vector design that permitted sustained high-level sfVIIIΔB transgene expression in the reconstituted hematopoietic systems of bone marrow transplant recipients in a hemophilia A animal model incapable of mounting an immune response to FVIII [6]. Central tolerance would lead to elimination of T cell clones that are reactive to FVIII, whereas peripheral tolerance could be due to persistence of some FVIII-specific clones rendered unresponsive by anergy, ignorance or active suppression by regulatory T cells. While we make no claims as to the nature of the hyporesponsive states elicited in each case, the results obtained in the small cohort of busulfan-conditioned animals are particularly exciting since the experimental protocol more closely approximates a clinically applicable situation, both in terms of a mild conditioning regimen as well as the lack of a preselection step for MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP-transduced bone marrow cells. Moreover, other recent work suggests that transient depletion of T cells and/or costimulatory blockade (with CTLA-4-Ig, anti-CD80/86, anti-CD40 and/or anti-CD154 monoclonal antibodies) as an adjunct component [37] may allow such nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens to achieve the long-term tolerance previously achieved by high-dose irradiation [16].

As noted earlier, it seems reasonable to assume that a significant proportion of the anti-FVIII antibodies that were induced in the sfVIIIΔB gene-treated mice upon repeated challenge with recombinant full-length FVIII were directed against the B domain of the protein, which is not present in sFVIIIΔB. The low levels of inhibitor formation detected in the Bethesda assay are consistent with this interpretation and in accordance with clinical observations showing that anti-FVIII B domain antibodies do not interfere with FVIII activity [25, 26]. In any event, the amount of FVIII that was administered in each dose was 5−10 times higher than would be provided to hemophilia patients in order to bring their plasma FVIII activity to 100% normal levels (≤50 IU/kg or 10 μg/kg). Therefore, even if a true state of tolerance was not induced in some of the treated mice, it is unlikely that these conditions would be reproduced in a clinical setting should patients undergoing FVIII gene therapy for hemophilia A require infusions of FVIII to supplement the transgenic FVIII provided by gene delivery. On the other hand, one could envisage a scenario in which hemophilia A patients who would be candidates for gene therapy would have already developed inhibitors in their plasma. Thus, an important extension of this work will be to evaluate the effectiveness of HSC-directed sfVIIIΔB gene therapy-mediated tolerance induction and long-term correction of hemophila A under nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens in mice with preexisting FVIII inhibitors, and the extent to which immunosuppressive adjunct therapies would be beneficial in this context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

FVIII-Deficient Knockout Mice

E16 hemophilia A male or female FVIII (exon 16) knockout mice on a C57BL/6 background were used as bone marrow transplant donors and recipients [18]. Colonies of the E16 mice were maintained by breeding hemizygous affected males and homozygous affected females. These mice exhibit FVIII activity of <1% of normal plasma levels by analysis with the COATEST assay as previously described [6]. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Production of Vector Conditioned Medium

The oncoretroviral vector used in all experiments was MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP and vector conditioned medium was prepared by transient transfection of the Phoenix-Eco packaging cell line as previously described [6]. Vector titers were 1−1.2 × 106 transducing units/ml.

Bone Marrow Cell Transduction and Transplantation

Bone marrow was collected from 6- to 9-week-old E16 mice and transduced for 3 consecutive days (4 h each day) by incubation with MSGV-sfVIIIΔB-IRES-EGFP vector conditioned medium and 8 μg/ml polybrene as previously described [6]. Recipient mice were divided into three groups according to the conditioning regimen. In the first group, the mice received a minimally myeloablative conditioning regimen of 550 cGy total body irradiation from a 137Cs source (mice #1-#15). A second group of mice (mice #16-#27) received a myeloablative dose of 800 cGy total body irradiation. In a third group, 4 mice (BU1-BU4) received nonmyeloablative conditioning with busulfan [21]. Busulfan (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) at a concentration of 10 mg/ml, then diluted with deionized distilled water to 2 mg/ml [38]. Mice were injected with 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally on days −3 and −2 (day 0 = day of transplant). The total administered busulfan dose was 20 mg/kg. Irradiated mice received 2 × 106 cells sorted for EGFP expression 48 h after the third transduction. EGFP+ cell sorting was performed on a BD FACSAria instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) essentially as described previously [6]. Busulfan-conditioned mice received either 2 × 107 (mouse BU1) or 1.5 × 107 (mice BU2-BU4) unsorted cells 24 h after the last transduction (transduction efficiency was 56−58%).

Immunophenotyping of Peripheral Blood Cells Expressing EGFP

Peripheral blood was collected from sfVIIIΔB gene-treated and control mice in 1/10 volume of 0.1M Na citrate and then incubated with purified anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Fc Block/clone 2.4G2; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/2% fetal bovine serum (FBS)/0.1% sodium azide for 15 min at 4°C. Immunophenotyping of EGFP+ cells was carried out essentially as described [39] with saturating concentrations of R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies recognizing murine CD19 (clone 1D3), CD90.2 (Thy1.2; clone 53−2.1), CD11b (integrin αM chain, Mac-1 α chain; clone M1/70) and Ly-6G (clone 1A8). Corresponding PE-conjugated rat IgG2a,κ or IgG2b,κ isotype controls were included in each analysis (all antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen).

Southern and Northern Blot Analyses

Southern and Northern blot analyses were carried out as previously described [6]. Digital images were acquired using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager and radioactivity quantitated using ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences Corp.).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis of samples was performed as previously described [6]. Recombinant full-length human FVIII (American Diagnostica, Inc. Stamford, CT, USA) and recombinant human BDD-FVIII (ReFacto®; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) were used as positive controls and MagicMark-XP (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) was electrophoresed in parallel as a molecular weight marker.

Measurement of FVIII Activity

FVIII activity was determined by a chromogenic functional assay (COATEST VIII:C/4; DiaPharma Group, Inc., West Chester, OH, USA) as previously described [6].

FVIII and Tetanus Toxoid Immunizations

At 18 (mouse BU1), 22 (mice BU3 and BU4), 26 (mice #1-#15) and 27 (mice #16-#27) weeks after transplantation, intravenous challenge with human FVIII was initiated. Mice received four intravenous injections of 5 IU plasma/albumin-free recombinant full-length human FVIII (ADVATE, Baxter Healthcare Corp., Westlake Village, CA, USA) in PBS, followed by another four intravenous injections of 10 IU FVIII at weekly intervals. Eleven age-matched naive E16 mice were also immunized in the same manner and served as controls. Peripheral blood samples were obtained before the first, fourth and eighth immunizations for serum and plasma collection to assess total and inhibitory anti-FVIII antibodies, respectively. All mice except two animals selected for subsequent tetanus toxoid immunization were sacrificed 3 days after the final FVIII injection and their bone marrow, spleen and thymus were analyzed for presence of EGFP+ cells. Two of the 800 cGy-irradiated mice (mice #26 and #27) and four naive E16 mice were immunized with tetanus toxoid (List Biological Laboratories, Inc., Campbell, CA, USA) 3 weeks after the final FVIII injection as follows: 4 μg tetanus toxoid was mixed with 1 mg Al (OH)3 adjuvant (Alhydrogel 2%; Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation, Westbury, NY, USA), diluted in sterile saline to a total volume of 108 μl and injected intraperitoneally. Two weeks later, sera from these mice was assessed for the presence of anti-tetanus toxoid antibodies by ELISA (described below).

Detection of FVIII, and Anti-FVIII and Anti-Tetanus Toxoid Antibodies

FVIII antigen in murine plasma was measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions with slight modifications. Briefly, serial dilutions of recombinant human BDD-FVIII (ReFacto®; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.) were made in a cocktail of kit-supplied diluent spiked with hemophilia A plasma and used for generating a standard curve. All plasma samples were quick-thawed at 37°C, diluted (1:5 to 1:20), and their FVIII concentration measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Antibodies against FVIII were measured by coating 96-well high-binding microtiter plates (Fisher Scientific, Agawam, MA, USA) with 250 mU/well (2.5 U/ml) of recombinant full-length plasma/albmin-free human FVIII (ADVATE; Baxter Healthcare Corp.) in 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). After overnight binding at 4°C, wells were washed twice with PBS/0.05% Tween 20 and blocked (2 h, room temperature) with PBS/1% BSA. Following four washes, serum samples (diluted from 1:10 to 1:100,000) and standards were added to wells and allowed to bind for 3 h at room temperature. Plates were then washed four times and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chain specific; SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) (1:2000) was added for 1 h at 37°C. After four more washes, bound horseradish peroxidase activity was detected by adding 400 μg/ml o- phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) plus 0.03% H2O2 in citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5) for 5 min followed by standard acid stop (2.5 M sulfuric acid). Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using an ELISA plate reader (Labsystems Multiskan Plus, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and the antibody concentration was reported as the average of at least two readings within the linear portion of the standard curve. The standard curve was generated by serial dilutions of a monoclonal anti-human FVIII light chain antibody (ESH4, American Diagnostica Inc., Stamford, CT, USA) in PBS/1% BSA/0.05% Tween 20. The sensitivity of this ELISA was ∼7.8 ng/ml.

ELISA for detection of anti-tetanus toxoid antibodies was done exactly as for anti-FVIII antibodies, except that 5 μg/ml tetanus toxoid (List Biological Laboratories, Inc.) was used to coat the dishes overnight and serum samples were diluted 1:3.

Inhibitor antibodies against human FVIII were measured using the standard Bethesda assay [40]. Test murine plasma was heat-inactivated at 55°C for 30 min to eliminate endogenous FVIII and thrombin. Various dilutions of test mouse plasma in 0.1 M imidazole buffer (pH 7.4) were incubated with the same volume of normal pooled human plasma (Calibration plasma; DiaPharma Group, Inc., West Chester, OH, USA) for 2 h at 37°C. A control incubation mixture consisting of a 1:1 dilution of normal pooled plasma and imidazole buffer was included in each series of measurements. After the 2 h incubation, FVIII activity was measured in the control and test mixtures with the functional COATEST assay. The percent residual FVIII activity in the test samples relative to the control mixture was calculated. The inhibitor titer is the reciprocal of the dilution of inhibitor plasma that yields approximately 50% residual FVIII activity in the test system and is expressed in Bethesda units per ml. Bethesda titers were calculated by interpolation from a semi-logarithmic standard curve, using at least two data points falling within a range of 25−75% residual FVIII activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL65519 and HL66305 (to R.G.H.). Portions of this study were performed by M.M. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree in Genetics from the Institute for Biomedical Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolton-Maggs PH, Pasi KJ. Haemophilias A and B. Lancet. 2003;361:1801–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ananyeva NM, et al. Inhibitors in hemophilia A: mechanisms of inhibition, management and perspectives. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2004;15:109–124. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saenko EL, Ananyeva NM, Moayeri M, Ramezani A, Hawley RG. Development of improved factor VIII molecules and new gene transfer approaches for hemophilia A. Curr Gene Ther. 2003;3:27–41. doi: 10.2174/1566523033347417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.High KA. Gene transfer as an approach to treating hemophilia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29:107–120. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawley RG. Progress toward vector design for hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2001;1:1–17. doi: 10.2174/1566523013348904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moayeri M, Ramezani A, Morgan RA, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Sustained phenotypic correction of hemophilia A mice following oncoretroviral-mediated expression of a bioengineered human factor VIII gene in long-term hematopoietic repopulating cells. Mol Ther. 2004;10:892–902. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian J, Collins M, Sharpe AH, Hoyer LW. Prevention and treatment of factor VIII inhibitors in murine hemophilia A. Blood. 2000;95:1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ally BA, et al. Prevention of autoimmune disease by retroviral-mediated gene therapy. J Immunol. 1995;155:5404–5408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sykes M, Sachs DH, Nienhuis AW, Pearson DA, Moulton AD, Bodine DM. Specific prolongation of skin graft survival following retroviral transduction of bone marrow with an allogeneic major histocompatibility complex gene. Transplantation. 1993;55:197–202. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199301000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher IK, et al. Use of gene therapy to suppress the antigen-specific immune responses in mice to an HLA antigen. Transplantation. 1996;62:831–836. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199609270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans GL, Morgan RA. Genetic induction of immune tolerance to human clotting factor VIII in a mouse model for hemophilia A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5734–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bracy JL, Iacomini J. Induction of B-cell tolerance by retroviral gene therapy. Blood. 2000;96:3008–3015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heim DA, et al. Introduction of a xenogeneic gene via hematopoietic stem cells leads to specific tolerance in a rhesus monkey model. Mol Ther. 2000;1:533–544. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson G, et al. Engraftment of retroviral EGFP-transduced bone marrow in mice prevents rejection of EGFP-transgenic skin grafts. Mol Ther. 2003;8:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kung SK, et al. Induction of transgene-specific immunological tolerance in myeloablated nonhuman primates using lentivirally transduced CD34+ progenitor cells. Mol Ther. 2003;8:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman D, Tian C, Iacomini J. Induction of donor-specific tolerance in sublethally irradiated recipients by gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2005;12:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi L, Lawler AM, Antonarakis SE, High KA, Gearhart JD, Kazazian HH., Jr. Targeted disruption of the mouse factor VIII gene produces a model of haemophilia A. Nat Genet. 1995;10:119–121. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qian J, Borovok M, Bi L, Kazazian HH, Jr., Hoyer LW. Inhibitor antibody development and T cell response to human factor VIII in murine hemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H, et al. Mechanism of the immune response to human factor VIII in murine hemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye P, et al. Naked DNA transfer of factor VIII induced transgene-specific, species-independent immune response in hemophilia A mice. Mol Ther. 2004;10:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson G, et al. Nonmyeloablative conditioning is sufficient to allow engraftment of EGFP-expressing bone marrow and subsequent acceptance of EGFP-transgenic skin grafts in mice. Blood. 2003;101:4305–4312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kootstra NA, Matsumura R, Verma IM. Efficient production of human FVIII in hemophilic mice using lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2003;7:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittman DD, Alderman EM, Tomkinson KN, Wang JH, Giles AR, Kaufman RJ. Biochemical, immunological, and in vivo functional characterization of B-domain-deleted factor VIII. Blood. 1993;81:2925–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kustikova O, et al. Clonal dominance of hematopoietic stem cells triggered by retroviral gene marking. Science. 2005;308:1171–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1105063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Zettervall O, Dahlback B. Noncoagulation inhibitory factor VIII antibodies after induction of tolerance to factor VIII in hemophilia A patients. Blood. 1990;75:378–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilles JG, Arnout J, Vermylen J, Saint-Remy JM. Anti-factor VIII antibodies of hemophiliac patients are frequently directed towards nonfunctional determinants and do not exhibit isotypic restriction. Blood. 1993;82:2452–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoeben RC, Einerhand MP, Briet E, van Ormondt H, Valerio D, van der Eb AJ. Toward gene therapy in haemophilia A: retrovirus-mediated transfer of a factor VIII gene into murine haematopoietic progenitor cells. Thromb Haemost. 1992;67:341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aiuti A, et al. Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Science. 2002;296:2410–2413. doi: 10.1126/science.1070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagley J, Bracy JL, Tian C, Kang ES, Iacomini J. Establishing immunological tolerance through the induction of molecular chimerism. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1331–1337. doi: 10.2741/bagley. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brocker T, Riedinger M, Karjalainen K. Targeted expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules demonstrates that dendritic cells can induce negative but not positive selection of thymocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;185:541–550. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Amine M, Melo M, Kang Y, Nguyen H, Qian J, Scott DW. Mechanisms of tolerance induction by a gene-transferred peptide-IgG fusion protein expressed in B lineage cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5631–5636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian C, Bagley J, Iacomini J. Expression of antigen on mature lymphocytes is required to induce T cell tolerance by gene therapy. J Immunol. 2002;169:3771–3776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian C, Bagley J, Forman D, Iacomini J. Induction of central tolerance by mature T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:7217–7222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurts C, et al. CD8 T cell ignorance or tolerance to islet antigens depends on antigen dose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12703–12707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker LS, Abbas AK. The enemy within: keeping self-reactive T cells at bay in the periphery. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:11–19. doi: 10.1038/nri701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathis D, Benoist C. Back to central tolerance. Immunity. 2004;20:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurtz J, Wekerle T, Sykes M. Tolerance in mixed chimerism - a role for regulatory cells? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Askenasy N, Yolcu ES, Shirwan H, Wang Z, Farkas DL. Cardiac allograft acceptance after localized bone marrow transplantation by isolated limb perfusion in nonmyeloablated recipients. Stem Cells. 2003;21:200–207. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-2-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akimov SS, Ramezani A, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Bypass of senescence, immortalization and transformation of human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:93–102. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasper CK, et al. Proceedings: A more uniform measurement of factor VIII inhibitors. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1975;34:612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]