Abstract

A 5-year-old, female llama (Lama glama) developed acute, progressive neurological disease, characterized by recumbency, muscle fasciculations, intermittent convulsions/opisthotonos, and absent menace responses. Postmortem histopathologic lesions, limited to the cerebral cortex, consisted of necrosis of the superficial and deep laminae. The clinical disease and microscopic lesions were consistent with polioencephalomalacia.

Résumé

Polio-encéphalomalacie chez un lama. Une femelle lama (Lama glama) âgée de 5 ans a développé une maladie neurologique aigue et progressive caractérisée par un décubitus, de la fasciculation musculaire, des convulsions/opisthotonos intermittents et l’absence de réponse à la menace. Les lésions histopathologiques postmortem, limitées au cortex cérébral, comprenaient une nécrose des laminae superficielle et profondes. Les signes cliniques et les lésions microscopiques étaient compatibles avec une polio-encéphalomalacie.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

In early August 2006, a 5-year-old, female llama (Lama glama) with an unknown breeding history was found recumbent and unwilling to rise by the owners, leading to concerns about possible dystocia. The llama was kept with a number of other llamas in an earthen pen with no access to pasture. All were fed a grass and timothy hay mix, which was occasionally supplemented with small amounts of oats, and they were given water from a nearby well. No other llamas were affected.

Upon examination, the llama was in sternal recumbancy and unwilling or unable to rise. The head and neck were held stiffly erect, and marked, diffuse muscle fasciculations were present. The neck would intermittently become limp, and the llama would assume an opisthotonos-like position. Menace response was absent bilaterally; however, pupillary light reflexes were intact. The temperature was 39.1°C (normal, 37.5°C to 38.9°C) and the heart rate 84 beats/min (normal; 60 to 90 bpm). The respiratory rate could not be assessed, due to the muscle fasciculations.

The history and neurologic signs were indicative of a fore-brain lesion; initial differential diagnoses included polioencephalomalacia, due to either thiamine deficiency or sulfate toxicity; pregnancy toxemia; lead poisoning; West Nile virus infection; rabies; bacterial encephalitis; hepatic encephalopathy; and head trauma. Blood samples were taken and submitted to Prairie Diagnostic Services in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, for examination (Table 1). The llama was prescribed treatment for polioencephalomalacia: administration of thiamine (Thiamine HCL; Rafter 8, Calgary, Alberta), approximately 8 mg/kg bodyweight (BW), IM, q4h for 4 treatments. However, the llama was found dead before the 3rd treatment.

Table 1.

Results from the clinical pathologic examination

| Result | Reference interval | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrocytes | |||

| Hct | 0.228 | 0.250–0.445 | L/L |

| Reticulocytes | 0.1 | — | % |

| Leukocytes | |||

| WBC | 50.1 | 7.2–22.0 | × 109/L |

| Segmented neutrophils | 44.1 | 2.9–15.0 | × 109/L |

| Band neutrophils | 5.0 | 0.0–0.1 | × 109/L |

| Toxic change | 1+ | — | — |

| Lymphocytes | 0.5 | 1.0–7.6 | × 109/L |

| Plasma total solids | |||

| Total solids | 61 | 47–73 | g/L |

| Fibrinogen | 1 | 1.0–5.8 | g/L |

| Total solids: fibrinogen ratio | 61:1 | — | — |

Hct — hematocrit; WBC — white blood cells

Results from analysis of the blood sample revealed a moderate leukocytosis, characterized by marked neutrophilia, with left shift and toxic change. In addition, there was moderate lymphopenia, and mild nonregenerative anemia (Table 1). These results were interpreted to be indicative of either a chronic inflammatory process or a severe stress response with superimposed anemia. Additionally, there was marked hyperglycemia (glucose, 12.7 mmol/L, normal: 2.8 to 6.0 mmol/L), which might also have been indicative of a stress response. Serum biochemical analysis showed no evidence of liver disease.

The llama was submitted to Prairie Diagnostic Services for necropsy. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample was collected from the atlanto-occipital space for possible future antibody testing. Cytologic analysis of the CSF was also performed; the results were unremarkable. No significant abnormalities were seen on gross examination, but it was noted that the llama was not pregnant and was in fair body condition, with hay and a small amount of whole grain present in the C1 gastric compartment (1st of 3 gastric compartments in camelids). The brain was examined under ultraviolet (UV) light at 365 nm, but no areas of fluorescence characteristic of polioencephalomalacia (PEM) were detected.

Immunohistochemical staining and fluorescent antibody tests for rabies were conducted, the results from both of which were negative. The lead concentration in liver collected at necropsy was within normal limits.

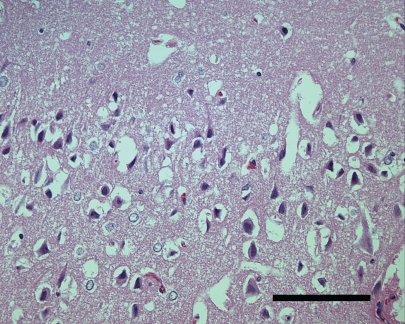

Histopathologic examination of the brain revealed moderate perineuronal vacuolation in the superficial and deep laminae of the cerebrum (Figure 1). In addition, several necrotic, shrunken neurons with eosinophilic cytoplasm were observed, resulting in a final diagnosis of PEM.

Figure 1.

Cerebrum, superficial lamina. Perineuronal vacuolation and numerous shrunken neurons. Hematoxylin and eosin, bar = 100 μm.

Polioencephalomalacia is a common degenerative neurologic disease of ruminants, characterized by laminar necrosis of grey matter in the cerebral cortex (1). Although PEM is rarely reported in camelids, the clinical signs and histopathologic findings in this case were consistent with other published cases in these species (2–4).

Historically, PEM in ruminants is most often attributed to a relative thiamine deficiency (2). Neurologic signs are a caused by cerebrocortical degeneration resulting from energy depletion, as thiamine is a cofactor required for carbohydrate metabolism in the brain (5). Since gastric microbes in ruminants and camelids are able to synthesize thiamine, thiamine deficiency in these species is believed to be due, not to deficient dietary intake but rather to metabolic abnormalities. These may include production of thiaminase enzymes by microbes in the forestomach, the ingestion of plants containing thiaminase, or decreased intestinal absorption or increased fecal excretion of thiamine (5). In this case, since the llama was not allowed access to pasture and had been fed a low carbohydrate and high roughage diet, with no history of recent diet change, a disruption in thiamine metabolism may not be the most likely cause of the PEM. Additionally, treatment with thiamine, 250 to 1000 mg, IM, q4-12h, is usually highly effective in llamas with PEM caused by thiamine deficiency (2). In this case, the lack of response to treatment may indicate an alternative etiology.

More recently, excess intake of dietary sulfur has been associated with PEM in ruminants (1,6). The proposed mechanism involves metabolism of ingested sulfur compounds to hydrogen sulfide gas by ruminal microbes. This toxic gas is either absorbed though the ruminal wall or eructated and inhaled (1). Hydrogen sulfide is thought to affect cytochrome oxidase and inhibit aerobic metabolism in the brain. However, it may also be involved in the formation of free radicals or act as an exogenous neuromodulator (1). In this case, a possible source of excessive dietary sulfur intake could be the drinking water. Cases of sulfur-induced PEM resulting from high water sulfate levels have been reported in beef herds in central Saskatchewan; they are believed to be more prevalent in the summer when increased ambient temperature leads to increased water consumption (1,6). It was suggested to the owners that they have the water tested for sulfate levels; however, the results of this testing were not forwarded to the clinician.

Rumen pH can effect the formation of hydrogen sulfide, with acidic conditions favoring formation of the gas (1). Camelids may be more resistant to sulfur-induced PEM than other species, because effective gastric absorption of volatile fatty acids, along with bicarbonate secretion by mucosal glands in the C1 gastric compartment, results in buffering and the prevention of dramatic fluctuations in gastric pH (3).

Although an unlikely alternative diagnosis in this case, it should be noted that the history, clinical signs, and histological findings are somewhat similar to those in Clostridium perfringens type D enterotoxaemia. This is an invariably fatal disease of young, fattening lambs and, less commonly, goat kids and calves (5). It is usually associated with a sudden diet change leading to intestinal overgrowth of C. perfringens type D (5). Epsilon toxin produced by the bacterium can act on the brain to produce neurological signs, including recumbency, convulsions, opisthotonos, and blindness, and histological lesions of focal symmetrical encephalomalacia (FSE) (7,8). These lesions consist of noninflammatory necrosis of the brain, featuring numerous eosinophillic degenerating neurons (7). The areas of the brain most often affected in FSE include the internal capsule, midbrain, thalamus, and cerebellar peduncles, and the lesions are usually bilaterally symmetrical (7,8). This differs somewhat from PEM, in which degenerative lesions can be asymmetrical and are confined to the cortical grey matter, as seen in this case. Also, since epsilon toxin acts on the vascular endothelium, the lesions of FSE are often preceded by perivascular edema and hemorrhages (8). Additionally, there are frequently other postmortem lesions due to the systemic effect of the toxin, including enterocolitis; pulmonary edema; pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial effusions; and rapid postmortem autolysis of the kidneys, none of which were seen in this case (8).

Since the signalment and postmortem findings in this case were inconsistent with FSE, PEM is the most likely diagnosis. Nevertheless, C. perfringens enterotoxaemia could have been ruled out in this llama by testing the intestinal contents and tissue fluids for epsilon toxin. However, the results would have had to have been interpreted in relation to the entire clinical picture, since toxin testing is neither completely sensitive nor specific for this disease.

Several laboratory findings in this case were inconsistent with the diagnosis of PEM. These included the absence of fluorescence on UV light examination of the brain, as well as the abnormalities seen on the complete blood (cell) count.

Although the leukogram could be interpreted as reflecting a chronic inflammatory process, which would be inconsistent with a diagnosis of PEM, other cases of PEM in llamas have included a similarly abnormal leukogram with superimposed hyperglycemia, suggesting that the observed changes may be stress induced (4). Additionally, although nonregenerative anemia in llamas can be associated with chronic disease, it is not uncommon for this abnormality to be present without a known cause (9).

Fluorescence of cerebral lesions under UV light at 365 nm is often used for rapid diagnosis of PEM. However, it is not uncommon for fluorescence to be absent in early cases of PEM, as may have been the case with this llama (10). This is because the fluorescence results from autofluorescence of ceroid-lipofuscin in lipophages as they engulf necrotic lipid in the brain (10). In early cases of the disease, the lipophages have not yet engulfed sufficient material to be visible under UV light.

This report serves to further illustrate the unusual clinical and laboratory findings of PEM in llamas, as well as possible causes of the disease in this species.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs. Nathalie Tokateloff and Chris Clark for their guidance. CVJ

Footnotes

Reprints will not be available from the author.

Dr. Himsworth will receive 50 free reprints, courtesy of The Canadian Veterinary Journal.

References

- 1.Gould DH. Polioencephalomalacia. J Anim Sci. 1998;76:309–314. doi: 10.2527/1998.761309x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum KH. Neurologic diseases of llamas. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1994;10:383–386. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck C, Dart AJ, Collins MB, Hodgson DR, Parbery J. Polioencephalomalacia in two alpacas. Aust Vet J. 1996;74:350–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1996.tb15442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiupel M, VanAlstine W, Chilcoat C. Gross and microscopic lesions of polioencephalomalacia in a llama (Llama glama) J Zoo Wildl Med. 2003;34:309–313. doi: 10.1638/01-081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGavin MD, William WC, James FZ. Thomson’s Special Veterinary Pathology. 3. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001. pp. 410–412. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haydock D. Sulfur-induced polioencephalomalacia in a herd of rotationally grazed beef cattle. Can Vet J. 2003;44:828–829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartley WJ. A focal symmetrical encephalomalacia of lambs. NZ Vet J. 1956;4:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buxton D, Morgan KT. Studies of lesions produced in the brains of colostrum deprived lambs by Clostridium welcii (Cl. perfringens) type D toxin. J Comp Pathol. 1976;86:435–447. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(76)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garry F, Weiser G, Belknap E. Clinical pathology of llamas. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1994;10:201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little PB. Identity of fluorescence in polioencephalomalacia. Vet Rec. 1978;103:76. doi: 10.1136/vr.103.4.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]