Abstract

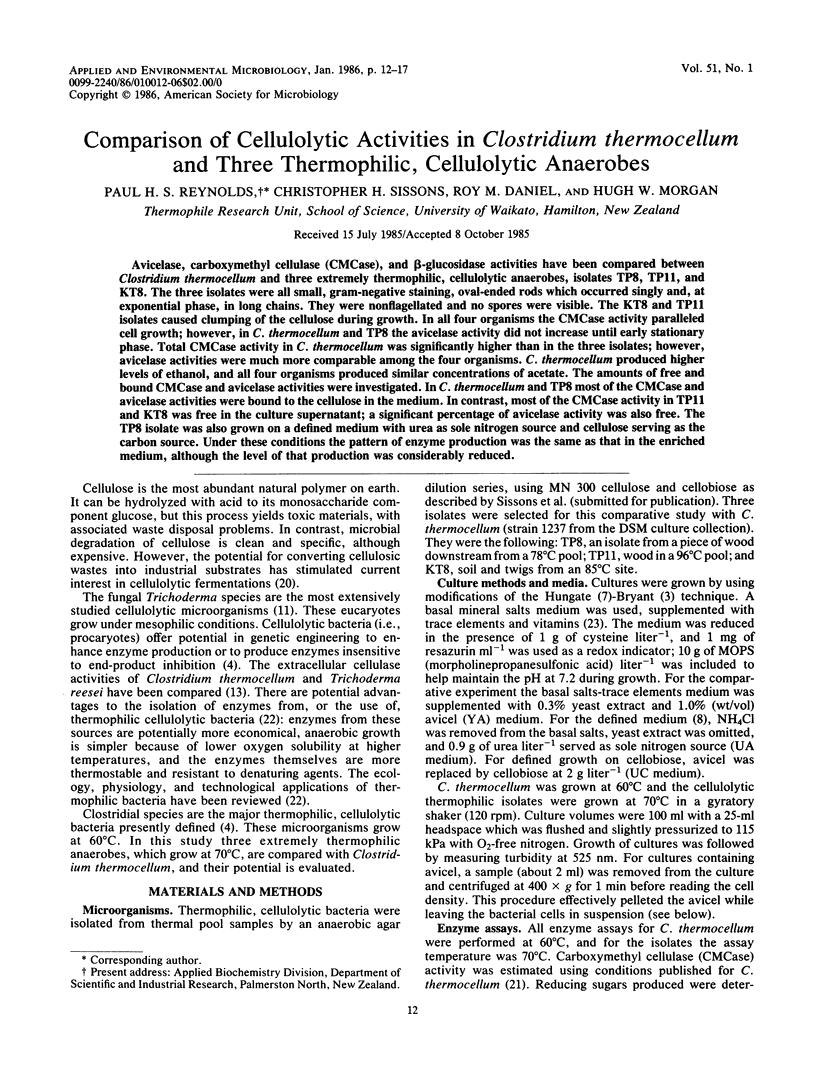

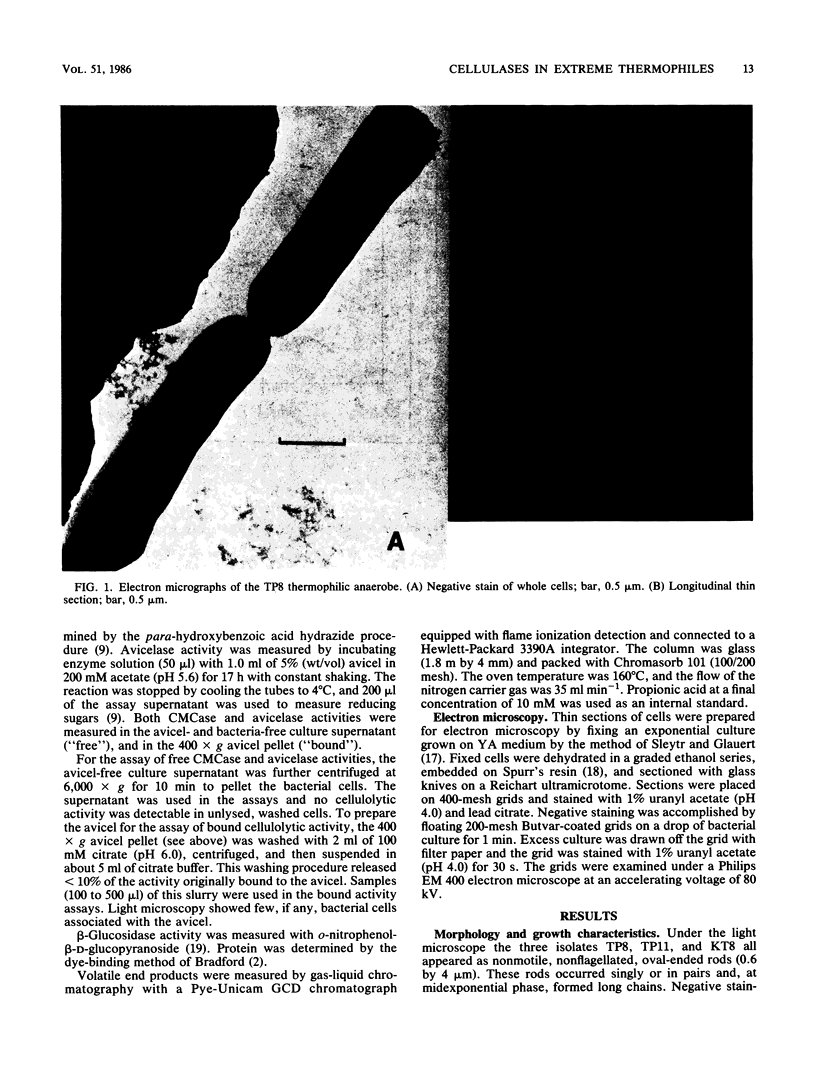

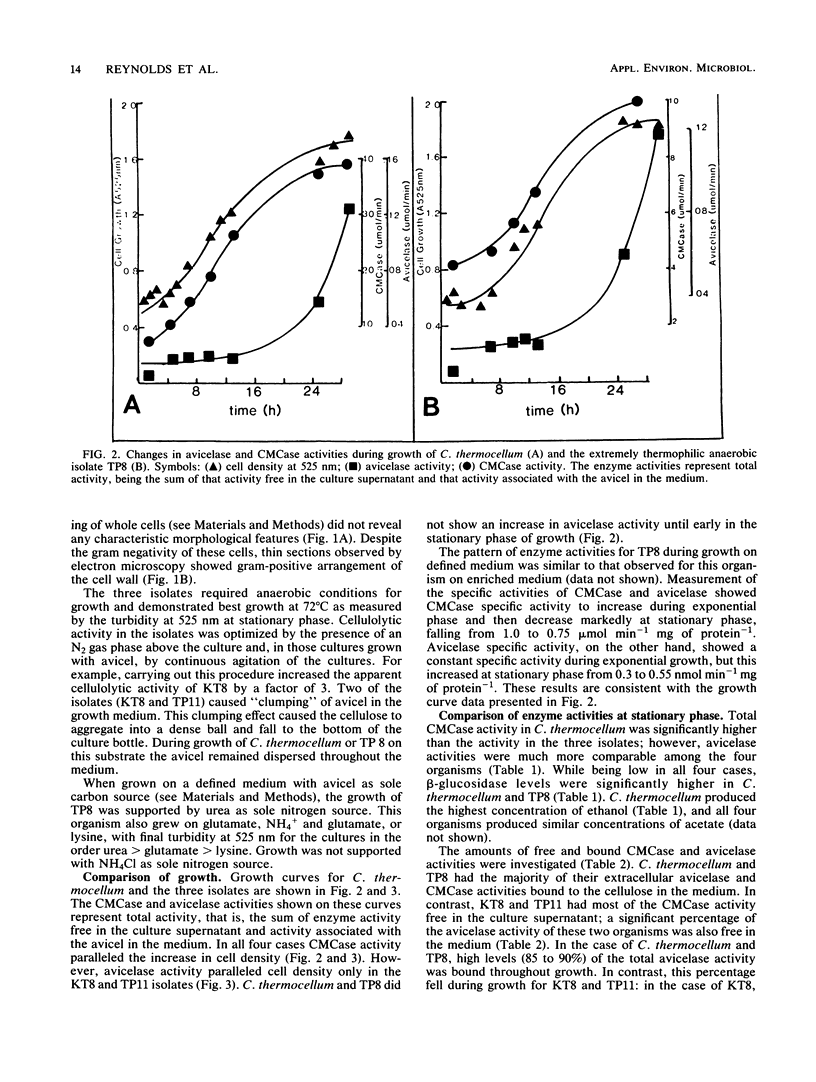

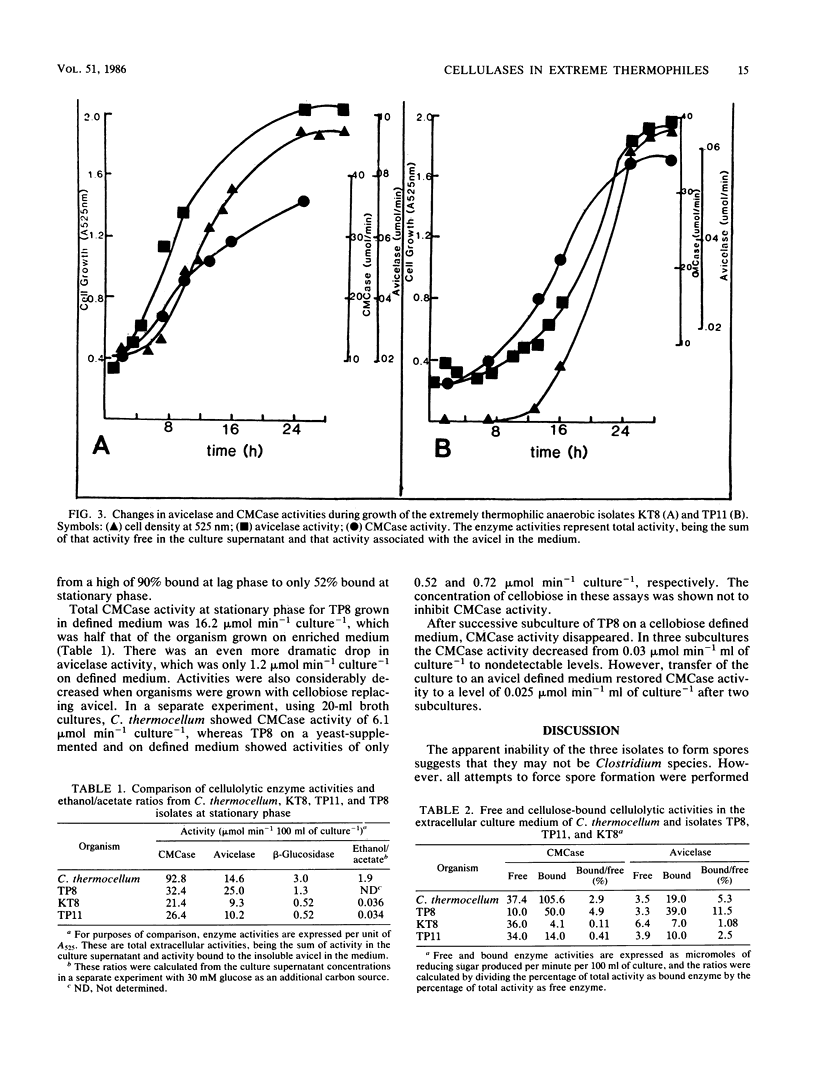

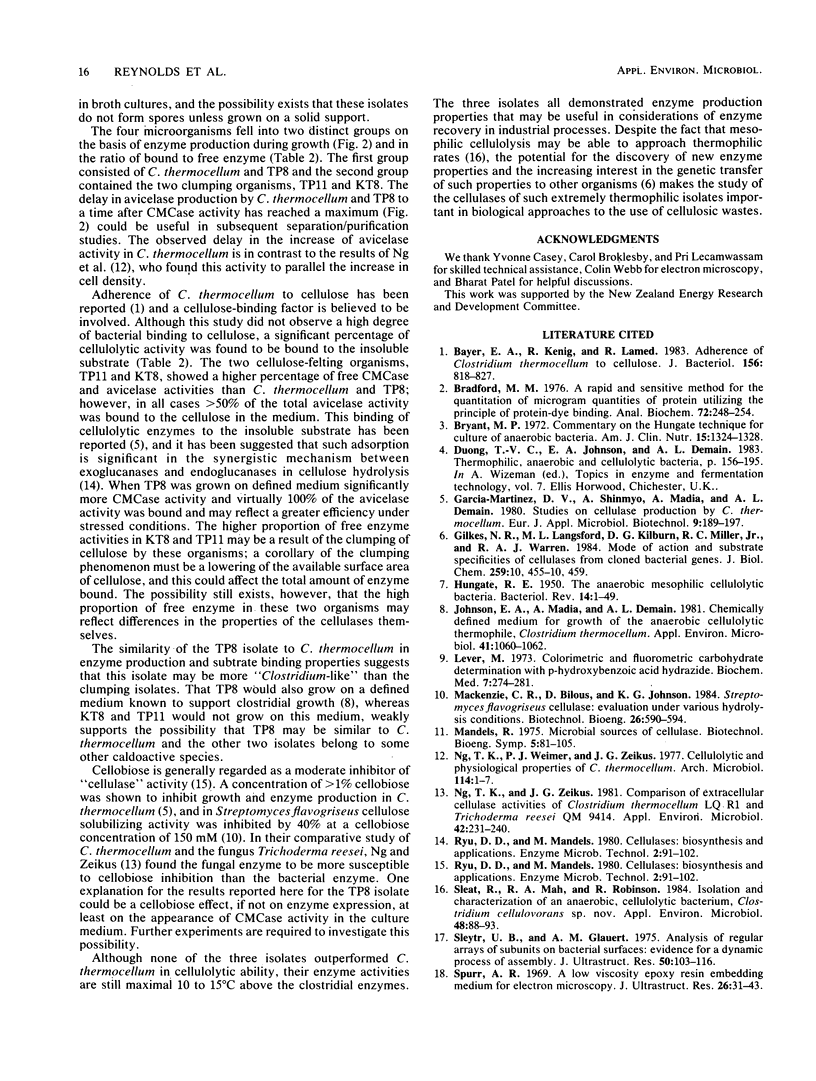

Avicelase, carboxymethyl cellulase (CMCase), and β-glucosidase activities have been compared between Clostridium thermocellum and three extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic anaerobes, isolates TP8, TP11, and KT8. The three isolates were all small, gram-negative staining, oval-ended rods which occurred singly and, at exponential phase, in long chains. They were nonflagellated and no spores were visible. The KT8 and TP11 isolates caused clumping of the cellulose during growth. In all four organisms the CMCase activity paralleled cell growth; however, in C. thermocellum and TP8 the avicelase activity did not increase until early stationary phase. Total CMCase activity in C. thermocellum was significantly higher than in the three isolates; however, avicelase activities were much more comparable among the four organisms. C. thermocellum produced higher levels of ethanol, and all four organisms produced similar concentrations of acetate. The amounts of free and bound CMCase and avicelase activities were investigated. In C. thermocellum and TP8 most of the CMCase and avicelase activities were bound to the cellulose in the medium. In contrast, most of the CMCase activity in TP11 and KT8 was free in the culture supernatant; a significant percentage of avicelase activity was also free. The TP8 isolate was also grown on a defined medium with urea as sole nitrogen source and cellulose serving as the carbon source. Under these conditions the pattern of enzyme production was the same as that in the enriched medium, although the level of that production was considerably reduced.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bayer E. A., Kenig R., Lamed R. Adherence of Clostridium thermocellum to cellulose. J Bacteriol. 1983 Nov;156(2):818–827. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.818-827.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant M. P. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972 Dec;25(12):1324–1328. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaubert A. M., Sleytr U. B. Analysis of regular arrays of subunits on bacterial surfaces: evidence for a dynamic process of assembly. J Ultrastruct Res. 1975 Jan;50(1):103–116. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(75)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNGATE R. E. The anaerobic mesophilic cellulolytic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1950 Mar;14(1):1–49. doi: 10.1128/br.14.1.1-49.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. A., Madia A., Demain A. L. Chemically Defined Minimal Medium for Growth of the Anaerobic Cellulolytic Thermophile Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Apr;41(4):1060–1062. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.4.1060-1062.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever M. Colorimetric and fluorometric carbohydrate determination with p-hydroxybenzoic acid hydrazide. Biochem Med. 1973 Apr;7(2):274–281. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(73)90083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandels M. Microbial sources of cellulase. Biotechnol Bioeng Symp. 1975;(5):81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. K., Weimer T. K., Zeikus J. G. Cellulolytic and physiological properties of Clostridium thermocellum. Arch Microbiol. 1977 Jul 26;114(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00429622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. K., Zeikus J. G. Comparison of Extracellular Cellulase Activities of Clostridium thermocellum LQRI and Trichoderma reesei QM9414. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Aug;42(2):231–240. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.2.231-240.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleat R., Mah R. A., Robinson R. Isolation and Characterization of an Anaerobic, Cellulolytic Bacterium, Clostridium cellulovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Jul;48(1):88–93. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.88-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurr A. R. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969 Jan;26(1):31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C. C., Cole A. L., Shepherd M. G. Purification and properties of the cellulases from the thermophilic fungus Thermoascus aurantiacus. Biochem J. 1980 Oct 1;191(1):83–94. doi: 10.1042/bj1910083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer P. J., Zeikus J. G. Fermentation of cellulose and cellobiose by Clostridium thermocellum in the absence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977 Feb;33(2):289–297. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.2.289-297.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]