Abstract

Introduction

Interactions of three copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) PET radiopharmaceuticals with human serum albumin, and the serum albumins of four additional mammalian species, were evaluated.

Methods

64Cu-labeled diacetyl bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazonato)copper(II) (Cu-ATSM), pyruvaldehyde bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazonato)copper(II) (Cu-PTSM), and ethylglyoxal bis(thiosemicarbazonato)copper(II) (Cu-ETS) were synthesized and their binding to human, canine, rat, baboon, and porcine serum albumins quantified by ultrafiltration. Protein binding was also measured for each tracer in human, porcine, rat, and mouse serum.

Results

The interaction of these neutral, lipophilic copper chelates with serum albumin is highly compound- and species-dependent. Cu-PTSM and Cu-ATSM exhibit particularly high affinity for human serum albumin (HSA), while the albumin binding of Cu-ETS is relatively insensitive to species. At HSA concentrations of 40 mg/mL, “% Free” (non-albumin-bound) levels of radiopharmaceutical were 4.0 ± 0.1%; 5.3 ± 0.2%; and 38.6 ± 0.8% for Cu-PTSM; Cu-ATSM; and Cu-ETS, respectively.

Conclusions

Species-dependent variations in radiopharmaceutical binding to serum albumin may need to be considered when using animal models to predict the distribution and kinetics of these compounds in humans.

Keywords: Copper-64, Cu-PTSM, Cu-ETS, Cu-ATSM, serum albumin binding

Introduction

The binding of drug substances to plasma proteins, in part, directs their biodistribution and pharmacokinetics. Protein-bound drug is unable to freely partition across capillary membranes into tissues, making the extent of protein binding a parameter that can alter the distribution and pharmacokinetics of both diagnostic and therapeutic drugs [1, 2]. Human plasma contains approximately 40 different proteins in various concentrations; however, human serum albumin (HSA) is responsible for the majority of known drug-protein binding interactions in blood [3]. Serum albumin is the most abundant plasma protein, present in adult humans at approximately 46 mg/mL and comprising ∼60% of the total serum protein (75 mg/mL) [4]. Structurally, HSA (MW 66,438 kD) has a flexible three domain structure and reversibly binds a large number of diverse exogenous ligands with very high capacity, while also possessing at least two binding sites known to exhibit high affinity for a number of discrete small molecule drugs [5-7].

Drug binding affinity to non-human serum albumins is variable and not predictable based on drug affinities for HSA [8-10]. Examples where the binding to non-human albumin is dramatically different than observed with HSA can be particularly important in pharmaceutical research and development, since such differences may impact translation of pharmacokinetics findings between animal models and humans.

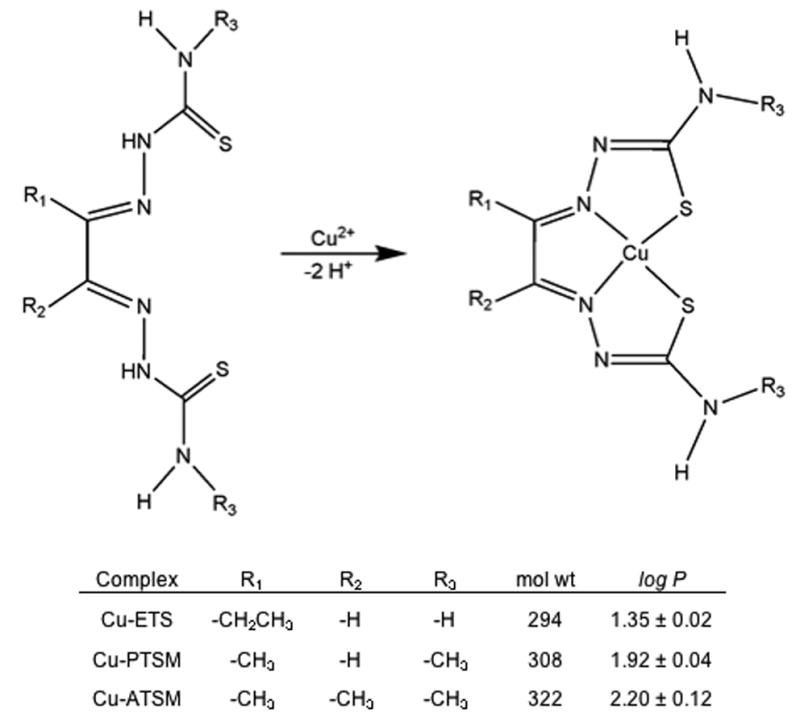

The copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes evaluated in this study, Cu-PTSM, Cu-ETS, and Cu-ATSM (Fig. 1), have shown promise as PET radiopharmaceuticals for imaging tissue perfusion (Cu-PTSM, Cu-ETS) [11-25] and hypoxia (Cu-ATSM) [26-32]. The clinical utility of Cu-PTSM for quantifying perfusion in high-flow tissues, such as hyperemic myocardium, appears limited by the high affinity of this chelate for HSA, a result not predicted by the promising results from canine models [13]. The present study quantifies the protein binding of these three structurally related copper(II) complexes, and demonstrates the potentially highly compound-dependent and species-dependent nature of drug-albumin interactions.

Figure 1.

Synthesis, chemical structure, and selected properties of the copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes. The log P values, characterizing lipophilicity by the tracer's octanol/water partition coefficient (P), were available from the literature [34] or measured as described therein.

Materials and Methods

[64Cu]Cu-Bis(thiosemicarbazone) Synthesis

No-carrier-added 64Cu was obtained as 64Cu2+ in aqueous HCl from the Radionuclide Resource for Cancer Applications at the Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis, MO) and was used within 1 day of receipt. The specific activity of the 64Cu fell in the range of 8-171 mCi/μg (0.3-6.3 GBq/μg) on the day of receipt as reported by the supplier. No-carrier-added 67Cu (1.6 mCi; 59.2 MBq) was obtained as 67Cu2+ in 0.1N HCl (0.05 mL) at a 36 ppm concentration of trace metals (Cu, Pb, Fe, Ni, Ag, Zn) from Trace Radiochemicals, Inc. (Denton, TX). The bis(thiosemicarbazone) ligands, H2PTSM, H2ATSM, and H2ETS, were prepared as described previously [33].

To prepare each 64Cu-radiopharmaceutical, approximately 0.008 g (∼0.03 mmol) of the bis(thiosemicarbazone) ligand was dissolved with heating in 100 μL 50% DMSO: 50% EtOH. In a typical preparation, the ionic 64Cu (350 MBq in 0.012 mL ∼0.1 N HCl) was buffered by the addition of 0.05 mL 0.25N acetate buffer, pH 5.5. The ligand solution (100 μL) was then added to the resulting [64Cu]copper acetate and the mixture allowed to stand for 10 minutes at room temperature. The [64Cu]copper-bis(thiosemicarbazone) solutions were then diluted to <5% EtOH with water and loaded onto a C18 SepPak Light® (Waters, Milford, MA) solid-phase extraction cartridge (previously conditioned with 5mL EtOH, followed by 10mL water). The cartridge was then washed with 10 mL water, followed by elution with ethanol in 0.1 mL fractions to recover the [64Cu]Cu-bis(thiosemicarbazone) chelate. The radiochemical purity of each product was determined by thin layer chromatography using silica gel plates and 100% EtOH as the mobile phase and always exceeded 99% (Rf values of 0.86, 0.84, 0.87, and 0 for [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ETS, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and ionic [64Cu]copper(II) acetate, respectively). Radiochemical yields were typically ∼90% in the combined ethanol fractions for these three compounds, with 60-70% of the radioactivity appearing in the most concentrated of the 0.1 mL fractions. (The “lost radioactivity” remained in the reaction vial or bound to the SepPak cartridge.) Octanol/water partition coefficients (Fig. 1) were available from the literature or measured as described previously [34]. The [67Cu]Cu-PTSM, [67Cu]Cu-ETS and [67Cu]Cu-ATSM tracers were prepared, purified, and analyzed in a similar fashion using reaction mixtures containing ∼200 μCi (7.4 MBq) 67Cu and ∼500 μg ligand.

Ultrafiltration Binding Assays

Human, canine, porcine, baboon, and rat serum albumins were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) as lyophilized powders and reconstituted in 0.9% normal saline at 40 mg/mL. The canine and baboon serum albumins were fraction V powders, while human, porcine, and rat serum albumins were essentially globulin free and at least 99.5% fatty acid free. Frozen sera were purchased from Sigma and used with no additional dilution. Total protein concentrations, as reported in the vendor certificates of analysis for human, rat, porcine, and mouse serums, were 55, 68, 73, and 67 mg/mL, respectively. For the specific lot of porcine serum used, the albumin concentration was reported by the vendor as 30 mg/mL. Amicon Centrifree® (Millipore, Bedford, MA) ultrafiltration devices with 30,000-Dalton NMWL methylcellulose micropartition membranes were used to separate free fractions of each chelate from the protein-bound fractions. Typically, 4 μL aliquots of each radiotracer solution were added to 1 mL of the albumin solution and mixed. Then, 300 μL aliquots of each solution were loaded into the ultrafiltration devices and immediately centrifuged, within 5 minutes of mixing, in a fixed angle rotor for 10 minutes at 2000 × G using a Sorvall RCB-2 centrifuge maintained at 20°C.

As a control, each radiopharmaceutical was similarly added to protein-free saline and aliquots of that solution similarly subjected to the ultrafiltration process. To quantify the extent of radiotracer binding to serum proteins or serum albumin, equal volume samples (generally 30 μL) of the unfiltered load solution and the ultrafiltrate were counted in a Packard Autogamma 5530 automatic gamma counter. For each solution, the “free” (unbound) fraction of radiotracer was then calculated as:

| Eq. 1 |

In the case of the saline control, this calculation provides a measure of the extent to which the radiotracer non-specifically associates with the membrane of the ultrafiltration device. Since the extent of protein binding is implicitly zero in the protein-free saline control solutions, for each radiotracer the protein binding results were normalized to correct for tracer adsorption to the ultrafiltration membrane by the calculation:

| Eq. 2 |

The chemical stability of [67Cu]Cu-PTSM, [67Cu]Cu-ETS and [67Cu]Cu-ATSM in albumin solutions was verified by radioTLC at 1 min, 30 min, and 24 hours after mixing of each 67Cu radiotracer (2 μCi; 0.07 MBq in 5.0 μL 100% EtOH) with HSA (0.1 mL at 40 mg/mL).

Statistical Analysis

The mean free fraction and estimated variance of each compound in saline and protein solution is given by Equations 3 and 4.

| Eq. 3 |

| Eq. 4 |

The mean corrected free fraction for each compound was calculated by the ratio of mean protein free fraction values to mean saline free fraction values (Eq. 5).

| Eq. 5 |

The variance of these compound ratios was estimated with the Delta method, a one-step Taylor approximation for random variables [35] (Eq. 6).

| Eq. 6 |

The standard deviation for the resulting values of “corrected free fractions” is then defined as the square root of the corresponding variance.

A Tukey studentized range test with α = 0.05 was applied using an ANOVA model generated by SAS software version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to compare the mean values of albumin binding for each radiotracer [36].

Results

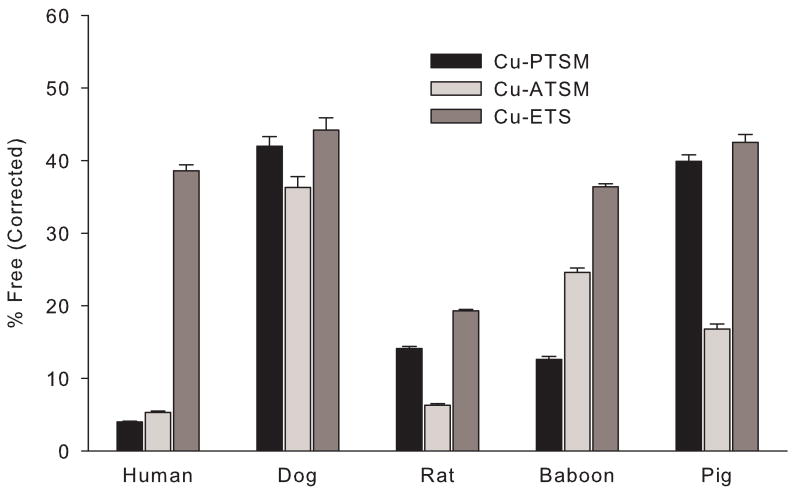

These studies show there can be substantial, species-dependent, variations in the level of copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) radiopharmaceutical binding to serum albumin (Table 1 and Fig. 2), consistent with more limited earlier investigations documenting the variations in binding of Cu-PTSM to human and canine sera and serum albumins [37,38]. The species-dependent variations are most pronounced for Cu-PTSM and Cu-ATSM (Fig. 2), while for each of the serum albumins tested, Cu-ETS exhibited the least protein binding (highest percent free values) and much less species-dependence. However, even for Cu-ETS there is evidence of subtle species-dependent variations in the strength of tracer binding to serum albumin (Fig. 2). The reported protein binding results reflect the reversible association of intact Cu-bis(thiosemicarbazone) chelates with serum albumin, not radiocopper loss to the protein by ligand exchange, since even at 24 hours after mixing of [67Cu]Cu-PTSM, [67Cu]Cu-ETS, and [67Cu]Cu-ATSM with HSA, radioTLC shows only the presence of the intact copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) radiopharmaceuticals.

Table 1.

Binding of 64Cu-Bis(thiosemicarbazone) Complexes to the Serum Albumins and Sera of Various Species

| % Freea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | Species | Serum Albuminb | n | Serum | n |

| Cu-PTSM | Human | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 8 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 5 |

| Rat | 14.1 ± 0.3 | 6 | 14.7 ± 1.2 | 6 | |

| Pig | 39.9 ± 0.9 | 3 | 26.3 ± 1.2 | 6 | |

| Dog | 42.0 ± 1.3 | 4 | - | - | |

| Baboon | 12.6 ± 0.4 | 4 | - | - | |

| Mouse | - | - | 14.6 ± 0.6 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| Cu-ATSM | Human | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 6 | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 5 |

| Rat | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 6 | |

| Pig | 16.8 ± 0.7 | 7 | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 6 | |

| Dog | 36.3 ± 1.5 | 6 | - | - | |

| Baboon | 24.6 ± 0.6 | 4 | - | - | |

| Mouse | - | - | 6.9 ± 0.2 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| Cu-ETS | Human | 38.6 ± 0.8 | 8 | 34.4 ± 2.3 | 4 |

| Rat | 19.3 ± 0.2 | 3 | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 4 | |

| Pig | 42.5 ± 1.1 | 5 | 28.7 ± 1.0 | 6 | |

| Dog | 44.2 ± 1.7 | 4 | - | - | |

| Baboon | 36.4 ± 0.4 | 3 | - | - | |

| Mouse | - | - | 14.9 ± 1.0 | 5 | |

Corrected for non-specific radiotracer association with the ultrafiltration membrane using control data obtained by ultrafiltration of protein-free saline solutions of each chelate, as shown in eq. 2. These saline controls produced values of 0.635 ± 0.039 (n=12), 0.653 ± 0.037 (n=9), and 0.706 ± 0.025 (n=10) as the apparent unbound fractions for Cu-PTSM, Cu-ATSM, and Cu-ETS, respectively, reflecting partial adsorption of the free (non-protein-bound) radiopharmaceuticals to the ultrafiltration membrane.

Serum Albumin concentration of 40 mg/mL.

Figure 2.

Binding of 64Cu-bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes to the serum albumins of various species. Standard deviations were calculated from the variance using the Delta method. Data for each Cu-bis(thiosemicarbazone) complex has been corrected to account for nonspecific tracer binding to the ultrafiltration membrane. In all cases the serum albumin was present at a concentration of 40 mg/mL.

Human serum albumin provides the most dramatic examples of variations in protein-binding among these three structurally similar Cu(II)-bis(thiosemicarbazone) tracers. Approximately 95% of the available [64Cu]Cu-PTSM and [64Cu]Cu-ATSM is bound to HSA, values substantially greater than the observed binding of [64Cu]Cu-ETS to HSA (approximately 60% bound or 40% free) (Table 1). In contrast, canine serum albumin binding of [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS is more uniform (∼42%, 36%, and 44% free, respectively) and dramatically less than the [64Cu]Cu-PTSM and [64Cu]Cu-ATSM binding observed with HSA.

Using multiple Tukey tests with α = 0.05 to compare the mean (uncorrected) free fractions for each radiotracer in albumin solutions, the binding of [64Cu]Cu-PTSM to rat and baboon serum albumins is statistically indistinguishable. In addition, the canine and porcine albumin binding values are similar to each other, but well below the high binding observed with HSA. For [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, values for binding to rat and human serum albumin are not significantly different, but the measured species-to-species differences in binding to canine, porcine, and baboon albumin are statistically significant. Finally, there is not a statistically significant difference between the binding of [64Cu]Cu-ETS to canine and porcine serum albumins, nor is there a statistically significant difference between the [64Cu]Cu-ETS values measured for human and baboon albumin. While more subtle than the species-to-species variations seen with [64Cu]Cu-PTSM and [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, the observed variations in [64Cu]Cu-ETS binding are statistically significant when comparing the canine/porcine albumins to the human/baboon albumins or to rat albumin.

Binding assays were also performed using samples of human, porcine, rat, and mouse sera for comparison to the results obtained for the purified albumins (Table 1). Even though serum albumin is the most abundant plasma protein, binding to additional plasma proteins can be significant [2]. If these radiotracers appreciably bind to additional plasma proteins, such as α1-acid-glycoproteins or globulins, we would expect the extent of binding to be greater for the serum samples than the pure serum albumins.

The serum protein binding of [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS shows the same general trends observed for binding to albumin (Table 1). In human serum, the protein binding of all three radiopharmaceuticals appears nearly identical to the observed binding to HSA; in HSA solutions the levels of unbound tracer were 4.0 ± 0.1%, 5.3 ± 0.2%, and 38.6 ± 0.8% for [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS, respectively, while the corresponding levels of unbound tracer were 4.3 ± 0.2%, 6.2 ± 0.4%, and 34.4 ± 2.3% when tested with human serum. Rat serum and rat serum albumin also provided similar results for both [64Cu]Cu-PTSM and [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, while rat serum showed somewhat higher affinity for [64Cu]Cu-ETS than albumin alone.

The binding of [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS was also assessed in mouse serum, due to the importance of the mouse as an animal model in biomedical research. For all three chelates, the protein binding in mouse serum was similar to that observed in rat serum (Table 1).

In the case of porcine serum vs. serum albumin, for all three radiopharmaceuticals the free fraction of tracer in serum was only ∼65% of the free fraction observed in albumin solution, suggesting an additional porcine serum protein has a significant, but non-discriminate, affinity for binding these agents. To further probe this finding, we directly measured binding to porcine serum albumin at 30 mg/mL, the labeled albumin concentration of the commercial porcine serum (containing 73 mg/mL total protein), as well as the binding to Porcine Immunoglobulin G (PIgG) alone. PIgG is second only to albumin in its serum concentration (20 mg/mL in adult pigs) [39].

The levels of unbound or “free” [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS in 30 mg/mL porcine serum albumin solutions (n = 3, each sample) were 40.8 ± 0.8%, 20.4 ± 0.4%, and 52.4 ± 0.8%, respectively, values similar to, or slightly higher than, the level of free tracer measured at 40 mg/mL (Table 1). At 30 mg/mL porcine albumin, the levels of unbound tracer were significantly higher than the % free values measured in porcine serum (26.3 ± 1.2%, 11.2 ± 0.3%, and 28.7 ± 1.0% for [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS, respectively, Table 1). In PIgG solutions (20 mg/mL), the unbound tracer values for [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, and [64Cu]Cu-ETS were found to be 63.3 ± 2.6%, 64.6 ± 1.4%, and 68.5 ± 3.0%, respectively (n = 4). Thus, PIgG does significantly, but non-discriminately, bind these agents, and would appear to largely account for the observed binding differences between solutions of porcine serum albumin and porcine serum.

Discussion

The diagnostic utility of the PET radiopharmaceuticals tested in this study depends on their ability to freely partition from blood into the extravascular space. The extent to which these copper bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes bind to serum proteins is important, since protein binding may directly limit the rate, and extent, of radiopharmaceutical diffusion from blood into the tissues of interest for imaging. Characterization of the magnitude of protein binding becomes especially important when plasma protein binding is found to vary between species, since such interspecies variation may impact the reliability of animal models in predicting radiopharmaceutical performance in humans. We have previously reported that copper bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes can exhibit significant, species-dependent, binding to serum albumin [37], but those studies did not include evaluation of Cu-ATSM nor the broad range of species examined in the present experiments.

These radiopharmaceutical interactions with serum albumin are reversible, with radioTLC showing no evidence for chemical decomposition of the chelates, consistent with earlier findings [25,37]. Nevertheless, such albumin binding can be detrimental to drug delivery, particularly in applications requiring high first-pass tissue extraction of the pharmaceutical from blood, as is the case with radiotracer methods for probing regional tissue perfusion. The importance of albumin binding is illustrated by the performance of 62Cu-PTSM as a tracer of myocardial perfusion; while this radiopharmaceutical can be used to quantify myocardial blood flow in animals [11-15], and humans at rest [16-17], its highly species-specific association with human serum albumin appears to limit delivery under the high-flow conditions encountered in hyperemic human myocardium [17-21]. In this regard, the dramatically lower, and largely species-independent, binding of Cu-ETS to serum albumin [37] is expected to make Cu-ETS a more robust agent for evaluation of perfusion regardless of species. Cu-ETS remains under investigation as a tracer of myocardial and renal perfusion [22-25].

Like Cu-PTSM and Cu-ETS, the structurally related Cu-ATSM chelate can be reductively decomposed to intracellularly liberate (and trap) the copper radiolabel [25,33,40-43]. However, for Cu-ATSM this redox trapping is sensitive to the level of cell oxygenation, occurring most rapidly in hypoxic cells, leading to investigation of [60,64Cu[Cu-ATSM as a marker of tissue hypoxia [26-31].

Compared to perfusion imaging, which demands high first-pass tissue extraction of the radiopharmaceutical, the impact of strong albumin binding will perhaps be more subtle in the case of Cu-ATSM for assessment of hypoxia. Since hypoxia will tend to be associated with low rates of tissue perfusion, tracer binding to serum albumin may be less influential on target tissue accumulation of the tracer. In fact, if the albumin binding of Cu-ATSM reduces tracer uptake in high-flow normoxic tissue, the plasma protein binding might directly improve hypoxic/normoxic tissue contrast. Nevertheless, the present results clearly indicate that [64Cu]Cu-ATSM, like [64Cu]Cu-PTSM, exhibits significant species-to-species variations in the magnitude of its association with serum albumin, with these tracers sharing the tendency to very strongly associate with human serum albumin. The variations in radiopharmaceutical binding to serum albumin may need to be considered in translation of models of Cu-ATSM distribution and kinetics between species.

Conclusions

The binding of Cu-PTSM, Cu-ETS, and Cu-ATSM to serum proteins is dominated by the interaction of these neutral lipophilic chelates with serum albumin. The association with serum albumin varies considerably between species, particularly for Cu-PTSM and Cu-ATSM, and may need to be considered when translating animal results with these agents to humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from the Purdue Research Foundation, and R01-CA092403. The production of Cu-64 at Washington University School of Medicine is supported by the NCI grant R24 CA86307.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Winters ME. Basic Clinical Pharmacokinetics. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Willkins; 1994. pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertucci C, Domenici E. Reversible and covalent binding of drugs to human serum albumin: methodological approaches and physiological relevance. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:1463–1481. doi: 10.2174/0929867023369673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters T. All About Albumin. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc; 1996. pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenter C, editor. Geigy Scientific Tables. CIBA-GEIGY. 1984. pp. 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter DC, Ho JX. Advances in Protein Chemistry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. Structure of Serum Albumin; pp. 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghuman J, Zunszain PA, Petitpas I, Bhattacharya AA, Otagiri M, Curry S. Structural basis of the drug-binding specificity of human serum albumin. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudlow G, Birkett DJ, Wade DN. The characterization of two specific drug binding sites on human serum albumin. Mol Pharmacol. 1975;11:824–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panjehshahin MR, Yates MS, Bowmer CJ. A comparison of drug binding sites on mammalian albumins. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44(5):873–879. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson A, Karp W, Broderson R. Comparison of the binding characteristics of serum albumins from various animal species. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1990;15:106–111. doi: 10.1159/000457629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosa T, Maruyama T, Otagiri M. Species differences of serum albumins: I. Drug binding sites. Pharm Res. 1997;14(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.1023/a:1012138604016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green MA, Klippenstein DL, Tennison JR. Copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes as potential tracers for evaluation of cerebral and myocardial blood flow with PET. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:1549–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shelton ME, Green MA, Mathias CJ, Welch MJ, Bergmann SR. Kinetics of copper-PTSM in isolated hearts: a novel tracer for measuring blood flow with positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med. 1989;30:1843–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelton ME, Green MA, Mathias CJ, Welch MJ, Bergmann SR. Assessment of regional myocardial and renal blood flow using copper-PTSM and positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1990;82:990–997. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.3.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrero P, Markham J, Weinheimer CJ, Anderson CJ, Welch MJ, Green MA. Quantification of regional myocardial perfusion with generator-produced 62Cu-PTSM and positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1993;87:173–183. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green MA, Mathias CJ, Welch MJ, McGuire A, Perry D, Fernandez-Rubio F. [62Cu]-labeled pyruvaldehyde bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazonato) copper(II): synthesis and evaluation as a positron emission tomography tracer for cerebral and myocardial perfusion. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1989–1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrero P, Hartman JJ, Green MA, Anderson CJ, Welch MJ, Markham J. Assessment of regional myocardial perfusion with generator-produced 62Cu-PTSM and PET in human subjects. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1294–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beanlands RS, Muzik O, Mintun MA, Mangner T, Lee K, Petry N. The kinetics of copper-62-PTSM in the normal human heart. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:684–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melon PG, Brihaye C, Degueldre C, Guillaume M, Czichosz R, Rigo P. Myocardial kinetics of K-38 in humans and comparison with Cu-62-PTSM. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1116–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beanlands RS, Muzik O, Hutchins GD, Woulfe ER, Schwaiger M. Heterogeneity of regional nitrogen-13-labeled ammonia tracer distribution in the normal human heart: comparison with rubidium-82 and copper-62-labeled PTSM. J Nucl Cardiol. 1994;1:225–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02940336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallhaus TR, Lacy J, Whang J, Green MA, Nickles RJ, Stone CK. Human biodistribution and dosimetry of the PET perfusion agent copper-62-PTSM. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1958–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallhaus TR, Lacy J, Stewart R, Bianco J, Green MA, Nayak N. Copper-62-pyruvaldehyde bis(N-4-methylthiosemicarbazone) PET imaging in the detection of coronary artery disease in humans. J Nuc Cardiol. 2001;8:67–74. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2001.109929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.http://www.proportionaltech.com/cuets.htm

- 23.Green MA, Mathias CJ, Willis L, Handa R, Miller M, Hutchins G. Evaluation of Cu-ETS as a PET tracer of regional renal perfusion. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 2005;48:S164. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green MA, Mathias CJ, Willis LR, Handa RK, Miller MA, Hutchins GD. Evaluation of 62Cu-ETS as a PET tracer of renal perfusion in a model of acute focal renal Injury. J Nucl Med. 2006;47 1:146P. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MA, Mathias CJ, Willis LR, Handa RK, Lacy JL, Miller MA. Assessment of Cu-ETS as a PET radiopharmaceutical for evaluation of regional renal perfusion. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis JS, Welch MJ. PET imaging of hypoxia. Q J Nucl Med. 2001;45:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis JS, Sharp TL, Laforest R, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Tumor uptake of copper-diacetyl-bis(N-4-methylthiosemicarbazone): Effect of changes in tissue oxygenation. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obata A, Yoshimi E, Waki A, Lewis JS, Oyama N, Welch MJ. Retention mechanism of hypoxia selective nuclear imaging/radiotherapeutic agent Cu-diacetyl-bis(N-4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (Cu-ATSM) in tumor cells. Ann Nucl Med. 2001;15:499–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02988502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis JS, Herrero P, Sharp TL, Engelbach JA, Fujibayashi Y, Laforest R. Delineation of hypoxia in canine myocardium using PET and copper(II)-diacetyl-bis(N-4-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1557–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan H, Schroeder T, Bowsher JE, Hedlund LW, Wong T, Dewhirst MW. Intertumoral differences in hypoxia selectivity of the PET imaging agent Cu-64(II)-diacetyl-bis(N-4-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2006;47:989–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serganova I, Humm J, Ling C, Blasberg R. Tumor hypoxia imaging. [Editorial Material] Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(18):5260–5264. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blower PJ, Castle TC, Cowley AR, Dilworth JR, Donnelly PS, Labisbal E. Structural trends in copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) radiopharmaceuticals. Dalton Trans. 2003;23:4416–4425. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petering HG, Buskirk HH, Underwood GE. The anti-tumor activity of 2-keto-3 ethoxybutyraldehyde bis(thiosemicarbazone) and related compounds. Cancer Res. 1964;24:367–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.John E, Green MA. Structure-activity relationships for metal-labeled blood flow tracers: comparison of ketoaldehyde bis(thiosemicarbazonato)copper(II) derivatives. J Med Chem. 1990;33:1764–1770. doi: 10.1021/jm00168a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casella G, Berger R. Statistical Inference. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury; 2002. pp. 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- 36.SAS, version 9.1.3. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: pp. 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathias CJ, Bergmann SR, Green MA. Species-dependent binding of copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazone) radiopharmaceuticals to serum albumin. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1451–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan H, Antholine WE, Subczynski WK, Green MA. Release of CuPTSM from human serum albumin after addition of fatty acids. J Inorg Biochem. 1996;61:251–259. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(95)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boukhout BA, Van Asten-Noordijk JJL, Stok W. Porcine IgG. Isolation of two IgG-subclasses and anti-IgG class- and subclass-specific antibodies. Mol Immunol. 1986;23:675–683. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minkel DT, Saryan LA, Petering DH. Structure-function correlations in the reaction of bis(thiosemicarbazone) copper(II) complexes with Ehrlich acites tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1978;38:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petering DH. Carcinostatic copper complexes. In: Sigel H, editor. Metal ions in biological systems. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1980. pp. 197–229. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winkelmann DA, Bermke Y, Petering DH. Comparative properties of the antineoplastic agent 3-ethoxy-2-oxobutyraldehyde bis(thiosemicarbazone) copper(II) and related chelates: linear free energy relationships. Bioinorg Chem. 1974;3:261–277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3061(00)80074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baerga ID, Maickel RP, Green MA. Subcellular distribution of tissue radiocopper following intravenous administration of 67Cu-labeled Cu-PTSM. Nucl Med Biol. 1992;19:697–701. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(92)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]