Abstract

The ability to detect, characterize, and manipulate specific biomolecules in complex media is critical for understanding metabolic processes. Particularly important targets are oxygenases (cytochromes P450) involved in drug metabolism and many disease states, including liver and kidney dysfunction, neurological disorders, and cancer. We have found that Ru photosensitizers linked to P450 substrates specifically recognize submicromolar cytochrome P450cam in the presence of other heme proteins. In the P450:Ru-substrate conjugates, energy transfer to the heme dramatically accelerates the Ru-luminescence decay. The crystal structure of a P450cam:Ru-adamantyl complex reveals access to the active center via a channel whose depth (Ru-Fe distance is 21 Å) is virtually the same as that extracted from an analysis of the energy-transfer kinetics. Suitably constructed libraries of sensitizer-linked substrates could be employed to probe the steric and electronic properties of buried active sites.

Developing methods for detecting mammalian P450s and characterizing their structures (1) would facilitate rational drug design (2) and the engineering of catalysts (3, 4). Although more than 100 mammalian microsomal P450 isozymes have been identified, direct information about their structures and physiological function is lacking. Crystal structures are available for only four P450 oxygenases (5), all of which are water-soluble bacterial enzymes; the best characterized of these, cytochrome P450cam, was targeted in our studies. Here, we report that substrates linked to [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (bpy is 2,2′-bipyridine; Scheme S1; ref. 6) can selectively probe the enzyme in complex media.

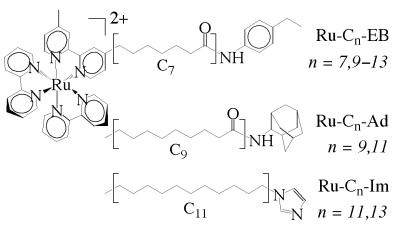

Scheme 1.

Sensitizer-linked substrates (EB, Ad) and ligands (Im)..

The attachment of a sensitizer to substrate, nucleotide, or flavin analogs should improve the ability of such small-molecule probes (7–10) to resolve enzyme active centers while minimizing the need for intensive synthesis, metabolite characterization, and enzyme mutagenesis. Our modular, active-site-directed approach to detection is superior to enzyme- and antibody-based assays: sensitizer-linked substrates assess ligand specificity and enzyme structure and are amenable to combinatorial chemistry. Furthermore, because Ru substrates interact with their targets reversibly, they differ from current probes of heme proteins that rely on covalent modification and chemical analysis (1, 11).

Materials and Methods

P450cam Expression/Crystallization Conditions.

Pseudomonas putida cytochrome P450cam (residues 1–414) containing the mutation Cys334Ala (Quickchange mutagenesis, Stratagene) was overexpressed in Escherichia coli TBY cells from plasmid pUS200 (12) and purified in the presence of camphor with slight modification to procedures previously described (13). P450:Ru-C9-adamantane (Ad) seed crystals of space group P212121 (cell dimensions of 65.4 × 74.5 × 91.7 Å3; one molecule per asymmetric unit; Matthews coefficient (VM) = 2.4; solvent content = 49%) nucleated overnight (4°C; vapor diffusion) from protein separated from camphor and complexed with stoichiometric Ru-C9-Ad. Hanging drops contained an equal volume mixture of reservoir and 430 μM P450:Ru-C9-Ad in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/100 mM KCl/1 mM DTT. The reservoir (final pH ≈6.0) contained 100 mM NaOAc (pH 4.9), 200 mM NH4OAc (pH 7.0), and 9–11% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol (molecular weight 8,000). Diffraction quality crystals (0.15 × 0.15 × 0.5 mm3) were grown over 24–48 h by moving seed crystals into sitting drops of reduced polyethylene glycol concentrations (5–7%).

Structure Determination.

An initial molecular replacement solution (correlation coefficient = 0.53 and Rcryst = Σ∥Fobs| − |Fcalc∥/Σ|Fobs| = 43.4%, for 15.0- to 3.5-Å resolution data) was found by amore (14) with a probe derived from the structure of camphor-bound P450cam (PDB code: 2cpp; ref. 15) by using diffraction data collected from P450:Ru-C9-Ad crystals (1.55-Å resolution; overall Rsym = ΣΣj|Ij − <I>|/ΣΣjIj = 4.8%; overall signal-to-noise ratio = I/σI = 37.4; redundancy = 6.5; 99.2% complete). Diffraction data were collected at 100 K on Beam-line 7-1 (1.08 Å) of the Stanford Synchrotron Research Laboratory and processed with denzo (16). Substantial changes in the regions of P450 distal to the heme were modeled to omit electron density maps with xfit (17). Ru-C9-Ad was positioned into the remaining difference density. The structure was refined by torsion-angle molecular dynamics and positional refinement with cns (18) amidst model rebuilding, water molecule placement, and resolution extension to 1.55 Å. After an overall anisotropic thermal factor correction, bulk-solvent correction, and individual thermal factor refinement, grouped occupancy refinement of Ru-C9-Ad and those residues in multiple conformations produced the final model {4019 scatterers; 1 Ru-C9-Ad as a superposition of the two (Δ and Λ) [Ru(bpy)3]2+ enantiomers; 23 residues in multiple conformations; 427 water molecules; 5 acetate molecules; Rcryst = 21.6%; Rfree = 22.6% for 8% of the reflections removed at random; no σ cutoff}. The adamantyl moiety of Ru-C9-Ad is well ordered, but static and/or dynamic disorder increases up the methylene chain toward the sensitizer, where only one of the three bpy ligands is well resolved. The ruthenium atom position was confirmed by the largest peak in the initial Fobs–Fcalc electron density map (4σ) and also by a peak in the Bijvoet difference Fourier map (calculated with coefficients |F+| − |F−| and phases φmodel − π/2), which identified all sulfur and metal atoms in the model. The final model has excellent stereochemistry (root-mean-square deviation from ideal bond lengths < 0.009 Å and ideal bond angles < 1.3o) with 90.3% of all residues in the most favored regions of φ/ϕ space, as defined by procheck (19). No residues fall in disallowed regions. Larger refined thermal (B) factors for Ru-C9-Ad (<B> = 48.2 Å2) compared with the overall model (<B> = 28.0 Å2; <B>mainchain = 19.4 Å2; <B>sidechain = 20.4 Å2) reflect the mobility and conformational heterogeneity of the bound [Ru(bpy)3]2+. The ribbon representation (Fig. 1) was generated with molscript (20) and raster3d (21).

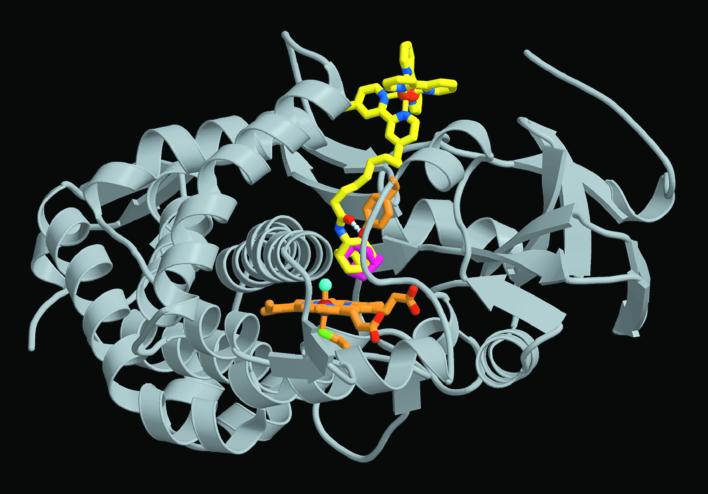

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of the P450cam:Ru-C9-Ad complex. The Ru substrate is shown in yellow to highlight docking of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ at the surface of the protein as predicted by computer modeling and energy-transfer experiments. The methylene linker occupies a large channel from the enzyme surface to the heme. A hydrogen bond connects the Ru-substrate amide carbonyl (red atom) to Tyr-96 (orange). The adamantyl moiety (center) resides at the P450 active site above the heme (orange) in the same position as the natural Ad substrate (magenta), shown in superposition from the 4cpp crystal structure (25). Although both Δ and Λ [Ru(bpy)3]2+ enantiomers are present in the complex, only Λ is shown.

Energy-Transfer Measurements.

Solution experiments were performed under an argon atmosphere with P450 and Ru substrate in 100 mM KCl/20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Single-crystal experiments were conducted aerobically. Samples were excited with XeCl excimer-pumped dye laser pulses (25 ns; 480 nm; 1–2 mJ per pulse). The emission decay traces were fit to the biexponential function, y = c0 + c1e−(ken + k0)t + c2e−k0t. The ratio c1:(c1 + c2) was used to calculate dissociation constants. Donor–acceptor spectral overlap gives a Förster distance (Ru-Fe distance at which half the emission is quenched by energy transfer; ref. 22) of R0 = 26.2 Å for the ferriheme enzyme and R0 = 27.6 Å for the carbonmonoxy species. Ru-Fe distances, r, were calculated by using the equation, ken = k0(R0/r)6.

Results and Discussion

Ru-substrates (Scheme S1) were modeled into the substrate-free P450 crystal structure (23) to position ethylbenzene (EB) and Ad at the active site and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ at the protein surface. Ru-Cn-EB and Ru-Cn-Ad were constructed by the covalent attachment of EB and Ad to variable length methylene chains [(CH2)7–13] terminating in the photosensitizer (6). An amide functionality was incorporated into the Ru substrates to permit hydrogen bonding, as occurs between Tyr-96 and camphor (15). To generate Ru-ligands that could bind the heme iron (24), imidazole was linked to alkyl-tethered [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (Ru-Cn-Im). Ru-EB/Ad compounds, as well as Ru-Im, have been shown to bind P450 with high affinity (6). We have crystallized one of these complexes, P450:Ru-C9-Ad, and structurally characterized it to 1.55 Å (Fig. 1). The Ru-substrate binds as predicted, with the Ad moiety mimicking substrate (25), a hydrogen bond between Tyr-96 and the amide functionality, and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ at the mouth of a large channel that has opened to accommodate the sensitizer.

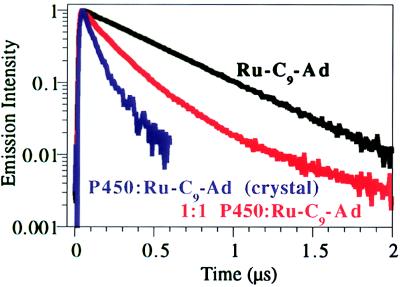

Binding of the Ru-Cn-EB/Ad/Im compounds to the P450 target was detected by decreases in Ru2+ excited-state (Ru2+*) lifetimes (6). [Ru-substrate]2+* emission decay is normally monophasic (k0 = 2.1 × 106 s−1) but becomes biphasic with a dominant fast component (ken = 0.5 × 107 to 1.4 × 107 s−1; k0 = 2.1 × 106 s−1) in the presence of P450 (Fig. 2). Thus, on addition of enzyme, the Ru-substrate or Ru-ligand partitions between a “bound” state, in which Ru2+* is quenched, and a “free” state, in which it is not. Photoexcitation of a P450:Ru-C9-Ad single crystal yields a predominantly monophasic luminescence decay (Fig. 2) that is strongly quenched by the protein (ken = 1.1 × 107 s−1), thereby confirming that the fast decay component, ken, is attributable to P450:Ru-substrate complex formation.

Figure 2.

Kinetics traces of [Ru-C9-Ad]2+* emission decay at room temperature in solution and in a single crystal of P450cam:Ru-C9-Ad. [Ru-C9-Ad]2+* (10 μM) shows monophasic decay (black). Emission decay of [Ru-C9-Ad]2+* equimolar with P450 (10 μM) is biphasic (red). In a P450:Ru-C9-Ad crystal, [Ru(bpy)3]2+* quenching is predominantly monophasic (blue). A secondary (<10%) slower phase (k0 = 4.8 × 106 s−1) also was observed, suggesting that a small percentage of the Ru substrate may remain unbound in the crystal. Faster [Ru(bpy)3]2+* emission decay, ken, in the crystal relative to solution most likely reflects small conformational differences in P450 between the two phases. Faster decay of the intrinsic [Ru(bpy)3]2+* emission, k0, in the crystal is attributable to quenching by oxygen.

Competitive binding between Ru-substrates and camphor at the active site is indicated by the ability of the natural substrate (KD ≈ 1 μM) to diminish the fraction of bound [Ru substrate]2+* decaying at the faster rate, ken. At the titration end point, camphor completely displaces the Ru-substrate from P450, as shown by monophasic Ru2+* emission decay kinetics (k0 = 2.1 × 106 s−1). Analysis of Ru-C11-Ad emission quenching by P450 yields a dissociation constant (KD = 0.8 μM) in excellent agreement with Ru-C11-Ad/camphor competitive binding assays monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy (KD = 0.7 μM). Association of Ru-substrates and Ru-ligands with P450 is sufficiently strong to allow detection of the enzyme at submicromolar concentrations (Table 1). The emission decay profile of Ru-C9-Ad (2.5 μM) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) is monophasic (k0 = 2.1 × 106 s−1) in the presence of six heme proteins (yeast cytochrome c, horse skeletal muscle myoglobin, bovine lipase cytochrome b5, bovine liver catalase, recombinant yeast cytochrome c peroxidase, and horseradish peroxidase), each at 5 μM. Our finding that the addition of 500 nM P450cam to this mixture yields biphasic Ru2+* kinetics (≈10% ken; ≈90% k0) indicates the feasibility of detecting specific biomolecules in complex media.

Table 1.

Dissociation constants, Ru2+* excited-state lifetimes, and Ru-Fe distances

| Compound | KD, μM | ken−1, ns | Ru-Fe, Å |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Ru-C13-EB]2+* | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 107 ± 8 | 20.6 ± 0.2 |

| [Ru-C12-EB]2+* | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 103 ± 7 | 20.5 ± 0.2 |

| [Ru-C11-EB]2+* | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 94 ± 7 | 20.1 ± 0.3 |

| [Ru-C10-EB]2+* | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 88 ± 2 | 19.9 ± 0.1 |

| [Ru-C9-EB]2+* | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 75 ± 2 | 19.4 ± 0.1 |

| [Ru-C7-EB]2+* | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 77 ± 2 | 19.5 ± 0.1 |

| [Ru-C11-Ad]2+* | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 203 ± 16 | 21.0 ± 0.3 |

| [Ru-C9-Ad]2+* | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 231 ± 11 | 21.4 ± 0.2 |

| [Ru-C13-Im]2+* | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 190 ± 8 | 21.2 ± 0.1 |

| [Ru-C11-Im]2+* | — | 488 ± 35 | NA |

Uncertainties represent one standard deviation of the data averaged from three to six experiments.

Specificity of Ru substrates for P450 is controlled largely by interactions of the substrate moiety with the active site. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that [Ru(bpy)3]2+ is a sensitive reporter of binding even for substrates that do not shift the heme absorption spectrum by displacing ligated water (6). Dissociation constants for Ru-Cn-EB compounds are the first presented for derivatives of EB. The chain-length dependence of binding in the Ru-Cn-EB series (KD = 0.7–6.5 μM for n = 7–13) shows that detection of P450 by Ru-substrates may be fine tuned by modification of the linker component. In the case of Im-terminated tethers, however, Ru-C11-Im has no affinity for P450, whereas Ru-C13-Im binds the enzyme tightly (Table 1). Apparently, the shorter linker does not allow the Im to extend far enough into the protein to ligate the heme iron.

Förster (dipole–dipole) energy transfer dominates the quenching in P450:Ru-substrate complexes. Evidence that electron transfer does not contribute significantly to this quenching is provided by the finding that ferriheme reduction by [Ru(bpy)3]+ is ≈103 times slower than ken (6). Spectral overlap of [Ru(bpy)3]2+* emission with the absorption of Fe(CO)2+ P450 is greater than with the ferriheme enzyme, suggesting that Förster energy transfer should be more efficient in the carbonyl complex (where both oxidation and reduction of the heme–CO complex are energetically disfavored). Not only is the decay of Ru2+* in P450 Fe(CO)2+:Ru-C11-EB 1.5 times faster (ken = 1.6 × 107 s−1), the calculated Ru-Fe distances differ by only 0.4 Å for the two heme oxidation states (26, 27).

The Ru-Fe distance found in the P450:Ru-C9-Ad crystal (21 Å) is in excellent agreement with the Förster analysis of energy-transfer kinetics for this complex in solution. Similar Ru-Fe distances were calculated for the various Ru-substrates, suggesting a common mode of Ru-substrate binding at the P450 active site. The shallow Ru-Fe distance dependence on chain length in the Ru-Cn-EB series confirms that [Ru(bpy)3]2+ always binds near the protein surface. The shortest EB derivatives, Ru-C7-EB and Ru-C9-EB, report the minimum length of the substrate access channel (19.5 Å). These data also indicate that the region occupied by the methylene linker represents the most likely path followed by natural substrates to access the P450 active center. The swath cut by Ru-substrates in P450 is a channel of considerable breadth (3–8 Å) and depth (≈20 Å).

We have developed a method of sensing specific biomolecules that involves tethering a photosensitizer to a molecule with high affinity for an active site. Analysis of Ru/heme Förster energy-transfer kinetics has revealed the dimensions and conformational flexibility of the access channel and probed the mechanism of substrate binding. This approach can be broadly expanded through a combinatorial approach to designing substrate moieties that target P450s as well as other enzymes, modifying sensitizers to produce desired signals, and optimizing linkages to enhance specificity or probe target conformations. Replacement of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ with osmium polypyridyl complexes (28) would tune the emission further toward the near infrared, thereby improving tissue penetration and optical detection over the background of scattered light from cellular components. The ability of sensitizer-linked substrates to detect proteins and perform photochemical oxidation and reduction reactions at specific enzyme active sites (6) opens avenues for intervention in metabolic processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. M. Bilwes for assistance with protein expression and crystallization, D. C. Rees for use of facilities and comments, S. G. Sligar for providing a P450cam vector, J. H. Dawson for several discussions, M. Machczynski for computational assistance, and the Stanford Synchrotron Research Laboratory for use of data collection facilities. I.J.D. is a National Institutes of Health predoctoral trainee (Grant GM08346). B.R.C. is a Helen Hay Whitney Postdoctoral Fellow. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant CHE9807150.

Abbreviations

- bpy

2,2′-bipyridine

- EB

ethylbenzene

- Ad

adamantane

- Im

imidazole

- ∗

excited state

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates of the P450:Ru-C9-Ad structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1qmq).

References

- 1.Tschirret-Guth R A, Medzihradszky K F, Ortiz de Montellano P R. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4731–4737. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortiz de Montellano P R, Correia M A. In: Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. 2nd Ed. Ortiz de Montellano P R, editor. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 305–364. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joo H, Zhanglin L, Arnold F H. Nature (London) 1999;399:670–673. doi: 10.1038/21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevenson J-A, Westlake A C G, Whittock C, Wong L-L. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:12846–12847. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulos T L, Cupp-Vickery J R, Li H. In: Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. 2nd Ed. Ortiz de Montellano P R, editor. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilker J J, Dmochowski I J, Dawson J H, Winkler J R, Gray H B. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkinson R N, Moore L, Tobin J, King S B. J Org Chem. 1999;64:3467–3475. doi: 10.1021/jo982161f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi Y, Fang X J, Szklarz G D, Halpert J R. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6679–6688. doi: 10.1021/bi9731450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukui T, Tanizawa K. Methods Enzymol. 1997;280:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)80099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy Y, Massey V. Methods Enzymol. 1997;280:436–460. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)80135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tschirret-Guth R A, Medzihradszky K F, Ortiz de Montellano P R. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7404–7410. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unger B P, Gunsalus I C, Sligar S G. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1158–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickerson D, Wong L-L, Rao Z H. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:470–472. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997012195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poulos T L, Finzel B C, Howard A J. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:687–700. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McRee D E. J Mol Graphics. 1992;10:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thornton J M. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merritt E A, Bacon D J. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Förster T. In: Modern Quantum Chemistry. Sinanoglu O, editor. Vol. 3. New York: Academic; 1965. pp. 93–137. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poulos T L, Finzel B C, Howard A J. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5314–5322. doi: 10.1021/bi00366a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawson J H, Andersson L A, Sono M. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:3606–3617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raag R, Poulos T L. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2674–2684. doi: 10.1021/bi00224a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Förster T. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1959;27:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galley W C, Stryer L. Biochemistry. 1969;8:1831–1833. doi: 10.1021/bi00833a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kober E M, Marshall J L, Dressick W J, Sullivan B P, Caspar J V, Meyer T J. Inorg Chem. 1985;24:2755–2763. [Google Scholar]