Abstract

Auto-antibodies against the β1-adrenoceptors are present in 30−40% of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Recently, a synthetic peptide corresponding to a sequence of the second extracellular loop of the human β1-adrenoceptor (β1-ECII) has been shown to produce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, myocyte apoptosis and cardiomyopathy in immunized rabbits. To study the direct cardiac effects of anti-β1-ECII antibody in intact animals and if they are mediated via β1-adrenoceptor stimulation, we administered IgG purified from β1-ECII–immunized rabbits to recombination activating gene 2 knock-out (Rag2−/−) mice every two weeks with and without metoprolol treatment. Serial echocardiography and cardiac catheterization showed that β1-ECII IgG reduced cardiac systolic function after 3 months. This was associated with increase in heart weight, myocyte apoptosis, activation of caspase-3, -9 and -12, and increased ER stress as evidenced by upregulation of GRP78 and CHOP and cleavage of ATF6. The Rag2−/− mice also exhibited increased phosphorylation of CaMKII and p38 MAPK. Metoprolol administration, which attenuated the phosphorylation of CaMKII and p38 MAPK, reduced the ER stress, caspase activation and cell death. Finally, we employed the small-interfering RNA technology to reduce caspase-12 in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. This reduced not only the increase of cleaved caspase-12 but also of the number of myocyte apoptosis produced by β1-ECII IgG. Thus, we conclude that ER stress plays an important role in cell death and cardiac dysfunction in β1-ECII IgG cardiomyopathy, and the effects of β1-ECII IgG are mediated via the β1-adrenergic receptor.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, endoplasmic reticulum, metoprolol, severe combined immunodeficiency mouse, apoptosis, MAP kinase, caspase-12 small-interfering RNA

1. Introduction

Auto-antibodies against the β1-adrenergic receptors, present in 30−40% of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (1, 2), have been postulated to play an important role in the pathogenesis of human cardiomyopathy (3). This hypothesis is further supported by 3 major findings: 1) the antoantibodies exert agonistic and apoptotic effects in cultured cardiomyocytes (1, 4-6), 2) immunization with a synthetic peptide corresponding to a sequence in the second extracellular loop of the human adrenergic receptor (β1-ECII) produces cardiomyopathy in a number of experimental animals (7-10), and 3) removal of anti-β1-ECII antibodies improves cardiac function in the rabbit β1-ECII cardiomyopathy (11), and human dilated cardiomyopathy (12). Furthermore, isogenic transfer of sera from rats immunized with the β1-ECII peptide to healthy littermates produces cardiac morphology similar to the cardiomyopathic changes in the donor rats (9). However, because the sera may contain cytotoxic cytokines and biologically active humoral factors other than the anti-β1-ECII antibody, we proposed to obtain immunoglobulin (Ig) G from the sera of cardiomyopathic rabbits, and study the direct effects of purified IgG in the recombination activating gene-2 (Rag2) deficiency mice. Homozygous Rag2−/− mice exhibit total inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement and fail to generate mature T and B lymphocytes (13), making it a widely accepted animal model for adoptive transfer experiments. The severe combined immunodeficiency mouse has been used to demonstrate a pathogenic role of peripheral blood leukocytes from patients with myocarditis (14) and dilated cardiomyopathy (15). Transfer of IgG and/or peripheral blood lymphocytes from rabbit autoimmune cardiomyopathy to severe combined deficiency mice has been shown to increase heart weight, blood brain natriuretic peptide and focal infiltration of inflammatory cells in the myocardium (16).

In addition, to determine if β1-ECII IgG exerts its effects via the β1-adrenergic receptor and its post-receptor effectors, Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), we also studied the effects of β1-ECII IgG in Rag2−/− mice with chronic metoprolol administration. Since the β1-adrenergic stimulation has been shown to induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and cell apoptosis (17) and inhibit the phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase/Akt survival pathway (18), we also sought to determine the transcriptional and translational induction of 78 kDa glucose regulated protein (GRP78) and C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), activation of ATF6, and processing of ER-resident caspase-12, as well as the functional state of Akt and its downstream GSK3β in the β1-ECII treated Rag2−/− mice with and without metoprolol treatment. Finally, to determine the functional importance of caspase-12 in the β1-ECII IgG-induced myocyte apoptosis, we carried out experiments in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes using small-interfering RNA (siRNA) technology to inhibit caspase-12 synthesis.

2. Methods

2.1. Rag2−/− animals and experimental design

Experiments were performed in male transgenic Rag2−/− mice (Taconic Farms, Inc., Hudson, NY). The experimental protocol was approved by the University of Rochester Committee on Animal Resources and conformed to the guiding principles approved by the Council of the American Physiological Society and the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use Laboratory Animals (DHHS Publication No. [NIH] 85−23, Revised 1996, Office of Science and Health Reports).

Rag2−/− mice were randomly divided into 4 groups: 1) Control group, receiving no rabbit IgG; 2) β1-ECII group, receiving β1-ECII IgG (100 μg/g, intraperitoneally) every 2 weeks; 3) β1-ECII plus metoprolol group, receiving both β1-ECII IgG and subcutaneous metoprolol pellet (2.5 mg, 90 day release; Innovative Research of America, Saratoga, FL); 4) Metoprolol group, receiving metoprolol pellet alone. All animals were studied for 12 weeks. Metoprolol pellets were implanted subcutaneously 1−2 days before start of IgG administration. This dose of metoprolol is well-tolerated by the animals, and is large enough to block the inotropic effect of dobutamine at the end of experiment. β1-ECII IgG was purified from the sera of New Zealand White rabbits after 6 months of immunization with a synthetic β1-ECII peptide (17), using Montage antibody purification kits with PROSEP-G spin columns (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The IgG fraction is judged highly purified by SDS-PAGE showing only two bands (∼55 kDa and ∼26 kDa) corresponding to the heavy chain and the light chain, respectively. ELISA shows a high (1:8000) anti-β1-ECII titer of the IgG. The protein concentration was determined using BCA Protein Assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL).

The animals were studied by echocardiography at Week 0 and Week 12. At the end of study, the animal was anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, and the heart harvested. The left ventricle including the interventricular septum was removed, rinsed in ice-cold oxygenated saline, and quickly stored in liquid nitrogen. Some animals were anesthetized and instrumented for hemodynamic studies as described below.

2.2. Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed on gently restrained mice using an Acuson Sequoia C256 imaging system (Mountain View, CA) and a 13-MHz broadband transducer by an experienced echocardiographer blinded to the animal treatment assignment. LV fractional shortening was measured as follows: LV fractional shortening = [(LV end-diastolic dimension – LV end-systolic dimension) × 100]/LV end-diastolic dimension.

2.3. Hemodynamic measurements

Animals were anesthetized intraperitoneally with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (2.5 mg/kg), and covered with a thermal blanket to keep rectal temperature normal. A Model SPR-621 1.4 Fr Millar Mikro-Tip pressure transducer (Millar Instruments Co., Houston, TX) was inserted into the right carotid artery and advanced into LV. Heart rate, aortic pressure, LV pressure and its maximal rate of rise (dP/dt) were recorded on an IOX data acquisition and analysis system (EMKA Technologies, Inc., Falls Church, VA). The left jugular vein was cannulated for venous access. At least 30 minutes were allowed to elapse after the catheterizations before the resting hemodynamic data were taken in triplicate over a 10-min steady state. Each set of measurements was taken from averages of data over 5 seconds. Dobutamine was then infused at successively increasing doses of 5, 10, 20 and 40 μg/kg/min, each for 5 min, using a CMA/102 microdialysis pump (CMA Microdialysis, North Chelmsford, MA). Hemodynamic data were obtained over 20 seconds at the end of each infusion and averaged for statistical analysis.

2.4. TUNEL apoptosis assay

The TUNEL assay was performed on paraffin-embedded myocardial tissue slides using an Apoptosis Detection System (Promega, Madison, WI), as described recently (17). The number of TUNEL-positive cells was measured by counting cells exhibiting green fluorescent nuclei at ×20 power in 10 randomly chosen fields in triplicate sections under an Olympus BX-FLA reflected light fluorescence microscope (Olympus Imaging America Corp., Melville, NY). Apoptosis index is defined as the number of TUNEL-positive cells per 1×105 cardiomyocytes.

2.5. RNA extraction and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from ventricular myocardium using GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and subjected to reverse transcription using the Enhanced Avian RT First Strand Synthesis Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The single strand cDNA was then amplified by PTC-100 Thermal Cycler (MJ Research, Inc, Waltham, MA), using the appropriate primers and Tag DNA polymerase mixture (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Amplification reactions were carried out under an optimal condition for the following primers: for GRP78: sense 5′-GAAAGGATGGTTAATGATGCTGAGAAG-3′; anti-sense 5′-GTCTTCAATGTCCGCATCCTG-3′; and for CHOP: sense 5′-GCATGAAGGAGAAGGAGCAG-3′; anti-sense 5′- CTTCCGGAGAGACAGACAGG-3′; and for the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH): sense 5′-GCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3′; anti-sense 5′-GGCCATCCACAGTCTTCT-3′. Amplification products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide and visualized by UV irradiation in a GELDOC-IT Imaging and Analysis Apparatus (UVP, Inc., Upland, CA).

2.6. Western blotting protein assays

Ventricular muscle was prepared for Western blot analysis as described previously (17). Protein (20 μg) was denatured by heating at 95 °C for 5 min in SDS sample buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA), loaded onto 10−12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and then transferred electrically to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk 0.1% Tween TBS buffer for 1 h, and were then incubated overnight with the following antibodies: Anti-GRP78 (1:1000, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-CHOP, anti-ATF6 (1:2,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), anti-caspase 12 (1:500 Sigma-Aldrich), anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), anti-phospho-p44/42 ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), anti-phospho-p54/46 SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), anti-p38 MAPK, anti-p44/42 ERK, anti-SAPK/JNK, anti-phospho-Akt (Thr308), anti-phospho-GSK3β (Ser9), anti-Akt, anti-GSK3β, anti-caspase 9, anti-caspase 3 (all 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-phospho-CaMKII (Thr286) (1:500, Affinity BioReagents, Inc., Golden, CO), and anti-CaMKII (1:1,000, Upstate, Inc., Charlottesville, VA). The membrane was then washed, treated with secondary antibody, and visualized using an ECL system (Cell Signaling Technology). Anti-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to confirm equal loading. The immunoblots were read on a Microtek ScanMaker (Microtek, Inc., Carson, CA), using NIH 1.6 Gel Image Software, and the readings were normalized to a control sample in an arbitrary densitometry unit.

2.7. Cultured rat cardiomyocytes

Cardiac ventricles, taken from 1−2 day old Sprague-Dawley rat neonates, were gently minced and enzymatically dissociated using collagenase H (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ). Cells were collected by centrifugation and plated at a density of 5 × 104/cm2 on a 60-mm dish in DMEM (Cellgro®, Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA). To measure the functional role of caspase-12 on cell apoptosis, we carried out experiments in the cultured cardiomyocytes after transfection with 27-mer siRNA Dicer duplexes designed by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA), according to the rat procaspase-12 RNA sequence (Accession number NM_130324, position 813−837). The synthetic Dicer-substrate RNAs show increased potency and efficacy compared to their comparable 21-mer duplexes (19). To transfect the cells, the siRNA Dicer duplexes were first mixed with FuGENE-6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Nutley, NJ) for 15 min at room temperature, and then added to the cells in Opti-MEM medium (GIBCO, Invitrogen Corp.) with the final concentration of 0.4 μM of the oligonucleotides for 24 h. Cells were then incubated with ß1-ECII IgG (200 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 48 h, and assayed for p-p38 MAPK, CHOP, and caspase-12 proteins and TUNEL-positive cells.

2.8. Statistics

Experimental data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and results are expressed as means±SEM. One-way ANOVA was used to determine the significance of differences among the experimental groups. The statistical significance of differences between 2 groups was determined using a Bonferroni post hoc test. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Echocardiogram and hemodynamics

The Rag2−/− mice exhibited no respiratory distress, gross edema, or agitation from the β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol administration during the 3 months of study. Table 1 shows that body weight did not differ among the 4 groups by the end of the study. There was also no significant difference in lung or liver weight. However, heart weight differed significantly among the experimental groups (F = 6.72, d.f.=3, 40, P<0.001). It was increased 20% in the β1-ECII IgG-treated animals compared to the control animals. This difference was accentuated when heart weight was normalized to body weight in the animals. Metoprolol treatment largely abolished the increase in heart weight. Notably, metoprolol alone did not have any effect on heart weight in the Rag2−/− animals.

Table 1.

Morphological and hemodynamic changes in transgenic Rag2−/− mice following 12 weeks of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol administration

| Control | IgG | IgG+Metoprolol | Metoprolol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | ||||

| Body weight (g) | 27.3±1.3 | 25.9±1.2 | 25.2±1.1 | 28.2±2.6 |

| Heart weight (mg) | 155±6 | 186±6* | 167±10 | 158±13 |

| Heart/body weight (mg/g) | 5.8±0.3 | 7.2±0.2* | 6.6±0.2 | 5.7±0.3 |

| Lung (g) | 0.20±0.01 | 0.20±0.01 | 0.22±0.02 | 0.23±0.02 |

| Liver (g) | 1.29±0.06 | 1.26±0.08 | 1.28±0.09 | 1.38±0.09 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 205±23 | 274±32 | 199±17 | 184±11 |

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 79±3 | 88±9 | 85±6 | 76±4 |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 1.7±0.5 | 12.0±1.3* | 3.1±1.4† | 1.8±0.7† |

| LV dP/dt (mmHg/s) | ||||

| Resting | 5335±251 | 4034±531 | 4282±465 | 5347±549 |

| Dobutamine (Δ) | 6848±771 | 3454±798* | 1192±682* | 3540±691* |

Values are means±SEM. N=6−19. One-way analysis of variance and post-hoc multiple comparison tests with Bonferroni corrections were used to determine the statistical significance of differences among the 4 groups. BP=blood pressure. EDP=end-diastolic pressure.

P<0.05, compared to the Control group.

P<0.05, compared to the β1-ECII IgG group. The increases in LV dP/dt shown with dobutamine infusion were based on the highest dose (40 μg/kg/min) of the drug.

LV fractional shortening averaged 59.5% at baseline, and did not differ among the 4 groups. As heart weight increased over the 12 weeks, LV fractional shortening decreased 12.4±2.3% in the β1-ECII IgG-treated animals. Metoprolol partially reversed the decrease in LV fractional shortening to 6.4±2.8%. In contrast, LV fractional shortening did not change significantly in either the control (−1.3±2.7%) or the metoprolol alone group (−3.8±2.0%).

Table 1 also shows the resting hemodynamics in the anesthetized animals at the end of study. The animals showed no significant differences in resting heart rate, mean aortic blood pressure, or LV dP/dt among the 4 groups. In the unanesthetized state, heart rate was higher, ranging from 500 to 734 beats/min, but also showed no significant differences among the 4 experimental groups (F=1.43, d.f.=3, 33, P=0.25). LV end-diastolic pressure was elevated significantly in the β1-ECII IgG animals compared to the other groups. Metoprolol treatment, which had no direct effect on LV end-diastolic pressure when given alone, completely prevented the increase in LV end-diastolic pressure in the β1-ECII IgG animals.

Dobutamine infusions increased LV dP/dt in the experimental animals. In Control animals, LV dP/dt increased 21±9% during the first dose of dobutamine (5 μg/kg/min), and rose gradually to 72±16%, 119±19%, and 147±19% above the baseline during the 3 successively increasing doses (10, 20 and 40 μg/kg/min). However, the increases in LV dP/dt were much smaller in the β1-ECII IgG animals. LV dP/dt did not increase significantly until the animals were given 20 and 40 μg/kg/min of dobutamine. The increase in LV dP/dt was also significant attenuated by chronic metoprolol treatment, particularly in those also treated with β1-ECII IgG. Table 1 shows that statistically significant differences exist in the net increases of LV dP/dt produced by the highest dose of dobutamine (40 μg/kg/min) among the 4 experimental groups.

3.2. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis

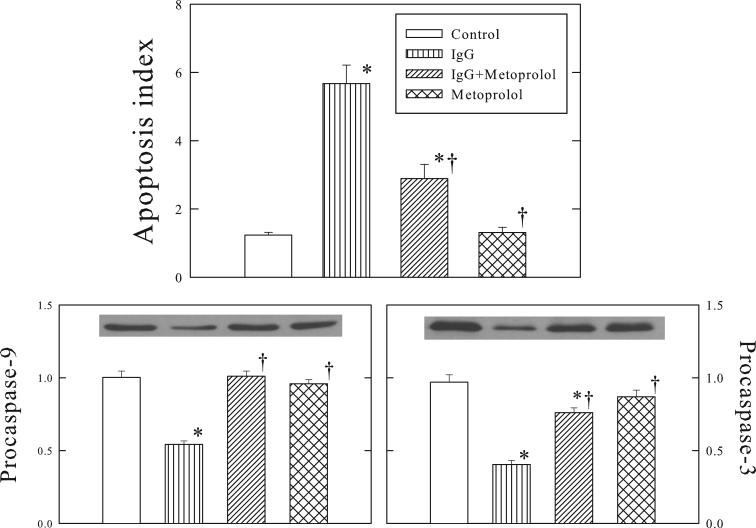

Figure 1 shows that apoptosis index increased 4 fold in the β1-ECII IgG group compared to the Control group. Myocyte apoptosis was further confirmed by the activation of proapoptotic caspase-3 and -9, as evidenced by the decrease of procaspase-3 and -9 (Figure 1). Metoprolol treatment, which had no effects when given alone, attenuated the increase of apoptosis index and reductions of procaspase-3 and -9 in the β1-ECII IgG animals.

Figure 1.

Effects of β1-ECII immunoglobulin G (IgG) and metoprolol on cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and activation of caspase-9 and -3 in Rag2−/− mice. Representative Western blots are shown for caspase-9 and -3. The optical density is expressed in arbitrary units normalized against a control sample. Bars denote SEM. N=6−8. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

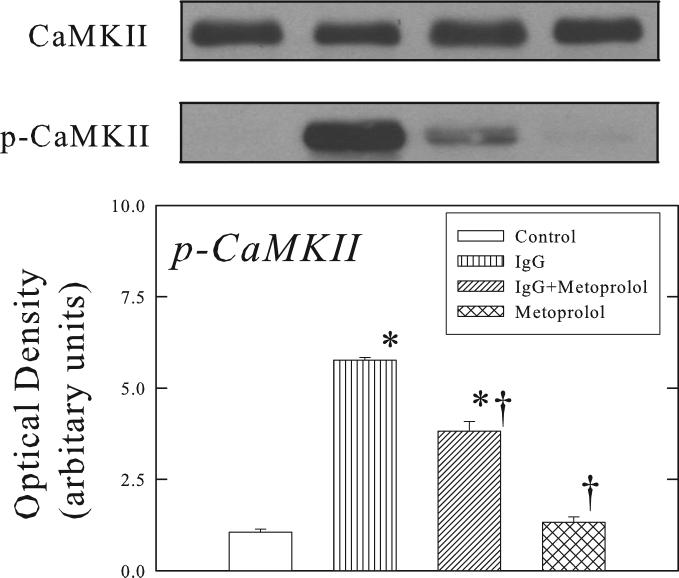

3.3. Activation of the CaMKII and MAPK pathways

β1-ECII IgG treatment produced a 12-fold increase in phosphorylation of CaMKII in the ventricular myocardium, and that this effect was attenuated by metoprolol pellet (Figure 2). Importantly, neither β1-ECII IgG nor metoprolol treatment produced any changes in total CaMKII.

Figure 2.

Effects of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol on CaMKII and p-CaMKII in Rag2−/− mice. The optical density is expressed in arbitrary units normalized against a control sample. Representative Western blots shows that unlike p-CaMKII, CaMKII was not affected by β1-ECII IgG. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

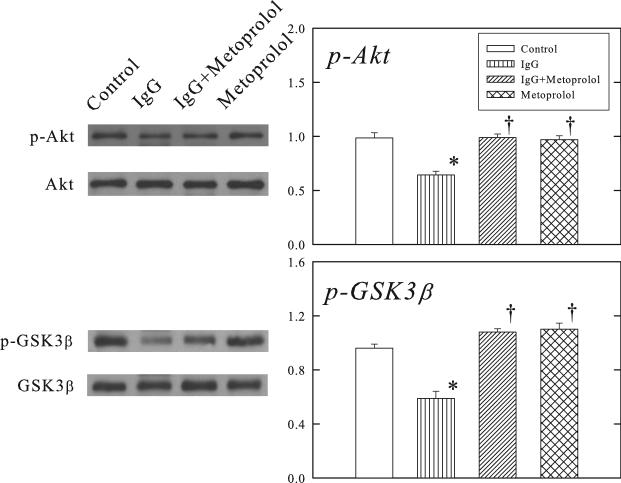

Figure 3 shows that parallel to the changes of p-CaMKII, the protein expressions of the phosphorylated p38 MAPK and JNK were increased by β1-ECII IgG, and the increases were reduced by metoprolol treatment. In contrast, ERK phosphorylation was reduced by β1-ECII IgG and this was reversed by metoprolol treatment as well. Total p38 MAPK, JNK and EKR did not differ among the 4 groups.

Figure 3.

Effects of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol on MAPKs in Rag2−/− mice. Representative Western blots are shown on the left panel. The group data are shown in the bar graphs. The optical density is expressed in arbitrary units normalized against a control sample. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

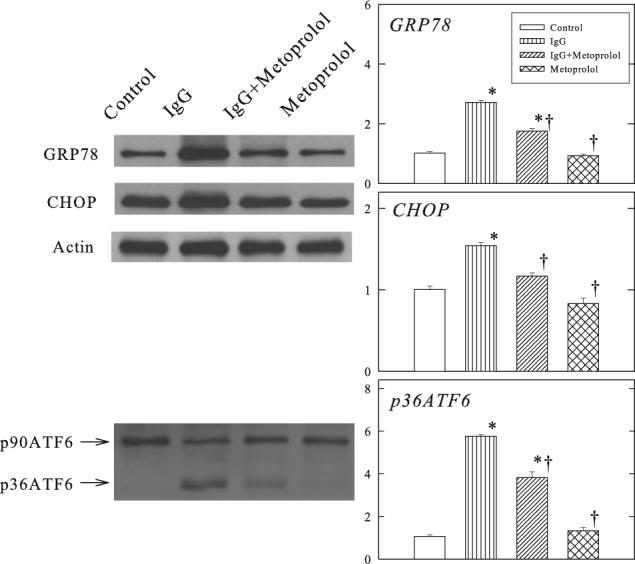

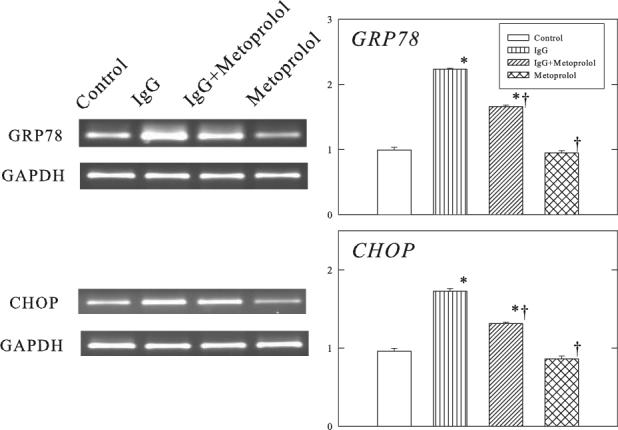

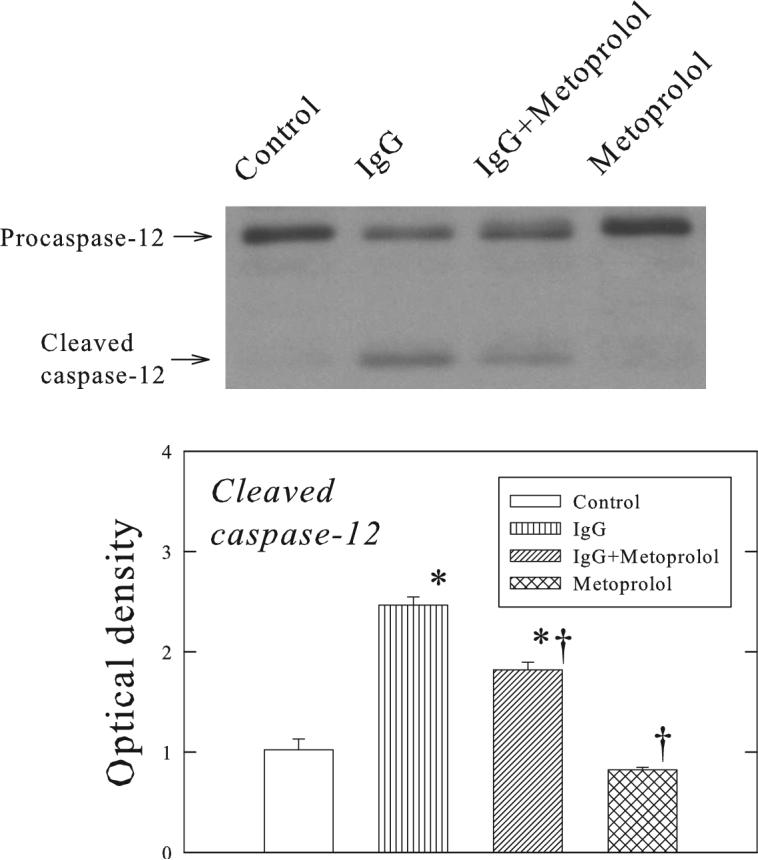

3.4. Endoplasmic reticulum function

Figure 4 shows the changes in GRP78, CHOP and ATF6 proteins in the ventricular muscle of Rag2−/− mice. Administration of β1-ECII IgG increased GRP78, CHOP, and cleavage of full-length ATF6 to smaller p36ATF6. The gene expressions of GRP78 and CHOP were also increased (Figure 5). Furthermore, procaspase-12 was activated resulting in cleavage of procaspase-12 to smaller cleaved caspase-12 (Figure 6). Metoprolol treatment attenuated but did not abolish the changes in GRP78, CHOP, p36ATF6, and cleavage of procaspase-12 in the β1-ECII IgG animals.

Figure 4.

Effects of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol on GRP78, CHOP and ATF6 proteins in Rag2−/− mice. Representative Western blots are shown on the left panel. Anti-actin was used to show equal loading. β1-ECII IgG treatment caused cleavage of p90ATF6. Group data are shown in the bar graphs. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

Figure 5.

Effects of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol on GRP78 and CHOP mRNA in Rag2−/− mice. GAPDH was used as a marker for equal loading. Group data in arbitrary optical density units are shown in the bar graphs. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

Figure 6.

Effects of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol on the processing of caspase-12 in Rag2−/− mice. The representative Western blot shows the increased cleavage of caspase-12 by β1-ECII IgG, and reduction of the increased cleavage by metoprolol. Group data in arbitrary optical density units for the cleaved caspase-12 are shown in the bargraph. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

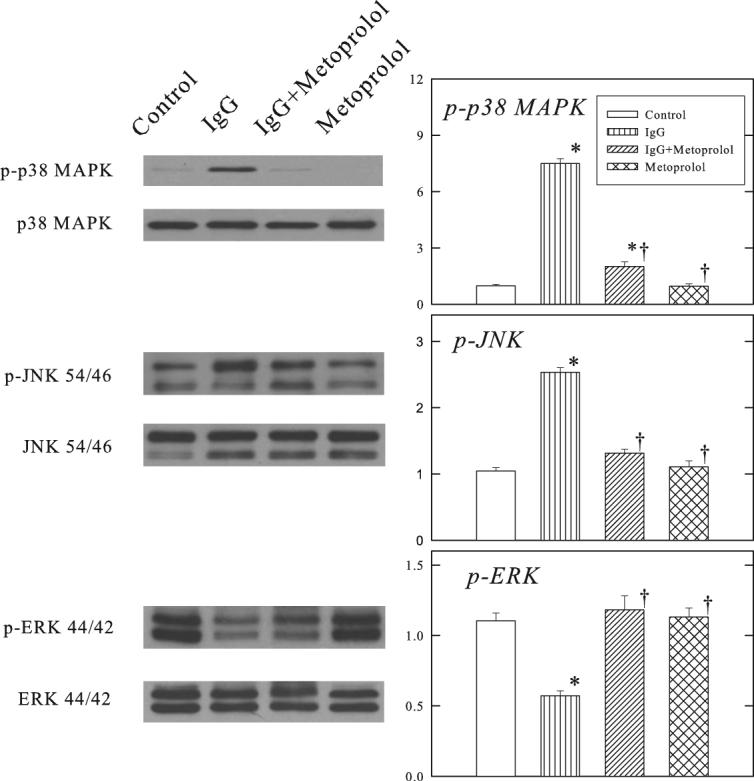

3.5. Phosphorylation of Akt and GSK3β

Figure 7 shows that β1-ECII IgG treatment reduced phosphorylated Akt and GSK3β in the ventricular myocardium of Rag2−/− mice, and that these changes were prevented by coadministration of metoprolol.

Figure 7.

Effects of β1-ECII IgG and metoprolol on Akt and GSK3β phosphorylation in Rag2−/− mice. Representative Western blots are shown on the left panel. Group data in arbitrary optical density units for p-Akt and p-GSK3β are shown in the bargraphs. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG.

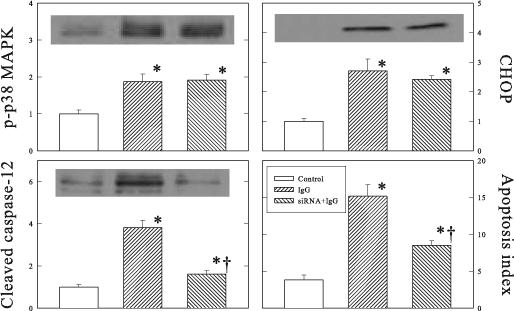

3.6. Caspase-12 siRNA in cultured rat cardiomyocytes

β1-ECII IgG increased p38 MAPK phosphorylation, and caused CHOP up-regulation, caspase-12 activation, and myocyte apoptosis in the cultured neonatal rat cardiomyopathy (Figure 8). As expected, inhibition of caspase-12 synthesis by siRNA reduced procaspase-12 and cleaved caspase-12 in the cultured cardiomyocytes. It also reduced the amount of TUNEL-positive cells, but had no effect on p-p38 MAPK or CHOP.

Figure 8.

Effects of caspase-12 siRNA on β1-ECII–induced increases of p38 MAPK, CHOP, cleaved caspase-12 and cell apoptosis in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Representative Western blots are shown for p-p38 MAPK, CHOP, and cleaved caspase-12. Group data are shown in arbitrary optical density units. Bars denote SEM. N=6. *P<0.05, compared to Control. †P<0.05, compared to β1-ECII IgG without siRNA.

4. Discussion

The present study shows that adoptive passive transfer of β1-ECII IgG from rabbits with autoimmune cardiomyopathy produced cardiomyopathic changes in severe combined immunodeficiency mice. Since the transgenic animal lacks the capacity to mount T-cell and B-cell response, our study proves that the effect of β1-ECII IgG in the recipient animals is a direct result of the biologically active anti-β1ECII antibody. Also, neither proinflammatory cytokines nor complement-dependent cytolysis plays a major role in the development of dilated cardiomyopathy. Our findings extend the earlier findings that isogenic transfer of sera from autoimmune rats to healthy littermates produced cardiomyopathic changes (9). We have further demonstrated that the cardiomyopathic changes produced by β1-ECII IgG are linked to CaMKII and MAPK activation and ER stress-related apoptosis. Finally, since the effects were abolished by metoprolol, β1-ECII IgG probably exerts its action via an agonist action on the β1-adrenergic receptor. The present study is unique in that purified IgG was used to demonstrate the mechanisms of action in intact severe combined immunodeficiency mice, and that caspase-12 siRNA was used to determine the functional importance of the ER-specific caspase-12 directly in the cultured cardiomyocytes for the apoptotic effects of anti-β1-ECII antibody. These findings establish conclusively a direct role of anti-β1-ECII antibody on ER stress and dilated cardiomyopathy.

Administration of β1-ECII IgG produced multitudes of cardiac dysfunction in the Rag2−/− animals. At organ level, the heart weight increased significantly over the control. Impaired cardiac function was evidenced by the elevated LV end-diastolic pressure, lower LV dP/dt at rest and reduced LV dP/dt response to intravenous dobutamine. At cellular level, cardiac cell death was demonstrated by the increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes and activations of caspase-3 and -9. However, these animals exhibited no significant increase in lung or liver weight, suggesting the cardiomyopathy induced by this protocol of β1-ECII IgG treatment is relatively mild and early in its development.

The β1-ECII peptide used to immunize rabbits in our study has been employed by us and other investigators to produce autoimmune cardiomyopathy (7-10). A protein homology scanning analysis of the human β1-adrenoceptor has shown that only the β1-ECII fragment contains B- and T-cell epitopes and is easily accessible to antibodies (20). The β1-ECII IgG purified from our β1-ECII-immunized rabbits showed a high anti-β1-ECII antibody titer. The IgG from β1-ECII immunized rabbits also has been shown to be specific with no cross reactions with either β2-adrenoceptor or other G-protein coupled receptors (7). In the latter study, β1-ECII immunization induced morphological changes in the heart similar to those found in the human dilated cardiomyopathy. The specificity of the antibody on the β1-adrenoceptor was confirmed in our study by the marked attenuation of the β1-ECII IgG-induced cardiomyopathic changes by metoprolol. Similarly, β1-receptor blockade by bisoprolol has been shown to reduce the cardiomyopathic changes in β1-ECII-immunized rabbits (21). Finally, the receptor-specific affinity of the anti-β1-ECII antibody raised in rabbits was supported by immunoabsorption with β1-adrenoceptor peptide column which removed anti-β1-ECII autoantibodies and thereby improved cardiac structure and function in experimental autoimmune cardiomyopathy (11).

The β1-ECII antibody has been shown to stimulate the β1-adrenoceptor and increase cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) acutely in cultured cardiomyocytes, and these effects are abolished by metoprolol (6). Previously, cAMP/PKA was thought to play a role in the β1-adrenergically induced myocyte apoptosis (22). However, evidence now exists that the β1-adrenergically induced myocyte apoptosis is not PKA dependent (23). Instead, the cardiac effects of sustained β1-adrenergic stimulation are associated with a cAMP-independent increase of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of CaMKII (24). This increase in intracellular Ca2+ probably is caused by a direct coupling of the α subunit of the stimulatory heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding G protein to the Ca2+ channel (25). Cardiomyopathic changes in ß1-adrenoceptor-overexpressing transgenic animals also could be rescued by phospholamban ablation which normalizes diastolic calcium levels (26), confirming that increased intracellular Ca2+ is critical for the detrimental effects of β1-adrenergic stimulation (27). Our present study showed that β1-ECII IgG increased CaMKII phosphorylation and myocyte apoptosis. We also observed an increase of Ca2+ transient by β1-ECII IgG in cultured cardiomyocytes (unpublished observations). Since these changes are abolished by metoprolol, β1-ECII IgG probably stimulates CaMKII via increased intracellular calcium following β1-adrenoceptor stimulation.

Elevated intracellular Ca2+ also stimulates the ER. ER is a multifunctional signaling organelle with sophisticated stress-signaling pathways that control not only the entry and release of Ca2+, but also sterol biosynthesis, membrane protein translocation, and apoptosis (28). The ER response to stress consists of 2 sequences of events known as unfolded protein response (UPR) and ER overload response (EOR) (29, 30). Experimentally, ER stress can be induced by a variety of unrelated stimuli, such as thapsigargin which inhibits Ca++-ATPase, glucose deprivation, azetidine, tunicamycin, and oxygen free radicals (31-33). However, the exact pathways by which the stimuli induce ER stress may differ. For example, the ER stress induced by azetidine is linked to the p38 MAPK pathway, whereas the induction of ATF6 and GRP78 by thapsigargin can still occur when the p38 MAPK pathway is blocked by drug inhibitors or domain negative mutant of p38 MAPK (34).

The UPR is characterized by early phosphorylation of the RNA-dependent protein-like ER kinase and the α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor-2, transcriptional upregulation of GRP78 and CHOP, and rapid reduction in protein biosynthesis aimed at lowering the load of client proteins (35). GRP78 is the most abundant ER chaperone (36). When ER stress occurs, it dissociates from p90ATF6, allowing ATF6 to translocate to the Golgi, where p90ATF6 is cleaved by S1P/S2P protease to smaller fragments, such as p50ATF6 and p36ATF6. The soluble ATF6 transactivation domain enters the nucleus and induces UPR target genes (37). This process is predominantly adaptive, aiming to restore ER homeostasis and protect the cell from stress. However, when the load of proteins overwhelms the capacity of ER in processing the load efficiently, the proapoptotic EOR ensues. The exact mechanisms by which EOR triggers cell death are not known, but probably involves transcriptional activation of CHOP, caspase-12, and the MAPK pathways (30, 37), as well as inhibition of the PI3-kinase/Akt survival pathway (18).

CHOP is a transcription factor involved in the ER (38, 39). While its downstream target genes for cell apoptosis are not fully understood, the Bcl-2 family (40) and a subset of caspase-7 and -12 (41, 42) are probably involved. Procaspase-12 is unique to the ER. It is activated to caspase-12 only by ER stress (41), which mediates cell death independent of Apaf-1, cytochrome c and mitochondria (42, 43).

Our results show that β1-ECII IgG triggered both the UPR and EOR responses in Rag2−/− mice, as evidenced by the increase in both mRNA and proteins expressions of GRP78 and CHOP, the increase in cleaved p36ATF6, and increased cleavage of procaspase-12. Also, like azetidine, anti-β1-ECII antibody induced ER stress in cardiomyocytes via phosphorylation of CaMKII and p38 MAPK. The apoptotic effects of anti-β1-ECII antibody are abolished by specific inhibitors of CaMKII and p38 MAPK (17). Furthermore, we found that inhibition of caspase-12 function by siRNA led to a marked reduction of the apoptotic effect of β1-ECII IgG. The findings suggest that caspase-12 activation is the predominant mechanism for cardiomyocyte apoptosis and production of autoimmune cardiomyopathy produced by β1β-ECII IgG. In addition, as caspase-12 siRNA produced no effects on p38 MAPK or CHOP, the β1-ECII IgG-induced activation of procaspase-12 is downstream from p38 MAPK phosphorylation and CHOP upregulation. Finally, since inhibition of caspase-12 did not completely abolish the induction of myocyte apoptosis, other proapoptotic mechanisms, such as oxidative stress and the intrinsic apoptotic pathway may exist and play a role in the production of cardiomyopathy in the β1-ECII IgG animals.

This study showed that ventricular myocardial JNK and p38 MAPK were activated by β1-ECII IgG. Prior studies (44-46) have shown that ER stress induces recruitment of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) to transmembrane protein kinase IRE1 and causes activation of JNK and p38 MAPK. In ASK1−/− cells, ER stress-induced phosphorylation of JNK was blocked and ER stress-induced apoptosis was significantly ameliorated (45). Recently, we (18) reported that norepinephrine suppressed the PI3-kinase/Akt survival pathway and reduced phospho-Akt in PC12 cells, and that nerve growth factor which promotes the PI3-kinase/Akt activity reduced the effect of norepinephrine on cell apoptosis and activation of caspase-12 and -3. We have further shown that this effect of norepinephrine is mediated via ER stress because similar changes are produced by thapsigargin. Results of our present study indicate that as demonstrated with norepinephrine in PC12 cells, β1-ECII IgG reduced the phosphorylation of Akt in the ventricular myocardium. This change in phospho-Akt was linked to reduction of phosphorylation of its downstream effector GSK3β, suggesting that GSK3β activity was increased, and might play a role in the apoptotic action (47) of β1-ECII IgG. Furthermore, since the changes in Akt and GSK3β were abolished by metoprolol, this inhibition of the PI3-kinase/Akt system is also mediated via β1-adrenergic receptors. However, further studies are needed to determine the pathophysiological importance of changes in this survival pathway in cardiomyopathy.

Autoantibodies directed against the β1-adrenoceptor have been shown to recognize a native β1-adrenoceptor conformation, impair the radioligand binding to the receptor, and affect receptor activity by divergent allosteric effects similar to those induced by agonist or partial agonist ligands (48). A recent study in murine dilated cardiomyopathy indicates that the β1-adrenoceptor-specific autoantibodies exert their receptor-mediated antiapoptotic effects on cardiomyocytes by shifting endogenous β1-adrenoceptors into the agonist-coupled high-affinity state (49). The high-affinity conformational changes signify tight coupling of β1-adrenoceptors to G protein and subsequent activation of post-receptor signal transduction pathways, which in excess leads to myocyte apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction (50). In a separate study, Staudt et al. (51) showed that the Fcγ receptor IIa (CD32a) might play an important role in the negative cardiac inotropic effect of IgG obtained from plasma of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. They provided evidence that suggests full expression of the negative inotropic effects of patient IgG in isolated cardiomyocytes requires not only the binding of autoantibodies to their respective cardiac epitopes via their Fab fragments, but also activation of myocyte Fcγ receptors IIa on cardiomyocytes via their Fc fragments. Unlike the intact patient IgG, the F(ab')2 fragments alone produced no functional effects in the isolated cardiomyocytes. Pretreatment with the F(ab')2 fragments also rendered the cardiomyocytes unresponsive to subsequent exposure to intact patient IgG, suggesting binding of the IgG to the cardiac antigen is essential for the effects of IgG. To study whether the cardiac effects of rabbit ß1-ECII IgG require its Fc fragments, we obtained purified Fab fragments from ß1-ECII IgG using the immobilized papain and protein A spin column of the Fab Preparation Kit (Pierce Biotechnology), which removes Fc and undigested IgG. Our preliminary experiments showed that unlike intact ß1-ECII IgG, its Fab fragments did not increase the protein expression of p-p38 MAPK, CHOP or cleaved caspase-12. Our findings support the functional importance of the Fc fragments in the mediation of the biological effect of ß1-ECII IgG, but additional experiments are needed to fully explore the roles of Fcγ receptors in autoimmune cardiomyopathy (52).

In summary, we have shown that adoptive passive transfer of β1-ECII IgG from rabbit autoimmune cardiomyopathy produces early cardiomyopathy and myocyte apoptosis in severe combined immunodeficiency mice. These effects are associated with the increased phosphorylation of CaMKII and p38 MAPK, and activation of the UPR and EOR responses in the ER. Evidence is also presented that the effects of β1-ECII IgG are mediated via the β1-adrenergic receptors, and that activation of the ER-resident caspase-12 is an important downstream mechanism for the β1-ECII IgG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Our findings provide novel mechanistic insight into pathophysiology of autoimmune cardiomyopathy, and potential new therapeutic interventions for dilated cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by the Public Health Service National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-68151, and the K and J Liang Charitable Gift Fund.

All authors declare no relationship that may be perceived as an actual or possible conflict of interest with the content of the manuscript.

The authors thank Ms. Robin Stuart-Buttles and Ms. Megan Simeone for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jahns R, Boivin V, Siegmund C, Inselmann G, Lohse MJ, Boege F. Autoantibodies activating human β1-adrenergic receptors are associated with reduced cardiac function in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:649–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwata M, Yoshikawa T, Baba A, Anzai T, Mitamura H, Ogawa S. Autoantibodies against the second extracellular loop of beta1-adrenergic receptors predict ventricular tachycardia and sudden death in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:418–24. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahns R, Boivin V, Lohse MJ. β1-adrenergic receptor function, autoimmunity, and pathogenesis of dilated cardiomyopathy. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallukat G, Wollenberger A, Morwinski R, Pitschner HF. Anti-β1-adrenoceptor autoantibodies with chronotropic activity from the serum of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: mapping of epitopes in the first and second extracellular loops. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:397–406. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staudt A, Mobini R, Fu M, Große Y, Stangl V, Stangl K, et al. β1-adrenoceptor antibodies induce positive inotropic response in isolated cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;423:115–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staudt Y, Mobini R, Fu M, Felix SB, Kühn JP, Staudt A. β1-adrenoceptor antibodies induce apoptosis in adult isolated cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;466:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsui S, Fu MLX, Katsuda S, Hayase M, Yamaguchi N, Teraoka K, et al. Peptides derived from cardiovascular G-protein-coupled receptors induce morphological cardiomyopathic changes in immunize rabbits. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:641–55. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwata M, Yoshikawa T, Baba A, Anzai T, Nakamura I, Wainai Y, et al. Autoimmunity against the second extracellular loop of β1-adrenergic receptors induces β-adrenergic receptor desensitization and myocardial hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res. 2001;88:578–86. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.6.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahns R, Boivin V, Hein L, Triebel S, Angermann CE, Ertl G, et al. Direct evidence for a β1-adrenergic receptor-directed autoimmune attack as a cause of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1419–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI20149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buvall L, Täng MS, Isic A, Andersson B, Fu M. Antibodies against the β1-adrenergic receptor induce progressive development of cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:1001–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui S, Larsson L, Hayase M, Katsuda S, Teraoka K, Kurihara T, et al. Specific removal of β1-adrenoceptor autoantibodies by immunoabsorption in rabbits with autoimmue cardiomyopathy improved cardiac structure and function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallukat G, Muller J, Hetzer R. Specific removal of β1-adrenergic antibodies from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1806. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200211283472220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, Oltz EM, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwimmbeck PL, Badorff C, Rohn G, Schulze K, Schultheiss P. Impairment of left ventricular function in combined immune deficiency mice after transfer of peripheral blood leukocytes from patients with myocarditis. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(Suppl 0):59–63. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/16.suppl_o.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omerovic E, Boliano E, Andersson B, Kujacic V, Schulze W, Hjalmarson A, et al. Induction of cardiomyopathy in severe combined immunodeficiency mice by transfer of lymphocytes from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Autoimmunity. 2000;32:271–80. doi: 10.3109/08916930008994101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsui S, Fu M, Hayase M, Katsuda S, Yamaguchi N, Teraoka K, et al. Transfer of rabbit autoimmune cardiomyopathy into severe combined immunodeficiency mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42(Suppl 1):S99–103. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200312001-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao W, Fukuoka S, Iwai C, Liu J, Sharma VL, Sheu SS, et al. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis in autoimmune cardiomyopathy: mediated via endoplasmic reticulum stress and exaggerated by norepinephrine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;0:01377.2006v1. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01377.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao W, Iwai C, Keng PC, Vulapalli R, Liang CS. Norepinephrine-induced oxidative stress causes PC-12 cell apoptosis by both endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial intrinsic pathway: inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase survival pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1373–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DH, Behke MA, Rose SD, Chang MS, Choi S, Rossi JJ. Synthetic dsRNA dicer substrates enhanced RNAi potency and efficacy. Nat Biotechnology. 2005;23:222–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoebeke J. Structural basis of antoimmunity against G protein-coupled membrane receptors. Int J Cardiol. 1996;54:103–11. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(96)02586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui S, Fu ML. prevention of experimental autoimmune cardiomyopathy in rabbits by receptor blockers. Autoimmunity. 2001;34:217–20. doi: 10.3109/08916930109007388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Communal C, Singh K, Pimentel DR, Colucci WS. Norepinephrine stimulates apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes by activation of the ß-adrenergic pathway. Circulation. 1998;98:1329–34. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.13.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu WZ, Wang SQ, Chakir K, Yang D, Zhang T, Brown JH, et al. Linkage of ß1-adrenergic stimulation to apoptotic heart cell death through protein kinase A-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II. J Clin Invest. 2003; 111:617–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI16326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, Zhu W, Wang S, Yang D, Crow MT, Xiao RP, et al. Sustained β1-adrenergic stimulation modulates cardiac contractility by Ca2+/Calmodulin kinase signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2004;95:798–806. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145361.50017.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lader AS, Xiao Y-F, Ishikawa Y, Cui Y, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, et al. Cardiac Gsα overexpression enhances L-type calcium channels through an adenylyl cyclase independent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engelhardt S, Hein L, Dyachenhow V, Kranias EG, Isenberg G, Lohse MJ. Altered calcium handling is critically involved in the cardiotoxic effects of chronic ß-adrenergic stimulation. Circulation. 2004;109:1154–60. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000117254.68497.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks AR. Calcium and the heart: a question of life and death. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:597–600. doi: 10.1172/JCI18067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berridge MJ. The endoplasmic reticulum: a multifunctional signaling organelle. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:235–49. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harding HP, Calfon M, Urano F, Novoa I, Ron D. Transcriptional and translational control in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18: 575–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.011402.160624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai E, Teodoro T, Volchuk A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Signaling the unfolded protein response. Physiology. 2007;22:193–201. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang S, Chow SC, Nicotera P, Orrenius S. Intracellular Ca2+ signals activate apoptosis in thymocytes: studies using the Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:84–92. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furuya Y, Lundmo P, Short AD, Gill DL, Isaacs JT. The role of calcium, pH, and cell proliferation in the programmed (apoptotic) death of androgen-independent prostatic cancer cells induced by thapsigargin. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6167–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman RJ. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1389–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI16886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo S, Lee AS. Requirement of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway for the induction of the 78kDa glucose-regulated protein/immunoglobulin heavy-chain binding protein by azetidine stress: activating transcription factor 6 as a target for stress-induced phosphorylation. Biochem J. 2002;366:787–95. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–4. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee AS. Mammalian Stress response: induction of the glucose regulated protein family. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992; 4:267–73. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90042-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2656–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, Batchvarova N, Lightfoot RT, Remotti H, et al. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–95. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1249–59. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA, et al. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-β. Nature. 2000;403:98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morishima N, Nakanishi K, Takenouchi H, Shibata T, Yasuhiko Y. An endoplasmic reticulum stress-specific caspase cascade in apoptosis. Cytochrome c-independent activation of caspse-9 by caspase-12. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34287–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao RV, Catro-Obreqon S, Frankowski H, Schuler M, Stoka V, del Rio G, et al. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. An apaf-1-independent intrinsic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21836–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadowaki H, Nishitoh H, Ichijo H. Survival and apoptosis signals in ER stress: the role of protein kinases. J Chem Neuroanat. 2004;28:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tobiume K, Matsuzawa A, Takahashi T, Nishitoh H, Morita K, Takeda K, et al. ASK1 is required for sustained activations of JNK/p38 MAP kinase and apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:222–8. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagai H, Noguchi T, Takeda K, Ichijo H. Pathophysiological roles of ASK1-MAP kinase signaling pathways. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;40:1–6. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2007.40.1.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Espada L, Udapudi B, Podlesniy P, Fabregat I, Espinet C, Tauler A. Apoptotic action of E2F1 requires glycogen synthase kinase 3-β activity in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2007;102:2020–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jahns R, Boivin V, Krapf T, Wallukat G, Boefe F, Lohse MJ. Modulation of beta1-adrrenoceptor activity by domain-specific antibodies and heart failure-associated autoantibodies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1280–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jane-wit D, Altuntas CZ, Johnson JM, Yong S, Wickley PJ, Clark P, Wang Q, Popović ZB, Penn MS, Damron DS, Perez DM, Tuohy VK. β1-Adrenergic receptor autoantibodies mediate dilated cardiomyopathy by agonistically inducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Circulation. 2007;116:399–410. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jahns R, Boivin V, Lohse MJ. Beta 1-adrnergic receptor-directed autoimmunity as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy in rats. Intern J Cardiol. 2006;112:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staudt A, Eichler P, Trimpert C, Felix SB, Greinacher A. Fcγ receptors IIa on cardiomyocytes and their potential functional relevance in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1684–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gupta S. Heartache of Fc receptors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1693–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]