Abstract

Capsaicinoids are botanical irritants present in chili peppers. Chili pepper extracts and capsaicinoids are common dietary constituents and important pharmaceutical agents. Use of these substances in modern consumer products and medicinal preparations occurs worldwide. Capsaicinoids are the principals of pepper spray self-defense weapons and several over-the-counter pain treatments as well as the active component of many dietary supplements. Capsaicinoids interact with the capsaicin receptor (a.k.a., VR1 or TRPV1) to produce acute pain and cough as well as long-term analgesia. Capsaicinoids are also toxic to many cells via TRPV1-dependent and independent mechanisms. Chemical modifications to capsaicinoids by P450 enzymes decreases their potency at TRPV1 and reduces the pharmacological and toxicological phenomena associated with TRPV1 stimulation. Metabolism of capsaicinoids by P450 enzymes also produces reactive electrophiles capable of modifying biological macromolecules. This review highlights data describing specific mechanisms by which P450 enzymes convert the capsaicinoids to novel products and explores the relationship between capsaicinoid metabolism and its effects on capsaicinoid pharmacology and toxicology.

CAPSAICINOID PHARMACOLOGY, TOXICOLOGY, AND HUMAN EXPOSURE SOURCES

The capsaicinoids are a family of natural products isolated from the fruits of “hot” peppers (Govindarajan, 1985; Govindarajan and Sathyanarayana, 1991). These substances produce the characteristic sensations associated with the ingestion of spicy food. Capsaicinoids elicit multiple characteristic pharmacological responses that include severe irritation, inflammation, erythema, and transient hyper- and hypoalgesia at exposed sites; capsaicinoids are particularly irritating to the eyes, skin, nose, tongue, and respiratory tract, where large numbers of sensory nerve fibers (C- and Aδ-) terminate that express high quantities of the capsaicin receptor (i.e., VR1 or TRPV1). TRPV1 has been cloned and its pharmacological properties and physiological roles characterized (Caterina et al., 1997). TRPV1 is a calcium channel that, when activated by capsaicinoids, produces the characteristic sensations previously described and causes toxicity in many mammalian cell types (Lee et al., 2000; Maccarrone et al., 2000; Macho et al., 2000; Surh, 2002; Reilly et al., 2003b; Agopyan et al., 2004; Reilly et al., 2005; Johansen et al., 2006). Several excellent and comprehensive reviews dedicated to TRPV1 have been published (Szallasi and Blumberg, 1999; Caterina and Julius, 2001).

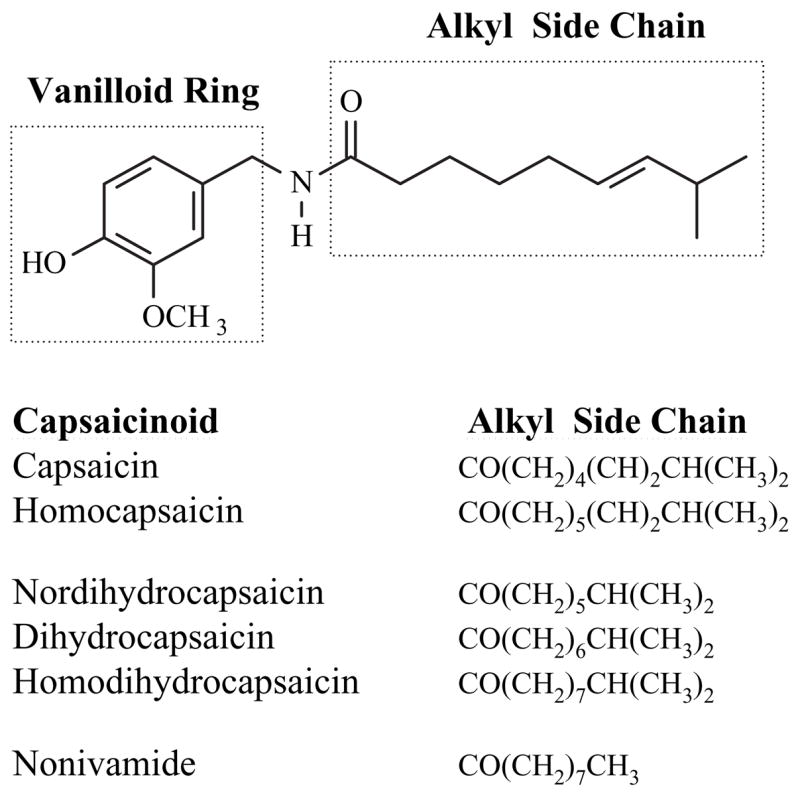

There are numerous naturally occurring capsaicinoid analogs (Kozukue et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005a; Thompson et al., 2005b), but six most abundant analogs are capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, nonivamide, homocapsaicin, and homodihydrocapsaicin (Reilly et al., 2001a; Reilly et al., 2001b). The chemical structures of the major capsaicinoid analogs are depicted in Fig. 1. All analogs have the capacity to bind to and activate TRPV1, albeit with different potencies depending primarily upon the alkyl chain structure (Pyman, 1925; Hayes, 1984; Gannett, 1990; Walpole et al., 1993a; Walpole et al., 1993b; Walpole et al., 1993c) and a 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzylamine (vanilloid) ring. Capsaicin and nonivamide are the most potent and pungent analogs, followed by dihydrocapsaicin and the remaining analogs. Common sources for human exposure to capsaicinoids include ingestion of spicy foods and use of oral dietary supplements; application of topical creams to treat chronic pain, neuralgia, and psoriasis; and inhalation by exposure to cooking fumes and pepper spray aerosols (Szallasi and Blumberg, 1993; Szallasi and Blumberg, 1999; Robbins, 2000; Reilly et al., 2001a; Reilly et al., 2001b; Szallasi and Appendino, 2004; Reilly, 2006). Capsaicinoids, in the form of oleoresin capsicum, are classified as GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) substances by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are approved as food additives or as topical analgesics without extensive toxicological profiling.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of capsaicin and related capsaicinoid analogs. The chemical structure of capsaicin is shown and the vanilloid ring and variable acyl termini potions of capsaicinoid analogs are highlighted. The structures of the alkyl termini of the major naturally occurring capsaicinoids are also represented in text form.

Early studies of capsaicinoid toxicity demonstrated extreme differences depending upon the route of exposure. Oral and topical capsaicin exposures yielded LD50 values in mice at 190 and 500 mg/kg, respectively, whereas intravenous and intratracheal instillation routes produced LD50 values of 0.56 and 1.6 mg/kg, respectively (Glinsukon et al., 1980). Regardless of the route of exposure, the cause of death for the animals was rapid onset of convulsions (within 0.05 [i.v.] to 3.38 [p.o.] minutes) due to cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction and failure. Routine use of capsaicinoid-containing products by humans in various forms on a daily basis by large numbers of diverse people suggest that capsaicinoids are safe under normal conditions via topical and oral routes. However, extreme exposure scenarios resulting in acute toxicity, severe injury, and fatality have occurred (Heck, 1995; Steffee et al., 1995; Billmire et al., 1996; Busker and van Helden, 1998; Smith and Stopford, 1999; Olajos and Salem, 2001; Granfield, 1994).

Excessive ingestion of oleoresin capsicum by a child undergoing homeopathic treatment of a digestive disorder resulted in death (Snyman, 2001). Severe cardiovascular and pulmonary toxicities have also been observed in subjects exposed to pepper sprays, particularly in those individuals who had pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular diseases or in individuals under the influence of illicit drugs (e.g., methamphetamine). The precise mechanisms by which the capsaicinoids precipitated these responses and the relationship, if any, between drug metabolism, activation of TRPV1, and pharmacological activity have been essentially unexplored.

Metabolism of Capsaicin by P450 Enzymes: Past and Present

Initial studies on the metabolism of capsaicin by P450 enzymes demonstrated the formation of multiple products arising from aromatic and alkyl hydroxylation (Lee, 1980; Kawada et al., 1984; Gannett, 1990; Surh et al., 1995; Surh and Lee, 1995). Because of the state and availability of modern sophisticated bioanalytical technologies at the time of these studies, typically, little definitive structural information for the observed metabolites was presented.

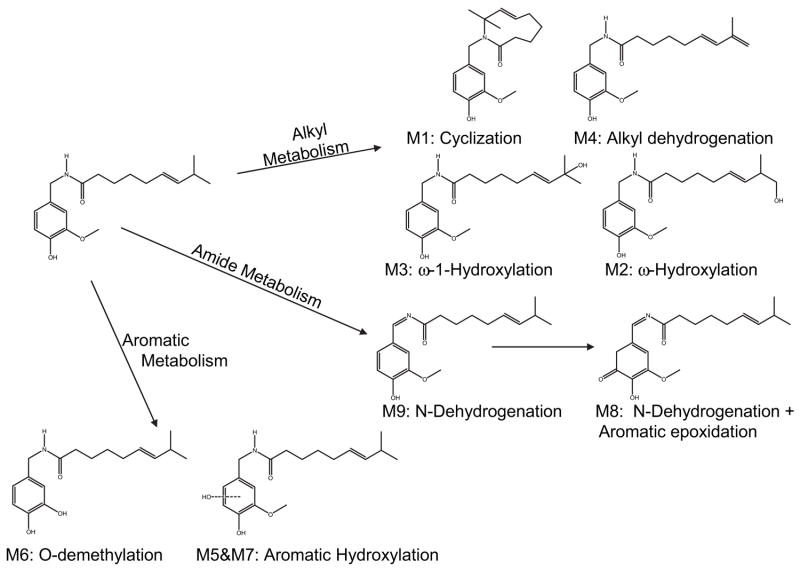

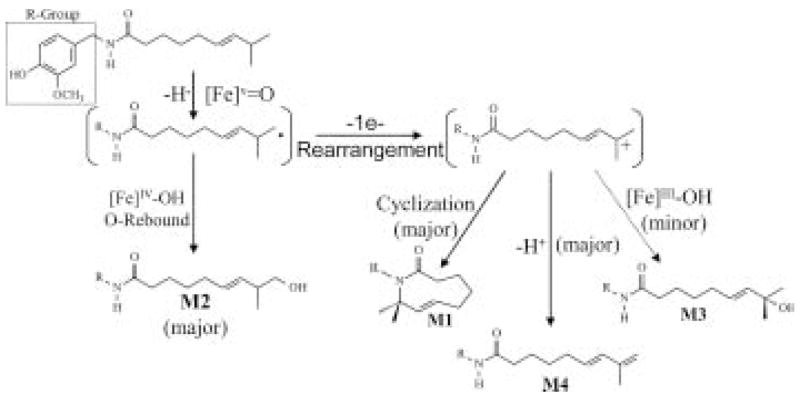

Recent studies performed in our laboratory have confirmed the initial conclusions regarding the formation of aliphatic and aromatic hydroxylated products. In addition, a number of new metabolites arising from multiple and novel metabolic processes were identified (Reilly et al., 2003a). Metabolites arising from alkyl dehydrogenation and oxygenation, aromatic hydroxylation, and O-demethylation were described. Based on extensive characterization of the metabolites by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS), UV-visible absorbance spectroscopy, and 1D- and 2D-proton and carbon-13 NMR, a scheme for the metabolism of capsaicin by human liver microsomal P450 enzymes was proposed (Fig. 2). Products included the formation of an unusual macrocyclic metabolite (M1) that was postulated to be formed through covalent bond formation between the amide nitrogen of capsaicin and a uniquely stable tertiary allylic carbocation at the penultimate (ω-1) carbon of the alkyl side-chain, a dehydroge-nated alkyl diene (M4), and a dehydrogenated imide metabolite (M9). The formation of ω-, and ω-1 alcohols (M2 and M3, respectively), two aromatic phenols (M5 and M7), and an O-demethylated metabolite (M6) was also observed. Tentative structural identification for a metabolite that was formed by N-dehydrogenation and subsequent aromatic hydroxylation (M8) was also presented. M8 exhibited UV-visible absorption characteristics consistent with a molecule with extended conjugation. The proposed structure and a potential mechanism for the formation of M8 via sequential oxidation processes involving the imide M9 as the secondary substrate are presented in Fig. 3. The relative amounts of each metabolite were dependent on the P450 enzymes that were used, as presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the primary metabolites of capsaicin produced by P450 enzymes and the associated metabolic pathways underlying their formation. Each metabolite has been given a reference number (M1–M9), which is used throughout the review. Specific details on the characterization of these metabolites and methods used to determine their structures can be found in Reilly et al. (2003a).

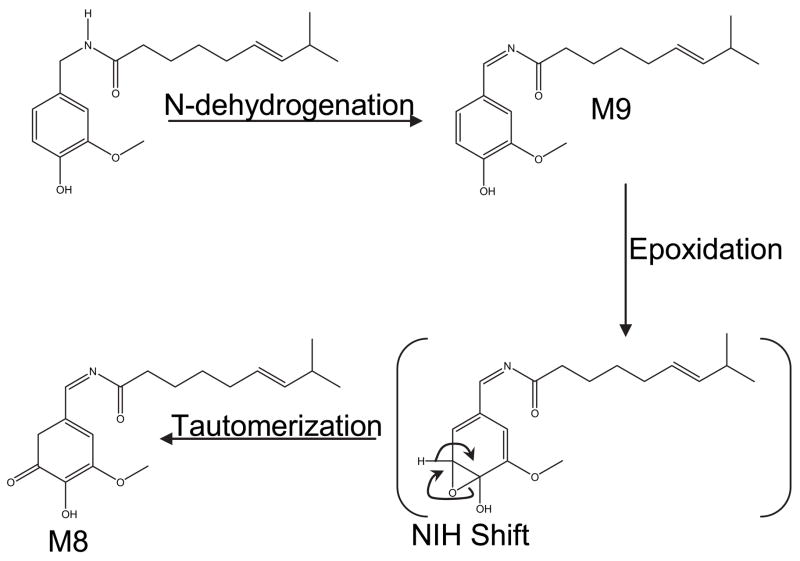

Figure 3.

Proposed metabolic pathway for the formation of M8 from M9 via a sequential P450-dependent oxidation process. Capsaicin is initially metabolized to generate an imide (M9), which subsequently undergoes epoxidation and tautamerization to generate M8 (Reilly et al., 2003a; Sun, 2006).

Table 1.

Relative metabolite abundance (pooled human liver microsomes) and the principal P450 enzymes responsible for producing each metabolite of capsaicin.

| Metabolite | Approx. % Total Metabolites (HLM) | Principal P450 Enzyme |

|---|---|---|

| M1 Macrocycle | 22 | 2C9, 2C19, 2E1 |

| M2 ω-OH | 26 | 2E1, 2C8 |

| M3 ω-1-OH | 6.5 | 3A4, 2C8 |

| M4 Diene | 26 | 2C9, 2C19, 2E1 |

| M5 Aromatic-OH | 1.3 | 1A2, 2C19 |

| M6 O-Demethyl | 5 | 1A2, 2C19, 3A4, 2D6 |

| M7 Aromatic-OH | 7.5 | 2B6, 2C8, 2E1 |

| M8 Oxygenated and Dehydrogenated | 2.9 | 3A4, 1A1, 2E1, 2C8, 2D6, 2B6 |

| M9 Imide | 2.6 | 3A4, 1A1, 2B6 |

Detoxification and Bioactivation of Capsaicin by P450s

Structure activity studies employing models of acute pain and altered pain sensitivity in mice have demonstrated a strict structural requirement for both the vanilloid ring pharmacophore and a hydrophobic alkyl side-chain consisting of 8–12 carbon atoms that may be saturated or unsaturated and branched or unbranched to have maximum potency at TRPV1 (Walpole et al., 1993b; Walpole et al., 1993a; Walpole et al., 1993c). Modifications to either of the pharmacophores of capsaicin, or its analogs, were shown to reduce potency drastically. Based on these data and studies of the proposed capsaicin-binding site of TRPV1 (Jordt and Julius, 2002; Gavva et al., 2004), one would predict that P450-dependent metabolism of capsaicinoids to produce the metabolites shown in Fig. 2 would limit the pharmacological and toxicological effects of these molecules via reduction in their affinity for TRPV1.

However, early research exploring the relationship between metabolism of capsaicinoids and capsaicinoid toxicity yielded conflicting results. Some studies have demonstrated that bioactivation of capsaicinoids by S9 liver fractions produced metabolites capable of inducing genetic mutations in the form of His+ reversions (Salmonella. typhimurium strains TA98, TA100, TA1535), azaguanine resistance in Chinese hamster V79 cells, micronuclei formation in Swiss and albino mice, and chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes (Surh and Lee, 1995). Proposed mechanisms for the mutagenicity of capsaicinoids involved the formation of an electrophilic epoxide, 1-electron oxidized phenoxyl radical intermediates (as observed for peroxidase-mediated metabolism of capsaicinoids), and/or redoxcycling of catechol/quinone metabolites arising from aromatic hydroxylation and/or O-demethylation. Unfortunately, definitive evidence for the formation of these metabolites by S9 fractions and detailed mechanistic toxicity studies were not performed. Furthermore, subsequent experiments to validate the mutagenicity findings failed to repeat the initial results completely (Lawson and Gannett, 1989).

Additional studies investigating the formation of electrophiles from capsaicin by P450 enzymes provided more direct evidence for the formation of metabolites capable of modifying biological macromolecules (Miller, 1983; Gannett, 1990). The authors of these studies proposed that the ability of radiolabeled capsaicinoids to bind microsomal proteins, including CYP2E1 and possibly other P450 enzymes, occurred through an electrophilic arene oxide or quinone methide. The latter metabolite is a common type of metabolite generated from structurally similar O-methoxy-4-alkylphenols (Thompson et al., 1995). Unfortunately, neither the formation of the epoxide nor the quinone methide was clearly demonstrated. With the discovery of TRPV1 in 1997, research on the relationship between capsaicinoid toxicity, pharmacology, and metabolism has gained new momentum and a number of detailed studies have demonstrated a direct relationship between the metabolic transformation of capsaicinoids and the role of the TRPV1 in capsaicinoid pharmacology and toxicity.

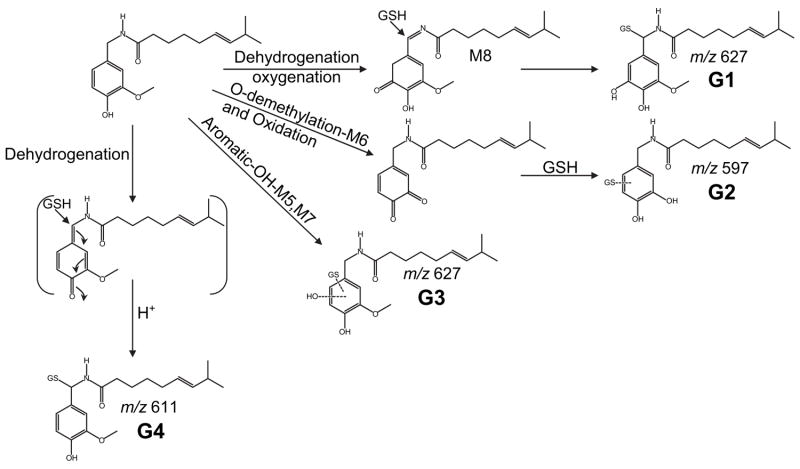

Recent studies in our laboratory of capsaicin metabolism by P450 enzymes has confirmed many of the hypotheses presented by earlier reports regarding electrophile formation. It has been demonstrated that at least four separate electrophilic metabolites are produced from capsaicin by P450 enzymes. Addition of the endogenous nucleophile glutathione (GSH) to in vitro metabolic incubations of capsaicin and human liver microsomes revealed that the O-demethylated (M6), the aromatic hydroxylated (M5 and M7), and the oxygenated imide metabolite M8 were amenable to depletion by GSH, whereas many other metabolites (e.g., M1, M2, and M3) were produced at significantly higher quantities. Corresponding GSH adducts of three of these metabolites have been identified by LC/MS/ MS (Fig. 4; G1–G3). In addition, evidence for the formation of a quinone methide metabolite, generated from P450-mediated oxidation of the 4-OH group of the vanilloid ring, has been obtained. This adduct (G4) exhibited properties consistent with addition of GSH to the benzylic position of the quinone methide metabolite, as would be predicted based on prior studies of related alkyl phenols and catechols (Iverson et al., 1995). All GSH adducts were identified using LC/MS/MS and neutral loss scanning of pyroglutamate (−129 u) and scanning for the loss of GSH (−307 u) from precursor ions (Baillie, 1993). A general scheme for the formation of electrophilic metabolites and GSH adducts of capsaicin by P450 enzymes is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Representative metabolic pathways that lead to the formation of glutathione adducts of capsaicin. Specific metabolic processes and resulting metabolites that are amenable to trapping by glutathione are shown. The corresponding [MH]+ ion for each adduct is also provided. Identification and preliminary structural assignments were generated by interpretation of liquid-chromatographic-tandem mass spectrometric data and comparison to predicted mass spectra (Mass Frontier 4.0).

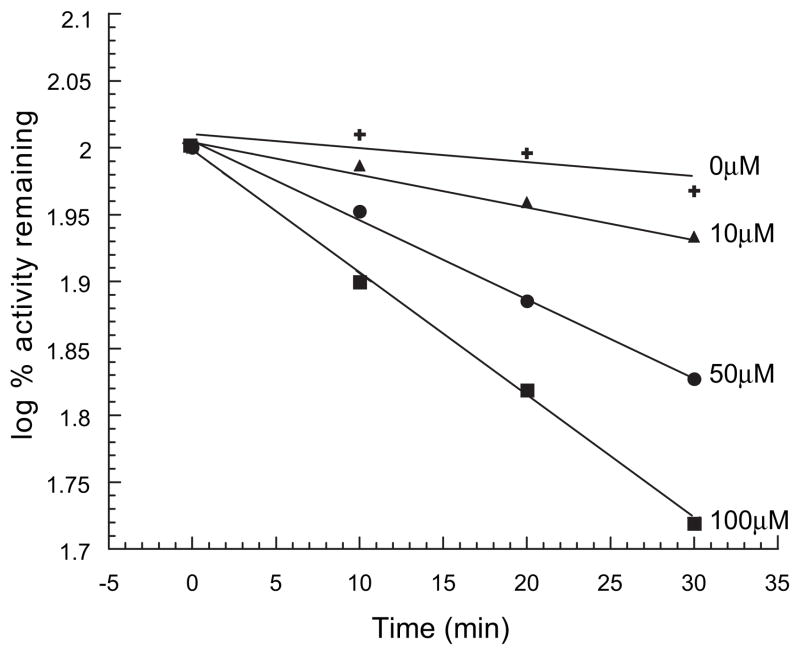

Unpublished studies from our laboratory have also demonstrated significance for P450 metabolism with respect to toxicity via the formation of electrophilic species from capsaicinoids. One or more of these reactive metabolites has been shown to cause the time, concentration, and NADPH-dependent inactivation of CYP2E1 (Fig. 5), as previously described (Miller, 1983; Gannett, 1990; Miller et al., 1993). Although not specifically tested, the inactivation of CYP2E1, and possibly other P450 enzymes, by capsaicinoids may have the potential to cause toxicities through a variety of mechanisms, including deleterious drug-drug interactions arising from deficiencies in drug clearance capacity. Alternatively, inhibition of P450 enzymes such as CYP2E1may prove to be beneficial, such as that shown for bioactivation of known pro-carcinogens that are bio-activated by P450 enzymes (Miller et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 1997; Tanaka, 2002).

Figure 5.

Time- and concentration-dependent inactivation of recombinant CYP2E1 by capsaicin. Incubations contained CYP2E1, NADPH, and various concentrations of capsaicin. At various time points after the addition of NADPH, aliquots were removed from the primary incubation mixture and assayed for residual p-nitrophenol (PNP) oxidase activity. Data are expressed as Log% remaining activity versus samples with no pre-incubation. Additional studies yielded the following criteria for inactivation: rate of inactivation = 0.02 min1, apparent KI = 25 μM, and a partition ratio = 7 (Smeal, 2002).

Preliminary studies from our laboratory also suggest that metabolism of capsaicinoids by P450s can alter toxicity. Assessment of capsaicinoid toxicity through activation of TRPV1 in a lung cell model was used to assess this process. The results demonstrated a decrease in toxicity when cells were treated with extracts of capsaicin metabolites extracated from in vitro incubations containing human liver microsomes with and without NADPH or added P450 (Table 2). Complimentary studies demonstrated an increase in toxicity with inhibition of P450-dependent metabolism in these cells with 1-aminmoben- zotriazole (1-ABT) (Table 2). Results demonstrating identical LD50 values for the O-demethylated metabolite (M6) in normal and TRPV1-overexpressing cells (Table 2) implied a non-TRPV1-dependent mechanism of toxicity. This alternate mechanism likely involved redoxcycling of the catechol with oxygen to form electrophilic quinoid metabolites and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Either of these products could then alter critical biomolecules and associuated cellular processes to promote toxicity. Hence, metabolism of capsaicinoids by P450 enzymes may play a dual role in capsaicioid toxicity and pharmacology. These studies provide support for the prior work on capsaicinoid toxicity and provide significant new data that illustrate the complex interactions between these metabolites and mechanisms of capsaicinoid bioactivity.

Table 2.

Approximate LD50 values for capsaicin in various cell lines treated with P450 inhibitors and P450- derived metabolites.

| Treatment | BEAS-2B | TRPV1-Over- expressing BEAS-2B | HepG2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | 100 ± 8 μM | 1 ± 0.3 μM | >200 μM |

| +0.5 mM 1-ABT | 90 ± 6 μM | Not Determined | 180 ± 8 μM |

| Extracted capsaicin | Not Determined | ~4 μM | Not Determined |

| Extracted capsaicin metabolites (HLM) | Not Determined | >10 μM | Not Determined |

| M6 (synthetic) | 5 ± 1 μM | 5 ± 2 μM | Not Determined |

Alkyl Dehydrogenation and Oxygenation of Capsaicinoids by P450 Enzymes

P450 enzymes are notorius for catalyzing the hydroxylation (oxygenation) of substrates. This process occurs via a well-defined series of chemical reactions involving the sequential transfer of electrons and protons between the P450 heme, substrate, and molecular oxygen. During substrate oxygenation reactions, P450 enzymes catalyze the site-specific abstraction of hydrogen from the substrate to generate intermediate substrate radicals that subsequently undergo oxygen rebound to form the corresponding hydroxylated product. The overall reaction can be summarized by the following equations, where R represents the substrate:

| (1) |

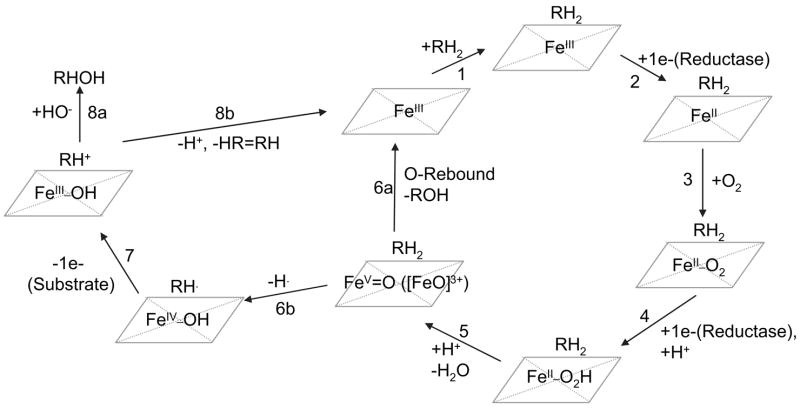

This catalytic process has been extensively characterized and is widely accepted. Many comprehensive reviews dedicated to this subject are available (Lewis and Pratt, 1998; Guengerich, 2001a; Guengerich, 2001b; Parkinson, 2001). This catalytic cycle is also depicted in Fig. 6, steps 1–6a.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the P450 catalytic cycle and specific features that dictate substrate hydroxylation and dehydrogenation. Each step is numbered and described in the text.

A less common and frequently overlooked pathway for xenobiotic metabolism by P450 enzymes involves the desaturation/dehydrogenation of chemicals to produce oxidized products, including alkenes. Numerous examples of substrate dehydrogenation reactions exist in the literature, including the formation of alkenes from fatty acids (Guan et al., 1998; Haining et al., 1999), a toxic alkene of valproic acid (Rettie et al., 1987; Rettie et al., 1988; Kassahun and Abbott, 1993; Rettie et al., 1995; Sadeque et al., 1997), ezlopitant (Obach, 2001), and reactive eneimine metabolites of the leukotriene receptor antagonist zafirlukast (Kassahun et al., 2005) and of the pneumotoxicant 3-methylindole (Adams et al., 1987; Yost, 1989; Ruangyuttikarn et al., 1991; Skiles and Yost, 1996; Skordos et al., 1998a; Skordos et al., 1998b; Loneragan et al., 2001). Interestingly, many dehydrogenated products of xenobiotics exhibit unique toxicity that is not observed for hydroxylated products.

Mechanistically, there are a number of similarities between substrate hydroxylation and dehydrogenation reactions, but distinct differences exist. Dehydrogenation of a substrate is electronically equivalent to substrate hydroxylation, with the exception that water does not balance the stoichiometry (Guengerich, 2001a). The dehydration process follows identical pathways as those previously described for hydroxylation. However, these pathways diverge, and a distinct feature of the desaturation process is the subsequent reduction of the ironoxo heme to form a substrate carbocation intermediate (Fig. 6, steps 6b and 7), which ultimately surrenders an additional proton to P450 to form a dehydrogenated product (Fig. 6, step 8b). This final step does not occur during the hydroxylation of substrates, which typically proceed by direct oxygen rebound with the intermediate substrate radical or by addition of a hydroxide equivalent to the carbocation intermediate. Because both hydroxylation and dehydrogenation of substrates occur via a similar catalytic process, the formation of these metabolites from a substrate typically coincides. However, in some instances, steric or substrate structural features unique to the enzyme and substrate pair skew the relative rates of the competing oxygen rebound and secondary hydrogen abstraction processes to increase or decrease the relative amounts of product formed. This aspect of P450 cataysis will be discussed in greater detail since this phenomenon appears to be a prominent feature of capsaicin metabolism by certain P450 enzymes. A schematic representation summarizing the biochemical processes that result in the formation of dehydrogenated and hydroxylated metabolites of xenobiotics by P450 enzymes is presented in Fig. 6.

As previously described, the initial characterization of metabolites produced from capsaicin by P450s revealed the formation of several alkyl dehydrogenated and hydroxylated metabolites (M1–M4). It was noted in these initial studies that there was a significant difference between the types and relative amounts of alkyl-derived metabolites generated from capsaicin and its unsaturated straight-chain analog nonivamide (Reilly and Yost, 2005). Specifically, the relative amounts of corresponding macrocyclic, ω-1-hydroxylated, alkene metabolites of nonivamide were much lower (some were not produced at all) than those of capsaicin. These preliminary results elicited a number of questions regarding the underlying chemical and biochemical processes and the criteria that dictated the formation of these metabolites from each substrate. These questions were addressed by a series of experiments that compared the alky metabolism of multiple natural and synthetic capsaicinoid analogs having variable alkyl terminal structure and were used to construct models describing the alkyl metabolism of capsaicinoids by P450 enzymes.

The effects of alkyl chain structure on the production of various metabolites from capsaicin and its analogs are described in detail in Reilly and Yost (2005). These capsaici-noid analogs used in this study varied in the degree of saturation at the ω-2,3 position, the presence or absence of a branched carbon chain at the ω-1 carbon, and altered alkyl chain length. The structures are shown in Fig. 1, with the exception of n-vanillyloctanamide and n-vanillyldecanamide, which differed from nonivamide (n-vanillylnonanamide) by −1 and +1 carbon in the alkyl chain, respectively. Results for the production of alkyl hydroxylated and dehydrogenated metabolites (M1–M4) from these variable substrates by human liver microsomes are summarized in Table 3. In general, the following trends were observed. Formation of macrocyclic, ω-1-hydroxylated, and diene/alkene metabolites was strictly dependent upon the configuration of the alkyl terminal structure. Specifically, substrates with a tertiary carbon atom and an unsaturated bond at the ω-2,3 position (capsaicin and homocapsaicin) exhibited the greatest propensity to form M1, M3, and M4, but substrates lacking the unsaturated bond at the ω-2,3 position (e.g., nordihydrocapsaicin, dihydrocap-saicin, and homodihydrocapsaicin) or straight-chain analogs (e.g., nonivamide and other n-acylvanillamides) produced markedly lower to nondetectable quantities of these metab-olites, respectively. These data were consistent with the concept that the relative free energy and stability of the radical and carbocation intermediates formed at the tertiary allylic carbon atom of capsaicin were much lower than those associated with formation of primary, secondary, or tertiary intermediates from straight-chain or saturated branched-chain analogs. The exceptional stability of the tertiary allylic intermediates formed with capsaicin ultimately dictated the formation of the macrocyclic (M1), diene (M4), and ω-1-hydroxylated (M3) metabolites from these diverse substrates. Decreases in the formation of M1, M3, and M4 from the other capsaicinoids paralleled the predicted stability and relative free energies associated with these molecules and supported the mechanism shown in Fig. 7. As represented graphically in Fig. 7, rearrangement of a primary terminal methyl radical intermediate is proposed to describe the product profiles observed and occurs prior to rearrangement to yield tertiary allylic intermediates and M1, M3, and M4. It is likely that a formal “primary” radical or carbocation intermediate did not form during metabolism by P450s. Rather, a transition state wherein the radical character was initially produced and primarily localized at the terminal position resulted in the formation of the terminal alcohol via rapid oxygen rebound processes. Subsequently, with some substrates in which the transition state charge density could be delocalized to more stable positions with lower free energy, rearrangement to ω-1 position and formation of a carbocation occurred and ultimately produced M1, M3, and M4 via intramolecular trapping, hydroxide addition, and loss of a second proton, respectively. As such, it was concluded that formation of radical and carbocation intermediates that can be stabilized and rearranged to more stable positions on the capsaicinoid molecule (e.g., the tertiary allylic position of capsaicin) would produce greater quantities of products attributed to formation of the metabolic intermediate at the ω-1 carbon. Conversely, substrates that lack the tertiary allylic motif do not exhibit large favorable changes in free energy upon rearrangement of the terminal methyl radical to the ω-1 position, and would only form products derived from metabolism of the alkyl terminal carbon atom (i.e., M2).

Table 3.

Relative production of alkyl-derived metabolites of multiple capsaicinoid analogs with different alkyl terminal structure by pooled human liver microsomes.

| Capsaicinoid Analog | Relative Metabolite Production Versus Capsaicin (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated analogs | Macrocycle | ω-OH | ω-1-OH | Terminal Alkene |

| Nordihydrocapsaicin | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 90 ± 14 | N.D. | 15 ± 4 |

| Dihydrocapsaicin | 6 ± 2 | 180 ± 15 | N.D. | 23 ± 9 |

| Homodihydrocapsaicin | 10 ± 2 | 193 ± 7 | N.D. | 29 ± 6 |

| Straight-chain analogs | Macrocycle | ω-OH | ω-1-OH | Terminal Alkene |

| n-Vanillyloctanamide | N.D. | 54 ± 5 | N.D. | 3 ± 1 |

| Nonivamide | N.D. | 135 ± 8 | N.D. | 6 ± 3 |

| n-Vanillyldecanamide | N.D. | 170 ± 15 | N.D. | 14 ± 5 |

| Increased chain lengths | Macrocycle | ω-OH | ω-1-OH | Diene |

| Homocapsaicin | 48 ± 8 | 50 ± 13 | 60 ± 12 | 8 ± 1 |

Figure 7.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the metabolism of capsaicin by P450 enzymes to generate the alkyl-derived metabolites M1, M2, M3, and M4. Capsaicin is initially activated at the alkyl terminus to generate an unstable terminal methyl radical. This species rapidly undergoes oxygen rebound to yield M2, a primary product of all capsaicinoids. Alternatively, this unstable intermediate can rearrange and surrender an additional electron to the high-valent iron oxygen heme complex of the enzymes to yield a carbocation intermediate at the ω-1 carbon atom. This process primarily occurs for capsaicinoids with a tertiary allylic carbon atom where the carbocation is highly stabilized. Little to no rearrangement products are observed for capsaicinoids having a tertiary or secondary carbon only. Formation of the tertiary allylic carbocation is requisite for the formation of significant quantities of M1, M3, and M4. Additional details for these mechanisms are presented in Reilly and Yost (2005).

The exclusive formation of ω-hydroxylated metabolites from many of the capsaicinoid analogs supported the mechanism presented in Fig. 7. In general, metabolism of all capsaicinoid analogs resulted in the formation of large quantities of ωl-hydroxylated (M2) metabolites, essentially independent of alkyl terminal structure. One interpretation of these data suggests a catalytic mechanism that involves the initial abstraction of hydrogen from the terminal carbon atom by the ironoxo heme prosthetic group of P450 enzymes, as shown in Fig. 7. However, based on the relative activation energies associated with abstraction of hydrogen from either the ω- or ω-1 carbon atom and the relative stability of the resulting radical intermediate, one would predict that products derived from formation of a metabolic intermediate at the omega;-1 carbon atom (e.g., M1, M3, or M4) would dominate the product profiles. This trend has been shown for a number of lipids and substrates sharing structural similarity to capsaicin and its straight-chain analogs (Rettie et al., 1987; Rettie et al., 1988; Kassahun and Abbott, 1993; Rettie et al., 1995; Sadeque et al., 1997; Adas et al., 1998; Bylund et al., 1998a; Bylund et al., 1998b; Guan et al., 1998; Adas et al., 1999; Haining et al., 1999; Chuang et al., 2003), but it was not observed for the capsaicinoid analogs. These data suggest that, not only do the chemical structure of the alkyl terminus of the capsaicinoids and the propensity to form stable rearrangement products dictate the types of metabolites that are formed, but specific enzyme substrate interactions unique to capsaicinoids in many P450 enzymes also contribute to metabolic fate. Hence, certain features of the capsaicinoids likely restrict access of the omega;1 carbon to the P450 heme, thus favoring initial substrate activation at the terminal carbon atom. In such a scenario, the unusual obligate abstraction of hydrogen from the terminal methyl position of capsaicinoids would occur, as previously discussed, and products derived from formation of a radical or carbocation intermediate at the omega;-1 position would form indirectly. This scenario appears to be the case for capsaicinoids.

Enzyme Substrate Interactions that Govern Capsaicinoid Metabolism

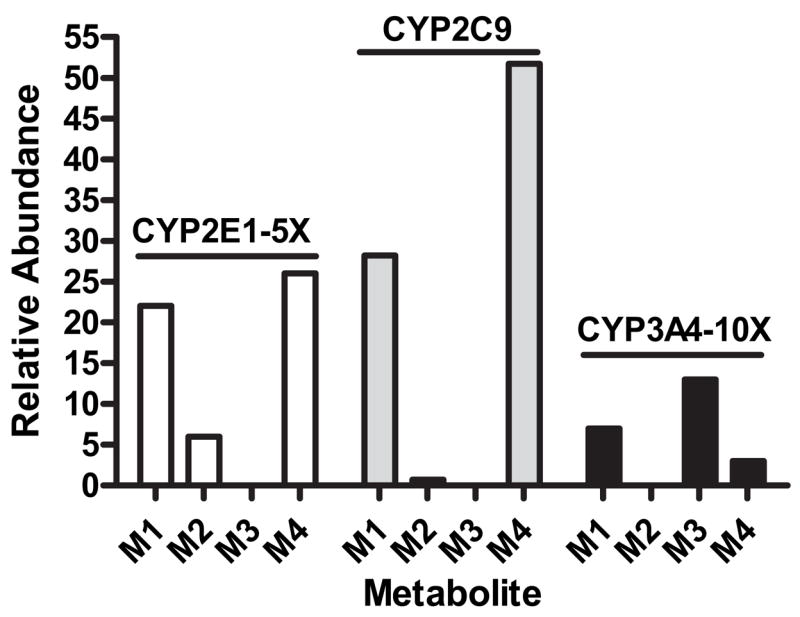

Unique metabolite profiles are observed when using individual recombinant P450 enzymes (Reilly and Yost, 2005). The most explicit examples of this phenomenon are the near exclusive formation of the alkyl dehydrogenated products (M1 and M4) by CYP2C9; the preferential production of the omega;-hydroxylated metabolite (M2) and M1 and M4 by CYP2E1; and the formation of only alkyl-derived metabolites arising from formation of metabolic intermediates at the omega;-1 carbon atom (M1, M3, and M4) by CYP3A4 (Fig. 8). The metabolite profile observed for CYP3A4 represents what would be predicted based on thermodynamic/energetic principles that typically govern the metabolism of lipids and other substrates and are consistent with published data for the P450-dependent metabolism of other alkanes shown to undergo activation preferentially at the omega;-1 positions (Adas et al., 1998; Bylund et al., 1998a; Bylund et al., 1998b; Guan et al., 1998; Adas et al., 1999; Haining et al., 1999; Chuang et al., 2003). As such, CYP3A4 appears to demonstrate a lack of steric restriction for substrate access to the P450 heme, whereas CYP2C9 and CYP2E1 demonstrate unexpected metabolite profiles that strongly suggest that specific enzyme substrate interactions between capsaicin and these enzymes play a definitive role in determining both the types of reactions that can occur (i.e., partitioning between dehydrogenation vs. oxygenation reactions) and the specific site at which initial hydrogen abstraction occurs (i.e., omega;- vs. omega;-1). Detailed reviews describing the concept of orientation-directed dehydrogenation and hydroxylation reactions by P450s can be found in Meunier et al. (2004) and Kumar et al. (2004).

Figure 8.

Selective production of metabolites M1–M4 by CYP2E1, 2C9, and 3A4. Data represent the relative abundance (peak areas) of each metabolite obtained from the analysis of in vitro metabolic incubations by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using acquisition parameters specific for the detection of each metabolite (Reilly et al., 2003a; Reilly and Yost, 2005). All peak areas were normalized to that of an internal standard. For clarity, data for CYP2E1 are amplified by a factor of 5 and those for CYP3A4 by 10. Equal quantities of recombinant P450 enzymes were used.

To further address the concept of sterically directed reaction mechanisms and to address the hypothesis that specific interactions between P450 active site residues dictated substrate access to the P450 heme and associated metabolic mechanisms, the metabolism was evaluated for a series of nonivamide analogs having 1) altered alkyl chain length and 2) specific modifications to the vanilloid ring structure. It was found that increasing the alkyl chain length of the capsaicinoid increased the formation of omega;-alcohols (see Table 3). These data implied that one of two processes was operational: 1) the increased hydrophobicity of the substrate favored partitioning into the enzyme and/or 2) longer alkyl chain lengths allowed for the alkyl terminus to penetrate more freely into the active site of P450s such that interactions between the substrate terminus and the ironoxo heme became more favorable. Additional studies to elucidate this phenomenon will be required in order to understand fully the significance of these results. Specifically, the possibility will be investigated that even greater alkyl chain lengths (>10 carbon atoms) will promote metabolic switching to the omega;-1 position or that shorter lengths (<8 carbon atoms) will prevent terminal alcohol formation. These data would ultimately support the hypothesis that the vanilloid ring moiety of capsaicinoids dictates metabolism of the alkyl terminus of these molecules by P450 enzymes.

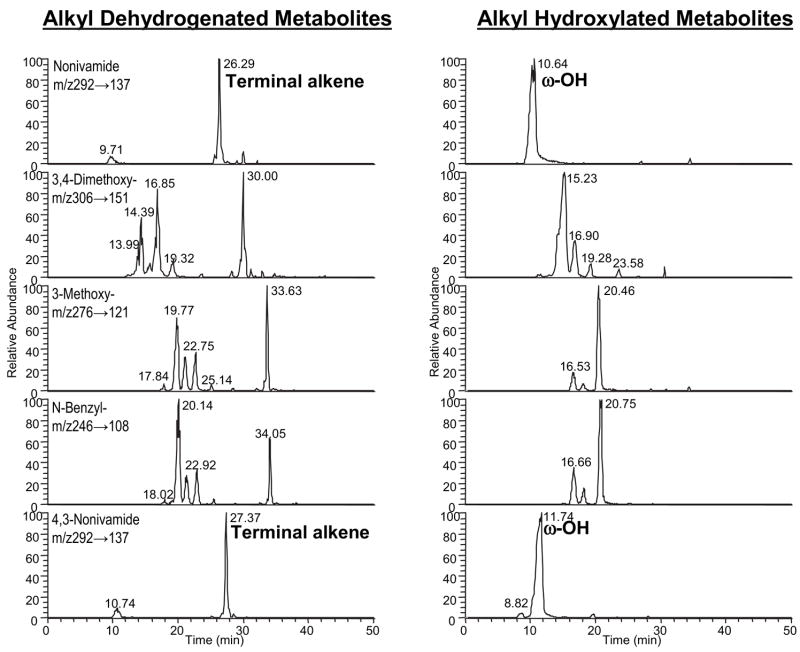

Additional studies using nonivamide analogs with altered vanilloid ring structures were also performed to address the previously stated hypothesis. Elimination or alkylation of the 4-OH group on the vanilloid ring of nonivamide, as in n-benzylnonanamide, 3,4-dimethoxy-n-benzylnonanamide, or 3-methoxy-n-benzylnonanamide, drastically altered the apparent ability of P450 enzymes to catalyze intra-chain oxidation and dehydrogenation reactions. For these three variant substrates, a number of metabolites were observed having MS/MS properties consistent with modifications to the alkyl chain at multiple positions along the chain. Fig. 9 depicts selected-reaction monitoring LC/MS/MS chromatograms showing metabolite peaks that exhibit precursor-to-product ion transitions specific to either addition of oxygen to the alkyl chain ([M + 16]+ →unchanged aromatic ring) or dehydrogenation of the alkyl chain ([M – 2]+→ged aromatic ring). The chromatograms show that essentially one product is formed from nonivamide but that multiple products are formed from the other analogs. Although the identities of these metabolites have not been confirmed, the preliminary LC/MS/MS data strongly support the conclusion that the 4-OH group of capsaicinoids controls binding in P450 enzymes and ultimately dictates alkyl metabolism. Ablation of specific interactions between the vanilloid ring -OH group and P450 active site residues allows for conformations that favor oxidation at multiple locations along the alkyl chain, as opposed to obligate metabolism of the alkyl terminus of nonivamide (or capsaicin). Additional support for this conclusion was obtained using a 4-methoxy-3-hydroxy-nonivamide analog. Changes in alkyl metabolism of this substrate were not observed relative to nonivamide, suggesting a hydroxyl group at either the 3- or 4-position on the vanilloid ring serves as a requisite hydrogen bond donors to direct terminal oxidation of the alkyl terminus of the capsaicinoid molecule. Hence, it is likely that, for many P450 enzymes, particularly those with relatively restricted active sites (e.g., CYP2E1 and CYP2C9), specific interactions between the 4-OH group on the vanilloid ring of capsaicinoids and key residues in the active sites of certain P450 enzymes control substrate binding in a way that prevents the intra-chain oxidation of the capsaicinoids.

Figure 9.

Representative liquid chromatographic-tandem mass spectrometric chromatograms from the analysis of alkyl-derived metabolites (M1–M4 and similar) produced by dehydrogenation (left panel) and hydroxylation (right panel) of structural variants of nonivamide. From top to bottom: Nonivamide (n-vanillylnonanamide), 3,4-dimethoxy-n-benzylnonanamide, 3-methoxy-n-benzylnonanamide, n-benzylnonanamide, and a 4-methoxy-3-hydroxy-nonivamide analog. Specific criteria for the analysis of these metabolites by tandem mass spectrometry are provided in the figures. Known metabolites of nonivamide are labeled. The series of peaks present for the nonivamide analogs exhibit chromatographic and mass spectrometric properties consistent with the formation of multiple metabolites derived from dehydrogenation and hydroxylation of the alkyl chain at multiple locations from the terminal carbon inward. These data are consistent with the elution profiles for such metabolites derived from capsaicin, suggesting that multiple metabolic sites occur on the alkyl side-chains of these nonivamide (vanilloid ring) variants.

An illustration of how the 4-OH group may restrict access of the alkyl chain to the ironoxo heme of CYP2C9 is shown in Fig. 10. This model represents one of several similar and energetically favorable poses that were predicted for capsaicin in CYP2C9. This model depicts an “end-on” orientation for capsaicin in the active site of CYP2C9, where the 4-OH group of the vanilloid ring is positioned near Glu104, Phe114, and Leu208, in a “pocket” distal to the heme iron. As a result, the alkyl terminus extends toward the heme iron and the ω- and ω-1 carbon atoms reside ~4.7 and ~5.12 Å away from the heme iron center, respectively. Analysis of space-filling renderings of this model suggest that substitution of the Phe114 with a more bulky residue, such as Trp, may potentially limit the three-dimensional space of the vanilloid ring binding “pocket.” Indeed, site-directed mutagenesis studies in which Phe114 of CYP2C9 was substituted with Trp demonstrated a shift in the relative ratio of M1 to M4 produced by the mutant enzyme. The ratio of M1/ M4 produced by the Phe114Trp mutant was ~2.7 versus ~0.5 for the wild-type enzyme. This marked change in distribution was attributable to an increase in the km for M4 formation from ~3 μM to ~ 40 μM with the mutant enzyme. Only minor changes were observed for M1 formation (km ~ 2 μM to 7 μM). These data imply that metabolism of capsaicin by CYP2C9 to produce M1 and M4 can be selectively altered by mutations that have the capacity to alter a predicted binding site for the vanilloid ring and that loss of a second proton to produce M4 was more favorable than intramolecular trapping of the tertiary allylic carbocation to form M1.

Figure 10.

Hypothetical docking models representing capsaicin bound in the active site of human CYP2C9. Energy minimized and high probability docking poses were generated in collaboration with Dr. Eric Johnson (The Scripps Research Institute). The pose on the left suggests an “end-on” motif where the terminal carbon atom of capsaicin is in close proximity to the P450 heme center. The alternative pose (right) places capsaicin in a “folded” confirmation with the alkyl terminus in close proximity to the P450 heme center with similar distances separating the amide nitrogen of capsaicin and the proposed site at which the stabilized intermediate carbocation forms. These representations, in combination with the data presented in the text, provide novel insights into the formation of M1–M4 by CYP2C9.

Another energetically favorable and predicted position places capsaicin in a “folded” conformation, where the alkyl terminus of capsaicin resides 5.3–5.4 Å from the heme iron center while the distance between the proposed metabolic tertiary allylic intermediate of capsaicin (that precedes M1 and M4 formation) and the amide nitrogen atom of capsaicin are separated by a mere 6.3 Å. Site-directed mutagenesis studies using single and double mutants of CYP2C9, ΔPhe476Trp-CYP2C9 and ΔPhe114Trp/ Phe476Trp-CYP2C9, demonstrated similar shifts in the relative ratio of M1 to M4 produced. Ratios of ~11.6 and 6.3 were observed for the two mutant enzymes, respectively. For the ΔPhe476Trp-CYP2C9 enzyme, an increase was observed in the km for M1 formation from ~2 μM to ~30 μM and a concomitant 6-fold increase in the Vmax for M1 formation and 5-fold decrease in M4 formation. One interpretation of these data is that substitution of Phe476 with Trp creates a new, lower affinity substrate binding site, whereby the “folded” conformation becomes favored and, thus, intramolecular trapping of the proposed tertiary allylic carbocation intermediate of capsaicin within the active site of CYP2C9 is facilitated. This idea may be particularly germane to the double mutant, where the possible binding location of the vanilloid ring in the “end-on” position is also restricted. Collectively, these studies provide mechanistic rationale to explain the differences between capsaicinoid metabolism on the alkyl chain versus that of other molecules.

CONCLUSIONS

This review highlights a number of interesting concepts about the biological fate of capsaicinoids and how metabolism by P450 enzymes contributes to both detoxification and bioactivation processes in humans. It was a goal of this review to provide new insights into critical aspects of P450-dependent metabolic processes that dictate substrate metabolism and to relate these processes to molecular mechanisms of xenobiotic toxicity. Although far from a complete story, the data discussed in this review present a number of new and intriguing findings that may be important for the interpretation of future studies involving the metabolism of structurally related chemicals by P450 enzymes. Furthermore, these data may serve as preliminary insights to support new avenues of research related to the pharmacological and toxicological properties of capsaicinoids in humans. Specifically, do polymorphisms or individual differences in phase 1 or phase II drug metabolizing enzyme expression profiles predispose certain types of cells, tissues, or individuals to infrequent but potentially significant idiosyncratic responses to capsaicin? It is well known that individual susceptibility to capsaicin can be highly variable. However, the mechanism remains unclear. Is this due to differences in metabolism where bioactivation to toxic intermediates that alter biological macromolecule function promotes reactivity? Alternatively, is erratic sensitivity the result of deficient (or excessive) clearance of these molecules such that more (or less) agent is available to activate TRPV1? Recent studies have described a potential benefit of capsaicinoids as chemotherapeutic agents to reduce certain types of cancer (e.g., prostate) (Mori, 2006). Meanwhile, others have shown that capsaicinoids may increase the risk of certain types of cancers (Toth and Gannett, 1992; Lopez-Carrillo et al., 1994; Archer and Jones, 2002). What, if any, is the role of drug metabolism in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention by capsaicinoids? Are differences in the metabolism of capsaicinoids responsible for these phenomena? These questions have only begun to be addressed by investigators, and it will be fascinating to learn what current studies will reveal in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge those who have contributed to the research described in this review: Ms. Stacy Smeal, Mr. Timothy Bolduc, Mr. Hao Sun, Dr. LaHoma Easterwood, Mr. Fred Henion, Ms. Diane Lanza, and the staff at the Center for Human Toxicology at the University of Utah. In addition, we acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Alan Rettie and Carrie Mosher (University of Washington), Dr. Eric Johnson (The Scripps Research Institute), Drs. William Ehlhardt and Palaniappan Kulanthaivel (Lilly Research Laboratories), and Dr. Abdul Mutlib (Pfizer). This work was supported by a contract from the Department of Commerce (60NANBOD0006) and the following NIH research grants: HL069813, HL13645, and GM074249.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BEAS-2B

immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells

- CYP

Cytochrome P450

- Glu

Glutamic acid

- GSH

Glutathione

- HepG2

human hepatoma cells

- i.v

intravenous dosage

- LC/MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- LD50

(lethal dose for 50% of the test population)

- Leu

Leucine

- NADPH

NADP+, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced and oxidized forms

- Phe

Phenylalanin

- p.o

oral dosage

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- S9

Supernatant fraction after centrifugation at 9000 × g for 30 minutes

- Trp

Tryptophan

- TRPV1

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid-1

- UV

Ultraviolet

- 1-ABT

1-Aminobenzotriazole

Footnotes

Presented at the Seventh International Symposium on Biological Reactive Intermediates, Tucson, Arizona, January 4–7, 2006.

References

- Adams JD, Heins MC, Yost GS. 3-Methylindole inhibits lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149:73, 78. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adas F, Berthou F, Picart D, Lozac’h P, Beauge F, Amet Y. Involvement of cytochrome P450 2E1 in the (omega-1)-hydroxylation of oleic acid in human and rat liver microsomes. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1210, 1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adas F, Berthou F, Salaun JP, Dreano Y, Amet Y. Interspecies variations in fatty acid hydroxylations involving cytochromes P450 2E1 and 4A. Toxicol Lett. 1999;110:43, 55. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agopyan N, Head J, Yu S, Simon SA. TRPV1 receptors mediate particulate matter-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L563–572. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00299.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer VE, Jones DW. Capsaicin pepper, cancer and ethnicity. Med Hypotheses. 2002;59:450–457. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(02)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie T, Davis MR. Mass spectrometry in the analysis of glutathione conjugates. Biol Mass Spec. 1993;22:319, 325. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billmire DF, Vinocur C, Ginda M, Robinson NB, Panitch H, Friss H, Rubenstein D, Wiley JF. Pepper-spray-induced respiratory failure treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatrics. 1996;98:961–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busker RW, van Helden HP. Toxicologic evaluation of pepper spray as a possible weapon for the Dutch police force: risk assessment and efficacy. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19:309, 316. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199812000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund J, Ericsson J, Oliw EH. Analysis of cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic and linoleic acids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with ion trap MS. Anal Biochem. 1998a;265:55–68. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund J, Kunz T, Valmsen K, Oliw EH. Cytochromes P450 with bisallylic hydroxylation activity on arachidonic and linoleic acids studied with human recombinant enzymes and with human and rat liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998b;284:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487, 517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, Helvig C, Taimi M, Ramshaw HA, Collop AH, Amad M, White JA, Petkovich M, Jones G, Korczak B. CYP2U1, a novel human thymus and brain specific cytochrome P450 catalyzes omega - and (omega -1)-hydroxylation of fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;279:6305–6314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannett P, Iversen P, Lawson T. The mechanism of inhibition of cytochrome P450IIE1 by dihydrocapsaicin. Biorg Chem. 1990;15:185, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Gavva NR, Klionsky L, Qu Y, Shi L, Tamir R, Edenson S, Zhang TJ, Viswanadhan VN, Toth A, Pearce LV, Vanderah TW, Porreca F, Blumberg PM, Lile J, Sun Y, Wild K, Louis JC, Treanor JJ. Molecular determinants of vanilloid sensitivity in TRPV1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20283, 20295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinsukon T, Stitmunnaithum V, Toskulkao C, Buranawuti T, Tangkrisanavinont V. Acute toxicity of capsaicin in several animal species. Toxicon. 1980;18:215, 220. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(80)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan VS. Capsicum production, technology, chemistry, and quality. Part 1: History, botany, cultivation, and primary processing. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1985;22:109, 176. doi: 10.1080/10408398509527412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan VS, Sathyanarayana MN. Capsicum–production, technology, chemistry, and quality. Part V. Impact on physiology, pharmacology, nutrition, and metabolism; structure, pungency, pain, and desensitization sequences. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1991;29:435, 474. doi: 10.1080/10408399109527536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfield J, Onnen J, Petty CS. Pepper spray in incustody deaths. NIJ/Science and Technology 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Guan X, Fisher MB, Lang DH, Zheng YM, Koop DR, Rettie AE. Cytochrome P450-dependent desaturation of lauric acid: isoform selectivity and mechanism of formation of 11-dodecenoic acid. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;110:103, 121. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(97)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP. Common and uncommon cytochrome p450 reactions related to metabolism and chemical toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001a;14:611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP. Uncommon P450-catalyzed reactions. Curr Drug Metab. 2001b;2:93–115. doi: 10.2174/1389200013338694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haining RL, Jones JP, Henne KR, Fisher MB, Koop DR, Trager WF, Rettie AE. Enzymatic determinants of the substrate specificity of CYP2C9: role of B’-C loop residues in providing the pi-stacking anchor site for warfarin binding. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3285–3292. doi: 10.1021/bi982161+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A, Oxford A, Reynolds M, Shingler AH, Skingle M, Smith C, Tyers MB. The effects of a series of capsaicin analogues on nociception and body temperature in the rat. Life Sci. 1984;34:1241, 1248. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck A. Accidental pepper spray discharge in an emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 1995;21:486. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson SL, Hu LQ, Vukomanovic V, Bolton JL. The influence of the p-alkyl substituent on the isomerization of o-quinones to p-quinone methides: potential bioactivation mechanism for catechols. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:537, 544. doi: 10.1021/tx00046a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen ME, Reilly CA, Yost GS. TRPV1 antagonists elevate cell surface populations of receptor protein and exacerbate TRPV1-mediated toxicities in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol Sci. 2006;89:278, 286. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ECS, Pyman FL. Relation between chemical composition and pungency in acid amides. J Am Chem Soc. 1925;127:2588, 2598. [Google Scholar]

- Jordt SE, Julius D. Molecular basis for species-specific sensitivity to “hot” chili peppers. Cell. 2002;108:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassahun K, Abbott F. In vivo formation of the thiol conjugates of reactive metabolites of 4-ene VPA and its analog 4-pentenoic acid. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:1098, 1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassahun K, Skordos K, McIntosh I, Slaughter D, Doss GA, Baillie TA, Yost GS. Zafirlukast metabolism by cytochrome P450 3A4 produces an electrophilic alpha,beta-unsaturated iminium species that results in the selective mechanism-based inactivation of the enzyme. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1427, 1437. doi: 10.1021/tx050092b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada T, Suzuki T, Takahashi M, Iwai K. Gastrointestinal absorption and metabolism of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984;72:449, 456. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozukue N, Han JS, Kozukue E, Lee SJ, Kim JA, Lee KR, Levin CE, Friedman M. Analysis of eight capsaicinoids in peppers and pepper-containing foods by high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:9172, 9181. doi: 10.1021/jf050469j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, De Visser SP, Shaik S. Oxygen economy of cytochrome P450: what is the origin of the mixed functionality as a dehydrogenase-oxidase enzyme compared with its normal function? J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5072–5073. doi: 10.1021/ja0318737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Gannett P. The mutagenicity of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in V79 cells. Cancer Lett. 1989;48:109, 113. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(89)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kumar S. Metabolism In Vitro of Capsaicin, A Pungent Principle of Red Pepper, With Rat Liver Microsomes. New York: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Nam DH, Kim JA. Induction of apoptosis by capsaicin in A172 human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;161:121, 130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DF, Pratt JM. The P450 catalytic cycle and oxygenation mechanism. Drug Metab Rev. 1998;30:739, 786. doi: 10.3109/03602539808996329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loneragan GH, Gould DH, Mason GL, Garry FB, Yost GS, Lanza DL, Miles DG, Hoffman BW, Mills LJ. Association of 3-methyleneindolenine, a toxic metabolite of 3-methylindole, with acute interstitial pneumonia in feedlot cattle. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:1525, 1530. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Carrillo L, Hernandez Avila M, Dubrow R. Chili pepper consumption and gastric cancer in Mexico: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:263, 271. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M, Lorenzon T, Bari M, Melino G, Finazzi-Agro A. Anandamide induces apoptosis in human cells via vanilloid receptors. Evidence for a protective role of cannabinoid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31938, 31945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho A, Lucena C, Calzado MA, Blanco M, Donnay I, Appendino G, Munoz E. Phorboid 20-homovanillates induce apoptosis through a VR1-independent mechanism. Chem Biol. 2000;7:483, 492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier B, de Visser SP, Shaik S. Mechanism of oxidation reactions catalyzed by cytochrome p450 enzymes. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3947, 3980. doi: 10.1021/cr020443g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CH, Zhang Z, Hamilton SM, Teel RW. Effects of capsaicin on liver microsomal metabolism of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK. Cancer Lett. 1993;75:45, 52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90206-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Brendel K, Burks TF, Sipes IG. Interaction of capsaicinoids with drug metabolizing systems. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:547, 551. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90537-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori A, Lehmann S, O’Kelly J, Kumagai T, Desmond JC, Pervan M, McBride WH, Kizaki M, Koeffler HP. Capsaicin, a component of red peppers, inhibits growth of androgen-independent, p53 mutant prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3222, 3229. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obach RS. Mechanism of cytochrome P4503A4- and 2D6-catalyzed dehydrogenation of ezlopitant as probed with isotope effects using five deuterated analogs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1599, 1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olajos EJ, Salem H. Riot control agents: pharmacology, toxicology, biochemistry and chemistry. J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:355, 391. doi: 10.1002/jat.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson A. Biotransformation of xenobiotics. In: Klaassen CD, editor. Casarett & Doull’s Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2001. pp. 133–224. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Crouch DJ, Yost GS. Quantitative analysis of capsaicinoids in fresh peppers, oleoresin capsicum and pepper spray products. J Forensic Sci. 2001a;46:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Crouch DJ, Yost GS, Fatah AA. Determination of capsaicin, dihy-drocapsaicin, and nonivamide in self-defense weapons by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2001b;912:259–267. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00574-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Ehlhardt WJ, Jackson DA, Kulanthaivel P, Mutlib AE, Espina RJ, Moody DE, Crouch DJ, Yost GS. Metabolism of capsaicin by cytochrome P450 produces novel dehydrogenated metabolites and decreases cytotoxicity to lung and liver cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002a;16:336–349. doi: 10.1021/tx025599q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Johansen ME, Lanza DL, Lee J, Lim JO, Yost GS. Calcium-dependent and independent mechanisms of capsaicin receptor (TRPV1)-mediated cytokine production and cell death in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2005;19:266, 275. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Taylor JL, Lanza DL, Carr BA, Crouch DJ, Yost GS. Capsaicinoids cause inflammation and epithelial cell death through activation of vanilloid receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2003b;73:170–181. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Veranth JM, Veronesi B, Yost GS. Vanilloid receptors in the respiratory tract. In: Gardner D, editor. Toxicology of the Lung. 4. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 297–349. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CA, Yost GS. Structural and enzymatic parameters that determine alkyl dehydrogenation/hydroxylation of capsaicinoids by cytochrome p450 enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:530, 536. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettie AE, Boberg M, Rettenmeier AW, Baillie TA. Cytochrome P-450-catalyzed desaturation of valproic acid in vitro. Species differences, induction effects, and mechanistic studies. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:13733, 13738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettie AE, Rettenmeier AW, Howald WN, Baillie TA. Cytochrome P-450–catalyzed formation of delta 4-VPA, a toxic metabolite of valproic acid. Science. 1987;235:890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.3101178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettie AE, Sheffels PR, Korzekwa KR, Gonzalez FJ, Philpot RM, Baillie TA. CYP4 isozyme specificity and the relationship between omega-hydroxylation and terminal desaturation of valproic acid. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7889–7895. doi: 10.1021/bi00024a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins W. Clinical applications of capsaicinoids. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:S86–89. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200006001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangyuttikarn W, Appleton ML, Yost GS. Metabolism of 3-methylindole in human tissues. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991;19:977, 984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeque AJ, Fisher MB, Korzekwa KR, Gonzalez FJ, Rettie AE. Human CYP2C9 and CYP2A6 mediate formation of the hepatotoxin 4-ene-valproic acid. J Pharma-col Exp Ther. 1997;283:698, 703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiles GL, Yost GS. Mechanistic studies on the cytochrome P450-catalyzed dehydrogenation of 3-methylindole. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:291, 297. doi: 10.1021/tx9501187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skordos KW, Laycock JD, Yost GS. Thioether adducts of a new imine reactive intermediate of the pneumotoxin 3-methylindole. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998a;11:1326–1331. doi: 10.1021/tx9801209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skordos KW, Skiles GL, Laycock JD, Lanza DL, Yost GS. Evidence supporting the formation of 2,3-epoxy-3-methylindoline: a reactive intermediate of the pneumotoxin 3-methylindole. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998b;11:741–749. doi: 10.1021/tx9702087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeal SJ, Reilly CA, Yost GS. Inactivation of cytochrome P450 2E1 by capsaicin. The Toxicologist, Toxicol Sci. 2002;66(1–S):22. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CG, Stopford W. Health hazards of pepper spray. N C Med J. 1999;60:268, 274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyman T, Stewart MJ, Steenkamp V. A fatal case of pepper poisoning. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;124:43, 46. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffee CH, Lantz PE, Flannagan LM, Thompson RL, Jason DR. Oleoresin capsicum (pepper) spray and “in-custody deaths. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1995;16:185–192. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Reilly CA, Yost GS. P450-Mediated bioactivation by dehydrogenation of chemicals produces electrophilic intermediates. BRI 2006 Proceedings; Tucson, AZ. January 2006.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Surh YJ. More than spice: capsaicin in hot chili peppers makes tumor cells commit suicide. JNCI. 2002;94:1263–1265. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.17.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh YJ, Ahn SH, Kim KC, Park JB, Sohn YW, Lee SS. Metabolism of capsaicinoids: evidence for aliphatic hydroxylation and its pharmacological implications. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL305–311. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh YJ, Lee SS. Capsaicin, a double-edged sword: toxicity, metabolism, and chemo-preventive potential. Life Sci. 1995;56:1845, 1855. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Appendino G. Vanilloid receptor TRPV1 antagonists as the next generation of painkillers. Are we putting the cart before the horse? J Med Chem. 2004;47:2717–2723. doi: 10.1021/jm030560j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Mechanisms and therapeutic potential of vanilloids (capsaicin-like molecules) Adv Pharmacol. 1993;24:123, 155. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60936-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159, 212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Khono H, Sakata K, Yamada Y, Hirose Y, Sugie S, Mori H. Modifying effects of dietary capsaicin and rotenone on 4-nitroquinolone-1-oxide-induced rat tongue car-cinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1361–1367. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.8.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DC, Perera K, Krol ES, Bolton JL. o-Methoxy-4-alkylphenols that form quinone methides of intermediate reactivity are the most toxic in rat liver slices. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:323, 327. doi: 10.1021/tx00045a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RQ, Phinney KW, Sander LC, Welch MJ. Reversed-phase liquid chromatography and argentation chromatography of the minor capsaicinoids. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005a;381:1432–1440. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RQ, Phinney KW, Welch MJ, White ET. Quantitative determination of capsaicinoids by liquid chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005b;381:1441–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth B, Gannett P. Carcinogenicity of lifelong administration of capsaicin of hot pepper in mice. In Vivo. 1992;6:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walpole CS, Wrigglesworth R, Bevan S, Campbell EA, Dray A, James IF, Masdin KJ, Perkins MN, Winter J. Analogues of capsaicin with agonist activity as novel analgesic agents; structure-activity studies. 2. The amide bond “B-region”. J Med Chem. 1993a;36:2373–2380. doi: 10.1021/jm00068a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walpole CS, Wrigglesworth R, Bevan S, Campbell EA, Dray A, James IF, Masdin KJ, Perkins MN, Winter J. Analogues of capsaicin with agonist activity as novel analgesic agents; structure-activity studies. 3. The hydrophobic side-chain “C-region”. J Med Chem. 1993b;36:2381–2389. doi: 10.1021/jm00068a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walpole CS, Wrigglesworth R, Bevan S, Campbell EA, Dray A, James IF, Perkins MN, Reid DJ, Winter J. Analogues of capsaicin with agonist activity as novel analgesic agents; structure-activity studies. 1. The aromatic “A-region”. J Med Chem. 1993c;36:2362–2372. doi: 10.1021/jm00068a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost GS. Mechanisms of 3-methylindole pneumotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 1989;2:273, 279. doi: 10.1021/tx00011a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Hamilton SM, Stewart C, Strother A, Teel RW. Inhibition of liver microsomal cytochrome P450 activity and metabolism of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK by capsaicin and ellagic acid. Anticancer Res. 1993;13:2341, 2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Huynh H, Teel RW. Effects of orally administered capsaicin, the principal component of capsicum fruits, on the in vitro metabolism of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK in hamster lung and liver microsomes. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:1093, 1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]