Abstract

Objective

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of random urine protein-creatinine ratio for the prediction of significant proteinuria in patients with preeclampsia.

Study design

155 pregnant patients diagnosed to have hypertension in late pregnancy were instructed to collect urine during a 24-hour period. Protein-creatinine ratio was evaluated in a random urinary specimen. Out of these, 120 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The predictive value of the random urinary protein-creatinine ratio for the diagnosis of significant proteinuria was estimated by using a 300-mg protein level within the collected 24-hour urine as the gold standard.

Results

104 patients (86.67%) had significant proteinuria. There was significant association between 24-hour protein excretion and the random urine protein-creatinine ratio (rs=0.596, P < .01). With a cut-off protein-creatinine ratio greater than 1.14 as a predictor of significant proteinuria, sensitivity and specificity were 72% and 75%, respectively. The positive predictive value was 94.9% and negative predictive value was 29.2%.

Conclusion

The random urine protein-creatinine ratio was not a good predictor of significant proteinuria in patients with preeclampsia.

Introduction

Preeclampsia, which accounts for most hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, is defined as a systolic blood pressure level of 140 mm Hg or higher or a diastolic blood pressure level of 90 mm Hg or higher that occurs after 20 weeks of gestation with proteinuria.[1] Proteinuria is an important sign of preeclampsia, and diagnosis is questionable in its absence. Significant proteinuria is described as 300 mg or more of urine protein per 24-hour period. The gold standard for diagnosis of significant proteinuria is 24-hour urine collection, but 24-hour urine collection is inconvenient for women, costly, and may be inaccurate due to incomplete collection. This is also associated with delayed diagnosis and management. Various methods have been used to shorten the time period to diagnose preeclampsia.

In recent years, random urinary protein-creatinine ratio has been suggested as a rapid test for prediction of significant proteinuria.[2–5] However, the accuracy of the test still remains unclear. Many studies have shown a good correlation between random urinary protein/creatinine ratio and 24-hour protein excretion,[2,3] while others have found it to be of limited use.[4,5] In many studies that have investigated random protein-creatinine ratios, predictive values of test results are not available.[2–4]

A rapid and accurate test may provide efficient inpatient and outpatient monitoring of proteinuria and may shorten the duration of hospitalization. Thus, the study was conducted to determine the diagnostic accuracy of random urine protein-creatinine ratio. Accuracy is defined as to what extent the test accurately measures what it purports to measure. Thus, this study was carried out to assess the value of protein-creatinine ratio in prediction of 24-hour urine total protein among women with preeclampsia.

Material and Methods

This study included 155 subjects who were diagnosed to have hypertension in late pregnancy. Participants in the study were inpatients on bed rest at Nehru Hospital, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. After admission, detailed medical, obstetrical, and menstrual history was taken, followed by physical and systemic examinations. These subjects were investigated and treated according to existing protocol within the department of the institute, for the management of hypertension according to severity. Patients with chronic hypertension and intrinsic renal disease were not included in the study. Clearance from the ethical committee of the medical center was obtained for the study.

All women, irrespective of the severity of the disease, were asked to provide a 24-hour urine collection for determination of proteinuria. The subjects were advised to pass urine at 8:00 am and collect all the urine subsequently till 8:00 am the next morning (24-hour period). The adequacy of urine collection was determined by creatinine excretion. Patients were excluded if they had coexisting urinary tract infection or inadequate specimen. Random sample for protein-creatinine ratio was collected the next morning after the 24-hour collection was over.

Urinary protein quantitation was done by Biuret method, and urinary creatinine estimation was done by modified Jaffe's method.[6,7] Protein-creatinine ratio and 24-hour protein excretion were assessed by Spearman correlation coefficient. Sensitivity and specificity of random urine protein-creatinine ratio at various cut offs for prediction of significant proteinuria were estimated using the results of 24-hour urine collection as gold standard. A receiver operating characteristic curve was constructed, and the area under the curve was estimated with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Out of a total of 155 patients, 10 were excluded because of inadequate specimen collection and 6 patients had coexisting urinary tract infections. Nineteen patients had no proteinuria and were not included in the study group. One hundred twenty patients constituted our study group. Table 1 shows demographic data for the patients enrolled in the study. The mean age of patients was 26 years, and the mean gestational age was 32 weeks. Sixty-six percent of the patients were primigravidas.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Subjects

| Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26 ± 4 | 22 | 30 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 32 ± 8 | 24 | 40 |

| 24-hour proteinuria (mg/24 hours) | 1.331 ± 1.153 | 0.1 | 7.6 |

| Protein-creatinine ratio (mg/dL) | 2.32 ± 2.505 | 0.05 | 14.50 |

SD = standard deviation

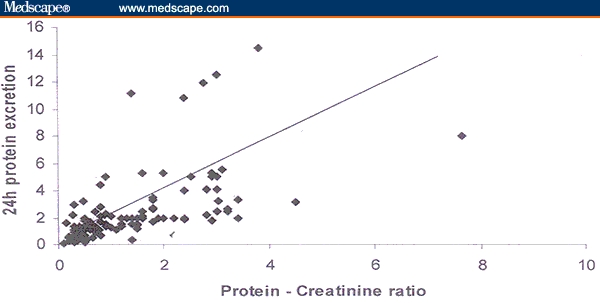

One hundred four patients (86.67%) had significant proteinuria in 24-hour urine collection. Twenty-two patients (18.3%) had proteinuria greater than 2 g, and only 3 patients (2.5%) had proteinuria greater than 5 g in 24-hour urine collection. The mean protein excretion was 1.33 g (range, 0.1–7.6). The Spearman correlation coefficient between 24-hour urine protein excretion and random urine protein-creatinine ratio was 0.596 (P < .01). Figure 1 demonstrates this relationship between 24-hour protein excretion and protein-creatinine ratio.

Figure 1.

Relationship between 24-hour protein excretion and random protein-creatinine ratio (r2 = 0.596; P < .01).

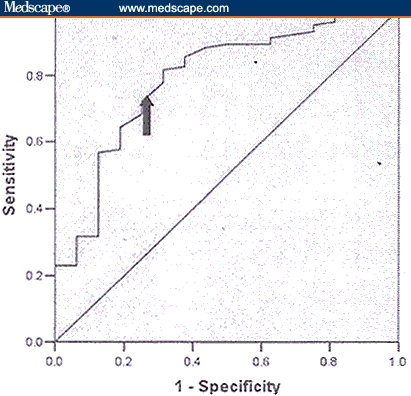

The receiver operating characteristic curve for random urine protein-creatinine ratio is shown in Figure 2. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve is 0.79 (95% CI 0.67–0.91; P < .001). Sensitivity and specificity for various cut offs of protein-creatinine ratio are shown in Table 2. With a cut off protein-creatinine ratio greater than 1.14 as a predictor of significant proteinuria, sensitivity and specificity were 72% and 75%, respectively. With this cut off, the positive predictive value was 94.9% and negative predictive value was 29.2% (ie, patients with a PC ratio 1.14 or higher were 95% likely to have significant proteinuria). A cut off point that yields 100% specificity was not available. Thus, a positive ratio (1.14 or higher) is indicative of disease and could lead to a management decision, but a negative test isn't very helpful.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curve for various cut offs (area under the curve is 0.79 [95% CI 0.67–0.91; P < .001]).

Table 2.

Predictive Values of Protein-Creatinine Ratio for Detection of Significant Proteinuria With Various Cut Offs

| Cut Off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (%) | Negative Predictive Value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.66 | 85.6 | 63 | 92 | 40 |

| 1.06 | 80.8 | 69 | 94.25 | 33.3 |

| 1.14 | 72 | 75 | 94.9 | 29.2 |

| 1.27 | 69.2 | 75 | 94.9 | 29.2 |

| 1.35 | 64.4 | 82 | 95.7 | 26 |

Discussion

This study was conducted to evaluate the correlation between significant proteinuria and random urinary protein-creatinine ratio and to determine its accuracy. A rapid and accurate test may avoid the inconvenience for the patient and will also avoid the delay in management and diagnosis. This study included a large number of patients with mild preeclampsia (68.33%).

Previous studies to evaluate the role of random protein-creatinine ratio have shown controversial results. Studies by Boler and associates,[2] and Jaschevatzky and associates[3] have shown excellent correlation between 24-hour proteinuria and random urinary protein-creatinine ratio. Boler and associates[2] studied the 2 parameters in 54 patients. Excellent correlation was achieved (r=0.9935; P < .0001) between the two, and this was achieved for normal pregnancies, hypertensive pregnancies, and multiple gestation. This study did not specify the number of patients with preeclampsia. In patients with proteinuria of more than 1 g/24 hours, there were variations in the results. Similarly, the study conducted by Jaschevatzky and associates[3] on 35 preeclamptic patients and 70 healthy patients found close correlation (r=0.9278; P < .001) between 24-hour proteinuria and random urinary protein-creatinine ratio. However, in patients with proteinuria greater than 2 g, the degree of correlation decreased. In both studies, sample size was smaller than in this study, and predictive values of the tests were not available.

Durnwald and colleagues[4] studied the value of protein-creatinine ratio in prediction of 24-hour urine total protein among women with preeclampsia. In this study of 220 women, it was apparent that protein-creatinine ratio and 24-hour urine total protein level showed a poor correlation with negative predictive value of 47.5% and specificity of 55.8%. Similarly, Al and colleagues[5] performed their study in 185 pregnant women, 39 of whom had preeclampsia (21%). Though there was significant association between 24-hour protein and random protein-creatinine ratio (r=0.56, P < .01), with a cut off protein-creatinine ratio greater than 0.19 as a predictor of significant proteinuria, sensitivity and specificity were 85% and 73%. Positive and negative predictive values were 46% and 95%, respectively. In our study, we also found significant association between the 2 parameters (r=0.596; P < .01). Sensitivity and specificity with predictive values for various cut offs of protein-creatinine ratio were studied (Table 2). With a cut off of 1.14, there were 4 false-positive and 29 false-negative results. With this cut off, positive and negative predictive value were 94.9% and 29.2%, respectively. The patients with false-negative results had proteinuria in the range of 0.3–1.5 g. Thus, higher values of proteinuria correlated with protein-creatinine ratio. Out of 120 patients, 22 patients had proteinuria greater than 2 g/24 hours and only 3 patients had proteinuria greater than 5 g/24 hours, which is an inadequacy of this study. However, none of the patients with proteinuria greater than 2 g was missed using protein-creatinine ratio testing. The results of protein-creatinine ratio had lower specificities and negative predictive values and did not vary greatly with an increasing cut off point (Table 2). There were higher numbers of false-negative results with various cut offs.

In conclusion, random protein-creatinine ratio is a poor predictor of 24-hour proteinuria. But as the amount of proteinuria increases, the correlation increases and false-negative results decrease. Therefore, this test can predict severe preeclampsia and thus can be used for rapid diagnosis of severe preeclampsia, especially where decisions of termination of pregnancy have to be made. However, this test cannot rule out mild preeclampsia and should not replace 24-hour urinary protein estimation.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: A Prospective Comparison of Random Urine Protein-Creatinine Ratio vs 24-hour Urine Protein in Women With Preeclampsia See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at chddialysis@rediffmail.com or to George Lundberg, MD, Editor in Chief of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Contributor Information

N. Aggarwal, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

V. Suri, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

S. Soni, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

V. Chopra, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

H. S. Kohli, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

References

- 1.Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap C, Hauth JC, Wenstrom KD, editors. Willams Obstetrics. 21st edition. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy; p. 568. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boler L, Zbella EA, Gleichea N. Quantitation of proteinuria in pregnancy by use of single voided urine samples. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:99–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaschevatzky OE, Rosenberg RP, Shalit A, Zondea HB, Grunstein S. Protein/creatinine ratio in random urine specimens for quantitation of proteinuria in pre-eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:604–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durnwald C, Mucer B. A prospective comparison of total protein/creatinine ratio versus 24 hour urine protein in women with suspected preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:848–852. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al RA, Baykal C, Karacay O, Geyik PO, Altun S, Dolen I. Random urine protein-creatinine ratio to predict proteinuria in new onset mild hypertension in late pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:367–371. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000134788.01016.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wootton IDP. Microanalysis in Medical Biochemistry. 4th edition. London: J and A Churchill Ltd; 1964. Urine protein estimation; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chasson AL, Crady HJ, Stanlay MA. Determination of creatinine by means of automated chemical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1961;35:83–88. [Google Scholar]