Abstract

Background and Purpose: Locomotor training (LT) enhances walking in adult experimental animals and humans with mild-to-moderate spinal cord injuries (SCIs). The animal literature suggests that the effects of LT may be greater on an immature nervous system than on a mature nervous system. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of LT in a child with chronic, incomplete SCI.

Subject: The subject was a nonambulatory 4½-year-old boy with an American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) C Lower Extremity Motor Score (LEMS) of 4/50 who was deemed permanently wheelchair-dependent and was enrolled in an LT program 16 months after a severe cervical SCI.

Methods: A pretest-posttest design was used in the study. Over 16 weeks, the child received 76 LT sessions using both treadmill and over-ground settings in which graded sensory cues were provided. The outcome measures were ASIA Impairment Scale score, gait speed, walking independence, and number of steps.

Result: One month into LT, voluntary stepping began, and the child progressed from having no ability to use his legs to community ambulation with a rolling walker. By the end of LT, his walking independence score had increased from 0 to 13/20, despite no change in LEMS. The child's final self-selected gait speed was 0.29 m/s, with an average of 2,488 community-based steps per day and a maximum speed of 0.48 m/s. He then attended kindergarten using a walker full-time.

Discussion and Conclusion: A simple, context-dependent stepping pattern sufficient for community ambulation was recovered in the absence of substantial voluntary isolated lower-extremity movement in a child with chronic, severe SCI. These novel data suggest that some children with severe, incomplete SCI may recover community ambulation after undergoing LT and that the LEMS cannot identify this subpopulation.

Locomotor training (LT) is a promising experimental approach that has been translated to humans to promote the recovery of walking after incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI).1,2 By using a treadmill as the environment in which to stimulate and practice stepping, this physiologically based strategy is believed to trigger and enhance intrinsic plasticity of the spinal cord central pattern generators for locomotion (SPGL).1,3–5 The clinical literature suggests that substantial lower-extremity (LE) isolated movements, as assessed by Lower Extremity Motor Score (LEMS) of the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS),6 are required for recovery of walking.7,8 The possibility for promoting effective functional repair with rehabilitation and other therapeutic modalities has increased due to mounting basic science evidence for training effects on neurotrophin expression,9 as well as the spinal cord's inherent potential for neural circuit reorganization.10–12

Although LT enhances walking ability (ie, improved speed, endurance, obstacle negotiation, step symmetry) in adult experimental animals and humans with mild-to-moderate motor incomplete SCI, the impact of activity-based therapy after trauma to the immature spinal cord should be even more significant. This premise is based on animal evidence showing that the acutely injured, developing spinal cord has substantial capacity for recovery, either spontaneously13,14 or when provided with LT.15,16 However, apart from epidemiological studies17 and the general notion that pediatric patients are likely to show better functional outcomes than older individuals,18,19 the clinical literature does not indicate how neuroplasticity in the young central nervous system might be exploited by newer rehabilitation strategies.

To explore this issue, we evaluated the effects of LT on a 4½-year-old boy who was nonambulatory 16 months after a low cervical SCI classified as AIS C. A series of evaluations were conducted in parallel with 76 sessions of intense, locomotor-specific training. This is the first report suggesting that LT is a viable strategy for promoting recovery of locomotion in children with chronic, severe SCI. This dramatic improvement also illustrates the need for other outcome measures and predictive indexes that are sensitive to the neuroplastic potential of the injured spinal cord, at least in children with SCI.

Method

Case Description and Medical History

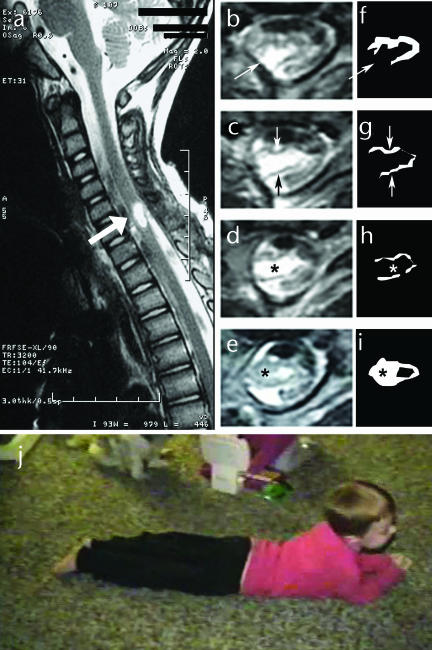

Prior to the child's accident at 3½ years of age, his mother reported that he showed normal motor development and was fully capable of walking, running, jumping, bicycle riding, and swimming. According to the medical chart, an accidental, self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest had occurred. The bullet entered at T3 and lodged near C6–7, with vertebral fractures from C7 to T1. A right subclavian artery pseudoaneurysm was repaired 1 day postinjury. Radiological evaluation showed bullet fragments from C2 to T1. A laminotomy at C5–7 was performed 48 hours later to remove the bullet. During removal, a partial severing of the spinal cord was noted. At 2½ weeks postinjury, the child's neurological status was classified as AIS A, C6 right and C7 left. Sagittal and axial images of the cervical spinal cord at 2 months postinjury showed an area of severe myelomalacia within the spinal cord from the mid-C5 vertebral level to the C6–7 disk space (Fig. 1, image a). Axial images (Fig. 1, images b–e) revealed destruction of the vast majority of spinal cord parenchyma, with replacement by a cyst of spinal fluid density. Only a small amount of preserved spinal cord tissue could be seen dorsally and ventrally bordering the cyst. Outlines of densities consistent with tissue are shown in Figure 1 (images f–i) to further illustrate lesion severity. Prognosis was wheelchair mobility and weaning from the ventilator.

Figure 1.

Consequences of spinal cord injury: (a) Acute T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance image (MRI) of spinal cord revealing central hemorrhagic necrosis at C6. Bold white arrow indicates lesion site. (b–e) Acute T2-weighted axial MRIs through the lesion epicenter. The ventral aspect of the spinal cord is at the top of the images, and the dorsal aspect is at the bottom. The fine white arrow in panel b indicates an area of complete tissue interruption in the dorsal lateral aspect of the spinal cord. The fine white arrow in panel c indicates a thin rim of ventral tissue, and the fine dark arrow indicates a thin rim of dorsal tissue. Between these tissue rims is a fluid-filled cyst. (f–i) Drawings of the remaining tissue corresponding to the axial MRIs shown in panels b through e. Asterisk in panels d and h represents the comparable area of lesion cavity. Asterisk in panels e and i is centered over tissue not present rostally. (j) Before training, the child's primary means of mobility outside of a standing frame or wheelchair: child pulling his body across the floor using only his arms.

Three weeks postinjury, the child entered inpatient rehabilitation for 3 months and during this time improved from AIS A to AIS C with bilateral C7 function. He then received 10+ months of outpatient therapy along with equipment ranging from a parapodium to reciprocal gait orthoses. However, he remained nonambulatory and could not stand independently. Medical record notations at 6 and 12 months postinjury described LE quadriceps femoris muscle activity with “a lot of extensor tone [which] looks more like spasticity [and] no voluntary hip flexion, ankle, or toe movement,” while improvement to C8 on the right at 7 months postinjury was documented.

The University of Florida Health Science Center Institutional Review Board approved this study, and the child's mother provided informed consent for participation and use of medical history in compliance with the US Health Information Portability and Accountability Act. Diagnosis was confirmed from medical chart review, magnetic resonance images from the child's acute hospitalization, and reassessments in the current study.

Clinical Neurologic, Sensorimotor, and Functional Assessments

Testing occurred over a 5-day (weekday) period preceding initiation of training and immediately following completion of training. Before and after completion of training, the child's neurological status and voluntary strength (force-generating capacity) were evaluated using the ASIA classification system of impairment.6 Further neurological evaluation included assessment of spasticity syndrome (passive resistance to stretch, hyperreflexia, and clonus), examining passive resistance to stretch using the Ashworth scale,20 with scores from 0 for no increase in muscle tone (velocity-dependent resistance to stretch) to 4 for rigid. Clonus was assessed using a quick stretch to the plantar-flexor muscles. Upper motor neuron injury was identified using the Babinski test.

Range of motion required for standing and walking was assessed for the hip, knee, and ankle joints. Standing and walking abilities were evaluated both over ground and on a treadmill with use of a body-weight–support (BWS) system (Neuro II)* and a pelvic and trunk harness.† When walking was self-initiated, gait speed was calculated using a 7.01-m (23-ft) computerized gait mat (GaitMat II)‡ for 2 trials each of self-selected and fastest walking. Walking trials and training sessions were videotaped for observational analysis of gait. Walking independence was assessed using the Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury, revised scale (WISCI-II),21 based on assistive device, bracing, and need for assistance. A step activity monitor (StepWatch)§ was used to quantify the number of community-based steps (outside of training) across a 2-day period at 4 time points beginning at session 49 and ending at session 74. Session 49 was selected as the starting point for assessing community-based steps because it coincided with when the child took his first voluntary steps during training (session 33) and then began to step in the home and community. The step activity monitor uses an accelerometer to indicate step frequency. Prior to use, the monitor is calibrated to the individual user's acceleration during swing and placed on the less-impaired limb.22 All standardized clinical assessments were performed by the physical therapists.

Locomotor Training

Training methods were as previously reported.2,23 Briefly, training consisted of 20 to 30 minutes of step training in the BWS and treadmill environment followed by 10 to 20 minutes of over-ground training. Trainers provided assistance at the pelvis and trunk and each lower limb. The lead trainers were 5 physical therapists, whereas the training team was composed of physical therapists, research assistants, an engineer, and undergraduate students. All trainers had completed a competency-based training program led by the primary investigator (ALB) or had previous experience working with adults with incomplete SCI and LT. A minimum of 3 trainers were required while training on the treadmill, with 1 trainer at the pelvis and trunk and 1 trainer on each leg. Initially, transfer of walking skills to over-ground training required 2 or 3 trainers. With progress, personnel requirements varied from 1 to 3 trainers. Training occurred 5 times per week for an initial 45 sessions. Due to lack of a plateau, sessions were added, for a total of 76 sessions. Training emphasized an upright posture and LE load bearing without upper-limb weight bearing, with the aim of approximating normal walking speed during treadmill-based training (0.8–1.2 m/s), pelvic and intralimb and interlimb coordination for the kinematics and spatial-temporal pattern of walking, and inclusion of arm swing.1,2,5,23 Each 5-minute bout of stepping was interspersed with a stand training bout of 5 minutes. During stand training, BWS was decreased to promote maximum loading. Following treadmill stepping, the skills practiced then were attempted over ground.

Trainers provided several types of sensory cues to facilitate stepping. Manual pressure creating stretches perpendicular to the iliopsoas and rectus femoris tendons and to the tibialis anterior tendon were used to promote flexor activity to initiate and promote swing. Manual pressure to the quadriceps femoris and Achilles tendons was used to promote extensor activity for load bearing during the stance phase. These cues were provided consistently, with deep pressure, during all stepping activities initially and then decreased as independence increased.

Results

AIS Outcomes

In our baseline evaluation of the child upon entering our program at 16 months postinjury, we classified his SCI neurological level as AIS C, C8 bilaterally. This was a slight improvement from the documented right C8 and left C7 in his medical records at 7 months postinjury. This status remained the same upon our examination after sessions 42 and 74 (Tab. 1). The child's LEMS, before and after training, was 4/50. This score reflected a substantial inability to isolate LE movements at the hip, knee, and ankle and is a poor prognosis for ambulation.7,8,24 Upon request for knee extension, the child inconsistently exhibited a whole-leg extension synergy involving the hip, knee, and ankle joints. The child could not stop, slow, or reverse the movement. Quadriceps femoris muscle voluntary strength at L3 was scored as “not tested,” as attempts at the single-joint movement of knee extension were accomplished as a whole-limb or whole-body synergistic movement that triggered extensor spasticity.25 Ankle plantar flexion initially was scored as 4 (a score of 2 for each leg), even though this movement was inconsistent bilaterally and had to be tested multiple times to see a response in the gravity-eliminated position. During the last week of LT (session 74) and 1 month after LT, left hip flexor tendon activity was palpable (score of 1). However, the score for right ankle plantar flexion decreased to 1 at both of these times, as movement was not seen, even with multiple trials, in the gravity-eliminated position. In contrast, substantial sensory sparing was seen below L1 at baseline and each testing time (Tab. 2). Perianal and anal sensation was spared, and the child's mother reported that he had developed an awareness of the need to void and to have a bowel movement.

Table 1.

American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale Motor Scores for the Left and Right Lower Extremities for Myotomes L2-S1 Before Training, After Session 42, After Session 74, and at the 1-Month Retention Test Following Completion of Traininga

0=total paralysis, 1=palpable or visible contraction, NT=not tested due to triggering of extensor synergy. L2=hip flexors (iliopsoas muscles), L3=knee extensors (quadriceps femoris muscles), L4=ankle dorsiflexors, L5=long toe extensors (extensor hallucis longus muscles), S1=ankle plantar flexors (gastrocnemius and soleus muscles). Maximum score for both lower extremities=50 (25/extremity). LEMS=Lower Extremity Motor Score.

Table 2.

Light Touch and Pinprick Tests for L1-S3 Dermatomes Before Training, After Session 42, After Session 74, and at 1-Month Retention Test Following Completion of Traininga

A modified score was used for light touch: a score of 1 indicated that the child correctly responded that light touch had occurred (including location), and a score of 0 indicated that the response was incorrect or that light touch perception was absent. For the pinprick test, a score of 1 indicated that the child correctly distinguished between dull and sharp sides of a pin, and a score of 0 indicated that child responded incorrectly and could not distinguish between dull and sharp sides of a pin. The child's ability to understand the scoring system and the reliability of his responses were first tested on his face. Maximum score for light touch or pinprick on each side=8.

At baseline and during LT, a positive Babinski sign was present bilaterally, indicating corticospinal tract damage. Using the Ashworth scale,20 passive resistance to knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion was scored as 2 (marked increase in tone, but affected body part is easily flexed) and 1 (slight increase in tone, giving a “catch” when body part is moved), respectively, denoting extensor spasticity. Clonus also was present bilaterally, consistent with upper motor neuron damage. Adequate passive hip and knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion range of motion for standing and walking were present.

Locomotor Recovery

At baseline, the child was nonambulatory. He pulled his body across the floor using only his arms in the home (Fig. 1j; Supplemental Video), and he used a wheelchair for community mobility. He was unable to stand independently and required maximal assistance at the trunk and legs to stay upright. When put into a stepping environment (treadmill or over ground), he showed no contribution to stepping, and his legs had to be passively moved throughout the entire step cycle.

Focus on flexor activity initiates swing and first steps.

The first 22 sessions of LT (ie, 5 sessions per week) had minor effects and led to only slight LE extensor activity during stance and improved shoulder alignment with the pelvis. At session 23, the intensity of the tibialis anterior tendon pressures given by the therapists was increased and cuing (pressure) of the hip flexor tendons was added, resulting in whole-limb flexion. These cues were timed to coincide with initiation of ipsilateral swing as the child's weight was shifted to the opposite limb. Repetitive steps on the treadmill and over ground were practiced with this additional cuing during weight transfer and transition from stance to swing (Supplemental Video).

Number and quality of step cycles.

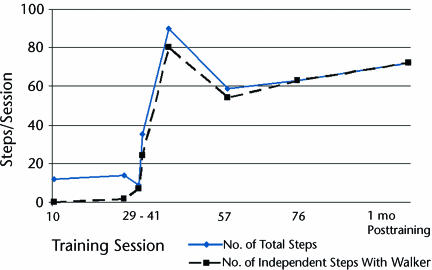

After 6 sessions of intense cuing of the LE flexors, the child made his first active contribution to stepping (session 29, Fig. 2). Within a series of 14 trainer-cued steps over ground, 2 noncued steps occurred on the right. Specifically, following a cued left leg step, the right leg initiated swing and continued into stance without cuing to that limb. Four sessions later, the child initiated and completed 7 consecutive steps over ground with no cuing (Fig. 2, session 33). This appeared to be a critical point, as the next day he initiated 24 of 35 steps without cuing, and this number continued to rapidly rise through session 41 (Fig. 2). The decrease in the number of steps taken after session 41 reflects the time period videotaped rather than his overall capacity. His increasing skill after session 41, however, was reflected in the percentage of independently initiated steps exhibited over ground with the rolling walker, which increased rapidly and steadily from 69% at session 34 to 100% at session 76 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Progression from wheelchair dependence to independent ambulation with a walker across the 76 sessions of locomotor training (LT) and at a 1-month retention test following completion of training: the total number of steps over ground per training session relative to the number of independent steps with a rolling walker. After treadmill-based LT sessions 1 through 9, no over-ground steps were attempted. Following treadmill-based LT sessions 10 through 29, the range in number of steps assisted over ground was 10 to 15. From session 23 to session 29, manual cueing of the tibialis anterior and iliopsoas muscles was intensified over ground, complementing the training on the treadmill. At session 29 and over ground, the first steps without direct cueing of the limb occurred (2/14 steps), although each step followed a contralaterally cued step. The decrease in the number of steps taken after session 41 and over ground reflects the period of videotaping rather than the child's overall capacity. His increasing skill after session 41, however, is reflected in the percentage of independently initiated steps exhibited over ground with the rolling walker, which increased rapidly and steadily from 69% at session 34 to 100% at session 76.

As walking improved, parallel changes in independence were seen. Initially, ambulation was disrupted by a scissoring pattern (ie, crossing of one ankle onto the other), which is qualitatively similar to what is seen after complete spinal transection in cats.26 Initially, consistent manual assistance was required for the child to uncross his legs. As training progressed, scissoring was less disruptive as he developed the ability to independently pull his foot past the other limb.

Progression to walker use.

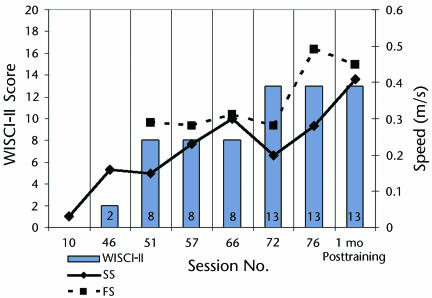

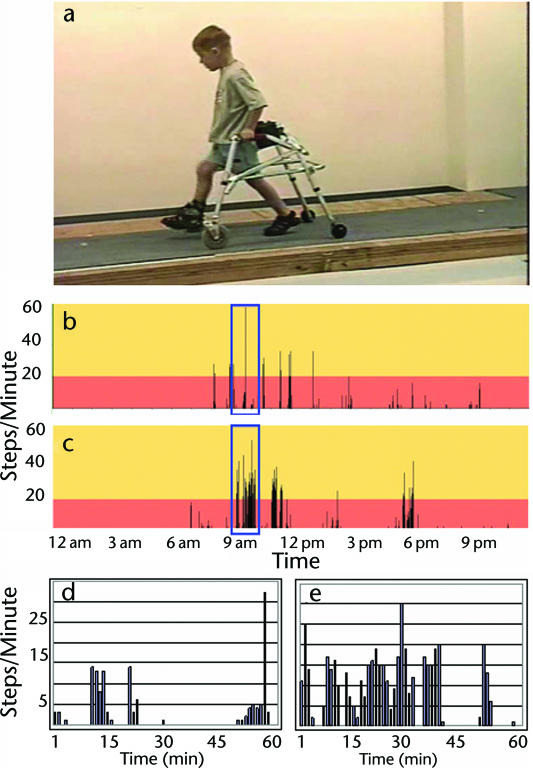

From session 51 (18 sessions after showing multiple noncued steps) to session 76, the child's self-selected (comfortable) gait speed increased from 0.19 m/s to 0.29 m/s. His fastest walking speed also improved from 0.3 m/s to 0.48 m/s (Fig. 3). Similarly, walking independence improved. The child advanced from a score of 0/20 to 13/20 on the WISCI-II21 (Fig. 3). This reflected a shift from total dependence to independent use of a rolling walker (Fig. 3, Supplemental Video). Once the child began using the walker for community ambulation, his number of steps increased rapidly. For example, community-based activity improved from 926 steps per day (after session 49) to 2,488 steps per day (after session 74) (Fig. 4) while walking with a nonpivoting, posterior rolling walker with pelvic stabilizers (Fig. 4). A pelvic stabilizer is a small, 3-sided pad inserted into the rear of the walker. The pad, if contacted while walking, provides some posterolateral support at the pelvis. For each 4-day period of stepping activity, the hour demonstrating the greatest stepping activity was selected for further analysis. Across the time points evaluated, the capacity for walking improved from 280 steps per hour to 956 steps per hour, with the percentage of steps walked at a cadence greater than 20 steps per minute increasing from 8.3% (session 49) to 43.3% (session 74) (Fig. 4). In addition, the child could stop, make wide turns, speed up, and slow down with his walker.

Figure 3.

Progression of self-selected (SS) and fastest (FS) gait speed (meters per second) walking over ground with a rolling walker or with manual assistance and ranked by the Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II (WISCI-II) across training sessions and at the 1-month retention test following completion of training.

Figure 4.

Independent walking. (a) Using a rolling walker at 1-month follow-up after completion of training. (b, c) Amount of self-selected walking in the home and community for a 24-hour period following 2 different training sessions: (b) 936 steps after session 49 (week 10), (c) 2,488 steps after session 74 (week 16). (d, e) The most productive hour of walking from data sets b and c, respectively, and demonstrating the greatest capacity of the child for walking activity: (d) 280 steps in 1 hour with 8.3% of steps at >20 steps/min after session 49, (e) 956 steps in 1 hour with 43.3% of steps at >20 steps/min after session 74.

Although improved trunk alignment on the treadmill transferred to over-ground training, the walker was still required for upright balance and support. Although the child's arms initially hung anterior and lateral to his body, they were no longer passive by the end of the LT program. Typically, his arms were flexed approximately 90 degrees at the elbow, with slight internal rotation at the shoulder. On rare occasions, intermittent bouts of stepping in which arm swing was coordinated with the contralateral leg were seen at treadmill speeds greater than 1.0 m/s (Supplemental Video). Prior to volitional stepping, training with manual assistance typically occurred with 40% to 50% of BWS at 0.3 to 0.6 m/s. This training progressed to 30% to 40% of BWS at 0.8 m/s and to 15% to 20% of BWS at 1.2 m/s by the end of the study. Manual assistance at the trunk and pelvis and the legs for training in stepping and standing began at maximal to moderate assistance and progressed to minimal assistance at the trunk and legs from session 36 through completion of training.

Recovery Is Locomotor Dependent

The substantial recovery was observed only within the context of a reciprocal stepping pattern during walking. Although the child had voluntary control over basic features of stepping (eg, initiation, termination, speed change), he could not demonstrate isolated joint movements within or outside the context of locomotion, with the exception of inconsistent plantar flexion. For example, he was unable to produce isolated LE movements such as knee extension independent of hip and ankle movements while standing, walking, sitting, or lying supine. Prior to training, he inconsistently demonstrated a trunk, hip, knee, and ankle extensor synergy when asked to extend his knee during isolated manual muscle testing. The synergy was slow to arise and then irreversible. At the end of the LT program, bilateral LE alternating flexion and extensor rhythmic activity could be initiated in a supine position (maximum of 10 cycles). However, the pattern could be initiated only if a limb was flexed. This ability was not present prior to training, and the child appeared as if he were stepping in the air.

Although the reciprocal, rhythmic stepping pattern recovered, the child did not demonstrate any LE postural responses. Additionally, he could stand independently with a rolling walker, but he could not stand without external support or independently move from a sit-to-stand position.

Functional Locomotor Recovery Maintained

At a 1-month follow-up evaluation, no decrease in functional ambulation was seen. The child continued to be independent with the rolling walker on a level surface, and the percentage of self-initiated steps exhibited over ground was still 100%. Although his fastest walking speed was similar to that seen during his last training session, his usual self-selected walking speed had increased from 0.28 to 0.41 m/s.

The child's primary means of home and community mobility changed from upper-extremity crawling or wheelchair propulsion to walking independently with a walker and occasional wheelchair use. Four months after completion of LT, he attended kindergarten and walked independently with full-time use of a walker.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our findings show remarkable context-dependent ambulatory recovery following LT of a young subject with incomplete cervical SCI whose neurological status predicted little, if any, probability of ambulatory recovery. These results assume added significance in view of the fact that he was 16 months post-SCI, he could not use his legs, and his LE status had not changed for at least a year. His significant disability was consistent with the severe spinal disruption seen with magnetic resonance imaging. Despite his remarkable recovery of community ambulation with a rolling walker, there were no parallel changes in LEMS. Although other authors2,5,8,27–29 also have reported the benefits of LT for improving walking without significant changes in LEMS in people with motor incomplete SCI, our findings suggest that LT may be used to promote walking in individuals who are nonambulatory in the absence of substantial voluntary LE isolated movements.28

Scrutiny of the literature revealed reports of only 2 individuals with severely limited LEMS outcomes who achieved some ability to walk post-SCI.27,29 Both were adults, and their recovered walking abilities were inferior to those reported here. The first individual, who had no clinic-based, formal training but who taught himself the skills necessary to elicit a step and standing response to achieve very limited walking, had LEMS outcomes comparable those of our subject, although his neurological level of injury was lower (T3) and his recovered walking with a rolling walker was limited to 40 m at only 0.1 m/s.27 The second individual, who had limited but higher LEMS outcomes than those of our subject, recovered the ability to walk only 20 to 40 m with a rolling walker after LT (no speed reported).29 Moreover, findings with robotic-assisted LT indicate no success in achieving ambulatory status in adults who are nonambulatory prior to training.30 Although our study adds a third report of walking recovery in an individual with severe SCI who would not be predicted to walk based upon LEMS outcomes, it is distinctly different in the superior functional outcomes achieved in comparison with the 2 adults with incomplete SCI. We report recovery of full-time community ambulation with a rolling walker and the ability to achieve walking speeds of up to 0.48 m/s.

Locomotor training provides task-specific, mass practice that is believed to activate spinal circuitry for stepping using locomotor-appropriate sensory input. The reported findings support the idea that this activation ultimately may lead to greater SPGL activity and associated motoneuron output following SCI. Furthermore, the temporal progression seen in this child supports the idea that recovery may be promoted by 2 components of LT. One component activates the SPGL using only sensory input and is only facilitated by the trainers.3,31 The other component incorporates voluntary activation of the pattern (SPGL) by the participant, which is then perpetuated by sensory input.

The recovery seen was entirely task-dependent; voluntarily leg movement occurred only within the context of a simple, reciprocal stepping pattern. The child's ability to initiate and terminate this basic stepping pattern suggests some supraspinal control.32 However, his inability to modify the pattern or show balance responses suggests that this descending control was limited and that the pattern is primarily organized and perpetuated at the spinal level by the SPGL, motoneurons, and spinal afferents. This is further supported by the child's ability by the end of LT to initiate, but not perpetuate, a stepping pattern while positioned supine. However, the ability to initiate the stepping pattern in a supine position occurred only if the first cycle was assisted by flexing a limb. This dependence on flexion, as well as the inability to sustain the pattern, suggests the critical contribution of sensory feedback during stepping and weight bearing for this child. Animal studies support the importance of cues for walking, including the transition from stance to swing (extension to flexion).33

AIS motor scores—specifically the LEMS, which indicates isolated, voluntary movements—are relied upon heavily to predict locomotor potential and report recovery.24 In the current study, however, the LEMS was not predictive of locomotor recovery even after walking was achieved. The emergence of stepping activity and initiation without changes in isolated voluntary leg activity suggests that a paradigm shift is necessary in our clinical model to predict ambulatory potential after SCI or to judge therapeutic efficacy in the absence of obvious voluntary control below the level of the SCI. This perhaps is not surprising, as AIS-related indexes are believed to reflect recovery from injury during the acute-to-subacute post-SCI phase34,35 and were developed to reflect neurological level of sparing rather than novel forms of functional neuroplasticity. Thus, this case provides a compelling illustration of why development of additional measures of motor control are needed.36,37 A significant challenge in this regard is to recognize the minimal features that identify the potential for activating the intrinsic mechanisms of the nervous system through LT to effect recovery of walking.28,29 Although the accuracy and reliability of manual muscle and sensory testing in children have recently been questioned,38 at baseline this child, nonetheless, did not perform any spontaneous or voluntary isolated leg movements in his daily activities, could not stand, and was nonambulatory. The child did follow verbal instructions for limb movement testing, and sensory test instructions were simplified for greater clarity and understanding.

Extensive literature in both lower vertebrates and mammals indicates that multiple supraspinal systems may activate the SPGL. In contrast to the corticospinal tract, other supraspinal systems that affect locomotion originate subcortically and include the mesencephalic locomotor region in the brain stem.39–41 Brain-stem locomotor activation may be nonspecific compared with direct cortical activation, particularly if mediated through a diffuse projection such as the reticulospinal tract.39 Theoretically, a cortico-brain-stem-spinal system, such as the reticulospinal tract, could support voluntary activation of the SPGL without recovery of isolated voluntary leg movements. Subcortical mechanisms and their potential contributions to recovery in the human post-SCI have received little attention and may represent unrecognized or underappreciated potential substrates for rehabilitation. Newer techniques, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and diffusion tensor imaging, may help to shed light on these potential contributions in future studies.

Although LT is recognized as a promising strategy for enhancing locomotor recovery in adults with chronic, incomplete SCI and voluntary, isolated movements, a unique contribution of the present study is testing LT as an agent for recovery in the pediatric population. A recently published case report recounts the feasibility and benefits of LT within the acute stage after incomplete SCI in a child aged 5 years.42 Distinctly different from the current study is the concomitant improvement reported for the LEMS from 4/50 (1 month post-SCI) to 29/50 (6 months post-SCI) with behavioral improvements in walking. In the current study, no change in LEMS accounted for the change in walking capacity.

The potential beneficial effects of LT on the pediatric population are consistent with animal studies in which LT often is correlated with enhanced locomotor recovery following neonatal SCI,15,43 as well as those that suggest the injured developing spinal cord may show greater functional recovery than the mature system.14,44–46 However, parallels between animal studies identifying an “infant lesion effect” (greater recovery) and our study must be interpreted conservatively. In contrast to the animal studies in which lesions were made shortly after birth, prior to the establishment of weight-supported walking, and in the presence of developmental growth of certain descending pathways,16 our subject was an integrated walker at the time of injury, with a more advanced spinal substrate. Thus, the profound functional changes we describe not only suggest the merit of LT for a pediatric population paralleling the adult mild-to-moderate injuries currently targeted for training, but also suggest LT may be viable for more severe, chronic, incomplete pediatric SCI cases. Additionally, the viability of this strategy needs to be studied in more severe pediatric SCI cases, with careful documentation and quantification of the clinical picture and recovery process. This study identified a platform for more aggressively pursuing clinical research on locomotor training for people with severe, incomplete SCI.

Supplementary Material

Dr Behrman and Dr Howland provided concept/idea/research design and fund procurement. Dr Behrman, Ms Nair, Mr Bowden, Dr Reier, Dr Thompson, and Dr Howland provided writing. Dr Behrman, Ms Nair, Mr Bowden, Mr Herget, Ms Martin, Dr Phadke, Dr Senesac, and Dr Thompson provided data collection. Dr Behrman, Ms Nair, Mr Bowden, Dr Dauser, Dr Phadke, Dr Reier, Dr Thompson, and Dr Howland provided data analysis. Dr Dauser and Dr Senesac provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission). The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Dr Jeffrey Kleim, Dr Naomi Kleitman, Dr David Fuller, and Dr Pamela W Duncan for their helpful comments and advice during final preparation of the manuscript.

Portions of this work were presented at: (1) the Pediatric Spinal Cord Injury Conference, sponsored by Tingley Children's Hospital and Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of New Mexico; July 10, 2005; Albuquerque, NM; (2) the III STEP Symposium on Translating Evidence Into Practice: Linking Movement Science and Intervention, sponsored by the Neurology and Pediatrics Sections of the American Physical Therapy Association; July 15–21, 2005; Salt Lake City, Utah; (3) the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association; February 1–5, 2006; San Diego, Calif; (4) PT 2006: Annual Conference and Scientific Exposition of the American Physical Therapy Association; June 21–24, 2006; Orlando, Fla; (5) the Howard H Steel Conference: Injuries and Dysfunction of the Spinal Cord in Children; November 30-December 2, 2006; Lake Buena Vista, Fla; (6) the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association; February 14–18, 2007; Boston, Mass; and (7) the Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Spinal Injury Association; May 2007; Tampa, Fla.

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development-National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research grant K01 HD 01348-01, the Craig H Neilsen Foundation, the Anne and Oscar Lackner Professorship, and the University of Florida Brooks Center for Rehabilitation Studies, Jacksonville, Fla.

Vigor Equipment Inc, 4915 Advance Way, Stevensville, MI 49127-9544.

Robertson Mountaineering, PO Box 90086, Henderson, NY 89009-0086.

EQ Inc, 3469 Limekiln Pike, Chalfont, PA 18914.

Cyma Corp, 6405 218th St SW, Suite 100, Mountlake Terrace, WA 98043-2180.

References

- 1.Barbeau H. Locomotor training in neurorehabilitation: emerging rehabilitation concepts. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2003;17:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman AL, Lawless-Dixon AR, Davis SB, et al. Locomotor training progression and outcomes after incomplete spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1356–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJ, Bigbee AJ, et al. Plasticity of the spinal neural circuitry after injury. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:145–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz V, Harkema SJ. Locomotor activity in spinal cord-injured persons. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1954–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrman AL, Harkema SJ. Locomotor training after human spinal cord injury: a series of case studies. Phys Ther. 2000;80:688–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marino RJ, Barros T, Biering-Sorensen F, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26(Spring):50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters RL, Adkins R, Yakura J, Vigil D. Prediction of ambulatory performance based on motor scores derived from standards of the American Spinal Injury Association. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:756–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wirz M, van Hedel HJ, Rupp R, et al. Muscle force and gait performance: relationships after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1218–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Pinilla F, Ying Z, Roy RR, et al. Voluntary exercise induces a BDNF-mediated mechanism that promotes neuroplasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2187–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raineteau O, Fouad K, Bareyre FM, Schwab ME. Reorganization of descending motor tracts in the rat spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1761–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, et al. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raineteau O, Schwab ME. Plasticity of motor systems after incomplete spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown KM, Wolfe BB, Wrathall JR. Rapid functional recovery after spinal cord injury in young rats. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber ED, Stelzner DJ. Behavioral effects of spinal cord transection in the developing rat. Brain Res. 1977;125:241–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howland DR, Bregman BS, Tessler A, Goldberger ME. Development of locomotor behavior in the spinal kitten. Exp Neurol. 1995;135:108–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bregman BS, Goldberger ME. Anatomical plasticity and sparing of function after spinal cord damage in neonatal cats. Science. 1982;217(4559):553–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVivo MJ, Vogel LC. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury in children and adolescents. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27(suppl 1):S4–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massagli TL, Jaffe KM. Pediatric spinal cord injury: treatment and outcome. Pediatrician. 1990;17:244–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia RA, Gaebler-Spira D, Sisung C, Heinemann AW. Functional improvement after pediatric spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashworth B. Preliminary trial of carisoprodol in multiple sclerosis. Practitioner. 1964;192:540–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dittuno PL, Dittuno JF Jr. Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury (WISCI II): scale revision. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:654–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowden MG, Behrman AL. Step activity monitor: accuracy and test-retest reliability in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobkin B, Apple D, Barbeau H, et al. Weight-supported treadmill vs over-ground training for walking after acute incomplete SCI. Neurology. 2006;66:484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burns AS, Ditunno JF. Establishing prognosis and maximizing functional outcomes after spinal cord injury: a review of current and future directions in rehabilitation management. Spine. 2001;26:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reference Manual for the International Standards for Spinal Cord Injury. Rev ed. Chicago, Ill: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003.

- 26.Rossignol S, Chau C, Brustein E, et al. Locomotor capacities after complete and partial lesions of the spinal cord. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 1996;56:449–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wernig A, Muller S. Laufband locomotion with body weight support improved walking in persons with severe spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1992;30:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maegele M, Muller S, Wernig A, et al. Recruitment of spinal motor pools during voluntary movements versus stepping after human spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:1217–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wernig A, Nanassy A, Muller S. Laufband (LB) therapy in spinal cord lesioned persons. Prog Brain Res. 2000;128:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirz M, Zemon DH, Rupp R, et al. Effectiveness of automated locomotor training in patients with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury: a multicenter trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harkema SJ. Plasticity of interneuronal networks of the functionally isolated human spinal cord. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widajewicz W, Kably B, Drew T. Motor cortical activity during voluntary gait modifications in the cat, II: cells related to the hindlimbs. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2070–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van de Crommert HW, Mulder T, Duysens J. Neural control of locomotion: sensory control of the central pattern generator and its relation to treadmill training. Gait Posture. 1998;7:251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisler FH, Coleman WP, Grieco G, Poonian D. Measurements and recovery patterns in a multicenter study of acute spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26:68–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marino RJ, Ditunno JF Jr, Donovan WH, Maynard F Jr. Neurologic recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury: data from the Model Spinal Cord Injury Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1391–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curt A, Schwab ME, Dietz V. Providing the clinical basis for new interventional therapies: refined diagnosis and assessment of recovery after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kern H, McKay WB, Dimitrijevic MM, Dimitrijevic MR. Motor control in the human spinal cord and the repair of cord function. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1429–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz RR, Johansen KJ. The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: reliability of data when applied to children and youths. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossignol S, Dubuc R, Gossard JP. Dynamic sensorimotor interactions in locomotion. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:89–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jordan LM, Schmidt BJ. Propriospinal neurons involved in the control of locomotion: potential targets for repair strategies? Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whelan PJ. Control of locomotion in the decerebrate cat. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;49:481–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prosser LA. Locomotor training within an inpatient rehabilitation program after pediatric incomplete spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 2007. Jul 17; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Smith JL, Smith LA, Zernicke RF, Hoy M. Locomotion in exercised and nonexercised cats cordotomized at two or twelve weeks of age. Exp Neurol. 1982;76:393–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bregman BS, Goldberger ME. Infant lesion effect, II: sparing and recovery of function after spinal cord damage in newborn and adult cats. Brain Res. 1983;285:119–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bregman BS, Goldberger ME. Infant lesion effect, III: anatomical correlates of sparing and recovery of function after spinal cord damage in newborn and adult cats. Brain Res. 1983;285:137–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leonard CT, Goldberger ME. Consequences of damage to the sensorimotor cortex in neonatal and adult cats, II: Maintenance of exuberant projections. Brain Res. 1987;429:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.