Abstract

The mechanisms by which retinoids regulate initiation of mRNA translation for proteins that mediate their biological effects are not known. We have previously shown that all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) induces mTOR-mediated activation of the p70 S6 kinase, suggesting the existence of a mechanism by which retinoids may regulate mRNA translation. We now demonstrate that treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)-derived NB4 cells with ATRA results in dissociation of the translational repressor 4E-BP1 from the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4E, and subsequent formation of eIF4G-eIF4E complexes. We also show that siRNA-mediated inhibition of 4E-BP1 expression enhances ATRA-dependent upregulation of p21Waf1/Cip1, a protein that plays a key role in the induction of retinoid-dependent responses. Our data also establish that ATRA- or cis-RA-dependent p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression is enhanced in mouse embryonic fibroblasts with targeted disruption of the 4e-bp1 gene, in the absence of any effects on the transcriptional regulation of the p21Waf1/Cip1 gene. Moreover, generation of ATRA- or cis-retinoic acid (cis-RA)-antiproliferative responses is enhanced in 4E-BP1 knockout cells. Altogether, these findings strongly suggest a key regulatory role for the translational repressor 4E-BP1 in the generation of retinoid-dependent functional responses.

Introduction

ATRA and cis-RA (9-cis-RA, 13-cis-RA) are vitamin A derivatives with potent antitumor properties. ATRA exerts important antiproliferative and differentiation effects on leukemic cells in vitro and in vivo (1-5). The retinoids transduce signals by nuclear retinoic acid receptors: RAR (α,β,γ) activated by either ATRA or cis-RA; and RXR (α,β,γ) only activated by cis-RA (6,7). These receptors form homo- or hetero-dimers that bind to specific promoter elements, to regulate transcription of genes that mediate differentiation and growth inhibition, including p21Waf1/Cip1, C/EBPβ, and HoxA1 (6,7).

Although the mechanisms of retinoid-dependent gene-transcription are well-understood, little is known on the mechanisms by which retinoids regulate initiation of mRNA translation for protein products that mediate their biological effects. We previously reported that ATRA activates the mTOR/p70S6K pathway and induces phosphorylation of the translational-repressor 4E-BP1 (8), but the functional relevance of this pathway in the generation of retinoid-responses remains unknown. To directly address its role in retinoid-signaling, we used cells from mice with targeted disruption of 4e-bp1 gene. Our data demonstrate that ATRA-dependent upregulation of p21Waf1/Cip1, a protein that plays a key role in growth-inhibitory and pro-apoptotic responses (9-12), is enhanced in 4e-bp1 knockout-cells. Similarly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of 4E-BP1 in APL-derived cells results in p21Waf1/Cip1-upregulation. Importantly, antiproliferative responses are augmented in 4e-bp1 knockout-cells, suggesting that 4E-BP1 plays an important regulatory role in the generation of ATRA-mediated biological responses.

Material and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

NB4.300/6 cells (13) were provided by Dr. Saverio Minucci (European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy). ATRA and 13-cis-RA were purchased from Sigma. Rapamycin was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). An anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-4E-BP1, anti-eIF4E, and anti-eIF4G antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Beverly,MA). Immortalized MEFs from 4E-BP1 knockout-mice (14) were provided by Dr. Nahum Sonenberg (McGill University, Montreal, Canada).

Immunoprecipitations and Immunoblotting

Cells were incubated with ATRA or 13-cis-RA for the indicated times and lysed in phosphorylation lysis buffer (15,16). In experiments in which the effects of rapamycin were examined, rapamycin (20 nM) was added for 2.5 hours prior to cell lysis (8). Immunoprecipitations and immunoblotting were performed as in our previous studies (15, 16).

Cell Proliferation Assays

Cell proliferation was assessed using MTT assays, as in previous studies (17,18).

Transfections of small interfering RNAs

For the knockdown of 4E-BP1, a prevalidated siRNA mix from Santa Cruz (Carlsbad, CA ) was used. Cells were transfected using Amaxa Biosystems Nucleofector Kit V (Gaithersburg, MD).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

These studies were performed essentially as previously described (15).

Results

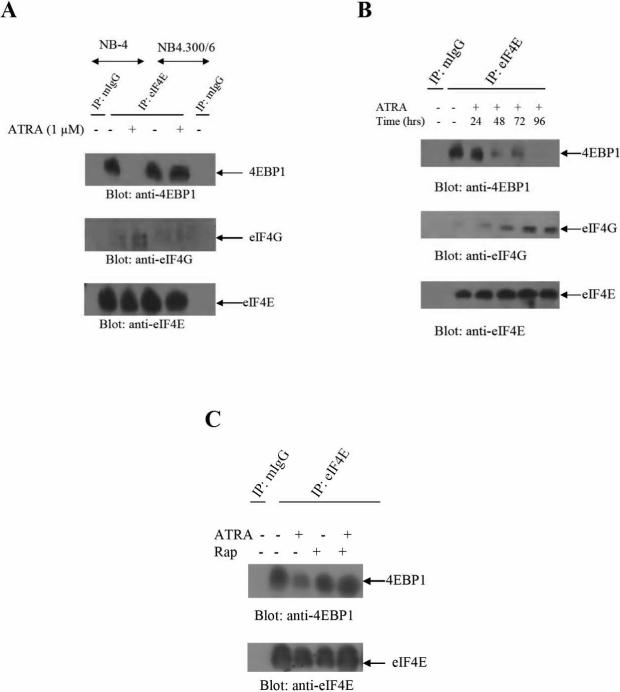

We initially examined the effects of ATRA on the assembly of the cap-dependent translation-initiation complex. Specifically, we examined the association of 4E-BP1 with eIF4E, as well as the formation of eIF4E-eIF4G complexes. NB4 cells were treated with ATRA, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-eIF4E antibody and immunoblotted with anti-4E-BP1 or anti-eIF4G antibodies. ATRA-treatment resulted in dissociation of 4E-BP1 from eIF4E and enhanced association of eIF4E with eIF4G (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, ATRA-treatment did not elicit dissociation of 4E-BP1 from eIF4E or formation of eIF4E/eIF4G complexes in the NB4.300/6 variant cell line (Fig. 1A) that is resistant to the differentiating and growth inhibitory effects of ATRA (13,18), suggesting that the formation of such complexes correlates with ATRA-sensitivity. ATRA-inducible dissolution of 4E-BP1/eIF4E complexes and formation of eIF4E/eIF4G complexes was time-dependent (Fig. 1B) and was seen at times at which growth-inhibitory effects and cell differentiation responses occur (8). Such decreased association of 4E-BP1 with eIF4E was reversible by treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (Fig. 1C), consistent with the fact that phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 is mTOR-dependent (8).

Figure 1.

ATRA-dependent assembly of cap-dependent translation initiation complex. A. NB4 or NB4 300.6 cells were treated with ATRA (1 μM) for seventy two hours, as indicated. Equal amounts of total cell lysates were subsequently immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-eIF4E antibody, or control mouse immunoglobulin (mIgG). Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by either 12.5% or 7% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against 4E-BP1 (upper panel), eIF4G (middle panel) or eIF4E (lower panel). B. NB4 cells were treated with ATRA as indicared and lysates were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-eIF4E antibody or control mouse mIgG. Immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for 4E-BP1 (upper panel), eIF4G (middle panel), and eIF4E (lower panel). C. NB4 cells were treated with ATRA for forty eight hours, as indicated, and then rapamycin (20 nM) was added to the cultures for two and half hours prior to cell lysis. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-eIF4E antibody or control mIgG. Immune-complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE for analysis of 4E-BP1 (upper panel) or eIF4E (lower panel).

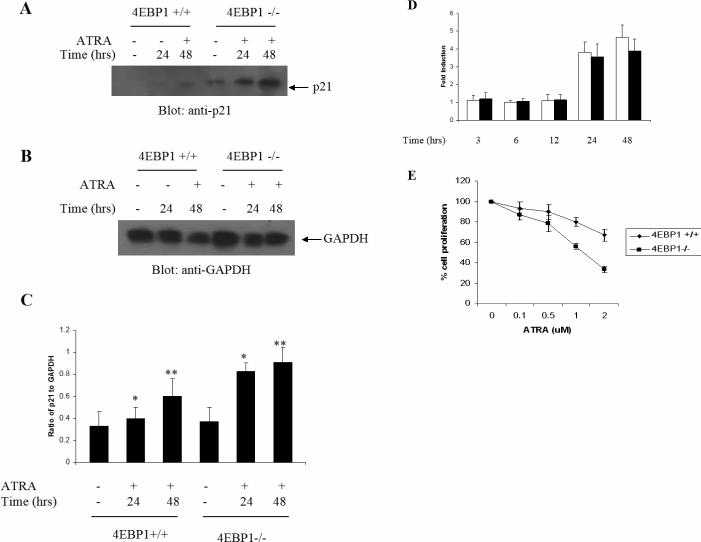

To directly examine the functional relevance of mTOR-mediated 4E-BP1 phosphorylation/de-activation in the generation of ATRA-responses, we used MEFs with targeted disruption of the 4e-bp1 gene (14). We examined the ATRA-dependent induction of expression of p21Waf1/Cip1 protein, a CDK inhibitor (19) that plays key role in the antiproliferative effects of ATRA (9-12,20-22). ATRA-treatment of 4E-BP1+/+ MEFs resulted in induction of p21 protein-expression, seen after 24−48 hours of treatment (Fig. 2A-C). However, such induction was strongly enhanced in cells lacking 4E-BP1 (Fig. 2A-C). On the other hand, when the ATRA-dependent induction of transcription of the p21Waf1/Cip1 gene was compared in 4E-BP1 +/+ and 4E-BP1 −/− MEFs, there were no significant differences between wild type MEFs and 4E-BP1 knockout MEFs (Fig. 2D). Thus, in the absence of 4E-BP1, there is enhanced p21Waf1/Cip1 protein-expression, but no differences in the transcriptional regulation of the p21Waf1/Cip1 gene.

Figure 2.

Targeted disruption of 4e-bp1 gene promotes ATRA-dependent p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression and generation of growth inhibitory responses. A. 4E-BP1 +/+ and 4E-BP1 −/− cells were treated with ATRA (1 μM) for the indicated times. Equal amounts of protein were immunoblotted with an anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 antibody. B. The blot shown in A was stripped and re-probed with an anti-GAPDH antibody. C. The signals for the different bands were quantitated by densitometry. Data are expressed as ratios of p21-protein to GAPDH levels and represent means ± SE of 4 independent experiments. Paired t-test analysis for p21 expression in 4EBP1+/+ versus 4EBP1−/− cells showed a p value=0.04 at 24 hours and p=0.0005 at 48hours. D. 4E-BP1+/+ and 4E-BP1−/− MEFs were treated with ATRA as indicated. Expression of mRNA for the p21 gene was evaluated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, using GAPDH for normalization. Data are expressed as fold increase over control DMSO-treated cells. Open bars indicate 4E-BP1+/+ MEFs and dark bars indicate 4E-BP1−/− MEFs. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. of 3 independent-experiments. E. 4E-BP1 +/+ and 4E-BP1 −/− MEF cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of ATRA for 5 days. Cell-proliferation was assessed by MTT assays. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. of 6 independent experiments.

To determine whether differential expression of p21Waf1/Cip1-protein has functional consequences in the generation of ATRA-responses, the induction of growth inhibitory effects was compared in 4E-BP1+/+ and 4E-BP1−/− MEFs. As expected, very low concentrations of ATRA (0.1 to 0.5 μM) did not induce inhibitory responses in either wild-type or 4E-BP1-knockout MEFs (Fig. 2E). However, at higher concentrations (1 to 2 μM), there were differences between wild-type and knockout MEFs, with 4E-BP1 −/− MEFs being clearly more sensitive to ATRA-dependent growth inhibition (Fig. 2E). Thus, enhanced p21 expression in the absence of 4E-BP1 correlates with enhanced generation of ATRA-dependent antiproliferative responses.

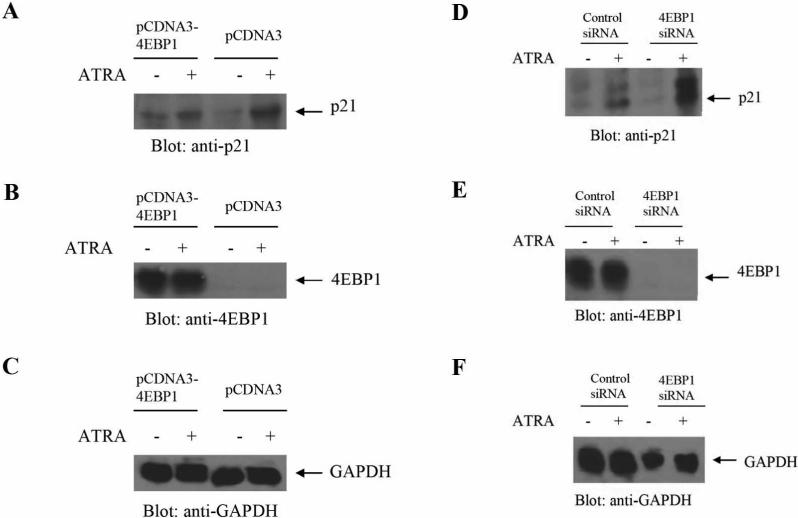

In other experiments, we determined whether ectopic 4E-BP1 re-expression in knockout MEFs suppresses p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression. We found that such expression was decreased in 4E-BP1-knockout MEFs transiently transfected with a pCDNA3-4e-bp1 construct, as compared to cells transfected with pCDNA3 empty-vector (Fig. 3A, B, C), further establishing that 4E-BP1 plays a negative regulatory role on ATRA-dependent expression of p21Waf1/Cip1. We also examined whether the regulatory effects of 4E-BP1 on p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression occur in cells of APL-origin. For this purpose, siRNA interference was used to knockdown 4E-BP1 in NB4 cells. Cells were transfected with a 4E-BP1-specific siRNA mix or control siRNAs, and treated with ATRA, prior to lysis and immunoblotting with an anti- p21Waf1/Cip1 antibody. Consistent with the experiments using 4E-BP1 knockout MEFs, knockdown of 4E-BP1 in this APL-derived cell line resulted in dramatic enhancement of ATRA-dependent expression of p21Waf1/Cip1 (Fig. 3D, E, F), suggesting that 4E-BP1 plays an important regulatory role in p21Waf1/Cip1mRNA-translation in APL cells.

Figure 3.

ATRA-induced p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression is 4E-BP1-dependent. A. 4EBP1−/− MEFs were transfected with pCDNA3−4E-BP1 or control empty vector and then treated with ATRA for 48 hours, as indicated. Equal amounts of protein lysates were immunoblotted with anti- p21Waf1/Cip1. B-C. Equal amounts of protein lysates from the experiment shown in A were analyzed separately by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti- 4E-BP1 (B) or anti-GAPDH (C) antibodies. D. NB4 cells were transfected with control siRNA or 4E-BP1-specific siRNA and treated with ATRA for ninety six hours, as indicated. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 antibody. E-F. Equal amounts of protein lysates from the same experiment were analyzed separately by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-4E-BP1 (E) or anti-GAPDH (F).

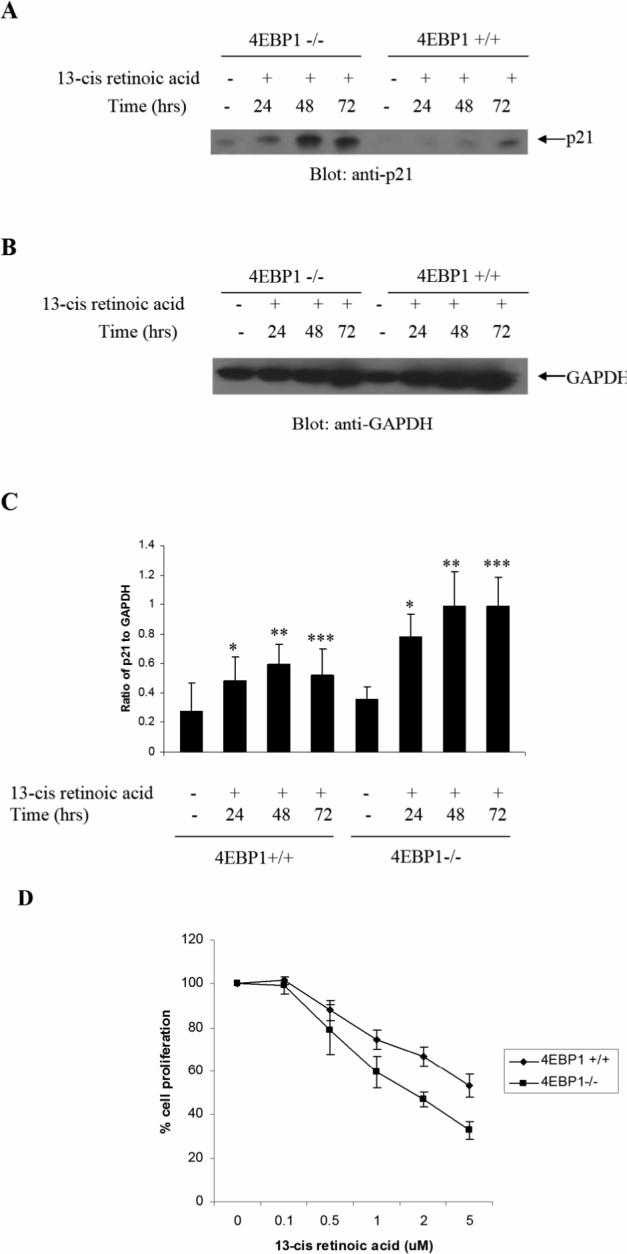

Finally, we examined whether 4E-BP1 is a common signaling element in all-trans- versus cis-retinoid signaling. When 4E-BP1−/− and 4E-BP1+/+ cells were analyzed in parallel, 13-cis-RA-dependent induction of p21WAF1 was found to be strongly enhanced in 4E-BP1 knockout MEFs (Fig. 4A-C). Moreover, 13-cis-RA-mediated anti-proliferative responses were enhanced in the absence of 4E-BP1 (Fig. 4D). Thus, as in the case of ATRA, targeted disruption of 4e-bp1 gene enhances generation of the effects of cis-RA, indicating that this repressor of mRNA-translation is a common element in the signaling pathways of different retinoids.

Figure 4.

Targeted disruption of 4e-bp1 gene promotes 13-cis-RA-dependent p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression and generation of growth inhibitory responses. A-B. 4E-BP1 +/+ and 4E-BP1 −/−cells were treated with 13-cis-RA as indicated. Equal amounts of protein were immunoblotted with anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 (A) or anti-GAPDH (B) antibodies. C. The signals were quantitated by densitometry. Data are expressed ratios of p21 to GAPDH levels and represent the means ± SE of 2 independent experiments. D. 4E-BP1 +/+ and 4E-BP1 −/− MEF cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of 13-cis-RA for 5 days. Cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assays. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. of 4 independent experiments.

Discussion

Extensive work over the years has led to a detailed understanding of the mechanisms by which retinoids regulate transcription of genes for the ultimate generation of protein-products that mediate their effects. This includes binding of retinoids to specific nuclear-receptors, which in turn regulate transcription of target-genes via interaction with specific promoter-elements (6,7). There is also accumulating evidence that beyond activation of classic retinoid-pathways, several other signaling cascades are engaged during RA-dependent cell-differentiation and/or growth inhibition. Such pathways involve Map-kinases (17,23-27), src-kinases (28), CrkL and Vav proteins (29-31), PKCγ (16) and PKA (32). Other signaling events implicated in the generation of retinoid-effects include modulation of histone-acetylation (33), suppression of AP-1 activity (34), and regulation of Stat1-phosphorylation (35). In addition, there is evidence implicating the PI 3'K/Akt signaling pathway in retinoid-dependent cell-differentiation (36,37). Thus, multiple signals are induced in response to treatment of cells with retinoids to regulate generation of specific biological responses.

mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase that is activated downstream of PI 3'K /Akt, and exhibits important regulatory effects on cell growth, cell cycle progression, and survival (38,39). It is now established that at least two distinct cellular pathways that regulate mRNA translation are activated downstream of mTOR. One major pathway involves activation of p70S6K and downstream engagement of the S6-ribosomal protein and eIF4B (38,39). The other pathway of critical importance in the initiation of cap-dependent mRNA translation involves phosphorylation of multiple sites in the translational repressor 4E-BP1, followed by de-activation of the protein and dissociation from eIF4E (38,39). In the present study, we directly assessed the role of 4E-BP1 in the generation of retinoid-responses. We were able to demonstrate that in response to ATRA, 4E-BP1 dissociates from eIF4E, allowing the formation of eIF4E-eIF4G complexes. Using cells from 4E-BP1 knockout mice, we found that all-trans- or cis-retinoic acid-dependent p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression is enhanced in cells lacking 4E-BP1. On the other hand, there are no differences in transcriptional-regulation of the protein between 4E-BP1 +/+ and −/− cells, consistent with other work from our group that has shown that rapamycin does not effect RARE-driven transcription (8). As p21Waf1/Cip1 has been implicated in the generation of the growth inhibitory effects of retinoids in different cell types, our findings provide evidence for a mechanism by which mTOR-signals may promote retinoid-responses. Such a mechanism appears to involve ATRA- or cis-RA-dependent de-activation of 4E-BP1, allowing initiation of mRNA-translation for p21Waf1/Cip1, and possibly other RA-regulated genes, involved in suppression of cell growth.

Our data are of considerable interest as, beyond implicating 4E-BP1 as a key regulator of ATRA-signaling, they suggest that the mTOR pathway can, under certain circumstances, mediate growth inhibitory signals. This pathway is activated in response to various mitogens and growth factors and it is generally viewed as a pathway that promotes cell-proliferation and survival (38,39). In fact, as aberrant cap-dependent translation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of certain malignancies, there are ongoing efforts to develop clinical-translational therapeutic approaches targeting mTOR for the treatment of cancer (40-42). However, there is also recent evidence that, under certain circumstances, the mTOR pathway can be activated by growth inhibitory cytokines such as interferons (15), to mediate diverse responses such as antiviral activities (15), and even pro-apoptotic effects (43). Our finding that ATRA- and cisRA-inducible upregulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 protein-expression is regulated by mTOR-mediated inhibition of 4E-BP1 activity, provides direct evidence that this pathway can be utilized by different ligands, to generate diverse biological responses.

p21Waf1/Cip1 plays important roles in cell-cycle progression via effects on CDK (44), while under certain circumstances, it also promotes cell survival (45,46). Although the role of cap-dependent mRNA translation in p21Waf1/Cip1-expression is not well-defined, there is some evidence that rapamycin blocks p21Waf1/Cip1-expression in response to thrombopoietin (47), EGF (48) and chemotherapeutic agents (49). Our findings demonstrate that this pathway also mediates retinoid-dependent upregulation of p21Waf1/Cip1, and for the first time identify a mechanism by which mTOR regulates such expression, involving de-activation of 4E-BP1. Although the involvement of additional components of the mTOR pathway in the regulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 remains to be determined, our findings suggest that 4E-BP1 plays an important regulatory role in the generation of retinoid- responses.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Merit grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs and NIH grants CA77816, CA100579, CA121192 (to LCP) and CA105005 and CA78282 (to DVK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tallman MS, Nabhan C, Feusner JH, Rowe JM. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2002;99:759–767. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang ME, Ye YC, hen SRC, Chai JR, Lu JX, Zhao L, Gu LJ, Wang ZY. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1988;72:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castaigne S, Chomienne C, Daniel MT, Ballerini P, Berger R, Fenaux P, Degos L. All-trans retinoic acid as a differentiation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. I. Clinical results. Blood. 1990;76:1704–1709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tallman MS. Differentiating therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:1262–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kambhampati S, Verma A, Li Y, Parmar S, Sassano A, Platanias LC. Signalling pathways activated by all-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells, Leuk. Lymphoma. 2004;45:2175–2185. doi: 10.1080/10428190410001722053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melnick A, icht JDL. Deconstructing a disease: RARalpha, its fusion partners, and their roles in the pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;93:3167–3215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambon P. The retinoid signaling pathway: molecular and genetic analyses. Semin. Cell Biol. 1994;5:115–125. doi: 10.1006/scel.1994.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lal L, Li Y, Smith J, Sassano A, Uddin, Parmar S, Tallman MS, Minucci S, Hay N, Platanias LC. Activation of the p70 S6K by all-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2005;105:1669–1677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang H, Lin J, Su ZZ, Collart FR, Huberman E, Fisher PB. Induction of differentiation in human promyelocytic HL-60 leukemia cells activates p21, WAF1/CIP1, expression in the absence of p53. Oncogene. 1994;9:3397–3406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casini T, Pelicci PG. A function of p21 during promyelocytic leukemia cell differentiation independent of CDK inhibition and cell cycle arrest. Oncogene. 1999;18:3235–3243. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YH, Lavelle D, DeSimone J, Uddin S, Platanias LC, Hankewych M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors increase p21(WAF1) and induce apoptosis of human myeloma cell lines independent of decreased IL-6 receptor expression. Blood. 1999;94:251–259. doi: 10.1002/ajh.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu SL, Chen MC, Chou YH, Hwang GY, Yin SC. Induction of p21(CIP1/Waf1) and activation of p34(cdc2) involved in retinoic acid-induced apoptosis in human hepatoma Hep3B cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;248:87–96. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fanelli M, Minucci S, Gelmetti V, Nervi C, Cambacorti-Passerini C, Pelicci G. Constitutive degradation of PML/RARalpha through the proteasome pathway mediates retinoic acid resistance. Blood. 1999;93:1477–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Poulin F, Kohara M, DeMaria CT, Cheng A, Wu Z, Gingras AC, Katsume A, Elchebly M, Spiegelman BM, Harper ME, Tremblay ML, Sonenberg N. Adipose tissue reduction in mice lacking the translational inhibitor 4E-BP1. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur S, Lal L, Sassano A, Majchrzak-Kita B, Srikanth M, aker DPB, Petroulakis E, Hay N, Sonenberg N, N., Fish EN, Platanias LC. Regulatory effects of mammalian target of rapamycin-activated pathways in type I and II interferon signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:1757–1768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kambhampati S, Verma A, Li Y, Sassano A, Majchrzak B, Deb DK, Parmar S, Giafis N, Kalvakolanu DV, Rahman A, Uddin S, Minucci S, Tallman M, Fish EN, Platanias LC. Activation of protein kinase C delta by all-trans-retinoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32544–32551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsayed Y, Uddin S, Mahmud N, Lekmine F, Kalvakolanu DV, Minucci S, Bokoch G, Platanias LC. Activation of Rac1 and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in response to all-trans-retinoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:4012–4019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sassano A, Katsoulidis E, Antico G, Altman JK, Redig AJ, Minucci S, Tallman MS, Platanias LC. Suppressive effects of statins on acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4524–4532. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss RH. p21Waf1/Cip1 as a therapeutic target in breast and other cancers. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggs JR, Kudlow JE, Kraft AS. The role of the transcription factor Sp1 in regulating the expression of the WAF1/CIP1 gene in U937 leukemic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:901–906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu M, Iavarone A, Freedman LP. Transcriptional activation of the human p21(WAF1/CIP1) gene by retinoic acid receptor. Correlation with retinoid induction of U937 cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31723–31728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otsuki T, Sakaguchi H, Hatayama T, Wu P, Takata A, Hyodoh F. Effects of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) on human myeloma cells. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2003;44:1651–1656. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000099652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milella M, Konopleva M, Precupanu CM, Tabe Y, Ricciardi MR, Gregorj C, Collins SJ, Carter BZ, D'Angelo C, Petrucci MT, Foa R, Cognetti F, Tafuri A, Reeff M. MEK blockade converts AML differentiating response to retinoids into extensive apoptosis. Blood. 2007;109:2121–2129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes PJ, Zhao Y, Chraratna RA, Brown GJ. Retinoid-mediated stimulation of steroid sulfatase activity in myeloid leukemic cell lines requires RARalpha and RXR and involves the phosphoinositide 3-kinase and ERK-MAP kinase pathways. Cell Biochem. 2006;97:327–350. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canon E, Cosgaya JM, Scsucova S, Ara A. Rapid effects of retinoic acid on CREB and ERK phosphorylation in neuronal cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:5583–5592. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.en AY, Roberson MS, Varvayanis S, Lee AT. Retinoic acid induced mitogen-activated protein (MAP)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase-dependent MAP kinase activation needed to elicit HL-60 cell differentiation and growth arrest. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3163–3172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gianni M, Parrella E, Raska I, Jr., Gaillard E, Nigro EA, Gaudon C, Garattini E, Rochette-Egly C. P38MAPK-dependent phosphorylation and degradation of SRC-3/AIB1 and RARalpha-mediated transcription. EMBO J. 2006;25:739–751. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katagiri K, Yokoyama KK, Yamamoto T, Omura S, Irie S, Katagiri T. Lyn and Fgr protein-tyrosine kinases prevent apoptosis during retinoic acid-induced granulocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:11557–11562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alsayed Y, Modi S, Uddin S, Mahmud N, Druker BJ, Fish EN, Hoffman R, Platanias LC. All-trans-retinoic acid induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the CrkL adapter in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Exp. Hematol. 2000;28:826–832. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guris DL, Duester G, Papaioannou VE, Imamoto A. Dose-dependent interaction of Tbx1 and Crkl and locally aberrant RA signaling in a model of del22q11 syndrome. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertagnolo V, Marchisio M, Brugnoli F, Bavelloni A, Boccafogli L, Colamussi ML, Capitani S. Requirement of tyrosine-phosphorylated Vav for morphological differentiation of all-trans-retinoic acid-treated HL-60 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Q, Tao J, Zhu Q, Jia PM, Dou AX, Li X, Cheng F, Waxman S, Chen GQ, Chen SJ, Lanotte M, Chen Z, Tong JH. Rapid induction of cAMP/PKA pathway during retinoic acid-induced acute promyelocytic leukemia cell differentiation. Leukemia. 2004;18:285–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagy L, Kao HY, Chakravarti D, Lin RJ, Hassig CA, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell. 1997;89:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin SC, Heyman RA, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimberg A, Karlberg I, Nilsson K, Oberg F. Ser727/Tyr701-phosphorylated Stat1 is required for the regulation of c-Myc, cyclins, and p27Kip1 associated with ATRA-induced G0/G1 arrest of U-937 cells. Blood. 2003;102:254–261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bastien J, Plassat JL, Payrastre B, Rochette-Egly C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway is essential for the retinoic acid-induced differentiation of F9 cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:2040–2047. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter CA. Retinoic acid signaling through PI 3-kinase induces differentiation of human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2003;75:34–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4800(03)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Gen. Development. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt, The two TORCs and Akt Dev. Cell. 2007;12:487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho D, Signoretti S, Regan M, Mier JW, Atkins MB. The role of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in the treatment of advanced renal cancer Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:758s–763s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pantuck AJ, Thomas G, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma: current status and future applications. Semin. Oncol. 2006;33:607–613. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Easton JB, Houghton PJ. mTOR and cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:6436–6446. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thyrell L, Hjortsberg L, Arulampalam V, Panaretakis T, Uhles S, Dagnell M, Zhivotovsky B, Leibiger I, Grer D, Pokrovskaja K. Interferon alpha-induced apoptosis in tumor cells is mediated through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24152–24162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asada M, Yamada T, Ichijo H, Delia D, Miyazono K, Fukumuro K, Mizutani S. Apoptosis inhibitory activity of cytoplasmic p21(Cip1/WAF1) in monocytic differentiation. EMBO. J. 1999;18:1223–1234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawlor MA, Rotwein P. Insulin-like growth factor-mediated muscle cell survival: central roles for Akt and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:8983–8995. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8983-8995.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raslova H, Baccini V, Loussaief L, Comba B, Larghero J, Debili N, Vainchenker W. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulates both proliferation of megakaryocyte progenitors and late stages of megakaryocyte differentiation. Blood. 2006;15:2303–2310. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ilyin GP, Glaise D, Gilot D, Baffet G, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Regulation and role of p21 and p27 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors during hepatocyte-differentiation and growth, Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G115–G127. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00309.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitsuuchi Y, Johnson SW, Selvakumaran M, Williams SJ, Hamilton TC, Testa JR. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signal transduction pathway plays a critical role in the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1 induced by cisplatin and paclitaxel. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5390–5394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]