Introduction

Research involving embodied conversational agents (ECAs) is not new (e.g., Bates, 1994; Koda & Maes, 1996; Rousseau & Hayes-Roth, 1997), but the application of ECAs outside research settings is relatively recent. ECAs are virtual characters rendered on a monitor or screen with whom a user converses. An ECA application commonly incorporates three components: a language processor, a behavior and planning engine, and a visualizer. The language processor accepts spoken, typed, or selected input from the user and maps this input to an underlying semantic representation (Cerrato & Ekeklint, 2002; Godéreaux, et al., 1996; Guinn & Hubal, 2003, 2004; Guinn & Montoya, 1998; Stokes, 2001; Wetter, & Nüse, 1992). The behavior engine accepts semantic content and other input from the user or system and determines ECA behaviors using cognitive, social, linguistic, physiological, planning, and other models (André, et al., 2000; Aylett, 2001; Bartneck, 2002; Elliott, 1993; Funge, Tu, & Terzopoulos, 1999; Kizakevich, et al., 1998; Magnenat-Thalmann & Kshirsagar, 2000; Norling & Ritter, 2004; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988; Prendinger & Ishizuka, 2001; Wray, et al., 2004; Xiao, Stasko, & Catrambone, 2002). These behaviors may include recomputation of sub-goal states; changes in emotional state; actions performed in the virtual environment; gestures, body movement, or facial expressions to be rendered; and spoken dialog. The visualizer renders the ECA and performs gesture, movement, and speech actions. In different applications, the user may be immersed in a virtual environment or may interact with an ECA rendered on a monitor with no appended devices.

A small sample of applications of ECAs includes:

Game-like learning environments (as animated pedagogical agents) (André, et al., 1999; Conati, 2002; Lester, et al., 1997; Moreno, et al., 2001; Moundridou & Virvou, 2002; Woods, et al., 2007);

Mission rehearsal training (to simulate conversation with civilians) (Hill, et al., 2003) and military leadership and cultural training (McCollum, et al., 2004; Raybourn, et al., 2005);

Tutoring of maintenance diagnostic skills (Guinn & Montoya, 1998; Rickel & Johnson, 1999);

Interrogation and de-escalation training for law enforcement (Frank, et al., 2002; Olsen, 2001);

Training in clinical interaction skills for medical personnel (Deterding, Milliron, & Hubal, 2005; Johnsen, et al., 2005; Kizakevich, et al., 2003);

Obtaining informed consent from research participants (Hubal & Day, 2006) and training interviewers in skills to avoid non-response during field interviews (Camburn, Gunther-Mohr, & Lessler, 1999; Link, et al., 2006);

Simulation of dialog with a substance abuse coach (Hayes-Roth, et al., 2004) or within therapeutic sessions for various phobias (Klinger, et al., 2005; Slater, Pertaub, & Steed, 1999; Takács, 2005).

The populations that have been studied using these applications include school-age children, soldiers, law enforcement officers, medical first responders, research participants, and patients in therapy. The studies presented in this paper add inner-city adolescents and prisoners to this list.

The studies presented in this paper also add to the understanding of accessibility, engagement, and usability of ECAs with varied populations. The populations studied here are generally underserved with technological advancements, despite the often intense study of their behavior, and despite no apparent barrier to their acceptance of technological interventions. Researchers' interests often lie more in these populations' responses to interventions (often non-technological) and to social causes of their behavior. Meanwhile, technology researchers' interests, especially those regarding ECA accessibility and usability, are largely served by convenient populations such as elementary school or undergraduate students or even soldiers who represent “normal” users of the technology. Evaluators of ECA applications, however, are instructed to take into account data collection methods and even how to select the right participants (Christoph, 2004; Ruttkay, Dormann, & Noot, 2004). A true test of how generalizable and useful advanced technologies are to society relies on the study of varied populations.

This paper presents findings from two studies, one using ECA vignettes to assess propensity to risky behaviors in a population of at-risk adolescents, the other using a parallel set of ECA vignettes to assess the same in a prison setting. Each study involved an intervention to instill in participants an understanding of appropriate social skills. Assessment of these behaviors is usually based on self-ratings, external ratings, and archival records, all of which are limited in a number of ways. Self-ratings may be biased by poor recall and social desirability, while external ratings (e.g., by teachers, parents, or counselors) may be based on limited observation of behavior and/or stereotyping bias (Frankfort-Nachmias & Nachmias, 2000). Similarly, archival records (e.g., of disciplinary actions) may fail to capture behaviors that reflect poor social competency skills. Although some interventions include role play exercises that may be used to gauge social competency skills, they may be difficult to implement with a large number of participants or in many settings. These limitations point to the need for novel measures of social competency that can be administered relatively easily, simulate real interactions with other people, and be used to evaluate prevention programs.

For each of the two studies, the application, participants, and methods are described in some detail, as these details contribute to the understanding of study results regarding accessibility, engagement, and usability. The results are related to earlier findings. A general discussion section identifies implications for further research and development.

Study 1. Adolescents

Many adolescents are at risk of encountering social situations that require anger management, negotiation, or conflict-resolution skills. This is especially true for adolescents living in economically disadvantaged communities or dysfunctional families, where they are often confronted with potentially harmful social situations and may not have adequate social skills to handle those situations constructively. To avoid adverse consequences (such as violence, drug use, risky sexual behavior, school suspension), adolescents must first learn these social skills and then gain the experience to apply them effectively. Developing cost-effective approaches to assessing and improving adolescents' decision-making and social competency skills is an ongoing challenge for prevention researchers and practitioners (Botvin, et al., 1995; Gottfredson & Wilson, 2003; Jessor, 1998). Impairments in executive cognitive functioning (ECF), a higher-order subset of neuropsychological abilities, have been implicated in aggression and are thought to be responsible for poor social skills and decision-making ability, insensitivity to punishment, impulsivity, and inability to regulate emotional responses (Dawes, et al., 2000; Fishbein, Hyde, et al., 2006). ECF and emotional deficits contribute to traits often cited as precursors of antisocial behavior, most notably early and persistent aggression, psychopathy, substance abuse, conduct disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Fishbein, 2000; Giancola, et al., 1996, 1998; Paschall & Fishbein, 2001; Tarter, et al., 1999).

Research suggests that social skills simulation may be an effective approach to both assessing adolescents' risk for adverse consequences and training them to reduce that risk (Bosworth, et al., 2000; Cho, et al., 2000; Margalit, 1989). Research also suggests that role playing is an effective means of providing adolescents with anger management and other social competency skills (Hammond & Yung, 1991; Yung & Hammond, 1998). ECA simulation has been proposed as a cost-effective means of assessing and improving a broad range of technical and social competencies and skills (Hubal & Frank, 2001; Kizakevich, et al., 1998) that might be particularly attractive to at-risk adolescent populations.

ECA technology enables users to engage in natural conversation with the agents. ECAs are designed to understand, respond verbally, and react appropriately to the individual being trained or assessed. Because ECAs can simulate evolving social situations, they make possible much more realistic encounters than less interactive paper-based or less dynamic video-based social skills training. ECA simulations also avoid some ethical or legal issues surrounding provocative role playing encounters. For instance, researchers cannot ethically place adolescents in a risky situation intentionally, even after providing training in skills to manage that situation. Nor can researchers follow adolescents through their lives hoping that risky situations arise and provide an opportunity to assess intervention skills.

This study focused on a decision-making and social competency skills assessment targeted by an ECA tool for high-risk adolescents. The study examined neurocognitive-emotive predictors of behavioral problems among minority adolescents in high-risk urban settings and identified promising approaches to improve social-cognitive skills and reduce problem behaviors such as interpersonal violence and drug abuse. The lack of certain decision-making and social competency skills has been associated with violent behavior and drug use, and as a result, those skills have been targeted by many adolescent violence and drug abuse prevention programs. The ECA application was based on those skills, which include emotional control, information seeking, expressing one's own preferences, negotiation and willingness to compromise, and using non-provocative language. The skills were assessed by simulating real social encounters -- in a safe setting -- that may have adverse consequences.

Previous research demonstrated that questionnaire vignettes representing hypothetical social situations can discriminate between adolescents at high and low risk for violent behavior (e.g., Paschall & Flewelling, 1997; Guerra & Slaby, 1990; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). Vignettes used in those studies asked adolescents what they would do in potentially provocative social situations, with possible response options corresponding to decision-making and social competencies such as information seeking. The studies found that adolescents with a history of violent behavior were more likely to choose verbally or physically aggressive responses than adolescents without a history of violence. A number of intervention studies also indicate that improvement of these competencies reduces urban minority adolescents' risk for violent behavior and drug use (e.g., Botvin, et al., 1995; Guerra & Slaby, 1990; Hammond & Yung, 1991).

This study extended previous research by using ECA technology and hypothetical social situations (termed virtual vignettes) to develop a decision-making and social competency skills assessment and training tool for high-risk adolescents. An ECA representing a teenager of the same gender (male) and similar ethnicity to the study participant, was created to simulate provocative interpersonal social situations in a school setting. Using a Wizard-of-Oz technique (Dahlbäck, Jönsson, & Ahrenberg, 1993), a hidden observer immediately categorized the adolescents' responses to the ECA according to the criteria shown in Table 1. The responses of the ECA were then controlled not by the observer but by the behavior models underlying the ECA simulation, based on the category entered by the observer.

Table 1.

Categories for Coding Participants' Responses

| Category (keypress by observer) | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 = yes | something affirmative indicating participant will do what virtual character is asking him to do |

| 2 = request for more information | wants to know why virtual character is angry or feels provoked; wants to know more about situation; wants to know what's in the bag, why virtual character can't keep it himself, etc. |

| 3 = request for greater reward | wants more money; wants money more quickly; wants something else in return |

| 4 = ambivalence | not interested; could take it or leave it; doesn't know; doesn't care; wants to be left alone; has to think about it |

| 5 = negotiation or bargaining | tries to get virtual character not to beat him up; wants to know what he can do to make it up to virtual character, etc.; wants to change the plan and offers another plan; wants to keep the goods or be part of the action |

| 6 = oppositional | negative, provocative, angry, etc. |

| 9 = no | something to indicate that he won't do it |

Methods

Participants

The participants were African-American male adolescents in 10th grade who were already participating in a much larger ongoing longitudinal epidemiological prevention study (Kellam, et al., 1998). A purposive 125-person sample of adolescents, mean age 15.7 years, was selected for this study; half had a diagnosis of conduct disorder by either parent or self and half did not have a diagnosis of conduct disorder or other external rating of behavioral misconduct. This purposive sampling strategy was used to ensure adequate variation in behavioral problems and related psychosocial factors and to assess psychometric properties of the virtual vignette performance measures. All of the participants were living in low-income, inner-city neighborhoods.

Materials

Positive Adolescent Choices Training (PACT)

PACT (Yung & Hammond, 1995) is a promising violence prevention program developed for adolescents who are exposed to violence in their communities, families, and schools or who have exhibited a propensity for violent behavior, to improve their anger management and social-cognitive (i.e., negotiation and conflict-resolution) skills. The present study evaluated a key component of the PACT program, the Workin' It Out videotape, which trains adolescents in negotiation and conflict-resolution skills. The study focused on medium-term effects of the videotape on adolescents' negotiation and conflict-resolution skills and used a global measure of cognitive ability (IQ) as a covariate to isolate the effects of ECF on intervention response. Participants provided baseline data for targeted outcome measures (described below). Approximately two months later, half the participants (selected at random) were assigned to watch the Workin' It Out videotape under the supervision of a trained facilitator, who narrated and reinforced the content. Participants who watched the videotape were asked several structured questions by the facilitator during and after the videotape to ensure that they had been adequately exposed to the negotiation skills training information and character role playing presented in the videotape. Participants then completed a questionnaire on self expectations for behavior and decisions in specific risk scenarios; these were used as targeted outcome measures.

Virtual Vignettes

The virtual vignettes were developed to simulate interpersonal verbal interactions with appropriate body language (Hubal, Frank, & Guinn, 2003). Portraying realistic ECAs -- that is, full-body, animated, conversant agents with whom the participant interacts that exhibit emotional, social, gestural, and cognitive intelligence -- requires modeling a clearly defined emotional state, actions that show thought processes, and accentuation that reveals feelings. To use ECA technology for assessment, the participant must be able to engage with ECAs that use gaze, gesture, intonation, and body posture, as well as verbal feedback, during the interaction.

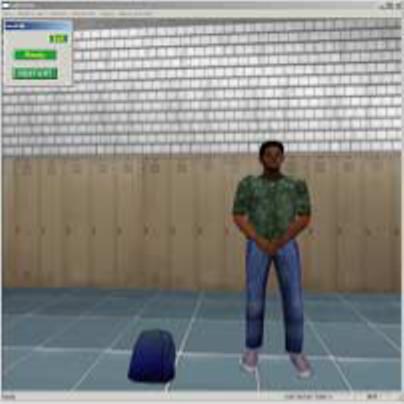

Based on the content of role plays in the PACT program, scripts were developed for the ECA in a school hallway (shown in Figure 1) to entice study participants to engage in risky decision-making, and exhibit impulsive behavior and insensitivity to penalties. The scripts, which were vetted by a group of adolescents not participating in this study, included provocative introductory statements and multiple response options for the participant.

Figure 1.

ECA Used in Adolescent Application

Three vignettes were developed. In one vignette, the ECA asked the study participant to keep a gym bag containing unknown goods in his school locker, but did not provide any information about what was in the gym bag. If the participant refused, the ECA offered money and insisted that the participant owed him a favor. If the participant asked what was in the bag, he found out that it contained stolen goods (a pair of stolen sneakers or a stolen wallet). Study participants thus had the opportunity to practice PACT principles in seeking information and then using refusal and negotiation skills to resolve the situation. In a second vignette, the ECA invited the participant to join in a known prohibited activity (a drinking party with girls and no adult supervision or a joyride in a car). In a third vignette, the ECA initiated a confrontation (accusing the participant of bumping into him in the hallway or of messing with his girlfriend) and tried to provoke a fight.

Consistent with the PACT principles, responses were placed in categories that indicated change, or lack thereof, in decision-making skills from baseline to post-exposure to the intervention. Based on the PACT teaching objectives, the participants' verbal responses were categorized as seeking information, compromise or negotiation, ambivalence, opposition or negation, and statements expressing the participant's position or preference. Examples of how participant input was categorized using these decision-making and social competency skills are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Categorization of a Sample of Participant Responses within Virtual Vignettes

| Sample ECA statement | Participant response | Response categorization |

|---|---|---|

| Vignette: Stolen goods | ||

| Can you put this bag in your locker / cell for me? | Query: What is it? | Seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| Can you put this bag in your locker / cell for me? | Query: What's in it for me? | Willing to compromise or negotiate; not regulating emotions; seeking information |

| Can you put this bag in your locker / cell for me? | Query: Why can't you use your own locker / keep it yourself? | Additional refusal; being less agreeable; willing to compromise or negotiate; seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| The COs are shaking us down today. | Statement: I don't think that's a good idea. | Additional refusal |

| It's just something I got from someone else. | Query: Like I said, what is it? | Willing to compromise or negotiate; seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| No one's going to find out. | Query: Like I said, what is it? | Willing to compromise or negotiate; seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| Here's a deal, I'll give you $25 later this afternoon for your efforts. | Query: Where will you get the money? | Seeking information |

| Here's a deal, I'll give you $25 later this afternoon for your efforts. | Request: How about $50? | On the edge of agreeing or refusing; willing to compromise or negotiate; seeking information |

| I can give you fifty bucks this weekend if you keep this for me. | Demand: Give me the money now. | Being less agreeable; willing to compromise or negotiate; not regulating emotions; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| Vignette: Party / Car ride | ||

| I got some ladies lined up for us tonight at my place, they want to play some drinking games. The girls are going to bring some booze, so all we got to do is order some pizza and crank up the jams. | Query: What drinks will there be? | Seeking information |

| Query: What kind of vehicle? | ||

| I got the keys to my mom's car tonight and I'm thinking of going for a little joy ride. The car's pretty nice, so all we got to do is climb aboard and crank up the jams. | ||

| I got some ladies lined up for us tonight at my place, they want to play some drinking games. the girls are going to bring some booze, so all we got to do is order some pizza and crank up the jams. | Query: What games are there going to be? | Getting more involved within the situation; seeking information |

| Query: Where are we riding? | ||

| I got the keys to my mom's car tonight and I'm thinking of going for a little joy ride. The car's pretty nice, so all we got to do is climb aboard and crank up the jams. | ||

| I got some ladies lined up for us tonight at my place, they want to play some drinking games. the girls are going to bring some booze, so all we got to do is order some pizza and crank up the jams. | Query: Who's going to have to get the food / fuel? | Seeking information; getting more involved within the situation; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| I got the keys to my mom's car tonight and I'm thinking of going for a little joy ride. The car's pretty nice, so all we got to do is climb aboard and crank up the jams. | ||

| You don't know these girls, they live across town. I think they're bored hanging out with the same old people and they want to meet some new people. These girls are fun, and let me tell you good looking, I know you're going to like them. | Query: Who are the girls / What kind of ride? | Willing to compromise or negotiate; seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| I don't think you've ever seen the car, my mom just bought it. I took the keys from her purse this morning. I'm thinking it drives pretty nice on the highway and I got to test it out. It's going to be fun and let me tell you pretty fast, I know you're going to like it. | ||

| Oh come on man. Do it for me, just one night is all I'm asking. | Statement: I'll hang with you but won't drink / ride. | On the edge of agreeing or refusing; being agreeable; willing to compromise or negotiate; seeking information |

| Aw, come on and have some fun. Why you acting like that? | Statement: I'm worried about my parents / the parole officer finding out. | Being less agreeable; willing to compromise or negotiate; getting more involved within the situation; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| I got some ladies lined up for us tonight at my place, they want to play some drinking games. the girls are going to bring some booze, so all we got to do is order some pizza and crank up the jams. | Statement: Sorry, I have other plans. | Additional refusal; willing to compromise or negotiate; detaching from the situation; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| I got the keys to my mom's car tonight and I'm thinking of going for a little joy ride. The car's pretty nice, so all we got to do is climb aboard and crank up the jams. | ||

| No one's going to find out. | Statement: Sorry, I have other plans. | Additional refusal; willing to compromise or negotiate; detaching from the situation; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| Vignette: Confrontation | ||

| I know you don't want to be starting something with me. | Statement: I didn't do anything. | Being less agreeable; detaching from the situation; regulating emotions; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| I know you don't want to be starting something with me. | Demand: What are you going to do about it? | Being less agreeable; unwilling to compromise or negotiate; getting more involved within the situation; not regulating emotions; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| Oh, now you going to try to act like you didn't do nothing. You know I'll kick your ass if you try something. | Statement: I said I'm sorry. | Additional refusal; being agreeable; willing to compromise or negotiate; regulating emotions; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| Yeah, you just need to say sorry. | Statement: I said I'm sorry. | Additional refusal; being agreeable; willing to compromise or negotiate; regulating emotions; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| You better watch your mouth or you got something coming from me! | Query: What are you so upset about? | Regulating emotions; seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| You don't want to embarrass yourself in front of your people! | Statement: I didn't do anything. | Being less agreeable; detaching from the situation; regulating emotions; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| You getting smart? I don't take that from nobody | Demand: Let's take this outside. | Unwilling to compromise or negotiate; getting more involved within the situation; not regulating emotions |

| All vignettes | ||

| (various) | Statement: I doubt it. | Willing to compromise or negotiate; detaching from the situation; seeking information; verbalizing feelings / intentions |

| (various) | Statement: No. | Additional refusal |

| (various) | Statement: Not sure. | Detaching from the situation |

| (various) | Statement: Probably. | Additional positive response; being agreeable |

| (various) | Statement: Yes. | Being agreeable; less willing to verbalize feelings / intentions |

An algorithm was developed by which the ECA would initially entice the risky behavior but gradually back off if the participant demonstrated appropriate avoidance or de-escalation behavior (i.e., information seeking, negotiation). The algorithm took into account how long the interaction had been going on, how insistent the participant was in refusing to be enticed by the ECA, and the content of the conversation. Specifically, the algorithm would end the conversation only if:

It has been a long conversation (number of turns >= 7) and the participant has refused the ECA at least once; or

It has been an acceptably long conversation (number of turns >= 5) and the participant has refused the ECA twice or refused at least once and hedged at least once; or

It has been a pretty short conversation so far (number of turns >= 3) but the participant has refused the ECA three times or refused at least twice and hedged at least once.

In this study, the participant conversed naturally with the ECA. That is, each participant was instructed to respond to the ECA as if he was in a real-life situation, so the participant spoke directly to the ECA and listened to its response. However, the natural language component of the architecture (see Guinn & Montoya, 1998) was turned off. Instead, behind the participant, an experimental observer immediately categorized the participant's responses into one of a set of potential responses (see Table 1), and this categorization was fed to the ECA. Specifically, the observer pressed a key representing the category, and the following sequence of events occurred in the ECA program:

Variable values were updated to reflect the participant's use of or failure to use social skills that may have been learned in the PACT intervention (e.g., expressing preferences, seeking information; see the last column of Table 2).

The ECA interpreted the input as an utterance. If by this utterance the participant had not yet reached an end-point to the conversation (as determined by the algorithm above), state variables and transitions determined the next response of the ECA, to include spoken output and any appropriate gestures or movements. (For details on the state transition network architecture, see Hubal, et al., 2003.)

Thus, the observer was responsible for categorizing the participant's utterance but otherwise did not influence the behavior of the ECA.

The language of the ECA was modeled on that used by adolescents in the study sample, although computer-generated speech was used for the present study. The ECA remained in one position because the entire interaction is based primarily on conversation, so the gestures were not complex, relying mostly on beat gestures and idle motions (Cassell, et al., 2000). However, as the ECA became more agitated or aggressive, the gestures became more representational (e.g., pointing, placing the hands on hips), depending on the content of the conversation.

Two versions of each of the three vignettes (stolen goods, party/car ride, and confrontation) were developed for the study. One set of three was presented to participants before any prevention materials were presented (for those participants in the experimental group), and one set was presented after. Each vignette could run for a maximum of 10 to 12 conversational turns, but only if the participant sought all the information that the ECA could provide. More detail about the development and content of the virtual vignettes is provided elsewhere (Paschall, et al., 2005).

Procedure

Before the virtual vignette exercises began, study participants were told that they would be interacting with a teenage character on the computer and that they should behave just as they would in a real-life situation in school or on the street. Participants were led to believe that the ECA could hear them and would respond directly to their utterances; they were shown the speakers on the computer and told to speak clearly into them so the ECA could understand them. They were also told that there were no right or wrong ways to respond to the ECA. At the beginning of the first exercise, the ECA introduced himself as Greg and asked the study participant his name and the time, providing participants with some practice and familiarization prior to the actual exercises. Participants were also encouraged to ask the facilitator what Greg said if for some reason they were unable to understand him.

All of the virtual vignette exercises and data collection activities were carried out separately for each adolescent participating in the study during baseline and post-intervention sessions.

Measures

Vignette Performance

Two measures of social competency and conflict-resolution skills were included in baseline and follow-up data collection. One was based on participants' responses to questions about hypothetical confrontational situations in a written questionnaire, the other was based on observation of participants' interaction with the ECA in the virtual vignette task.

Four vignettes were presented in the questionnaire to measure participants' conflict-resolution style (see Slaby & Wilson-Brewer, 1992). Participants were presented with a hypothetical confrontational situation, and then asked what they would probably do in that situation (e.g., “Imagine you're in line for a drink of water. Another kid comes up and pushes you out of line. What would you do?”). For each vignette, participants were presented with verbally aggressive, information seeking, passive, and physically aggressive response options. A four-point response scale was created, as follows: neither a verbally nor a physically aggressive response was chosen (1 point); a verbally aggressive response was chosen, but not a physically aggressive response (2 points); a physically aggressive response was chosen, but not a verbally aggressive response (3 points); or both verbally and physically aggressive responses were chosen (4 points). A mean response score was computed for each participant with a higher score indicating a more aggressive conflict-resolution style.

Measures of decision-making and social competency skills, such as information seeking and negotiation, were based on ratings of adolescents' verbal and nonverbal interaction with the ECA along seven dimensions: level of engagement, verbalization, emotional control, information seeking, expressing own preferences, compromise/negotiation, and being non-provocative (see Table 3). A five-point scale for each decision-making and social competency dimension ranged from very low to moderate to very high. Two trained researchers observed each adolescent's performance on three virtual vignette exercises and recorded their ratings on separate forms, yielding a total of 21 performance measures. The correspondence between the two raters' scoring for the five decision-making and social competency dimensions was very high (r = 0.94 to 0.99).

Table 3.

Virtual Vignette Performance Rating Criteria

| Performance Measure | Scoring | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement | Very Low | Participant doesn't seem to enjoy doing the vignettes, doesn't take ECA seriously. Seems to only be responding to ECA because he has to. May tell the experimenter, “I can't talk to a computer.” |

| Low | Participant is doing the vignettes, but not getting into them. | |

| Moderate | Participant doesn't seem to like/dislike doing the vignettes. | |

| High | Participant seems to like the vignettes and is engaged. May tell the experimenter he likes the vignettes. | |

| |

Very High |

Participant is extremely engaged in the vignette activity. May tell the experimenter the vignettes were awesome and that he wishes they were longer. |

| Verbalizations | Very Low | Two responses -- Participant responds by saying only yes/no. |

| Low | Three responses -- Participant says only a little more than yes/no. | |

| Moderate | Four short responses -- Participant doesn't go into too much detail when responding to ECA. | |

| High | Five responses -- Participant may have said yes or no, but also provided ECA with detailed information (e.g., questions, preferences, excuses). | |

| |

Very High |

Six responses -- Participant holds a conversation with ECA, providing him with information about preferences, lots of negotiation, perhaps even provocative statements. This participant never limits his responses to a simple yes/no and stands out from other participants because of how much he says. |

| Comprehension | Very Low | Has to ask four or more times for experimenter to repeat what ECA said or asks to restart the vignettes because he didn't understand ECA. |

| Low | May ask three times for the experimenter to repeat what ECA said. | |

| Moderate | May ask a couple of times for the experimenter to repeat what ECA said. | |

| High | Doesn't ask for experimenter to repeat what ECA said but may hesitate once or twice when responding to ECA in order to understand him. | |

| |

Very High |

No problems understanding what ECA said. |

| Reaction Time | Very Slow | Participant waits long enough that ECA may say multiple times, “Sorry, I didn't catch that man.” Participant may be told multiple times by the experimenter to respond to ECA. |

| Slow | Participant waits long enough that ECA may say once, “Sorry, I didn't catch that man.” | |

| Moderate | Participant hesitates for about five seconds and may be told once to respond to ECA. Participant seems to think about what he is going to say before responding. | |

| Fast | Participant responds to ECA within a couple of seconds. | |

| |

Very Fast |

Participant responds to ECA immediately and sometimes before ECA can finish his sentence. |

| Emotional Control | Very Low | Not calm at all, very emotional. |

| Low | Not too calm but was able to control emotions to a small degree. | |

| Moderate | Somewhat calm/emotional state went both ways. | |

| High | Calm/not too emotional. | |

| |

Very High |

Very calm/not emotional at all. |

| Information seeking | Very Low | Participant did not ask ECA any questions. |

| Low | One question asked. | |

| Moderate | Two questions asked. | |

| High | Three questions asked. | |

| |

Very High |

Four or more questions asked. |

| Providing information about own preferences | Very Low | Study participant says only “yes” or “no” to the ECA. |

| Low | Participant provides one reason why he doesn't wish to go along with ECA. | |

| Moderate | Participant provides two reasons why he doesn't wish to go along with ECA. | |

| High | Participant provides three reasons why he doesn't wish to go along with ECA. | |

| |

Very High |

Participant provides four or more reasons why he doesn't wish to go along with ECA. |

| Negotiation | Very Low | Study participants does not use any negotiation or bargaining statements (e.g., asking ECA what can be done to avoid a physical fight). |

| Low | One negotiation or bargaining statement. | |

| Moderate | Two negotiation or bargaining statements. | |

| High | Three negotiation or bargaining statements. | |

| |

Very High |

Four or more negotiation or bargaining statements. |

| Being non-provocative | Very Low | Four or more provocative or oppositional statements by study participant and/or study participant curses at the ECA multiple times. |

| Low | Three provocative/oppositional statements and/or study participant may curse at ECA one time. | |

| Moderate | One or two provocative/oppositional statements and study participant doesn't curse at ECA. | |

| High | No provocative/oppositional statements, but study participant's tone could be more calm. | |

| Very High | No provocative/oppositional statements and study participant is not provocative in any way. |

Other measures of each participant's social competency skills were also acquired: three psychosocial variables (beliefs supporting aggression, aggressive conflict-resolution style, and hostility), teacher behavioral ratings, and self-reported drug use. Finally, measures of participants' IQ, ECF (executive decision-making, impulsivity, vigilance, and delay of gratification), and emotional perception (facial recognition) were taken to determine the extent to which they predicted intervention response. (See Paschall, et al., 2005, for more details.)

Measurement Validity

Because this approach using ECA technology for assessment was untested, one goal of the study was to assess the psychometric properties of virtual vignette performance measures. Three types of validity -- factorial, construct, and criterion validity -- were assessed in this study.

Factorial validity was assessed through factor analysis to determine if measures that appear to be conceptually similar or different actually load on the same or different factors. Based on the content or face validity of virtual vignette performance measures, it was expected that exploratory factor analysis would yield a small number of multi-item constructs, focusing on adolescents' emotional control or composure and their verbal interaction with the ECA.

The construct validity of a novel measure is supported if the measure is associated with established measures of similar constructs measured at the same time. The study examined the associations between multi-item measures of decision-making and social competency skills derived through the exploratory factor analysis and multi-item measures of beliefs supporting aggression, aggressive conflict-resolution style, and hostility that have been shown to have adequate psychometric properties in other studies (Paschall & Flewelling, 1997; Paschall & Hubbard, 1998; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). The hypothesis was that the multi-item measures of decision-making and social competency skills would be inversely associated with the three established measures.

The criterion-related validity of a novel measure is supported if the measure is associated with other objective (criterion) measures of the same or similar constructs. The hypothesis was that the multi-item measures of decision-making and social competency skills would be inversely associated with teacher ratings of adolescents' personality traits and behavioral misconduct (e.g., conduct disorder, hyperactivity, impulsivity, aggression) and positively associated with adolescents' self-reports of drug use.

Results

Results of Validity Analyses

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was first conducted to assess the nature and number of independent latent constructs underlying the virtual vignette performance measures. An initial two-factor solution on the baseline data was obtained with 18 of the 21 performance measures; a more stringent later solution indicated that 12 of 18 performance measures loaded on two distinct factors representing emotional control and interpersonal communication skills (six items each). Measures of emotional control and being non-provocative from all three virtual vignette exercises loaded strongly on one factor, along with the negotiation measure from the confrontation vignette. This factor appeared to represent adolescents' emotional control or composure in a confrontational situation. Measures of engagement level, expressing own preferences, and verbalizations from all three exercises loaded on a second factor, along with information seeking and negotiation measures from the stolen goods vignette. This second factor appeared to represent adolescents' interpersonal communication skills in a generally non-confrontational situation. Information seeking measures from the other two exercises and the negotiation measure from the party/car ride vignette did not load strongly on a single factor and were dropped from further analyses. The internal reliability of the multi-item emotional control and interpersonal communication skills factor measures was very good (Cronbach alphas = 0.88 and 0.90, respectively). (For further analyses, see Paschall, et al., 2005.)

Construct and Criterion-Related Validity

The construct validity of multi-item measures derived through factor analysis was assessed by examining their associations with measures of beliefs supporting aggression, aggressive conflict-resolution style, and hostility. The criterion-related validity of the multi-item measures was gauged by examining their associations with measures of behavioral problems based on teacher ratings and adolescent self-reports of drug use. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients and t-tests were used for these analyses. The emotional control factor was inversely associated with all three psychosocial variables, but the interpersonal communication skills factor was not significantly associated with any of the psychosocial variables, though trends were noted. A similar pattern of results was observed for the criterion measures of behavioral problems based on teacher ratings, as the emotional control factor was inversely associated with almost all of these variables, while the interpersonal communication skills factor was not. (For details, see Paschall, et al., 2005.) Hence, the measures used by an observer while the participants interacted with an ECA within virtual vignettes appear to have some validity, supporting not only the use of these observational techniques but also the use of virtual vignettes themselves.

Results of Virtual Vignette Outcome Analyses

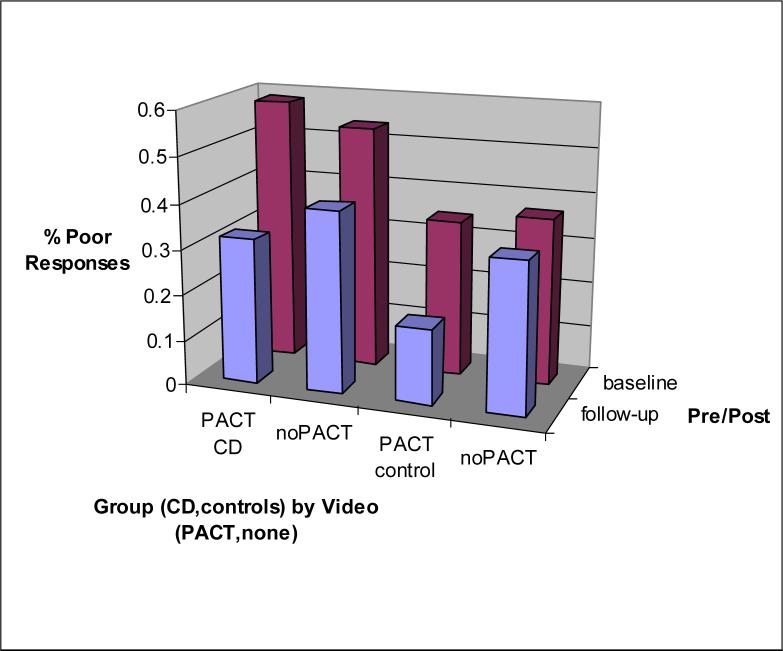

Data from experimental participants (30 adolescents diagnosed with conduct disorder, 30 without conduct disorder), as well as a matched control group of 65 participants (31 diagnosed with conduct disorder, 34 without conduct disorder) who were not presented with the PACT intervention, were further analyzed for the outcome from the vignettes (see Table 4 and Figure 2). The vignettes were sufficiently engaging that, during the interaction, a sizeable percentage of participants demonstrated potentially risky behavior, even after exposure to the preventive materials. For the group diagnosed with conduct disorder, on average, the participant agreed to help, go along with, or escalate a confrontation with the ECA (all risky behaviors) almost half (46%) the time. For the group not diagnosed with conduct disorder, the participant exhibited risky behavior not quite one-third (31%) of the time. These values are significantly different from zero. Furthermore, the two groups differed from each other (F(1,122) = 12.31, p < 0.001), suggesting that the vignettes were realistic enough to be able to discriminate between behavioral groups. Relatedly, there was an interaction between experimental group and change in behavior between baseline and post-intervention testing: participants who were exposed to the preventive materials were significantly more likely to use positive interaction skills during the post-intervention vignettes compared to baseline (exhibiting risky behavior 46% of the time baseline vs. 24% post-intervention) than those not exposed (45% baseline vs. 37% post-intervention) (F(1,118) = 4.69, p < 0.03), indicating some effectiveness not only of the intervention, but also of the vignettes as a valid assessment.

Table 4.

Analysis of Adolescent Responses to Vignettes

| Vignette | Immediate or Near-Immediate Refusal | Eventual Refusal | Immediate or Near-Immediate Acceptance or Escalation | Eventual Acceptance or Escalation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen goods | ||||||||||||

| Baseline (N = 125) | 18% | 31% | 30% | 20% | ||||||||

| 20% | 13% | 27% | 16% | 37% | 42% | 17% | 29% | |||||

| 20% | 21% | 40% | 41% | 17% | 26% | 23% | 12% | |||||

| Post-Intervention (N = 122) | 27% | 47% | 14% | 12% | ||||||||

| 13% | 45% | 53% | 29% | 10% | 19% | 23% | 6% | |||||

| 30% | 21% | 60% | 44% | 7% | 21% | 3% | 15% | |||||

| Party / Car ride | ||||||||||||

| Baseline (N = 125) | 22% | 36% | 35% | 7% | ||||||||

| 13% | 19% | 30% | 32% | 50% | 39% | 7% | 10% | |||||

| 30% | 26% | 43% | 38% | 20% | 29% | 7% | 6% | |||||

| Post-Intervention (N = 122) | 33% | 37% | 18% | 12% | ||||||||

| 17% | 32% | 40% | 29% | 27% | 23% | 17% | 16% | |||||

| 47% | 35% | 30% | 47% | 10% | 15% | 13% | 3% | |||||

| Confrontation | ||||||||||||

| Baseline (N = 125) | 21% | 31% | 3% | 45% | ||||||||

| 7% | 23% | 17% | 35% | 7% | 3% | 70% | 39% | |||||

| 27% | 26% | 37% | 35% | 0% | 3% | 37% | 35% | |||||

| Post-Intervention (N = 122) | 28% | 33% | 2% | 36% | ||||||||

| 13% | 29% | 47% | 19% | 3% | 3% | 37% | 48% | |||||

| 40% | 29% | 43% | 24% | 3% | 0% | 13% | 47% | |||||

| CD/PACT | CD/noPACT | |||||||||||

| ctl/PACT | ctl/noPACT | |||||||||||

Figure 2.

Adolescent Virtual Vignette Outcomes

Participants were asked if their virtual decisions mirrored what would be their real-life decisions if the researcher was not present. Nearly every participant (90%) felt that this was the case; this was largely true for participants both with and without a diagnosis of control disorder, although the conduct disorder group tended to rate the experience as less realistic post-intervention compared with the baseline, while the group without conduct disorder felt their decisions reflected reality at both test times. That was also the case regardless of whether the participant agreed with or refused the ECA; that is, the realism rating did not correlate with the outcome of the vignette.

Results of Virtual Vignette Behavior Analyses

Participant behavior was also analyzed in terms of ratings that were observed and recorded by the experimenter (see Paschall, et al., 2005) and by the simulation. General behaviors of the participants included their engagement with the vignettes, verbalizations, comprehension level, and response time (see Table 3). Social competency skills exhibited by the participants included their levels of emotional control, information seeking, provision of information about their own preferences, engaging in negotiation, and being non-provocative (also see Table 3). Length of the conversation between the participant and ECA was also considered.

For most general behaviors, there were no differences between participants who experienced the intervention and those who did not, or participants who were diagnosed with conduct disorder and those who were not, although the behavioral performance measures in general reflected the participants' acceptance of the vignettes. For instance, the participants demonstrated a moderate level of comprehension while using the vignettes, they verbalized while using the application, and they conducted conversations with an average of four conversational turns. (This last finding is important, because the language grammars are shallow and narrow: the ECA has only about 8 to 10 different topic responses per vignette, plus a few generic responses.) In contrast with general behaviors, behaviors that reflect social competency showed differences between groups (F(1,118) = 10.53, p < 0.002), with the participants without conduct disorder exhibiting greater social competency skills than the participants with conduct disorder.

Participants' rated and actual behavior changed between baseline and post-intervention. This was true for general behaviors (F(1,118) = 10.78, p < 0.001) and social skills (F(1,118) = 22.11, p < 0.0001), and suggestive for the length of the conversation (F(1,118) = 3.20, p < 0.08). In all cases, the change was for the better, with behavior demonstrating more engagement or competency. Furthermore, as might be expected, social competency skills (but not general behaviors) improved between baseline and post-intervention more so for those participants who went through the intervention than for those participants who did not (F(1,118) = 7.71, p < 0.01). This finding suggests both that the intervention did indeed focus on the social competencies of interest and that the vignettes were sufficiently engaging to elicit competent social responses.

There were also suggestive differences identified with respect to the use of de-escalation techniques (see Figure 3), such as backing off or apologizing, as noted by the observer. There was a trend for the participants without conduct disorder to issue more de-escalation utterances at post-intervention testing than at baseline, as compared with conduct disorder participants. There was also a trend for the participants who had received the PACT intervention to issue more de-escalation utterances at post-intervention testing than at baseline, as compared with participants who had not received the PACT intervention.

Figure 3.

Adolescent Virtual Vignette Use of De-escalation

Results of Usability/Acceptability Analyses

During debriefing after baseline testing, the participants were asked a series of questions on how they liked the virtual vignette exercises. Participants were asked if the experience was fun, were the vignettes boring or interesting, were they realistic, were they helpful, did they hold the participant's attention, were they silly or stupid, and (for participants who received the PACT intervention) did they relate to the intervention.

There were very few differences among groups. Of some interest, the vignettes kept the attention of the group without conduct disorder more than the conduct disorder group (97% to 83% self-ratings, F(1,118)=5.29, p < 0.02), and the experimental group found the vignettes more helpful than the control group (77% to 51%, F(1,118) = 9.10, p < 0.003). Overall, though, the ratings were reasonably high. More than three-quarters (77%) of participants found the vignettes fun, 82% found them interesting, 45% found them silly or stupid, 70% found them realistic, and 70% found them relevant to the PACT intervention.

Appraisal of free-form participant comments and experimenter notes expand on these findings. A number of participants commented on how they felt the simulation could be improved. About a dozen participants noted the clothing on the ECA, its voice, and/or its vocabulary did not represent what would be seen in their school. Recommendations by participants for changes to the vignettes included different events or confrontations that might occur, ideas about how common or uncommon the presented situations were, and suggested responses that they felt they would make or the ECA should make. Several participants were at first ambivalent to the ECA but then started to provoke the ECA or were persuaded to go along with what was offered. Some participants explicitly stated how they felt, wanting to grab the proffered cash or hit the ECA, in spite of not necessarily enjoying the experience. A number of participants commented on the relevance of the vignettes to past experience or to the PACT situations, noting how the vignettes were a realistic means of assessing how adolescents might actually react.

Discussion

This study examined the validity and reliability of performance measures for a novel set of interactive virtual vignettes that featured an ECA in a school setting. The study found adequate factorial validity with constructs that matched a priori expectations of adolescents' emotional control and interpersonal communication skills. Correlational analyses with the established psychosocial measures provided support for the construct validity of the emotional control measure and limited support for the construct validity of the interpersonal communication skills measure. A similar pattern of results was observed for the criterion-related validity of the performance measures.

Findings also suggest that the PACT violence prevention program may improve negotiation and conflict-resolution skills of this sample of adolescents, who are at elevated risk for becoming perpetrators and victims of violence, especially for those not diagnosed with conduct disorder. Exposure to the PACT Workin' It Out videotape and a brief follow-up discussion with a trained facilitator was significantly and positively associated with a measure for negotiation skills, and was inversely though not significantly associated with an aggressive conflict-resolution style (see Fishbein, Hyde, et al. 2006, for details). The stronger association between the videotape and negotiation skills may be due to the videotape's explicit focus on negotiation skills with interactive role plays involving other adolescents, which were simulated in the virtual vignettes with the ECA. In contrast, the conflict-resolution skills measure was based on hypothetical confrontational situations in a written questionnaire, which was perhaps not as directly related to the videotape as were the virtual vignettes. Thus, the virtual vignettes may be a more sensitive measure of the proximal outcomes targeted by the Workin' It Out videotape.

Study 2. Prisoners

A subgroup of offenders is largely responsible for a disproportionate number of aggressive crimes against persons, high recidivism rates, a significant number of institutional rules violations, high rates of substance abuse, and poor treatment outcomes (Hill, et al., 1996; Rice, 1997; Shine & Hobson, 2000). Studies have consistently found that deficits in ECF correlate with aggression and other forms of persistent misconduct that characterize this subgroup. Prevalence of neuropsychological dysfunction in general is significantly higher in this subgroup than in non-aggressive offenders (Raine, 1993; Reiss, et al., 1994; Rogers & Robbins, 2001; Volavka, 1995). Mounting evidence suggests that integrity of ECF and its modulation of emotion may underlie variability in treatment responses and subsequent post-treatment outcomes (e.g., Aharonovich, et al., 2003). Clinical studies of head injuries, learning disabilities, and cognitive disorders demonstrate that ECF and related behavioral disorders are amenable to appropriately designed treatment (Hermann & Parente, 1996; Manchester, et al., 1997; Rothwell, et al., 1999; Wilson, 1997).

This study assessed the role of ECF and emotional deficits in aggressive prisoners, the usefulness of neuropsychological and emotional measures in characterizing this subgroup, and the ability of these measures to predict treatment response and institutional misconduct. Participants with low ECF and/or emotional perception were expected to be poor responders to treatment, somewhat similar to the participants with conduct disorder in Study 1. As one measure of change, a second series of ECA vignettes pertaining directly to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) components was developed by adapting the Study 1 vignettes for adult offenders.

Methods

Participants

A total of 226 male prisoners were recruited during intake into the CBT program in three Maryland correctional institutions. The institutions were selected for programmatic similarities to ensure continuity of treatment, duration, type and modality of program, and uniformity of treatment provider staff, and other environmental factors. Participants were between 21 and 49 years of age. Prisoners with less than 18 months left on their sentence were excluded, to avoid the stress of pre-release preparations and potential for transfers. Older prisoners, those with chronic drug abuse, mental retardation, dementia, amnesia, or delirium, and those who were illiterate were excluded because these conditions would interfere with performance and/or the prisoner's ability to understand the implications of consent. Although attention deficit disorder is prevalent in this population and may interfere with task performance, prisoners with attention deficit disorder were not excluded, but if they had difficulty completing tasks, they were given breaks and verbal encouragement. In addition, the correctional facilities' management information systems were surveyed to determine prisoners' history of violent crimes and institutional infractions.

Design

Consenting prisoners received baseline testing of several complementary dimensions of ECF and conditions that influence it: two ECF tasks, one emotional perception task, one salivary cortisol responses to an emotionally stimulating task, a test of general neuropsychological functioning, three psychological surveys, and a brief historical inventory to assess prior drug use and childhood and family background. (Further details on the test battery can be found in Fishbein, Scott, et al., 2006.) In addition, interactive ECA vignettes were used to assess actual baseline and post-treatment change in risky decision making. The test sessions each lasted approximately two hours.

CBT Program

After baseline assessments, prisoners completed the CBT program. CBT is the most widespread and rapidly growing treatment program in U.S. correctional institutions to reduce violence, drug abuse, sexual offending, and other behavioral disorders common in prisoners (Holbrook, 1997; Nicholaichuk, et al., 2001). Although there is evidence for the efficacy of CBT, a significant subgroup does not respond, as indicated by high recidivism and relapse rates. CBT was used in this research to identify underlying differences between responders and non-responders to this popular correctional program. CBT is designed to help prisoners develop impulse control, manage anger, and learn new behavioral responses to real-life situations. The underlying assumption is that learning processes play an important role in the development and continuation of antisocial behavior and can be used to help individuals enhance their ability to exert self control. CBT is designed to help patients recognize situations in which they are likely to become agitated or aggressive, avoid these situations when appropriate, and cope more effectively with a range of problems and behaviors associated with aggression. The Maryland correctional system offers a series of three groups that meet for 90 minutes twice a week, totaling 50 sessions. The first group is called entry point and involves curricula on thinking, deciding, and changing. Entry point blends a cognitive restructuring modality (a self-reflective process to search for triggers of misconduct) into a cognitive-behavioral modality (an external, skill-building process). The communication and relationships groups are based on cognitive-behavioral principles. Each facility runs eight to nine cohorts of 14 prisoners each during two 7-month sequences of 50 sessions each.

Decision-making vignettes

Immediately after prisoners completed the CBT program, and again three and six months later, performance was evaluated by staff and by the prisoner. Institutional records were reviewed to assess level of responsiveness to the program, as measured by performance indicators, program completion, and the commission of institutional infractions. Change in risky decision making was assessed both by administering the Cambridge Decision Making Task (which provides participants with options having different probabilities of reward and punishment; Rogers, et al., 1999) and by presenting interactive ECA vignettes during baseline and three months following treatment, as administrators have noted that it takes participants some time to process and apply CBT principles learned.

The ECA vignettes consisted of short, focused interactions to examine dialog, behaviors, and decisions made in a real-world context. Each vignette invoked a specific cognitive function consistent with relevant ECF dimensions measured in the test battery: risky decision making, impulsivity, and sensitivity to penalties. The vignettes required processing of information, judgment, and selection of appropriate and effective decisions. One vignette (involving acceptance of stolen goods) allowed for choices that involve risks where a harmful consequence is possible. A second vignette (involving an invitation to smoke marijuana) measured whether or not prisoners chose a decision before adequate information had been provided, to reflect impulsive decision making. A third vignette (involving a provocation to fight) allowed for choices after a penalty had been dispensed to determine whether or not prisoners had learned to shift strategies. As in Study 1, the vignettes assessed the prisoners' situation-specific behavior rather than merely testing their understanding of risk, impulsiveness, and sensitivity to penalties. Analysis of decisions made in each vignette took into consideration actual behavior of the prisoner, comments made by the prisoner, how the prisoner responded to the ECA, whether the prisoner tailored responses to the situation, and outcome of the situation.

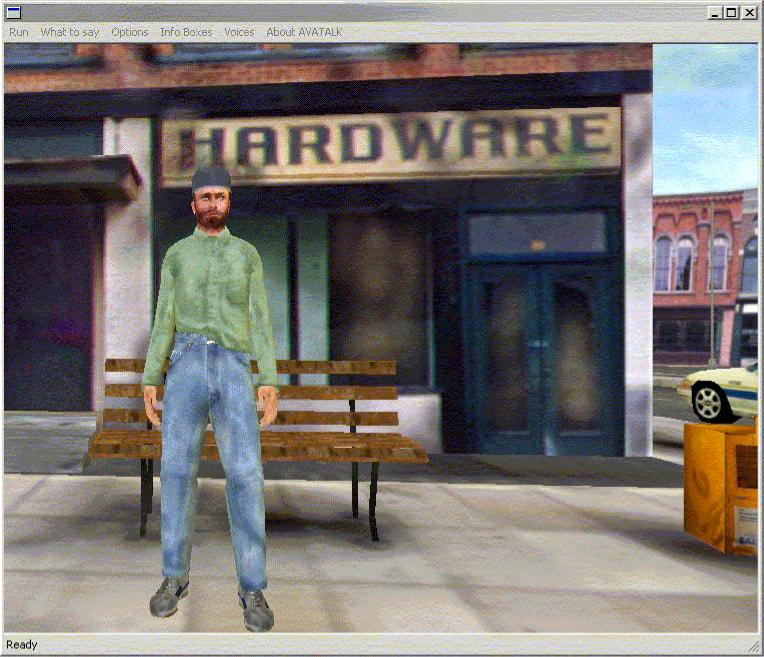

An ECA, a rather mean-looking virtual character (see Figure 4) named Mike, was used to simulate the provocative interpersonal social situations in a street setting. The language the ECA used was modeled on that used by prisoners in the study sample, although, as for Study 1, computer-generated speech was used. Using the same Wizard-of-Oz technique, the prisoners spoke naturally to the ECA while a hidden observer immediately categorized the input. The response of the ECA was controlled by behavior models underlying the ECA simulation, not by the observer. The same algorithm used in Study 1 for ending the conversation was used, in which the ECA would initially entice the risky behavior but gradually back off if the participant demonstrated appropriate avoidance and/or de-escalation behavior (i.e., information seeking, negotiation). The ECA remained in one position on the street, in front of a bench.

Figure 4.

ECA Used in Prisoner Application

Results

Results of Virtual Vignette Outcome

A total of 194 prisoners participated in the baseline ECA interaction; however, due to attrition for a number of reasons, only 97 prisoners participated in both baseline and post-treatment.

Data from the vignettes were analyzed as outcome measures. In contrast to Study 1, there were no differences between baseline and post-treatment outcomes; there seemed to be no “learning,” although, participants did tend to increase the speed of refusal in all vignettes, as reflected in the increase in percent of immediate refusals from baseline to post-treatment in Table 5.

Table 5.

Analysis of Prisoner Responses to Vignettes

| Vignette | Immediate or Near-immediate Refusal | Eventual Refusal | Immediate or Near-immediate Acceptance or Escalation | Eventual Acceptance or Escalation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen goods | ||||

| Baseline (N = 194) | 66% | 21% | 9% | 4% |

| Post-Treatment (N = 97) | 72% | 16% | 11% | 1% |

| Smoking / Car ride | ||||

| Baseline (N = 194) | 87% | 7% | 3% | 3% |

| Post-Treatment (N = 97) | 96% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| Confrontation | ||||

| Baseline (N = 194) | 53% | 10% | 27% | 10% |

| Post-Treatment (N = 97) | 65% | 6% | 25% | 4% |

Results of Virtual Vignette Behavior Analyses

Participants' general behavior while interacting with the ECA and their social skills were analyzed using the same methods as in Study 1. For observed general behaviors that were rated by the experimenter, participants exhibited somewhat greater engagement, verbalization, and comprehension during post-treatment testing compared with baseline testing (F(1,96) = 11.08, p < 0.001). However, as reflected in the lack of differences in outcome data, participants' demonstrated social skills did not differ from baseline to post-treatment, and their total number of responses (i.e., the number of conversational turns) dropped from 2.5 to 2.4, both very low numbers bordering on the lowest value possible given the ECA behavior algorithm, likely indicating a lack of interest or engagement.

Of some interest are vignette-specific differences that manifested in the prisoner data for outcomes (F(2,386) = 29.27, p < 0.0001) that did not manifest to the same extent in the adolescent data. For instance, there was a highly significant correlation between baseline and post-treatment outcomes for the stolen goods (r = 0.65, p < 0.0001) and confrontation vignettes (r = 0.33, p < 0.001), but no correlation for the invitation/event vignette (r = −0.04, n.s.). Similarly, for the confrontation vignette, the situation ended with acceptance or escalation (either immediately or eventually) well over a quarter of the time (see Table 6). Thus, the confrontation vignette seemed to be able to engage participants more than the others. In contrast, the invitation/event vignette, enticed participants only about 5% of the time. These observations are revisited below.

Table 6.

General Behavior by Vignette, Baseline/Post-Treatment, and Population

| Vignette | Adolescents (N = 122) | Prisoners (N = 97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen goods | Population: F(1, 217) = 23.53, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 3.2 | 2.9 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1, 217) = 14.80, p < 0.0002 |

| Post-Treatment | 3.4 | 3.0 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1, 217) = 0.18, n.s. * |

| Party / Car ride / Invitation | Population: F(1, 217) = 20.44, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 3.2 | 2.9 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1, 217) = 15.37, p < 0.0001 |

| Post-Treatment | 3.4 | 3.0 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1, 217) = 0.10, n.s. |

| Confrontation | Population: F(1, 217) = 35.04, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 3.3 | 2.9 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1, 217) = 10.81, p < 0.001 |

| Post-Treatment | 3.4 | 3.0 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1, 217) = 0.25, n.s. |

Significance set at p < 0.01.

Discussion

Prisons have no programs to reliably identify and treat these high-risk prisoners for many reasons; principal among them is the dearth of translational research and the lack of a successful demonstration project. This study related four essential results demonstrated in clinical settings to a corrections setting: the role of ECF and emotional deficits in aggression, the feasibility and efficacy of using a noninvasive test battery to identify high-risk prisoners, the utility of these tests to predict institutional misconduct, and the role of ECF and emotional deficits in differential responses to treatment (see Fishbein, Scott, et al., 2006).

The use of ECA vignettes with this population represents a novel -- but not wholly successful -- means of assessing the effectiveness of CBT and, by extension, the integrity of ECF. The methodology holds promise for extending prior knowledge of the relationship between aggression and ECF to other forms of antisocial behavior by characterizing prisoners who engage in institutional misconduct that has high potential to escalate into a violent episode, interfering with the effective operation of a correctional facility. However, more research is needed to determine the conditions and vignettes that will engage prisoners sufficiently to respond realistically, if at all, to ECA behaviors.

Comparison of Study 1 and Study 2 Results

Because the two studies presented here used very similar virtual vignette exercises and the same procedures, comparison of behavior demonstrated by the adolescents and behavior demonstrated by the prisoners is appropriate. Vignette-specific results and caveats are also given.

Virtual Vignette Behavior Analyses

The first set of analyses reports on general behavior, that is, a measure shown previously to represent one of the dimensions underlying participant behavior (Paschall, et al., 2005). The measure is composed of an aggregate of observer ratings of the participant's engagement level, verbalizations, comprehension level, and reaction time. As Table 6 shows, there was a significant difference between populations (F(1,217) = 26.99, p < 0.0001), with adolescents being rated higher in their behavioral responses to the ECA than prisoners. However, across all three vignettes, there was also a significant difference between ratings before and after the intervention (F(1,217) = 15.18, p < 0.0001). Specifically, the observers felt that participants from both populations (although primarily the adolescents, as discussed above) showed more engagement, exhibited greater comprehension, and verbalized more after the intervention than before. These data suggest that, despite not engaging the ECA in any additional dialog (as discussed next), participants from both populations did “buy into” the conversation with the ECA, more so after the intervention than before.

The second set of analyses reports on total number of responses (i.e., conversational turns) during the interaction between the adolescent or prisoner and the ECA. Values are reported separately for the three vignettes. There was no significant difference in the number of conversational turns between baseline and post-intervention/treatment testing, for either of the populations or for any of the vignettes. As Table 7 shows, there was again a significant difference between populations in the number of conversational turns (F(1,217) = 188.95, p < 0.0001), with adolescents taking significantly longer than prisoners. Additional descriptive analyses revealed that the majority of adolescents did not seek information from or attempt to bargain with the ECA during any of the virtual vignette exercises. However, additional qualitative analysis is needed to better understand whether and how utterances classified as information seeking or negotiation may have differed from other types of verbal interaction with the ECA. These data, nevertheless, suggest that some mechanism or environmental influence leads prisoners not to buy into the conversation with the ECA to the same extent as adolescents, but that it is not the content of the vignettes that matters (for this measure).

Table 7.

Number of Conversational Turns by Vignette, Baseline/Post-Treatment, and Population

| Vignette | Adolescents (N = 122) | Prisoners (N = 97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen goods | Population: F(1, 217) = 63.68, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 4.1 | 2.4 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1, 217) = 1.21, n.s. * |

| Post-Treatment | 4.4 | 2.4 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1, 217) = 1.21, n.s. |

| Party / Car ride / Invitation | Population: F(1, 217) = 128.42, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 3.3 | 2.2 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1, 217) = 1.70, n.s. |

| Post-Treatment | 3.6 | 2.1 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1, 217) = 4.62, n.s. |

| Confrontation | Population: F(1, 217) = 86.73, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 4.2 | 3.0 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1, 217) = 0.03, n.s. |

| Post-Treatment | 4.2 | 3.0 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1, 217) = 0.00, n.s. |

Significance set at p < 0.01.

The third set of analyses reports on social/cognitive skills, which is another measure shown to represent one of the dimensions underlying participant behavior and is composed of an aggregate of ratings of the participants' emotional control, information seeking, provision of information regarding their own preferences, negotiation, and non-provocation. Table 8 supports the conclusions from general behavior, such that both populations demonstrated greater social/cognitive skills after the intervention than before it (F(1,217) = 15.96, p < 0.0001). Perhaps not surprisingly, adolescents did a better job of demonstrating social competency than prisoners (F(1,217) = 43.34, p < 0.0001), and there was a significant trend towards greater increase from baseline to post-intervention/treatment for the adolescents than the prisoners (F(1,217) = 8.16, p < 0.005), suggesting that the intervention had a different impact on the two populations.

Table 8.

Social/Cognitive Skill Level by Vignette, Baseline/Post-Treatment, and Population

| Vignette | Adolescents (N = 122) | Prisoners (N = 97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen goods | Population: F(1,217) = 61.99, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 2.9 | 2.4 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1,217) = 18.13, p < 0.001 |

| Post-Treatment | 3.2 | 2.5 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1,217) = 8.62, p < 0.004 |

| Party / Car ride / Invitation | Population: F(1,217) = 45.12, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Baseline | 2.8 | 2.4 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1,217) = 7.07, p < 0.008 |

| Post-Treatment | 3.0 | 2.5 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1,217) = 2.33, n.s. * |

| Confrontation | Population: F(1,217) = 13.79, p < 0.0003 | ||

| Baseline | 2.6 | 2.4 | Baseline/Post-Tx: F(1,217) = 12.44, p < 0.0005 |

| Post-Treatment | 2.9 | 2.5 | Baseline/Post-Tx*Population: F(1,217) = 5.77, n.s. |

Significance set at p < 0.01.

Vignette-specific Results

Vignette-specific differences are prevalent. This is perhaps not surprising, considering that each vignette required somewhat different skills of the participants. The stolen goods vignette, for instance, required negotiation skills that were addressed in the PACT and CBT interventions nearly to the exclusion of conflict-resolution skills, and did not have an obvious bad outcome. That is, unless the participant had some a priori reason to refuse the offer, it would make sense for him to converse with the ECA and possibly negotiate better terms. As Table 4 shows, before the PACT intervention, adolescent participants tended to accept the offer of stowing the gym bag (fully 50% of participants eventually accepted the offer pre-intervention), but after the intervention, through which they learned to express preferences, only 25% accepted, with nearly half (47%) engaging in some conversation before refusing. Delving further into subgroups, the non-conduct disorder participants exhibited exactly the expected behavior: the level of acceptance for those who did not experience the PACT intervention remained steady, while the level of acceptance for those who did experience the PACT intervention decreased. The conduct disorder participants behaved in a somewhat less clear manner; it is not clear from their behavior what those who went through the intervention retained from it, although they tended towards more conversation and less frequent immediate (impulsive) refusal or acceptance. Meanwhile, as Table 5 shows, prisoners both before and after the CBT treatment tended not to accept the offer (only 12 to 13% did) and did not tend to converse with the ECA. It might be conjectured that these participants (at least those who became engaged with the virtual vignette) had good reason for being suspicious of the offer.

The invitation/event vignette appeared to be the weakest of the three. It generated the fewest number of poor-choice outcomes, particularly for the prisoners. For the adolescents, changes from baseline to post-intervention were generally reflected in the immediate or near-immediate responses, but there do not appear to be systematic changes in the behaviors for any of the participant groups. As Table 7 shows, this vignette also generated the shortest interaction among the three vignettes across all participant groups. Of the three vignettes, this is certainly the least personal to the participant: it would require a perhaps unlikely degree of suspension of disbelief on the part of the participant to become excited about a future event (a party, a possibility of smoking marijuana, a joyride) that would obviously be virtual only, with no actual satisfaction available to the participant. The prisoners definitely did not suspend disbelief to any great extent, and although the adolescent participants who were asked overwhelmingly suggested that their responses reflected how they would really respond in these situations, there is no way to separate the risky outcomes into behavior that reflected reality and behavior that simply reflected interest in the scene and a desire to see where the simulation might go next. Although the intent was to develop a situation where the participant could practice skills such as seeking information and expressing preferences, it is possible that the vignette failed to engage the participants and elicit these skills from them. Ongoing research with adolescents is investigating this possibility.

Of the three vignettes, the confrontation vignette required the most use of conflict-resolution skills and seemed to engage most participants. By far, this vignette elicited the greatest number of poor-choice outcomes in prisoners. For adolescents, in contrast, this vignette demonstrated the largest effects of the PACT intervention, for both the conduct disorder group (eventual escalation was cut nearly in half) and the non-conduct disorder group (eventual escalation was cut nearly to one-third). A possible explanation of these findings is that the prisoners were in prison precisely because of misconduct in similar situations, so it is encouraging that at least the trend (even if not significant) was for better performance after CBT treatment. This kind of vignette might be more relevant to prisoners than to adolescents and thus may better reflect their actual behavior.