Abstract

The design and use of chiral dirhodium(II) paddlewheel complexes as catalysts for asymmetric metal carbenoid and metal nitrenoid reactions, and as Lewis acids have become areas of considerable interest during the past two decades. The metal carbenoid chemistry is especially versatile, encompassing transformations such as C–H insertions, cyclopropanations and ylide formation. A number of different classes of dirhodium(II) catalysts have been found to be broadly effective in this chemistry. This review will highlight that many of these catalysts have higher symmetry than the individual chiral ligands themselves. An introduction of theoretical aspects concerning the structure and symmetry of chiral dirhodium(II) complexes will be given followed by an overview of the major classes of catalysts developed to date. Some representative examples of the synthetic potential of these catalysts will also be discussed.

Keywords: Dirhodium(II) complexes, catalyst design, high symmetry chiral catalysts, synthetic applications, carbenoid chemistry

1. Introduction

Dirhodium(II) complexes are exceptional catalysts for a wide range of transformations. Even though most are extremely stable to heat, moisture and ambient atmosphere, they are exceptionally active catalysts for the decomposition of diazo compounds. The resulting rhodium carbenoids undergo a number of highly selective reactions such as cyclopropanation, C–H functionalization and ylide formation.1 More recently, they have been recognized as effective catalysts in metal nitrene chemistry2 and in Lewis acid-catalyzed cycloadditions.3 Dirhodium(II) catalysis has experienced immense growth over the last few decades and since the early 1980’s it has also been appreciated that the dinuclear scaffold can support chiral ligands.1j Consequently these complexes would have the potential to catalyze asymmetric transformations. Both the design of new catalysts and the spectrum of applications have been developed in a number of directions.4 This review will highlight the advances in this field, with particular emphasis on how the chiral catalysts can possess high symmetry even though the ligands themselves are of much lower symmetry.

Symmetry is an important concept that can play a major role in chiral catalyst design. The use of a high symmetry complex as catalyst will reduce the number of possible substrate trajectories in the catalytic steps of the reaction in question, which in turn can give more defined and predictable transition state structures. Consequently the influencing elements for asymmetric induction can be more effectively controlled and manipulated. The traditional way to produce high symmetry catalysts has been to use ligands of high symmetry. One of the most important classes of high symmetry ligands has been bidentate C2-symmetric ligand, and such complexes of copper (II)5 and ruthenium6 have been very effective in metal carbenoid chemistry. Even higher symmetry catalysts for carbenoid chemistry have been prepared from D2- and D4-symmetric porphyrin ligands.7 The practicality of these complexes, however, has been limited because the ligand synthesis and modification present significant challenges.

This review article will discuss theoretical concepts regarding the symmetry of dirhodium(II) complexes, survey the structures of catalysts that have been developed and highlight applications for each class. Emphasis will be placed on how the dirhodium paddlewheel framework is an excellent scaffold for the design of high symmetry chiral catalysts via a modular approach, in which several identical ligands of low symmetry surround the inherently high symmetry core.

2. Theoretical Considerations

2.1 Structural Features

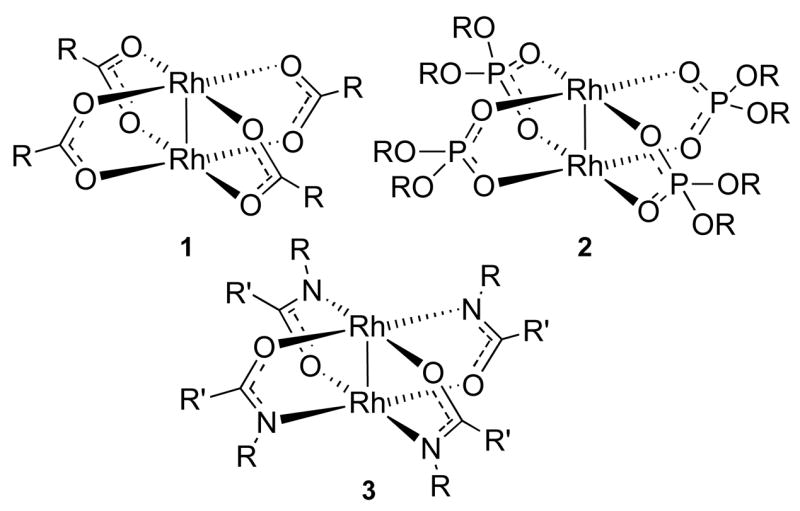

The dirhodium(II) paddlewheel complexes consist of a dinuclear core surrounded by four equatorial μ2-ligands and two axial ligands.8 The core is held together by a rhodium-rhodium single bond and each rhodium is considered to have octahedral geometry.8 Rh2(OAc)4, the parent compound of the dirhodium carboxylates (1) (Figure 1), is D4h symmetrical (1; R = CH3), which is the highest obtainable symmetry for dirhodium paddlewheel complexes. Chiral rhodium carboxylates can possess up to D4-symmetry. Another class of catalysts includes the dirhodium phosphonates (2) in which the dirhodium core is bridged by four phosphonate anions.1j Such complexes can also theoretically achieve D4h-symmetry but those of chiral phosphonates are limited to D4. Complexes of carboxamides (3) have a somewhat more complicated structure since this ligand type bridges the dirhodium core via both an oxygen and a nitrogen atom. The preferred geometry is the cis-(2,2) configuration, which defines that each rhodium is bound to two nitrogen atoms and two oxygen atoms in a cis-fashion.1j These complexes can only obtain C2-symmetry due to this intrinsic ligand binding propensity.

Figure 1.

General structures of dirhodium (II) complexes.

The axial ligands are labile and therefore occupy the catalytically active sites of the paddlewheel complex. The lantern structure is generally considered to remain intact during reactions at these sites although some alternative models have been proposed where the equatorial ligands dissociate. However, these have not yet gained general acceptance.9

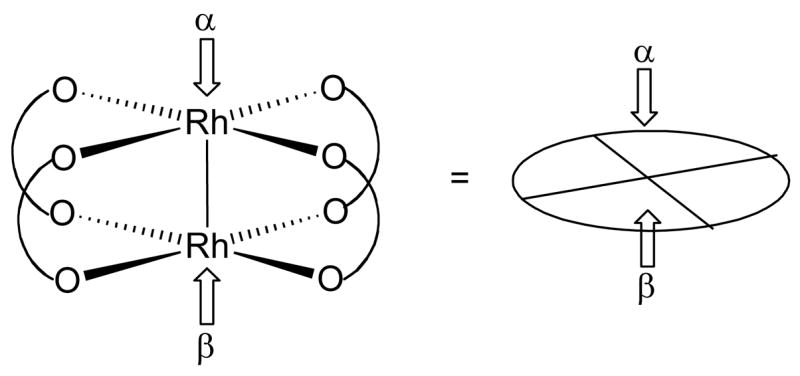

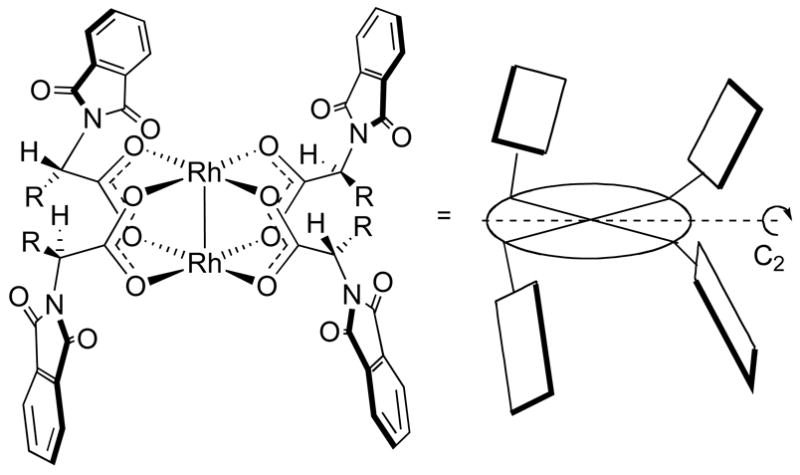

Let us now consider how chiral ligands (R and R’) influence the space around the axial active sites of the catalyst by introducing a simple model.10 A dirhodium complex can be represented by a disk that corresponds with the O – Rh – O plane with the Rh active site in the center (Figure 2). In order for ligands to exert a chiral influence on the course of reactions at the active site, they must necessarily possess geometrical features such that the space above the O – Rh – O plane is sterically restricted to favor only one enantiotopic substrate trajectory.4b This means that sterically blocking groups from the equatorial ligands must point towards the O – Rh – O plane. The two faces of the catalyst have arbitrarily been assigned as α (top face) and β (bottom face) so one can distinguish which face each ligand influences. With these definitions in hand, one can now consider the symmetries inherent in such systems.4b

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of paddlewheel complexes.

2.2 Ligand Arrangements

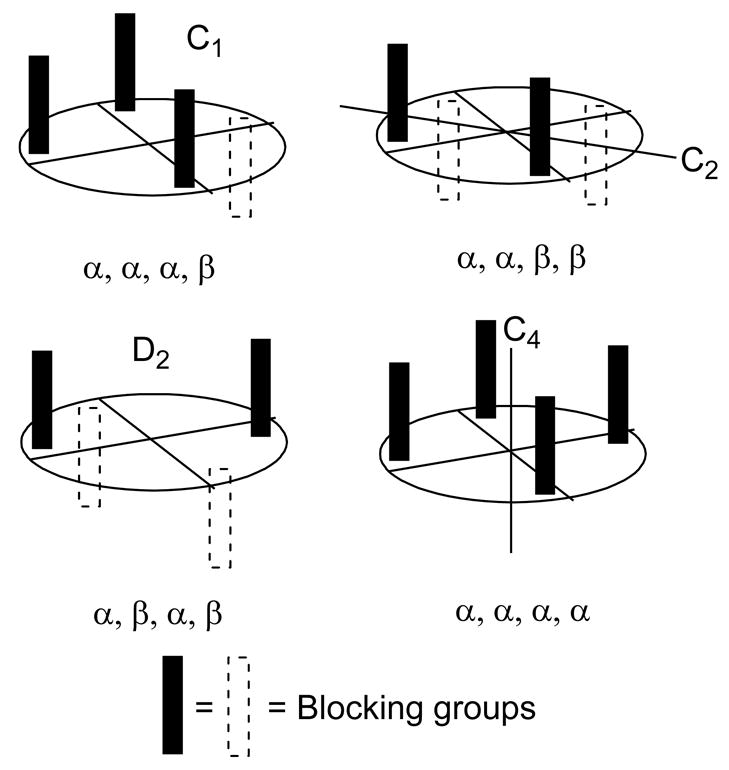

2.2.1 Ligands of C1 Symmetry

The different possible arrangements of chiral C1-ligands are first assessed. The sterically blocking groups creating the chiral pocket around the active sites are pictured as rods, where filled rods represent groups influencing the top (α) face, and unfilled rods the bottom (β) face of the catalyst.10 In catalysts affording high enantiocontrol, the blocking groups cannot lie in the periphery of the catalyst. Because of this, the number of conformational permutations of the system can readily be derived. The groups can either orient themselves on the α-face or on the β-face of the catalyst. Four possibilities then arise: these are α, α, α, α (C4-symmetry), α, α, α, β (C1-symmetry), α, α, β, β (C2-symmetry) and α, β, α, β (D2-symmetry) (Figure 3).4b, 10 From these considerations, it is clear that only the C2-or D2-complexes possess two equivalent catalyst faces.10 Indeed, the major effective catalyst classes based on the dirhodium scaffold belong to these point groups. The C1 complex contains two faces affording different enantiocontrol, and it is likely that the single chiral influencing group on the β-face will give low or no enantioinduction. For the C4-complex, the kinetically more active β-face is essentially achiral, so enantiocontrol will likely be overall low or absent.4b

Figure 3.

Permutations of four C1-ligands.

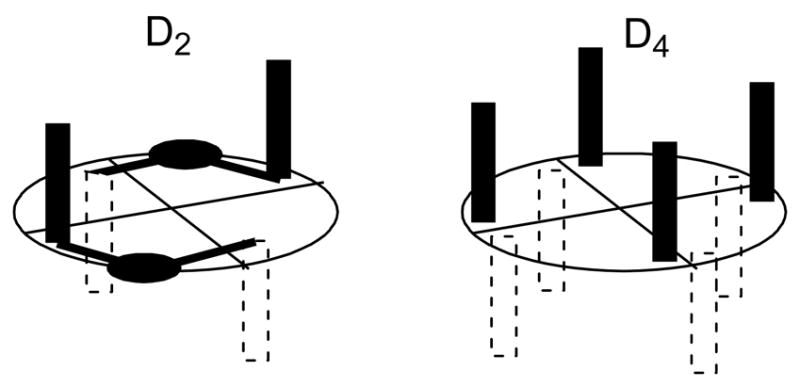

2.2.2 Ligands of C2-Symmetry

If the ligand itself possesses C2-symmetry, even higher overall symmetry is accessible to the complex. A C2-symmetric ligand will influence both faces of the catalyst and give the complex overall D2- or D4-symmetry depending on the geometry of the ligand. Four ligands of C2-symmetry will give overall D4-symmetry to the complex.4b This is in many regards the optimal symmetry of a chiral dirhodium paddlewheel catalyst, since not only are both faces equivalent, but all staggered binding orientations of the axial substituent involved in the asymmetric reaction are also identical with respect to the approaching substrate. D2-symmetry is achieved with two bridged C2-symmetric ligands, thereby affording a more rigidly defined version of the α, β, α, β-form of complexes with C1-ligands (Figure 4).4b

Figure 4.

Arrangements of C2-ligands.

The advantages offered by the dirhodium scaffold in catalyst design are evident from considerations presented in this section. The catalysts can be assembled by a modular approach, in which coordination of several identical low symmetry chiral ligands around the inherently high symmetry core affords an overall high symmetry chiral catalyst.4b However, several factors are involved in determining the orientation of the individual ligands when coordinated to the dirhodium core, and it can be difficult to assess a priori whether a complex consisting of four C1-ligands will preferentially adopt a high symmetry conformation or not. Controlling factors include solvent induced conformational preferences, flexibility of the blocking group and the polarity of the ligand.4b,10

3. Catalyst Structure and Applications

3.1 Rhodium(II) Carboxylates

3.1.1 Proline Derived Complexes

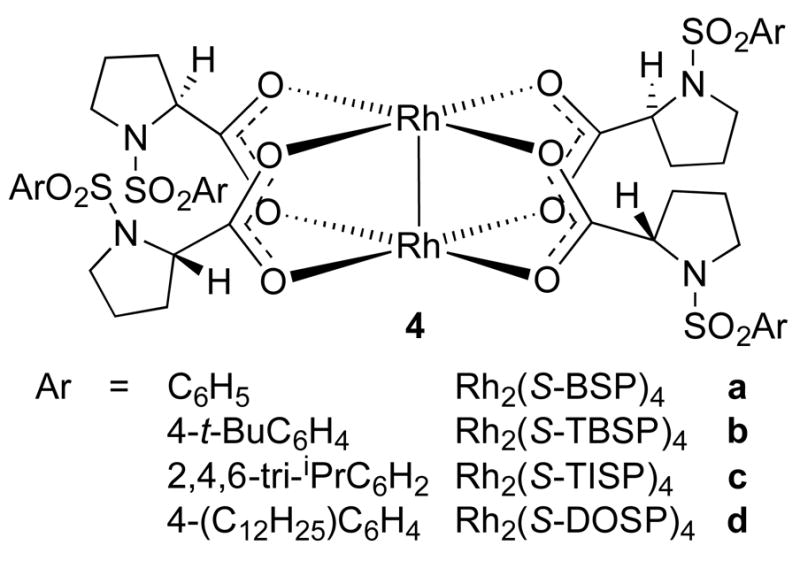

The dirhodium(II) carboxylates are attractive catalysts, particularly for carbenoid transformations, due to their electron deficient character. This class is therefore kinetically very active for decomposition of various carbene precursors.1j Chiral dirhodium(II) complexes based on optically active carboxylic acids were first systematically evaluated by Brunner in a test cyclopropanation between ethyl diazoacetate and styrene.11 The results, however, were very poor (≤ 12% ee) and this led to the preliminary conclusion that dirhodium tetracarboxylates would not be effective catalysts for asymmetric transformations.12 This impression began to change in the early 1990’s as McKervey and Hashimoto demonstrated that chiral dirhodium tetracarboxylates were capable of inducing moderate levels of asymmetric induction in intramolecular C–H insertions.1a-e Dirhodium(II) tetraprolinates were shown to be capable of affording up to 82% ee in intramolecular C–H insertions,13 and their utilization was subsequently greatly expanded by the discovery by Davies that they are exceptional catalysts for reactions of donor/acceptor-substituted carbenoids.10 The original catalyst, Rh2(S-BSP)4 (4a)(Figure 5), developed by McKervey has been optimized by Davies to the more soluble catalysts Rh2(S-TBSP)4 (4b) and Rh2(S-DOSP)4 (4d).

Figure 5.

Representative prolinate based complexes.

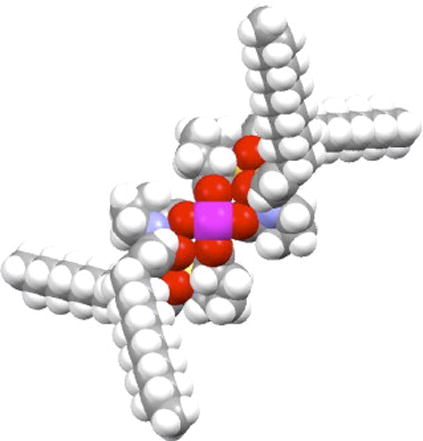

The arylsulfonyl groups in these complexes can only be directed in an up (α) or down (β) fashion pointing out of the O – Rh – O plane on both faces of the catalyst. The conformation in which the arylsulfonyl group lies in the periphery of the catalyst is not favored since considerable steric conflict with the adjacent ligand prevents this orientation.4b The α, β, α, β-arrangement leads to a high-symmetry D2-complex.10 The high levels of asymmetric induction exhibited by these catalysts has been proposed to arise from their preferred D2-symmetric orientation in solution.4b A molecular model of Rh2(S-DOSP)4 (4d) in a D2-symmetric conformation, viewed along the principal symmetry axis, is shown in Figure 6. The N-dodecylarylsulfonyl groups are stretched out and arranged in an α, β, α, β-orientation affording two equivalent Rh active sites with sufficiently sterically encumbering groups to restrict nucleophile trajectories to the axial carbene ligand. Despite the expected free rotation of the prolinate ligands, and thereby the potential existence of many conformations, the D2-symmetric form is the most reasonable for rationalizing the observed enantioselectivities in many reactions.4b,10 The absolute stereochemistry of the products can be accurately predicted from this conformation of the catalyst.1d The model is furthermore consistent with observed solvent effects on enantiocontrol.4b The dirhodium(II) prolinates usually give high enantioselectivities in hydrocarbon solvents and significantly lower values even in slightly polar solvents such as dichloromethane.4b Studies by Jessop and co-workers on Rh2(S-TBSP)4 (4b) confirmed that enantioinduction decreases with increasing dielectric constant for asymmetric cyclopropanation in supercritical fluoroform.14

Figure 6.

Top view molecular model of Rh2(S-DOSP)4

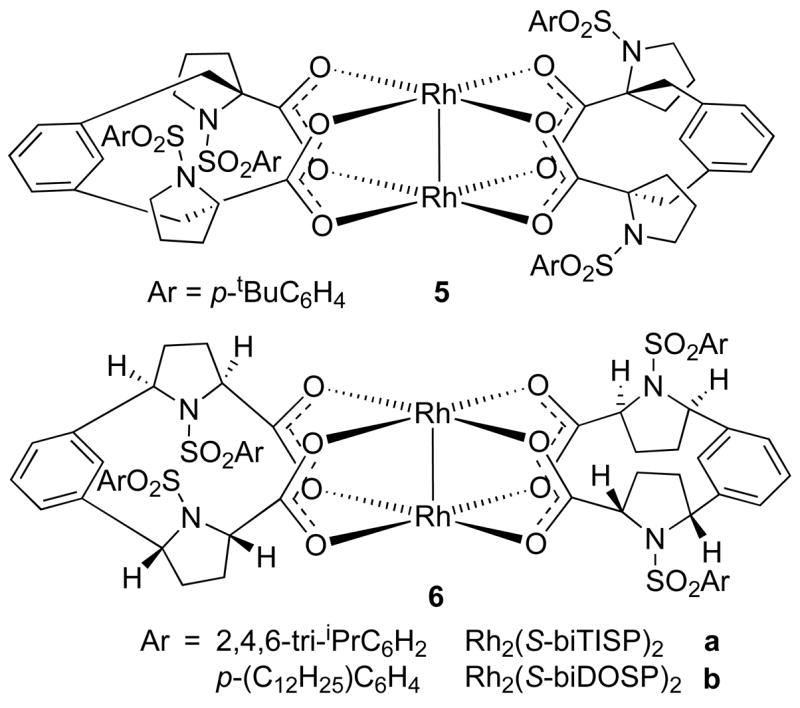

Based on the D2-symmetry hypothesis, Davies designed a second generation of prolinate complexes in which the arylsulfonyl groups are conformationally locked in the α, β, α, β-arrangement.15 This was achieved by synthesizing a C2-symmetric dicarboxylate ligand with two arylsulfonylprolinates linked together. High temperature ligand exchange reactions with Rh2(OAc)4 afforded complexes 5 and 6 (Figure 7). Complex 5 contains a bridging meta-xylene unit attached to C-2 of both proline rings, whereas complexes 6a-b possess meta-benzene bridges at C-5 on both proline rings. Both complexes are locked in a D2-symmetric arrangement due to restricted rotation of the ligands.10, 4b, 15

Figure 7.

Second generation prolinate complexes.

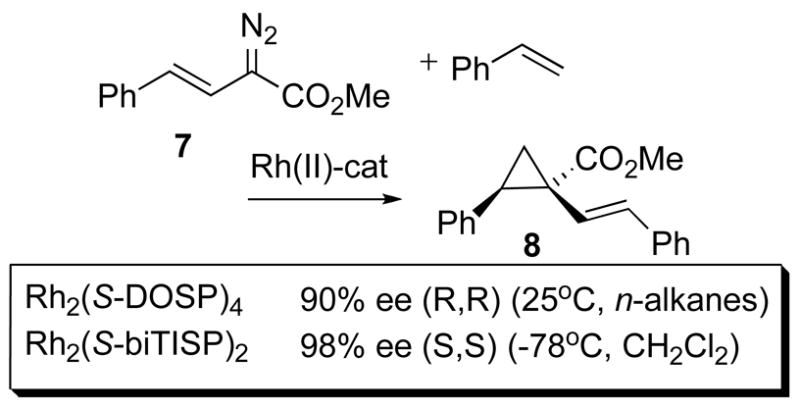

Dirhodium(II) complexes can effectively catalyze cyclopropanation reactions via carbenoid intermediates.1j The choice of catalyst depends on what type of cyclopropanation is desired and the structure of the carbenoid precursor. For intermolecular cyclopropanation with aryl or vinyldiazoacetates the dirhodium(II) prolinates are superior catalysts and high enantiocontrol and chemoselectivity are readily achieved.1j For example, in the reaction of styrene with vinyldiazoacetate 7 (Scheme 1) the cyclopropane 8 can be obtained in 98% ee with Rh2(S-DOSP)4 (4d) and 98% ee with Rh2(S-biTISP)4 (6a).16,17 Highly enantioselective cyclopropanantion reactions with Rh2(S-DOSP)4 have also been developed for aryldiazoacetates, heteroaryldiazoacetates18 and alkynyldiazoacetates.19

Scheme 1.

Cyclopropanation.

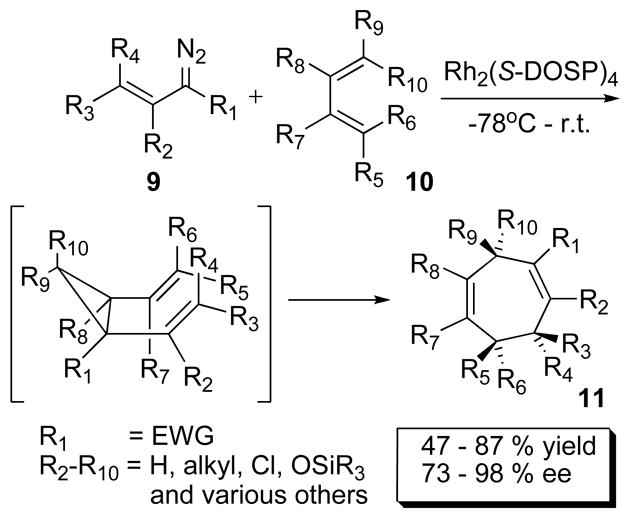

The combination of Rh2(S-DOSP)4 (4d) as catalyst and vinyldiazoacetates (9) in the presence of conjugated dienes 10 affords powerful methodology for the formal, enantioselective [4+3] cycloaddition to form cycloheptadienes 11 via a tandem cyclopropanantion/Cope rearrangement (Scheme 2). The method gives full control of the relative stereochemistry at up to three stereogenic centers.1c A variety of substitution patterns are tolerated and the cycloheptadienes are formed with high asymmetric induction (73–98% ee). An intramolecular version of this methodology has been used in the enantioselective synthesis of epi-tremulane20.

Scheme 2.

Generalized [4+3] Annulation.

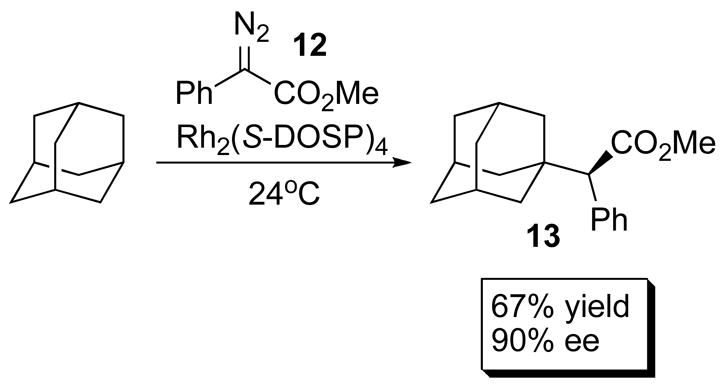

Enantioselective intermolecular C–H functionalization mediated by metal carbenoids has become a powerful technique since the realization that dirhodium(II) complexes readily catalyze such processes.1d With donor/acceptor carbenes (derived from aryl or vinyldiazoacetates), the dirhodium prolinates have been shown to be the best catalysts for these transformations. These carbenes readily insert even into unactivated C–H bonds and are capable of achieving very high regio-, diastereo- and enantioselectivity.1d An example is the reaction of phenyldiazoacetate 12 with adamantane, which generates the C–H insertion product 13 in 90% ee and with full selectivity for the tertiary position (Scheme 3). Similarly, enantioselective C–H insertions in aliphatic systems have been achieved α to heteroatoms, such as in THF and N-Boc pyrrole.21 The reaction has been utilized extensively in the synthesis of several pharmaceuticals and natural products, including Ritalin, Imperanene,22 Indatraline23 Cetiedil and Venlafaxine.24 The methodology has also been expanded to provide surrogates for classical organic reactions such as the Aldol reaction,25,26 the Claisen condensation27 and the Mannich reaction.28

Scheme 3.

Aliphatic C – H Insertion into Adamantane.

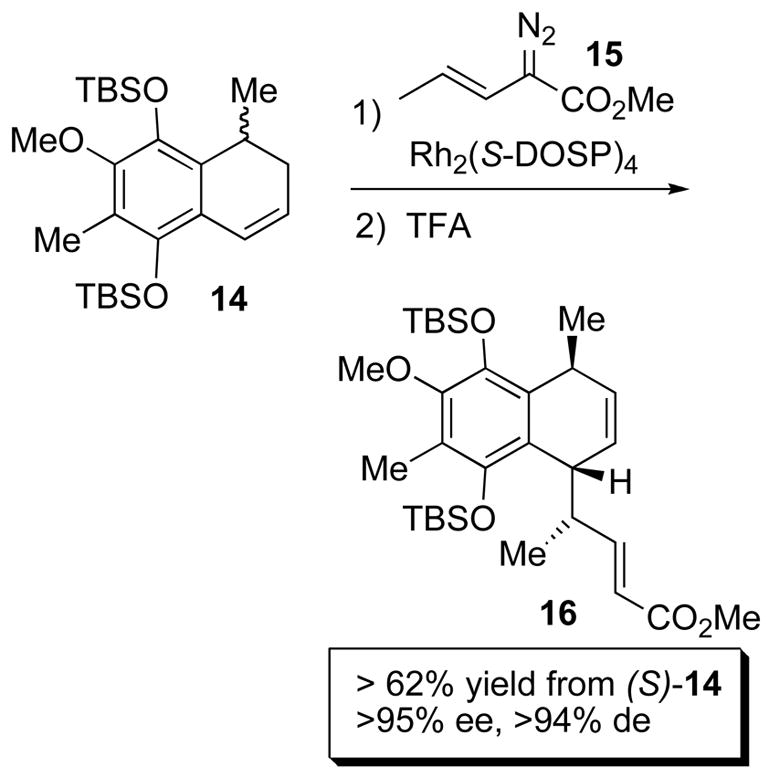

Another efficient transformation catalyzed by Rh2(S-DOSP)4 (4d) is the combined C–H activation/Cope rearrangement.29 This powerful methodology has also been utilized in the synthesis of pharmaceutical targets30 and natural products. One of the most impressive examples is a key step in the total syntheses of Colombiasin A and Elisapterosin B (Scheme 4).31 The Rh2(S-DOSP)4-catalyzed reaction of vinyldiazoacetate 14 with dihydronaphthalene 15 results in an enantiodivergent step in which only one enantiomer of 15 undergoes the combined C–H activation/Cope rearrangement to form 16 in >95% ee and >94% de. This reaction generally proceeds with higher enantioselectivity than the direct C – H insertion.

Scheme 4.

Combined C – H Activation/Cope rearrangement.

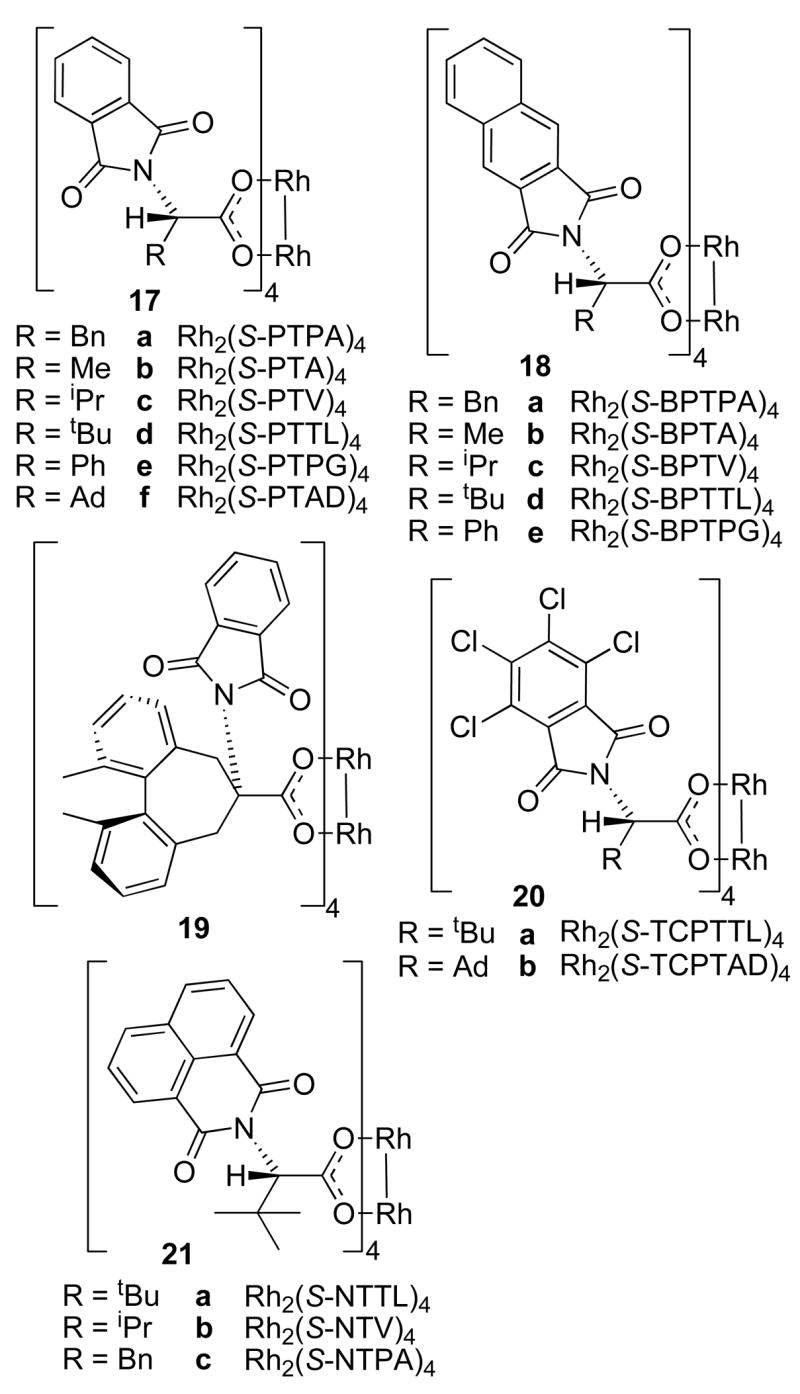

3.1.2 Phthalimide Derived Complexes

Ikegami, Hashimoto and co-workers developed a series of phthalimide protected amino acid derivatives as ligands for dirhodium(II) complexes (Figure 8).1j The optimum catalyst can vary depending on the specific reaction, but usually the tert-leucine derived catalyst Rh2(S-PTPA)4 (17a) gives the highest asymmetric induction.1j The crystal structure of Rh2(S-PTPA)4 (17a) shows the phthalimido groups aligned in an α, α, β, β-fashion around the dirhodium core, giving these complexes overall C2-symmetry.32 It has been assumed that this is the catalytically active conformation also in solution.32 A perspective model of the phthalimide derived complexes is shown in Figure 9 which shows the alignment of the phthalimide groups and the overall symmetry.32

Figure 8.

Representative phthalimide derived dirhodium(II) complexes.

Figure 9.

Perspective model of phthalimide complexes.

The Hashimoto group and others have prepared many derivatives by extending the length of the phthalimide moiety (18a-e), using halogenated phthalimides (20a-b) and by variation of the R-groups (17a-f, 19) (Figure 8).33 Müller used the same scaffold but changed the phthalimido-portion to give complexes 21a-c.34 Davies and co-workers recently synthesized the adamantyl glycine derived complexes Rh2(S-PTAD)4 (17f) and Rh2(S-TCPTAD)4 (20b). In several cases, 17f and 20b induce higher levels of enantioselectivity compared to their tert-leucine analogues 17d and 20a.35 The phthalimide derived dirhodium complexes are generally kinetically very active, comparable to the dirhodium prolinates.1j

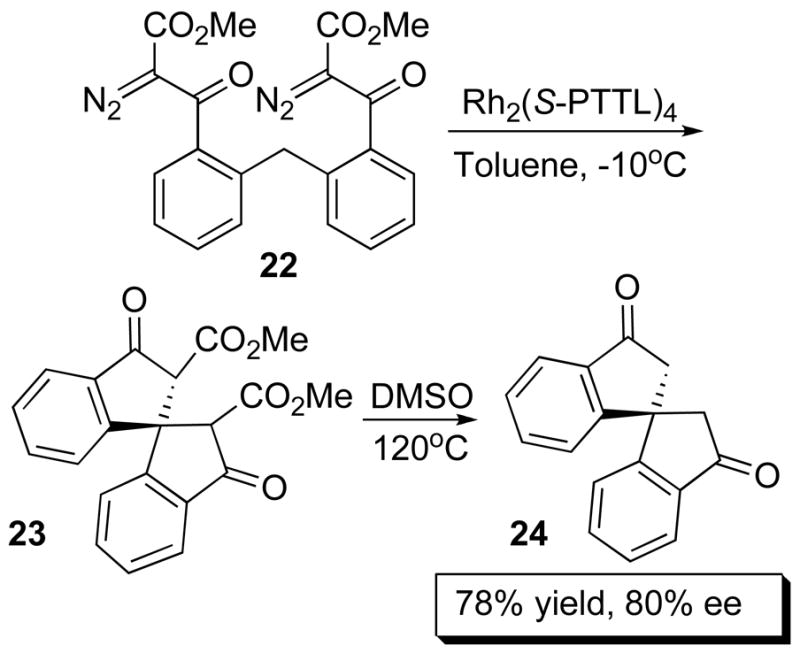

The phthalimide derived dirhodium complexes have been successfully applied in intramolecular C–H insertions with excellent enantiocontrol, particularly in cyclopentanone formation36 but also for β-lactam formation.37 An impressive example is the formation of the spirobicyclic system 24 by double C – H insertion of 22 followed by thermal decarboxylation in 78% yield and 80% ee catalyzed by Rh2(S-PTTL)4 (17d)(Scheme 5). 38

Scheme 5.

Double C – H Activation.

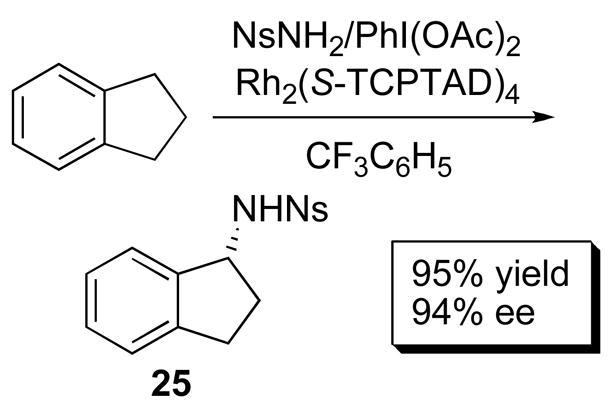

Functionalization of C–H bonds with amines has been a recent area of focus since the transformation can be mediated by dirhodium carboxylate-stabilized nitrenes.39 Impressive diastereocontrol has been reported by Müller, Dodd, Dauban and co-workers in the enantioselective C–H amination of indene (>99% de) in 80% yield with Rh2(S-NTTL)4 (21a). High yield and enantiocontrol was also recently reported by Davies and co-workers in a similar reaction using the newly developed Rh2(S-TCPTAD)4 (20b) (Scheme 6).40

Scheme 6.

C – H Amination.

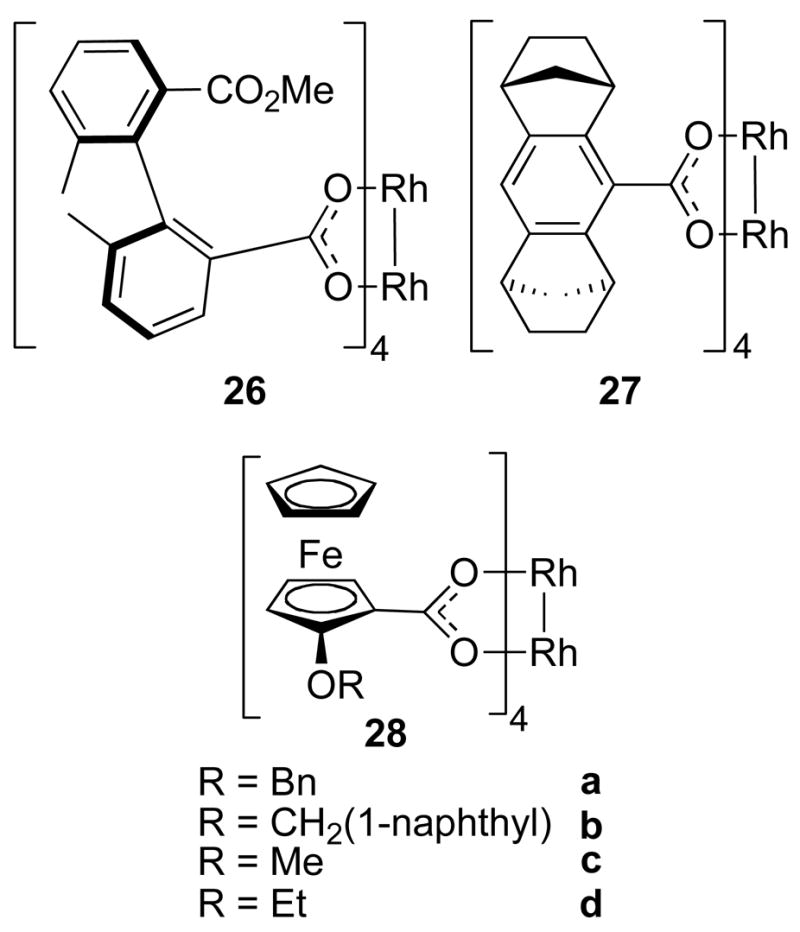

3.1.3 Other Carboxylate Complexes

A range of other chiral dirhodium(II) carboxylate complexes have been prepared, some of which are shown in Figure 10 (26-28a-d).41 None of these have been extensively developed to date, although they do have some interesting design features. Complex 27 is D4-symmetric because each carboxylate ligand has C2-symmetry. Structural information is not available for 28a-d but it is reasonable to speculate that the ligands in these complexes would have a fairly large group unable to align in the periphery of the catalysts. This leads to the possibility that these complexes would adopt a defined high symmetry conformation.4b Hashimoto and co-workers prepared atropisomeric biaryl dirhodium carboxylates of which one example is complex 26. 42 The crystal structure of this complex shows that the ligands adopt the α, α, β, β-alignment giving overall C2-symmetry. The complexes were tested in an intramolecular C – H insertion reaction and afforded moderate enantiocontrol (50–52% ee).42

Figure 10.

Examples of other chiral dirhodium carboxylates.

3.2 Dirhodium (II) Phosphonates

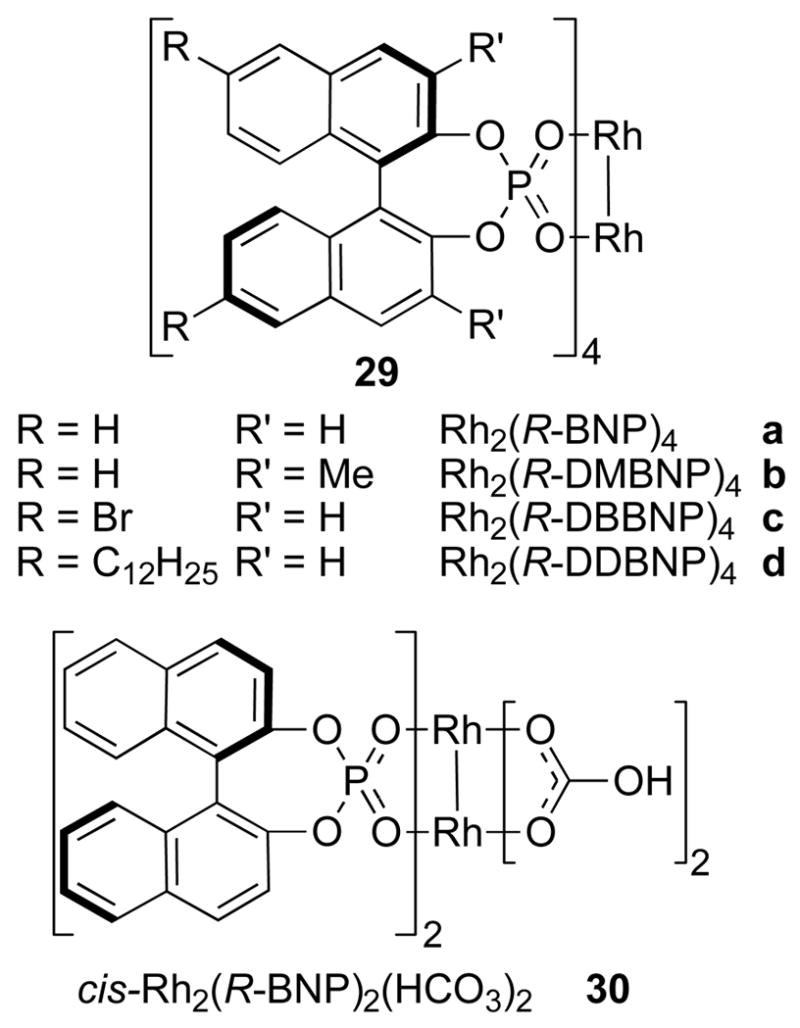

A great example of high symmetry catalysts is the dirhodium(II) binaphthylphosphonates developed independently by McKervey and Pirrung.43 Rh2(R-BNP)4 (29a) has four atropisomeric binaphthylphosphonate ligands around the dirhodium core (Figure 11). Due to the C2-symmetry of the chiral ligands, the overall complex has D4-symmetry. McKervey prepared the mixed ligand system Rh2(R-BNP)2(HCO3)2 (30).44 In this complex, two equivalent C2-symmetric ligands are arranged in a cis-fashion, giving the complex overall C2-symmetry.

Figure 11.

Representative dirhodium(II) binaphthylphoshphonate complexes.

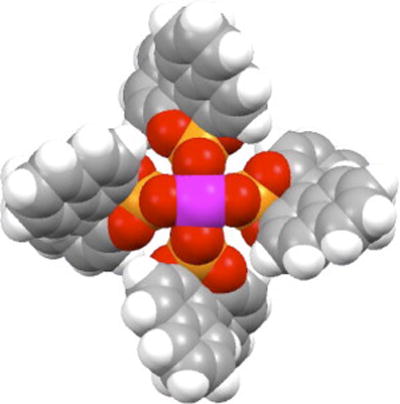

The phosphonate complexes are typically very electron deficient due to the low basicity of the phosphonate ligands.1j This class of catalysts therefore has a somewhat different reactivity profile than the amino acid derived complexes. The tetraphosphonate complexes have shown considerable promise as chiral catalysts which has led to the generation of several new analogues (29a-d).45 The most significant is Rh2(R-DDBNP)4 (29d), which has much improved solubility because of the presence of the n-dodecyl groups. A molecular model of Rh2(S-BNP)4, viewed along the principal axis (Figure 12) shows the propeller-like structure and the D4-symmetry of this family of catalysts.

Figure 12.

Top view molecular model of Rh2(S-BNP)4.

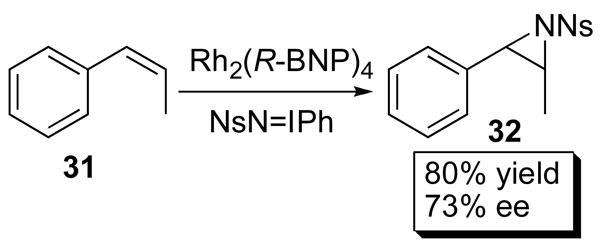

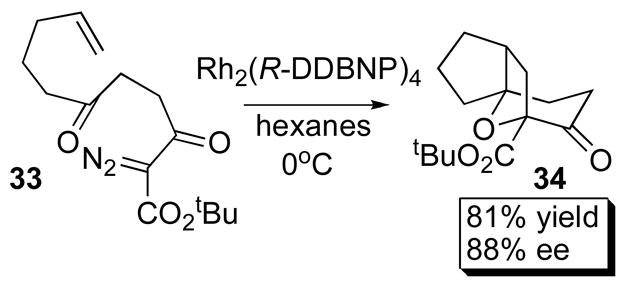

The most impressive applications of the binaphthylphosphonate catalysts have been in ylide reactions of carbenoids and in nitrene insertions.45 Müller utilized Rh2(R-BNP)4 (29a) in the asymmetric aziridination of styrenes and achieved 73% ee with cis-β-methylstyrene 31 (Scheme 7).46 Hodgson successfully employed Rh2(R-DDBNP)4 (34d) in an ylide- mediated intramolecular cycloaddition of 33, which afforded 34 in 81% yield and 88% ee (Scheme 8).45

Scheme 7.

Aziridination.

Scheme 8.

Cycloaddition.

3.3. Dirhodium(II) Carboxamidates

The dirhodium carboxamidates are inherently limited to complexes with overall C2-symmetry.1j This is due to the preferred alignment of the carboxamidate ligands in the cis (2,2) configuration in which two nitrogen and two oxygen atoms are attached to each Rh in a cis-fashion.47 Nevertheless, these catalysts have played a major role in the field, especially in the reactions of the highly reactive carbenoids derived from diazoacetate and diazoacetamide derivatives.1j

Rhodium carboxamidates are very electron rich due to the relatively high basicity of the carboxamide ligands. This also leads to very rigid complexes with negligible ligand exchange occurring at room temperature. The high electron density increases the selectivity of the complexes in carbenoid reactions, but they are catalytically less active than the dirhodium carboxylates.1j

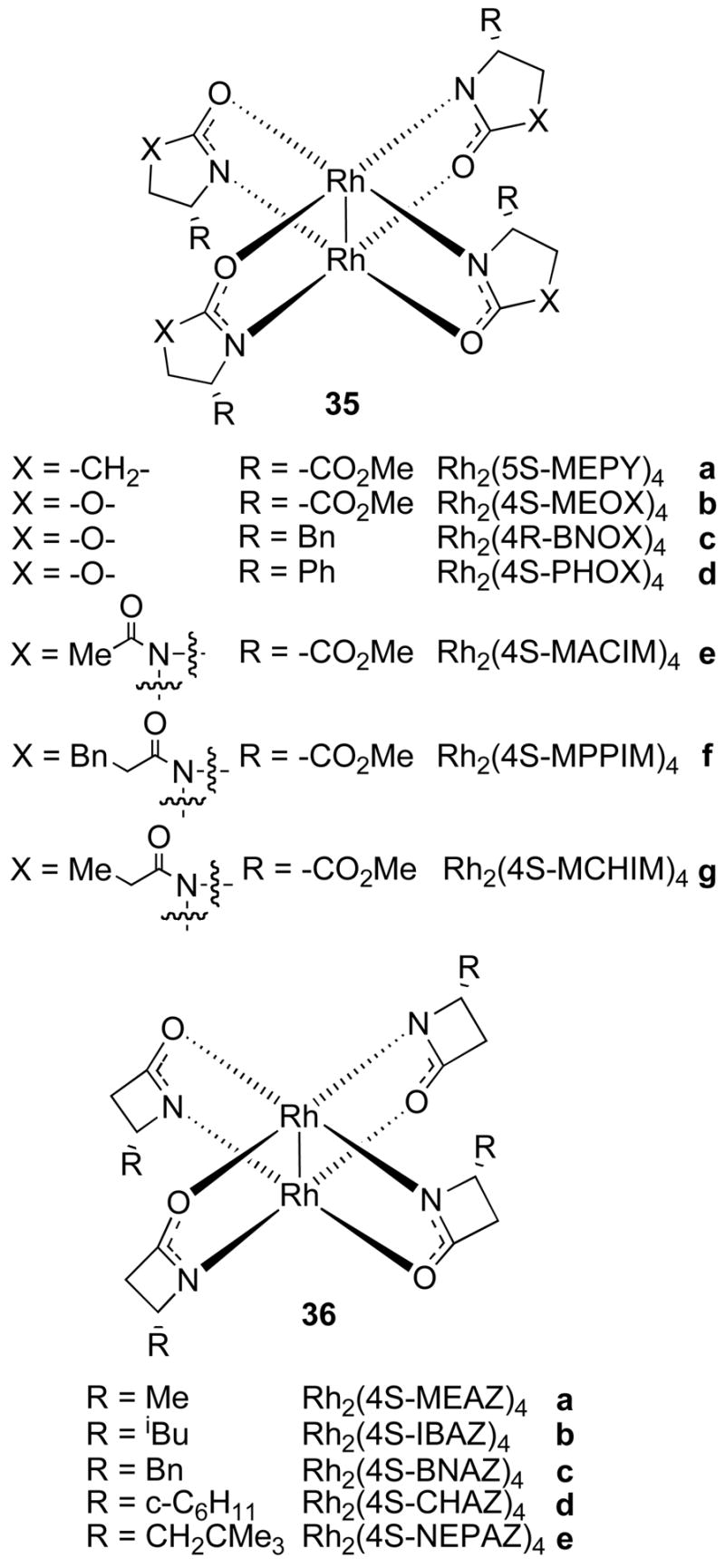

Chiral dirhodium carboxamidates were initially developed by Doyle and coworkers using ligands that were derived from enantiomerically pure α-carboxamides.48 The complexes have since been developed to great diversity with a variety of ligands and ligand substituents (Figure 13). The most important catalysts are derived from 2-oxopyrrolidines49, 2-oxazolidinones50, N-acylimidazolidin-2-ones51 and 2-acetidinones.52 The nature and structure of the carboxamidate ligands have a large influence on reactivity and selectivity of these complexes. For example, the more strained acetidinones lead to elongation of the Rh – Rh bond and hence increase the reactivity of these complexes.53 The perspective models in Figure 13 show the C2-symmetry and the alignment of the ligands in the α, α, β, β-arrangement.

Figure 13.

Representative dirhodium(II) carboxamidate complexes.

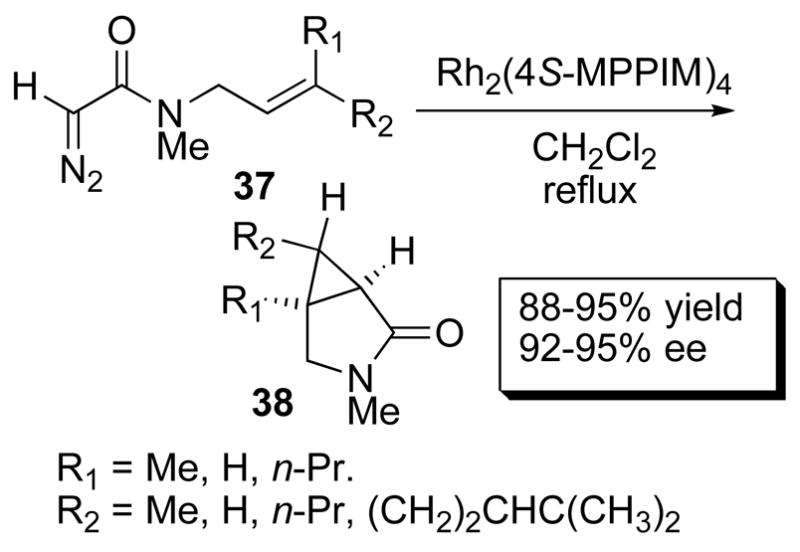

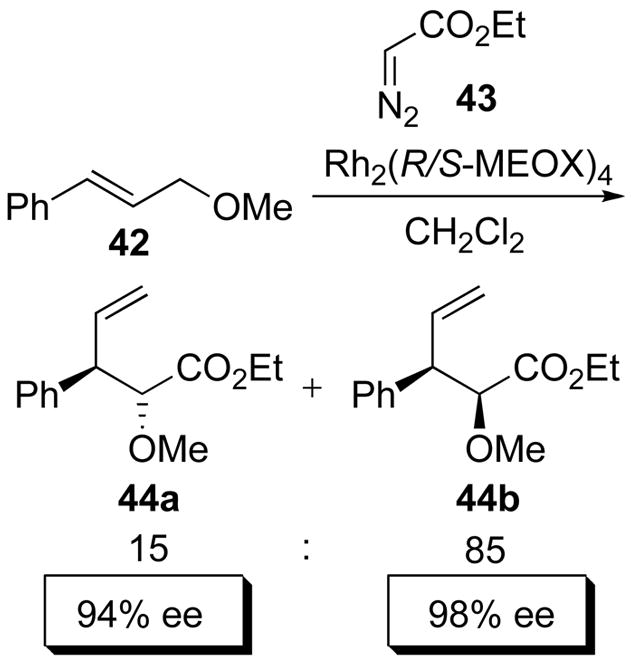

Dirhodium(II) carboxamidates are the catalysts of choice for intramolecular allylic cyclopropanantion.1j,1k Intramolecular cyclopropanation of alkene tethered ester diazoacetates proceeds in high yields with moderate to excellent enantiocontrol with a variety of substituents on the olefin.4a In cases where Rh2(5S-MEPY)4 (35a) does not provide high enantiocontrol Rh2(4S-MPPIM)4 (35f) usually performs better.4a The methodology also extends to the corresponding amides leading to γ-lactam formation in high yields and with excellent enantiocontrol. An example is the intramolecular cyclopropanation of 37 to form lactam 38 with a variety of groups R1 and R2 in up to 95% ee (Scheme 9).1k Intermolecular cyclopropanation with this class of catalysts can be effected in high yields, but with only moderate enantiocontrol.54

Scheme 9.

Intramolecular cyclopropanation.

The dirhodium(II) carboxamidates are particularly suitable catalysts for intramolecular C–H insertions to form lactones or lactams.1d An example is the synthesis of 41 in which intermediate 40 was formed in 86% yield and 96% de from 39 catalyzed by 35e (Scheme 10).1d Chemoselectivity, yields and enantiocontrol are routinely very high (>90% ee) for suitable systems. 55 Enantioselective, intramolecular C–H insertion has been utilized in numerous syntheses, including the syntheses of (+)-Isodeoxypodophyllotoxin,56 Imperanene, (−)-enterolactone and (R)-(−)-baclofen.57

Scheme 10.

Intramolecular C–H insertion.

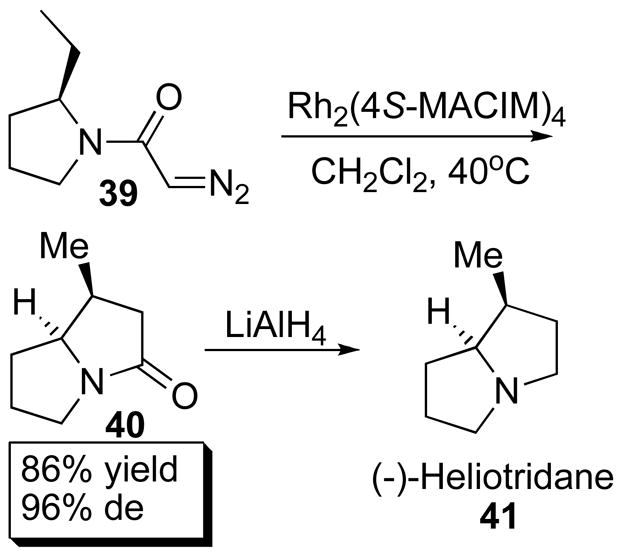

The dirhodium carboxamidates have played an important role in advances made in ylide-mediated chemistry.1j Impressive levels of enantioinduction were achieved in the asymmetric oxonium ylide/[2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 42 with ethyl diazoacetate (43) catalyzed by Rh2(R/S-MEOX)4 (35b) to form the two diastereomers 44a-b, both in >94% ee (Scheme 11).58 Macrocyclization via ylide intermediates is a recently discovered transformation for the dirhodium(II) carboxamidates, but has not been fully developed to date.59

Scheme 11.

Oxonium ylide/[2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement.

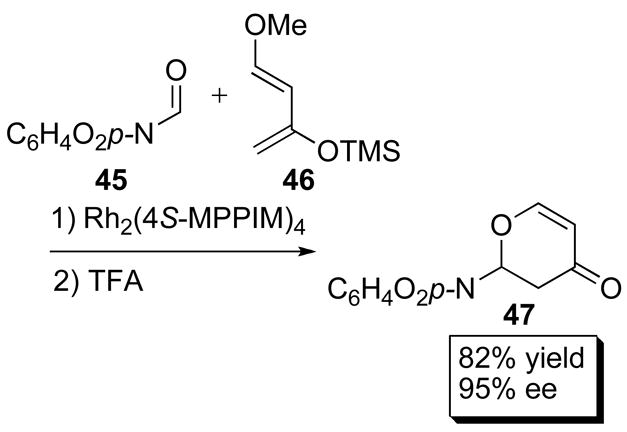

Asymmetric Lewis acid catalysis has been a field of great interest for the last two decades.60 Many chiral Lewis acids have been applied successfully, but one of the major challenges is achieving high enantiocontrol accompanied by high turnover numbers. Traditionally, hetero-Diels Alder reactions usually demand relatively high catalyst loadings because of low turnover numbers.61 Doyle and co-workers reported that the dirhodium (II) carboxamidates effectively catalyzed the hetero-Diels Alder reaction between aldehyde 45 and diene 46 to form 47 (Scheme 12) in 95% ee when catalyzed by Rh2(4S-MPPIM)4 (35f).3 Very low catalyst loadings were required and an impressive turnover number of 10,000 was achieved with reasonable yield and enantioselectivity.

Scheme 12.

Lewis Acid catalyzed hetero Diels-Alder reaction.

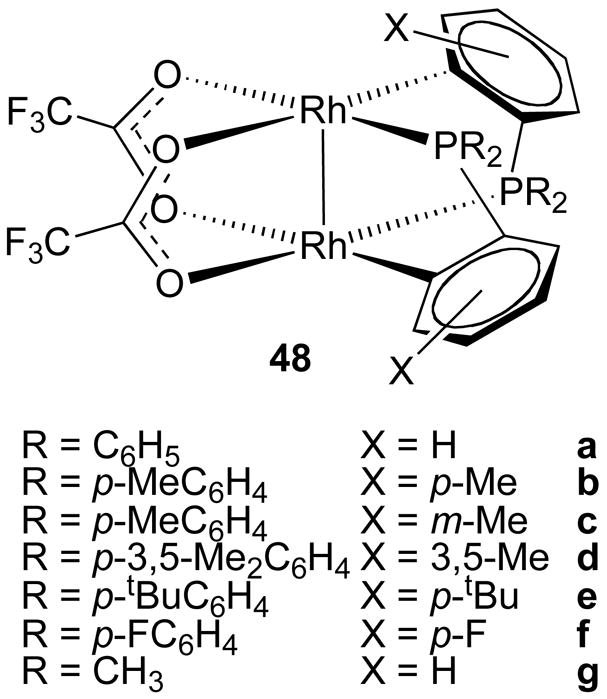

3.4 Orthometallated phosphines

Lahuerta and co-workers introduced a new class of dirhodium catalyst containing two carboxylate ligands and two orthometallated phosphine ligands.62 Several variations of these complexes have been prepared with different substituent patterns 48a-g (Figure 14). The phosphine ligands are in a cis-arrangement oriented opposite to each other giving the overall complex C2-symmetry. This family of dirhodium(II) complexes has not been extensively tested, but up to 95% ee was obtained in intramolecular cyclopropanation of diazoketones.63 Intramolecular C–H insertion to form cyclopentanones afforded up to 74% ee.62

Figure 14.

Dirhodium(II) ortho-metallated phosphine complexes.

4. Conclusions

Although several classes of highly effective chiral dirhodium(II) complexes have been developed as catalysts in asymmetric metal carbene and Lewis acid processes, the importance of high symmetry as a design feature in these complexes has not yet been widely considered. High symmetry chiral complexes can readily be prepared by coordination of several identical lower symmetry ligands onto the dirhodium core. This modular approach for the rapid construction of high symmetry complexes makes this concept particularly attractive. The majority of the ligands that have been used to date have been C1 symmetric, namely prolinates, phthalimide protected amino acids and carboxamidates, leading to catalysts that are considered to exist preferentially in C2 or D2-symmetric conformations. C2-symmetric ligands, such as the binaphthylphosphonates or bridged prolinates, can be used to form rigid complexes of D2 or D4 symmetry. The design elements articulated in this review will hopefully lead to even more superior high symmetric dirhodium catalysts for asymmetric synthesis.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge current and past members of the Davies group who have contributed to our dirhodium catalyst development program. Financial support of this work by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0350536) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.(a) Doyle MP. Chem Rev. 1986;86:919–939. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP. DC Forbes Chem Rev. 1998;98:911. doi: 10.1021/cr940066a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davies HML, Antoulinakis EG. Org React. 2001;57:1–326. [Google Scholar]; (d) Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2861–2903. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ye T, McKervey MA. Chem Rev. 1994;94:1091–1160. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lydon KM, McKervey MA. Ch 16.1 In: Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Vol. 2. Springer; Berlin: [Google Scholar]; (g) Doyle MP. Ch. 5 In: Ojima I, editor. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]; (h) Timmons DJ, Doyle MP. J Organomet Chem. 2001;98:617–618. [Google Scholar]; (i) Sulikowski GA, Cha KL, Sulikowski MM. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1998;9:3145. [Google Scholar]; (j) Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds: From Cyclopropanes to Ylides. Wiley; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]; (k) Lebel H, Francois JF, Molinaro C, Charette AB. Chem Rev. 2003;103:977–1050. doi: 10.1021/cr010007e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Yu XQ, Huang JS, Zhou XG, Che CM. Org Lett. 2000;2:2233. doi: 10.1021/ol000107r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Espino CG, DuBois J. Angew Chem. 2001;113:618. Angew Chem Int Ed, 40; 2001, 598. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zigang L, Chuan H. Eur J Org Chem. 2006;19:4313–4322. [Google Scholar]; (d) Halfen JA. Curr Org Chem. 2005;9:657–669. [Google Scholar]; (e) Espino CG, DuBois J. In: Rhodium(II)-catalyzed oxidative amination, in: Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. pp. 379–416. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Doyle MP, Valuenza M, Huang P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307025101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Valenzuela M, Doyle MP, Hedberg C, Hu W, Holmstrom A. Synlett. 2004:2425. [Google Scholar]; (c) Doyle MP, Phillips IM, Hu W. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5366. doi: 10.1021/ja015692l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Anada M, Washio T, Shimada N, Kitagaki S, Nakajima M, Shiro M, Hashimoto S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2565. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Long J, Hu J, Shen X, Ji B, Ding K. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10. doi: 10.1021/ja0172518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Doyle MP. J Org Chem. 2006;71:9253–9260. doi: 10.1021/jo061411m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:2459–2469. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Lowenthal RE, Abiko A, Masamune S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:6005–6008. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Woerpel KA, Hinman MM, Faul MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:726–728. [Google Scholar]; (c) Müller D, Umbricht G, Weber B, Pfaltz A. Helv Chim Acta. 1994;74:232–340. [Google Scholar]; (d) Lowenthal RE, Masamune S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:7373–7376. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Nishiyama H, Itoh Y, Matsumoto H, Park SB, Itoh K. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2223–2224. [Google Scholar]; (b) Park SB, Nishiyama H, Itoh Y, Itoh K. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1994:1315–1316. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nishiyama H, Itoh Y, Sugawara Y, Matsumoto H, Aoki K, Itoh K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1995;68:1247–1262. [Google Scholar]; (d) Brunner H, Nishiyama H, Itoh K. In: Asymmetric Hydrosilylation and Related Reactions, in: Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. 2. Ojima I, editor. Wiley VCH; New York: 2000. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Callot HJ, Piechocki C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:3489–3492. [Google Scholar]; (b) O’Malley S, Kodaek T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:2445–2448. [Google Scholar]; (c) Maxwell JL, O’Malley S, Brown KC, Kodaek T. Organometallics. 1992;11:645–652. [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen Y, Zhang XP. J Org Chem. 2007 ASAP Article. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Cotton FA, Murillo CA, Walton RA, editors. Multiple Bonds Between Metal Atoms. 3. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Boyar EB, Robinson SD. Coord Chem Rev. 1983;50:109. [Google Scholar]; (c) Felthouse TR. Prog Inorg Chem. 1982;29:73. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ren T. Coord Chem Rev. 1998;175:43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Lou Y, Horikawa M, Kloster RA, Hawryluk NA, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8916–1918. doi: 10.1021/ja047064k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lou Y, Remarchuk TT, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14223. doi: 10.1021/ja052254w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies HML, Bruzinski PR, Lake DH, Kong N, Fall MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6897–6907. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner H, Kluschanzoff H, Wutz K. Bull Soc Chim Belg. 1989;98:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Doyle MP. Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1991;110:305. [Google Scholar]; (b) Singh VK, Arpita D, Sekar G. Synthesis. 1997:137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Kenny M, McKervey MA, Maguire AR, Roos GHP. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1990:361–362. [Google Scholar]; (b) McKervey MA, Ye T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1992:823–824. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roos GHP, McKervey MA. Syn Commun. 1992;22:1751–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wynne DC, Olmstead MM, Jessop PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7638–7647. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies HML, Kong N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:4203. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies HML, Bruzinski PR, Lake DH, Kong N, Fall MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6897. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Davies HML, Hu B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:453. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Kong N, Churchill MR. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6586. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies HML, Townsend RJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:6595–6603. doi: 10.1021/jo015617t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies HML, Boebel TA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8189. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies HML, Doan BD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:3967. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies HML, Hansen T, Churchill MR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3063–3070. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies HML, Jin Q. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:941–949. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies HML, Gregg TM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4951–4953. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies HML, Walji AM, Townsend RJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4981–4983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies HML, Antoulinakis EG. Org Lett. 2000;2:4153–4156. doi: 10.1021/ol006671j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies HML, Beckwith REJ, Antoulinakis EG, Jin Q. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6126–6132. doi: 10.1021/jo034533c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies HML, Yang J, Nikolai J. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:6111–6124. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies HML, Hansen T, Hopper DW, Panaro SA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6509–6510. [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Davies HML, Stafford DG, Hansen T. Org Lett. 1999;1:233–236. doi: 10.1021/ol9905699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. J Org Chem. 2004;69:9241–9247. doi: 10.1021/jo048429m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davies HML, Jin Q. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5472–5475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307556101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manning JR, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1060–1071. doi: 10.1021/ja057768+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies HML, Dai X, Long MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2485–2490. doi: 10.1021/ja056877l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anada M, Kitagaki S, Hashimoto S. Heterocycles. 2000;52:875–883. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Hashimoto S, Watanabe N, Ikegami S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:5173–74. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hashimoto S, Watanabe N, Ikegami S. Synlett. 1994:353–55. [Google Scholar]; (c) Watanabe N, Ohtake Y, Hashimoto S, Shiro M, Ikegami S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:1491–94. [Google Scholar]; (d) Watanabe N, Ogawa T, Ohtake Y, Ikegami S, Hashimoto S. Synlett. 1996:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller P, Bernardinelli G, Allenbach YF, Ferri M, Black HD. J Org Chem. 2004;6:1725–1728. doi: 10.1021/ol049554n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Reddy RP, Lee GH, Davies HML. Org Lett. 2006;8:3437–3440. doi: 10.1021/ol060893l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Denton JR, Sukumaran D, Davies HML. Org Lett. 2007;9:2625–28. doi: 10.1021/ol070714f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsutsui H, Yamaguchi Y, Kitagaki S, Nakamura S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:817–821. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anada M, Watanabe M. Chem Commun. 1998;15:1517–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Z, Chen Z, Jiang Y, Hu W. Synlett. 2003;13:1965–1966. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang C, Robert-Peillard F, Fruit C, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Angew Chem. 2006;118:4757. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang C, Robert-Peillard F, Fruit C, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4641. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy RP, Davies HML. Org Lett. 2006;8:5013–5016. doi: 10.1021/ol061742l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Ishitani H, Achiwa K. Synlett. 1997:781. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pierson N, Fernandez-Garcia C, McKervey MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:4705. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sawamura M, Sasaki H, Nakata T, Ito Y. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1993;66:2725. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hikichi K, Kitagaki S, Anada M, Nakmura S, Nakajima M, Shiro M, Hashimoto S. Heterocycles. 2003;61:391–401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pirrung MC, Zhang J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5987–5990. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCarthy N, McKervey A, Ye T, McCann M, Murphy E, Doyle MP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5983–5986. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hodgson DM, Stupple PA, Pierard FYTM, Labande AH, Johnstone J. Chem Eur J. 2001;7:4465–4476. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011015)7:20<4465::aid-chem4465>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Müller P, Baud C, Jacquier Y, Moran M, Nägeli I. J Phys Org Chem. 1996;9:341–347. [Google Scholar]

- 47.(a) Ahsan MQ, Bernal I, Bear JL. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:260–265. [Google Scholar]; (b) Welch CJ, Tu Q, Wang T, Raab C, Wang P, Jia X, Bu X, Bykowski D, Hohenstaufen B, Doyle MP. Adv Synth Cat. 2006;348:821–25. doi: 10.1021/ac051679y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.(a) Doyle MP. Russ Chem Bull. 1994;43:1770–82. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP. Aldrichim Acta. 1996;29:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Doyle MP, Winchester WR, Hoorn JAA, Lynch V, Simonsen SH, Ghosh R. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:9968–9978. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP, Winchester WR, Simonsen SH, Ghosh R. Inorg Chim Acta. 1994;220:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 50.(a) Doyle MP, Dyatkin AB, Protopopova MN, Yang CI, Miertschin CS, Whinchester WR, Simonsen SH, Lynch V, Ghosh R. Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1995;114:163–170. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP, Whinchester WR, Protopopova MN, Müller P, Bernardinelli G, Ene D, Motallebi S. Helv Chim Acta. 1993;76:2227–2235. [Google Scholar]

- 51.(a) Doyle MP, Austin RE, Bailey AS, Dwyer MP, Dyatkin AB, Kalinin AV, Kwan MMY, Liras S, Oalmann CJ, Pieters RJ, Protopopova MN, Raab CE, Roos GHP, Zhou QL, Martin SF. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5763–5775. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP, Zhou QL, Raab CE, Roos GHP, Simonsen SH, Lynch V. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:6064–6073. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doyle MP, Zhou QL, Simonsen SH, Lynch V. Synlett. 1996:697–698. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doyle MP, Davies SB, Hu W. Org Lett. 2000;2:1145. doi: 10.1021/ol005730q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charette AB, Wurz R. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 2003;196:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davies HML, Dai X. In: Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry III. Crabtree R, Mingos DM, editors. Elsevier; Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doyle MP, Dyatkin AB, Tedrow JS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:3853–3856. [Google Scholar]

- 57.(a) Bode JW, Doyle MP, Protopopova MN, Zhou QL. J Org Chem. 1996;61:9146. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP, Tedrow JS, Dyatkin AB, Spaans CJ, Ene DG. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8907. doi: 10.1021/jo991211t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Doyle MP, Hu W, Valenzuela MV. J Org Chem. 2002;67:2954–2959. doi: 10.1021/jo016220s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Doyle MP, Hu W. Chirality. 2002;14:169–172. doi: 10.1002/chir.10060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doyle MP, Forbes DC, Vasbinder MM, Peterson CS. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7653. [Google Scholar]

- 59.(a) Doyle MP, Hu W. Synlett. 2001:1364. [Google Scholar]; (b) Weathers TM, Jr, Wang Y, Doyle MP. J Org Chem. 2006;71:8183–8189. doi: 10.1021/jo0614902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santelli M, Pons J-M. Lewis Acids and Selectivity in Organic Synthesis. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davies HML. Chemtracts – Organic Chemistry. 2001;14:642–645. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Estevan F, Herbst K, Lahuerta P, Barberis M, Pérez-Prieto J. Organometallics. 2001;20:950. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barberis M, Péres-Prieto J. Organometallics. 2002;21:1667–73. [Google Scholar]