Abstract

The Mo(V) forms of the Tyr343Phe (Y343F) mutant of human sulfite oxidase (SO) have been investigated by continuous wave (CW) and variable frequency pulsed EPR spectroscopies as a function of pH. The CW EPR spectrum recorded at low pH (∼6.9) has g-values similar to those known for the low-pH form of the native vertebrate SO (original lpH form); however, unlike the spectrum of original lpH SO, it does not show any hyperfine splittings from a nearby exchangeable proton. The detailed electron spin echo (ESE) envelope modulation (ESEEM) and pulsed electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) experiments also did not reveal any nearby protons that could belong to an exchangeable ligand at the molybdenum center. These results suggest that under low-pH conditions the active site of Y343F SO is in the “blocked” form, with the Mo(V) center coordinated by sulfate. With increasing pH the EPR signal from the “blocked” form decreases, while a signal similar to that of the original lpH form appears and becomes the dominant signal at pH>9. In addition, both the CW EPR and ESE-detected field sweep spectra reveal a considerable contribution from a signal similar to that usually detected for the high-pH form of native vertebrate SO (original hpH form). The nearby exchangeable protons in both of the component forms observed at high pH were studied by the ESEEM spectroscopy. These results indicate that the Y343F mutation increases the apparent pKa of the transition from the lpH to hpH forms by ∼2 pH units.

Keywords: Molybdenum enzymes, sulfite oxidase, ESEEM, ENDOR, HYSCORE

Introduction

Sulfite oxidase (SO) is a physiologically vital molybdenum enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of sulfite to sulfate, the final step in sulfur metabolism [1]. The X-ray crystal structures of SO from chicken [2], plant [3] and bacterial [4] sources show essentially identical five-coordinate square pyramidal geometry about the Mo center, with three sulfur donors in the equatorial plane. Two of these sulfur donors are from the enedithiolate function of the pyranopterindithiolate (molybdopterin [5]) unit that is present in all molybdenum enzymes, and one sulfur is from a conserved cysteine that is essential for catalytic activity [6]. Two oxo groups, one axial and one equatorial, complete the coordination about the metal in the fully oxidized Mo(VI) state [7,8]. During the catalytic cycle the enzyme passes through the paramagnetic Mo(V) state [9], which shows characteristic EPR spectra that are affected by the exchangeable equatorial ligand (“L” in Fig. 1), pH, anions in the media, and mutation of nearby amino acid residues [10]. These EPR signals were originally classified into three distinct types by Bray in the 1980s from studies of native, wild-type (wt) avian SO, namely, low pH (lpH), high pH (hpH), and phosphate inhibited (Pi) [11-13].

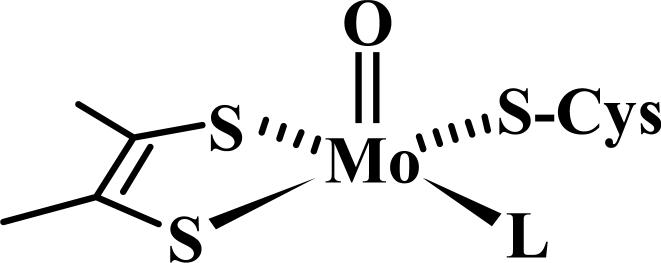

Fig. 1.

Coordination geometry of the Mo(V) center of SO enzymes. Examples are known in which L is OH−, PO43-, AsO43-, SO42-, and possibly H2O [10,33].

The continuous wave (CW) EPR spectrum of the lpH form of wt avian (chicken) SO observed at pH ≤ 7 is characterized by principal g-values of about 2.004, 1.972 and 1.966, and by characteristic splittings at the EPR turning points caused by a strong (∼30 MHz) and predominantly isotropic hyperfine interaction (hfi) with an exchangeable proton of an equatorial OH ligand. The principal g-values of the hpH form of avian SO at pH ≥ 9.5 are significantly different (1.987, 1.964, 1.953), and the isotropic hfi of the exchangeable protons are close to zero [14,15]. Recombinant wt human SO shows lpH and hpH EPR spectra that are virtually identical to the native avian enzyme [16]. These two well-known EPR spectral types will be referred to here as original lpH and original hpH forms of SO.

More recent EPR studies of wt recombinant SO from plant (Arabidopsis thaliana (At-SO)) [17] and bacterial (Starkeya novella (SDH)) [18] sources show that the classification scheme for vertebrate SOs is not sufficient to describe all of the Mo(V) EPR signals observed for these organisms. For At-SO, the nature of the low pH signal depends upon the mode of reduction [17]. One-electron reduction by Ti(III) citrate at pH 6 gives an EPR spectrum similar to that observed for the original lpH form of vertebrates. However, reduction with sulfite at low pH produces a new form of the active center that is characterized by similar g-values, but lacks an exchangeable proton. It was hypothesized that the active site in this form is in the closed conformation that blocks water access to the molybdenum center (therefore, this form was referred to as the blocked form), and as a result, the molybdenum center retains the sulfate ligand. Indeed, the presence of coordinated sulfate was recently confirmed by electron spin echo (ESE) envelope modulation (ESEEM) studies using 33S-labeled sulfite as the substrate [19]. Thus, At-SO exhibits either the blocked low pH form or the original lpH form, depending upon the mode of reduction.

For wt SDH from S. novella, only one EPR form, which closely resembles the original hpH form of vertebrates, is observed at all pH values [20]. Pulsed EPR studies show presence of exchangeable protons in vicinity of the Mo(V) center of bacterial SDH, even though no hyperfine splittings can be detected by CW EPR [18].

These more recent EPR studies of the sulfite oxidizing enzymes from plant and bacterial sources demonstrate that the relationships among the observed EPR spectra, and external conditions (pH, anions), and the structure surrounding the Mo(V) center [10], are more complicated than was originally proposed [13]. In order to understand details of these relationships it is necessary to judiciously and systematically vary the nearby environment of the Mo center of Fig. 1 by site directed mutagenesis. Particularly interesting are nearby amino residues that are conserved across species and which have been implicated in the overall catalytic reaction.

One such important residue is Tyr322 in chicken SO (Tyr343 in human SO) that is located close to the Mo active site and is hydrogen bonded to the sulfate anion that crystallizes in the binding pocket [2]. This tyrosine is conserved in the plant and bacterial enzymes and occupies a similar position relative to the molybdenum in the active site [3,4]. Studies of intramolecular electron transfer (IET) kinetics for chicken SO as a function of pH and concentration of anions led to the proposal that this tyrosine residue plays an important intermediary role in the coupled electron-proton chemistry of SO, especially when an anion blocks direct access of H2O or OH− to the equatorial MoV-OH group [21]. Competing H-bonding interactions of the Mo-OH moiety with Tyr322 (chicken numbering) and with the anion occupying the active site were also proposed to be important in the equilibrium between original lpH and original hpH forms of wt SO [21]. Subsequent laser flash photolysis studies showed that the IET rate constant of Y343F at pH 6.0 is only about one-tenth that of the wt enzyme, suggesting that the OH group of Tyr343 is important for efficient IET in SO [22]. Moreover, the pH dependences of the IET rate constants in the wt and Y343F forms of human SO are consistent with the previously proposed coupled electron-proton transfer mechanism [21].

The importance of this conserved tyrosine has also been demonstrated for bacterial SDH from S. novella, where the analogous mutant (Y236F) is unable to carry out IET and exhibits a CW EPR spectrum that is distinctly different from the wt enzyme and closely resembles the orginal lpH form of wt vertebrate SO [23]. X-ray crystallography shows only minor differences between the wt and Y236F enzymes from S. novella, and it has been suggested that changes in the intervening water structure between the molybdenum and heme domains may be responsible for the large differences observed in the kinetics and the EPR spectra for wt and Y236F proteins of S. novella [23].

In recent years EPR spectroscopy, especially variable frequency pulsed EPR spectroscopy, have proven to be extremely informative and indispensable tools for characterizing the nearby environment of the Mo(V) active centers of SO enzymes (Fig. 1) in order to gain unique insight concerning structure and reaction mechanism [10,24] In this work we use these techniques to address the structural changes at the molybdenum center of human SO enzyme that are induced by the Y343F site mutation, which substitutes the conserved active site tyrosine by the hydrophobic phenylalanine residue.

Experimental

Sample preparation

Recombinant wt and Y343F human SO were expressed and purified as previously described [6,22,25]. Samples for X- and Ku-band EPR measurements were prepared by reducing a solution of the enzyme with excess sulfite in buffers (25 mM bicine, 25 mM pipes, adjusted to desired pH (6.4 − 9.8) with NaOH) as described previously [26]. These buffers were used to minimize pH changes upon freezing in liquid nitrogen [13].

Instruments and measurements

X-band CW EPR measurements were performed on a Bruker ESP 300E spectrometer at a temperature of 77 K. Pulsed EPR measurements were performed at various microwave (mw) bands on a home-built variable frequency pulsed EPR spectrometer using a variety of techniques and operational mw frequencies [27]. Parameters for particular experiments are shown in the Figure captions. The temperature of pulsed EPR measurements was about 21 K.

Results and Discussion

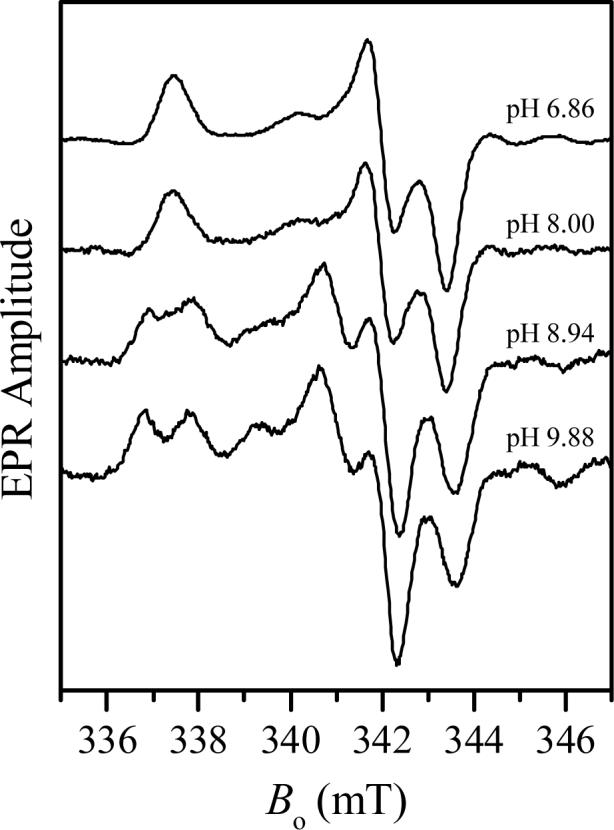

The CW EPR spectra recorded at different pH values are shown in Fig. 2a. At low pH the g-values are characteristic of the original lpH form of the wt enzyme; however, no hyperfine splittings due to a nearby exchangeable proton are seen. Thus, the CW EPR spectrum at low pH strongly resembles the spectrum of the blocked lpH form of At-SO [17]. Increasing the pH (up to pH ≅ 10) leads to a gradual change in the EPR spectrum, and at pH 9.88 the spectrum becomes similar to that of the original lpH form of SO. In particular the hyperfine splittings due to the nearby exchangeable protons are clearly visible at the EPR turning points (these splittings disappear when the sample is prepared in D2O, see Fig. 3). This form will be designated as the original lpH Y343F SO.

Fig. 2.

CW EPR spectra of Y343F SO in H2O as a function of pH (as indicated in the Figure). Experimental conditions: νmw = 9.443 GHz; modulation amplitude, 2.85 G; mw power, 0.2 mW; temperature, 77K.

Fig. 3.

CW EPR spectrum of Y343F SO in D2O at pD 9.4. Experimental conditions: same as in Fig. 2.

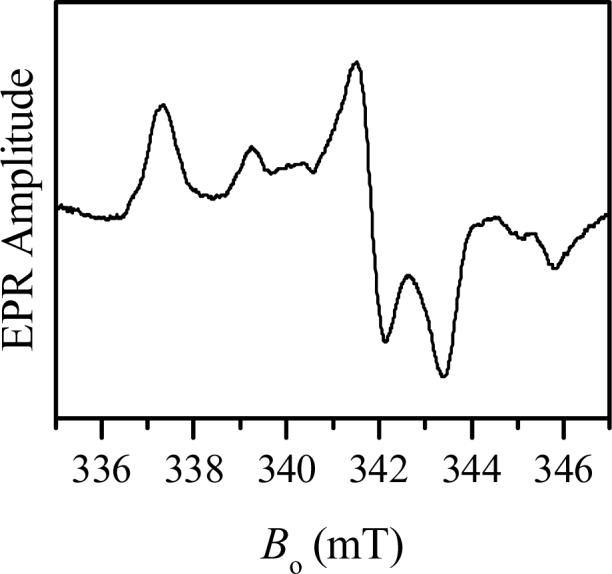

Minor features located at g-values of 1.988 and 1.951 are characteristic for gZ and gX of the original hpH SO (see Table 1). The CW EPR spectrum of Y343F SO at high pH gives the impression that the relative concentration of the original hpH Y343F SO is small. However, the ESE field sweep spectrum (Fig. 4) shows that the contributions of both components, the original lpH and the original hpH, are quite comparable, although the gY turning point of the latter component is broadened by g-strain somewhat more than usual.

Table 1.

Principal g-values of the EPR-active forms of Y343F SO observed in this work in comparison with original lpH, original hpH and blocked forms of SO.

| Mo(V) species [ref] | gz | gy | gx |

|---|---|---|---|

| blocked Y343F SO [this work] (observed at low pH ∼ 6.0) | 1.999 | 1.973 | 1.965 |

| original lpH Y343F SO [this work] (observed at higher pH) | 2.000 | 1.976 | 1.967 |

| original hpH Y343F SO [this work] (observed at higher pH) | 1.988 | 1.961 | 1.951 |

| original lpH vertebrate wt SO [12] | 2.004 | 1.972 | 1.966 |

| original hpH vertebrate wt SO [12] | 1.987 | 1.964 | 1.953 |

| blocked At-SO [17] | 2.005 | 1.974 | 1.963 |

Fig. 4.

Trace 1, two-pulse ESE-detected field sweep spectrum of Y343F SO in D2O at pD 9.4. Experimental conditions: νmw = 17.275 GHz; time interval between the mw pulses, τ = 300 ns; mw pulse durations, 15 ns; temperature, 21 K. Short-dashed trace 2 and long-dashed trace 3 show the approximate decomposition of trace 1 into the original lpH and original hpH spectra.

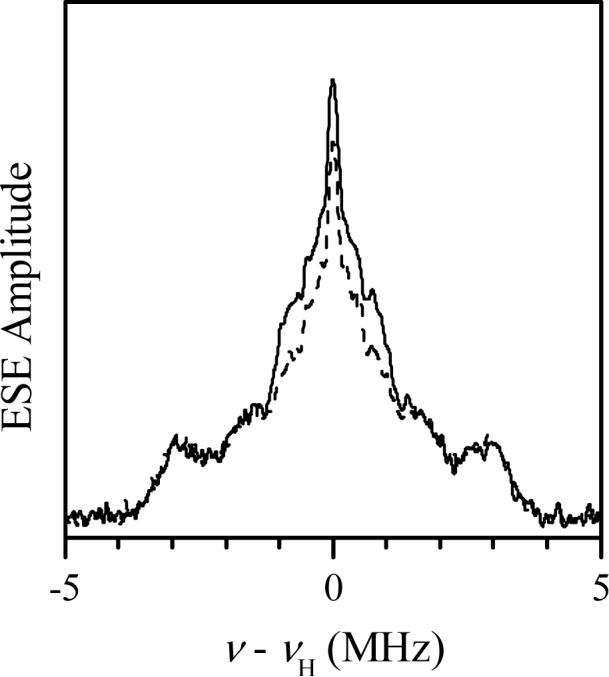

Although the CW EPR spectrum of Y343F SO recorded at low pH does not show any resolved hyperfine splittings (Fig. 2), this cannot be taken as definitive proof that there are no nearby exchangeable protons because our previous study of the original hpH form of SO showed that such protons may be present even though visible splitting of the CW EPR spectrum is absent [14,15]. Therefore, a series of pulsed EPR investigations were conducted on Y343F SO to directly detect nearby exchangeable protons. As an example, Fig. 5 shows 1H Davies ENDOR spectra of the low-pH sample in buffered H2O and D2O solutions recorded at gY, which is the most orientationally non-selective EPR position. These spectra are essentially identical, except for the central part at |ν-νH| < 1 MHz that is enhanced in H2O solution due to presence of numerous distant solvent protons. Thus, there are no indications that the Mo(V) center of Y343F SO at low pH contains a ligand with exchangeable protons. The same conclusion was reached from analysis of the deuterium ESEEM, which was identical to that observed earlier for the blocked form of At-SO [17]. It is therefore very likely that at low pH the hydrophobic phenylalanine of Y343F is blocking water access to the active site, thereby retarding hydrolysis of the MoV-OSO3 entity, similar to the situation found for At-SO at low pH [17].

Fig. 5.

1H Davies ENDOR spectra of Y343F SO at low pH in buffered H2O (pH 6.8, solid trace) and D2O (pD 6.4, dashed trace) recorded at the gY turning point of the EPR spectrum (Fig 3). Experimental conditions: νmw = 9.461 GHz; magnetic field, Bo = 342.5 mT; mw pulse durations, 120, 60 and 120 ns; time interval between the first and second mw pulses, T = 40 μs; time interval between the second and third pulses, τ = 400 ns; RF pulse duration, 20 μs; temperature, 21 K.

At high pH, although the sample is a mixture of various forms, the higher and lower field positions appear to arise solely from the original hpH and original lpH forms (Fig. 2b)[14,15]. These regions can be selectively investigated for the presence of nearby exchangeable protons by pulsed EPR techniques. Since the presence of an exchangeable proton for the original lpH form is evident directly from the EPR spectrum (Figs. 2 and 3), we are mostly interested in the high-field region of the field-sweep spectrum that is contributed by the original hpH Y343F SO only.

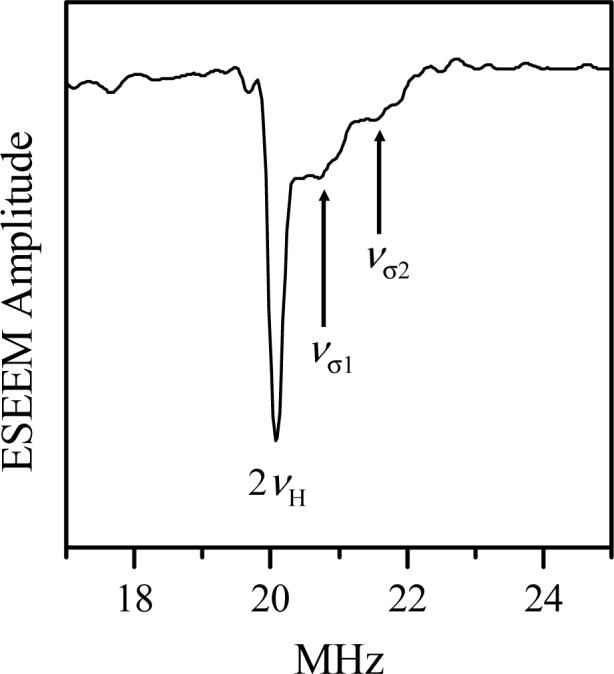

To establish the presence of the nearby exchangeable proton(s) in the original hpH Y343F SO, two different pulsed EPR techniques have been used. The anisotropic hfi for nearby protons was determined from integrated four-pulse ESEEM spectra [28,29] using the shift of the proton sum combination line, νσ, from the double Zeeman frequency, 2νH, according to [30]:

| (1) |

where T⊥ is the anisotropic hfi constant and νH is the 1H Zeeman frequency. To enhance the shift, the experiment was performed at a low operational frequency, νmw = 6.399 GHz. The data were collected at the high-field region of the field-sweep spectrum where the original hpH form dominates.

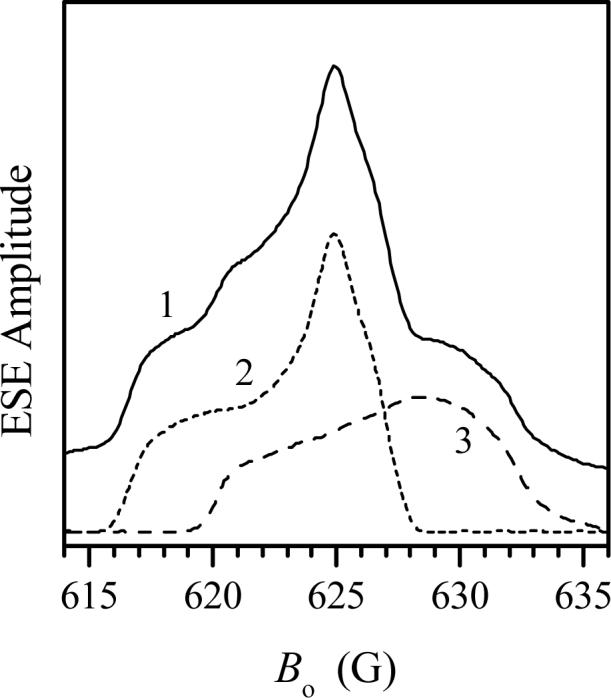

The sum combination line region of the cosine Fourier transform (FT) spectrum of the experimental integrated four-pulse ESEEM is shown in Fig. 6. It consists of three distinct lines. The most intense line is located at 2νH and is due to distant “matrix” protons. The two less intense lines, νσ1 and νσ2, are upshifted from 2νH by Δνσ1 ∼ 0.75 MHz and Δνσ2 ∼ 1.6 MHz, respectively. The anisotropic hfi constant estimated from Δνσ1 using Eq. 1 gives T⊥ ≈ 3.6 MHz, which is characteristic of the non-exchangeable α-proton of the cysteinyl residue that is directly coordinated to the molybdenum center [26]. The T⊥ value estimated from Δνσ2 is about 5.3 MHz, which is the signature of a nearby exchangeable proton customarily observed in the original hpH form [15].

Fig. 6.

Cosine FT spectrum of integrated (over the time interval τ) four-pulse ESEEM of Y343F SO in buffered H2O at pH 9.84. Experimental conditions: νmw = 6.399 GHz, magnetic field, Bo = 234 mT (high-field region of the field-sweep spectrum, where the original hpH form dominates); mw pulse durations, 15, 15, 23 and 15 ns; initial separation between the first and second pulses, τo = 200 ns; step in τ, 30 ns; number of steps in τ, 20; temperature, 21 K.

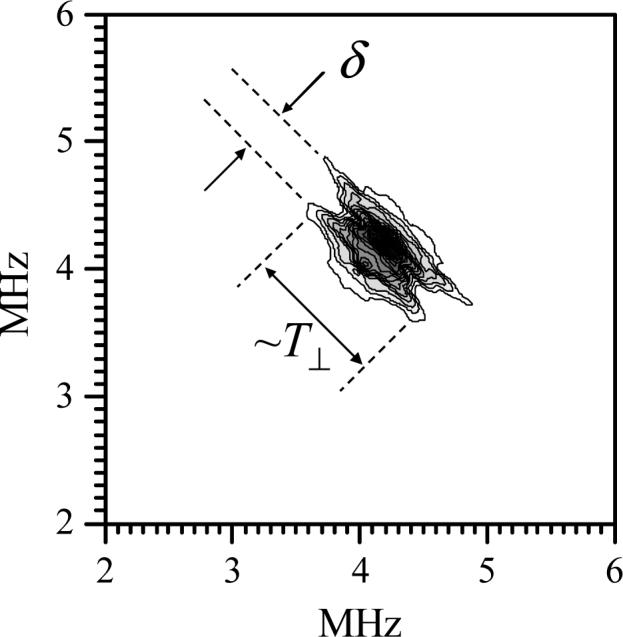

To confirm that this proton belongs to an –OH entity we performed HYSCORE measurements on this sample in buffered D2O solution, primarily at the most non-selective position (gY) of the EPR spectrum of the original hpH form. An example of such a HYSCORE spectrum (obtained as a sum of several spectra at different time intervals τ between the first and second mw pulses) is presented in Fig. 7. The “spread” of the spectrum of Fig. 7 in the direction perpendicular to the main diagonal shows the magnitude of the anisotropic hfi constant that can be roughly estimated as T⊥ ∼ 0.8 MHz for the deuteron. Rescaling this value to a proton results in T⊥ ∼ 5.2 MHz, in good agreement with the four-pulse ESEEM measurements.

Fig. 7.

HYSCORE spectrum ((++) quadrant) of Y343F SO at pD = 9.64, obtained at the position of maximum ESE intensity for the original hpH form (Fig. 4). Experimental conditions: νmw = 17.317 GHz; magnetic field, Bo = 630.5 mT; mw pulse durations, 10, 10, 11 and 10 ns; temperature, 21 K. The spectrum represents a sum of amplitude FT spectra obtained at the time intervals between the first and second mw pulses τ = 150, 300 and 350 ns. The spread of the contour plot in the direction perpendicular to the main diagonal determines the anisotropic hfi constant T⊥, while the splitting between the ridges, δ, is due to the deuterium nqi.

The splitting δ ∼ 0.3 MHz between the two ridges crossing the main diagonal of the HYSCORE spectrum of Fig. 7 is due to the deuterium nuclear quadrupole interaction (nqi). In general, the splitting for an axial nqi tensor depends on the angle ψ between the nqi tensor axis and the direction of the magnetic field, Bo, and is given by:

| (2) |

where e2Qq/h is the nuclear quadrupole coupling constant. Therefore, the lowest possible estimate for the quadrupole coupling constant that can be obtained from the observed splitting δ ≈ 0.3 MHz is e2Qq/h ≈ 0.2 MHz (corresponds to ψ = 0°). The deuterium nuclear quadrupole coupling constant is quite sensitive to the nature of the chemical fragment to which it belongs. For an OD group e2Qq/h is close to maximal and is usually within the range 0.22−0.25 MHz; for a CD group it is only ∼ 0.12 MHz, and for an ND group it is usually on the order of 0.15 MHz [31]. Thus, the deuteron observed in the HYSCORE spectrum of the original hpH component of Y343F SO belongs to an –OH group or a water molecule coordinated to the molybdenum center.

Conclusions

The variable frequency pulsed EPR studies of the Mo(V) forms of recombinant human Y343F SO show a more complex dependence upon pH than the wt enzyme. In addition to the well-known original lpH and original hpH forms observed in the wt enzyme there appears to be an additional low pH form that has no exchangeable protons and which is similar to the blocked lpH form observed in At-SO [17]. This form is uncommon for vertebrate enzymes, but also appears to be present in the human R160Q mutant [32]. Future experiments in which Y343F SO is reduced with Ti(III) citrate and with 33S-labeled sulfite should provide additional insight into the structural environment of the Mo center of Y343F SO.

In addition, Y343F SO presents a unique situation in which the pH range for the existence of the original lpH form is extended up to pH ∼10. This result indicates that the Y343F mutation increases the apparent pKa of the transition from the lpH to hpH forms by ∼2 pH units. Previous flash photolysis studies of IET between the molybdenum and heme domains of human SO showed that ket for the wt enzyme was about 10 times larger than that for Y343F SO at pH 6.0, and it was proposed that the hydrophobic phenylalanine of Y343F SO hindered direct access of water or H+ to the equatorial Mo=O group, thereby retarding efficient coupled electron-proton transfer [22].

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the NIGMS (GM-37773 to JHE and GM-00091 to KVR), and we thank the NSF (Grants DBI 9604939, BIR 9224431 and BIR-9224431) and the NIH (S10RR020959) for funds for the development of the pulsed EPR facility.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Dedicated to Professor Edward I. Solomon on the occasion of his 60th birthday

References

- 1.Feng C, Tollin G, Enemark JH. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1774:527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kisker C, Schindelin H, Pacheco A, Wehbi W, Garrett RM, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH, Rees DC. Cell. 1997;91:973. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrader N, Fischer K, Theis K, Mendel RR, Schwarz G, Kisker C. Structure. 2003;11:1251. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kappler U, Bailey S. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajagopalan KV, Johnson JL. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrett RM, Rajagopalan KV. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kisker C. In: Handbook of Metalloproteins. Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Poulos T, Wieghardt K, editors. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 2001. pp. 1121–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.George GN, Pickering IJ, Kisker C. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:2539. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hille R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 1994;1184:143. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enemark JH, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. Dalton Trans. 2006:3501. doi: 10.1039/b602919a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutteridge S, Lamy MT, Bray RC. Biochem. J. 1980;191:285. doi: 10.1042/bj1910285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamy MT, Gutteridge S, Bray RC. Biochem. J. 1980;185:397. doi: 10.1042/bj1850397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray RC, Gutteridge MT, Lamy MT, Wilkinson T. Biochem. J. 1983;211:227. doi: 10.1042/bj2110227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raitsimring AM, Pacheco A, Enemark JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:11263. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astashkin AV, Mader ML, Enemark JH, Pacheco A, Raitsimring AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5294. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM, Feng C, Johnson JL, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2002;22:421. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astashkin AV, Hood BL, Feng CJ, Hille R, Mendel RR, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13274. doi: 10.1021/bi051220y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raitsimring AM, Kappler U, Feng CJ, Astashkin AV, Enemark JH. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:7283. doi: 10.1021/ic0509534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astashkin AV, Johnson-Winters K, Klein EL, Byrne RS, Hille R, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007 January; doi: 10.1021/ja0704885. submitted. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kappler U, Bennett B, Rethmeier J, Schwarz G, Deutzmann R, McEwan AG, Dahl C. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacheco A, Hazzard JT, Tollin G, Enemark JH. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:390. doi: 10.1007/s007750050325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng CJ, Wilson HL, Hurley JK, Hazzard JT, Tollin G, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kappler U, Bailey S, Feng CJ, Honeychurch MJ, Hanson GR, Bernhardt PV, Tollin G, Enemark JH. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9696. doi: 10.1021/bi060058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enemark JH, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. In: Biological Magnetic Resonance, Vol. 29, Metals in Biology: Applications of High Resolution EPR to Metalloenzymes. Hanson GR, Berliner LJ, editors. 2006. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Temple CA, Graf TN, Rajagopalan KV. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;383:281. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM, Feng C, Johnson JL, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6109. doi: 10.1021/ja0115417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. For available pulsed EPR instrumentation, techniques and operational frequencies see: http://quiz2.chem.arizona.edu/epr/

- 28.Van Doorslaer S, Schweiger A. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;281:297. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;143:280. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikanov SA, Tsvetkov YD. Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation (ESEEM) Spectroscopy. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semin GK, Babushkina TA, Yakobson GG. Nuclear Quadrupole Resonance in Chemistry. Keter Publishing House; Jerusalem: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM, Johnson-Winters K, Wilson HL, Rajagopalan KV, Enemark JH. 2007. to be published.

- 33.George GN, Garrett RM, Graf T, Prince RC, Rajagopalan KV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4522. [Google Scholar]