Abstract

This paper uses new data from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A. FANS) to examine how neighborhood norms shape teenagers’ substance use. Specifically, it takes advantage of clustered data at the neighborhood level to relate adult neighbors’ attitudes and behavior with respect to smoking, drinking, and drugs, which we treat as norms, to teenagers’ own smoking, drinking, and drug use. We use hierarchical linear models to account for parents’ attitudes and behavior and other characteristics of individuals and families. We also investigate how the association between neighborhood norms and teen behavior depends on: (1) the strength of norms, as measured by consensus in neighbors’ attitudes and conformity in their behavior; (2) the willingness and ability of neighbors to enforce norms, for instance, by monitoring teens’ activities; and (3) the degree to which teens are exposed to their neighbors. We find little association between neighborhood norms and teen substance use, regardless of how we condition the relationship. We discuss possible theoretical and methodological explanations for this finding.

Since the publication of William Julius Wilson’s The Truly Disadvantaged (1987), there has been a renewed interest among social scientists in neighborhoods. U.S. cities have long been characterized by racial, ethnic, and economic segregation, but Wilson drew attention to increases in the geographic concentration of urban poverty starting in 1970. Ensuing studies have linked neighborhood disadvantage to a host of outcomes, including child health and development, education, labor market experience, early sex and childbearing, divorce, crime, and risk-taking (for extensive reviews, see Dietz, 2002; Gephart, 1997; Ginther, Haveman, and Wolfe, 2000; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Pebley and Sastry, 2004). This work has generated inconsistent estimates of causal effects, reflecting differences in samples, measures, and estimation strategies. Determining the causal impacts of neighborhoods has proven to be a difficult task, and advances in data and methods are only beginning catch up to interest in neighborhood context.

There is strong reason to believe that neighborhoods matter, despite inconsistent and sometimes weak empirical evidence. Three theoretical frameworks have guided much of the recent literature on neighborhood effects. The first is Wilson’s (1987) thesis about the causes and consequences of concentrated poverty. He argues that the loss of low skill jobs, the out-migration of middle class African Americans, and the lack of employed “marriageable” men have led to weaker inner-city institutions and fewer role models for conventional work and family patterns, isolating residents from mainstream society and hindering social and economic advancement. Sampson and colleagues (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls, 1997; Sampson, Morenoff, and Earls, 1999) have elaborated a second perspective focusing on how structural features of neighborhoods, including residential instability, socioeconomic disadvantage, and ethnic heterogeneity, undermine social organization and lead to crime and delinquency. In particular, social disorganization makes it harder for residents to establish trust and solidarity and to agree on common goals, thereby making it less likely that they will intervene on behalf of the community. Finally, Coleman’s (1988) social capital theory emphasizes the role of dense and overlapping social relationships in providing support and facilitating the enforcement of norms.

Neighborhood norms – generally held beliefs about acceptable behavior supported by sanctions against those who violate them – are a central element of each of these theoretical perspectives; they are also one of the most difficult to test empirically. Of the many community-level studies that have stemmed from Wilson’s work on the spatial concentration of poverty, most have relied on socioeconomic characteristics of neighborhoods to indirectly assess the role of intervening social processes (Jencks and Mayer, 1990; Furstenberg and Hughes, 1997). A growing body of research has looked directly at some of the social mechanisms hypothesized to mediate the effects of neighborhood disadvantage, including social cohesion and informal social control (e.g., Sampson et al., 1997, 1999). Very little empirical work, however, has focused on the role of norms. No study to our knowledge has examined the link between neighborhood-level norms specific to a particular set of behaviors and those behaviors themselves. Our understanding of the relationship between neighborhoods and norms thus remains limited.

We use new data from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A. FANS) to examine how norms shape teenagers’ substance use. The L.A. FANS has a clustered sample design which allows us to directly measure norms by aggregating adults’ individual reports about their substance use beliefs and patterns to the neighborhood level. The availability of clustered data on attitudes and behavior is unusual and provides a valuable opportunity to examine the role of norms in neighborhood influences on teenagers’ behavior. In contrast to prior research, we are able to link specific neighborhood-level norms (adults’ attitudes and behavior with respect to substance use) to these same individual-level outcomes (youth substance use). Moreover, our data allow us to examine other social processes expected to condition the effect of norms, including consensus in neighbors’ attitudes and conformity in their behavior, neighbors’ willingness to enforce norms, and teenagers’ exposure to their neighbors. We anticipate that the better match between our measures and conceptual model will yield stronger estimates of neighborhood effects than has been typical in the literature, which has tended to report relatively small neighborhood effects (Jencks and Mayer, 1990; Furstenberg and Hughes, 1997). We study smoking, drinking, and drug use because of their association with numerous health and behavioral outcomes, including risky sexual activity, dropping out of high school, delinquency, psychological problems, and later substance addiction (e.g., Ary et al., 1999; Cooper et al., 2003; Kandel, 2002; Mensch and Kandel, 1992; Sen, 2002). Our study contributes to two related fields of inquiry: research on the influence of community norms on individual behavior and studies of the effects of peers and other reference groups on teen substance use.

THE INFLUENCE OF NORMS ON INDIVIDUAL BEHAVIOR

Neighborhood studies have used the concept of norms to account, in part, for differences between neighborhoods in family-related behaviors, socioeconomic outcomes, and crime. There have been only a few empirical treatments, and these have focused on family-related behaviors. Brewster and colleagues (Billy, Brewster, and Grady, 1994; Brewster, 1994a, 1994b; Brewster, Billy, and Grady, 1993) examine the influence of neighborhood normative environment on adolescent sexual activity, using demographic characteristics of census tracts, namely racial composition and female labor force participation, to proxy liberal norms regarding nonmarital sex and support for economic and social success, respectively. They conclude that norms play an important role in influencing sexual behavior, but their measures are indirect. Other work has relied on more direct measures of norms, but not at the neighborhood level. Teitler and Weiss (2000) measure the normative environment of schools by aggregating schoolmates’ perceptions about the appropriate age to leave school, start drinking, start having sex, and become a parent. They find that school-level norms affect teenagers’ transition to first sex. Butler (2002) similarly operationalizes norms by aggregating individual responses to attitudinal items, but she defines community more broadly, by race, metropolitan status, and census division, areas vastly larger than the census tracts typically used in neighborhood research. She finds that welfare benefits have a greater effect on premarital childbearing in communities with more tolerant views regarding premarital sex. Finally, Casper (1992) operationalizes norms by aggregating individual responses to attitudinal items over geographic clusters defined by proximate zip code areas. Using this methodology, she finds that norms about the acceptability of cohabitation affect individuals’ likelihood of cohabiting. In sum, there is evidence that norms affect family behaviors, but measures of norms are either indirect or based on social contexts other than neighborhoods.

None of the work referenced above examines the social processes that potentially condition the effect of norms. At the neighborhood level, norms are communicated through the models neighbors provide of appropriate behavior, as well as through social interaction in which residents exchange information about their values and the expected costs of violating rules of conduct. Social interaction is thus critical in thinking about how normative context affects individual behavior. Sampson and colleagues (Sampson et al. 1997, 1999; Sampson and Raudenbush, 1999) have carefully examined social interaction at the neighborhood level. They have developed the idea of collective efficacy, defined as the “linkage of cohesion and mutual trust with shared expectations for intervening in support of neighborhood social control” (Sampson and Raudenbush, 1999, p. 612), to explain variation in neighborhood disorder given similar levels of disadvantage and residential stability. Using data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN), they have shown that collective efficacy is an important construct which can be measured reliably by aggregating individual survey responses to the neighborhood level. The PHDCN provides a model for conceptualizing and measuring key social mechanisms at the neighborhood level; none of this work, however, examines the link between social interaction, norms, and individual outcomes.

We posit that norms related to positive health behaviors are most influential in neighborhoods with high levels of collective efficacy, and we are able to test this using PHDCN-like measures of collective efficacy included in the L.A. FANS. The influence of norms on behavior should further depend on the degree of consensus in attitudes within a person’s reference group, the extent to which group members’ behavior conforms to prevailing attitudes, and individuals’ exposure to alternate beliefs about appropriate behavior. Again, prior work fails to consider these factors. The L.A. FANS has direct information about the attitudes and behavior of neighbors, as well as data on who the teenager knows in the neighborhood and whether the teenager spends time in the neighborhood, allowing us to explore how consensus, conformity, and exposure shape the influence of norms on behavior.

The design and scope of the L.A. FANS make it possible for us to examine a conceptually tighter link between neighborhood norms and individual behavior than much past work. Despite the advantages of the data, there remain challenges to any study of norms. Ambiguity about specific applications of general rules makes norms difficult for researchers to conceptualize and measure (Rossi and Rossi, 1990). For example, attitudes about the acceptability of drinking may not capture differences among groups in their attitudes about drinking alone as opposed to drinking as part of a social activity. Moreover, within the same social context there may be conflicting general norms, such as the norm of individual freedom of choice and the norm that individuals should behave responsibly to protect their health. Finally, understanding the role of norms requires measuring variation in individual perceptions of norms, when they apply, and the consequences of not conforming to them (Mason, 1983, 1991). While we are able to account for much more of the potential variation in the effect of norms on behavior than past work, we do not have information on teenagers’ perceptions of norms or the consequences of violating them. These are important, yet unmeasured, pieces of our conceptual model of the influence of norms on behavior.

SUBSTANCE USE AMONG YOUTH

Schools and Peers

There has been little emphasis on neighborhood norms in studies of youth substance use. Previous research on teenagers’ smoking, drinking, and drug use has focused on imitative behavior with respect to classmates and friends. These studies have used various strategies to assess the effects of social context on substance use: the demographic composition of the teenager’s school or neighborhood as a proxy for the prevalence of smoking (Johnson and Hoffman, 2000); friends’ behavior as reported by the teen; individual teenagers’ reports about whether their (best) friends smoke and what their friends would do if the teenager smoked around them; teenagers’ estimates of the percentage of other students in their grade who engage in the behavior of interest. Most studies of this type ignore that friends select each other based on shared values (but see Case and Katz, 1991) and that teenagers may not accurately perceive the prevalence of substance use (Kawaguchi, 2004). On the latter point, for example, Perkins and colleagues (Perkins, 2002; Perkins, Haines, and Rice, 2005) show that college students overestimate campus drinking, and that misperceptions of drinking strongly predict individual behavior.

It is important to ask how teenagers are affected by the attitudes and behavior of adults as compared to peers. Adults and peers likely matter to teens in different ways. Whereas the threat of adult sanction may be an important mechanism linking adult attitudes and behavior to teen behavior, the risk of social exclusion may be the driving force behind peer effects. Unfortunately, the theoretical and data demands for modeling neighborhood and peer effects simultaneously are high, requiring a design that takes account of teens’ choices about peers as well as sufficient numbers of cases for each combination of neighborhood and school or peer group (Kim et al., 2006). Few, if any, studies manage to do this. Given data constraints and the lack of research on how adult neighbors influence teen substance use, our analysis focuses on the influence of adults.

Individual and Family Correlates

Substance use among teens varies significantly by teens’ race/ethnicity, gender, and family structure, as well as by their parents’ attitudes and behaviors with respect to substance use (see USDHHS 1994, 1998 and Tyas and Pederson, 1998 on adolescent smoking; and Kandel, 1980 on drinking and drug use for comprehensive reviews). Smoking, drinking, and drug use tend to be more common among white teenagers than African American and Hispanic teens (Johnston, O’Maley, and Bachman, 2001; Kandel et al., 2004; USDHHS, 1994; USDHHS, 1998; Wallace and Bachman, 1991), among teens who live in single-parent households (Flewelling and Bauman, 1990; Hoffmann, 2002; Hoffmann and Johnson, 1998; Kirby, 2002), and among teens whose parents’ smoke, drink, or use drugs (Anderson and Henry, 1994; Taylor et al., 2004; Duncan et al., 1995). Furthermore, youth who believe that their parents are indifferent to smoking and/or drug use are also more likely to use these substances, regardless of their parents’ use of these substances (McDermott, 1984; Newman and Ward, 1989; Nolte, Smith, and O’Rourke, 1983). Across race/ethnic groups, boys are more likely than girls to drink and use marijuana (Wallace and Bachman, 1991), but girls are at least as likely if not somewhat more likely to smoke cigarettes (Gruber and Zinman, 2001; Kandel, 1980; Johnston et al., 2001). By contrast, socioeconomic status is not well correlated with teens’ substance use (Gruber and Zinman, 2001; Kandel, 1980; Johnston et al., 2001; USDHHS, 1998). In this paper, we control for these and other individual and family correlates of substance use among teens to estimate the effects of neighborhood-level norms.

QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH STRATEGY

Parents and other proximate adults are two key groups in the socialization of children. Our definition of neighborhood norms is based on the attitudes and behaviors of adults living in the same census tract as teenage respondents. We address two main questions: First, do neighbors’ attitudes and behavior with respect to substance use affect teenagers’ smoking, drinking, and drug use, net of the attitudes and behavior of teenagers’ parents and other individual and family-level characteristics? Second, does the effect of norms depend on social factors in the neighborhood? We expect teen substance use to increase as neighbors’ attitudes become more approving and as neighbors’ smoking, drinking, and drug use becomes more common. We expect the influence of norms to depend on: (1) the strength of norms, as measured by consensus in neighbors’ attitudes and conformity in their behavior; (2) the extent to which adults are willing and able to enforce norms about substance use; and (3) the extent to which individual youths come in contact with members of their community. Specifically, we expect that teens will be more likely to conform to norms if the norms are widely shared, if they see adult role models acting in accordance with the norms, if they will be sanctioned for not conforming, and if they have close enough ties to the community to correctly perceive the norms and sanctions.

The richness of the L.A. FANS helps us to minimize some of the most difficult methodological problems of past work on group effects. These include: (1) endogenous group membership, i.e., that children at least partially choose their social environments, which in turn accounts for associations between social context and youth outcomes; (2) unobserved heterogeneity, i.e., that there are unobserved individual or family-level characteristics that are correlated with group membership and youth outcomes; and (3) ambiguity of neighborhood boundaries (Duncan and Raudenbush, 2001; Moffitt, 2001; Small and Newman, 2001). Our focus on neighborhood effects minimizes the problem of endogenous group membership. While teens may choose their peer groups, their parents generally choose the neighborhoods in which they live (Brewster, 1994b uses a similar strategy).1 We address the problem of unobserved heterogeneity by controlling characteristics of children and their families, including parents’ attitudes and behaviors with respect to substance use. Finally, we address the ambiguity of neighborhood boundaries by testing the sensitivity of our census-tract-based results to respondents’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries.

DATA

We use data from the first wave of the L.A. FANS, which was designed explicitly to examine the effects of neighborhood characteristics on children’s well-being (Sastry et al., 2006). It is a probability sample of approximately 3,250 households from 65 neighborhoods in Los Angeles County. The clustered sample design provides large enough samples within geographic clusters to allow for measurement at the macro level, an unusual and highly valuable aspect of the L.A. FANS.

The study used a multi-stage, stratified sample design in which tracts, blocks within tracts, and then households were sampled. Tracts were stratified by the percentage of the population in the tract who were in poverty and by whether households included children under age 18. Interviews were conducted with a randomly selected adult and a randomly selected child, as well as the child’s primary caregiver and, in some cases, the child’s sibling. Field work took place during an 18-month interval from April 2000 to the end of 2001, with the exception of a small number of cases completed early in 2002. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish in person and with computer-assisted self-administered techniques. Response rates vary by type of respondent, from 89% for randomly selected adult respondents to 86% for child respondents.2 Weights adjust for unequal probabilities of sample selection and household nonresponse (Peterson et al., 2003).

The L.A. FANS sampled households from 65 of the 1,652 census tracts in Los Angeles County. Los Angeles County includes more than 9.5 million people living in an approximately 4,000 square mile area. Census tracts in Los Angeles County are of moderate size, with an average of 5,600 inhabitants (Sastry et al., 2006). Tracts were developed based on social ecological criteria and have no cross-cutting natural or man-made boundaries. They are commonly used to proxy neighborhoods and are highly salient in the daily activities of Los Angeles residents (Sastry, Pebley, and Zonta, 2002). Nonetheless, “neighborhood” is an amorphous concept (Sastry et al., 2002). Our analysis focuses on neighborhoods delineated by census tracts, but we make use of residents’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries to test the sensitivity of our results to alternative definitions.

SAMPLE AND MEASURES

The L.A. FANS includes interviews with 890 children ages 12 to 17. While the older children in this group undoubtedly have higher lifetime prevalence rates of smoking, drinking, and drug use, we expect a high proportion at all ages to have exposure to substance use. For example, a recent study by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (2005) reports that 28% of middle schoolers and 62% of high schoolers go to schools where drugs are used, kept, or sold. We found very similar results whether we included all children in our analysis or limited it to those 14 and older (i.e., of high school age). Our final sample thus includes all children ages 12 to 17 with complete data on substance use and family- and individual-level controls, totaling 838 cases. These cases are nested within 65 neighborhoods, each with an average of 15 teenagers (ranging from 5 to 25 per neighborhood). About two-thirds of our sample (N=549) was randomly selected, and the remaining one-third (N=289) is comprised of siblings residing in the household at the time of interview. Because we are looking at rare behaviors, our sample is not large enough to account for both family- and neighborhood-level clustering. Our design will consequently overestimate to some degree effects at both the family and neighborhood levels.

We discuss our measures in some detail below, and Table 1 shows descriptive statistics at the individual, family, and neighborhood levels. We provide additional information on questionnaire items and coding, as well as comparisons of substance use attitudes and behavior in the L.A. FANS and other data sources, in a technical appendix available at http://www.ccpr.ucla.edu/asp/papers.asp.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-Level Variables | ||||

| Teen smoking behavior | 1.37 | 0.68 | 1 | 4 |

| Teen drinking behavior | 1.57 | 0.89 | 1 | 4 |

| Teen drug use | 1.30 | 0.70 | 1 | 4 |

| Mother’s smoking behavior | 1.16 | 0.45 | 1 | 3 |

| Mother’s drinking behavior | 1.61 | 0.89 | 1 | 4 |

| Mother’s marijuana use | 0.03 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Mother’s disapproval of smoking | 2.45 | 0.64 | 1 | 3 |

| Mother’s disapproval of drinking | 2.38 | 0.66 | 1 | 3 |

| Mother’s disapproval of marijuana use | 2.41 | 0.67 | 1 | 3 |

| Hispanic race/ethnicity | 0.53 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| White race/ethnicity | 0.26 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Black race/ethnicity | 0.12 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 0.08 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 0.49 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Foreign born | 0.26 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Current grade in school or last completed | 9.09 | 1.77 | 5 | 13 |

| Mother is married | 0.66 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Family income (in 1000’s) | 60.46 | 90.45 | 0 | 981 |

| Mother has a college degree | 0.20 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Number of children in the household | 2.42 | 1.23 | 1 | 9 |

| Neighborhood-Level Variables | ||||

| Mean adult smoking behavior | 1.18 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.51 |

| Mean adult drinking behavior | 1.93 | 0.22 | 1.50 | 2.62 |

| Mean adult marijuana use | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Mean adult disapproval of smoking | 2.32 | 0.15 | 1.88 | 2.59 |

| Mean adult disapproval of drinking | 2.18 | 0.20 | 1.68 | 2.51 |

| Mean adult disapproval of marijuana use | 2.21 | 0.25 | 1.36 | 2.69 |

| High on adult smoking | 0.32 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| High on adult drinking | 0.39 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| High on adult marijuana use | 0.32 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| High on adult disapproval of smoking | 0.29 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| High on adult disapproval of drinking | 0.09 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| High on adult disapproval of marijuana use | 0.27 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| High child-centered social control | 0.42 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| More than 40% foreign born | 0.49 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| More than 40% owner-occupied housing | 0.49 | -- | 0 | 1 |

Note: Sample size is 838 individuals. Means and proportions are weighted.

Note: Sample size is 65 neighborhoods. Data are unweighted.

Intensity of Substance Use among Teenagers

Outcome variables are based on teenagers’ own reports about their smoking, drinking, and drug use (including marijuana, cocaine, speed, etc.). We construct measures of intensity of use ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (most intense use). For example, the intensity of smoking is coded 1 if the teenager never had a cigarette; 2 if he or she had tried one, but not in the past 30 days; 3 if he or she had a cigarette in the past 30 days; and 4 if he or she usually had more than one cigarette on the days he or she smoked.3 Because the processes predicting ever having tried a substance may differ from heavy use of a substance, we tested the sensitivity of our results to our measurement of substance use. We created a dichotomous variable indicating whether the teenager ever tried cigarettes, alcohol, or drugs, and our results were very similar to those we report below.4

The reliability of young people’s reports of smoking, drinking, and drug are reasonably high and do not appear to vary by gender, race-ethnicity, or grade in school (Brener et al., 2002; Johnston et al., 2001). Self reports about substance use have substantial construct validity (Johnston et al., 2001). And although external criteria for evaluating the validity of self-reported drug use are difficult to obtain, comparisons of smoking self reports and serum cotinine levels reveal few discrepancies (Wagenknecht et al., 1992). Finally, self reports about less stigmatized drugs appear to have greater validity than those of other drugs (Harrison and Hughes, 1997).

Neighborhood-Level Characteristics

Most research on neighborhood effects is constrained to rely solely on structural features of neighborhoods derived from census data. By contrast, the clustered design of the L.A. FANS allows us to examine characteristics of the normative and social relationships contained within neighborhoods. The L.A. FANS conducted interviews with 2,619 randomly selected adults, some of whom were also children’s primary care givers (usually mothers, and thus we refer to them as such). To create neighborhood-level indicators of attitudes, behavior, and perceptions of social relationships, we aggregate adult reports on these items to the census tract level. We then assign each child his or her own neighborhood score, excluding the child’s own mother from the aggregated neighborhood responses to preserve the distinction between parent and neighborhood effects. The number of adults in each of the 65 sample neighborhoods ranges from 27 to 57, with an average of 40. In addition to social characteristics of neighborhoods, we control for structural features derived from census data matched to sample tracts.

Norms

Norms are taken to be the beliefs and practices of neighbors with respect to the teen behaviors of interest: smoking, drinking, and drug use. All randomly selected adults are asked about their disapproval of these behaviors, as well as their current use of cigarettes and alcohol. We measure the intensity of neighbors’ smoking (on a scale from 1 to 3) and drinking (on a scale from 1 to 4). Questions about drug use are more limited; we construct a dichotomous indicator of marijuana use in the past 30 days.5 Unlike the teen measures of substance use, these relate only to current or recent substance use, as past use is less likely to be important in the socialization of children.

Our measurement of attitudes is limited in two ways. First, attitude items may overstate consensus about the appropriateness of substance use. Attitudes are measured by a single item with responses ranging from 1 (“don’t disapprove) to 3 (“strongly disapprove”). Response dimensions such as these elicit less variation in respondents’ reports than scales with less absolute end points, such as “very little” to “very much” (Wyatt and Meyers, 1987). Second, respondents report only on their disapproval of adults’ smoking, drinking, and drug use, as opposed to teenagers’. Because adults are less likely to disapprove of substance use among other adults than among teenagers, our indicators of neighborhood norms are likely to give a weaker signal of the normative environment than if attitude questions referred to the behavior of those under 18. Nonetheless, it is very likely that those who disapprove of adults’ substance use would also disapprove of teenagers’ substance use.

Despite the potential importance of collective socialization for child outcomes, the literature offers little guidance on how to operationalize this concept. Further, past work is not very clear about the processes through which children are affected by adults who are not in their family. We examine two distinct hypotheses with respect to neighbors’ attitudes and behaviors. First, we assume that the normative climate is best described by the typical neighbor, and we examine the average level of substance use and the average level of disapproval in the neighborhood. Second, we place greater weight on consensus and conformity in influencing behavior and create indicators for neighborhoods in which there is a high level of substance use (neighborhoods in the top quartile of average substance use) and high level of disapproval (more than half of all neighbors strongly disapproving). We also considered whether to model a single norm about use of any substances or separate norms relating specifically to smoking, drinking, and drug use. Correlations among neighbors’ smoking, drinking, and marijuana use did not move in unison (see the online technical appendix), which strongly suggests separate norms. We thus examine the influence of norms about smoking on teenagers’ smoking behavior, those about drinking on teenagers’ drinking behavior, and those about marijuana use on teenagers’ drug behavior.

Enforcement of norms

We expect that the effect of norms depends on the ability of neighbors to enforce them, for instance, by monitoring teens’ activities. We draw on work by Sampson and colleagues (especially Sampson et al., 1999) to investigate this hypothesis. This work highlights three dimensions of neighborhood collective efficacy that affect the lives of children: (1) the maintenance of intergenerational ties; (2) the reciprocal exchange of help; and (3) the collective willingness to intervene on behalf of children or “child-centered social control.” The L.A. FANS borrowed questions from the PHDCN to tap these dimensions of collective efficacy, and we tested the role of each in conditioning the influence of neighbors’ attitudes and behavior on teen substance use. Only child-centered social control, which has a certain face validity for this process, was statistically significant in conditioning neighborhood norms, and thus it is the only dimension of collective efficacy that we include in our final models. It is measured by averaging responses (ranging from 1 to 5) to three questions about the likelihood that neighbors would do something if children were (1) hanging out on a street corner during school hours, (2) spray-painting graffiti on a local building, or (3) showing disrespect to an adult. Neighborhoods are coded high on this dimension if most adults in the neighborhood average 4 or higher on these questions. Just over 40% of neighborhoods score high on child-centered social control.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Social structural characteristics play a role in the formation and enforcement of norms. For example, ethnic heterogeneity, immigrant concentration (which may increase ethnic and linguistic heterogeneity), and residential instability may weaken value consensus and adult networks, and thus impede the realization of common goals. Poverty undermines resources, trust, and certainty important to collective action. And high concentrations of children create a high child care burden for the community. These neighborhood characteristics are all associated with collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 1997, 1999; Sampson and Morenoff, 1997; Sampson and Raudenbush, 1999; Sampson, 1992). To avoid confounding the effects of social structure, norms, and collective efficacy, we include indicators for neighborhoods with high proportions (greater than 40%) of foreign-born residents and owner-occupied housing. Although we include only two indicators of neighborhood heterogeneity and stability in our models, we explored the roles of race/ethnic composition, age composition, poverty level, and residential tenure. Adding these indicators of neighborhood composition did not alter our conclusions.

Individual- and Family-Level Measures

Exposure to norms

We expect the effect of norms to depend on the degree to which teenagers’ are exposed to them. We construct a composite measure of teenagers’ exposure to their neighborhoods, combining information from four questions from the child interview: whether teens know most adults in the neighborhood, whether they know most other teens in the neighborhood, whether any of their best friends live in the neighborhood, and whether they are able to walk most places they go with their friends. About 60% of the teens in our sample responded yes to at least two of these items; we code them as having a high level exposure to their neighborhood. This measure of exposure includes components that depend on teenagers’ choices, for instance, choosing best friends who live in the neighborhood. Selectivity may bias to some extent our estimation of the causal effects of exposure on the relationship between norms and teenagers’ substance use.

Perceptions of neighborhood boundaries

There is considerable variation in respondents’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries (Sastry et al., 2002). Teenagers in the L.A. FANS were asked: “When you are talking to someone about your neighborhood, what do you mean?” We construct an indicator for those who define their neighborhood as no bigger than several blocks or streets in each direction, a definition most closely corresponding to tracts. We use this information to test whether neighborhood effects are the same for those whose definitions correspond to tracts (about 75%) as compared to those who view their neighborhoods in broader terms.

Family and sociodemographic controls

Merging information from the child and primary caregiver interviews gives us a rich array of family- and individual-level controls. We control for the attitudes and behaviors of teenagers’ mothers, as well as other socioeconomic characteristics that may account for both the neighborhoods in which children live and their use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs. Mothers’ smoking, drinking, and drug use are measured in the same way as neighbors’, that is, taking account of intensity of current use.6 Mothers’ attitudes about smoking, drinking, and marijuana use are also measured in the same way as neighbors’; they are based on three questions gauging disapproval and range from 1 (“do not disapprove”) to 3 (“strongly disapprove”). Our models control for teenager’s race/ethnicity, sex, nativity status, and grade, as well as mother’s marital status, family income, mother’s education, and the number of children in the household. These account for joint variation in the determinants of substance use and the factors that sort individuals into neighborhoods.

METHODS

Our data have a hierarchical structure, with teenagers nested within neighborhoods. We conduct descriptive analyses that build to more complex hierarchical linear models to examine the influence of neighborhood norms on teen behavior. Hierarchical linear models are designed to analyze variables from different levels simultaneously and to correct for dependencies in the data due to clustering (Hox, 2002; Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). Given individual i in neighborhood j and substance k, we specify the relationship between teen substance use Yk and neighborhood norms, controlling for other neighborhood characteristics, mother’s use of and attitudes about substance k, and individual-level sociodemographic controls. Our model takes the following form:

Level 1 (within neighborhood model)

Level 2 (between neighborhood model)

where β0 jk is the expected value of teen’s use of substance k for neighborhood j when all covariates are equal to zero; β1 jk and β2 jk represent the effects of mother’s use of substance k and disapproval of use of substance k, respectively, for neighborhood j;7 β3 jkp is a set of p coefficients associated with family- and individual-level sociodemographic controls for neighborhood j and substance k; and eijk is the deviation of teenager i’s substance use score from the expected value based on the regression model for neighborhood j and substance k. At level two, γ01k and γ02k represent the effects of neighbors’ use and disapproval of the use of substance k, respectively, on teen’s use of substance k in neighborhood j; γ03k is the coefficient associated with the enforcement of neighborhood norms, namely child-centered social control; γ04kq is a set of q coefficients associated with neighborhood structural characteristics; and the parameter μ0 jk captures the deviation of the mean teen use of substance k for neighborhood j from the average across neighborhoods. Analogous to the within-neighborhood deviations ( eijk ), the between-neighborhood deviations (μ0 jk ) are assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 and variance of τ00k . This method allows us to test whether the average level of teen use of substance k varies significantly across neighborhoods conditional on covariates in the model (H0: τ00k = 0). It also allows us to test whether our key variables of interest – neighbors’ attitudes and behavior – are associated with the level of teen substance use in a given neighborhood net of individual predictors. Models are estimated using HLM 5.05 (Raudenbush et al. 2001).

We test whether the influence of norms depends on neighbors’ willingness and ability to enforce them by adding an interaction at the neighborhood level between norms and child-centered social control. We examine whether the association between norms and behavior is stronger among teens who have a high degree of exposure to their neighborhoods or among those whose perceptions of neighborhood boundaries most closely correspond to census tracts. We test these by including cross-level interactions between individual-level exposure and perceived boundaries and neighborhood-level norms (i.e., we allow the slopes of exposure and perceived boundaries to vary as a function of neighbors’ attitudes and behavior).

RESULTS

Conventional approaches to neighborhood effects often start with a comparison of variation within and between neighborhoods. The intraclass correlation from an intercept-only hierarchical model provides such an estimate of variation in teenagers’ substance use (variance components not shown). The intraclass correlation (ICC) is the between-neighborhood variance divided by total variance for substance k: Var(μ0 jk )/(Var(μ0 jk ) + Var( eijk )). The ICC, or share of total variance that is between neighborhoods, is just 1% for smoking. Indeed, the between-neighborhood variation in smoking is not statistically significant. The share of between-neighborhood variance in drinking and drug use is somewhat larger, 5 and 2%, respectively; these numbers are statistically significant. In sum, upwards of 95% of the variation in substance use among teenagers is within neighborhoods.

Others report similarly low levels of between-group variance in teen substance use. Based on data on high school students from the 1992 Monitoring the Future Project (MTF), Bachman et al. (2001) report between-school variation of 3 to 4% in smoking (depending on the unit of measurement), 5% in drinking, 4 to 6% in marijuana use, and less than 2% in other illicit drugs. An update using the 1999 MTF reports similar figures for daily cigarette use and heavy drinking (Kumar et al., 2002). Although there is less work on neighborhoods, what does exist also reports low ICC’s for substance use (Cook, Shagle, and Deg irmenciog lu, 1997). This is true of other outcomes at the neighborhood level, including crime, delinquency, and educational attainment (Cook et al., 1997; Sampson, 2001; Duncan and Raudenbush, 2001). Nonetheless, Duncan and Raudenbush (2001, p. 126) show that small correlations between neighbors (i.e., low ICC’s) are not inconsistent with substantial neighborhood effects.

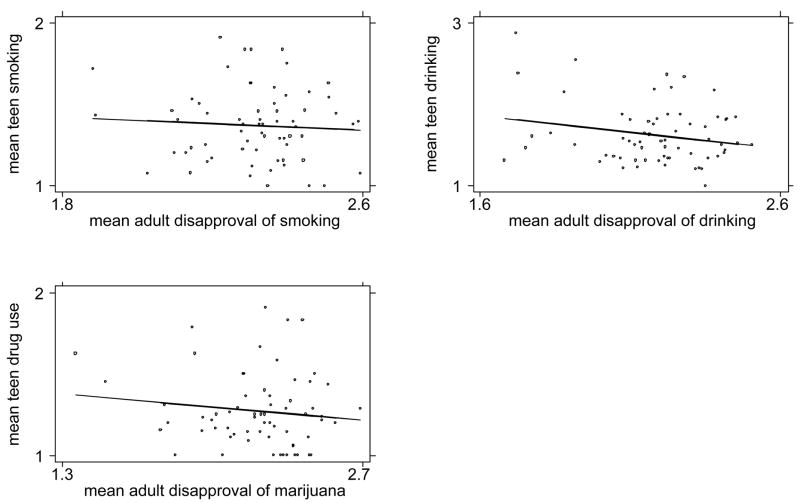

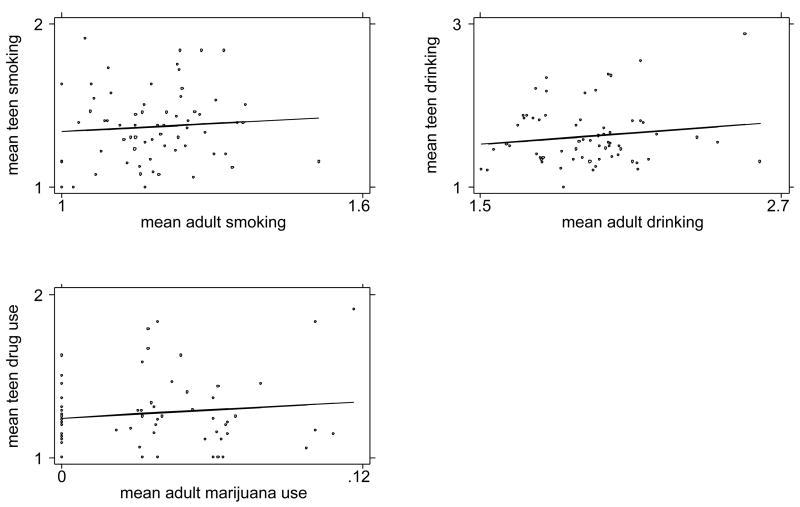

Figures 1 and 2 show how teenagers’ behavior at the neighborhood level relates to neighborhood norms. Figure 1 shows the mean level of teen smoking, drinking, and drug use in the neighborhood on the y-axes and the mean level of disapproval among adult neighbors on the x-axes. Although in each case, the relationship is in the expected direction, with teen substance use negatively related to neighbors’ disapproval, the relationships appear to be weak, particularly for smoking. Figure 2 shows the relationship between teen smoking, drinking, and drug use in the neighborhood and adult neighbors’ smoking, drinking, and marijuana use. Again, relationships are in the expected direction, with teen substance use positively associated with neighbors’ use, but the associations appear weak.

Figure 1.

Neighborhood-Level Associations between Teen Substance Use and Adult Disapproval of Substance Use

Figure 2.

Neighborhood-Level Associations between Teen Substance Use and Adult Substance Use

Table 2 reports coefficients from a series of descriptive models of teen substance use. Model 1 includes our key explanatory variables: neighbors’ average level of disapproval of substance use and their average behavior with respect to smoking, drinking, and marijuana use. The variables are signed in the expected directions, but in no case are they statistically significant. Tests of the joint significance of neighbors’ attitudes and behavior fail statistical significance. In analyses not shown here, we also investigated whether neighborhoods in which adults’ attitudes and behaviors were consistent, for instance, high disapproval and low usage, reduced teenagers’ substance use, but the interaction of attitudes and behavior was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Descriptive Models of Teenagers’ Substance Use and Neighborhood Norms

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.37 | 0.53 ** | 1.35 | 0.03 *** | 0.87 | 0.53 |

| Neighborhood-level predictors | ||||||

| Mean adult smoking behavior | 0.11 | 0.27 | −0.01 | 0.29 | ||

| Mean adult disapproval of smoking | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.18 | ||

| High smoking behavior | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

| High disapproval | 0.00 | 0.06 | ||||

| High child-centered social control (csc) | 1.43 | 0.69 ** | ||||

| High csc x mean disapproval | −0.63 | 0.30 ** | ||||

| Variance components | ||||||

| Within neighborhoods | 0.453 | 0.453 | 0.453 | |||

| Between neighborhoods | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.001 | |||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.24 | 0.90 ** | 1.60 | 0.05 *** | 2.90 | 1.44 ** |

| Neighborhood-level predictors | ||||||

| Mean adult drinking behavior | 0.01 | 0.24 | −0.02 | 0.22 | ||

| Mean adult disapproval of drinking | −0.31 | 0.28 | −0.57 | 0.58 | ||

| High drinking behavior | −0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| High disapproval | −0.01 | 0.08 | ||||

| High child-centered social control (csc) | −0.78 | 1.45 | ||||

| High csc x mean disapproval | 0.36 | 0.65 | ||||

| Variance components | ||||||

| Within neighborhoods | 0.766 | 0.767 | 0.766 | |||

| Between neighborhoods | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.037 | |||

| Drug use | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.44 | 0.23 *** | 1.26 | 0.03 *** | 1.63 | 0.31 *** |

| Neighborhood-level predictors | ||||||

| Mean adult marijuana use | 0.49 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 0.96 | ||

| Mean disapproval of marijuana use | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.18 | 0.13 | ||

| High marijuana use | −0.06 | 0.06 | ||||

| High disapproval | 0.03 | 0.06 | ||||

| High child-centered social control (csc) | −0.37 | 0.41 | ||||

| High csc × mean disapproval | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||||

| Variance components | ||||||

| Within neighborhoods | 0.376 | 0.377 | 0.376 | |||

| Between neighborhoods | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |||

Note:

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01.

Model 2 similarly examines the influence of neighborhood attitudes and behavior, but codes them to test the importance of consensus in neighbors’ beliefs and behavior. It includes two dummy variables, one indicating whether at least half the neighbors strongly disapprove of smoking, drinking, and marijuana use, and the other indicating whether the neighborhood is in the top quartile of average smoking, drinking, and drug use. These coefficients are very close to zero, and in no case are they statistically significant (independently or jointly). Thus we find no association between teen substance use and neighborhood attitudes and behavior, irrespective of whether we examine typical beliefs and behaviors or single out neighborhoods with a high degree of consensus and consistency in their attitudes and behavior.

Model 3 examines whether the influence of norms depends on the degree to which adults in the neighborhood are able and willing to enforce the norms. It includes an interaction between neighborhoods scoring high on child-centered social control and disapproval of substance use. This interaction is not statistically significant for drinking or drug use, but it is for smoking. Its sign is in the expected direction, suggesting that neighbors’ disapproval of smoking is more strongly, negatively associated with teen smoking in neighborhoods high on child-centered social control.

Finally, we tested whether the influence of norms depends on either teenagers’ exposure to their neighborhoods or their perceptions of neighborhood boundaries (results not shown). We expected that teenagers with dense social ties in the neighborhood would be most responsive to the beliefs and behaviors of neighbors. But the cross-level interaction between teenagers’ exposure and neighborhood norms was not statistically significant. We also tested the cross-level interaction between teenagers’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries and neighborhood norms, with the expectation that norms would have a greater impact on teens whose perceptions of neighborhood boundaries were consistent with census tracts. These interactions were likewise not statistically significant.

Table 3 reports full models of the association between neighborhood norms and teen substance use, controlling for additional neighborhood- and individual-level variables. The smoking model includes the interaction between child-centered social control and neighborhood norms (i.e., it builds on Model 3). The drinking and drug use models do not include this term, since it was not statistically significant in our pared down models (i.e., these build on Model 1). Accounting for family- and individual-level controls, the interaction between child-centered social control and neighbors’ disapproval remains statistically significant in the smoking model, and the magnitude of the association remains nearly the same. As in the pared down models, none of the other neighborhood-level variables is significantly associated with teen drinking or drug use.

Table 3.

Full Models of Teenagers’ Substance Use

| Smoking | Drinking | Drug Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |

| Intercept | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.28 *** |

| Neighborhood-level predictors | ||||||

| Mean adult behaviora | −0.03 | 0.26 | −0.03 | 0.23 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Mean disapproval of behaviora | 0.16 | 0.16 | −0.24 | 0.24 | −0.07 | 0.13 |

| High child-centered social control (csc) | 1.46 | 0.59 ** | ||||

| High csc x disapproval | −0.65 | 0.26 ** | ||||

| More than 40% foreign born | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| More than 40% owner-occupied housing | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Person-level predictors | ||||||

| Mother’s behaviora,b | 0.10 | 0.05 ** | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| Mother’s disapproval of behaviora,b | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.05 * | −0.08 | 0.03 ** |

| Hispanic race/ethnicity (v. White) | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.07 |

| Black race/ethnicity (v. White) | −0.20 | 0.10 ** | −0.34 | 0.12 *** | −0.10 | 0.09 |

| Other race/ethnicity (v. White) | −0.28 | 0.09 *** | −0.54 | 0.13 *** | −0.11 | 0.09 |

| Female | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.06 * | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Foreign-born | 0.26 | 0.09 *** | 0.15 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Female x foreign-born | −0.34 | 0.11 *** | −0.44 | 0.12 *** | -0.08 | 0.09 |

| Current grade in school or last completed | 0.09 | 0.01 *** | 0.16 | 0.02 *** | 0.08 | 0.01 *** |

| Mother is married | −0.15 | 0.06 *** | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.05 ** |

| Family income (in 1000’s) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mother has a college degree | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Number of children in the household | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Variance components | ||||||

| Within neighborhoods | 0.409 | 0.656 | 0.349 | |||

| Between neighborhoods | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.007 | |||

Notes:

This behavior refers to the same one being modeled; e.g., when teen smoking is the predictor, adult/mother smoking and adult/mother disapproval of smoking are the explanatory variables.

Covariate is deviated from the neighborhood mean.

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01.

Table 4 summarizes results of the final smoking model. It shows predicted values of teen smoking as child-centered social control and neighborhood norms change, holding all other variables at their mean values. Specifically, we show the predicted value of teen smoking, varying child-centered social control from low (0) to high (1) and varying disapproval of smoking from low (2, which is at the very bottom of the distribution of neighborhood attitude scores) to high (2.5, which is the very top of the distribution). For neighborhoods low on child-centered social control, there is little association between disapproval and teen smoking. For neighborhoods high on child-centered social control, disapproval is associated with reduced teen smoking, as hypothesized. The predicted value of teen smoking drops from 1.48 when disapproval is low to 1.24 when disapproval is high (recall that smoking behavior is coded “1” if the teenager has never smoked at all and “2” if the teen has tried smoking, but has not smoked in the past 30 days). That is, when disapproval moves from the bottom to the top of the distribution of neighborhood attitudes, teen smoking declines .24 points, or about a third of a standard deviation. To put this into context, teen smoking declines .10 points for every 1-point drop in mother’s smoking (Table 3). This translates into a .10 decline in teen smoking when mother’s smoking goes from less than a pack a day to nothing and a .20 decline when mother’s smoking goes from a pack or more a day to nothing.

Table 4.

Predicted Values of Teen Smoking, Varying Neighbors’ Disapproval and Child-Centered Social Control (CSC)

| Disapproval | ||

|---|---|---|

| Low (2.0) | High (2.5) | |

| Child-Centered Social Control | ||

| Low (0) | 1.33 | 1.40 |

| High (1) | 1.48 | 1.24 |

Note : Predictions based on the full model (Table 3), holding all other variables at their mean values.

Although we did not specifically hypothesize about the main effect of child-centered social control, these results are worth noting. Table 4 shows that in neighborhoods high on disapproval, teen smoking is lower when child-centered social control is high (compare 1.24 vs. 1.40). Perhaps less intuitively, it also shows that in neighborhoods low on disapproval, teen smoking is higher when child-centered social control is high (compare 1.48 vs. 1.33). This finding is consistent with one of the criticisms of research on social capital; namely, that it does not differentiate between negative and positive goals (Sampson et al. 1999, p. 636). Close ties may make it possible for neighbors to pressure and sanction others into conforming to prevailing norms, whatever those norms are. In neighborhoods where there is little disapproval of smoking, social relationships may facilitate the transmission of smoking to other neighborhood adults and teenagers. By contrast, in neighborhoods where there is high disapproval of smoking, these same social ties may limit neighborhood smoking.

Our findings (in Table 3) on the relationship between individual and family characteristics and teenagers’ substance use are similar to those reported by others. At the family level, we find that either mothers’ attitudes or behaviors with respect to substance use are always significantly associated with teen substance use. A mother’s smoking is positively associated with teen smoking, and her disapproval of drinking and marijuana use is negatively associated with teen alcohol use and teen drug use, respectively. Living with a married mother is associated with lower levels of substance use (results are not statistically significant for drinking). Family income, mother’s schooling, and number of children in the household are not significantly associated with teen smoking, drinking, or drug use. The lack of association between family socioeconomic status and teen substance use is consistent with other work (Gruber and Zinman, 2001; Kandel, 1980; Johnston et al., 2001; USDHHS, 1998).

White teens have higher rates of smoking and drinking, particularly compared to blacks and “others,” who are predominantly Asian. Teens are much more likely to smoke, drink, and use drugs as they progress through school. For both smoking and drinking, there is a strong interaction between sex and nativity status: foreign-born girls have relatively low levels of smoking and drinking, whereas foreign-born boys have relatively high levels. Because work on the experimental Moving to Opportunity study (e.g., Kling, Liebman, and Katz, 2005) found important sex interactions in the effects of neighborhoods on teenagers, we tested cross-level interactions between teenagers’ sex and neighborhood norms; we found no differences between girls and boys in the effects of norms.

DISCUSSION

The L.A. FANS allows us to measure social processes linking neighborhoods and teen outcomes, thus taking us further than much past research on neighborhood effects. In contrast to prior research, we are able to link specific neighborhood-level norms (adults’ attitudes and behavior with respect to substance use) to these same individual-level outcomes (youth substance use). Moreover, our data allow us to examine other social processes expected to condition the effect of norms, including consensus in neighbors’ attitudes and behavior, neighbors’ willingness to enforce norms, and teenagers’ exposure to their neighbors. We find some evidence that norms affect teenagers’ behavior in neighborhoods in which residents are willing to enforce rules of conduct. Namely, in neighborhoods with high levels of child-centered social control, we find that teenagers are less likely to smoke as neighbors’ disapproval of smoking increases. We find no evidence of effects of neighborhood norms, however, on drinking or drug use, even among youths who know most people in the neighborhood and spend a lot of time in the neighborhood. Nor do we find effects when we condition the influence of norms on teenagers’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries.

The sole significant association between teen substance use and norms is in the smoking model. If smoking is seen as more detrimental to health than alcohol or marijuana use, adults may be more vigilant in their enforcement of norms against it. Smoking may also be more visible than either drinking or marijuana use. Whereas drinking is regulated and marijuana is illegal, people can smoke on porches, sidewalks, and neighborhood parks, in plain view of others. This visibility means that adults may be more aware of teens’ smoking than they are of their drinking or drug use, and thus more able to sanction nonconforming behavior. It also means that teenagers may be better able to perceive neighborhood norms about smoking than those about other substances.

There are other possible explanations for the weak estimated effects of neighborhood norms on teenagers’ behavior. First, the direction of causation may be from teen substance use to norms. Neighbors may strongly disapprove of substance use if they perceive these behaviors to be a problem in their neighborhood. Empirically this would result in an inverse association between norms and substance use. If both processes are at work – i.e., the normative climate affects teen substance use and neighbors’ attitudes change as a result of bad behavior around them – we would see little association between norms and substance use the way we are modeling it.

Second, our measure of norms may give a weak signal of the normative environment. We are not modeling the psychosocial process that mediates between individual-level and group-level variables. For example, adult attitudes and sanctions may not be accurately perceived by teenagers, even those who have a high degree of exposure to their neighborhoods. Prior work shows that young adults misperceive local norms, and that their behavior tends to be affected more by their (mis)perceptions than by actual beliefs and practices (Perkins et al., 2005). The attitude questions we use to measure norms may also contribute to this problem. The available items refer to neighbors’ disapproval of substance use among other adults. While we assume these are highly correlated with neighbors’ disapproval of teen behavior, they likely underestimate the level of disapproval for teens.

Finally, substance use may be a normative part of the transition to adulthood (e.g., Ennett et al., 1997). It is not strongly patterned by socioeconomic status like other risky behaviors and school achievement, and it may not be strongly patterned by neighborhoods. Alternatively, substance use may be related to neighborhoods in ways that we cannot distinguish in our data. For example, the processes leading to early substance use may be different from those related to later use; likewise, the processes leading to heavy use may be different from those related to experimentation. When in their developmental stage teenagers first use substances and the intensity of their use may have important implications for whether substance use is a normative part of growing up, or an antecedent of negative health and social consequences. Although we do not find age differences in the effects of norms on teens’ substance use, these processes are better examined using longitudinal data. Followup data from the second wave of the L.A. FANS now in the field will provide a valuable opportunity to investigate these issues further.

Acknowledgments

The first author received funding for this project from a Haynes Foundation Faculty Fellowship and Grant Number K01 HD42690 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences; additional support was provided by the California Center for Population Research at UCLA, which receives core support from Grant No. R24 HD41022 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank participants of the L.A. FANS Working Group and the IRP Summer Research Workshop for helpful comments on earlier drafts, especially Joseph Hotz, Ariel Kalil, Robert Mare, Lincoln Quillian, and Jeffrey Smith. We are also grateful to Eric Grodsky for methodological advice and to the editor of Social Science Research and the anonymous reviewers for many useful suggestions.

Footnotes

Parents, however, may choose neighborhoods to improve the conditions in which children live. Depending on whether moving to a new neighborhood helps the child and when in the process the family is observed, this could minimize the association between neighborhood disapproval and teens’ substance use, for instance if the teen is smoking or drinking and the parents move to a neighborhood with strong disapproval to try to correct this behavior (for a discussion of residential selection, see Kling, Liebman, and Katz, 2005).

Response rates also depend on assumptions about whether households that were not screened for sample selection were eligible for the study. If households with unknown eligibility have the same percentage eligible as screened households, the response rates are considerably lower, just over 60% (Sastry and Pebley, 2003).

See the technical appendix for details on the coding of drinking and drug use and for a comparison of the substance use reports of teenagers in the L.A. FANS to three other data sources.

We also constructed a multi-category outcome indicating no use vs. some use vs. heavy use, but the data were too thin to examine neighborhood-level variation.

Although marijuana attitudes are asked of all adults, marijuana use is asked only of primary caregivers, and there is just one question referring to use in the past 30 days, precluding an investigation of intensity of use. For this one behavior, the responses of primary caregivers (N=1,945) are used to stand in for adult behavior. This is not ideal, particularly because mothers have lower rates of substance use than the overall adult population.

We expect that past use is less likely to provide a role model for teenagers, although this depends on when mothers who ever used these substances stopped using them. In this analysis we ignore any physiological consequences of mothers’ prenatal smoking and drinking for teenagers’ substance use.

Both of these enter the model as deviations from the neighborhood mean since corresponding variables are found in the level 2 model. Results were the same whether we used raw scores or mean-deviated scores.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kelly Musick, University of Southern California.

Judith A. Seltzer, University of California, Los Angeles

Christine R. Schwartz, University of Wisconsin, Madison

References

- Anderson AR, Henry CS. Family system characteristics and parental behaviors as predictors of adolescent substance use. Adolescence. 1994;29:405–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. Adolescent problem behavior: The influence of parents and peers. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1999;37:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper 54. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2001. The monitoring the future project after twenty-seven years: Design and procedures. Retrieved March 18, 2004 ( http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/occ54.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Billy JOG, Brewster KL, Grady WR. Community effects on adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(2):387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen S, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KL. Neighborhood context and the transition to sexual activity among young black women. Demography. 1994a;31(4):603–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KL. Race differences in sexual activity among adolescent women: The role of neighborhood characteristics. American Sociological Review. 1994b;59(3):408–424. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KL, Billy JOG, Grady WR. Social context and adolescent behavior: The impact of community on the transition to sexual activity. Social Forces. 1993;71(3):713–740. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC. Welfare, premarital childbearing, and the role of normative climate: 1968–1994. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(2):295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Case AC, Katz LF. NBER Working Paper No. 3705. National Bureau of Economic Research; 1991. The company you keep: The effects of family and neighborhood on disadvantaged youths. [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM. Office of Population Research Working Paper No. 92–9. Princeton University; 1992. Community norms and cohabitation: Effects of level and degree of consensus. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Shagle SC, Deg irmenciog lu SM. Capturing social process for testing mediational models of neighborhood effects. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol. 2: Policy Implications in Studying Neighborhoods. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. pp. 94–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Wood PK, Orcutt HK, Albino A. Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):390–410. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz RD. The estimation of neighborhood effects in the social sciences: An interdisciplinary approach. Social Science Research. 2002;31(4):539–575. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H, Stoolmiller M. An analysis of the relationship between parent and adolescent marijuana use via generalized estimating equation methodology. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30(3):317–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3003_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhoods and adolescent development: How can we determine the links? In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does It Take a Village? Community Effects on Children, Adolescents, and Families. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park; 2001. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Flewelling RL, Lindrooth RC, Norton EC. School and neighborhood characteristics associated with school rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(1):55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling RL, Bauman KE. Family structure as a predictor of initial substance use and sexual intercourse in early adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(1):171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Hughes ME. The influence of neighborhoods on children’s development: A theoretical perspective and research agenda. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol. 2: Policy Implications in Studying Neighborhoods. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gephart Martha A. Neighborhoods and communities as contexts for development. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol. 1: Context and Consequences for Children. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ginther D, Haveman R, Wolfe B. Neighborhood attributes as determinants of children’s outcomes: How robust are the relationships? Journal of Human Resources. 2000;35(4):603–642. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Zinman J. Youth smoking in the United States: Evidence and implications. In: Gruber J, editor. Risky Behavior Among Youth. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2001. pp. 69–120. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L, Hughes A.Harrison L, Hughes A.1997Introduction – The validity of self-reported drug use: Improving the accuracy of survey estimates The Validity of Self-Reported Drug Use: Improving the Accuracy of Survey Estimates NIDA Research Monograph 167, NIH Publication No. 97–4147. National Institute of Drug Use. Retrieved March 18, 2004 (http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph167/download167.html)1–16. [PubMed]

- Hoffmann JP. The community context of family structure and adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Johnson RA. A national portrait of family structure and adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60(3):633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Mayer SE. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In: Lynn LE Jr, McGeary MGH, editors. Inner City Poverty in the United States. National Academy Press; Washington DC: 1990. pp. 111–186. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Hoffmann JP. Adolescent cigarette smoking in US racial/ethnic subgroups: Findings from the National Education Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(4):392–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2000. Volume 1: Secondary School Students (NIH Publication No. 01–4924) National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2001 Retrieved March 18, 2004 ( http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/vol1_2000.pdf)

- Kandel DB. Drug and drinking behavior among youth. Annual Review of Sociology. 1980;6:235–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement: Examining the Gateway Hypothesis. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kiros GE, Schaffran C, Hu MC. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:128–135. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi D. Peer effects on substance use among American teenagers. Journal of Population Economics. 2004;17(2):351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, MacLean A, Pebley A, Sastry N. Neighborhood and school effects on children’s development and well-being. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; Los Angeles, CA. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JB. The influence of parental separation on smoking initiation in adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43(1):56–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Princeton University and NBER. 2005 Retrieved October 6, 2005 ( http://www.nber.org/~kling/mto/mto_exp.pdf)

- Kumar R, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Effects of school-level norms on student substance use. Prevention Science. 2002;3(2):105–124. doi: 10.1023/a:1015431300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO. Norms relating to the desire for children. In: Bulatao RA, Lee RD, editors. Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries. Academic Press; New York: 1983. pp. 388–428. [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO. Multilevel analysis in the study of social institutions and demographic change. In: Huber J, editor. Macro-Micro Linkages in Sociology. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1991. pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdermott D. The relationship of parental drug use and parents’ attitude concerning adolescent drug use to adolescent drug use. Adolescence. 1984;19:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch B, Kandel DB. Drug use as a risk factor for premarital teen pregnancy and abortion in a national sample of young white women. Demography. 1992;29(3):409–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt RA. Policy interventions, low-level equilibria, and social interactions. In: Durlauf SN, Young HP, editors. Social Dynamics. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. National survey of American attitudes on substance abuse X: Teens and parents. Columbia University; 2005. Retrieved August 18, 2005 ( http://www.casacolumbia.org/Absolutenm/articlefiles/Teen_Survey_Report_2005.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Newman IM, Ward JM. The influence of parental attitude and behavior on early adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of School Health. 1989;59:150–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1989.tb04688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte AE, Smith BJ, O’Rourke T. The relative importance of parental attitudes and behavior upon youth smoking behavior. Journal of School Health. 1983;53(4):264–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1983.tb01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebley AR, Sastry N. Neighborhoods, poverty and children’s well-being. In: Neckerman KM, editor. Social Inequality. Russell Sage; New York: 2004. pp. 119–146. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins WH. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Supplement):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Haines MP, Rice R. Misperceiving the college drinking norm and related problems: A nationwide study of exposure to prevention information, perceived norms and student alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:470–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CE, Sastry N, Pebley AR, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Williamson S, Lara-Cinisomo S. RAND Working Paper DRU-2400/2-LAFANS. RAND Corporation; 2003. The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey: Codebook. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon RT., Jr . HLM 5: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations Across the Life Course. Aldine de Gruyter; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Family management and child development: Insights from social disorganization theory. In: McCord J, editor. Advances in Criminological Theory: Facts, Frameworks, and Forecasts, Vol. 3. Transaction. 1992. pp. 63–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. How do communities undergird or undermine human development? What are the relevant contexts and what mechanisms are at work? In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does it Take a Village? Community Effects on Children, Adolescents, and Families. Pennsylvania State University Press; University Park: 2001. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD. Ecological perspectives on the neighborhood context of urban poverty: Past and present. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol. 2: Policy Implications in Studying Neighborhoods. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F. Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:633–660. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105(3):603–651. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry N, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Adams J, Pebley AR. The design of a multilevel survey of children, families, and communities: The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Social Science Research. 2006;35(4):1000–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry N, Pebley AR. RAND Working Paper DRU-2400/7-LAFANS. RAND Corporation; 2003. Non-response in the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Retrieved March 19, 2004 ( http://www.rand.org/labor/DRU/DRU2400_7.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Sastry N, Pebley AR, Zonta M. RAND Working Paper DRU-2400/8-LAFANS. RAND Corporation; 2002. Neighborhood definitions and the spatial dimensions of daily life in Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Sen B. Does alcohol-use increase the risk of sexual intercourse among adolescents? Evidence from the NLSY97. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21:1085–93. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small ML, Newman K. Urban poverty after The Truly Disadvantaged: The rediscovery of the family, the neighborhood, and culture. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, Conard MW, Koetting O’Byrne K, Haddock CK, Poston WSC. Saturation of tobacco smoking models and risk of alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(3):190–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitler JO, Weiss CC. Effects of neighborhood and school environments on transitions to first sexual intercourse. Sociology of Education. 2000;73(2):112–132. [Google Scholar]