Abstract

A single GAG deletion in Exon 5 of the TOR1A gene is associated with a form of early-onset primary dystonia showing less than 40% penetrance. To provide a framework for cellular and systems study of DYT1 dystonia, we characterized the genetic, behavioral, morphological and neurochemical features of transgenic mice expressing either human wild-type torsinA (hWT) or mutant torsinA (hMT1 and hMT2) and their wild-type (WT) littermates. Relative to human brain, hMT1 mice showed robust neural expression of human torsinA transcript (3.90X). In comparison with WT littermates, hMT1 mice had prolonged traversal times on both square and round raised-beam tasks and more slips on the round raised-beam task. Although there were no effects of genotype on rotarod performance and rope climbing, hMT1 mice exhibited increased hind-base widths in comparison to WT and hWT mice. In contrast to several other mouse models of DYT1 dystonia, we were unable to identify either torsinA- and ubiquitin-positive cytoplasmic inclusion bodies or nuclear bleb formation in hMT1 mice. High-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection was used to determine cerebral cortical, striatal, and cerebellar levels of dopamine (DA), norepinephrine, epinephrine, serotonin, 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), homovanillic acid (HVA) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Although there were no differences in striatal DA levels between WT and hMT1 mice, DOPAC and HVA concentrations and DA turnover (DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA) were significantly higher in the mutants. Our findings in DYT1 transgenic mice are compatible with previous neuroimaging and postmortem neurochemical studies of human DYT1 dystonia. Increased striatal dopamine turnover in hMT1 mice suggests that the nigrostriatal pathway may be a site of functional neuropathology in DYT1 dystonia.

Keywords: dystonia, real-time RT-PCR, TOR1A, nigrostriatal, dopamine

Introduction

Dystonia is defined as a syndrome of involuntary muscle contractions, frequently causing twisting, repetitive movements and postures (Fahn, 1988). Dystonia is a common movement disorder, affecting over 300,000 people in the United States alone. Primary dystonia is a designation in which dystonia is the sole presenting disorder, without any underlying disease other than tremor in some cases (Fahn et al., 1998). Early-onset primary dystonia is characterized by twisting of the limbs, typically with onset in the distal leg, which may spread to involve writhing movements and fixed postures in other regions of the body. Symptoms usually appear in childhood; onset before 4 or after 28 years is uncommon (Bressman et al., 1998; 2000). Many cases of early-onset primary dystonia are associated with a GAG deletion in the TOR1A gene, which results in a single absent glutamic acid residue near the C-terminus of the encoded protein torsinA. DYT1 dystonia is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with less than 40% penetrance.

Postmortem neuropathological studies of brains from subjects with primary dystonia have failed to reveal any consistent evidence of neuronal loss, inflammation, or neurodegeneration. These finding suggest that functional and/or ultrastructural abnormalities, rather than neurodegenerative changes underlie dystonic symptoms (Rostasy et al., 2003). Recent morphological and biochemical studies have pointed to the dopaminergic system as a site of potential pathophysiological significance in human DYT1 dystonia. Rostasy and colleagues (2003) noted an increase in nigral cell density along with somatic enlargement of nigral dopaminergic neurons in humans with DYT1 dystonia. A significant increase in the turnover of dopamine, expressed as the ratio of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid to dopamine (DOPAC/DA), as well as a reduction in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor binding has also been reported in DYT1 dystonic striatum (Augood et al., 2002; Asanuma et al., 2005). These findings suggest an imbalance in dopaminergic neurotransmission and lend credence to the idea of a functional disturbance in patients with DYT1 dystonia. Interestingly, in situ hybridization and immunocytochemical studies have revealed high-level torsinA protein expression within dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta and cholinergic interneurons of the striatum (Konakova et al., 2001; Konakova & Pulst, 2001; Walker et al., 2001; Augood et al., 2003; Oberlin et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2004; Vasudevan et al., 2006). Furthermore, torsinA has been shown to protect dopaminergic neurons from oxidative stress (Kuner et al., 2004; Cao et al., 2005). These results, together with neurochemical findings in dystonic human brain, imply a supportive role for torsinA whereby a mutant and non-functional protein could lead to aberrant dopamine turnover/neurotransmission and the subsequent development of dystonia.

The above noted dopaminergic aberrations in human DYT1 dystonia are somewhat weakened by the limited number of DYT1 brains studied (Augood et al., 2002; Rostasy et al., 2003; Asanuma et al., 2005). Fortunately, animal models of DYT1 dystonia can be used to robustly interrogate findings in humans and open doors to novel avenues of study. In this regard, Sharma and colleagues (2005) have developed two lines of transgenic mice which harbor mutant (ΔGAG) transgenes (hMT1 and hMT2) along with mice which harbor the wild-type human TOR1A transgene (hWT). Transgenic mice which express mutant torsinA show reduced ability to learn motor skills in an accelerating rotarod paradigm at six months of age as well as abnormal dopaminergic D2 receptor responses in striatal cholinergic interneurons (Pisani et al. 2006). Furthermore, amphetamine induced dopamine release is attenuated in this model (Balcioglu et al., 2007). In the work described herein, we rigorously characterize the genetic, behavioral, morphological and neurochemical features of these transgenic models. Specifically, with species-specific primers and probes, quantitative real-time RT-PCR (QRT-PCR) was used to determine the relative expression levels of human and mouse torsinA transcripts in each transgenic line. Next, a comprehensive battery of behavorial tests was used to identify motor abnormalities. Electron and confocal microscopy were employed to evaluate previous reports of neuronal nuclear bleb formation and ubiquitin-positive cytoplasmic inclusions, respectively, in human DYT1 dystonia and other murine models of DYT1 dystonia (McNaught et al., 2004; Dang et al., 2005; Goodchild et al., 2005; Shashidharan et al., 2005; Grundmann et al., 2007). Finally, high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC-EC) was carried out to comprehensively quantify monoaminergic neurotransmitters and their metabolites in multiple neural structures.

Methods

All experiments were approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled environment with free access to food and water. Light was controlled on a 12 hr light/dark cycle; lights on at 6:00 am.

DYT1 transgenic mouse model and genotyping

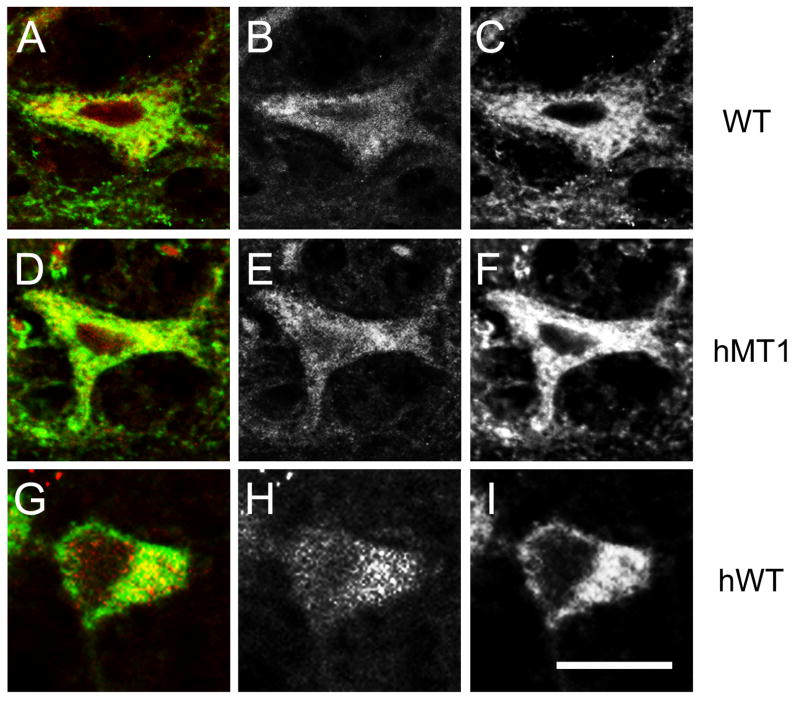

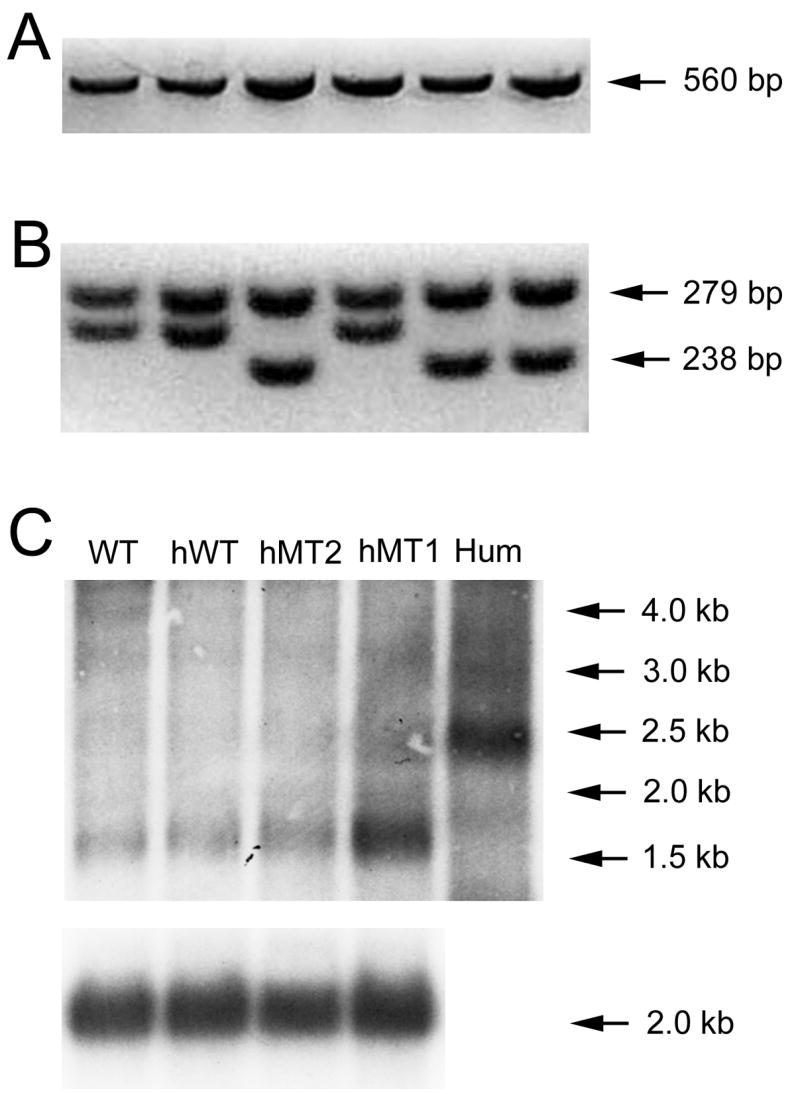

Breeding colonies of human wild-type (hWT) and mutant torsinA (hMT1 and hMT2) mice were established at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC) by matings with wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice. All mice used in experiments were C57BL/6 backcrossed at least 8X. Tail DNA from the breeders and their offspring were isolated using the AquaPure Genomic DNA Tissue Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) for genotyping. Two primers, 5′-CACATTGCACTTTCCACATGCT -3′ and 5′-GTTTTGCAGCCTTTATCTGA-3′, amplified a 560 bp segment (35 cycles; annealing temperature − 60°C) within the human torsinA coding sequence that was identified via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1A). The genotype of the breeders was confirmed by restriction digestion with BseRI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The human WT torsinA PCR product was digested with BseRI into four fragments (279 bp, 238 bp, 24 bp, and 22 bp). The human mutant torsinA PCR product was digested with BseRI into three fragments (279 bp, 259 bp, and 22 bp); fragment profiles were then identified with 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Genotyping and Northern blot analysis of hWT, hMT1, and hMT2 transgenic mice. Gel images of PCR products before (A) and after (B) digestion are shown. Products from hMT1 or hMT2 mice appear in lanes 1, 2 and 4 while products from hWT mice appear in lanes 3, 5 and 6. (C) Northern blot for human torsinA in WT, hWT, hMT1, and hMT2 mice. Mouse β-actin loading controls appear below each lane. Hum, human mRNA.

Northern blot hybridization

Whole brain RNA from WT (n = 4), hWT (n = 4), hMT1 (n = 3), and hMT2 (n = 4) mice was extracted with TRI reagent® (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and DNA was removed with DNA-free™ (Ambion). Total RNA quality was examined with agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Pooled human whole brain RNA was obtained from Ambion (Human Brain Reference RNA, n = 23 brains). The MicroPoly(A)Purist kit from Ambion was used to extract mRNA from total RNA. The mRNA was electrophoretically resolved on denaturing gels and transferred to positively charged nylon membranes. Radiolabeled (32P-UTP) complementary RNA (cRNA) probes were generated by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase. After ultraviolet crosslinking, blots were prehybridized and then hybridized overnight with both TOR1A and Actb (β-actin) cRNA probes. The TOR1A probe was generated from human cDNA template, whereas the Actb probe was generated from mouse cDNA template. After washing, blots were exposed to Kodak Biomax MR radiographic film prior to development.

QRT-PCR

RNA was extracted with TRI reagent® (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and DNA removed with DNA-free™ (Ambion). Total RNA quality was examined with agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with Ambion’s RETROscript™ kit using 500 ηg total RNA as template. The reaction mixture was incubated at 44 °C for 1 hr and then at 92 °C for 10 min. QRT-PCR was performed using the Roche LightCycler 480 with gene specific primers and Universal Taqman® probes (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for both the target genes (human torsinA and mouse torsinA) and endogenous control (Cyclophilin D). A primer pair (5′-GCGTCTCTACTGCCTCTTCG -3′ and 5′-GGTTGTCGTCCAGATCCTTC -3′) and probe (5′-GGGCAGAAG -3′) were used to specifically detect the human torsinA sequence. In similar fashion, a primer pair (5′-CCGTGTCGGTCTTCAATAACA -3′ and 5′-AATAATCTATGAGGTTCCGGTCAA-3′) and probe (5′-CAGCAGCC -3′) were used to specifically detect the mouse torsinA sequence. Relative levels of human torsinA transcript in mouse brain were calculated relative to Human Brain Reference RNA and total RNA from normal human striatum (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA; n = 1 brain) whereas levels of mouse whole brain (hWT [n = 4], hMT1 [n = 3], and hMT2 [n = 4]) and striatal (hWT [n = 6], hMT1 [n = 8], and hMT2 [n = 4]) torsinA mRNA in mice were calculated relative to WT littermates (whole brain [n = 4] and striatum [n = 6]).

Behavioral assessment

Adult (3–4 month) male hWT (n = 24) and hMT1 (n = 35) mice, along with WT (n = 20) age-and gender-matched littermate controls were used for quantitative analyses of motor function (Jiao et al., 2005). In addition, hMT1, hMT2, and hWT mice, including animals over one year of age, were routinely observed for evidence of dystonia during open field behavior.

Rotarod performance

Mice were acclimated to a Rotamex-5 rotarod (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) rotating at 5 rpm for 5 min one day prior data acquisition. Two motor assessments were then performed. The first assessment began with a 30 s acclimation period at 4 rpm followed by an acceleration of 4 rpm every 30 s to a maximum of 5 min at 40 rpm. Mice were given three trials at the same time each day for 5 consecutive days. The second assessment began with an initial speed of 4 rpm, gradually accelerating at a rate of 1 rpm every 5 s to an incremented target speed for 5 consecutive days (5, 10, 20, 30 and 40 rpm, respectively). Transgenic and WT littermate mice were randomly selected for one of these two trials. All tests were performed in technical triplicate and median values were used for statistical comparison.

Footprint analysis

Mouse forepaws (green) and hindpaws (red) were dipped in nontoxic water-based paints. Mice were then allowed to walk down an enclosed runway lined with white paper. Three trials were performed on three separate days within one week. Two to four steps from the middle portion of each run were measured for (1) stride length, (2) hind-base width (the distance between the right and left hindlimb strides) and (3) front-base width (the distance between the right and left forelimb strides). At least seven steps were measured for each mouse. Mean values were used for statistical analysis.

Tail suspension

This test involved the response of each mouse to 1 min of vertical suspension from the tail. Neurological dysfunction is exhibited as hindlimb and/or forelimb clasping during this maneuver.

Vertical rope climb

Mice were acclimated to a vertical, 40-cm long, 10-mm thick nylon rope prior to testing. The bottom of the rope was suspended 15 cm above a padded base and the top entered into a darkened escape box. Three trials with a 5-min intertrial interval were completed for each mouse. Median times were used for statistical analysis.

Raised-beam task

Mice were acclimated to an 80-cm long, 20-mm wide beam elevated 50 cm above a padded base. A 60W lamp at the start served as an aversive stimulus, whereas the opposite end of the beam entered a darkened escape box. Transversal time and number of slips were measured as mice traversed the beam. After initial testing with a 20-mm diameter square beam, mice were given follow-up tests using supplementary round (8-mm and 12-mm diameter) and square (12-mm diameter) beams. All testing was performed in triplicate and median values were used for subsequent statistical analyses.

Confocal microscopy

Adult (3–4 month) male WT (n = 3), hWT (n = 3) and hMT1 (n = 3) mice were overdosed with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally [IP]) prior to transcardiac perfusion with heparinized saline and then 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Brains were dissected and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for another 2 hrs and then incubated in a cryoprotectant solution (30% sucrose/0.1 M PB, pH 7.4) for at least 48 hrs. Brains were sectioned at 20 μm on a cryostat, collected onto SuperFrost®-Plus glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), circled with a PAP pen (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA) and allowed to dry on a slide warmer for 10 min. Sections were blocked in 2% nonfat dry milk and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.02 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal anti-torsinA antibody D-M2A8 (1:300 diluted in PBS with 3% normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100) and rabbit polyclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody (1:1000, Dakocytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Sections were then incubated for 4 hr with biotinylated horse anti-mouse (1:500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and rhodamine red-X (RRX)- tagged donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) diluted in PBS with 2% normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. After rinsing with PBS, sections were incubated for 1 hr with Cy2-tagged streptavidin (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) diluted in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100. Sections were rinsed, air-dried, dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped with 1,3 diethyl-8-phenylxanthine mounting compound (DPX; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Sections were visualized with both epifluorescence (Leica DM6000, Leica Microsystems Inc, Bannockburn, IL, USA) and confocal laser-scanning (Bio-Rad) microscopy.

Electron microscopy

Adult (3–4 month) male WT (n = 3), hWT (n = 3), and hMT1 (n = 3) mice were overdosed with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, IP) prior to transcardiac perfusion with heparinized saline and then 4% paraformaldehyde/2.5% glutaraldehyde/15% picric acid in 0.1 M PB. The brains and cervical spinal cords were dissected from surrounding tissue. Regions of interest (striatum, pons, cerebellar cortex, and spinal cord) were cut into 3 × 3 × 3 mm blocks and post-fixed overnight. Next, tissue blocks were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) in PBS for 4 hrs and rinsed briefly in deionized water. After ascending dehydration in 30%, 50%, 70%, 85%, 95%, and 3 X 100% ethanol (each for 30 min), tissue blocks were then infiltrated with 50% Spurr (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 100% ethanol overnight at room temperature, then 100% Spurr over 8 hrs. Blocks were cured at 70 °C for 2 days. One micrometer sections were cut on a Reichert Ultracut E microtome (Reichert Instruments, Depew, NY, USA) and stained with toluidine blue. Areas of interest were selected, sectioned at 75 ηm, mounted onto 150 mesh grids, post stained with 4% uranyl acetate in methanol and Venable lead citrate. Sections were visualized and photographed with a JEOL 2000EX transmission electron microscope (JOEL USA Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) at 60 kV with 30,000X magnification.

HPLC-EC analysis of monoamines and their metabolites

All standards, including 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), serotonin hydrochloride (5-HT), dopamine hydrochloride (DA), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), epinephrine hydrochloride (EPI), homovanillic acid (HVA), norepinephrine hydrochloride (NE), and 4-hydroxy-3-methoxymandelic acid (VMA) were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium octylsulphonate (SOS) and monobasic anhydrous sodium dihydrogen phosphate used in mobile phase preparation were purchased from Fluka Chemie (Buchs, Switzerland). HPLC grade water and acetonitrile were obtained from Fisher Scientific.

Tissues from adult (3–4 month) male hWT (n = 10) and hMT1 (n = 11) mice, along with WT (n = 10) age- and gender-matched littermate controls were analyzed using HPLC-EC to quantify cerebral cortical, striatal and cerebellar levels of DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, DOPAC, HVA, and 5-HIAA.

Fresh samples of striatum, cerebellar cortex, and cerebral cortex were weighed and then homogenized in 100 μl of an ice-cold solution of 0.1 M perchloric acid, 0.1 mM sodium metabisulfite and 0.1 mM EDTA per 10 mg wet weight. Homogenates were then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 25 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were filtered through 0.22 μm pore size polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) syringe-driven membrane filters (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA) and immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C until the time of analysis.

HPLC analysis was performed with an ESA Model 5600A CoulArray® system (ESA Inc., Chemlsford, MA, USA), equipped with Shimadzu Model DGU-14A on-line degassing unit (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA), an ESA Model 582 pump, and an ESA Model 542 refrigerated autosampler. The detection system consisted of three coulometric array modules, each containing four electrochemical detector cells. Electrode potentials were selected over the range of +50 to +600 mV, with a 50 mV increment against palladium electrodes. Chromatographic separation was achieved by auto-injecting 20 μl sample aliquots at 5 °C onto a MetaChem Intersil (MetaChem Technologies, Torrance, CA, USA) reversed-phase C18 column (5 μm particle size, 250 × 4.6 mm I.D.) with an ESA Hypersil C18 guard column (5 μm particle size, 7.5 × 4.6 mm I.D.). The mobile phase used for compound separation consisted of 75 mM monobasic sodium dihydrogen phosphate, 2.0 mM SOS, 25 μM EDTA, and 100 μl of triethylamine and 10% acetonitrile, pH 3.0. A flow rate of 1.5 ml/min and analysis time of 45 min was used for all experiments. System control and data acquisition/processing were performed using ESA CoulArray software (version 1.02). All samples were processed in technical triplicate and median values used for statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses

The results of all locomotor and biochemical experiments were analyzed by means of a one-way analysis of variance using SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Post-hoc comparisons were based on the a priori hypothesis that hMT1 mice would differ from WT littermates. An alpha (α) of 0.05 was chosen for statistical significance.

Results

TorsinA expression in the transgenic mice

The transgenic expression of human torsinA was confirmed with Northern blot analyses. As shown in Fig. 1C, human torsinA transcript appears as a 1.5 kb band in transgenic mice and a 2.5 kb fragment in human brain. The expression of human torsinA was robust in hMT1 mice but weak in hWT and hMT2 mice.

To extend the Northern blot results, QRT-PCR was performed with total RNA from both whole brain and striatum, along with species-specific primers and probes. Cyclophilin D was used as an endogenous control. The amplification efficiencies of human torsinA (1.99), mouse torsinA (1.98), human cyclophilin D (1.98) and mouse cyclophilin D (1.97) were nearly identical.

The whole brain expression of human torsinA was measured in all three transgenic lines relative to pooled human whole brain reference RNA whereas expression of human torsinA in the mouse striatum was referenced to RNA obtained from a single human striatum. As shown in Table 1, hMT1 mice showed robust whole-brain and striatal expression of human torsinA transcript (3.90X or 390% in the whole brain and 4.95X or 495% in striatum). In contrast, hWT and hMT2 mice expressed relatively low levels of human torsinA transcript. Due to the high level of human mutant torsinA expression in hMT1 transgenic mice and the low level of mutant torsinA expression in hMT2 mice, behavioral, morphological, and neurochemical studies were limited to the hMT1 transgenic line.

Table 1.

Relative levels of human and mouse torsinA transcripts in transgenic mice and wild-type littermates

| Whole Brain RNA | Striatal RNA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line | Human torsinA transcript* | Mouse torsinA transcript | Human torsinA transcript** | Mouse torsinA transcript |

| hMT1 | 3.90 ± 0.451 | 1.14 ± 0.14 | 4.95 ± 0.34 | 1.33 ± 0.22 |

| hMT2 | 0.07 ± 0.002 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 1.04 ± 0.06 |

| hWT | 0.04 ± 0.001 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.90 ± 0.05 |

| WT littermates | -- | 1.01 ± 0.02 | -- | 1.07 ± 0.04 |

Relative to pooled RNA from 23 human brains.

Relative to striatal RNA from a single human brain.

The relative expression of endogenous mouse torsinA transcript was calculated for the three transgenic lines. Analysis of Table 1 indicates that the directions of change in relative expression were the same for whole brain and striatum. In whole brain, there were neither overall nor individual effects of genotype on relative levels of mouse torsinA transcript. In striatum, although the effect of genotype on endogenous torsinA expression was not significant (F3, 27 = 2.09, p < 0.130), individual comparisons revealed a significant difference between endogenous torsinA expression in hWT and hMT1 mice (F1, 27 = 6.21, p < 0.05).

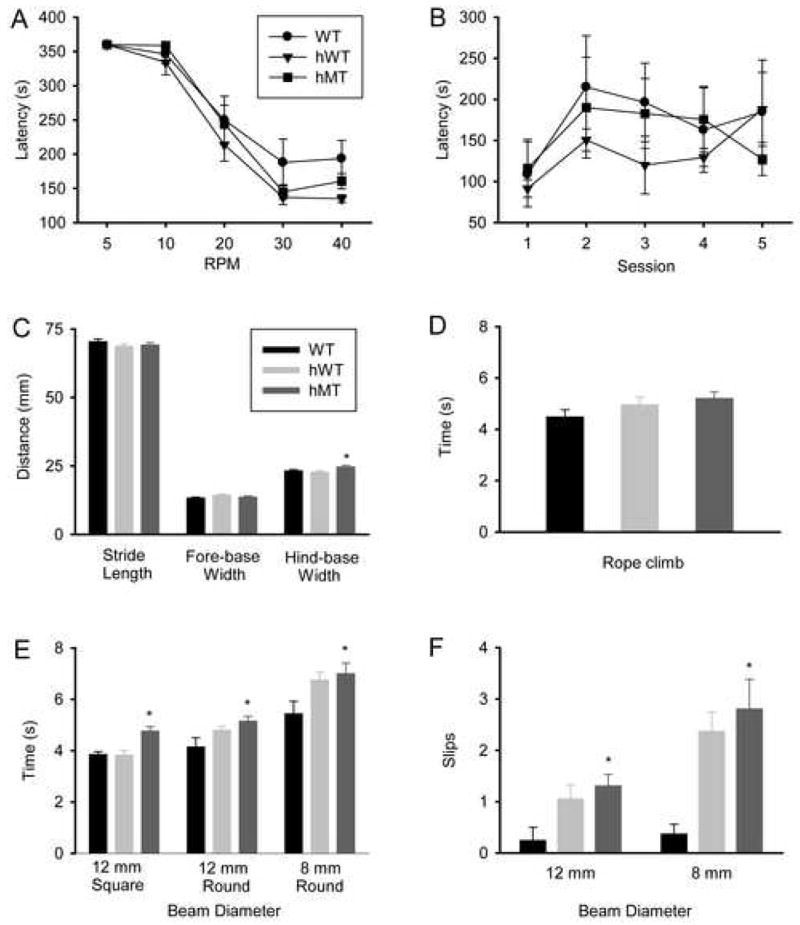

Motor dysfunction in DYT1 transgenic mice

The motoric abilities of transgenic mice were evaluated using a battery of tests including the raised-beam task, vertical rope climbing, footprint analysis, and an accelerating rotarod. In addition, we examined the response of transgenic mice to tail suspension. In aggregate, these tests assess several overlapping aspects of sensorimotor function such as motor power, coordination, and postural stability.

There was no clear-cut evidence of dystonia in any of the mice. There were no effects of genotype on either the accelerating rotarod (Fig. 2A and B) or vertical rope climbing (Fig. 2C). However, there were significant effects of genotype on footprint analysis and the raised-beam task (p < 0.05, for both). Compared to WT littermates, hMT1 mice showed increased hind-base width on footprint analysis (F1, 76 = 5.21, p < 0.025, Fig. 2C) and prolonged traversal times on the 12-mm square raised-beam task (F1, 53 = 18.85, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2E). WT, hWT, and hMT1 mice did not differ in their response to tail suspension. In particular, no mice exhibited forepaw or hindpaw clasping within the 1-min period of observation.

Figure 2.

Behavioral analysis of motor functioning in DYT1 transgenic mice. Performance of WT (filled circles or black bars), hWT (filled inverted triangles or gray bars) and hMT1 (filled squares or dark gray bars) mice in an accelerating rotarod with increasing destination speeds (A); in an accelerating rotarod with the same destination speed for five consecutive days (B); in footprint analysis (C); vertical rope climbing (D); and the raised beam task with 12-mm square-beam, 12-mm round-beam, and 8-mm round-beam (E, F). * denotes a significant difference between hMT1 and WT littermates (p < 0.05).

In follow-up raised beam task experiments, the effect of genotype on 12-mm and 8-mm round-beam tasks was significant for both traversal times (F2, 37 = 5.62, p < 0.007; and F2, 37 = 3.52, p < 0.040; respectively) and slip counts (F2, 37 = 3.55, p < 0.039; and F2, 37 = 5.45, p < 0.008; respectively). Compared to WT mice, hMT1 mice demonstrated a 24% increase in traversal times and a 425% increase in slip counts on the 12-mm round-beam task (p < 0.05, for both). As shown in Figs. 2D and 2E, a 29% increase in traversal times along with a 650% increase in slip counts were noted on the 8-mm round-beam task (p < 0.05, for both). The hWT mice also exhibited prolonged traversal times and more frequent slips on the round-beam tasks (p < 0.05, for all).

Morphological phenotype of DYT1 transgenic mice

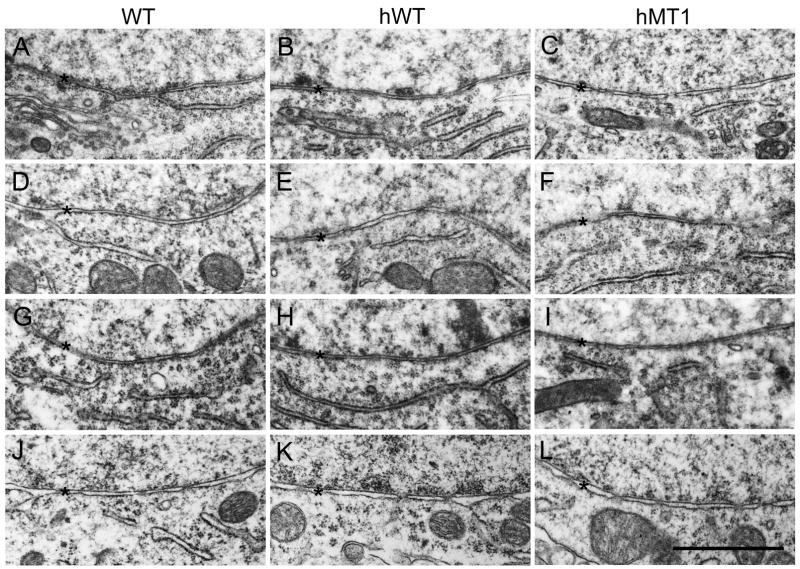

Fluorescent immunocytochemistry was performed to search for ubiquitin- and/or torsinA-positive cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in hMT1 mice. Although all brain regions were surveyed, particular attention was focused on the pontine nuclei, cerebral cortex, striatum, substantia nigra pars compacta and midbrain. The relative distribution of torsinA- and ubiquitin-immunoreactivity (IR) did not differ between hMT1 and WT mice (Fig. 3). TorsinA- and ubiquitin-IR were localized to the cytoplasm of neurons but did not co-localize to cytoplasmic inclusions. The subcellular localization pattern of torsinA-IR in hMT1 mice was similar to WT littermates with no evidence of increased torsinA-IR surrounding the nuclear envelope. Electron microscopy was used to search for ultrastructural abnormalities of the nuclear envelope. In contrast to several other mouse models of DYT1 dystonia, we were unable to identify bleb formation at the nuclear envelope in hMT1 mice (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Double-label immunocytoochemistry for torsinA and ubiquitin in hMT1, hWT and WT mice. Examples of torsinA-IR (green) and ubiquitin-IR (red) are shown from the pontine nuclei. Gray scale images of ubiquitin-IR (B, E, and H) and torsinA-IR (C, F, and I) are shown for comparison with merged images (A, C, and G). A–C, WT. D–F, hMT1. G–I, hWT. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Figure 4.

Electron microscopic images of the nuclear envelope in the pontine nuclei (A–C), cerebellum (D–F), spinal cord (G–I), and striatum (J–L). A, D, G, and J are sections taken from WT mice. B, E, H, and K are sections taken from hWT mice. C, F, I, and L are sections taken from hMT1 mice. * denotes the nuclear envelope.

Neurochemical phenotype of DYT1 transgenic mice

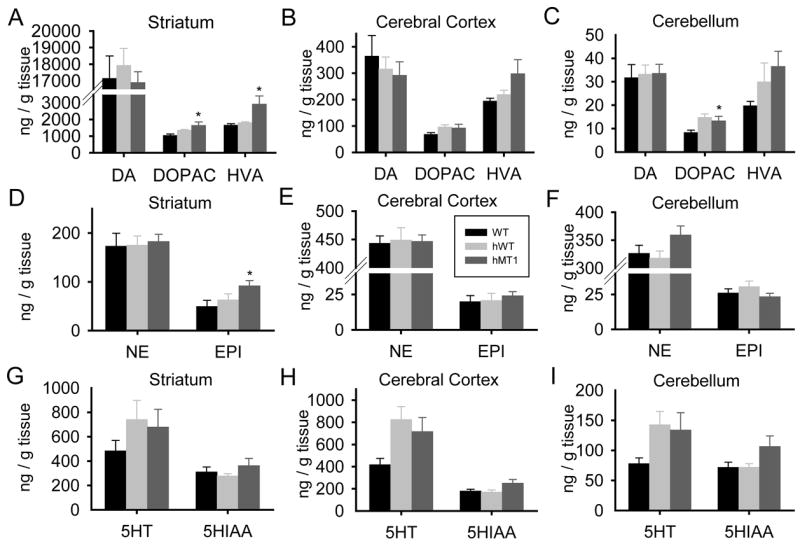

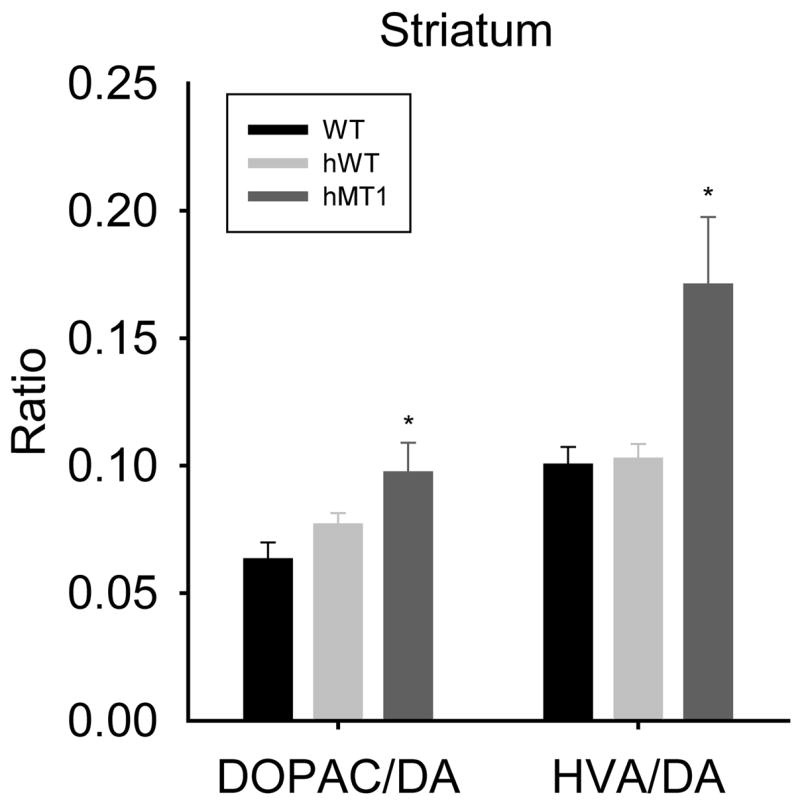

In order to examine the possibility of a neurochemical imbalance in ΔGAG DYT1 transgenic mice, HPLC-EC was performed to quantify levels of monoamines and their metabolites in striatum, cerebellum and cerebral cortex. As seen in Fig. 5C, there was a noteworthy effect of genotype on the level of DOPAC (F2, 28 = 4.89, p < 0.015) in the cerebellum. Compared to WT mice, DOPAC was 59% higher (p < 0.026) in hMT1 mice. In cerebral cortex, a significant effect of genotype was apparent with respect to 5-HT (F2, 28 = 3.87, p < 0.033; Fig. 5H). Compared to WT littermates, 5-HT content was 98% higher (p < 0.012) in hWT mice. Similarly, 5-HT content also tended to be higher in hMT1 than in WT mice (76%, p < 0.054). In the striatum, significant effects of genotype were observed for EPI (F2, 28 = 3.45, p < 0.046), DOPAC (F2, 28 = 4.99, p < 0.014) and HVA (F2, 28 = 5.26, p < 0.012) levels (Fig. 5A and D). In comparison to WT mice, EPI, DOPAC and HVA levels were increased by 85% (p < 0.016), 58% (p < 0.004) and 76% (p < 0.007), respectively, in hMT1 mice. Although there was no significant difference in striatal DA content between hMT1 and WT mice, DA turnover (DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA) was significantly higher in the mutants (p < 0.006 or both; Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Quantitative HPLC-EC analysis of DA and its metabolites DOPAC and HVA (A-C); NE and EPI (D–F); and 5-HT and its metabolite 5-HIAA (G–I) in striatum, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum of WT (black bars), hWT (gray bars), and hMT1 (dark gray bars) mice. * denotes a significant difference between hMT1 and WT littermates (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Dopamine turnover in the striatum of WT (black bars), hWT (gray bars), and hMT1 (dark gray bars) mice as indicated by DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA ratios. * denotes a significant difference between hMT1 and WT littermates (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Several murine models of DYT1 dystonia have been developed and characterized to varying degrees (Dang et al., 2005, Goodchild et al., 2005; Sharma et al., 2005; Shashidharan et al., 2005; Dang et al., 2006; Grundmann et al., 2007; Table 2). While some common themes exist among these models, substantial discordance has been apparent in morphological findings and robust behavioral and neurochemical characterizations have been largely incomplete. In our study, detailed genetic, behavioral, morphological and neurochemical analyses were performed in a human ΔGAG transgenic mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. Our results demonstrate high-level mutant transgene expression in hMT1 mice, in addition to distinct motor and neurochemical abnormalities in the hMT1 line. These findings demonstrate that the human mutant torsinA transgenic mouse (hMT1) is a valid model for the study of DYT1 dystonia. Of utmost importance, our results indicate that increased striatal dopamine turnover may be critical to the pathobiology of DYT1 dystonia.

Table 2.

Murine DYT1 models

| Model | Molecular Construct | Morphology | Behavior | Neurochemistry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DYT1 transgenic (Shashidharan et al., 2005) | 7.1 kb fragment from the pNSE-Ex4 vector containing the neuronspecific enolase promoter, human mutant (ΔGAG) torsinA-cDNA and SV40 polyA signal | ubiquitin- and torsinA-IR perinuclear aggregates and/or inclusion in the pedunculopontine nucleus, pons & periaqueductal gray | 40% of transgenic mice from each line displayed dystonic movements of the limbs with self-clasping, circling behavior, & hyperactivity | ↓ striatal DA in transgenic animals that exhibited an abnormal behavioral phenotype, ↓ striatal DOPAC/DA ratio in all transgenic mice |

| DYT1 transgenic (Sharma et al., 2005) | human wildtype (hWT) or mutant (ΔGAG) torsinA-cDNAs were inserted into pcDNA3.1 under the human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter. | no torsinA-positive inclusions or increased staining around the nuclear envelope (NE) | reduced ability to learn motor skills in an accelerating rotarod paradigm | ↓ amphetamine-induced striatal extracellular DA levels |

| DYT1 knock-in (Dang et al., 2005) | Exon 5 in the targeting vector construct carries a GAA deletion at codon 302. The PGKNeoSTOP cassette with a false translation signal, splice donor site, and an additional poly(A) tail was inserted into intron 4. | ubiquitin- and torsinA- containing aggregates in pontine nuclei of male DTY1 knock-in mice | deficient performance on the beam-walking test, open-field hyperactivity | ↓ striatal HVA |

| DYT1 knock-out (Goodchild et al., 2005) | Exons 2-4 of Tor1a were replaced by a cassette containing Neo and IRES-tau LacZ sequences | vesicles within the neuronal NE that appear to derive from the inner nuclear membrane | ||

| DYT1 knock-in (Goodchild et al., 2005) | Exon 5 in the targeting construct carries a GAG deletion. Neo cassettewas inserted into intron 4 of Tor1a. | homozygotes exhibit vesicles within the neuronal NE that appear to derive from the inner nuclear membrane | ||

| TOR1A knock-down (Dang et al., 2006) | PGKNeoSTOP cassette with a false translation signal, splice donor site, and an additional poly(A) tail was inserted into intron 4 of Tor1a and recombination occurred 5′ to an Exon 5 GAA deletion | horizontal hyperactivity, ↑ slips on a beam-walking test | ↓ striatal DOPAC | |

| DYT1 transgenic (Grundmann et al., 2007) | human wild-type (hWT) and mutant (hΔGAG) torsinA-cDNAs were inserted into pBluescript II SK-vector under the 3.4 kb fragment of the murine prion protein promoter and tagged C-terminally with V5-His | inclusion-like formation in brainstem nuclei, torsinA-IR localized to the NE, and NE abnormalities in both hWT and hΔGAG mice | hWT mice: hypoactivity, short stride length, prolonged traversal times on beam walking

hΔGAG mice: hyperactive, defects on rotarod testing |

hWT mice: ↓ striatal DA, 5-HT and 5-HIAA; ↓ brainstem HVA

hΔGAG mice: ↑ brainstem DOPAC, 5-HT and 5-HIAA |

Transgenic models of DYT1 dystonia have been developed by Sharma et al. (2005), Shashidharan et al. (2005), and Grundmann et al. (2007). Using quantitative analysis of Western blots, Sharma and colleagues (2005) showed that hMT1, hMT2, and hWT transgenic mice express torsinA at 2.1X, 1.3X, and 2.3X that of WT littermates. Similarly, Shashidharan and coworkers (2005) showed increased torsinA protein expression in four transgenic lines (TG#13, TG#22, TG#35, and TG#49). In more recent work, Grundmann and colleagues (2007) analyzed normal and mutant human torsinA transgene expression at both the transcript and protein levels. Human torsinA transcript levels were referenced to the hWT24 line of mice. The largest fold increase in transcript levels was noted in the hΔGAG3 line of torsinA mutant mice (1.30X). In a more functional assay, we showed that striatal torsinA transcript expression was 3.90X higher in hMT1 mice than in human brain. Since current thinking indicates that a single mutant torsinA molecule can disrupt assembly of a mature hexameric molecular motor (Breakefield et al. 2001), stoichiometric considerations would suggest that an increase in the cellular burden of mutant torsinA would decrease the probability of hexamer formation. Apparently, a minimal number of functional torsinA hexamers are required for normal neural function and organismal survival since DYT1 knockout and homozygous DYT1 knock-in mice die shortly after birth (Goodchild et al. 2005). Therefore, robust transgenic expression of mutant torsinA as seen in hMT1 mice may be the most viable means of modeling human DYT1 dystonia.

Genetically engineered mice cannot accurately model all of the molecular, cellular, and physiological features of human neurogenetic disorders. Individual models have their own distinct limitations and utilities. In transgenic models, the promoter, construct design, and insertion site dictate the temporal and spatial regulation of transgene expression. Moreover, transgenic models may be associated with locus-specific insertional effects. In comparative analysis of torsinA transgenic models, several points must be considered. First, utilization of a neuron-specific promoter like neuron-specific enolase precludes consideration of glial-specific and glial-neuronal interactions as contributors to the pathophysiology of DYT1 dystonia (Shashidharan et al., 2005). Furthermore, the mice generated by Shashidharan and colleagues (2005) exhibit bizarre circling behavior that is not seen in other murine models of DYT1 dystonia. In the transgenic mice generated by Grundmann et al. (2007), the expression of mutant torsinA containing a V5-his tag is driven by the murine prion protein promoter (Grundmann et al., 2007). It is possible that even a small V5-his tag could interfere with one or more functional properties of torsinA. In contrast to other transgenic models of DYT1 dystonia, expression of untagged mutant torsinA in hMT1 mice is driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, well known for its ability to drive widespread transgene expression (Boshart et al., 1985; Sharma et al., 2005).

Similar to other models of DYT1 dystonia, none of the transgenic mice used in our study (hMT1, hMT2, and hWT) showed overt evidence of dystonia. The response of hMT1 mice to tail suspension and performance on vertical rope climbing and the accelerating rotarod were all similar to WT littermates. However, hMT1 mice exhibited a mildly abnormal motor phenotype characterized by increased hind-base width and impaired performance on the raised-beam task. These findings are consistent with previous reports in heterozygous DYT1 knock-in and DYT1 knock-down mice (Dang et al., 2005; 2006), as well as hWT24 transgenic mice (Grundmann et al., 2007). DYT1 knock-in mice display an abnormal gait with significant overlap in paw placement, as well as motor coordination deficits on the raised-beam task (Dang et al., 2005). DYT1 knock-down mice demonstrate motor coordination deficits on the raised-beam task as well (Dang et al., 2006). The raised beam task integrates multiple components of the sensorimotor system and has been used for functional evaluation of the nigrostriatal pathway (Dluzen et al., 2001) and to estimate the deficits induced by sensorimotor cortex ablation (Goldstein & Davis, 1990) and ischemic stroke (Brown et al., 2004). The raised-beam task has also been used to characterize motor dysfunction in murine models of “basal ganglia” disorders such as Huntington and Parkinson diseases (Carter et al., 1999; Strome et al., 2006). Since abnormalities in dopaminergic neurotransmission in mice have been associated with hypoactivity, stride-length reduction and poor performance on the raised-beam task, an explanation for the motor abnormalities of hMT1 transgenic mice may be derived, in part, from the observed increase in striatal DA turnover (Dluzen et al. 2001; Fernagut et al. 2002; 2003).

Footprint analysis is another useful tool used to evaluate motor and gait abnormalities in murine models of movement disorders. Footprint analysis along with digital surrogates have been used to examine gait alterations induced by striatal damage (Teunissen et al., 2001), genetic defects of Purkinje cells (Jiao et al., 2005), sensory neuropathy (Wietholter et al., 1990) and diffuse cerebral disease (McGavern et al., 1999). As is the case for human gait disorders, distinct footprint patterns can be ascribed to lesions of specific neural subsystems in mice. Animals with cerebellar defects, for instance, oftentimes display considerable increases in both front- and hind-base widths (Wietholter et al., 1990; Jiao et al., 2005). In agreement with functional imaging studies, the increased hind-base width noted in hMT1 mice suggests that mutant torsinA may contribute to cerebellar dysfunction in humans with DYT1 dystonia (Carbon et al., 2004).

Work in Drosophila suggests that torsinA could play a role at the mammalian neuromuscular junction (Koh et al., 2004). In our study, the performance of torsinA mutant mice on vertical rope climbing does not entirely dismiss this possibility since hMT1 mice tended to perform worse than WT littermates. Vertical rope climbing requires substantial motor strength and is likely to illicit abnormalities in mice with disorders of muscle, the neuromuscular junction, or anterior horn cells (Anderson et al., 2005).

Unlike two previous studies with torsinA transgenic mice, we were unable to identify rotarod abnormalities in either hMT1 or hWT mice (see Table 2). In this regard, several points are worthy of note. First, Grundmann et al. (2007) employed 6-month old mice and Sharma and colleagues (2005) only found rotarod abnormalities in mice at 9 months of age. In contrast, our studies were performed in much younger adult mice. Second, Sharma et al. (2005) pooled results from hMT1 and hMT2 mice whereas we restricted our behavioral experiments to hMT1 mice. Finally, all of our experiments were performed with mice backcrossed (C57BL/6) at least 8 generations, whereas Sharma et al. (2005) combined F5 and F6 progeny for their experiments. Grundmann et al. (2007) did not comment on the genetic uniformity of their mice. In this context, it should be emphasized that our hWT mice are not a viable model of human wild-type torsinA overexpression. Similarly, with regards to the hMT2 mice, it is likely that mutant transgene expression is too low to signficantly disrupt cellular pathways dependent on torsinA. It is possible that transgene repression or inactivation, which has been described in numerous plant and animal models is responsible for the Northern blot and QRT-PCR results seen in hWT and hMT2 mice (Kilby et al., 1992; Chevalier-Mariette et al., 2003; Thomas et al. 2005). DNA methylation, which may occur over several generations, appears to be the most common mechanism of transgene repression/inactivation.

Laser-scanning confocal and electron microscopy were used to search for cellular and ultrastructural abnormalities in torsinA transgenic mice. Our results are compatible with the initial report of Sharma and colleagues (2005), but differ from findings in other DYT1 transgenic, knock-in and knock-out models. (Shashidharan et al., 2004; Dang et al., 2005; Goodchild et al., 2005; Grundmann et al., 2007). Morphological analysis of other DYT1 models has revealed ubiquitin- and torsinA-positive cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Shashidharan et al., 2004; Dang et al., 2005; Grundmann et al., 2007), as well as bleb formation at the nuclear envelope (Goodchild et al., 2005; Grundmann et al., 2007; Table 2). It is likely that technical factors related to tissue processing, rodent age and relative cytoplasmic concentration of endogenous torsinA contribute to the appearance of cytoplasmic inclusions and nuclear envelope bleb formation. Since DYT1 dystonia rarely appears after 28 years of age, we chose to use young adult mice for our studies. Since inclusion formation in most neurodegenerative diseases is closely tied to the aging process, our failure to detect cytoplasmic inclusions in young adult mice is not surprising. With regard to nuclear envelope bleb formation, it should be emphasized that our mice were perfused with a fixative (4% paraformaldehyde/2.5% glutaraldehyde/15% picric acid) well-known to preserve ultrastructural morphology. Marked reduction in functional torsinA is also required for the appearance of nuclear envelope blebs since structural abnormalities of the nuclear envelope were described in homozygous DYT1 knock-in and knock-out mice, but not in their heterozygote DYT1 littermates (Goodchild et al., 2005). In aggregate, motor and neurochemical abnormalities are observed in DYT1 models that demonstrate cellular pathology, as well as in those that do not. Thus, causal relationships among morphological, motor, and neurochemical phenotypes remain unclear.

To investigate the possibility of a neurochemical abnormality in torsinA mutant mice, we performed HPLC-EC analysis of monoamine transmitters and their metabolites. The most striking findings were significantly increased DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA ratios (measures of DA turnover) in hMT1 striatum. Increases in DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA turnover can manifest from a number of scenarios including increased DA release, decreased DA uptake due to abnormal functioning of the dopamine and/or vesicular monoamine transporters or increased monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity. Our findings in DYT1 transgenic mice are compatible with previous neuroimaging and postmortem neurochemical studies of human DYT1 dystonia. For example, Augood and colleagues (2002) observed a significantly increased DOPAC/DA ratio, along with a trend toward reduction in D1 and D2 receptor binding in the striatum of human postmortem DYT1 dystonia brains. A corresponding decrease in striatal D2 receptor binding has been described in non-manifesting DYT1 mutation carriers (Asanuma et al., 2005). Increased striatal DA turnover and down-regulation of striatal D2 receptors suggests that functional and/or morphological anomalies of the nigrostriatal pathway may be important to the pathobiology of DYT1 dystonia.

Quite variable results have been reported from the neurochemical analyses of other DYT1 mouse models (Table 2). In transgenic mice generated by Shashidharan and colleagues (2005), decreased striatal DA levels were observed in mice with motor abnormalities (i.e., “affected” mice), whereas increased striatal DA levels were detected in mice without motor abnormalities (i.e., “unaffected” mice). Despite these differences in absolute DA levels, DOPAC/DA ratios were decreased in both “affected” and “unaffected” mice compared to wild-type controls, suggesting an overall decrease in DA turnover (Shashidharan et al., 2005). In heterozygote DYT1 knock-in mice, striatal HVA levels were found to be significantly decreased with no alterations of DA and DOPAC content (Dang et al., 2005) and DYT1 knock-down mice demonstrated significantly reduced DOPAC levels, with only a slight decrease in striatal DA (Dang et al. 2006). In addition to decreased striatal DA, decreases in 5-HT and 5-HIAA were also noted in hWT transgenic mice generated by Grundmann and colleagues (2007). In the brainstem only, a decrease in HVA levels and an increase in DOPAC, 5-HT and 5-HIAA levels were noted in hΔGAG3 transgenic mice (Grundmann et al., 2007). Taken together, these mixed neurochemical findings in DYT1 mouse models suggest that both mutant and WT torsinA can influence striatal dopaminergic neurotransmission.

In summary, our study has provided a vigorous analysis of the genetic, motoric, morphological, and neurochemical features of the hMT1 transgenic mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. The hMT1 model exhibits distinct motor and neurochemical phenotypes that result from the cellular burden of mutant torsinA. The increased DA turnover identified in hMT1 mice is noteworthy since tetrabenazine, a dopamine-depleting drug, has been used successfully in patients with generalized dystonia (Jankovic and Orman, 1988). Furthermore, mutant torsinA appears to interfere with the dopamine and vesicular monoamine transporters (Torres et al., 2004; Cao et al., 2005; Misbahuddin et al., 2005). Thus, the hMT1 mouse may be used to study the systems and cellular biology of torsinA and evaluate potential therapeutics for DYT1 dystonia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R01NS048458, R03NS050185). Transgenic mice were a kind gift from Drs. Xandra Breakefield and Nutan Sharma, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School, and monoclonal antibody D-M2A8 was generously supplied by Dr. Vijaya Ramesh, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson KD, Gunawan A, Steward O. Quantitative assessment of forelimb motor function after cervical spinal cord injury in rats: relationship to the corticospinal tract. Exp Neurol. 2005;194:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Ma Y, Okulski J, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Carbon M, Bressman SB, Eidelberg D. Decreased striatal D2 receptor binding in non-manifesting carriers of the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Neurology. 2005;64:347–349. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149764.34953.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augood SJ, Hollingsworth Z, Albers DS, Yang L, Leung JC, Muller B, Klein C, Breakefield XO, Standaert DG. Dopamine transmission in DYT1 dystonia: a biochemical and autoradiographical study. Neurology. 2002;59:445–448. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augood SJ, Keller-McGandy CE, Siriani A, Hewett J, Ramesh V, Sapp E, DiFiglia M, Breakefield XO, Standaert DG. Distribution and ultrastructural localization of torsinA immunoreactivity in the human brain. Brain Res. 2003;986:12–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcioglu A, Kim MO, Sharma N, Cha JH, Breakefield XO, Standaert DG. Dopamine release is impaired in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. J Neurochem. 2007;102:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshart M, Weber F, Jahn G, Dorsch-Häsler K, Fleckenstein B, Schaffner W. A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell. 1985;41:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakefield XO, Kamm C, Hanson PI. TorsinA: movement at many levels. Neuron. 2001;31:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressman SB, de Leon D, Raymond D, Ozelius LJ, Breakefield XO, Nygaard TG, Almasy L, Risch NJ, Kramer PL. Clinical-genetic spectrum of primary dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressman SB, Sabatti C, Raymond D, de Leon D, Klein C, Kramer PL, Brin MF, Fahn S, Breakefield X, Ozelius LJ, Risch NJ. The DYT1 phenotype and guidelines for diagnostic testing. Neurology. 2000;54:1746–1752. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.9.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AW, Bjelke B, Fuxe K. Motor response to amphetamine treatment, task-specific training, and limited motor experience in a postacute animal stroke model. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Gelwix CC, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA. Torsin-mediated protection from cellular stress in the dopaminergic neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3801–3812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5157-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon M, Su S, Dhawan V, Raymond D, Bressman S, Eidelberg D. Regional metabolism in primary torsion dystonia: effects of penetrance and genotype. Neurology. 2004;62:1384–1390. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120541.97467.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RJ, Lione LA, Humby T, Mangiarini L, Mahal A, Bates GP, Dunnett SB, Morton AJ. Characterization of progressive motor deficits in mice transgenic for the human Huntington’s disease mutation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3248–3257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03248.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier-Mariette C, Henry I, Montfort L, Capgras S, Forlani S, Muschler J, Nicolas JF. CpG content affects gene silencing in mice: evidence from novel transgenes. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R53. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-r53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, McNaught KS, Jengelley TA, Jackson T, Li J, Li Y. Generation and characterization of Dyt1 DeltaGAG knock-in mouse as a model for early-onset dystonia. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Pence MA, Li Y. Motor deficits and hyperactivity in Dyt1 knockdown mice. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DE, Gao X, Story GM, Anderson LI, Kucera J, Walro JM. Evaluation of nigrostriatal dopaminergic function in adult +/+ and +/- BDNF mutant mice. Exp Neurol. 2001;1:121–128. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S. Concept and classification of dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1988;50:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S, Bressman SB, Marsden CD. Classification of dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernagut PO, Diguet E, Stefanova N, Biran M, Wenning GK, Canioni P, Bioulac B, Tison F. Subacute systemic 3-nitropropionic acid intoxication induces a distinct motor disorder in adult C57Bl/6 mice: behavorial and histopathological characterization. Neuroscience. 2002;114:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernagut PO, Chalon S, Diguet E, Guilloteau D, Tison F, Jaber M. Motor behavior deficits and their histopathological and functional correlates in the nigrostriatal system of dopamine transporter knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2003;116:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00778-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LB, Davis JN. Clonidine impairs recovery of beam-walking after a sensorimotor cortex lesion in the rat. Brain Res. 1990;508:305–309. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild RE, Kim CE, Dauer WT. Loss of the dystonia-associated protein torsinA selectively disrupts the neuronal nuclear envelope. Neuron. 2005;48:923–932. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann K, Reischmann B, Vanhoutte G, Hubener J, Teismann P, Hauser TK, Bonin M, Wilbertz J, Horn S, Nguyen HP, Kuhn M, Chanarat S, Wolburg H, Van der Linden A, Riess O. Overexpression of human wildtype torsinA and human DeltaGAG torsinA in a transgenic mouse model causes phenotypic abnormalities. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J, Orman J. Tetrabenazine therapy of dystonia, chorea, tics, and other dyskinesias. Neurology. 1988;38:391–394. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Yan J, Zhao Y, Donahue LR, Beamer WG, Li X, Roe BA, Ledoux MS, Gu W. Carbonic anhydrase-related protein VIII deficiency is associated with a distinctive lifelong gait disorder in waddles mice. Genetics. 2005;171:1239–1246. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.044487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilby NJ, Leyser HM, Furner IJ. Promoter methylation and progressive transgene inactivation in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:103–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00029153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh YH, Rehfeld K, Ganetzky B. A Drosophila model of early onset torsion dystonia suggests impairment in TGF-beta signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2019–2030. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konakova M, Huynh DP, Yong W, Pulst SM. Cellular distribution of torsin A and torsin B in normal human brain. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:921–927. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.6.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konakova M, Pulst SM. Immunocytochemical characterization of torsin proteins in mouse brain. Brain Res. 2001;922:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuner R, Teismann P, Trutzel A, Naim J, Richter A, Schmidt N, Bach A, Ferger B, Schneider A. TorsinA, the gene linked to early-onset dystonia, is upregulated by the dopaminergic toxin MPTP in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGavern DB, Zoecklein L, Drescher KM, Rodriguez M. Quantitative assessment of neurologic deficits in a chronic progressive murine model of CNS demyelination. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:171–181. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught KS, Kapustin A, Jackson T, Jengelley TA, Jnobaptiste R, Shashidharan P, Perl DP, Pasik P, Olanow CW. Brainstem pathology in DYT1 primary torsion dystonia. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:540–547. doi: 10.1002/ana.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misbahuddin A, Placzek MR, Taanman JW, Gschmeissner S, Schiavo G, Cooper JM, Warner TT. Mutant torsinA, which causes early-onset primary torsion dystonia, is redistributed to membranous structures enriched in vesicular monoamine transporter in cultured human SH-SY5Y cells. Mov Disord. 2005;20:432–440. doi: 10.1002/mds.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlin SR, Konakova M, Pulst S, Chesselet MF. Development and anatomic localization of torsinA. Adv Neurol. 2004;94:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Martella G, Tscherter A, Bonsi P, Sharma N, Bernardi G, Standaert DG. Altered responses to dopaminergic D2 receptor activation and N-type calcium currents in striatal cholinergic interneurons in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostasy K, Augood SJ, Hewett JW, Leung JC, Sasaki H, Ozelius LJ, Ramesh V, Standaert DG, Breakefield XO, Hedreen JC. TorsinA protein and neuropathology in early onset generalized dystonia with GAG deletion. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;12:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(02)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Baxter MG, Petravicz J, Bragg DC, Schienda A, Standaert DG, Breakefield XO. Impaired motor learning in mice expressing torsinA with the DYT1 dystonia mutation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5351–5355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0855-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashidharan P, Sandu D, Potla U, Armata IA, Walker RH, McNaught KS, Weisz D, Sreenath T, Brin MF, Olanow CW. Transgenic mouse model of early-onset DYT1 dystonia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:125–133. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome EM, Cepeda IL, Sossi V, Doudet DJ. Evaluation of the integrity of the dopamine system in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease: small animal positron emission tomography compared to behavioral assessment and autoradiography. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:292–299. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen CE, Steinbusch HW, Angevaren M, Appels M, de Bruijn C, Prickaerts J, de Vente J. Behavioural correlates of striatal glial fibrillary acidic protein in the 3-nitropropionic acid rat model: disturbed walking pattern and spatial orientation. Neuroscience. 2001;105:153–167. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AD, Murray JD, Oberbauer AM. Transgene transmission to progeny by oMt1a-oGH transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 2005;14:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s11248-005-4349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Sweeney AL, Beaulieu JM, Shashidharan P, Caron MG. Effect of torsinA on membrane proteins reveals a loss of function and a dominant-negative phenotype of the dystonia-associated DeltaE-torsinA mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15650–15655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan A, Breakefield XO, Bhide PG. Developmental patterns of torsinA and torsinB expression. Brain Res. 2006:1073–1074. 139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RH, Brin MF, Sandu D, Gujjari P, Hof PR, Warren Olanow C, Shashidharan P. Distribution and immunohistochemical characterization of torsinA immunoreactivity in rat brain. Brain Res. 2001;900:348–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wietholter H, Eckert S, Stevens A. Measurement of atactic and paretic gait in neuropathies of rats based on analysis of walking tracks. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;32:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Gong S, Zhao Y, LeDoux MS. Developmental expression of rat torsinA transcript and protein. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]