Abstract

Background and objectives: Accurate assessment of the use of immunosuppressive medications is vital for observational analyses that are widely used in transplantation research. This study assessed the accuracy of three potential sources of maintenance immunosuppression data.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: This study investigated the agreement of immunosuppression information in directly linked electronic medical records for Medicare beneficiaries who received a kidney transplant at one center in 1998 through 2001, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) survey data, and Medicare pharmacy claims. Pair-wise, interdata concordance (κ) and percentage agreement statistics were used to compare immunosuppression regimens reported at discharge, and at 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation in each data source.

Results: Among 181 eligible participants, agreement between data sources for nonsteroid immunosuppression increased with time after transplantation. By 1-yr, concordance was excellent for calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil (κ = 0.79 to 1.00), and very good for azathioprine (κ = 0.73 to 0.85). Similarly, percentage agreement at 1 yr was 94.9 to 100% for calcineurin inhibitors, 91.1 to 95.7% for mycophenolate mofetil, and 87.5 to 92.8% for azathioprine. Widening the comparison time window resolved 33.6% of cases with discordant indications of calcineurin inhibitor and/or antimetabolite use in claims compared with other data sources.

Conclusions: This analysis supports the accuracy of the three sources of data for description of nonsteroid immunosuppression after kidney transplantation. Given the current strategic focus on reducing collection of data, use of alternative measures of immunosuppression exposure is appropriate and will assume greater importance.

Accurate assessment of immunosuppression is essential for transplant management and research. Clinical trials provide data on efficacy and safety in short-term experimental settings but not on long-term effectiveness and complications in practice (1). Large registries and administrative databases capture outcomes after kidney transplantation in “real-life” (2–4). The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) collects survey data on reported immunosuppression use that are integrated with administrative data from Medicare by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) (5). OPTN medication records are of limited scope, however (6), and reduction in data collection directed at lowering time and effort burdens on transplant centers has been deemed a key focus of the current OPTN strategic plan (7). Single-center records may be more detailed but are impractical to integrate across multiple centers unless stored in compatible electronic formats.

Administrative pharmacy claims databases, such as Medicare's, include records of dated prescriptions for large patient samples that are frequently used to assess medication use in studies of health care quality (8,9). Electronic claims records have been shown to reflect physician prescribing with greater than 99.6% accuracy (10–12). Very good to excellent levels of agreement between OPTN records and both Medicare and private-payer pharmacy claims for nonsteroid immunosuppression in kidney transplant recipients have been reported (13,14). The OPTN and Medicare pharmacy claims have not been compared with clinical medical records for immunosuppression.

To assess the validity of Medicare pharmacy claims, OPTN data, and single-center medical records for immunosuppression in kidney transplant recipients, we linked electronic medical records from a transplant program to OPTN and Medicare pharmacy records. We assessed the agreement of these three data sources for calcineurin inhibitors, adjunctive agents, and corticosteroids at discharge and 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation.

Concise Methods

Data Sources and Participant Selection

After institutional review board, National Institutes of Health, and USRDS approvals, recipient identifier numbers from the electronic databases of the Washington University kidney transplant program were linked using Social Security numbers and dates of birth to unique patient identifiers by the USRDS. The USRDS packages national OPTN data for kidney transplants performed in the United States as well as billing claims for Medicare-insured kidney transplant recipients. Identifier linkage was performed at USRDS headquarters, and all protected health information was removed after linkage to create anonymous analytic data sets merged to patient-specific USRDS identification numbers. Match validation included confirmation of agreement of transplant dates in the clinical record and OPTN data. Baseline recipient demographic and transplant data were drawn from the Transplant Registration Form as collected by the OPTN.

Patients who received a transplant at Washington University from 1998 through 2001 with Medicare as the primary payer were considered as candidates for inclusion. Medicare payer status was defined on the basis of “primary payer” indication in the “Payhist” file of the USRDS. To ensure complete Medicare billing records, we also required that the Medicare payment for the initial transplant hospitalization be at least $15,000, as described previously (15). In cases when a single patient received more than one transplant during the study period, we included only the most recent event.

We studied reported use of oral immunosuppressive medications at transplant discharge and at 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation. Drug-specific, interdata source agreement was considered pair-wise among the OPTN record, the Washington University electronic medical record, and Medicare claims. At each time point, analytic samples were restricted to patients with collected information on maintenance immunosuppression in the data sources under comparison. The availability of maintenance immunosuppression data was defined by recorded use of an oral formulation of at least one of the following drugs: Tacrolimus, cyclosporine, sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), azathioprine, or corticosteroids. No patients are maintained entirely free of immunosuppression at our center except recipients from an identical twin donor.

Ascertainment of Medication Use

We ascertained OPTN reporting of immunosuppressive medication use from the Kidney Transplant Recipient Registration Form at transplant discharge and the Recipient Follow-up Forms at 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation. Immunosuppression use in the Washington University medical record was obtained from the Organ Transplant Tracking Record (HKS Medical information Systems, Omaha, NE). Medicare pharmacy claims were identified by Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System among claims codes for which Medicare paid at least a portion of submitted charges. Drug-specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes included the following: Tacrolimus, J7507 and J7508; cyclosporine, C9438, J7502, J7515, J7503, K0121, and K0418; sirolimus, J7520 and C9020; MMF, J7517, K0412, and J7518; azathioprine, J7500, C9436, and K0119; and corticosteroids, J7506, J7509, J7510, K0125, K0166, and K0167.

The OPTN surveys transplant centers for immunosuppression use at transplant discharge, 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation, and annually. For all comparisons, the date of transplantation and each time point was defined per OPTN reporting. Specifically, the date of the “6-mo” anniversary was the date of the Kidney Transplant Recipient Follow-up Form within 182 ± 60 d after transplant. The date of the “1-yr” anniversary was the date of the form submitted to the OPTN from 305 d (midway between 6 mo and 1 yr) and 518 d (midway between 1 and 2 yr) after transplantation.

We searched for immunosuppression records in the Organ Transplant Tracking Record at Washington University within a window spanning ±30 d of the OPTN-defined follow-up date. Because Medicare pharmacy benefits cover 30-d drug disbursements, Medicare claims were considered to indicate use at a given follow-up time when submitted within ±30 d of the corresponding OPTN-defined follow-up date (16). Recognizing that patients may refill prescriptions at longer-than-ideal intervals, an additional analysis considered pharmacy claims submitted within ±90 d of the date of interest.

Statistical Analyses

Prevalence of immunosuppressive use according to each data source is reported as counts and proportions. We compared interdata source agreement by the κ concordance statistic, a measure of agreement that adjusts for the distribution expected by chance (17). Concordance was interpreted by established grading criteria: κ < 0.20, poor; κ = 0.20 to 0.39, fair; κ = 0.40 to 0.59, moderate; κ = 0.60 to 0.79, very good; and κ > 0.80, excellent (17). We also computed percentage agreement between compared data sources, defined as the proportion of the sample that has been similarly classified by both sources.

Examination of Discordance for Claims

We examined the disagreement between claims and the OPTN or medical record by classifying discordant cases within immunosuppression classes (calcineurin inhibitors—cyclosporine and tacrolimus, and antimetabolites—azathioprine and MMF). We identified the percentage of patients who had discordant indications of calcineurin inhibitor and/or antimetabolite use in claims compared with the OPTN or the medical record, respectively, and who had concordant claims after expansion of the ascertainment window within claims to ±90 d. When this condition was not satisfied, we obtained counts of those with no drug-specific claims but with claims for another drug within the same class at the study time of interest and no claims for either drug in the class of interest at the relevant study point.

Results

Patients

During 1998 to 2001, 181 patients received a renal allograft with Medicare as the primary payer at Washington University and were alive with a functioning graft at discharge. There were no identical twin transplants at our center in the study period. There were also no clinical trials in progress at Washington University during 1998 through 2001 that supplied oral immunosuppression to participants as unbilled study medications. Of the sample of 181 patients, 172 and 166 patients were alive with graft function at 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation, respectively (Table 1). At the time of transplant discharge, 177 (97.8%) patients had available data on maintenance immunosuppression use in OPTN, 137 (75.7%) had discharge immunosuppression entered in the electronic medical record, and 65 (35.9%) had Medicare claims for at least one immunosuppressive drug. Capture of immunosuppression data was lowest in the OPTN survey at the 6-mo time point, whereas capture progressively increased with time after transplantation in the medical records and in claims. At the 1-yr anniversary, immunosuppression entry in the electronic record was found for 95.8% of patients who were alive with function. Deficiencies in the capture of immunosuppression use in the electronic medical record for individual patients were dominantly confined to the first year of the study period, as the system was launched: 36 (81.8%) of 44, 18 (62.0%) of 29, and two (28.6%) of seven cases for whom we lacked electronic medical records on immunosuppression at discharge, 6 mo, and 1 yr, respectively, occurred in 1998.

Table 1.

Counts of participants with available information on maintenance immunosuppression by data source across the study time points and as fractions of sample alive with function

| Time after Transplantation | Alive with Graft Functiona | OPTN Forms Submittedb | Subsets of Sample Alive with Graft Function, Defined by Availability of Maintenance Immunosuppression Records in the Indicated Data Source(s) at the Study Time Point(s) (n [%])c

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTN | MR | CLM | OPTN and MR | OPTN and CLM | MR and CLM | Any | All | |||

| Discharge | 181 | 181 | 177 (97.8) | 137 (75.7) | 65 (35.9) | 137 (75.7) | 65 (35.9) | 50 (27.6) | 177 (97.8) | 50 (27.6) |

| 6 mo | 172 | 163 | 118 (68.6) | 143 (83.1) | 66 (38.4) | 116 (67.4) | 46 (26.7) | 57 (33.1) | 153 (89.0) | 45 (26.2) |

| 1 yr | 166 | 163 | 140 (84.3) | 159 (95.8) | 68 (41.0) | 138 (83.1) | 56 (33.7) | 66 (39.8) | 162 (97.6) | 55 (33.1) |

| All | 113 | 122 | 49 | 111 | 35 | 36 | 34 | |||

Counts from the total sample who received a transplant in 1998 through 2001 with Medicare as the primary insurer at the time of transplantation, regardless of the availability of immunosuppression information.

Counts of patients with any survey data submitted to the OPTN (not strictly immunosuppression records) at time point of interest.

Percentage of the total sample who were alive with function at study point of interest and had immunosuppression records in the indicated source.

Table 2 provides the distribution of patient characteristics in the total sample of transplant recipients and in the analytic subsamples defined by the availability of maintenance immunosuppression records at the study times of interest. With the exception of year of transplantation, the main sample and subsamples had similar distributions of characteristics.

Table 2.

Distributions of demographic traits in the total sample of transplant recipients and in analytic subsamples defined by the availability of source-specific immunosuppression informationa

| Parameter | Total Sample of Transplant Recipients(N = 181) | Analytic Samples Defined by the Presence of Immunosuppression Information in the Data Sources of Interest (n [%])b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTN, MR, or CLM(n = 178) | OPTN and MR(n = 150) | OPTN and CLM(n = 82) | MR and CLM(n = 79) | ||

| Recipient traits | |||||

| female gender | 77 (42.5) | 74 (41.6) | 62 (41.3) | 34 (41.5) | 30 (38.0) |

| race | |||||

| black | 56 (30.9) | 55 (30.9) | 44 (29.3) | 25 (30.5) | 25 (31.7) |

| white | 124 (68.5) | 122 (68.5) | 105 (70.0) | 56 (68.3) | 53 (67.1) |

| other | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| age (yr) | |||||

| 0 to 18 | 5 (2.8) | 5 (2.8) | 4 (2.7) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| 19 to 30 | 23 (12.7) | 23 (12.9) | 18 (12.0) | 13 (15.9) | 13 (16.5) |

| 31 to 44 | 47 (26.0) | 46 (25.8) | 40 (26.7) | 25 (30.5) | 22 (27.9) |

| 45 to 59 | 48 (26.5) | 47 (26.4) | 40 (26.7) | 19 (23.2) | 19 (24.1) |

| ≥60 | 58 (32.0) | 57 (32.0) | 48 (32.0) | 24 (29.3) | 24 (30.4) |

| BMI category (kg/m2) | |||||

| <10 or missing | 52 (28.7) | 52 (29.2) | 50 (33.3) | 29 (35.4) | 28 (35.4) |

| nonoverweight, nonobese (BMI <25) | 64 (35.4) | 62 (34.8) | 46 (30.7) | 28 (34.2) | 26 (32.9) |

| overweight (BMI ≥25 and <30) | 39 (21.6) | 38 (21.4) | 31 (20.7) | 16 (19.5) | 15 (19.0) |

| obese (BMI ≥30) | 26 (14.4) | 26 (14.6) | 23 (15.3) | 9 (11.0) | 10 (12.7) |

| Primary cause of ESRD | |||||

| diabetes | 37 (20.4) | 37 (20.8) | 29 (19.3) | 21 (25.6) | 21 (26.6) |

| hypertension | 14 (7.7) | 14 (7.9) | 10 (6.7) | 6 (7.3) | 6 (7.6) |

| glomerulonephritis | 13 (7.2) | 13 (7.3) | 10 (6.7) | 6 (7.3) | 6 (7.6) |

| other | 35(19.3) | 33 (18.5) | 25 (16.7) | 13 (15.9) | 10 (12.7) |

| unknown | 72 (39.8) | 71 (39.9) | 66 (44.0) | 34 (41.5) | 34 (43.0) |

| Pretransplantation comorbidities | |||||

| diabetes | 53 (29.3) | 53 (30.2) | 44 (29.3) | 27 (32.9) | 27 (34.1) |

| cerebral vascular disease | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| malignancy | 8 (4.4) | 8 (4.6) | 8 (5.3) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.9) |

| peripheral vascular disease | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.3) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.9) |

| angina | 8 (4.4) | 8 (4.6) | 7 (4.7) | 4 (4.9) | 4 (5.2) |

| Deceased donor type | 143 (79.0) | 140 (78.7) | 118 (78.7) | 63 (76.8) | 60 (76.0) |

| Delayed graft function | 11 (6.1) | 10 (5.6) | 8 (5.3) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Year of transplantation | |||||

| 1998 | 45 (24.9) | 44 (24.7) | 18 (12.0) | 18 (22.0) | 17 (21.5) |

| 1999 | 38 (21.0) | 38 (21.4) | 36 (24.0) | 18 (22.0) | 17 (21.5) |

| 2000 | 46 (25.4) | 45 (25.3) | 45 (30.0) | 23 (28.1) | 23 (29.1) |

| 2001 | 52 (28.7) | 51 (28.7) | 51 (34.0) | 23 (28.1) | 22 (27.9) |

BMI, body mass index; CLM, Medicare pharmacy billing claims; MR, medical record; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

Refers to the presence of immunosuppression information at at least one study time point. Significance test were not performed as groups are not mutually exclusive.

Agreement of Immunosuppression Records

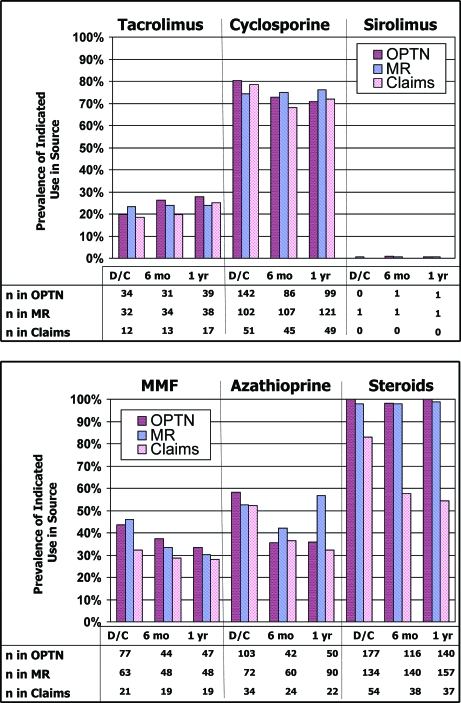

The immunosuppression use indicated in the OPTN survey, medical records, and Medicare pharmacy claims at each study point is shown in Figure 1. The denominator reflects the number of participants with available immunosuppression information in the relevant data source at the study time of interest, as per Table 1. Table 3 displays pair-wise comparisons of interdata concordance in the analytic samples. Cyclosporine was the most commonly prescribed calcineurin inhibitor at this center, indicated in 68 to 80% of analytic samples across the study compared with tacrolimus use in 18 to 28%. Pair-wise interdata source concordance was excellent or near excellent for tacrolimus across the study (κ = 0.80 to 1.00). For cyclosporine, concordance was excellent at discharge and 1 yr (κ = 0.81 to 0.92) and moderate to excellent at 6 mo (κ = 0.59 to 0.82).

Figure 1.

Indicated use of immunosuppressive medications in the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) survey, medical records (MR), and Medicare pharmacy claims across the study time points. Denominator for prevalence calculations reflects the number of patients with available maintenance immunosuppression records in the data source of interest at each study time point and thus varies by data source. D/C, discharge; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Table 3.

Concordance statistics (κ) for indicated use of individual immunosuppressive drugsa

| Drug | OPTM/MR | ±30 D of Follow-up Date Window for Claims Ascertainment

|

±90 D of Follow-up Date Window for Claims Ascertainment

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTN/CLM | MR/CLM | OPTN/CLM | MR/CLM | ||

| Cyclosporine | |||||

| discharge | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.92) | 0.81 (0.63 to 0.99) | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.00) | 0.90 (0.76 to 1.00) | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.00) |

| 6 mo | 0.82 (0.71 to 0.94) | 0.59 (0.35 to 0.82) | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.93) | 0.82 (0.62 to 1.00) | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.00) |

| 1 yr | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.96) | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.00) | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.00) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| Tacrolimus | |||||

| discharge | 0.88 (0.78 to 0.97) | 0.90 (0.76 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.90 (0.76 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| 6 mo | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.97) | 0.80 (0.59 to 1.00) | 0.84 (0.66 to 1.00) | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.00) | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.00) |

| 1 yr | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| MMF | |||||

| discharge | 0.69 (0.57 to 0.81) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.83) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.00) | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.86) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| 6 mo | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.92) | 0.74 (0.52 to 0.95) | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.85) | 0.80 (0.60 to 0.99) | 0.73 (0.54 to 0.92) |

| 1 yr | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.98) | 0.79 (0.62 to 0.96) | 0.85 (0.71 to 0.99) | 0.84 (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.00 |

| Azathioprine | |||||

| discharge | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.75) | 0.38 (0.16 to 0.60) | 0.84 (0.70 to 0.99) | 0.48 (0.27 to 0.70) | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.00) |

| 6 mo | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.94) | 0.80 (0.62 to 0.99) | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.92) | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.00) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.00) |

| 1 yr | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.94) | 0.73 (0.54 to 0.91) | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.95) | 0.85 (0.70 to 0.99) | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.00) |

| Sirolimus | |||||

| discharge | b | b | b | b | b |

| 6 mo | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | b | b | b | b |

| 1 yr | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | b | b | b | b |

Analytic samples were defined by the availability of maintenance immunosuppression information in the data sources under comparison at the study time points of interest. κ grading criteria as follows: κ < 0.20, poor; κ = 0.20 to 0.39, fair; κ = 0.40 to 0.59, moderate; κ = 0.60 to 0.79, very good; κ > 0.80, excellent (17).

κ not calculable because of absence of any reported drug-specific use in one or both comparison groups.

Sirolimus was used in only 0.9 and 0.7% of participants at 6 mo and 1 yr, respectively, according to the OPTN (Figure 1). Our medical records recorded sirolimus use in 0.6 to 0.7%. No Medicare claims for sirolimus were detected at any time point. Percentage agreement was perfect or nearly perfect for all sirolimus comparisons. Thus, the few patients with OPTN or medical record indications of sirolimus use but without drug-specific claims did not have Medicare claims for any maintenance immunosuppression and were not included in the agreement computations.

Reported use of azathioprine ranged from 58% in the OPTN at discharge to 36% at both subsequent time points and showed a similar decrease over time after transplantation in the claims (52 to 32%). The prevalence of azathioprine use in the medical records decreased from 52% at discharge to 42% at 6 mo and then was 57% at 1 yr (Figure 1). MMF use was indicated in 28 to 46% of patients across the study. Concordance was excellent for azathioprine and MMF in the OPTN versus the medical record at 6 mo and 1 yr after transplantation, for both antimetabolites in the medical record compared with Medicare claims at discharge and 1 yr after transplant, and for azathioprine in Medicare claims compared with the OPTN at 6 mo (κ = 0.80 to 0.96). Concordance estimates ranged from fair for azathioprine at discharge in the OPTN versus Medicare claims (κ= 0.38), to very good for all remaining comparisons (κ = 0.62 to 0.79). Expansion of the detection window in Medicare claims from ±30 to ±90 d improved concordance of claims with both medical records and the OPTN.

According to the OPTN survey, 98 to 100% of patients were taking corticosteroids at each time point (Figure 1). These estimates were similar to reported 97 to 99% use in the medical record; however, the fraction of patients with Medicare claims for corticosteroids fell from 83% at transplant discharge to <60% at 6 mo and 1 yr. κ adjusts for the distribution expected by chance and is not meaningful when there is an extremely high probability of classification according to one data source under comparison (e.g., corticosteroids use according to the OPTN or medical record); therefore, corticosteroid agreement was described by percentage agreement (Table 4). The OPTN and medical records had near-perfect percentage agreement across all time points (98 to 99%). Whereas the percentage agreement was 83% for claims versus OPTN and 80% for Medicare claims versus medical records at discharge, the percentage agreement decreased at 6 mo to 61 and 54%, respectively, and remained low at 1 yr after transplantation (57 and 55%, respectively).

Table 4.

Percentage agreement for indicated use of individual immunosuppressive drugs in compared data sourcesa

| Drug | OPTN/MR | ±30 D of Follow-up Date Window for Ascertainment

|

±90 D of Follow-up Date Window for Ascertainment

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTN/CLM | MR/CLM | OPTN/CLM | MR/CLM | ||

| Cyclosporine | |||||

| discharge | 92.7 | 93.8 | 96.0 | 96.9 | 98.0 |

| 6 mo | 93.1 | 82.6 | 89.5 | 93.5 | 96.5 |

| 1 yr | 94.9 | 96.4 | 97.0 | 98.3 | 100.0 |

| Tacrolimus | |||||

| discharge | 95.6 | 96.9 | 100.0 | 96.9 | 100.0 |

| 6 mo | 94.8 | 93.5 | 94.7 | 95.7 | 96.5 |

| 1 yr | 97.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| MMF | |||||

| discharge | 84.7 | 83.1 | 98.0 | 84.6 | 100.0 |

| 6 mo | 91.4 | 89.1 | 84.2 | 91.3 | 87.7 |

| 1 yr | 95.7 | 91.1 | 94.0 | 92.9 | 95.5 |

| Azathioprine | |||||

| discharge | 81.0 | 69.2 | 92.0 | 75.4 | 96.0 |

| 6 mo | 92.2 | 91.3 | 87.7 | 93.5 | 96.5 |

| 1 yr | 92.8 | 87.5 | 90.9 | 92.9 | 95.5 |

| Sirolimus | |||||

| discharge | 99.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 6 mo | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 1 yr | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Prednisone | |||||

| discharge | 97.8 | 83.1 | 80.0 | 97.8 | 86.0 |

| 6 mo | 98.3 | 60.9 | 54.4 | 73.9 | 71.9 |

| 1 yr | 98.6 | 57.4 | 54.6 | 66.1 | 68.2 |

Analytic samples were defined by the availability of maintenance immunosuppression information in the data sources under comparison at the study time points of interest. Percentage agreement indicates the proportion of the analytic sample that has been similarly classified by both sources.

Examination of Discordance

Table 5 categorizes cases with discordant indications of calcineurin inhibitor and/or antimetabolite use in the claims compared with the OPTN or medical records by candidate explanations for disagreement. The most common type of discordance was too narrow of a window when extracting claims. Widening the window for claims ascertainment to ±90 d resolved 36.5% of discordant cases, more with medical records (50%) than OPTN (28%). The presence of the other drug of the same class of immunosuppression in the claims accounted for 32% of discordance. Overall, this was more common in cases of discordance of claims with the OPTN (41%) than with medical records (18%).

Table 5.

Patterns of immunosuppression claims in patients with discordant indications of calcineurin inhibitor and antimetabolite use in claims compared with OPTN and the MRa

| Parameter | Discharge (n [%])

|

6 Mo (n [%])

|

1 Yr (n [%])

|

All Study Time Points (n [%])

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTNb | MRb | OPTNb | MRb | OPTNb | MRb | OPTNb | MRb | Total | |

| Total discordant | 37 (100) | 7 (100) | 20 (100) | 25 (100) | 14 (100) | 12 (100) | 71 (100) | 44 (100) | 115 (100) |

| Concordant claim present within an extended window of ±90 d | 7 (18.9) | 4 (57.1) | 8 (40.0) | 12 (48.0) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (50) | 20 (28.2) | 22 (50.0) | 42 (36.5) |

| Claim for another drug of same class at corresponding observation timec | 21 (56.8) | 1 (14.3) | 6 (30.0) | 6 (24.0) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (8.3) | 29 (40.8) | 8 (18.2) | 37 (32.2) |

| No claim for any drug within class at corresponding observation timec | 9 (24.3) | 2 (28.6) | 6 (30.0) | 7 (28.0) | 7 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) | 22 (31.0) | 14 (31.8) | 36 (31.3) |

Calcineurin inhibitor class comprises cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Antimetabolite class comprises azathioprine and MMF.

Data source compared with claims.

The window for claims ascertainment taken as ±30 d of the corresponding follow-up date, as per definition in primary analyses.

Discussion

Accurate methods for assessing immunosuppression facilitate study of long-term effectiveness and safety of this critical component of transplant care. The OPTN survey provides an important national source of immunosuppression information; however, concerns for the time and effort burdens that are imposed on transplant centers by data collection have prompted focus on data reduction as part the current OPTN strategic plan, with expectations that decreased reporting will allow staff to devote more time to patient care (7). In February 2007, the OPTN enacted policy for a 40% decrease in required elements on reporting forms, including a 77% cutback in cumulative immunosuppression reporting requirements (7,18). The policy limits immunosuppression reporting to transplant registration and the 1-yr follow-up, eliminating the 6-mo and all annual immunosuppression surveys beyond the first year. Furthermore, recent public comment statements co-authored by the presidents of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons and American Society of Transplantation recommend that the OPTN cease collection of any data concerning immunosuppression (18,19). We performed a three-armed examination of linked OPTN data, single-center electronic medical records, and Medicare pharmacy claims for immunosuppression among Medicare-insured kidney transplant recipients to assess the agreement of these data sources and thereby evaluate the utility of novel sources as supplements to OPTN immunosuppression surveys.

We found that concordance of immunosuppressive drugs in the OPTN survey, electronic medical records, and Medicare pharmacy claims was very good to excellent for calcineurin inhibitors and MMF. Concordance was moderate to excellent for azathioprine. Overall, the absolute differences in reported nonsteroid immunosuppression use between the OPTN and medical record were low (0.4 to 2.2%).

Use of Medicare pharmacy claims to analyze immunosuppression is a relatively new method. Although the agreement patterns of claims versus the OPTN and the medical record for nonsteroid immunosuppression were similar to those of the OPTN versus the medical record, we observed general lower prevalence estimates of individual drug use in Medicare claims compared with the other data sources. A recent comparison of a large electronic pharmacy claims database with written prescriptions found negligible error rates of 0.02% for drug dispensed (10). Lau et al. (11) and Boethius et al. (12) independently found pharmacy records and claims to have near-perfect agreement with home inventories; however, a full year of data were required for the highest level of agreement. A lengthened ascertainment window increased the concordance of claims with the OPTN and medical record in this study and resolved 36.5% of total cases when Medicare claims were discordant for calcineurin inhibitors or antimetabolites. Physician-directed dosage reductions that are communicated without written prescriptions or missed doses may be explanations, allowing a month's supply of medication to cover more than the expected 30 d.

Pair-wise data concordance showed trends toward improvement at 1 yr compared with earlier time points. Perfect to near-perfect concordance and percentage agreement of claims and medical records was observed at 1 yr for calcineurin inhibitors and adjuncts when the ±90 d window for claims was used. A number of factors may explain the heightened agreement at 1 yr. Switching of immunosuppressive agents is common early after transplantation, making mismatches more likely. The 1-yr transplant anniversary is a milestone frequently accompanied by a clinic visit at the center. Center visits allow identification of noncenter physician prescribing, record updates, and inquiries into medication compliance.

Observed patterns of discordance within immunosuppression classes in this study support the accuracy of Medicare claims as measures of drug use. The most common cause (36.5%) of discordance of Medicare claims with other data was the narrowness of the capture window. In nearly an additional one third of discordant cases, there were pharmacy claims for a different drug of the same class. Given the reported accuracy of pharmacy claims data (10–12), it is likely that when a pharmacy claim indicates purchase, a drug was dispensed despite disagreement with the medical record or OPTN. This type of discordance may result from immunosuppression changes by outside-of-center physicians that are not reported to the center or to recording errors. Furthermore, when there is no pharmacy claim for any drug within a reportedly prescribed immunosuppression class, noncompliance is possible, although alternative insurance or use from “oversupply” may also contribute.

Although high levels of agreement of pharmacy claims with both the OPTN and medical records were observed for most agents examined here, agreement was uniquely low for corticosteroids, with a pattern of progressively lower prevalence in Medicare claims over time after transplantation. We observed similar patterns in a study comparing national Medicare pharmacy claims and the OPTN without a medical record arm (13). Possible explanations include class-related differences in perceptions of medication importance (20) and consequent differential compliance and/or longer-than-expected filling intervals as a result of verbally communicated dosage reductions over time that produce temporary oversupply.

The data source examined in this study is a unique construction in which OPTN survey data, electronic medical records, and pharmacy claims were linked at the patient level. Capture of immunosuppression use in the medical record was lowest at discharge because data entry into the electronic system at our center was less frequent during hospitalizations than during ambulatory encounters, particularly as the system came into use. Medicare claims for maintenance immunosuppression occur in only a subset of Medicare-insured transplant recipients, because Medicare coverage for immunosuppression requires purchase of optional Part B insurance, and a substantial fraction of Medicare-beneficiaries do not use Part B (13). Although our study is limited by the inability to use a single sample for all comparisons, the subsamples were representative of the full sample of transplant recipients. Our samples were relatively small, and findings may not generalize to the billing claims of other reimbursement systems such as private-payer insurance; however, successful linkage of electronic medical records with OPTN data and Medicare claims demonstrates a method that may be expanded to determine the agreement of data from other centers and insurance providers and thereby allow assessment of the robustness of our findings.

The lack of a true “gold standard” measure of immunosuppression use to compare the accuracy of medical records, the OPTN survey, and Medicare claims is an important limitation of this study. Although nothing is more accurate than an audit of patients’ households (21), such data collection is prohibitively expensive and intrusive. Despite its limitations, our understanding of data that theoretically are well suited and technically accessible for observational study of immunosuppression has been advanced.

Conclusion

We observed generally good to excellent agreement of Medicare pharmacy claims, OPTN data, and single-center electronic medical records for use of nonsteroid immunosuppression in renal transplant recipients, supporting the utility of all three measures for management and research. Although our analysis does not prove the superiority of any one data source, it supports claims data as a better indicator of immunosuppressive use in some cases. Pharmacy claims data compose the only source of immunosuppression information that is readily available on a large scale, measured on a continuous interval, and includes dosing information. It is also possible that pharmacy claims can be used to identify noncompliance, although this must be examined in further study. Given the current OPTN strategic focus on reducing collection of immunosuppression data, sources of immunosuppression information such as pharmacy claims and electronic medical records will assume greater importance.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Buchanan received support from a Public Policy Fellowship from the American Society of Transplantation. Dr. Brennan received support from a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), K24-DK002886. Dr. Lentine received support from a grant from the NIDDK, K08-DK073036. Additional support was provided to Dr. Schnitzler from Novartis Pharma.

A portion of this work was presented in abstract form at the American Transplant Congress; May 5 through 9, 2007; San Francisco, CA.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Data reported here were supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

References

- 1.Davidson MH: Differences between clinical trial efficacy and real-world effectiveness. Am J Manag Care 12: S405–S411, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, Distant DA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Metzger RA, Ojo AO, Port FK: Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA 294: 2726–2733, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Lowell J, Schnitzler MA: Long-term outcome of gastrointestinal complications in renal transplant patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transpl Int 17: 609–616, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Renal Data System: Researcher's Guide to the USRDS Database, 2006. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/research.htm. Accessed June 1, 2007

- 6.United States Renal Data System Annual Data Report, 2006. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/2006/rg/C_Data_File_Descriptions.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2007

- 7.Fewer Required Elements on OPTN/UNOS Forms. OPTN News Release, February 7, 2007. Available at: http://www.optn.org/SharedContentDocuments/Data_Reduction_Flier.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2007

- 8.Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, Fleming B, Houck PM, Kussmaul AE, Nilasena DS, Ordin DL, Arday DR: Quality of medical care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries: A profile at state and national levels. JAMA 284: 1670–1676, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM: Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit health plans enrolling Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med 118: 1392–1400, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy AR, O'Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D: Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 10: 67–71, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau HS, de Boer A, Beuning KS, Porsius A: Validation of pharmacy records in drug exposure assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 50: 619–625, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boethius G: Recording of drug prescriptions in the county of Jamtland, Sweden. II. Drug exposure of pregnant women in relation to course and outcome of pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 12: 37–43, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stirnemann PM, Takemoto SK, Schnitzler MA, Brennan DC, Abbott KC, Salvalaggio P, Burroughs TE, Gavard JA, Willoughby LM, Lentine KL: Agreement of immunosuppression regimens described in Medicare pharmacy claims with the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network survey. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2299–2306, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilmore AS, Helderman JH, Ricci JF, Ryskina KL, Feng S, Kang N, Legorreta AP: Linking the US transplant registry to administrative claims data: Expanding the potential of transplant research. Med Care 45: 529–536, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiting JF, Woodward RS, Zavala EY, Cohen DS, Martin JE, Singer GG, Lowell JA, First MR, Brennan DC, Schnitzler MA: Economic cost of expanded criteria donors in cadaveric renal transplantation: Analysis of Medicare payments. Transplantation 70: 755–760, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Billing for immunosuppressive drugs furnished to transplant patients. In: Medicare Hospital Manual, Baltimore, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2001, Section 439, pp 8–9

- 17.Altman DG: Practical Statistics for Medical Research, London, Chapman and Hall, 1991, pp 404

- 18.Cosimi AB, Fine RN: Proposed modification to data elements on UNetSM Transplant Candidate Registration (TCR), Transplant Recipient Registration (TRR), Transplant Recipient Follow-up (TRF), and Post-Transplant Malignancy (PTM) forms by the Policy Oversight Committee, June 12, 2006. Available at: http://asts.org/advocacy/regulatory.aspx. Accessed October 12, 2007

- 19.Matas AJ, Cripppin JS: Public comment concerning modifications to data elements on UNet Transplant recipient follow-up (TRF) form (Policy Oversight Committee), December 12, 2006. Available at: http://asts.org/advocacy/regulatory.aspx. Accessed October 12, 2007

- 20.Butler JA, Peveler RC, Roderick P, Smith PW, Horne R, Mason JC: Modifiable risk factors for non-adherence to immunosuppressants in renal transplant recipients: A cross-sectional study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 3144–3149, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang JC, Tomlinson G, Naglie G: Medication lists for elderly patients: Clinic-derived versus in-home inspection and interview. J Gen Intern Med 16: 112–115, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]