Abstract

Background and objectives: Impaired kidney function is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease and may progress over time to end-stage renal disease. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism has been implicated as a possible cause of these complications, but lipoproteins have not been described at the earliest stages of kidney disease.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: This study examined cross-sectional associations of serum cystatin C with conventional lipid measurements and detailed nuclear magnetic resonance lipoprotein measurements in the community-based Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. A total of 5109 participants with estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were included in analyses.

Results: Adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, BP, smoking, medications, body mass index, and albuminuria, greater cystatin C concentrations were associated with progressively unfavorable lipid and lipoprotein concentrations, including greater triglyceride concentration (+22 mg/dl, comparing fifth versus first quintiles of cystatin C) and lesser high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration (−7 mg/dl) but not with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol measured using conventional methods. When low-density lipoprotein particle subclasses were examined in more detail using nuclear magnetic resonance, greater cystatin C was associated with greater concentrations of atherogenic small low-density lipoprotein particles (+63 nmol/L) and intermediate-density lipoprotein particles (+6 nmol/L) and with a decrease in mean low-density lipoprotein particle size.

Conclusions: Lipoprotein abnormalities are present with milder degrees of renal impairment than previously recognized, and abnormalities in low-density lipoprotein particle distribution may not be appreciated using conventional lipid measurements. These abnormalities may contribute to kidney disease progression and/or cardiovascular disease.

Impaired kidney function is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease (1,2) and may progress over time to ESRD. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism has been implicated as a possible cause of these complications (3,4). Moderate chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with elevated triglyceride and diminished HDL cholesterol concentrations (3–8). Total and LDL cholesterol concentrations have generally been reported to be unaltered in the setting of CKD (5–7); however, conventional lipid measurements do not fully capture relevant changes in lipoprotein distribution, particularly differences in LDL particle number and size (3,4). Moreover, lipid and lipoprotein concentrations have not been described at the earliest stages of kidney disease (before GFR falls below 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), when the pathophysiologic processes that lead to atherosclerosis and CKD could already be developing.

We examined associations of serum cystatin C with detailed nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) lipoprotein measurements in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Only participants with estimated GFR (eGFR) ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were included in analyses, and individuals with clinical cardiovascular disease were excluded from MESA participation. Elevated serum cystatin C detects mild impairment of kidney function with greater sensitivity than eGFR calculated from serum creatinine (9–11). NMR quantifies lipoprotein particles by size, allowing characterization of particle number and size within classes of lipoproteins.

Concise Methods

Study Population

MESA is a prospective cohort study designed to investigate the prevalence, correlates, and progression of subclinical cardiovascular disease. As described in detail elsewhere, 6814 community-dwelling residents aged 45 to 84 were recruited between 2000 and 2002 at six centers across the United States (12). Individuals with previous clinical cardiovascular disease were excluded. Detailed data describing demographics, comorbidities, and medications were collected at enrollment, and each participant gave baseline blood and urine samples. Study protocols were approved by the institutional review board at each participating institution, and all MESA participants granted informed consent.

Measurements of cystatin C and NMR lipoproteins were available for 6752 (99%) MESA participants. Of these, 683 (10%) had an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, calculated from serum creatinine using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula. These 683 participants were excluded from analyses to focus on lipoprotein abnormalities that were present before recognition of clinical CKD, as defined by current clinical guidelines (13). Because lipid-lowering therapy strongly affects lipid and lipoprotein concentrations, we also excluded participants who reported use of any lipid-lowering agent (hepatic hydroxymethyl glutaryl–CoA reductase inhibitors, fibrates, niacin, and/or bile acid sequesters; n = 913). In addition, we excluded one MESA participant with a urine albumin-creatinine ratio ≥3000 mg/g, because the nephrotic syndrome is known to be associated with severe lipoprotein abnormalities, and those for whom any of the covariates described next were not documented (n = 46). A total of 5109 participants were included in analyses.

Cystatin C

Cystatin C assays were performed using serum that was drawn in the morning and stored at −70°C. A BNII nephelometer (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL) measured cystatin C with a particle-enhanced immunonepholometric assay (N Latex Cystatin C; Dade-Behring) (14). Polystyrene particles were coated with mAb to cystatin C that agglutinate in the presence of antigen (cystatin C) and increase the intensity of the scattered light. The amount of cystatin C in a sample is proportional to the increase in scattered light. The assay range is 0.195 to 7.330 mg/L (14.6 to 549.0 nmol/L); the reference range for young, healthy individuals is from 0.53 to 0.95 mg/L (40 to 71 nmol/L). The intra-assay coefficient of variation ranges from 2.0 to 2.8%, and the interassay coefficient of variation ranges from 2.3 to 3.1%.

Lipids and Lipoproteins

Lipid concentrations were measured using standard enzymatic methods, with LDL cholesterol calculated using the Friedewald formula (15). Lipoprotein concentrations were measured using NMR spectroscopy, as described in detail elsewhere (16–18). This method uses the characteristic signals broadcast by lipoprotein subclasses of different size as the basis for their quantification. Each subclass signal emanates from the total number of terminal methyl groups on the lipids contained within the particle core and in the surface shell. Lipoprotein particles were classified as HDL (7.3 to 13.0 nm), LDL (18.0 to 27.0 nm), or VLDL (>27 nm), with LDL subclassified as small LDL (18.0 to 21.2 nm), large LDL (21.2 to 23.0 nm), or intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL; 23.0 to 27.0 nm), consistent with previous studies (17–19). Average lipoprotein particle sizes were calculated from the concentrations of lipoprotein subclasses and the diameters assigned to each subclass. For categorical analyses, abnormal lipid concentrations were defined using established clinical thresholds: Elevated triglyceride ≥150 mg/dl, elevated LDL cholesterol ≥160 mg/dl, and low HDL cholesterol <50 mg/dl (women) or <40 mg/dl (men) (20). Because established thresholds do not exist for NMR lipoproteins, we arbitrarily used the gender-specific 75th percentile to define abnormal for NMR particle types of interest: Elevated small LDL particles ≥1035 nmol/L (women) or ≥1286 nmol/L (men) and elevated IDL particles ≥29.7 nmol/L (women) or ≥32.9 nmol/L (men).

Covariates

Race/ethnicity was self-classified by participants as white, Chinese, black, or Hispanic. Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl or use of diabetic medications (insulin, sulfonylureas, biguanides, thiazolidinediones, or α-glucosidase inhibitors), and impaired fasting glucose was defined as a fasting blood glucose ≥110 mg/dl in the absence of diabetes (21). BP was categorized as hypertension, prehypertension, or normal (22). Hypertension was defined as use of antihypertensive agents, systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 mmHg, or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mmHg; and prehypertension was defined as SBP ≥120 mmHg or DBP ≥80 mmHg in the absence of hypertension (22). Urine was collected from single voided specimens, with urine albumin concentration measured by nephelometry and urine creatinine concentration measured using the Jaffe reaction. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) was expressed in units of mg/g and log-transformed for all analyses. Serum creatinine was measured using a colorimetric method by a Kodak Ektachem 700 Analyzer (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and was standardized to Cleveland Clinic values using indirect calibration. eGFR was calculated from standardized serum creatinine using the abbreviated MDRD formula (23).

Statistical Analyses

Spearman rank-sum correlation was used to assess associations of cystatin C with other measures of kidney disease (eGFR and urine ACR) and associations of small LDL particle concentration with concentrations of other lipids and lipoproteins. Linear regression models examined the associations of cystatin C (independent variable) with lipid and lipoprotein concentrations (dependent variables) adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, fasting glucose status, BP, smoking, medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, β blockers, hydrochlorothiazide, estrogens [excluding topical preparations], and progesterones), body mass index (BMI), and urine ACR. We included interaction terms for gender with age, BMI, and urine ACR on the basis of previous literature reporting that gender modifies the relationships of these covariates with lipids levels (18,19). Quadratic terms were added for age and BMI because they significantly improved model fit (P < 0.05 by likelihood ratio test). When testing trend (for unadjusted or adjusted results), linear regression models used an ordinal variable for cystatin C quintile. Poisson regression was used to assess associations of cystatin C with lipid abnormalities, evaluated dichotomously. Poisson regression yields unbiased estimates of relative risk when outcomes are common, whereas logistic regression can lead to biased results in this setting (24). We tested whether age, gender, race/ethnicity, fasting glucose status, and the metabolic syndrome (20) modified the association of cystatin C with small LDL particle concentration using interaction terms. Effect modification was considered possible when the likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without cystatin C*covariate interaction terms yielded a significance value <0.1. Categorical and effect modification analyses evaluated cystatin C as a continuous variable scaled to 0.2 mg/L, approximately its interquartile range. Locally weighted regression and spline models suggested that the relationship of cystatin C with small LDL particle concentration was indeed linear.

Results

Greater serum cystatin C concentrations were associated with older age, male gender, impaired fasting glucose, higher BP, smoking, more frequent use of antihypertensive medications, less frequent use of estrogens and progesterones, and greater BMI (Table 1). Participants with greater cystatin C concentrations were more likely to be white and less likely to be Chinese. Serum cystatin C concentration was moderately correlated with eGFR (r = −0.43) and weakly correlated with urine ACR (r = 0.05). Small LDL particle concentration that was measured using NMR correlated moderately with concentrations of triglyceride (r = 0.58) and HDL cholesterol (r = −0.65) that were measured using conventional methods.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by quintile of serum cystatin Ca

| Characteristic | Cystatin C Quintile

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | |

| n | 993 | 910 | 1155 | 970 | 1081 |

| Cystatin C (mg/L; range) | 0.07 to 0.72 | 0.73 to 0.79 | 0.80 to 0.87 | 0.88 to 0.96 | 0.97 to 2.32 |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 56 ± 9 | 58 ± 9 | 60 ± 9 | 63 ± 10 | 66 ± 10 |

| Gender (n [%]) | |||||

| male | 328 (33) | 415 (46) | 575 (50) | 524 (54) | 613 (57) |

| female | 665 (67) | 495 (54) | 580 (50) | 446 (46) | 468 (43) |

| Race/ethnicity (n [%]) | |||||

| white | 311 (31) | 325 (36) | 407 (35) | 354 (36) | 454 (42) |

| Chinese | 180 (18) | 129 (14) | 134 (12) | 99 (10) | 83 (8) |

| black | 294 (27) | 254 (28) | 325 (28) | 267 (28) | 301 (28) |

| Hispanic | 208 (21) | 202 (22) | 289 (25) | 250 (26) | 243 (22) |

| Fasting glucose status (n [%]) | |||||

| normal | 656 (66) | 588 (65) | 713 (62) | 563 (58) | 590 (55) |

| impaired | 206 (21) | 219 (24) | 324 (28) | 291 (30) | 346 (32) |

| diabetes | 131 (13) | 103 (11) | 118 (10) | 116 (12) | 145 (13) |

| BP status (n [%]) | |||||

| normal | 500 (50) | 389 (43) | 470 (41) | 437 (34) | 289 (27) |

| prehypertension | 206 (21) | 221 (24) | 266 (23) | 204 (21) | 233 (22) |

| hypertension | 287 (29) | 300 (33) | 419 (36) | 439 (45) | 559 (52) |

| Active smoking (n [%]) | 105 (11) | 119 (13) | 168 (15) | 142 (15) | 199 (17) |

| Medications (n [%]) | |||||

| ACEI/ARB | 96 (10) | 108 (12) | 141 (12) | 162 (17) | 211 (20) |

| β blocker | 51 (5) | 48 (5) | 72 (6) | 83 (9) | 127 (12) |

| hydrochlorothiazide | 46 (5) | 57 (6) | 96 (8) | 95 (10) | 159 (15) |

| estrogensb | 199 (30) | 168 (34) | 150 (26) | 97 (22) | 93 (20) |

| progesteronesb | 101 (15) | 80 (16) | 56 (10) | 36 (8) | 34 (7) |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 26.8 ± 5.1 | 27.2 ± 4.9 | 27.9 ± 5.2 | 29.1 ± 5.7 | 29.6 ± 5.9 |

| Urine ACR (mg/g; median [IQR]) | 5.1 (3.4 to 10.0) | 4.8 (3.1 to 8.8) | 4.8 (3.0 to 8.5) | 5.0 (3.6 to 10.0) | 6.1 (3.6 to 14.1) |

| MDRD eGFR (ml/min; mean ± SD) | 92 ± 16 | 86 ± 14 | 83 ± 18 | 80 ± 13 | 75 ± 12 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated GFR; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Among women only.

In unadjusted analyses, cystatin C concentration was associated directly with triglyceride concentration and inversely with HDL concentration but not with LDL cholesterol concentration using conventional methods (Table 2). In examination of lipoproteins that were measured using NMR, greater cystatin C was associated with greater concentrations of VLDL, LDL, IDL, and small LDL particles and lesser concentrations of large LDL and HDL particles. Greater cystatin C was also associated with smaller mean LDL and HDL size.

Table 2.

Unadjusted lipid and lipoprotein measurements by quintile of serum cystatin Ca

| Parameter | Cystatin C Quintile

|

P (Trend) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | ||

| Standard lipids | ||||||

| total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 197 ± 34 | 198 ± 35 | 197 ± 34 | 196 ± 37 | 192 ± 37 | <0.001 |

| triglycerides (mg/dl) | 116 ± 93 | 127 ± 103 | 124 ± 82 | 134 ± 76 | 140 ± 81 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 118 ± 31 | 121 ± 31 | 121 ± 30 | 120 ± 32 | 117 ± 32 | 0.208 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 56 ± 16 | 52 ± 15 | 51 ± 15 | 49 ± 13 | 47 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| NMR particle number | ||||||

| VLDL (nmol/ml) | 65 ± 38 | 73 ± 42 | 72 ± 37 | 78 ± 40 | 78 ± 39 | <0.001 |

| LDL (nmol/ml) | 1270 ± 350 | 1330 ± 380 | 1330 ± 378 | 1340 ± 384 | 1330 ± 370 | 0.001 |

| IDL (nmol/ml) | 16 ± 23 | 20 ± 26 | 19 ± 23 | 21 ± 24 | 23 ± 24 | <0.001 |

| large LDL (nmol/ml) | 438 ± 205 | 420 ± 219 | 406 ± 200 | 395 ± 200 | 378 ± 207 | <0.001 |

| small LDL (nmol/ml) | 817 ± 432 | 889 ± 470 | 910 ± 457 | 927 ± 337 | 929 ± 442 | <0.001 |

| HDL (μ mol/ml) | 33 ± 6 | 31 ± 6 | 31 ± 6 | 30 ± 5 | 30 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| NMR particle size | ||||||

| VLDL (nm) | 51.5 ± 9.8 | 51.0 ± 10.1 | 50.9 ± 8.5 | 50.9 ± 8.4 | 51.6 ± 8.6 | 0.958 |

| LDL (nm) | 21.0 ± 0.8 | 20.9 ± 0.8 | 20.8 ± 0.8 | 20.8 ± 0.7 | 20.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| HDL (nm) | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

Data are means ± SD. IDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

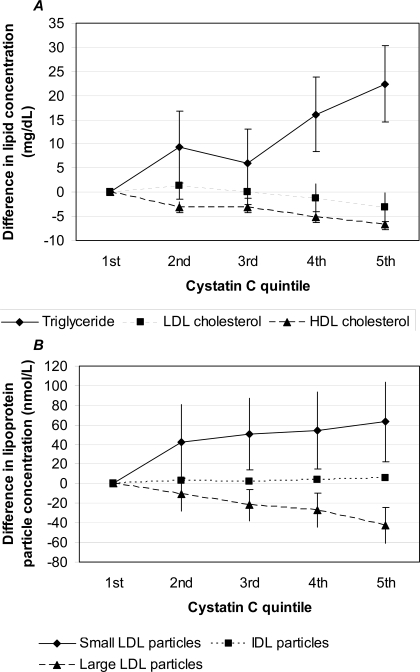

In adjusted analyses, greater cystatin C was associated with progressively greater triglyceride and lesser HDL cholesterol concentrations (each P < 0.001; Figure 1A). In a comparison of the fifth with the first cystatin C quintile, triglyceride concentration was on average 22 mg/dl higher (95% confidence interval [CI] 14 to 30) and HDL cholesterol concentration was 7 mg/dl lower (95% CI −8 to −5). Cystatin C was only weakly and not monotonically associated with LDL cholesterol that was measured using conventional methods (Figure 1A); however, when LDL particle subclasses were examined in more detail using NMR, greater cystatin C was associated with greater concentrations of small LDL and IDL particles and lesser large LDL particle concentration (each P < 0.001; Figure 1B). In a comparison of the fifth with the first cystatin C quintile, small LDL particle concentration was on average 63 nmol/L higher (95% CI 23 to 104) and IDL particle concentration was 6 mg/dl higher (95% CI 4 to 8). Cystatin C was also directly associated with VLDL particle concentration and inversely associated with HDL particle concentration and mean LDL and HDL particle sizes in adjusted analyses (each P < 0.001; data not shown). When 23 women and 37 men were excluded for triglyceride concentration ≥400 mg/dl, results for LDL cholesterol did not change. Results did not differ using continuous terms for BP or fasting glucose.

Figure 1.

Mean differences in lipid concentrations (conventional measurement methods; A) and LDL particle subclass concentrations (measured using nuclear magnetic resonance [NMR]; B) by quintile of cystatin C, compared with the first quintile, adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose status, BP status, smoking, medications, body mass index (BMI), and urine albumin-to-creatinine (ACR) ratio. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CI) and are contained within each data point for intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL). P < 0.001 (trend) for triglyceride, HDL cholesterol, and each LDL subclass; P = 0.013 (trend) for LDL cholesterol.

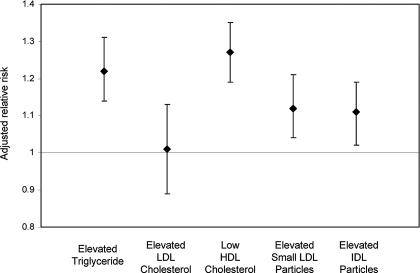

In analyses of abnormal lipid concentrations as dichotomous outcomes, greater cystatin C concentration was associated with increased prevalences of elevated triglyceride, low HDL cholesterol, elevated small LDL particles (NMR), and elevated IDL particles (NMR) but not with elevated LDL cholesterol that was measured using conventional methods (Table 3). Each 0.2-mg/dl increase in cystatin C was associated with fully adjusted relative risks of 1.22 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.31) for elevated triglyceride, 1.01 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.13) for elevated LDL cholesterol, 1.27 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.35) for low HDL, 1.12 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.21) for elevated small LDL particles, and 1.11 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.19) for elevated IDL particles (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Prevalence of abnormal lipid and lipoprotein concentrations by quintile of cystatin Ca

| Parameter | Cystatin C Quintile (n [%])

|

P (Trend) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | ||

| Elevated triglyceride | 191 (19) | 250 (27) | 295 (26) | 306 (32) | 387 (36) | <0.001 |

| Elevated LDL cholesterol | 92 (9) | 105 (12) | 129 (11) | 111 (11) | 126 (12) | 0.129 |

| Low HDL cholesterol | 276 (28) | 302 (33) | 373 (32) | 384 (40) | 499 (46) | <0.001 |

| Elevated small LDL particles | 198 (20) | 233 (26) | 303 (26) | 254 (26) | 290 (27) | 0.001 |

| Elevated IDL particles | 202 (20) | 225 (25) | 292 (25) | 252 (26) | 306 (28) | <0.001 |

Elevated triglyceride = triglyceride ≥150 mg/dl; elevated LDL cholesterol = LDL ≥160 mg/dl; low HDL cholesterol = HDL <50 mg/dl (women) or <40 mg/dl (men); elevated small LDL particles = small LDL particles (NMR) ≥1035 nmol/L (women) or ≥1286 nmol/L (men); elevated IDL particles = IDL particles (NMR) ≥29.7 nmol/L (women) or ≥32.9 nmol/L (men).

Figure 2.

Relative risk for abnormal lipid/lipoprotein concentrations associated with 0.2-mg/L greater serum cystatin C, adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose status, BP status, smoking, medications, BMI, and urine ACR. Elevated triglyceride = triglyceride ≥150 mg/dl; elevated LDL cholesterol = LDL cholesterol ≥160 mg/dl; low HDL cholesterol = HDL <50 mg/dl (women) or <40 mg/dl (men); elevated small LDL particles = small LDL particles (NMR) ≥1035 nmol/L (women) or ≥1286 nmol/L (men); elevated IDL particles = IDL particles (NMR) ≥29.7 nmol/L (women) or ≥32.9 nmol/L (men). Error bars represent 95% CI.

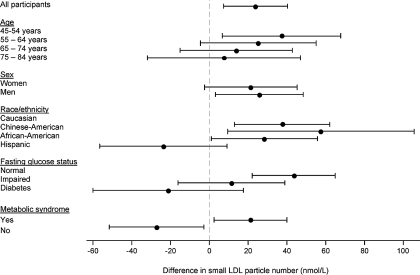

On average, each 0.2-mg/L greater cystatin C concentration was associated with a 24-nmol/L greater concentration of small LDL particles (95% CI 7 to 40 nmol/L) in multivariable adjusted analyses (Figure 3). There was a suggestion that this association was stronger with younger age, but this interaction was NS (P = 0.595). No effect modification by gender was observed (P = 0.780). The association of cystatin C with small LDL particle concentration tended to be of smaller magnitude among Hispanic participants and with worsened fasting glucose status or the metabolic syndrome (P = 0.007 for interaction for each of fasting glucose status and race/ethnicity; P < 0.001 for the metabolic syndrome). Similar interactions were observed for VLDL particles, LDL particles (all sizes), IDL particles, and LDL and HDL sizes, with reduced magnitudes of association observed for Hispanic participants with worse fasting glucose status or the metabolic syndrome (P < 0.1 for each interaction).

Figure 3.

Difference in small LDL particle number associated with 0.2-mg/L greater serum cystatin C, by subgroup, adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose status, BP status, smoking, medications, BMI, and urine ACR. Error bars represent 95% CI. Interaction P = 0.007 for each of fasting glucose status and race/ethnicity; interaction P < 0.001 for metabolic syndrome (NS for age and gender).

Discussion

Greater serum cystatin C was associated with unfavorable lipid and lipoprotein abnormalities among a diverse, community-based population with eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Lipid abnormalities that were observed using conventional measurements included modestly greater triglyceride and lesser HDL cholesterol concentrations. Cystatin C was not associated with elevated LDL cholesterol that was measured using conventional methods, but abnormalities in LDL particle distribution (greater concentrations of small LDL and IDL particles and a smaller mean LDL particle size) were observed using NMR. Associations were present across the full range of cystatin C and persisted after adjustment for potential confounders.

There are three main implications of these findings. First, atherogenic lipoprotein abnormalities are present with milder degrees of renal impairment than previously recognized. Second, important abnormalities in the distribution of LDL particles may not be appreciated in the setting of mildly impaired kidney function using conventional lipid measurements. Third, it is possible that lipoprotein abnormalities in early kidney disease may contribute to increased cardiovascular risk. In particular, greater concentrations of small LDL and IDL particles have been associated with progression of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular events independent of conventional lipid measurements (25–30). Compared with larger LDL particles, small LDL particles penetrate the arterial wall more easily, bind more avidly to extracellular matrix proteoglycans, and are more susceptible to oxidation and more resistant to clearing from the plasma (31–34).

The associations of reduced kidney function with conventional lipid measurements described here extend findings from previous community-based studies that assessed more advanced impairment of kidney function. Specifically, GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, estimated from serum creatinine, was associated with greater triglyceride and lesser HDL cholesterol levels but not elevated LDL cholesterol that was measured using conventional methods, in the Third National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES III), the Framingham offspring cohort, and the Cardiovascular Health Study (5–8,35). Using NMR, we additionally observed a shift in LDL distribution to small particles with an accumulation of IDL particles. This abnormal pattern of LDL distribution has been described among people with ESRD and may be present in moderate to severe CKD (stages 3 to 5) (36–40). Taken together, our results suggest that the lipoprotein abnormalities that are observed in advanced CKD and ESRD occur very early in the process of impaired kidney function.

It is possible that impaired kidney function leads to abnormal lipoprotein metabolism. In hemodialysis patients, activities of lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase are reduced, cholesterol ester transfer protein activity is increased, and levels of apolipoproteins (e.g., apoC-II, apoC-III, apo-E, apo-AI, apo-AII) are altered (4,36,41). It has been suggested that uremia causes these changes, either directly or through related metabolic processes such as inflammation, which lead to decreased metabolism of triglyceride-rich VLDL particles by adipose tissue, decreased clearance of IDL remnants by the liver, and metabolism of LDL to small, dense particles. The function of lipoprotein-modifying lipases has not been described in the setting of mild to moderate impairment of kidney function, but patterns of abnormalities presented here and elsewhere (38,39) suggest that similar defects may be present.

It is also possible that lipoprotein abnormalities lead to impaired kidney function. In cohort studies, lipid abnormalities have been associated with the incidence and progression of CKD (42–44). Moreover, lipid-lowering therapy has been associated with a modest decline in rate of CKD progression in clinical trials (45–47). Elevated triglyceride levels and diminished HDL levels have been most strongly associated with poor renal outcomes (42–44). Because small LDL particle concentration correlated directly with triglyceride and inversely with HDL cholesterol concentrations in our study and others and because small LDL particles are thought to be particularly atherogenic, our results raise the question of whether small LDL particles adversely affect kidney function. Whether atherogenic small LDL particles lead to increased damage in the renal endothelium or mesangium, relative to larger LDL particles, has not been described. Similarly, whether small LDL particles per se are associated with progression of kidney disease has not been reported.

The strengths of this study include external validity derived from the large, diverse, community-based population; the use of novel and sensitive measurements of kidney function and lipoprotein distribution; and the availability of detailed covariate information to minimize the potential impact of confounding. Three covariates merit specific comment. First, associations of cystatin C with lipids and lipoproteins were independent of urine albumin excretion, for which adjustment has generally not been made in previous studies. Second, many associations seemed to be weaker among participants with diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, or the metabolic syndrome. This may be a chance finding as a result of multiple testing of interactions; alternatively, other metabolic abnormalities may supersede the influence of impaired kidney function in this subpopulation. Third, associations also seemed to be weaker among participants who classified themselves as Hispanic. We are aware neither of other studies that have evaluated whether race/ethnicity modifies the relationship of kidney function with lipid or lipoprotein levels nor of mechanistic explanations for this observation. This possible interaction may represent a type I error, and it requires validation in future studies.

The main weakness of this study is its cross-sectional design, prohibiting definition of temporal and causal relationships between kidney function and lipoproteins. In addition, this study did not assess clinical cardiovascular events. When data on cardiovascular events become available for the MESA cohort, we will be able to evaluate whether lipoprotein abnormalities mediate any association of cystatin C with cardiovascular events. In addition, although some studies report that serum levels of cystatin C more accurately detect mild decrements in renal function compared with creatinine, others do not (48,49). Thus, cystatin C is not universally considered as a reliable marker of renal function in the setting of mild renal impairment, and its usefulness in clinical practice for the assessment of renal function is still in question (48,50). Moreover, serum cystatin C may reflect factors other than GFR (50–52), such that residual confounding of the relationship of cystatin C with lipoprotein abnormalities by nonrenal factors is possible.

Conclusion

Unfavorable lipid and lipoprotein abnormalities are present early in the course of impaired kidney function, as detected by elevated serum cystatin C. These abnormalities include atherogenic changes in LDL distribution that are not directly observed with conventional lipid measurements. These abnormalities may contribute to kidney disease progression and/or cardiovascular disease.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant K12 HD049100 from the National Institutes of Health Roadmap/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95166 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

We thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlipak MG, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Fried LF, Newman AB, Stehman-Breen C, Seliger SL, Kestenbaum B, Psaty B, Tracy RP, Siscovick DS: Cystatin C and prognosis for cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in elderly persons without chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 145: 237–246, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritz E, Wanner C: Lipid changes and statins in chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 17[Suppl]: S226–S230, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaziri ND: Dyslipidemia of chronic renal failure: The nature, mechanisms, and potential consequences. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F262–F272, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Cushman M, Manolio TA, Peterson D, Stehman-Breen C, Bleyer A, Newman A, Siscovick D, Psaty B: Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: Comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. JAMA 293: 1737–1745, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Levy D, Fox CS: Cardiovascular disease risk factors in chronic kidney disease: Overall burden and rates of treatment and control. Arch Intern Med 166: 1884–1891, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muntner P, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Chen J, Whelton PK, He J: The prevalence of nontraditional risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 140: 9–17, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Muntner P, Hamm LL, Jones DW, Batuman V, Fonseca V, Whelton PK, He J: The metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease in U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med 140: 167–174, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman DJ, Thakkar H, Edwards RG, Wilkie M, White T, Grubb AO, Price CP: Serum cystatin C measured by automated immunoassay: A more sensitive marker of changes in GFR than serum creatinine. Kidney Int 47: 312–318, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coll E, Botey A, Alvarez L, Poch E, Quinto L, Saurina A, Vera M, Piera C, Darnell A: Serum cystatin C as a new marker for noninvasive estimation of glomerular filtration rate and as a marker for early renal impairment. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 29–34, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Riordan SE, Webb MC, Stowe HJ, Simpson DE, Kandarpa M, Coakley AJ, Newman DJ, Saunders JA, Lamb EJ: Cystatin C improves the detection of mild renal dysfunction in older patients. Ann Clin Biochem 40: 648–655, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O'Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 156: 871–881, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erlandsen EJ, Randers E, Kristensen JH: Evaluation of the Dade Behring N Latex Cystatin C assay on the Dade Behring Nephelometer II System. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 59: 1–8, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18: 499–502, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otvos JD: Measurement of lipoprotein subclass profiles by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Lab 48: 171–180, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mora S, Szklo M, Otvos JD, Greenland P, Psaty BM, Goff DC Jr, O'Leary DH, Saad MF, Tsai MY, Sharrett AR: LDL particle subclasses, LDL particle size, and carotid atherosclerosis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 192: 211–217, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman DS, Otvos JD, Jeyarajah EJ, Shalaurova I, Cupples LA, Parise H, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Schaefer EJ: Sex and age differences in lipoprotein subclasses measured by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: The Framingham Study. Clin Chem 50: 1189–1200, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Boer IH, Astor BC, Kramer H, Palmas W, Rudser K, Seliger SL, Shlipak MG, Siscovick DS, Tsai MY, Kestenbaum B: Mild elevations of urine albumin excretion are associated with atherogenic lipoprotein abnormalities in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis August 4, 2007. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Executive Summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285: 2486–2497, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Standards of medical care in diabetes—2006. Diabetes Care 29[Suppl 1]: S4–S42, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, Bethesda, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2004 [PubMed]

- 23.Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ: A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine [Abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: A0828, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP: Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 157: 940–943, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamarche B, Tchernof A, Moorjani S, Cantin B, Dagenais GR, Lupien PJ, Despres JP: Small, dense low-density lipoprotein particles as a predictor of the risk of ischemic heart disease in men: Prospective results from the Quebec Cardiovascular Study. Circulation 95: 69–75, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuller L, Arnold A, Tracy R, Otvos J, Burke G, Psaty B, Siscovick D, Freedman DS, Kronmal R: Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of lipoproteins and risk of coronary heart disease in the cardiovascular health study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 1175–1180, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krauss RM, Lindgren FT, Williams PT, Kelsey SF, Brensike J, Vranizan K, Detre KM, Levy RI: Intermediate-density lipoproteins and progression of coronary artery disease in hypercholesterolaemic men. Lancet 2: 62–66, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blake GJ, Otvos JD, Rifai N, Ridker PM: Low-density lipoprotein particle concentration and size as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as predictors of cardiovascular disease in women. Circulation 106: 1930–1937, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Chang YF, Otvos J, Evans RW, Orchard TJ: Lipoprotein subclass measurements by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy improve the prediction of coronary artery disease in type 1 diabetes: A prospective report from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetologia 46: 674–682, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otvos JD, Collins D, Freedman DS, Shalaurova I, Schaefer EJ, McNamara JR, Bloomfield HE, Robins SJ: Low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein particle subclasses predict coronary events and are favorably changed by gemfibrozil therapy in the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Circulation 113: 1556–1563, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjornheden T, Babyi A, Bondjers G, Wiklund O: Accumulation of lipoprotein fractions and subfractions in the arterial wall, determined in an in vitro perfusion system. Atherosclerosis 123: 43–56, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anber V, Millar JS, McConnell M, Shepherd J, Packard CJ: Interaction of very-low-density, intermediate-density, and low-density lipoproteins with human arterial wall proteoglycans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 2507–2514, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tribble DL, Holl LG, Wood PD, Krauss RM: Variations in oxidative susceptibility among six low density lipoprotein subfractions of differing density and particle size. Atherosclerosis 93: 189–199, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Packard CJ, Shepherd J: Lipoprotein heterogeneity and apolipoprotein B metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 3542–3556, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verhave JC, Hillege HL, Burgerhof JG, Gansevoort RT, de Zeeuw D, de Jong PE: The association between atherosclerotic risk factors and renal function in the general population. Kidney Int 67: 1967–1973, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joven J, Vilella E, Ahmad S, Cheung MC, Brunzell JD: Lipoprotein heterogeneity in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 43: 410–418, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attman PO, Alaupovic P, Tavella M, Knight-Gibson C: Abnormal lipid and apolipoprotein composition of major lipoprotein density classes in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 63–69, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Attman PO, Samuelsson O, Alaupovic P: Lipoprotein metabolism and renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 21: 573–592, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samuelsson O, Attman PO, Knight-Gibson C, Kron B, Larsson R, Mulec H, Weiss L, Alaupovic P: Lipoprotein abnormalities without hyperlipidaemia in moderate renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 9: 1580–1585, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajman I, Harper L, McPake D, Kendall MJ, Wheeler DC: Low-density lipoprotein subfraction profiles in chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 2281–2287, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg AP, Applebaum-Bowden DM, Bierman EL, Hazzard WR, Haas LB, Sherrard DJ, Brunzell JD, Huttunen JK, Ehnholm C, Nikkila EA: Increase in lipoprotein lipase during clofibrate treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in patients on hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 301: 1073–1076, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muntner P, Coresh J, Smith JC, Eckfeldt J, Klag MJ: Plasma lipids and risk of developing renal dysfunction: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Kidney Int 58: 293–301, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaeffner ES, Kurth T, Curhan GC, Glynn RJ, Rexrode KM, Baigent C, Buring JE, Gaziano JM: Cholesterol and the risk of renal dysfunction in apparently healthy men. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2084–2091, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manttari M, Tiula E, Alikoski T, Manninen V: Effects of hypertension and dyslipidemia on the decline in renal function. Hypertension 26: 670–675, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tonelli M, Isles C, Craven T, Tonkin A, Pfeffer MA, Shepherd J, Sacks FM, Furberg C, Cobbe SM, Simes J, West M, Packard C, Curhan GC: Effect of pravastatin on rate of kidney function loss in people with or at risk for coronary disease. Circulation 112: 171–178, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tonelli M, Moye L, Sacks FM, Cole T, Curhan GC: Effect of pravastatin on loss of renal function in people with moderate chronic renal insufficiency and cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1605–1613, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fried LF, Orchard TJ, Kasiske BL: Effect of lipid reduction on the progression of renal disease: A meta-analysis. Kidney Int 59: 260–269, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madero M, Sarnak MJ, Stevens LA: Serum cystatin C as a marker of glomerular filtration rate. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 610–616, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delanaye P, Nellessen E, Cavalier E, Depas G, Grosch S, Defraigne JO, Chapelle JP, Krzesinski JM, Lancellotti P: Is cystatin C useful for the detection and the estimation of low glomerular filtration rate in heart transplant patients? Transplantation 83: 641–644, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Bergert J, Larson TS: Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin C among different clinical presentations. Kidney Int 69: 399–405, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macdonald J, Marcora S, Jibani M, Roberts G, Kumwenda M, Glover R, Barron J, Lemmey A: GFR estimation using cystatin C is not independent of body composition. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 712–719, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knight EL, Verhave JC, Spiegelman D, Hillege HL, de Zeeuw D, Curhan GC, de Jong PE: Factors influencing serum cystatin C levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int 65: 1416–1421, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]