Abstract

Background and objectives: Volume control is a key component of treatment of hemodialysis patients. The role of pedal edema as a marker of volume is unknown. The objective of this study was to determine factors that are associated with edema.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A cross-sectional study of asymptomatic hemodialysis patients (n = 146) in four university-affiliated hemodialysis units was conducted. Echocardiographic variables, blood volume monitoring, plasma volume markers (plasma renin and aldosterone and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide), and inflammation markers (C-reactive protein and IL-6) were measured as exposures, and edema was measured as outcome.

Results: In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, age, body mass index, and left ventricular hypertrophy were independent determinants of edema. Compared with patients with normal or low weight, overweight patients had odds ratio for edema of 5.7 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0 to 31.8), and obese patients of 44.8 (95% CI 9.0 to 223). Patients in the top quartile of left ventricular mass index and normal to low weight had odds ratio of edema of 7.7 (95% CI 2.3 −25.9), those who were overweight of 43.5 (95% CI 3.9 to 479.8), and those who were obese of 344.8 (95% CI 33.8 to 3515). Inferior vena cava diameter, blood volume monitoring, plasma volume markers, and inflammation markers were not determinants of edema.

Conclusions: Pedal edema correlates with cardiovascular risk factors such as age, body mass index, and left ventricular mass but does not reflect volume in hemodialysis patients.

Chronic kidney disease has emerged as a public health problem of substantial proportions, and the number of patients who require renal replacement therapy has been growing over the years (1). The mortality rate of patients with ESRD remains dismal, and a large part of this mortality is due to cardiovascular disease (2). In dialysis units, where volume control is achieved with long-duration dialysis, low cardiovascular mortality rates are seen, leading to the hypothesis that volume control may translate into better outcomes (3–5).

Assessment of volume state is an important component of the day-to-day treatment of hemodialysis (HD) patients (6). There is no single test that can diagnose or rule out volume overload (7,8). Physical examination findings such as pedal edema, elevated jugular venous pressure, hepatojugular reflex, basilar rales, and presence of left ventricular fourth heart sounds are commonly used to diagnose hypervolemia. The presence or absence of pitting pedal edema is perhaps the simplest physical sign to elicit; however, besides reflecting volume state, edema may be due to excess vascular permeability, stasis, or vasodilator drugs including dihydropyridines. The utility of this simple physical sign as a marker of hypervolemia in HD patients is unknown. The importance of this knowledge is self-evident. If excess volume can be diagnosed simply by presence of edema, then reducing dry weight in edematous patients can be a simple expedient to improve hypertension and heart failure (9). Conversely, if this physical sign is of limited value, then better markers to assess volume status must be sought.

In this study, we explored the association of edema as a marker of hypervolemia in HD patients. To test this hypothesis, we measured biochemical and echocardiographic markers of volume, performed continuous blood volume monitoring, and measured inflammation markers in HD patients and sought the association of these measurements with pedal edema.

Concise Methods

Participants

A total of 150 long-term HD patients were recruited between September 2003 and February 2005. The sample was drawn from 355 patients who were on thrice-weekly HD from four dialysis units affiliated with Indiana University; 48% were women, 36% had diabetes; and 72% were black. Four patients did not have evaluation for pedal edema and were excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Indiana University and Research and Development Committee of the Roudebush VA Medical Center (Indianapolis, IN), and all patients gave written informed consent.

The characteristics of this cohort have been previously reported and are briefly recapitulated next (10). The inclusion criteria were age >18 yr, on long-term HD for ≥3 mo, compliance with HD treatments as defined by fewer than two missed dialysis sessions per month, medically stable in the opinion of the investigator, and willingness to give informed consent. The exclusion criteria were active drug abuse, chronic atrial fibrillation, body mass index (BMI) ≥40 kg/m2, inability to learn or perform home BP monitoring, expected survival <6 mo, active cancer or known HIV positivity, and recent (<2 wk) change in antihypertensive drugs or dry weight.

Pedal edema was evaluated during dialysis by a physician who was not aware of the other measurements. Pressure was applied over the pretibial region, and when an indentation was visible, it was recorded as edema. We did not grade the edema because the interpretation of the grade is more subjective and to be reliable would need several observers. We also did not analyze the relationship of other physical signs of volume overload, such as displacement of the left ventricular apex, basilar rales, or elevated jugular venous pressure for the same reason. Furthermore, we did not elicit edema in places other than the pretibial region and did not record the presence of venous insufficiency.

Measurements

Blood was drawn in EDTA-containing tubes, and plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Biomarkers

All laboratory measurements were done before dialysis, and a specimen was obtained from the patient's arteriovenous access or tunneled dialysis catheter for HD. N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was measured using the Elecsys proBNP immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). IL-6 was assayed in plasma using a sandwich ELISA (Quantikine kit for Human IL-6 Immunoassay; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The correlation coefficient for standards was >0.99 and the lowest detectable limit was 0.039 pg/ml in undiluted plasma. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 7.8%, and the interassay coefficient of variation was 7.2%. C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured by Cobas Integra 400 autoanalyzer using a particle-enhanced turbidimetric assay (Cobas Integra C-Reactive Protein Latex; Roche Diagnostics). The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 1.8% and the interassay coefficient of variation was 2.9% at a mean level of 0.62 mg/dl CRP. Plasma renin activity was measured with a Clinical Assays GammaCoat RIA kit (Diasorin, Stillwater, MN). Plasma aldosterone concentration was measured by RIA with antiserum from Diagnostic Products Corp. (Los Angeles, CA).

Home BP Monitoring

Home BP monitoring was performed over 1 wk using a validated self-inflating automatic oscillometric device (HEM 705 CPl Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, IL) (10,11). Predialysis and postdialysis BP were obtained without any specified technique over 2 wk and averaged separately.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional guided M-mode echocardiograms were performed by one technician immediately after a midweek HD session with a digital cardiac ultrasound machine (Cypress Acuson, Siemens Medical, Malvern, PA) as reported previously (11). Left ventricular mass (LVM) was calculated using these measurements and corrected for height2.7 measured in meters because it corrects for the effects of obesity and correlates better with long-term outcomes in dialysis patients (12). Using apical four- and two-chamber views, ejection fraction was calculated by the Simpson biplane method, which, because of technically limited images, could be measured in only 126 echocardiograms.

Inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter was measured at the end of dialysis at the time of echocardiography at the level just below the diaphragm in the hepatic segment by two-dimensionally guided M-mode echocardiography. IVC diameter was measured just before the P wave of the electrocardiogram during end expiration and end inspiration, while avoiding Valsalva-like maneuvers. Collapsibility index was calculated as (maximal diameter on expiration − minimal diameter on deep inspiration)/maximal diameter on expiration × 100.

Hepatic vein Doppler signals were recorded in systole and diastole. The peak velocity at systole/(peak velocity at systole + peak velocity at diastole) was taken as hepatic vein systolic filling fraction. A regression equation 23 − 29 × hepatic vein systolic filling fraction was used to calculate the estimated right atrial pressure (13). The sensitivity and specificity for mean right atrial pressure of >8 mmHg for this equation is reported to be 86 and 92%, respectively.

Intradialytic Blood Volume Monitoring

Intradialytic blood volume monitoring was performed with the Crit-Line III-TQA (Hemametrics, Salt Lake City, UT). It incorporates photo-optical technology to measure noninvasively absolute hematocrit, percentage blood volume change, and continuous oxygen saturation. Measurements are made every 20 s throughout the duration of HD. We exported the machine stored time and hematocrit data to a relational database for further analysis.

The total amount of ultrafiltration (ml) was calculated for each patient on the basis of the dialysis machine reading. The total volume of ultrafiltration was divided by the dialysis time in hours to calculate the ultrafiltration rate (UFR). The UFR divided by postdialysis weight (kg) provided the UFR index: UFR index = UF (ml)/dialysis time (h)/postdialysis weight (kg).

The slope of relative blood volume (RBV) over time was calculated at percentage per hour using a straight line change model. RBV slope was divided by the UFR index to provide the volume index, which is suggested to be a marker of vascular refilling rate.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and analyzed using the Pearson χ2 test. Continuous variables were tested using a two-group t test. The biomarkers were not normally distributed and were tested using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A multivariable logistic regression model was created to test the independent role as determinants of edema. A stepwise model with backward elimination at P < 0.10 was used. The likelihood ratio test was used to test the significance of covariates that had a P value that was marginally significant. Similarly, an interaction effect of BMI and LVM was tested by the likelihood ratio in the nested model. The goodness of fit of the logistic model was evaluated by examination of the Hosmer Lemeshow statistic. Residual analysis was performed. Finally, the area under the curve and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the prediction model were created. All analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). The P values reported are two-sided and considered significant at <0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population according to the presence and absence of edema. The bivariate predictors of edema were age, gender, smoking, home systolic BP (SBP) and pulse pressure, predialysis and postdialysis pulse pressure, weight, BMI, LVM, predialysis plasma aldosterone, and CRP.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population by presence or absence of edemaa

| Clinical Characteristic | Overall | Edema | No Edema | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 146 | 34 (23) | 112 (77) | |

| Age (yr) | 55.2 ± 13.4 | 62.9 ± 12.6 | 52.9 ± 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Men | 93 (64) | 16 (47) | 77 (69) | 0.02 |

| Race | 0.60 | |||

| white | 13 (9) | 4 (12) | 9 (8) | |

| black | 131 (90) | 30 (88) | 101 (90) | |

| other | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | |

| Predialysis weight (kg) | 81.9 ± 19.6 | 92.9 ± 20.0 | 78.6 ± 18.3 | <0.001 |

| Postdialysis weight (kg) | 79.3 ± 19.0 | 90.1 ± 19.2 | 76.0 ± 17.8 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 ± 6.3 | 32.5 ± 5.5 | 25.6 ± 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Years of ESRD | 4.2 ± 3.8 | 3.7 ± 3.2 | 4.3 ± 4.0 | 0.43 |

| Never smokers | 45 (31) | 12 (35) | 33 (29) | 0.52 |

| Current smokers | 56 (38) | 5 (15) | 51 (46) | 0.001 |

| Cause of ESRD | 0.27 | |||

| diabetes | 50 (34) | 14 (41) | 36 (32) | |

| hypertension | 76 (52) | 18 (53) | 58 (52) | |

| other | 20 (14) | 2 (6) | 18 (16) | |

| Past cardiovascular disease | ||||

| coronary artery disease | 44 (30) | 13 (38) | 31 (28) | 0.24 |

| cerebrovascular disease | 25 (17) | 8 (24) | 17 (15) | 0.26 |

| peripheral vascular disease | 21 (14) | 5 (15) | 16 (14) | 0.95 |

| Antihypertensive medications | ||||

| direct vasodilators | 18 (12) | 3 (9) | 15 (13) | 0.48 |

| dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers | 52 (36) | 12 (35) | 40 (36) | 0.96 |

| Mean home BP (mmHg) | ||||

| systolic | 139.6 ± 22.3 | 146.6 ± 24.0 | 137.4 ± 21.4 | 0.04 |

| diastolic | 80.6 ± 13.3 | 77.7 ± 14.0 | 81.5 ± 13.0 | 0.15 |

| pulse pressure | 59.0 ± 16.4 | 68.9 ± 17.1 | 55.9 ± 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Mean predialysis unit BP (mmHg) | ||||

| systolic | 147.0 ± 21.4 | 150 ± 25.4 | 146 ± 20.1 | 0.35 |

| diastolic | 80.3 ± 13.1 | 76.8 ± 12.4 | 81.3 ± 13.2 | 0.08 |

| pulse pressure | 66.7 ± 13.9 | 73.2 ± 16.8 | 64.7 ± 12.4 | <0.01 |

| Clinical laboratory tests | ||||

| Kt/V | 1.6 ± 0.39 | 1.65 ± 0.46 | 1.60 ± 0.36 | 0.41 |

| albumin (g/dl) | 3.8 ± 0.36 | 3.8 ± 0.29 | 3.8 ± 0.38 | 0.91 |

| hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.5 ± 1.5 | 12.3 ± 1.4 | 12.5 ± 1.5 | 0.41 |

| creatinine (mg/dl) | 10.3 ± 2.7 | 9.6 ± 2.6 | 10.5 ± 2.7 | 0.09 |

| ferritin (ng/ml) | 676 ± 490 | 679 ± 361 | 675 ± 525 | 0.97 |

| calcium (mg/dl) | 9.2 ± 0.74 | 9.2 ± 0.83 | 9.2 ± 0.72 | 0.72 |

| phosphorus (mg/dl) | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 0.65 |

| Ca × P | 48.9 ± 16.2 | 49.8 ± 16.0 | 48.7 ± 16.3 | 0.72 |

| Echocardiographic markers | ||||

| LVM/height2.7 (g/m2.7) | 59.0 ± 16.6 | 69.9 ± 19.9 | 55.6 ± 14.0 | <0.001 |

| ejection fraction (%) | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.51 |

| IVC diameter (mm/m2) | 8.7 ± 3.7 | 8.5 ± 3.3 | 8.7 ± 3.8 | 0.8 |

| IVC collapsibility index (%) | 31.5 ± 17.9 | 27.2 ± 15.9 | 32.8 ± 18.3 | 0.13 |

| right atrial pressure (mmHg) | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 6.2 ± 3.1 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 0.89 |

| left atrial diameter (cm) | 4.31 ± 0.67 | 4.35 ± 0.61 | 4.30 ± 0.69 | 0.75 |

| pulmonary artery SBP (mmHg) | 43.9 ± 9.4 | 47.2 ± 1.6 | 43.0 ± 9.6 | 0.04 |

| elevated pulmonary artery SBP | 9 (8) | 2 (8) | 7 (8) | 0.96 |

| Circulating volume markers | ||||

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml) | 6165 ± 7907 | 4830 ± 6464 | 6570 ± 8279 | 0.25 |

| renin predialysis (ng/ml per h) | 2.24 ± 4.78 | 2.86 ± 4.77 | 2.05 ± 4.79 | 0.17 |

| renin postdialysis (ng/ml per h) | 2.53 ± 4.97 | 3.25 ± 5.48 | 2.32 ± 4.81 | 0.24 |

| aldosterone predialysis (ng/ml) | 17.2 ± 21.4 | 23.3 ± 30.1 | 15.4 ± 17.8 | 0.07 |

| aldosterone postdialysis (ng/ml) | 15.2 ± 25.7 | 16.2 ± 22.6 | 14.9 ± 26.7 | 0.22 |

| inflammation markers | ||||

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.98 ± 1.48 | 1.22 ± 1.61 | 0.90 ± 1.43 | 0.03 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 4.0 ± 6.8 | 3.9 ± 3.6 | 4.0 ± 7.5 | 0.12 |

| Blood volume monitoring markers | ||||

| RBV index (slope %/h) | −2.35 ± 1.48 | −2.27 ± 1.40 | −2.37 ± 1.50 | 0.73 |

| volume index (slope %/h per ml/kg per h UFR index) | −0.28 ± 0.18 | −0.31 ± 0.23 | −0.27 ± 0.16 | 0.18 |

| UFR index (ml/kg per h) | 8.4 ± 3.8 | 7.4 ± 3.1 | 8.7 ± 4.0 | 0.09 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). Continuous variables P values computed through two-group t test except for circulating volume and inflammation markers, for which Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was used. Categorical variables P values computed through Pearson χ 2. BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; IVC, inferior vena cava; LVM, left ventricular mass; RBV, relative blood volume; SBP, systolic BP; UFR, ultrafiltration rate.

To evaluate the relationship of BMI with edema further, we divided the BMI into categories according to the World Health Organization. None (zero of 10) of the underweight, 8% (four of 51) of normal-weight, 13% (five of 40) of overweight, and 56% (25 of 45) of obese patients had edema. Thus, overweight and obese HD patients were more likely to be edematous compared with underweight or normal-weight patients. The underweight and normal-weight categories were merged because they had similar risk for edema. The relationship of edema and LVM quartiles demonstrated that for the first three quartiles, the prevalence of edema was between 12 and 18%; however for the highest quartile (>68.8 g/m2.7), the prevalence of edema was 49% (17 of 35). Accordingly, we created two categories for LVM: Those in the highest quartile and those in the lower quartiles. Age, however, seemed to have a more linear relationship with edema. Edema was present in 17% (three of 18) of those who were younger than 40, 7% (two of 30) in those who were 40 to 50, 20% (10 of 50) in those who were 50 to 60, 36% (10 of 28) in those who were 60 to 70, and 45% (nine of 20) in those who were >70 yr of age. The highest quartile of home SBP had 36% (12 of 33) prevalence of edema compared with 18, 25, and 18% in the first three quartiles, respectively. The lowest quartile of home diastolic BP (DBP) had 34% (13 of 38) prevalence of edema compared with 24, 16, and 21% for the successive higher quartiles.

Table 2 shows the Spearman correlation coefficients for the bivariate predictors that were significant. BMI was correlated with gender, smoking, pulse pressure, LVM, plasma aldosterone, and CRP. Thus, it became important to assess the independent effects of markers other than BMI on edema.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between various markersa

| Parameter | Age | Men | BMI | Smoker | SBP | PP | LVM | Aldosterone | CRP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1 | ||||||||

| Men | −0.15 | 1 | |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.05 | −0.20b | 1 | ||||||

| Current smokers | −0.08 | 0.23b | −0.29c | 1 | |||||

| Home SBP (mmHg) | 0.11 | −0.13 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 1 | ||||

| Home PP (mmHg) | 0.38c | −0.18b | 0.17b | −0.13 | 0.81c | 1 | |||

| LVM/height2.7 (g/m2.7) | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.24d | 0.08 | 0.21c | 0.34c | 1 | ||

| Aldosterone predialysis | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.25d | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.17b | 0.13 | 1 | |

| CRP | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.19b | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.19b | 0.02 | 1 |

PP pulse pressure.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

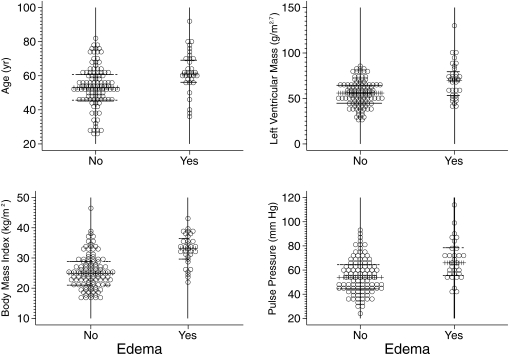

To account for the nonlinear relationship, we used the underweight plus normal-weight groups as the reference category to compare the odds ratio for edema in the overweight and obese categories of BMI. The fourth quartile of LVM and the continuous variables for age were modeled to arrive at the final model. Table 3 shows the multivariate logistic model, which shows that age, BMI, and LVM were the most important determinants of edema. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for this model was 0.91 (95% CI 0.85 to 0.96). Analysis of the data after removal of patients who were on vasodilators did not change the results meaningfully (data not shown). Figure 1 shows the dot plot demonstrating the distribution of the variables in the final logistic model.

Table 3.

OR for edema in relation to obesity and left ventricular hypertrophya

| BMI | LVM <68.8 g/m2.7

|

LVM ≥68.8 g/m2.7

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Underweight or normal (<25 kg/m2) | 1 | 7.7 | 2.3 to 25.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Overweight (25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2) | 5.7 | 1.0 to 31.8 | 0.049 | 43.5 | 3.9 to 479.8 | <0.01 |

| Obese (>30 kg/m2) | 44.8 | 9.0 to 223.0 | <0.001 | 344.8 | 33.8 to 3515.0 | <0.001 |

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) associated with BMI and left ventricular hypertrophy adjusted for age. Hosmer-Lemeshow χ 2 1.50 (P = 0.99).

Figure 1.

Dot plots of age, left ventricular mass, body mass index, and pulse pressure with home BP monitoring in relation to edema. The horizontal lines represent medians and the interquartile range.

To explore whether the home BP could be used as a surrogate for LVM, we selected the highest quartile of SBP (≥156 mmHg) as systolic hypertension and the lowest quartile of DBP (72 mmHg or less) as diastolic hypotension. We fitted a multivariable logistic model that contained the three categories of BMI, the two categories of SBP, the two categories of DBP, and age a continuous variables. The results of this model are shown in Table 4. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for this model was 0.89 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.96). The Akaike information criterion for model fit was 104.0 compared with 95.5 for the model in Table 3, suggesting slightly worse fit.

Table 4.

OR for edema in relation to obesity and systolic hypertensiona

| BMI | Home SBP <156 mmHg

|

Home SBP ≥156 mmHg

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Underweight or normal (<25 kg/m2) | 1 | 5.3 | 1.3 to 21.8 | 0.02 | ||

| Overweight (25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2) | 2.8 | 0.6 to 13.5 | 0.21 | 14.7 | 1.8 to 119.3 | 0.012 |

| Obese (>30 kg/m2) | 41.2 | 8.9 to 190.5 | <0.001 | 217.3 | 20.2 to 2234.6 | <0.001 |

OR (95% CI) associated with BMI and systolic hypertension assessed by home BP monitoring adjusted for age and diastolic BP. Hosmer-Lemeshow χ 2 6.64 (P = 0.58).

Discussion

We found that pedal edema in HD patients was associated with common cardiovascular risk factors such as older age, overweight or obesity, and left ventricular hypertrophy. Edema was not correlated to NT-proBNP, IVC diameter, collapse index, ejection fraction, right atrial pressure, left atrial diameter, or changes in RBV. The use of vasodilating drugs was also not associated with edema in HD patients. Finally, inflammation was not independently associated with edema in our patients.

The determination of volume state is admittedly difficult; therefore, we used a panel of markers that included biochemical parameters (renin, aldosterone, and NT-proBNP), RBV, and echocardiograms. None of these markers was correlated with edema. This suggests that edema may not be a marker of intravascular volume in stable long-term HD patients. In contrast, CRP was elevated in patients with edema. Although CRP was not independently linked to the presence of edema, it was correlated with obesity. Thus, obesity may be mediating some of the effects on edema through CRP.

The independent determinants of edema were BMI, age, and LVM. Gender was no longer a significant variable because 46% of the women were obese compared with 20% of the men. Home BP was no longer a significant determinant of edema because this variable was significantly correlated with LVM. In fact, the results shown in Table 4 suggest that hypertension and LVM are similarly related to edema. Likewise, CRP and predialysis aldosterone were correlated with BMI. There were fewer smokers among edematous patients. One reason for this could be that smokers were in general thinner, and this may have led to a spurious association. After accounting for obesity, smoking was no longer protective.

Why did edema fail to be a determinant of accepted markers of volume? Obesity was the most important determinant of edema in our patients. Reduced mobility and stasis may promote the formation of edema. Adipose tissue is being increasingly recognized as a metabolically active organ that can release adipokines that can influence vascular permeability (14,15). In fact, we found that BMI was linked to CRP (r = 0.19, P = 0.02) and predialysis aldosterone (r = 0.25, P = 0.002). Thus, adiposity may independently increase vascular permeability and cause edema. Another explanation for the constellation of signs and symptoms in our study could be sleep apnea, which is associated with obesity, hypertension, and elevated pulmonary artery pressure.

The presence of edema was an important observation in that it was associated with higher home SBP and lower DBP and, therefore, higher pulse pressure. It was also linked to higher LVM. These cardiovascular risk factors that were more common in edematous dialysis patients can be treated with the use of dietary and dialysate sodium restriction and antihypertensive drugs (16–18). Although edema does not predict an increased intravascular volume, it does signal the increased likelihood of presence of these risk factors, which can be identified and treated.

There are several limitations of our study. For example, we show that edema as an isolated physical sign has limited value in assessing volume state; however, a constellation of signs such as bibasilar rales or raised jugular venous pressure may increase the value of edema in diagnosing hypervolemia. Using multiple observers and repeated observations in the same patient may further increase the value of this important physical sign.

Conclusions

Edema is of limited value in diagnosing excess intravascular volume; however, detection of edema is of substantial importance because its presence is independently linked to left ventricular hypertrophy and indirectly to systolic hypertension and widened pulse pressure. To the extent that these factors are important in predicting mortality in dialysis patients, eliciting this simple bedside physical sign may improve our ability to identify and treat these cardiovascular risk factors.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 5RO1-NIDDK062030-05 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank the staff of the dialysis units at Dialysis Clinics, Inc., Clarian Health, and the Roudebush VA Medical Center and the faculty of the Division of Nephrology, who graciously allowed us to the study their patients.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 1–12, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung AK, Sarnak MJ, Yan G, Berkoben M, Heyka R, Kaufman A, Lewis J, Rocco M, Toto R, Windus D, Ornt D, Levey AS: Cardiac diseases in maintenance hemodialysis patients: Results of the HEMO Study. Kidney Int 65: 2380–2389, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saad E, Charra B, Raj DS: Hypertension control with daily dialysis. Semin Dial 17: 295–298, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charra B: Control of blood pressure in long slow hemodialysis. Blood Purif 12: 252–258, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charra B, Calemard E, Ruffet M, Chazot C, Terrat J-C, Vanel T, Laurent G: Survival as an index of adequacy of dialysis. Kidney Int 41: 1286–1291, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charra B: “Dry weight” in dialysis: The history of a concept. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 1882–1885, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaeger JQ, Mehta RL: Assessment of dry weight in hemodialysis: An overview. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 392–403, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishibe S, Peixoto AJ: Methods of assessment of volume status and intercompartmental fluid shifts in hemodialysis patients: Implications in clinical practice. Semin Dial 17: 37–43, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson J, Shah T, Nissenson AR: Role of sodium and volume in the pathogenesis of hypertension in hemodialysis. Semin Dial 17: 260–264, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ, Bishu K, Saha C: Home blood pressure monitoring improves the diagnosis of hypertension in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 69: 900–906, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal R, Brim NJ, Mahenthiran J, Andersen MJ, Saha C: Out-of-hemodialysis-unit blood pressure is a superior determinant of left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension 47: 62–68, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Giacone G, Cataliotti A, Seminara G, Stancanelli B, Malatino LS: Prognostic impact of the indexation of left ventricular mass in patients undergoing dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2768–2774, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagueh SF, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA: Relation of mean right atrial pressure to echocardiographic and Doppler parameters of right atrial and right ventricular function. Circulation 93: 1160–1169, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Axelsson J, Rashid QA, Suliman ME, Honda H, Pecoits-Filho R, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Cederholm T, Stenvinkel P: Truncal fat mass as a contributor to inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 1222–1229, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Festa A, D'Agostino R Jr, Williams K, Karter AJ, Mayer-Davis EJ, Tracy RP, Haffner SM: The relation of body fat mass and distribution to markers of chronic inflammation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25: 1407–1415, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flanigan M: Dialysate composition and hemodialysis hypertension. Semin Dial 17: 279–283, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad S: Dietary sodium restriction for hypertension in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 17: 284–287, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horl MP, Horl WH: Drug therapy for hypertension in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial 17: 288–294, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]