Abstract

Background and objectives: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species is the most common cause of peritoneal dialysis–related peritonitis; however, the optimal treatment strategy of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species peritonitis remains controversial.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: All of the coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species peritonitis in a dialysis unit from 1995 to 2006 were reviewed. During this period, there were 2037 episodes of peritonitis recorded; 232 episodes (11.4%) in 155 patients were caused by coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species.

Results: The overall primary response rate was 95.3%; the complete cure rate was 71.1%. Patients with a history of recent hospitalization or recent antibiotic therapy had a higher risk for developing methicillin-resistant strains. Episodes that were treated initially with cefazolin or vancomycin had similar primary response rate and complete cure rate. There were 33 (14.2%) episodes of relapse and 29 (12.5%) episodes of repeat peritonitis; 12 (60.6%) of the repeat episodes developed within 3 mo after completion of antibiotics. Relapse or repeat episodes had a significantly lower complete cure rate than the other episodes. For relapse or repeat episodes, treatment with effective antibiotics for 3 wk was associated with a significantly higher complete cure rate than the conventional 2-wk treatment.

Conclusions: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species peritonitis remains a common complication of peritoneal dialysis. Methicillin resistance is common, but the treatment outcome remains favorable when cefazolin is used as the first-line antibiotic. A 3-wk course of antibiotic can probably achieve a higher cure rate in relapse or repeat episodes.

Peritonitis is a serious complication of peritoneal dialysis (PD) and probably the most common cause of technique failure in PD (1–5). In the United States, 18% of the infection-related mortality in PD patients is the result of peritonitis (6). Although fewer than 4% of the peritonitis episodes resulted in death (7), peritonitis is a “contributing factor” in 16% of deaths of patients who are on PD (8). In Hong Kong, peritonitis is the direct cause of death in >16% of PD patients (9).

Gram-positive organisms remain the most common bacteriologic cause of PD-related peritonitis (1,5,10); coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species (CNSS) accounted for nearly half of all Gram-positive episodes (11,12), although it is less common a cause of mortality as compared with Gram-negative peritonitis (12). It is commonly believed that CNSS peritonitis is primarily due to touch contamination and is generally a mild form of peritonitis that responds readily to antibiotic therapy (13). Current guideline for the management of CNSS peritonitis by the Ad Hoc Advisory Committee on Peritonitis Management recommends single effective antibiotics therapy, for example, cefazolin or vancomycin, for 2 wk (13). In methicillin-sensitive organisms, cefazolin has been shown to have equivalent results to vancomycin (14,15) and is usually the agent preferred so that excessive use of vancomycin could be minimized (13); however, the optimal treatment strategy of CNSS peritonitis remains controversial. The current treatment recommendation by the Ad Hoc Advisory Committee was largely based on small studies and expert opinion (13). Many dialysis programs have a high rate of methicillin-resistant organisms (16–18). Using cefazolin as the first-line antibiotic for Gram-positive organisms may theoretically result in delaying the use of effective treatment, and vancomycin is often considered the only appropriate first-line coverage for Gram-positive organisms in centers with a high incidence of methicillin resistance (12,18). In this study, we reviewed the clinical course and therapeutic outcome of 232 consecutive episodes of CNSS peritonitis in a large unselected cohort of PD patients over 12 yr. We aimed to identify key factors that could improve the treatment outcome of this common complication of PD.

Concise Methods

All PD patients of our center gave written consent for reviewing their clinical data when they entered the dialysis program. All episodes of PD peritonitis in our unit from 1995 to 2006 were reviewed. The diagnosis of peritonitis was based on at least two of the following (19,20): (1) abdominal pain or cloudy peritoneal dialysis effluent (PDE); (2) leukocytosis in PDE (white blood cell count >100/ml); and (3) positive Gram stain or culture from PDE. Episodes with peritoneal eosinophilia but negative bacterial culture were excluded. Exit-site infection was diagnosed when there was purulent drainage, with or without erythema, from the exit site (21). In this review, relapse peritonitis was defined as an episode that occurred within 4 wk of completion of therapy of a previous episode with the same organism (or culture negative) (13). Recurrent peritonitis was defined as an episode that occurred within 4 wk of completion of therapy of a previous episode but with a different organism (13). Complete cure was defined as complete resolution of peritonitis by antibiotics alone without relapse or recurrence within 4 wk of completion of therapy. Repeat peritonitis was defined as an episode that occurred >4 wk after completion of therapy of a previous episode with the same organism (13).

In the 12-yr study period, 2037 episodes of peritonitis were recorded; 254 (12.5%) episodes were caused by CNSS. Twenty-two episodes were excluded from analysis because PDE culture showed mixed bacterial growth. The case records of the remaining 232 episodes in 155 patients were reviewed. The demographic characteristics, underlying medical conditions, previous peritonitis, recent antibiotic therapy, antibiotic regimen for the peritonitis episode, requirement of Tenckhoff catheter removal, and clinical outcome were examined.

Microbiological Investigations

Bacterial culture of PDE was performed by BacTAlert bottles (Organon Teknika Corp., Durham, NC). Species identification was performed by the API 20E identification system (BioMerieux, Marcy l'Etolie, France). We further reviewed the 99 consecutive episodes from 2000 to 2006 for which records on antibiotic sensitivity were available. Antibiotic sensitivity was determined by disc-diffusion method according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standard (22).

Clinical Management

Peritonitis episodes were treated with standard antibiotic protocol of our center at that time, which was changed systemically over time. Initial antibiotics for peritonitis were generally intraperitoneal administration of a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin, with or without intermittent vancomycin every 5 d, or cefazolin as continuous administration plus an aminoglycoside or ceftazidime (5). The dosages of vancomycin and cefazolin followed the contemporary guideline (13). During the review period, two clinical trials on monotherapy of peritonitis by cefepime and imipenem/cilastatin had been conducted in our center (23,24); 45 episodes in this review were therefore treated initially with a regimen other than cefazolin and vancomycin. Antibiotic regimens for individual patients were modified when culture results were available.

When the initial antibiotic was cefazolin and the PDE did not clear up on day 5 (or methicillin-resistant species was identified from PDE before day 5), the antibiotic was changed to vancomycin. Primary response was defined as resolution of abdominal pain, clearing of dialysate, and PDE neutrophil count <100/ml on day 10 with antibiotics alone. In general, patients received effective antibiotic for 14 d. In 32 (13.8%) episodes, the effective antibiotic was continued for a total of 21 d. The decision of a 3-wk course of treatment was judged clinically by an individual nephrologist, usually because of a slow initial clinical response, concomitant exit-site infection, or the episode's being a relapse or repeat one. When the PDE did not clear up after 5 d of effective antibiotics, the Tenckhoff catheter was removed irrespective of the in vitro sensitivity of the bacterial strain and effective antibiotic was continued for another 2 wk.

Tenckhoff catheters were removed and patients were put on temporary hemodialysis when peritonitis failed to resolve with antibiotics. Tenckhoff catheter reinsertion was attempted in all cases. In our locality, as described in our previous study (4), patients were switched to long-term hemodialysis only when attempts of Tenckhoff catheter reinsertion failed because of peritoneal adhesion or when there was ultrafiltration failure as a result of peritoneal sclerosis. All of the patients were followed for at least 3 mo after their treatment completed.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 10.0 for Windows software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). All data are expressed as means ± SD unless otherwise specified. Data were compared by χ2 test, Fisher exact test, and t test as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All probabilities were two-tailed.

Results

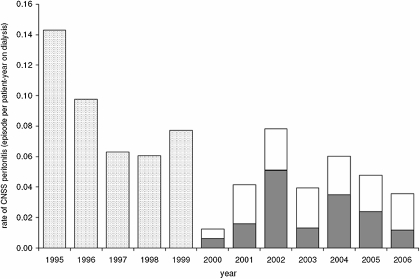

From 1995 to 2006, 2037 episodes of PD-related peritonitis were recorded in our unit. The overall peritonitis rate was 21.3 patient-months per episode. We reviewed 232 (11.4%) episodes of CNSS peritonitis in 155 patients. Of these, 111 patients had one episode, 22 patients had two episodes, and 22 patients had three or more episodes. The absolute rate of CNSS peritonitis was 0.064 episodes per patient-year of treatment. There was a substantial decline in the absolute incidence of CNSS peritonitis in the late 1990s (Figure 1); however, the proportion of PD-related peritonitis that was caused by CNSS remained static during the study period.

Figure 1.

Absolute peritonitis rate of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species (CNSS) peritonitis during the 12-yr study period. □, methicillin-sensitive strains; ▪, methicillin-resistant strains; □, from 1995 to 1999: total rate irrespective of sensitivity to methicillin.

The demographic and baseline clinical data of the 155 patients are summarized in Table 1. In 22 (9.5%) episodes, there was concomitant exit-site infection. It is important to note, however, that CNSS was isolated in only two episodes. The bacteriologic cause of exit-site infection is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 155 |

| Gender (M:F) | 92:63 |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 56.8 ± 13.9 |

| Duration of dialysis (mo; mean ± SD) | 34.8 ± 27.6 |

| Body height (m; mean ± SD) | 1.61 ± 0.10 |

| Body weight (kg; mean ± SD) | 59.9 ± 10.9 |

| Diagnosis (n [%]) | |

| glomerulonephritis | 53 (34.2) |

| diabetes | 42 (27.1) |

| hypertension | 8 (5.2) |

| polycystic | 6 (3.9) |

| obstruction | 10 (6.5) |

| others/unknown | 36 (23.2) |

| Major comorbidity (n [%]) | |

| coronary heart disease | 33 (21.3) |

| congestive heart failure | 38 (24.5) |

| peripheral vascular disease | 8 (5.2) |

| cerebrovascular disease | 28 (18.1) |

| dementia | 7 (4.5) |

| chronic pulmonary disease | 5 (3.2) |

| connective tissue disorder | 6 (3.9) |

| peptic ulcer disease | 12 (7.7) |

| mild liver disease | 22 (14.2) |

| diabetes | 11 (7.1) |

| hemiplegia | 28 (18.1) |

| diabetes with end-organ damage | 42 (27.1) |

| any tumor, leukemia, lymphoma | 7 (4.5) |

| moderate or severe liver disease | 7 (4.5) |

| metastatic solid tumor | 0 |

| AIDS | 0 |

| Charlson index score (mean ± SD) | 5.4 ± 2.3 |

Table 2.

Summary of bacterial species causing exit-site infectiona

| No. of cases | 22 |

| Organisms identified | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3b |

| CNSS | 2 |

| Escherichia coli or other Enterobacteriaceae | 4 |

| Pseudomonas species | 6 |

| polymicrobial | 4 |

| no growth | 3 |

CNSS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species.

None of them was methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Of the 232 episodes, 25 (10.8%) developed when the patient was hospitalized for other medical reasons. In another 37 (15.9%) episodes, the patient had had hospitalization within 30 d before the onset of CNSS peritonitis. There was a history of antibiotic therapy within 30 d before the onset of CNSS peritonitis in 91 (39.2%) episodes. Antibiotics were given in 34 (14.7%) cases for a recent peritonitis episode, in 17 (7.3%) cases for recent exit-site infection, and in 40 (17.2%) cases for unrelated medical reasons. In 12 (5.2%) cases, the patient received two or more antibiotics within 30 d before the onset of Staphylococcus aureus peritonitis.

Clinical Outcome

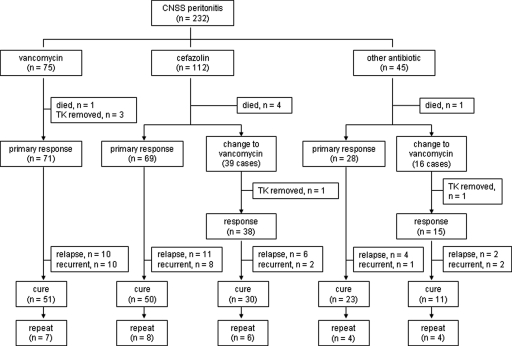

The overall primary response rate was 95.3%; the complete cure rate was 71.1%. The clinical outcome is summarized in Figure 2. Six (2.6%) patients died during the treatment of peritonitis (see Figure 1). Nonetheless, only one patient died of CNSS peritonitis per se; other causes of death were nosocomial pneumonia (two cases), myocardial infarction (two cases), and stroke (one case). Tenckhoff catheter removal was needed in five (2.2%) episodes; resumption of PD was possible in four patients after 3 to 4 wk of temporary hemodialysis.

Figure 2.

Summary of clinical outcome of CNSS peritonitis. TK, Tenckhoff catheter.

We then analyzed the predicting factor of treatment response. Patients with recent hospitalization had a lower primary response rate as compared with the others (88.5 versus 97.2%; P = 0.018), but the complete cure rate was similar. In contrast, patients with recent antibiotic exposure had a marginally lower complete cure rate as compared with the others (63.7 versus 75.9%; P = 0.054), but the primary response rate was similar. Episodes that were treated with cefazolin as the initial antibiotic had a similar primary response rate as those that were treated with vancomycin or other antibiotics from the beginning (95.5 versus 94.7 and 95.6%, respectively; overall χ2 test P = 0.9), and the complete cure rate was also similar (71.4 versus 68.0 and 75.6%, respectively; overall χ2 test P = 0.7). For the same patient who had more than one episode of CNSS peritonitis, subsequent episodes had a marginally lower primary response rate than the first episode (92.2 versus 100%; P = 0.085), but the complete cure rate was similar (62.3 versus 61.4%; P = 0.9). There was no difference in primary response rate (95.0 versus 96.9%; P = 0.9) or complete cure rate (70.5 versus 75.0%; P = 0.7) between episodes that were treated with 2 and 3 wk of antibiotics. Age, diabetic status, Charlson comorbidity score, and concomitant exit-site infection did not significantly affect the primary response rate or complete cure rate (data not shown).

Methicillin Resistance

As described in the Materials and Methods section, we performed further subgroup analysis on the 99 consecutive episodes from 2000 to 2006 for which records on antibiotic sensitivity were available. Forty-nine (49.5%) episodes were caused by methicillin-resistant strains. The incidence of methicillin resistance remained static over the years (Figure 1). Episodes that were caused by methicillin-resistant strains had similar primary response rate (91.8 versus 98.0%; P = 0.2) and complete cure rate (65.3 versus 76.0%; P = 0.3) as compared with those that were caused by methicillin-sensitive strains. Even when the subgroup cases that were treated with cefazolin as the first-line antibiotic were analyzed, episodes that were caused by methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive bacteria had similar primary response rate (90.0 versus 97.7%; P = 0.2) and complete cure rate (65.0 versus 72.7%; P = 0.5).

We further analyzed the risk factors of isolating methicillin-resistant strains from the patient. Patients with a history of recent hospitalization had a higher risk for isolation of methicillin-resistant strains than the others (66.7 versus 42.0%; P = 0.021). A history of recent antibiotic therapy was also associated with a higher risk (69.7 versus 39.46%; P = 0.04). Patients who developed CNSS peritonitis during hospitalization also had a marginally higher risk for isolation of methicillin-resistant strains than outpatients (62.5 versus 47.0%; P = 0.2), but the result was not statistically significant because the absolute number of in-patient peritonitis was small (16 episodes). Age, diabetic status, Charlson comorbidity score, and concomitant exit-site infection did not affect the risk for isolation of methicillin-resistant strains (data not shown).

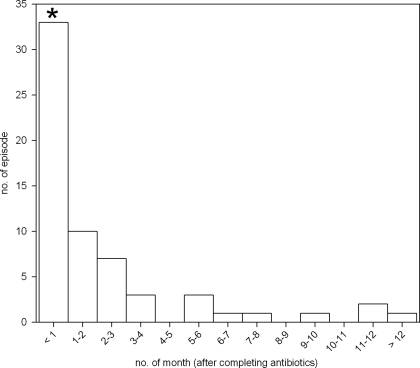

Relapse and Repeat Peritonitis

Of the 245 episodes, 33 (14.2%) developed relapse and 29 (12.5%) developed repeat CNSS peritonitis. The time frame of developing repeat peritonitis is summarized in Figure 3. Twenty (60.6%) of the repeat episodes developed within 3 mo after completion of antibiotics. Peritonitis caused by methicillin-resistant strains had a similar risk for relapse or repeat CNSS peritonitis as compared with the episodes caused by methicillin-sensitive strains (37.5 versus 27.9%; P = 0.35). The initial antibiotic regimen (cefazolin versus vancomycin) had no significant effect on the risk for relapse or repeat peritonitis (32.03 versus 27.9%; P = 0.6). Age, diabetic status, Charlson comorbidity score, concomitant exit-site infection of any bacterium, recent hospitalization, and recent antibiotic therapy did not have any effect on the risk for relapse or repeat CNSS peritonitis (data not shown). Because there were only two cases with concomitant CNSS exit-site infection, its effect on relapse and repeat peritonitis was not analyzed.

Figure 3.

Distribution histogram of the time of developing repeat peritonitis after antibiotic treatment was completed. *Relapse CNSS peritonitis by definition.

Relapse or repeat episodes had a similar primary response rate (91.2 versus 96.6%; P = 0.14); the complete cure rate was significantly lower than the other episodes (54.4 versus 76.6%; P = 0.002). For relapse or repeat episodes, treatment with effective antibiotics for 3 wk was associated with a significantly higher complete cure rate than the conventional 2-wk treatment (83.3 versus 46.7%; P = 0.047).

Discussion

In this study, we found that CNSS peritonitis usually had a satisfactory response to antibiotic therapy. Methicillin resistance is common, but the treatment outcome seems not to be affected when cefazolin is used as the first-line antibiotic. As compared with the conventional recommendation, a 3-wk course of antibiotic can probably achieve a higher cure rate in relapse or repeat episodes.

Our findings are similar but not identical to other reported series. The absolute incidence of CNSS peritonitis was 0.064 episode per patient-year of treatment in our study, as compared with 0.11 to 0.20 episode per patient-year as reported by Zelenitsky et al. (12). Similarly, Mujais (7) reported that CNSS peritonitis accounted for approximately 30% of all episodes, as compared with 11.4% in our study. Our previous report indicated that although Gram-positive organisms were the cause of PD-related peritonitis in >40% of our cases (5,25), S. aureus and streptococci contributed to a substantial proportion of the cases. Furthermore, distinct decrease in the incidence of peritonitis caused by CNSS was observed in late 1990s in the reports of Zelenitsky et al. (12) and Kim et al. (16), which corresponded to the initial period of our study. Taken together, these observations suggest that the incidence of CNSS peritonitis declined after the extensive application of flush-before-fill philosophy and disconnect system (26,27) but remained static thereafter because there has been little technological advance in this area.

In our study, the cure rate was 71%, as compared with 81% in the report of Troidle et al. (10). In our series, the prevalence of methicillin-resistant strain was 49.5%, as compared with previous reports of 38% by de Mattos et al. (28), 42% by Kim et al. (16), and 74% by Zelenitsky et al. (12). It is well reported that liberal prescription of antibiotics is common among family physicians of Hong Kong (29), which possibly explains the high prevalence of methicillin resistance in our center. In fact, we find that recent antibiotic use is a major risk factor of isolating methicillin-resistant strains.

It is important to note that we did not prove that cefazolin is as effective as vancomycin for treatment of CNSS peritonitis that is caused by methicillin-resistant strain. Our result, however, does show that in a setting of high prevalence of methicillin resistance, cefazolin remains an effective first-line agent before the bacterial antibiotic sensitivity is available, provided that the treatment is changed to vancomycin once the bacterial isolate is proved to be methicillin resistant. Although it has been argued that this strategy would inadvertently delay the use of effective antibiotic (i.e., vancomycin) in a considerable proportion of patients (18), our data show that the “delay” has no important clinical consequence. The response to treatment remains satisfactory, and the risk for peritoneal failure was not higher in patients with a “delay” switch to vancomycin (data not shown). Unfortunately, we do not have information on the peritoneal transport characteristics before and after the peritonitis episodes.

Similar to our previous observation on S. aureus peritonitis (25), most of the repeat episodes of CNSS peritonitis developed within 3 mo after completion of antibiotics. The result is distinctly different from that of our previous study on Enterobacteriaceae peritonitis (30), which found that repeat peritonitis occurred evenly in 1 yr after the index episode. Theoretically, relapse or early repeat CNSS peritonitis could be the result of catheter infection; however, fewer than 1% of the patients had concomitant CNSS exit-site infection, and exit-site infection was not associated with the treatment response in this study. Our observation is in line with the contemporary dogma that relapses or early repeats of CNSS peritonitis is a result of biofilm formation on the dialysis catheter (31,32). Unfortunately, we have no data on the efficacy of oral rifampicin or simultaneous Tenckhoff catheter exchange, which has been shown to be effective in preventing recurrent peritonitis caused by S. aureus (25) and Gram-negative organisms (30,33), respectively. Nonetheless, we found that a 3-wk course of antibiotic for relapse or repeat episodes was associated with a higher cure rate than the conventional 2-wk course. This approach somehow agrees with the current Ad Hoc Advisory Committee recommendation for the treatment of S. aureus and Pseudomonas peritonitis (13), both of which have a very high risk for relapse. Although a detailed comparison of relapse rate between bacterial species is beyond the scope of this study, our previous work showed that the relapse rate was 8.6% for S. aureus (25), 8.6% for culture-negative cases (34), 14.3% for Enterobacteriaceae (30), and 26% for Pseudomonas species (33), whereas it was 14.2% in this report.

There are a number of limitations of our study. Most important, data on antibiotic sensitivity were available only for episodes after 2000. The statistical power is therefore much limited when one analyzes the impact of methicillin resistance on the clinical outcome. Furthermore, the first-line antibiotic for a Gram-positive organism was not allocated in a randomized manner. In short, the regimen was changed from vancomycin to cefazolin in mid-1999 in our center. As a result, it is difficult to dissect the interactions among time effect, first-line antibiotic, prevalence of methicillin resistance, and treatment outcome. The number of episodes that were treated with a 3-wk course of antibiotic is also small, and it represents a highly selected group. Nonetheless, the benefit of a longer course seems to be genuine because these episodes should be the ones with worst prognosis (e.g., slow initial response or concomitant exit-site infection). Further studies would be needed to compare the benefit of prolonged antibiotic with other therapeutic approaches (e.g., simultaneous catheter exchange and rifampicin).

Conclusions

CNSS peritonitis remains a common complication of peritoneal dialysis. Methicillin resistance is common, but the treatment outcome remains favorable when cefazolin is used as the first-line antibiotic, with attention to the sensitivity report and prompt change to vancomycin once methicillin resistance is confirmed by sensitivity assay. A 3-wk course of antibiotic can probably achieve a higher cure rate in relapse or repeat episodes.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Chinese University of Hong Kong research accounts 6901031 and 8500282.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Piraino B: Peritonitis as a complication of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1956–1964, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oreopoulos DG, Tzamaloukas AH: Peritoneal dialysis in the next millennium. Adv Ren Replace Ther 7: 338–346, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szeto CC, Wong TY, Leung CB, Wang AY, Law MC, Lui SF, Li PK: Importance of dialysis adequacy in mortality and morbidity of Chinese CAPD patients. Kidney Int 58: 400–407, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szeto CC, Chow KM, Wong TY, Leung CB, Wang AY, Lui SF, Li PK: Feasibility of resuming peritoneal dialysis after severe peritonitis and Tenckhoff catheter removal. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1040–1045, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szeto CC, Leung CB, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Law MC, Wang AY, Lui SF, Li PK: Change in bacterial aetiology of peritoneal-dialysis-related peritonitis over ten years: Experience from a center in South-East Asia. Clin Microbiol Infect 10: 837–839, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloembergen WE, Port FK: Epidemiological perspective on infections in chronic dialysis patients. Adv Ren Replace Ther 3: 201–207, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mujais S: Microbiology and outcomes of peritonitis in North America. Kidney Int Suppl 103: S55–S62, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LF, Bernardini J, Johnston JR, Piraino B: Peritonitis influences mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2176–2182, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szeto CC, Wong TY, Chow KM, Leung CB, Li PK: Are peritoneal dialysis patients with and without residual renal function equivalent for survival study? Insight from a retrospective review of the cause of death. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 977–982, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prowant B, Nolph K, Ryan L, Twardowski Z, Khanna R: Peritonitis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: Analysis of an 8-year experience. Nephron 43: 105–109, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Troidle L, Gorban-Brennan N, Kliger A, Finkelstein F: Differing outcomes of gram-positive and gram-negative peritonitis. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 623–628, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zelenitsky S, Barns L, Findlay I, Alfa M, Ariano R, Fine A, Harding G: Analysis of microbiological trends in peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis from 1991 to 1998. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 1009–1013, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, Boeschoten E, Gupta A, Holmes C, Kuijper EJ, Li PK, Lye WC, Mujais S, Paterson DL, Fontan MP, Ramos A, Schaefer F, Uttley L: ISPD Ad Hoc Advisory Committee: Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations—2005 update. Perit Dial Int 25: 107–131, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khairullah Q, Provenzano R, Tayeb J, Ahmad A, Balakrishnan R, Morrison L: Comparison of vancomycin versus cefazolin as initial therapy for peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 22: 339–344, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gucek A, Bren AF, Hergouth V, Lindic J: Cefazolin and netilmycin versus vancomycin and ceftazidime in the treatment of CAPD peritonitis. Adv Perit Dial 13: 218–220, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamoto H, Hashikita Y, Itabashi A, Kobayashi T, Suzuki H: Changes in the organisms of resistant peritonitis in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial 20: 52–57, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kan GW, Thomas MA, Heath CH: A 12-month review of peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis in Western Australia: Is empiric vancomycin still indicated for some patients? Perit Dial Int 23: 465–468, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim DK, Yoo TH, Ryu DR, Xu ZG, Kim HJ, Choi KH, Lee HY, Han DS, Kang SW: Changes in causative organisms and their antimicrobial susceptibilities in CAPD peritonitis: A single center's experience over one decade. Perit Dial Int 24: 424–432, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vas SI: Peritonitis during CAPD: A mixed bag. Perit Dial Bull 1: 47–49, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keane WF, Alexander SR, Bailie GR, Boeschoten E, Gokal R, Golper TA, Holmes CJ, Huang CC, Kawaguchi Y, Piraino B, Riella M, Schaefer F, Vas S: Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis treatment recommendations: 1996 update. Perit Dial Int 16: 557–573, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flanigan MJ, Hochstetler LA, Langholdt D, Lim VS: Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis catheter infections: Diagnosis and management. Perit Dial Int 14: 248–254, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS): Performance Standards For Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 9th Informational Supplement: NCCLS Document M100–S9, Villanova, PA, NCCLS, 1999

- 23.Li PK, Ip M, Law MC, Szeto CC, Leung CB, Wong TY, Ho KK, Wang AY, Lui SF, Yu AW, Lyon D, Cheng AF, Lai KN: Use of intra-peritoneal (IP) cefepime as monotherapy in the treatment of CAPD peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 20: 232–234, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung CB, Szeto CC, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Wang AY, Lui SF, Li PK: Cefazolin plus ceftazidime versus imipenem/cilastatin monotherapy for treatment of CAPD peritonitis: A randomized controlled trial. Perit Dial Int 24: 440–446, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szeto CC, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Law MC, Chung KY, Yu S, Leung CB, Li PK: Staphylococcus aureus peritonitis complicating peritoneal dialysis: Review of 245 consecutive cases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 245–251, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li PK, Szeto CC, Law MC, Chau KF, Fung KS, Leung CB, Li CS, Lui SF, Tong KL, Tsang WK, Wong KM, Lai KN: Comparison of double-bag and Y-set disconnect systems in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A randomized prospective multicenter study. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 535–540, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li PK, Law MC, Chow KM, Chan WK, Szeto CC, Cheng YL, Wong TY, Leung CB, Wang AY, Lui SF, Yu AW: Comparison of clinical outcome and ease of handling in two double-bag systems in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 373–380, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Mattos EM, Teixeira LA, Alves VM, Rezenda e Resende CA, da Silva Coimbra MV, da Silva-Carvalho MC, Ferreira-Carvalho BT, Figueiredo AM: Isolation of me-thicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci from patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and comparison of different molecular techniques for discriminating isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 45: 13–22, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng R: An audit of antibiotic prescribing in general practice using sore throats as a tracer for quality control. Public Health 99: 174–177, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szeto CC, Chow VC, Chow KM, Lai RW, Chung KY, Leung CB, Kwan BC, Li PK: Enterobacteriaceae peritonitis complicating peritoneal dialysis: A review of 210 consecutive cases. Kidney Int 69: 1245–1252, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorman SP, Adair CG, Mawhinney WM: Incidence and nature of peritoneal catheter biofilm determined by electron and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Epidemiol Infect 112: 551–559, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepandj F, Ceri H, Gibb AP, Read RR, Olson M: Biofilm infections in peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: Comparison of standard MIC and MBEC in evaluation of antibiotic sensitivity of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Perit Dial Int 23: 77–79, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szeto CC, Chow KM, Leung CB, Wong TY, Wu AK, Wang AY, Lui SF, Li PK: Clinical course of peritonitis due to Pseudomonas species complicating peritoneal dialysis: A review of 104 cases. Kidney Int 59: 2309–2315, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szeto CC, Wong TY, Chow KM, Leung CB, Li PK: The clinical course of culture-negative peritonitis complicating peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 567–574, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]