Abstract

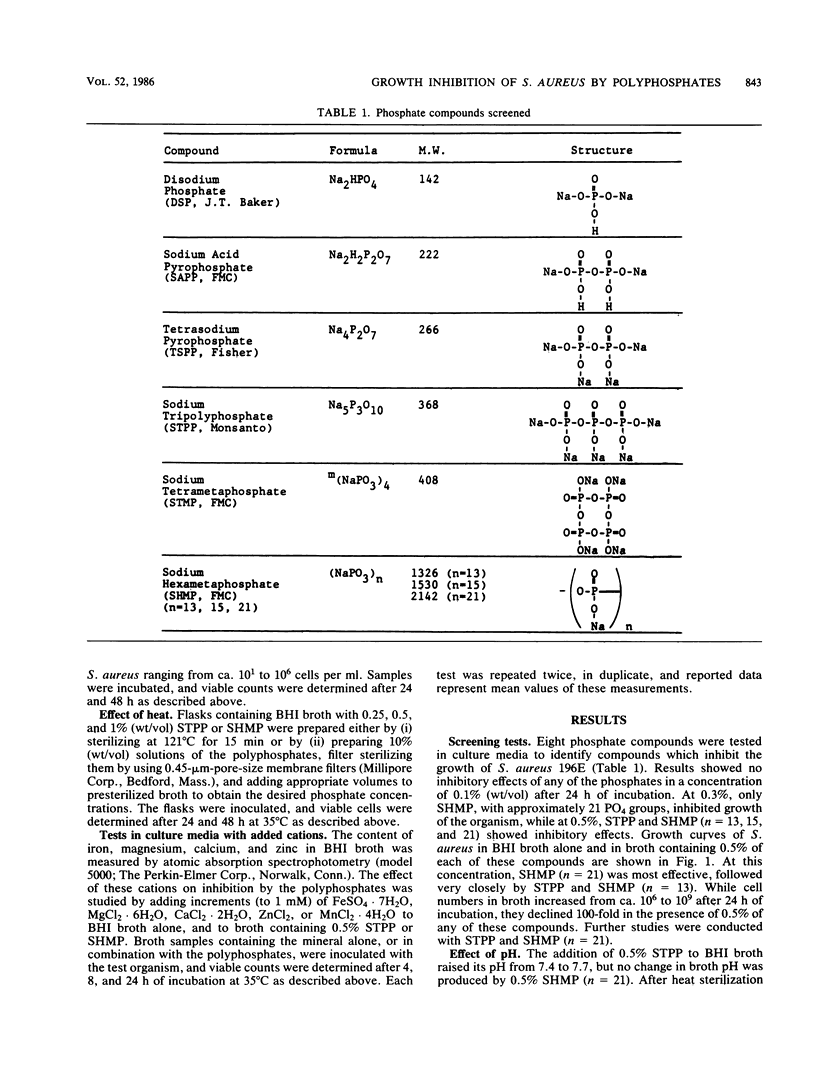

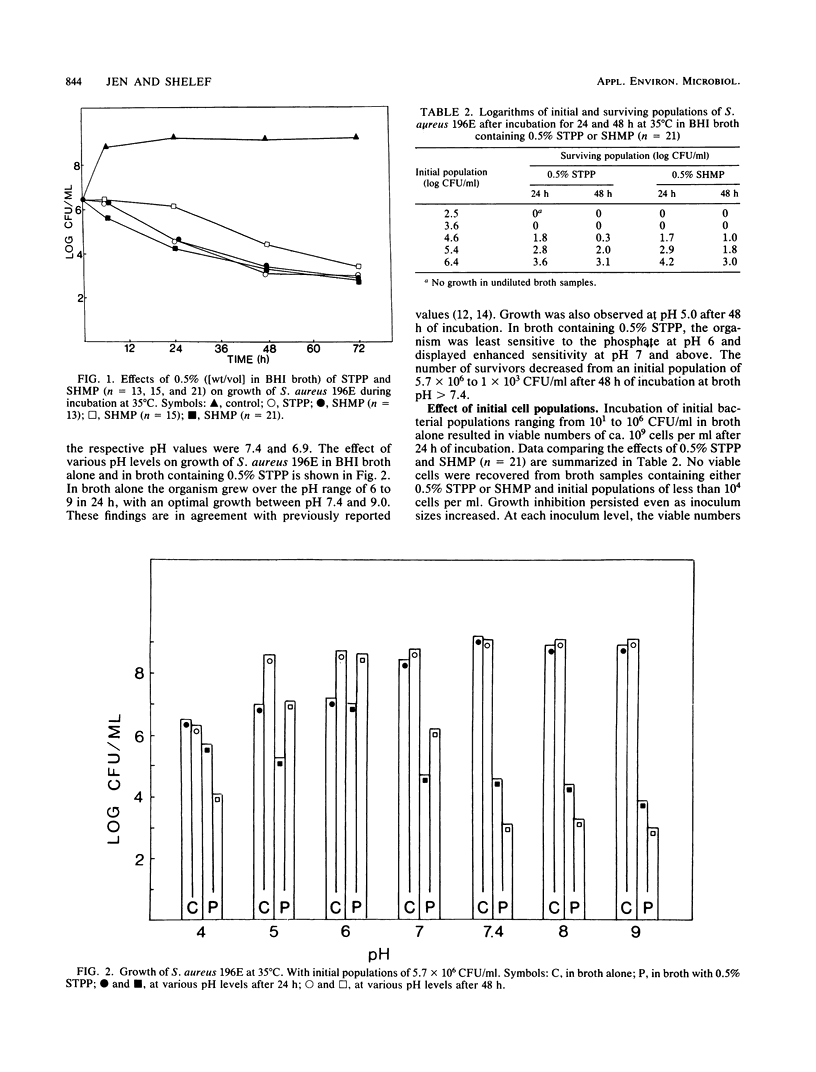

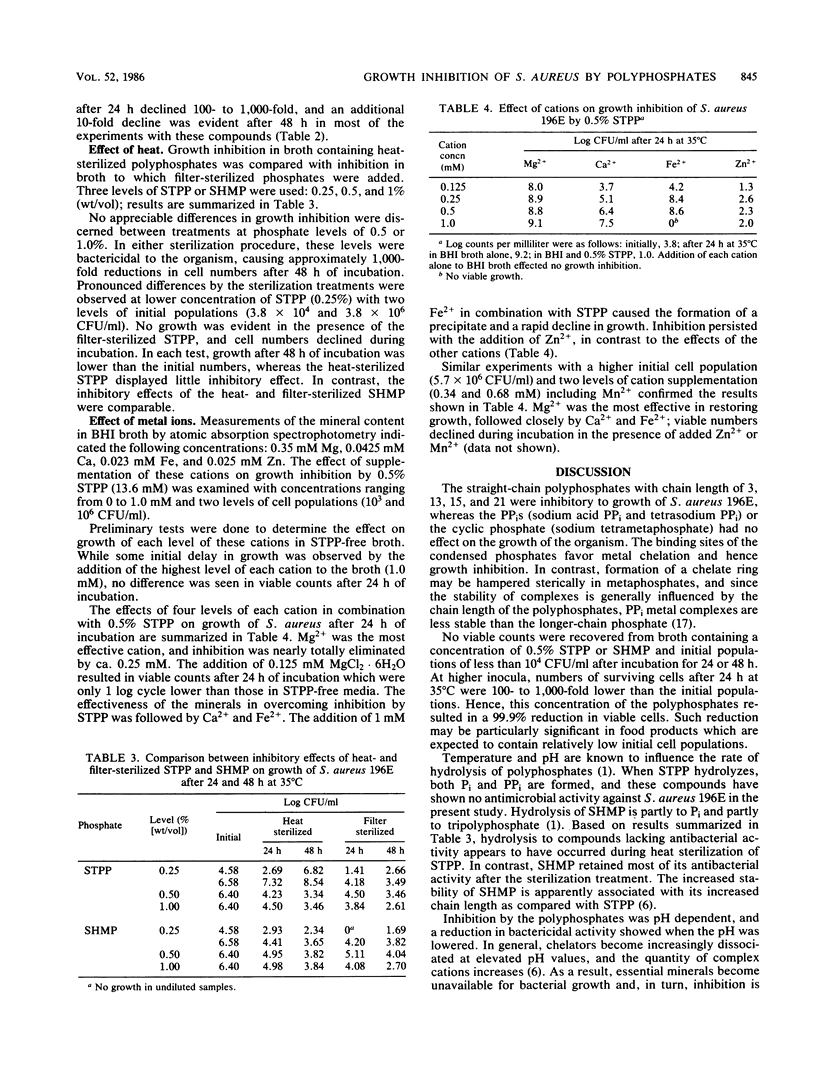

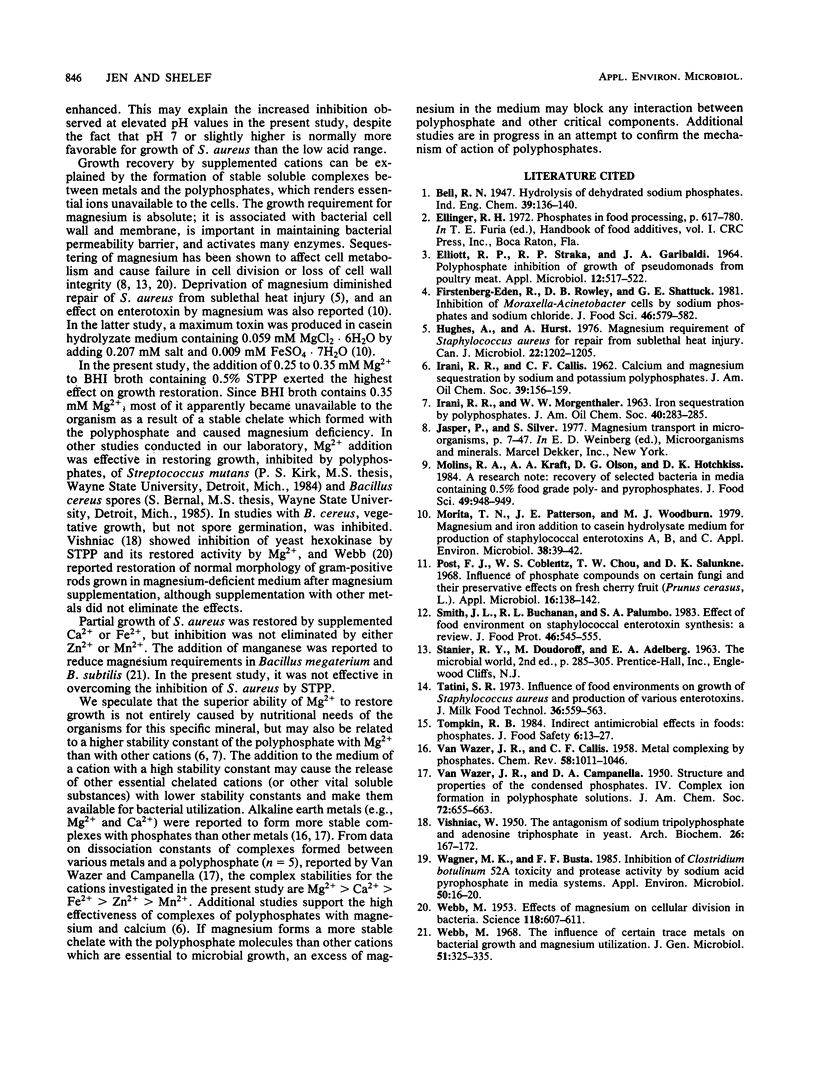

The effect of polyphosphates (eight compounds) on growth of Staphylococcus aureus 196E in brain heart infusion broth was studied. The organism was sensitive (in decreasing order) to chain polyphosphates with 21, 3, 13, and 15 PO4 groups, and bactericidal effects were observed with 0.5% of these compounds. No inhibition was effected by PPi or a metaphosphate. The inhibitory effects were pH dependent, and bacterial sensitivity was highest at pH greater than 7.4. Initial populations affected the number of survivors. No growth was observed after 24 h at 35 degrees C when the initial cell population was less than 10(4) CFU/ml, and a 100- to 1,000-fold decline in cell numbers occurred when initial populations were higher than 10(4) CFU/ml. Sodium tripolyphosphate produced less inhibition after heat sterilization (15 min, 121 degrees C) than after filter sterilization, whereas sodium hexametaphosphate (n = 21) retained most of its antimicrobial activity after heat sterilization. Supplementation of broth with Mg2+ was effective in overcoming inhibition by 0.5% sodium tripolyphosphate, and an addition of 0.25 to 1.0 mM cation restored most of the growth. Inhibition was partially eliminated by Ca2+ and Fe2+, but not by Zn2+ or Mn2+.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ELLIOTT R. P., STRAKA R. P., GARIBALDI J. A. POLYPHOSPHATE INHIBITION OF GROWTH OF PSEUDOMONADS FROM POULTRY MEAT. Appl Microbiol. 1964 Nov;12:517–522. doi: 10.1128/am.12.6.517-522.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A., Hurst A. Magnesium requirement of Staphylococcus aureus for repair from sublethal heat injury. Can J Microbiol. 1976 Aug;22(8):1202–1205. doi: 10.1139/m76-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita T. N., Patterson J. E., Woodburn M. J. Magnesium and iron addition to casein hydrolysate medium for production of staphylococcal enterotoxins A, B, and C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Jul;38(1):39–42. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.1.39-42.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post F. J., Coblentz W. S., Chou T. W., Salunkhe D. K. Influence of phosphate compounds on certain fungi and their preservative effects on fresh cherry fruit (Prunus cerasus, L.). Appl Microbiol. 1968 Jan;16(1):138–142. doi: 10.1128/am.16.1.138-142.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISHNIAC W. The antagonism of sodium tripolyphosphate and adenosine triphosphate in yeast. Arch Biochem. 1950 Apr;26(2):167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBB M. Effects of magnesium on cellular division in bacteria. Science. 1953 Nov 20;118(3073):607–611. doi: 10.1126/science.118.3073.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M. K., Busta F. F. Inhibition of Clostridium botulinum 52A toxicity and protease activity by sodium acid pyrophosphate in media systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985 Jul;50(1):16–20. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.1.16-20.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M. The influence of certain trace metals on bacterial growth and magnesium utilization. J Gen Microbiol. 1968 May;51(3):325–335. doi: 10.1099/00221287-51-3-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]