Abstract

Despite focused efforts to improve therapy, 5-yr survival rates for persons with advanced-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) remain discouragingly low. Clearly, early detection combined with strategies for local intervention, such as chemoprevention prior to SCC development, could dramatically improve clinical outcomes. Previously conducted oral cavity human chemoprevention trials, however, have provided mixed results. Although some therapies showed efficacy, they were often accompanied by either significant toxicities or circulating antiadenoviral antibodies. It is clearly apparent that identification of nontoxic, effective treatments is essential to prevent malignant transformation of oral epithelial dysplasias. This study employed cell lines isolated from human oral SCC tumors to investigate the effects of a freeze-dried black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) on cellular growth characteristics often associated with a transformed phenotype such as sustained proliferation, induction of angiogenesis, and production of high levels of reactive species. Our results demonstrate that RO-ET suppresses cell proliferation without perturbing viability, inhibits translation of the complete angiogenic cytokine vascular endothelial growth factor, suppresses nitric oxide synthase activity, and induces both apoptosis and terminal differentiation. These data imply that RO-ET is a promising candidate for use as a chemopreventive agent in persons with oral epithelial dysplasia.

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which comprises the vast majority of intraoral cancers, is a significant worldwide health problem (1,2). Furthermore, despite focused efforts to improve therapy, 5-yr survival rates for persons with advanced-stage oral SCC remain discouragingly low. These data are particularly disappointing because oral SCC arises in a visibly accessible site that is readily amenable to early detection and local treatment. Clearly, early detection combined with strategies for local intervention, such as chemoprevention prior to SCC development, could dramatically improve clinical outcomes.

The oral cavity is an attractive site for chemoprevention due to the capacity for direct visualization, which enhances the ability to diagnose lesions and monitor treatment. Previously conducted oral cavity human chemoprevention trials, however, have provided mixed results (3-6). A recent trial that used an attenuated adenovirus (ONYX-015) containing mouthwash to target p53 defective cells induced a 37% transient resolution of epithelial dysplasia (6). This treatment, however, was also accompanied by increases in circulating antiadenoviral antibody titers (6). Further, although systemic administration of vitamin A and its derivatives induced regression of premalignant oral lesions (3,4), these treatments were often accompanied by significant toxicities such as mucositis and hematologic disorders (4). Another complication observed in the vitamin A derivative trials was the relative resistance of oral cavity dysplastic epithelial lesions to multiagent treatment regimens (5). For persons with oral epithelial dysplasia, chemoprevention is likely to be necessary for the remainder of their lives. Subsequently, identification of nontoxic, effective treatments is essential to prevent malignant transformation of oral epithelial dysplasias.

Recent studies from our laboratories have shown that black raspberries possess potent chemopreventive effects at both the in vitro and in vivo levels (7-10). Dietary administration of freeze-dried black raspberries successfully inhibited nitrosamine-induced esophageal tumorigenesis in rats (7) and also prevented dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-initiated oral carcinogenesis in the hamster cheek pouch (8). In vitro studies, which showed that extracts prepared from freeze-dried black raspberries prevent benzo[a]pyrene-induced transformation of Syrian hamster embryo cells (9) and inhibit activation of the redox-responsive transcription activating factors nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and activating protein 1 (AP-1) (10), demonstrated freeze-dried black raspberries' reactive species scavenging and cytoprotective properties. In addition, our laboratories' phase I human clinical trials have confirmed that dietary administration of high dosages of freeze-dried black raspberries is well tolerated in humans (11).

This current study used cell lines isolated from human oral SCC tumors to investigate the effects of a freeze-dried black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) on cellular growth characteristics often associated with a transformed phenotype. Notably, these targeted cellular parameters recapitulate changes, including induction of the angiogenic switch and increased generation and persistence of reactive species, which are known to facilitate clinical progression of precancerous epithelial lesions to SCC (12-14). The findings from this study demonstrate that RO-ET suppresses cell proliferation without perturbing viability, inhibits both expression and translation of the complete angiogenic cytokine vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), suppresses nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity, and induces both apoptosis and terminal differentiation. These data, in conjunction with our previous study that established that large quantities of freeze-dried black raspberries are well tolerated by humans (11), imply that RO-ET is a promising candidate for use as a chemopreventive agent in persons with oral epithelial dysplasia.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Five cell lines derived from oral SCCs of the tongue that developed in men between the ages of 25 and 70 yr were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. All of the SCC cell lines are aneuploid and immortalized, have an epithelial morphology, and show growth rates ranging between 0.8 and 1.0 population doubling levels per day. Our laboratories have confirmed that these cell lines retain many characteristics of oral mucosa, including preservation of phase I and II enzymatic activities and production of high levels of VEGF protein (15,16). The cells were cultured in their optimal medium [Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12), 90%; heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 10%; “complete medium”] at 37°C and 5% CO2 for the majority of experiments. To permit a more concise evaluation of cellular response to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, an established inducer of VEGF and NOS) and reduce interfering effects from sera components, the cells were cultured in sera-free medium (“base medium”) for selected experiments. The majority of experiments employed four oral SCC cell lines (SCC 4, SCC 9, SCC 25, and SCC 2095). A fifth cell line (SCC 15), which was recently obtained, was included in the caspase-3 and transglutaminase functional assays.

Preparation of the Black Raspberry Ethanol Extract, RO-ET

As with the use of any natural product, valid concerns arise regarding the potential for batch-to-batch variations. Therefore, numerous quality assurance measures are taken to minimize variations in berry preparations. Although it is impossible to completely reduce the likelihood of some interbatch variations, our laboratories have implemented the following measures to dramatically reduce such differences. All black raspberries are obtained from a single farmer each year (Stokes Fruit Farm, Wilmington, OH). They are of the same variety (Jewel), grown in the same part of the field, and are picked at about the same degree of ripeness (when the majority of the berries in a cluster have turned black; this occurs within a period of 1–2 wk). The berries are harvested mechanically (with a picker) in a total period of 4 h. During the picking process, the berries are washed mechanically, and each batch is frozen at −20°C within an hour of the time of harvest. On average, in comparison of berries picked over a period of 5 yr, the variation in content of most components we measure appears to be no more that 10–20%. The ethanol extract (RO-ET) was prepared by a slight modification of the method reported in our recent publication (10). In this current study, ethanol, instead of methanol, was used as the berry solvent.

Determination of the Effects of RO-ET Dosages on Cell Viability and Proliferation

On the day of the assay, RO-ET working concentrations (10, 50, and 100 μg/ml) were prepared in complete medium. Control cultures received medium containing a comparable amount of vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 0.05%)], which was also the highest concentration of DMSO present in the experimental groups. Fresh medium containing either the appropriate RO-ET dose or DMSO was added every 24 h. Cell harvests were conducted at 24, 48, and 72 h after RO-ET challenge. Cell counts were conducted using a hemocytometer, and viabilities were determined using Trypan Blue dye exclusion. Previous studies conducted by our laboratories have shown an excellent agreement (viabilities comparable within 1%) between Trypan Blue exclusion and lactate dehydrogenase release assays (17).

Analyses to Establish Intracellular Presence of RO-ET

Black raspberries contain many compounds with chemopreventive properties. Among these are the anthocyanins, which are present in appreciable quantities in black raspberries. Therefore, anthocyanin content within the cultured SCC cells was used as an indicator of RO-ET cellular uptake. For these experiments, SCC cells were cultured in complete medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml RO-ET for 24 h. Vehicle control cultures were grown in complete medium plus 0.01% DMSO for 24 h. At harvest, cells were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C and then prepared for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-mass spectrosmetry (MS) analyses. The cell samples were dissolved in 90% solvent A (water plus 1% formic acid) and 10% solvent B (acetonitrile plus 1% formic acid) and then separated on a Symmetry C18 reversed-phase column and analyzed using a Waters 2695 gradient HPLC separation module equipped with a 996 photodiode array (PDA) UV/visible absorbance detector (Milford, MA). The solvent system consisted of a step gradient from 90% A to 50% B over 15 min, and the absorption spectra were recorded from 200 to 800 nm with the in-line PDA detector. Mass spectrometry was conducted on a quadrupole ion tunnel mass spectrometer equipped with a Z-spray electrospray ionization (ESI) source.

Evaluation of RO-ET's Effects on Expression and Translation of the Complete Angiogenic Cytokine, VEGF

Semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR; using glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the housekeeping gene] was conducted on cellular RNA to determine the effects of RO-ET on VEGF expression. RNA was extracted by standard methods during the following culture conditions: log growth, 72-h sera deprivation, 72-h sera deprivation followed by a 6-h challenge with TNFα (100 U/ml), and 72-h sera deprivation followed by a 6-h challenge with RO-ET. Water controls and controls without RT-PCR were run in all cases. Amplifications used custom primers designed by Primer Express (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT) using an intron-based primer for GAPDH.

As modification in RNA levels does not always reflect altered protein status, a separate series of experiments was also conducted to determine the effect of RO-ET on VEGF protein synthesis. The experimental groups used for these studies were log growth + 0.01% DMSO (vehicle control) and log growth + 24-h treatment with RO-ET (100 μg/ml). At harvest, the media was collected, volume recorded, and samples stored at −80°C until analyses. VEGF levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), and VEGF levels were reported as picograms per milligram of cell protein. The cell samples from these experimental groups were used to determine protein levels and NOS functional activities.

Evaluation of RO-ET's Effects on Nitric Oxide Synthase Functional Activities

At harvest, the cells were suspended in Tris buffer [pH 7.4 + a protease inhibitor cocktail (#P8340, Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO)], lysed by liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw, and centrifuged, and the volume of lysate was recorded prior to storage at −80°C. NOS activity was determined by a spectrophotometric assay (37°C, pH 7.4, 550 nm), which monitored the ability of NOS to transfer electrons from an electron donor [nicotinaminde dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)] to an electron acceptor (acetylated cytochrome c). The assay system included either NOS standards or cell samples in addition to the following (in final concentrations): superoxide dismutase (100 U/ml), catalase (10 U/ml), flavin adenine dinucleotide (4 μM), riboflavin 5′-monophosphate (4 μM), bovine serum albumin (0.1 mg/ml), acetylated cytochrome c (100 μM), and NADPH (0.2 mM). A five-point NOS standard curve (ranging from 0.05 to 5.0 U/ml, #N1783, Sigma Chemical Company) was conducted with each assay. One unit of NOS activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1.0 nmol NO per minute at 37°C, pH 7.4. Results were expressed as units per milligram of protein.

Assessment of RO-ET's Effects on Induction of Apoptosis by Monitoring Caspase-3 Activity

SCC lines 4, 9, 15, 25, and 2095 were treated as follows: DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS (complete medium, log growth) and complete medium + 100 μg/ml RO-ET (3-, 6-, and 24-h harvests). The log-growth cultures received an equivalent amount of DMSO (0.01%) as the RO-ET cultures. At harvest, a representative aliquot of each experimental group was frozen for protein determination. Cell extracts for determination of caspase-3 activity were prepared by liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw. The caspase-3 activities were determined using a fluorometric assay (400-nm excitation, 505 emission, 30°C, pH 7.4) monitoring cleavage of 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin–labeled aspartate-glutamate-valine-aspartate (DEVD) substrate (Calbiochem, #QIA107, La Jolla, CA). Each assay included a concurrently conducted five-point standard curve [human recombinant caspase-3 (Calbiochem, #235400)] with 1 unit of activity defined as the amount of enzyme that will cleave 1.0 pmol of the DEVD substrate per minute at 30°C, pH 7.4. Results were expressed as units of activity per milligram of protein.

Evaluation of RO-ET's Effects on Transglutaminase Function

SCC lines 4, 9, 15, 25, and 2095 were treated as follows: complete medium (log growth) and complete medium + 100 μg/ml RO-ET (3-, 6-, and 24-h harvests), with the log-growth cultures receiving an equivalent amount of DMSO (0.01%) as the RO-ET cultures. At harvest, a representative aliquot of each experimental group was frozen for protein determination. Cell extracts for determination of transglutaminase activity were prepared by liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw. Transglutaminase activities were determined by the use of the Covalab Transglutaminase Colorimetric Microassay (Covalab, Lyon, France), which monitored the formation of γ-glutamyl cadaverine biotin (450 nm, pH 6.0, 37°C). With each assay, a five-point standard curve (guinea pig transglutaminase, #T5398, Sigma Chemical Company) and negative control (inclusion of the transglutaminase inhibitor EDTA) were conducted. Results were expressed as milliunits of activity per milligram of protein.

Determination of Cellular Protein Levels

Protein levels were determined by the Lowry method, using bovine γ-globulin as the standard protein (18).

Statistical Analysis

Duncan's multiple-comparison test was used to assess the effects of RO-ET on cell viability and proliferation. The two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate RO-ET's effects on NOS function. The effects of RO-ET on cellular VEGF production were analyzed by a Yates corrected χ2 test. The level of significance was established at the 95% confidence interval (α < 0.05).

Results

RO-ET Significantly Inhibits SCC Cell Proliferation While Preserving Cell Viabilities

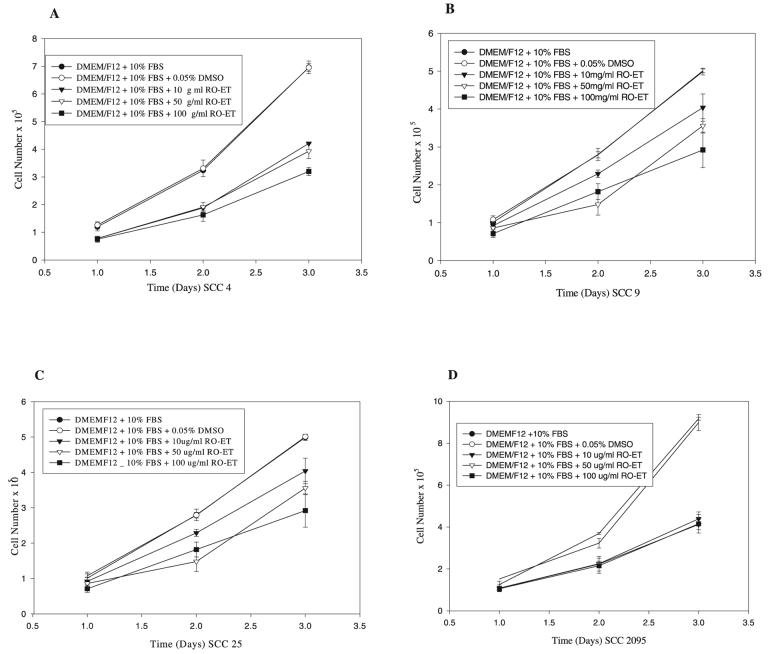

Time-course (24, 48, and 72 h) dose-response studies showed that inclusion of the RO-ET extract suppressed proliferation in each oral SCC cell line evaluated. Regardless of dose, at the 72-h harvest point, all RO-ET–treated cultures (10, 50, and 100 μg/ml) showed significantly reduced cell numbers relative to either log-growth or vehicle (0.01% DMSO) controls (P < 0.05, Duncan's multiple-comparison test, n = 8 for each group). Our results also demonstrate dose-dependent growth suppression, with cell numbers decreasing with increasing RO-ET concentration. In contrast, cell viabilities remained comparable (>97%) among all experimental groups at all timed harvest points (Fig. 1). As would be anticipated from cells obtained from human donors, our results show cell line–dependent differences in cell growth capacities (Fig. 1). These data, however, also show that RO-ET's effects are not donor dependent as all cell lines tested showed inhibition of cell growth during inclusion of RO-ET.

Figure 1.

Inclusion of black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) significantly suppresses squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell proliferation without perturbing cell viabilities. SCC cells were cultured in optimal media that included either RO-ET (10, 50, and 100 μg/ml), 0.05% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle control), or no inclusions (log-growth control). At the 72-h time point, all RO-ET–treated cultures showed reduced cell numbers relative to either log-growth or vehicle control cultures (P < 0.05, Duncan's multiple-comparison test, n = 8 for each group). Our results also demonstrate dose-dependent growth suppression, with cell numbers decreasing with increasing RO-ET concentrations. Comparable cell numbers were obtained in the log and vehicle control cultures. Cell viabilities remained comparable (>97%) among all experimental groups at all time points. A: SCC line 4. B: SCC line 9. C: SCC line 25. D: SCC line 2095.

Extracts from Freeze-Dried Black Raspberries Are Readily Internalized in Human Oral Keratinocytes, Resulting in Detectable Intracellular Levels of Anthocyanin Target Compounds

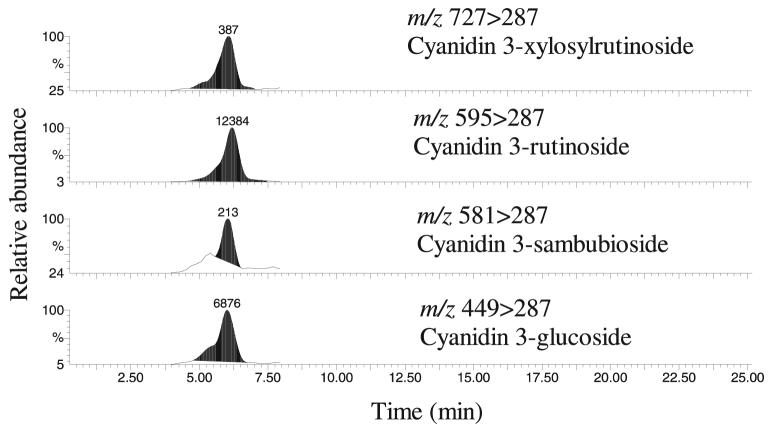

Cell lysates obtained from log-growth oral SCC cultures showed that no anthocyanins were detectable in control (RO-ET–free) cultures. In contrast, quantifiable levels of all four anthocyanins known to be present in black raspberries (cyanidin 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-xylosylrutinoside, cyanidin 3-rutinoside, and cyanidin 3-sambubioside) were identified in the RO-ET–treated cultures (Fig. 2). These data confirm internalization of RO-ET by demonstration of detectable intracellular levels of the targeted, bioactive compounds.

Figure 2.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-mass spectrometry (MS) analyses confirm uptake of black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) by oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells. Following a 24-h culture in optimal medium + 100 μg/ml RO-ET, SCC cells were harvested and frozen, and samples were prepared for HPLC-MS analyses. Our results confirm the presence of all four anthocyanins known to be present in black raspberries, that is, cyanidin 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-xylosylrutinoside, cyanidin 3-rutinoside, and cyanidin 3-sambubioside, in RO-ET within treated SCC cells. No anthocyanins were detected in the dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle control cultures.

RO-ET Inhibits Both Expression and Translation of VEGF

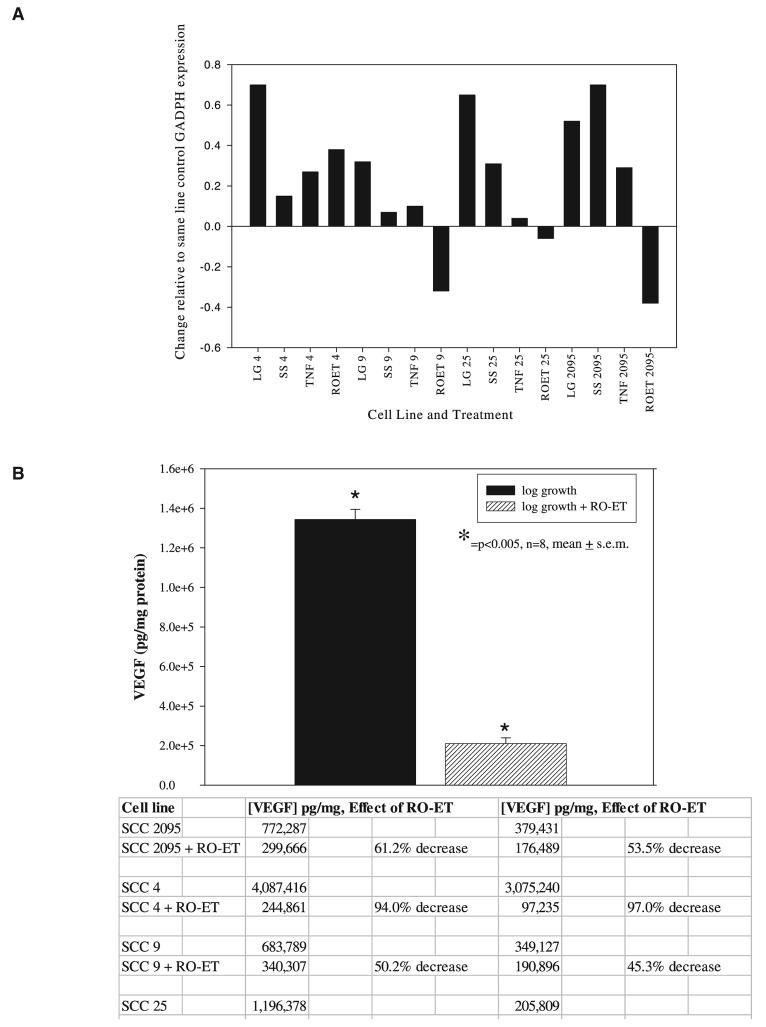

Semiquantitative RNA analyses (using the gel-digitizing software UN-SCAN-IT™ gel version 5.1, Silk Scientific, Orem, UT) were conducted to evaluate the effects of the proinflammatory cytokine and VEGF inducer TNFα and RO-ET exposure on VEGF gene expression. The data are depicted as the change in expression relative to message level of the housekeeping gene GAPDH in the same cell line sera-deprived control culture (Fig. 3A). Not unexpectedly, all four cell lines evaluated showed highest VEGF expression during log growth. Cell line–dependent differences in VEGF expression were also apparent (Fig. 3A). Only two lines responded to challenge with the VEGF-inducing cytokine TNFα with increases, albeit modest, in VEGF expression relative to their sera-deprived control cultures. These semiquantitative analyses showed that RO-ET exposure reduced VEGF expression in three of four cell lines evaluated.

Figure 3.

(A) Inclusion of black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET, 100 μg/ml) suppressed vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA levels in three of four squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell lines. Semiquantitative RNA analyses were conducted on SCC cellular RNA obtained during the following culture conditions: log growth, 72-h sera deprivation, 72-h sera deprivation followed by a 6-h challenge with tumor necrosis factor alpha (100 U/ml), and 72-h sera deprivation followed by a 6-h challenge with RO-ET (100 μg/ml). The data are depicted as the change in expression relative to message level of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the same cell line sera-deprived control culture. In three of four cell lines evaluated, introduction of RO-ET reduced VEGF expression. (B) Inclusion of RO-ET (100 μg/ml) significantly inhibited SCC cell VEGF production in each cell line evaluated. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analyses were conducted to determine SCC cell VEGF production during the following culture conditions: log growth and log growth + RO-ET (100 μg/ml, 24 h). Results are expressed as picograms per milligram of protein. RO-ET significantly inhibited SCC VEGF production in each cell line tested (P < 0.005, n = 8, Yates corrected χ2 test).

Because alterations in gene expression do not always equate to changes in the respective proteins, studies were also conducted to assess RO-ET's effects on VEGF protein levels. Results revealed cell line–associated differences (∼20-fold) in VEGF protein levels during log growth, findings that are consistent with the cell lineage from the outbred human population (Fig. 3B). These data also show that RO-ET treatment significantly suppressed VEGF release during culture in complete medium in all eight experiments (n = 8, P < 0.005, Yates corrected χ2 test).

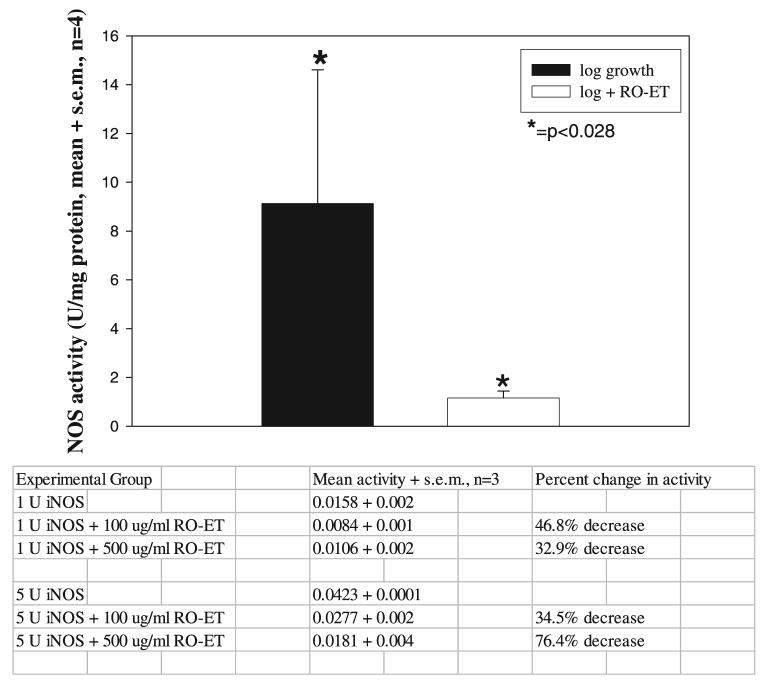

Inclusion of RO-ET Significantly Suppresses NOS Activity in SCC Cell Lysates and Directly Inhibits Activity of Purified NOS 2 Enzyme

NOS functional assay results displayed a 10-fold, cell line–associated range in NOS activities (2.5–25 U/mg protein) during log growth. The cell line (SCC 4) that demonstrated the greatest NOS activities also demonstrated the highest VEGF production, findings that may reflect the contribution of reactive nitrogen species in signal transduction and VEGF gene expression. Regardless of the heterogeneity of NOS activities during log growth, inclusion of RO-ET for 24 h during culture in complete medium significantly suppressed NOS activities in all four cell lines tested (P < 0.028, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) significantly inhibits squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cellular nitric oxide synthase (NOS) function. Functional NOS activities were determined in cells harvested during the following culture conditions: log growth and log growth + RO-ET (100 μg/ml, 24-h treatment). Additional assays were conducted to determine the effects of RO-ET on functional activity of purified NOS enzyme. Results are expressed as units per milligram of protein (1 unit of NOS activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1.0 nmol nitric oxide per minute at 37°C, pH 7.4). Our data show that RO-ET significantly inhibits SCC cellular NOS function (P < 0.028, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, n = 4) and also directly suppresses NOS enzymatic activity.

There are two plausible, not mutually exclusive mechanisms by which RO-ET could suppress NOS activities, that is, reduction in NOS protein levels via suppression of signal transduction and NOS gene expression or by direct inhibition of existing NOS protein. Additional experiments were conducted to test this second mechanism. Inducible NOS (iNOS) protein (derived from murine macrophages, #N1783, Sigma Chemical Company) was incubated (30 min, 37°C) with either 100 or 500 μg/ml of RO-ET prior to the NOS assay. The iNOS controls were incubated with vehicle only (0.01% DMSO) under similar conditions. Inclusion of RO-ET directly suppressed NOS function (Fig. 4). Furthermore, a dose-dependent effect, in which greater suppression was observed with the higher RO-ET concentration, was observed in the five U (higher activity) assays.

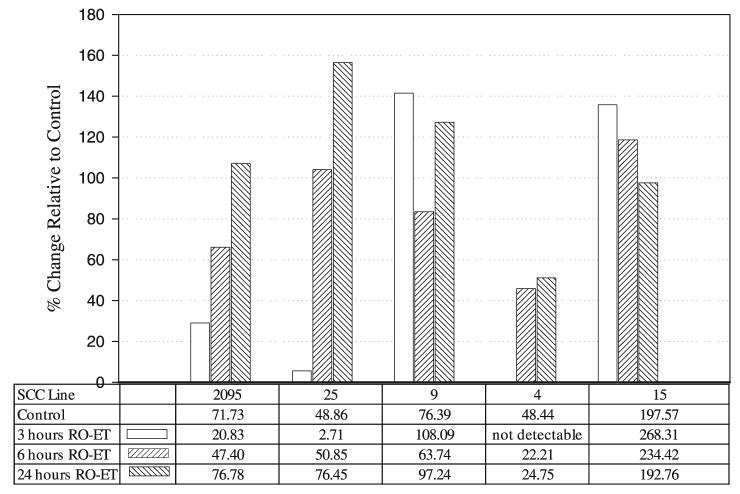

RO-ET Induces Caspase-3 Functional Activity

The five SCC cell lines used for the caspase functional assays showed over a twofold variation in caspase-3 function during log growth (Fig. 5). RO-ET increased caspase-3 activities in four of five cell lines (Fig. 5). Our data also show that the extent (increases in caspase-3 ranged from 7% to 57%) and time of caspase induction were cell line dependent. Although two cell lines (SCC 9 and 15) demonstrated highest caspase increases at 3 h after treatment, SCC 2095 and SCC 25's greatest caspase induction occurred at 24 h. The single cell line that was refractory to RO-ET's induction of caspase activity (SCC 4) did, however, show an appreciable (119%) increase in transglutaminase activity following RO-ET treatment (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Effect of black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) on caspase-3 activity. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell cultures were harvested for determination of caspase-3 functional activity during the following culture conditions: log growth and log growth + 100 μg/ml RO-ET (3-, 6-, and 24-h harvests). Caspase activity was determined by monitoring the cleavage of a labeled DVED substrate. Results are expressed as percent change in enzyme activity relative to the same cell line–matched log-growth control (units per milligram of protein with 1 unit of activity defined as the amount of enzyme that will cleave 1.0 pmol of the aspartate-glutamate-valine-aspartate (DVED) substrate per minute at 37°C, pH 7.4).

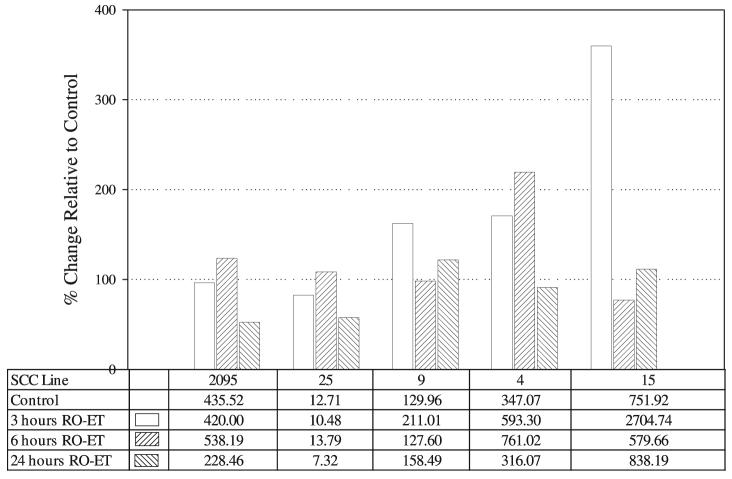

Figure 6.

Effect of black raspberry ethanol extract (RO-ET) on transglutaminase activity. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell cultures were harvested for determination of transglutaminase functional activity during the following culture conditions: log growth and log growth + 100 μg/ml RO-ET (3-, 6-, and 24-h harvests). Transglutaminase activity was determined by monitoring the formation of γ-glutamyl cadaverine biotin. Results (reported as milliunits per milligram of protein) are expressed as percent change in enzyme activity relative to the same cell line–matched log-growth control.

RO-ET Induces Activation of the Differentiation- and Apoptosis-Associated Transglutaminase Enzyme(s)

The transglutaminase assays showed that RO-ET treatment uniformly increased transglutaminase activities in all five cell lines evaluated (Fig. 6). The extent of activation, which varied among the cell lines, ranged from an 8.5% to 260% increase. In each cell line, the greatest increase in transglutaminase function was observed at either the 3- or 6-h (not 24-h) time points, which suggests that RO-ET enhances functional activities of existing transglutaminase enzymes.

RO-ET treatment also resulted in marked increases in cornified envelope formation, as assessed by phase contrast microscopic appearance, in each cell line tested. This increase in differentiation was also apparent during cell harvesting. Due to the changes in specific gravity of cornified envelopes, increases in both centrifuge speed and time were necessary to pellet the RO-ET–treated samples (data not shown).

Discussion

Numerous chemopreventive compounds have demonstrated abilities to inhibit cellular proliferation (19-21). The respective mechanisms of action for these agents' growth suppression, however, have not been completely defined. Some compounds such as ellagic acid induce mitochondrial perturbations that result in apoptosis (19), whereas other agents such as epigallocatechin-3-gallate and curcumin initially inhibit signal transduction, which ultimately induces apoptosis (20,21). Notably, RO-ET treatment demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of cell growth without reducing cell viability, a feature that is distinct from many other chemopreventive compounds (15,19,20). Our data, in conjunction with previous work from our laboratories that demonstrated RO-ET's suppression of NF-κB and AP-1 (9,10), suggest multimodal mechanisms of action for RO-ET's antiproliferative effects, that is, inhibition of reactive species–mediated signal transduction in conjunction with induction of apoptotic/differentiation pathways.

Conversion to the “angiogenic phenotype”, characterized by epithelial cell production of high levels of angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF, facilitates malignant transformation in dysplastic epithelial lesions (22,23). Relative to oral cancers, analyses have confirmed the clinical importance of tumor VEGF levels. Oral cancers that demonstrate high VEGF levels are more clinically aggressive and are associated with a markedly poorer overall prognosis (24). Similar to these more-aggressive oral cancers, the SCC cell lines used for this study retain an angiogenic phenotype as demonstrated by their high VEGF production (>200-fold and >6-fold relative to human prostate and ovarian carcinoma cells, respectively) (25,26). Our data also show that RO-ET significantly inhibits oral SCC VEGF production at concentrations that compare favorably with other VEGF-inhibiting chemopreventive compounds (25). We speculate that RO-ET's suppression of VEGF production reflects its abilities to scavenge reactive species that mediate signal transduction. Previously, we demonstrated that freeze-dried black raspberry extracts significantly inhibit activation of the reactive species-responsive, and VEGF-inducing transcription activating factor, AP-1 (10). Recently, Hou et al. showed an association between the chemical structures of anthocyanins and their signal transduction inhibitory activities, which provided further insights into anthocyanins' modulation of intracellular signaling (27). Notably, the chemical structure that Hou et al. determined was essential to suppress signal transduction, that is, an ortho-dihydroxyphenyl, is present on cyanidin (27).

Results from the NOS assays suggest multifaceted roles for RO-ET in modulation of nitric oxide chemistry. We speculate the NOS inhibition in RO-ET–treated cells reflects, at least partially, reduced levels of NOS protein as a result of RO-ET's suppression of signal transduction and gene expression. The data from the RO-ET NOS 2 co-incubation experiments imply a second mechanism for RO-ET–mediated NOS inhibition, that is, direct scavenging of NADPH's electrons, thereby limiting the reducing equivalents necessary for NOS function. Relative to other human cells, NOS activities are moderate to high in cultured oral SCC cells. Oral SCC cell NOS activities were comparable with levels detected in human neutrophils, a phagocyte population that employs high levels of reactive nitrogen species for microbiocidal activity (28). Similar to VEGF, there is a positive association between elevated NOS and progression of head and neck SCC as highest NOS activities are detected in the most aggressive cancers (29). Because of the well-recognized contribution of sustained high levels of reactive nitrogen species in malignant transformation and cancer progression (14,30-32), NOS inhibitors are currently being investigated as promising chemopreventive agents (33,34).

The cysteine protease caspase-3 serves in the execution phase of apoptosis. Relative to other well-established inducers of keratinocyte apoptosis such as UVB, RO-ET treatment resulted in >250-fold higher induction of caspase-3 (35). We propose two potential mechanisms whereby RO-ET induces apoptosis. Although antioxidants generally inhibit reactive species chemistry, under select circumstances, antioxidants themselves undergo oxidation reactions (36,37). Therefore, RO-ET may serve as a mitochondrial prooxidant that disrupts mitochondrial membrane integrity, releasing cytochrome c and ultimately inducing the apoptotic cascade. A related mechanism is introduced by recent studies by Shilo et al. (38). These investigators demonstrated that selenite scavenged electrons from mitochondrial complex I, resulting in NADH oxidation, sensitizing the mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and releasing cytochrome c (38). Our RO-ET–NOS 2 co-incubation results imply that this second mechanism, that is, electron acceptance by RO-ET at mitochondrial respiratory chain complex(es), is also feasible for RO-ET's induction of caspase-3.

RO-ET treatment also augmented transglutaminase activities. Human keratinocytes possess two transglutaminase isoforms, which include a membrane-bound enzyme associated with keratinocyte differentiation (TG1) as well as a soluble, apoptosis-associated enzyme (TG2) (35,39). Although both TG isoforms induce protein cross linking, TG1's protein substrates are associated with cornified envelope formation, for example, involucrin, whereas TG2 activation results in a generalized protein cross linking that induces apoptosis (40,41). Aspects of our data, such as the higher number of cornified envelopes and increased caspase-3 activity following RO-ET treatment, imply that RO-ET up-regulated both terminal differentiation and apoptotic associated pathways. Our cellular harvesting protocol, however, did not specifically segregate the membrane-bound TG1 from the soluble TG2 isoform. Notably, studies by Rorke and Jacobberger, which showed that increased function of the TG2 and not the TG1 isoform correlated with increased formation of cornified envelopes, suggest a potential overlap in keratinocyte transglutaminase cellular functions (39). SCC cell transglutaminase activities range between 0.014 and 2.7 U/mg following RO-ET treatment. These data compare favorably with the findings of Rorke and Jacobberger, who evaluated the effects of transforming growth factor β1 on human papillomavirus 16–immortalized keratinocytes (39). Additional experiments are in progress to clarify which transglutaminase isoform(s) are affected by RO-ET.

In summary, RO-ET suppresses several biochemical mechanisms whose activation is known to facilitate malignant transformation while concurrently up-regulating apoptotic and or terminal differentiation pathways. Our data also show that, due to its range of chemopreventive properties, RO-ET is unique; for example, studies by Balasubramanian et al. show that (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate treatment of keratinocytes induces cellular differentiation but not apoptosis (42).

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by NIH R21 CA111210 (Mallery) and NIH R01 CA103180 (Stoner). We would like to thank our colleagues Dr. Gary D. Stoner for his intellectual contributions and Dr. Stephen S. Hecht and Mr. Steven Carmella of the University of Minnesota for characterization and provision of the RO-ET extract. The authors also wish to acknowledge Mr. Dale Stokes and Stokes Berry Farm, who provided the black raspberries that were used for these studies, and Mr. Jeffrey A. Ruttencutter of the University of Illinois, who assisted in the development and execution of protocols..

References

- 1.Forastiere AA. Head and neck cancer: overview of recent developments and future direction. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–11. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Clayman GL, Shin DM, Myers JN, Gillenwater AM, et al. Biochemoprevention for dysplastic lesions of the upper aerodigestive tract. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:1083–1089. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.10.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toma A, Bonelli L, Sartoris A, Mira E, Antonelli A, et al. 13-cis Retinoic acid in head and neck cancer chemoprevention: results of a randomized trial from the Italian head and neck chemoprevention study group. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:1297–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin DM, Mao L, Papadimitrakopoulou VM, Clayman G, El-Naggar A, et al. Biochemopreventive therapy for patients with premalignant lesions of the head and neck and p53 gene expression. JNCI. 2000;92:69–73. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudin CM, Cohen EEW, Pappdimitrakopoulou VA, Silverman S, Recant W, et al. An attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, as mouthwash therapy for premalignant oral dysplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4546–4552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kresty LA, Morse MA, Morgan C, Carlton PS, Lu J, et al. Chemoprevention of esophageal tumorigenesis by dietary administration of lyophilized black raspberries. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6112–6119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casto BC, Kresty LA, Kraly CL, Pearl DK, Knobloch TJ, et al. Chemoprevention of oral cancer by black raspberries. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:4005–4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xue H, Aziz RM, Sun N, Cassady JM, Kamedulis LM, et al. Inhibition of cellular transformation by berry extracts. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:351–356. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C, Huang Y, Li J, Hu W, Aziz R, et al. Inhibition of benzo(a)pyrene diol-epoxide-induced transactivation of activated protein 1 and nuclear factor κB by black raspberry extracts. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6857–6863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoner G, Sardo C, Apseloff G, Mullet D, Wargo W, et al. Pharmacokinetic of anthocyanins and ellagic acid in healthy volunteers fed freeze-dried black raspberries for 7 days. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1153–1164. doi: 10.1177/0091270005279636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitadai Y, Onogawa S, Kuwai T, Matsumaura S, Hamada H, et al. Anigogenic switch occurs during the precancerous stage of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lingen MW. Angiogenesis in the development of head and neck cancer and its inhibition by chemopreventive agents. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:153–164. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wink DA, Vodovotz Y, Laval J, Laval F, Dewhirst MW, et al. The multifaceted roles of nitric oxide in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:711–721. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinaldi AL, Morse MA, Fields HW, Rothas DA, Pei P, et al. Curcumin activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor yet significantly inhibits (−)-benzo(a)pyrene-7R-trans-7,8-dihydrodiol bioactivation in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells and oral mucosa. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5451–5456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallery SR, Shenderova A, Pei P, Begum S, Ciminieri JR, et al. Effects of 1-hydroxycamptothecin, delivered from locally injectable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres, in a murine human oral squamous cell carcinoma regression model. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:1713–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallery SR, Pei P, Kang J, Ness GM, Ortiz R, et al. Controlled-release of doxorubicin from poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres significantly enhances cytotoxicity against cultured AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2001;20:2817–2826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losso JN, Bansode RR, Trappey A, Bawadi HA, Truax R. In vitro anti-proliferative activities of ellagic acid. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:672–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masuda M, Suzui M, Weinstein IB. Effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on growth, epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathways, gene expression, and chemosensitivity in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4220–4229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggarwal S, Takada Y, Singh S, Myers JN, Aggarwal BB. Inhibition of growth and survival of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by curcumin via modulation of nuclear factor-κB signaling. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:679–692. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soufla G, Sifakis S, Baritaki S, Zafiropoulos A, Koumantakis E, et al. VEGF, FGF2, TGB1 and TGFBR1 mRNA expression levels correlate with the malignant transformation of the uterine cervix. Cancer Lett. 2005;221:105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoeffner DJ, Matheny SL, Akahane T, Factor V, Berry A, et al. VEGF contributes to mammary tumor growth in transgenic mice through paracrine and autocrine mechanisms. Lab Invest. 2005;85:608–623. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith BD, Smith GL, Carter D, Saski CT, Haffty BG. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor protein levels in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2046–2052. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh RP, Tyagi AK, Shanalakshmi S, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Grape seed extract inhibits advanced human prostate tumor growth and angiogenesis and upregulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:733–740. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belotti D, Paganoni P, Manenti L, Garofalo A, Marchini S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP9 and MMP2) induce the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by ovarian carcinoma cells: implication for ascites formation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5224–5229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou DX, Kai K, Li JJ, Lin S, Terahara N, et al. Anthocyanidins inhibit activator protein 1 activity and cell transformation: structure-activity relationship and molecular mechanisms. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:29–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitsuke Y, Lee J-D, Shimizu H, Uzui H, Iwasaki H, et al. Nitric oxide synthase activity in peripheral polymorphonuclear leukocytes in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallo O, Masini E, Morbidelli L, Franchi A, Fini-Storchi I, et al. Role of nitric oxide in angiogenesis and tumor progression in head and neck cancer. JNCI. 1998;90:587–596. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1994;305:253–264. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burney S, Caulfield JL, Niles JC, Wishok JS, Tannebaum SR. The chemistry of DNA damage from nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. Mutat Res. 1999;424:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshi MS, Ponthier JL, Lancaster JR. Cellular antioxidant and pro-oxidant actions of nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao CV. Nitric oxide signaling in colon cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res. 2004;555:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim DJ, Shin DH, Kang AB, Nam KT, Park CB, et al. Chemoprevention of colon cancer by Korean food plant components. Mutat Res. 2003;523–524:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sturniolo MT, Dash SR, Deucher A, Rorke EA, Broome AM, et al. A novel tumor suppressor protein promotes keratinocyte terminal differentiation via activation of type I transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48066–48073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ha Mai D, Bondy SC. Pro or anti-oxidant manganese: a suggested mechanism for reconciliation. Neurochem Int. 2004;44:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wlodek L. Beneficial and harmful effects of thiols. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002;54:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shilo S, Aronis A, Komarnitsky R, Tirosh O. Selenite sensitizes mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in vitro and in vivo: a possible mechanism for chemoprotection. Biochem J. 2003;15:283–290. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rorke EA, Jacobberger JW. Transforming growth factor-β1 enhances apoptosis in human papillomavirus type 16-immortalized human ectocervical epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1995;216:65–72. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beninati S, Piacentini M. The transglutaminase family: an overview (minireview article) Amino Acids. 2004;26:367–372. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lentini A, Abbruzzese A, Caraglia M, Marra M, Beninati S. Protein-polyamine conjugation by transglutaminase in cancer cell differentiation (review article) Amino Acids. 2004;26:331–337. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balasubramanian S, Sturniolo MT, Dubyak GR, Eckert RL. Human epidermal keratinocytes undergo (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate differentiation but not apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1100–1108. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]