Abstract

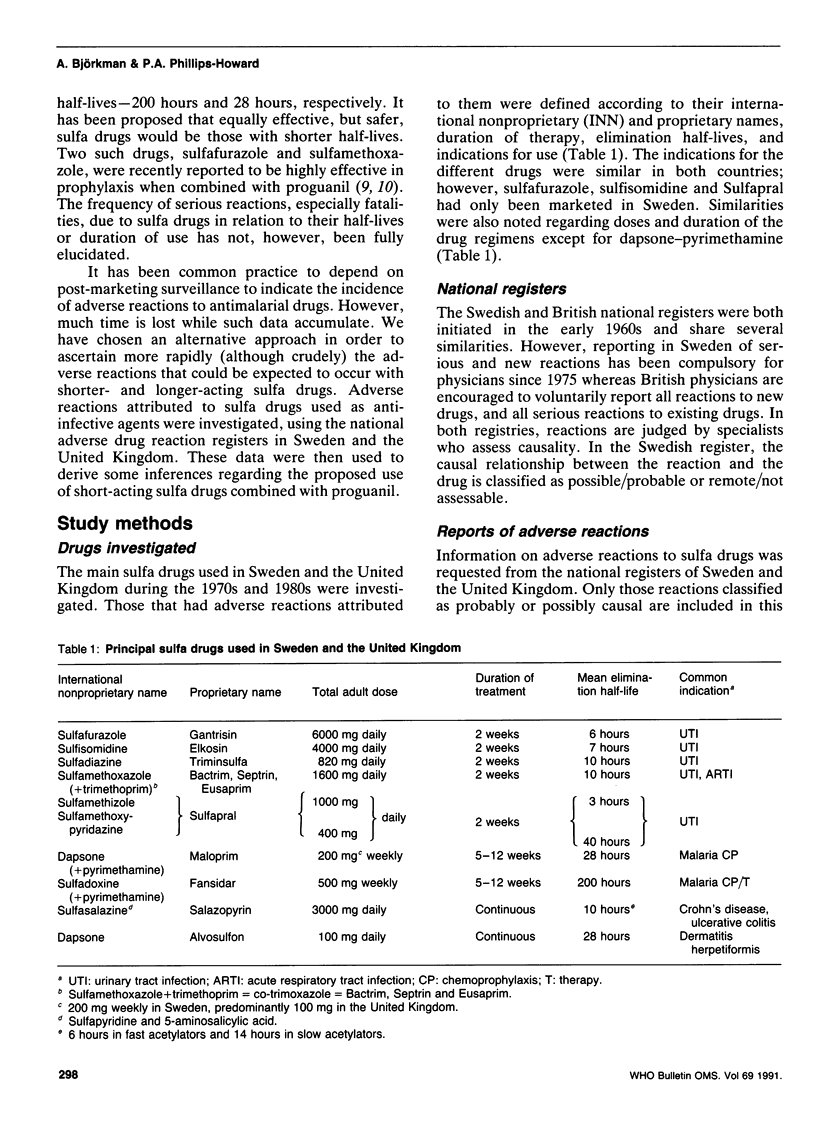

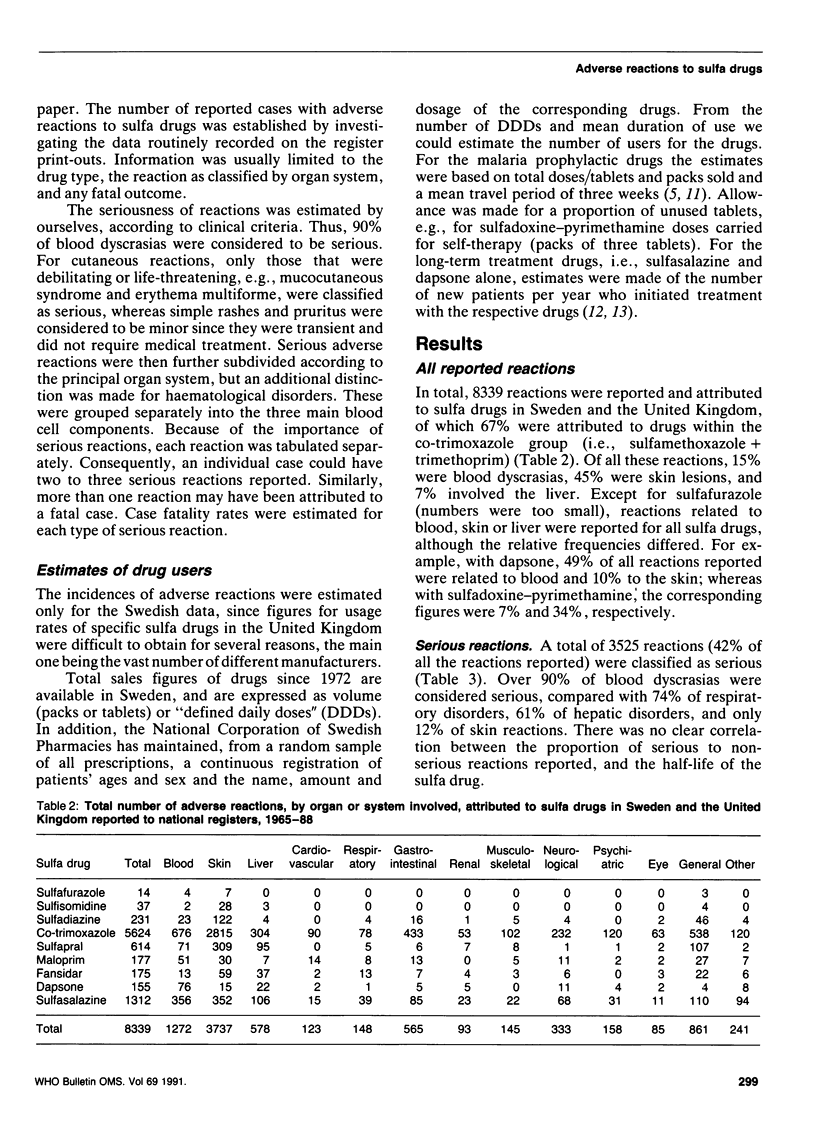

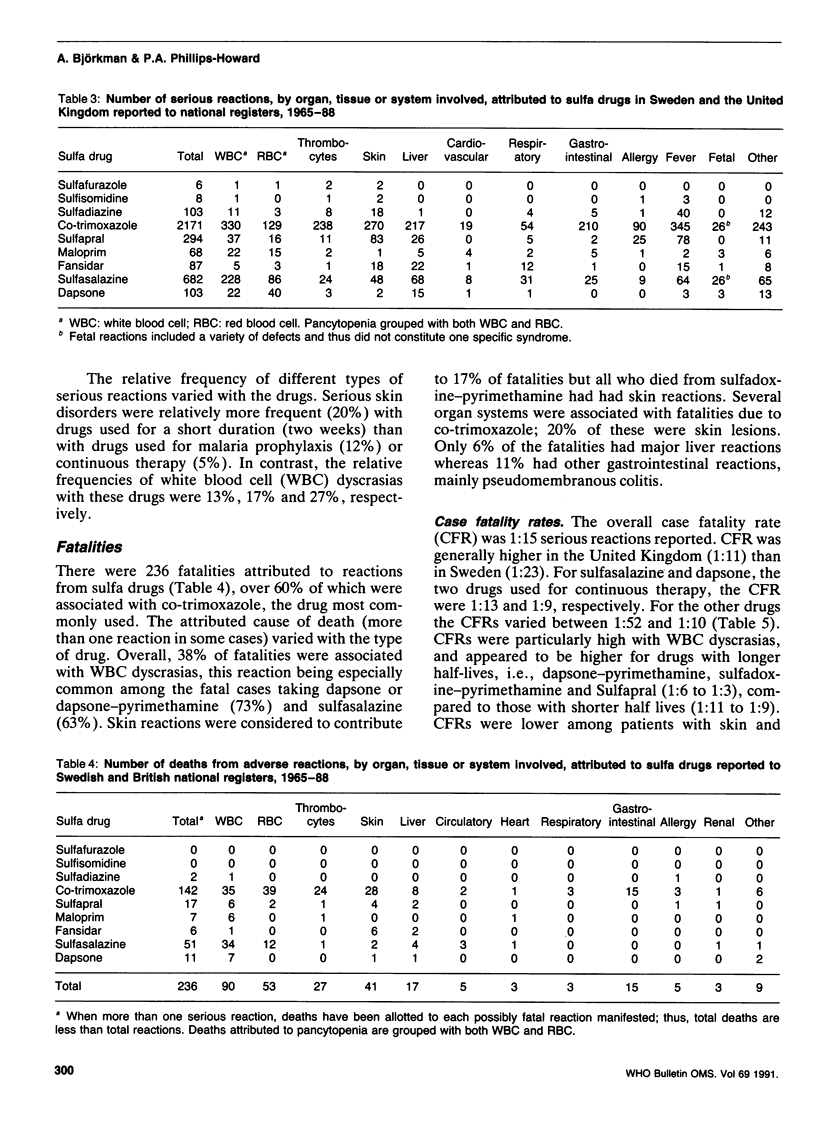

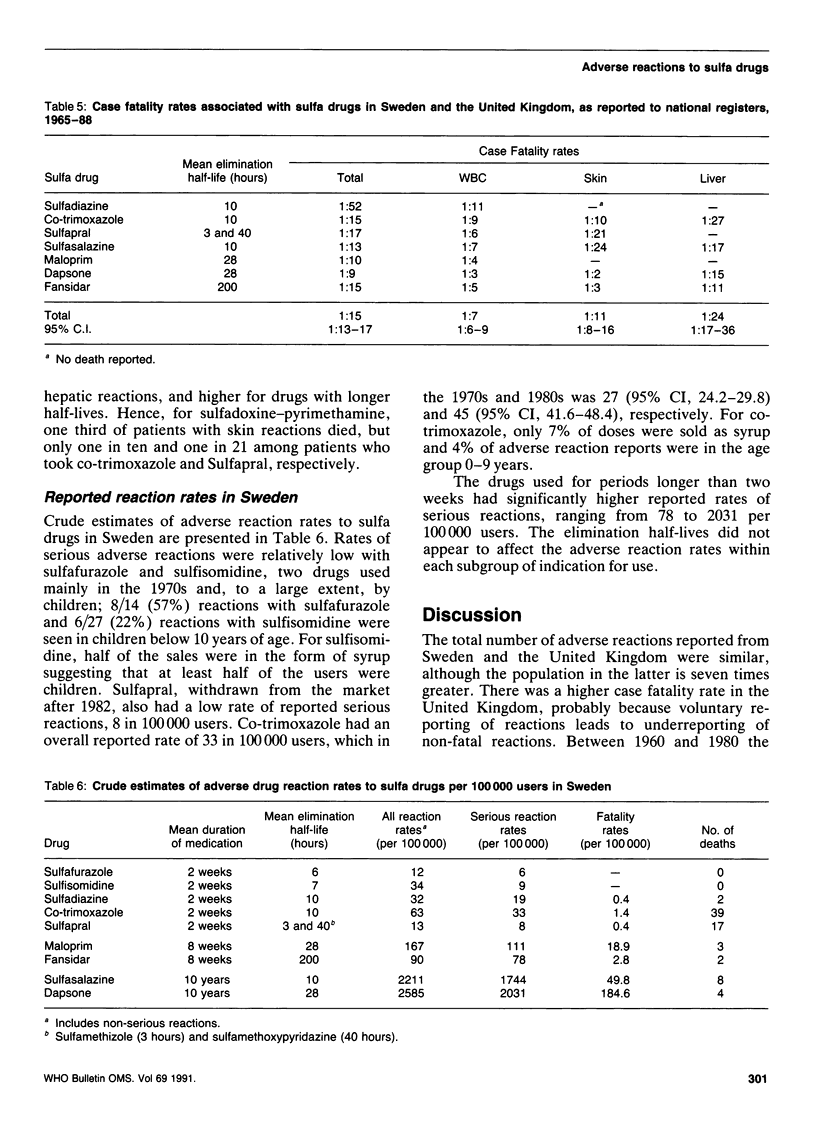

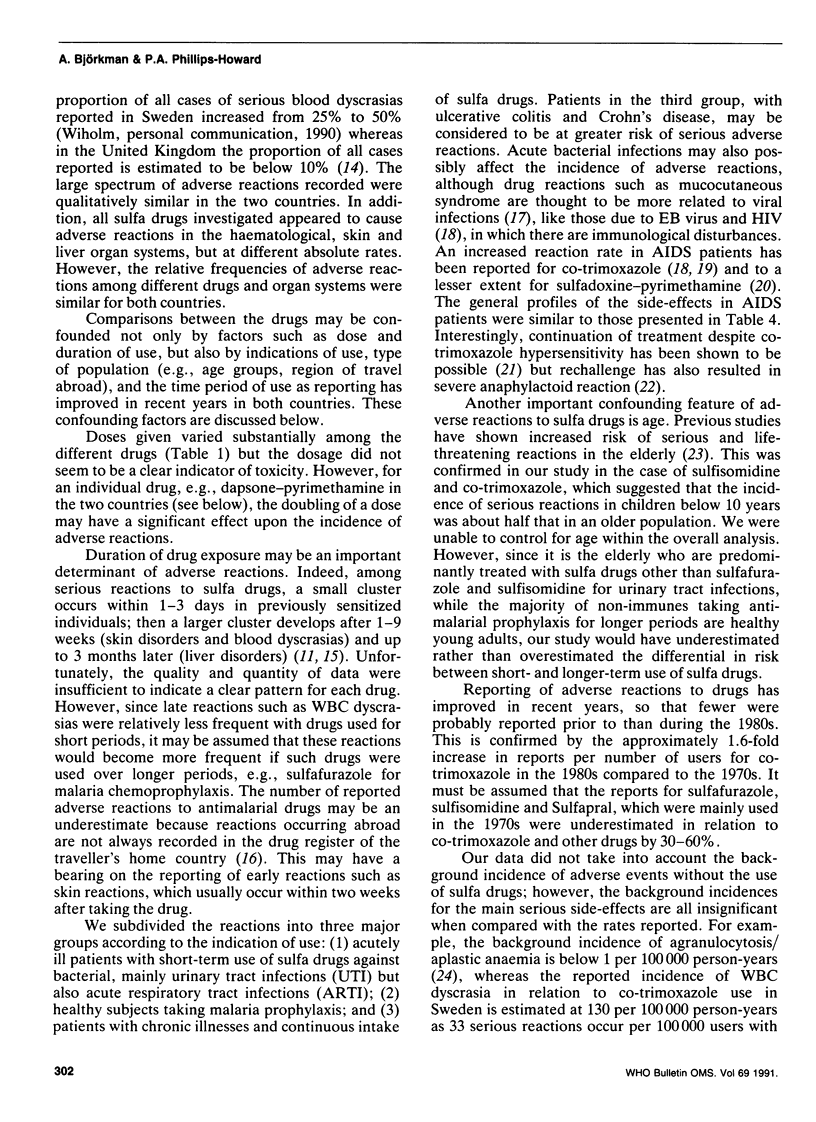

National adverse drug reaction registers in Sweden and the United Kingdom provided data on the type, severity and frequency of reported adverse reactions attributed to sulfa drugs. Reactions to the ten principal drugs were examined in terms of their half-lives and usual indications for use. Of 8339 reactions reported between 1968 and 1988, 1272 (15%) were blood dyscrasias, 3737 (45%) were skin disorders, and 578 (7%) involved the liver. These side-effects occurred with all types of sulfa drugs investigated, although at different relative rates, and 3525 (42%) of them were classified as serious. The overall case fatality rate (CFR) was 1:15 serious reactions, and was highest in patients with white blood cell dyscrasias (1:7). Drugs with longer elimination half-lives had higher CFRs, particularly for fatalities after skin reactions. In Sweden, the estimated incidences of serious reactions were between 9 and 33 per 100,000 short-term users of sulfa drugs (two weeks), between 53 and 111 among those on malaria prophylaxis, and between 1744 and 2031 in patients on continuous therapy. For dapsone, the incidence appeared to increase with higher doses. Our results indicate that sulfa drugs with short elimination half-lives deserve to be considered for use in combination with proguanil or chlorproguanil for malaria chemotherapy and possibly prophylaxis. The smaller risk of adverse reactions associated with lower-dose dapsone suggests that it should also be evaluated as a potentially safe alternative.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Gordin F. M., Simon G. L., Wofsy C. B., Mills J. Adverse reactions to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1984 Apr;100(4):495–499. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-4-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume J. C., Roujeau J. C., Revuz J., Penso D., Touraine R. The culprit drugs in 87 cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell's syndrome). Arch Dermatol. 1987 Sep;123(9):1166–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobacken H., Kastrup W., Nilsson L. A. Incidence and prevalence of dermatitis herpetiformis in western Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64(5):400–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Howard P. A., Behrens R. H., Dunlop J. Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine during presumptive self-therapy of malaria. Lancet. 1989 Sep 30;2(8666):803–804. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90867-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Howard P. A., Bjorkman A. B. Ascertainment of risk of serious adverse reactions associated with chemoprophylactic antimalarial drugs. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68(4):493–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Howard P. A., West L. J. Serious adverse drug reactions to pyrimethamine-sulphadoxine, pyrimethamine-dapsone and to amodiaquine in Britain. J R Soc Med. 1990 Feb;83(2):82–85. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström J. Aetiology of febrile mucocutaneous syndromes with special reference to the provocative role of infections and drugs. Acta Med Scand. 1977 Jan;201(1-2):131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1977.tb15668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]