Abstract

We sought to specifically regulate the binding of human C1q, and thus the activation of the first complement component, via the construction of a single chain antibody variable binding region fragment (scFv) targeting the C1q globular heads. Here we describe details of the construction, expression and evaluation of this scFv, which was derived from a high affinity hybridoma (Qu) specific for the C1q globular heads. The scFv was comprised of the Qu variable-heavy chain domain (VH) linked to the Qu variable-light chain domain (VL) and was termed scFv-QuVHVL. When mixed with either purified C1q or with human serum as a source of C1, scFv-QuVHVL bound to C1q and competitively restricted the interaction of C1q or C1 with immobilized IgG or with IgG1 antibody-coated cells, and prevented the activation of native C1 in human serum as determined by analyses of C1-mediated C4 deposition and fluid phase C4 conversion. However scFv-QuVHVL could be manipulated to become a C1 activator when it was irreversibly immobilized onto microtiter ELISA plates, prior to contact with human serum complement. This functional dichotomy can be a useful tool in selectively elucidating, differentiating, inducing or inhibiting specific roles of human C1q and the classical complement pathway in complement-mediated physiological processes. We project that once fully humanized, fluid phase scFv-QuVHVL could become a useful therapeutic in limiting inadvertent host tissue damage elicited by the classical complement pathway.

Keywords: Complement, Classical Complement Pathway, C1, C1q, C1q globular heads, C4, IgG, scFv, inflammation, inflammatory diseases, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

Despite the effectiveness of complement in clearing immune complexes, chronic complement-mediated inflammation often results in deleterious affects on host tissues. Thus the development of highly specific regulators for selected complement components, most notably at the very initiation of the complement cascade would be advantageous in preventing hard and soft tissue damage in selected immune-complex mediated chronic inflammatory states. The C1 macromolecular complex (Reid and Porter, 1976; Cooper 1985; (Schumaker et al., 1986; Sellar et al., 1991; Kishore and Reid, 1999) is composed of one C1q molecule and two C1r (C1r2) and two C1s (C1s2) molecules. The C1q subcomponent (of C1qr2s2) is a 460 kDa glycoprotein with an umbrella-like structure consisting of 6 A-B chains and 6 C-C chains (Yonemasu and Stroud, 1972). Each chain consists of a short N-terminal region, followed by a collagen-like region and finally each chain becomes part of one of six C1q-terminal globular heads, responsible for binding to exposed segments on the Fc region of antigen-bound IgM or IgG antibodies (Boackle et al., 1979; Kishore and Reid, 1999; Kishore et al., 2003; Gaboriaud et al., 2003).

The best understood function of the C1q subcomponent is its integral non-covalent participation within the macromolecular C1qr2s2 complex in the initiation of the classical pathway of complement. The classical complement pathway begins when several of the globular heads of C1q engage a sufficient number of Fc regions of antibodies bound to antigenic surfaces, leading to C1q conformational changes. These conformational changes induce C1r2 self-activation, which in turn activate the proximate C1s2. Under normal physiological conditions, the rate-limiting factor controlling C1-mediated C4 conversion and C2 activation is the function of C1-inhibitor, as it exquisitely regulates the time allowed for the enzymatic action of C1r2 and C1s2 within the macromolecular C1qr2s2 (Chen and Boackle, 1998; Chen et al., 1998; Boackle et al., 2006). C1 inhibitor molecules form irreversible complexes with activated C1r2 and C1s2 and can separate those inactivated enzymes from tightly fixed C1q (Ziccardi and Cooper, 1979). C1 inhibitor does not directly interact with C1q, thus in vitro, purified C1-inhibitor is unable dislodge an isolated form of bound C1q. However in the presence of neat human serum, C1 inhibitor molecules upon irreversibly binding and inactivating C1r2 and C1s2 may dislodge the entire inactivated C1qr2s2 macromolecular complex when C1 (via C1q) is bound weakly to C1 activators (Chen and Boackle, 1998; Boackle et al., 1998). It is possible that the latter C1 inhibitor mechanism may subsequently disrupt C1qr2s2 in the fluid phase, therein providing a transient source of free fluid phase C1q.

In addition to its role within the macromolecular C1qr2s2 complex, the C1q subcomponent, especially in its isolated (free, fluid phase) form, interacts with an array of non-immunoglobulin substances such as DNA (Uwatoko and Mannik, 1990), serum amyloid P (Bristow and Boackle, 1986; Ying et al., 1993), cardiolipin (Kovacsovics et al., 1985; Boackle et al., 1993), beta-amyloid fibrils (Bradt et al., 1998), decorin (Krumdieck et al., 1992), membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinases (Rozanov et al., 2004) and alpha2beta1 integrins (Edelson et al., 2006).

Furthermore, several C1q-receptors have been identified that upon binding to isolated C1q result in responses, such as reactive oxygen species production by neutrophils (Guan et al., 1994; Goodman et al., 1995; Ruiz et al., 1999), enhancement of phagocytosis by monocytes, macrophages (Bobak et al., 1987) and microglial cells (Webster et al., 2000), and improvement of immunoglobulin production by B-lymphocytes (Daha et al., 1990; Young et al., 1991).

Under certain conditions, isolated C1q appears to suppress LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (Fraser et al., 2007). On the other hand, C1 (via its C1q subcomponent) and the classical pathway may participate in extending the pathology of certain diseases, for example in Alzheimer’s disease via beta-amyloid peptides, which are ligands for C1q that accumulate and may contribute to the pathology of neurodegenerative plaques (Bradt et al., 1998; Selkoe and Schenk 2003; Sarvari et al., 2003); in cardiovascular disease via oxidized low density lipoprotein immune-complexes (Saad et al., 2006); and in type-2 diabetes in regard to possible adipose tissue inflammation that may alter adipocytes causing insulin resistance (Zhang et al., 2007). With regard to adipose tissue inflammation, it is speculated that C1 via its C1q subcomponent fixes to C-reactive protein deposited on adipocytes. In addition, purified C1q binds directly to receptors on endothelial cells and promotes the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1 (van den Berg et al., 1998).

Many of the above reports demonstrate the inflammatory roles of C1 and C1q particularly in non-infectious situations. Thus, the development of substances to control the interaction of C1q with immune complexes are of interest (Bureeva et al., 2007). In particular, highly specific approaches that will block particular regions on C1q such as the C1q globular heads would be highly desirable and is the subject of the present study.

The single chain Fv (scFv) format is widely used to control proteins and enzymes, especially those involved in immune function. Although a relatively small molecule (∼18-25kD), a scFv retains the specificity of the parent antibodies from which it was derived. Currently, specific scFvs are in use in vitro that inhibit proteases such as membrane type serine protease-1, which has been implicated in ovarian and prostate tumor progression (Farady et al., 2007), as well as to study the pleiotropic functions of substances such as IL-13, to better understand their role in immune function (Knackmuss et al., 2007).

Here we report the engineering, purification, characterization and evaluation of a novel scFv consisting of the variable heavy and the variable light domains of a high affinity antibody against C1q globular heads. This engineered scFv enabled the specific control of selected C1q functions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cells and cell culture

The parent hybridoma Qu, that produces antibodies against C1q, was purchased from Quidel (San Diego, CA) and cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biological) and 2mM glutamine (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA). The monoclonal antibody expressed by Qu has been well characterized and its affinity for C1q globular heads described in an earlier publication from our laboratory (Chen et al., 1998). The cancer cell line SK-BR3 was purchased from ATCC and cultured in McCoy’s 5a (ATCC) supplemented with 10% FBS and 2mM glutamine. CHO-S cells were grown in specialized serum-free CD-CHO medium supplemented with glutamine synthetase (GS) supplement (Invitrogen Corp) and 25μM-200μM of methionine sulphoximide (MSX) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

2.2 Complement

Venous blood from healthy donors served as a source of complement and was prepared as previously described (Boackle et al., 1993). Human subjects gave informed consent prior to giving blood. Fresh normal human serum (NHS) was diluted in isotonic barbital-buffered saline pH 7.4 containing 0.15 mM calcium chloride and 1.0 mM magnesium chloride (BBS++).

2.3 Construction of scFv-QuVHVL

2.3.1 Cloning of variable antibody fragments

Total RNA was extracted from the hybridoma, Qu, using RNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed for first strand cDNA synthesis of the variable heavy chain region (QuVH) region and the variable light chain region (QuVL) employing a mixture of primers from a scFv module (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The isolated DNA was subcloned into a TA vector, transformed into a competent E. coli strain TOP10 (Invitrogen). Blue-white screening and ampicillin (Sigma) selection were used to select positive clones from which DNA was extracted and sequenced.

2.3.2 Construction of QuVH-VL

In the construction of scFv-QuVHVL, a specialized cloning vector, pUC-3541, containing a multiple cloning site and a flexible, 15 amino acid (aa) linker consisting of [glycine4 serine]3 ((Gly4Ser)3) was used. Table 1 lists the primers used in the construction of the scFv-QuVHVL. The QuVHFOR and QuVHREV were used to incorporate a SalI site to the 5′ end and a StuI site to the 3′end of QuVH. QuVL was modified using QuVLFOR and QuVLREV adding a BamHI site to the 5′ end and an EcoRI site was added to the 3′end. The two regions were subsequently digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated into the pUC-3541 vector to flank the existing (Gly4Ser)3 linker. The scFv-QuVHVL construct was further modified and inserted into a pEE mammalian expression vector. Using scFvFOR and scFvREV primers, a BstBI site, a Kozak sequence and a secretion signal peptide were incorporated to the 5′ end of the scFv, and to the 3′ end were added six histidines (6xHis), a stop codon and the restriction site PmlI. All primers were generated by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA).

Table I.

Primers used to generate the scFv-QuVHVL construct

| QuVH FOR | 5′-AAGTCGACATGGAGGTGAAGCTGCAGGAGTC-3′ |

| QuVH REV | 5′-ATAGGCCTTGGAG ACGGTGACCGTG-3′ |

| QuVL FOR | 5′-GAGGATCCGAGGTGAAGCTGCAGGA GTC-3′ |

| QuVL REV | 5′-GAGGAATTCTTATGTGATTTCCAGCTTGGTGCCTCC-3′ |

| scFv FOR | 5′-GCTGAGTTCGAAGCCGCCACCATGCCCATGGGGTCTCTGCAACCGCTGGCCACCTTGTACCTGCTGGGGATGCTGGTCGCTTCCGTGCTAGCGGAGGTGAAGC TGCAGGAGTC-3′ |

| scFv REV | 5′-GACTCTCACGTGTTAATGATGATGATGATGATGCCGTTTGATTTCCAG CTTGGTGCCTCCACC-3′ |

2.4 Expression and Isolation of scFv-QuVHVL

2.4.1 Tranfection of tBiAb expression vectors

All transfection reagents were purchased from Invitrogen and used according to manufacturer’s specifications. Briefly, on the day of transfection, CHO-S cells were washed and resuspended in growth medium at 2 × 106 cells/ml. Subsequently, 1 × 106 cells were seeded per well into a 24-well cell culture plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). The plasmid, pEE-QuVHVL, was mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 in OPTI-MEM in the following ratios: 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3. The cells were incubated with the transfection reagents for 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. After 24 hours, each well of cells was diluted 10-20 fold in fresh CD-CHO medium with GS supplement and 25μM MSX. The cells were then plated into 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C, with 5% CO2 for 2-4 weeks with minimal disturbance to allow for selection.

2.4.2 Screening for positive clones

Two methods were used for screening of clones secreting scFv-QuVHVL. Initially ELISA assays were used in a rapid-screening process. In this screening ELISA, an optimally determined dose (1.25μg/ml) of C1q (Quidel) was diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and immobilized for 18 hours at 4°C on microtiter plates (Immulon 1B, Costar, Cambridge, MA), washed with 0.15M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.8 (PBS), and blocked with 2% ultrapure bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) and washed again. Supernatants from the 96-well cell-culture plates were transferred to the C1q-immobilized wells and incubated at RT for 1 hour. After incubation, the plates were washed with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS (TPBS). The plates were probed for 6xHis-tagged proteins using a mouse anti-6xHis monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Serotec, Oxford, UK) preparation in 0.1% BSA-TPBS for 1 hour at RT. The plates were washed again with TPBS and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Jackson Immunologicals, West Grove, PA) preparation in 0.1% ultrapure BSA in TPBS was added. Lastly the plate was washed with TPBS and substrate consisting of 0.1M citrate buffer (pH4.0), 2,2′-azo-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Boeringer Mannheim, Germany) and 3% hydrogen peroxide was added. The plate was read at OD415nm using VMAX Kinetic Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA). In the kinetic ELISA, the initial rates of optical density change per minute in each well were measured and compared.

Positive clones first identified by ELISA were then verified by Western blot analysis as follows. Cell supernatants were mixed with 4x sodium dodecyl sulphate sample buffer (SDS Tris-HCl, 10% glycerol). The samples were then boiled for 5 minutes and applied to a 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel (Biorad). The gel was run in a SDS running buffer (tris-glycine) at 150V constant current for 2 hours. The gel was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Biorad) by electrophoretic blotting at 250 mAmp with constant cooling for 1 hour in blotting buffer with 20% methanol. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk prepared in PBS for 1 hour at RT. The blot was washed with PBS and probed with the previously described anti-6xHis mAb and anti-mouse IgG-HRP preparations. Lastly, substrate consisting of 4-chloro-1-naphthol, methanol, PBS and 0.0125% hydrogen peroxide was added for color development.

2.4.3 Isolation and Purification of 6xHis-tagged proteins secreted by CHO-S cells

Positive clones were transferred into one liter roller bottles (Falcon) and cultured until 250ml of medium had 2×106 cell density. The cell culture supernatants were harvested by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 20 minutes. Ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to 50% saturation, and centrifuged at 3000 × g to spin down precipitated protein. The obtained pellet was dissolved in 20 ml of PBS and dialyzed against three changes of 1.5L of native purification buffer (NPB: 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaPO4, pH 7.8), which also served as the binding-buffer for the subsequent Ni-NTA chromatography. After dialysis, the solution was applied to a 10 ml column containing 2 ml of Ni-NTA resin (Invitrogen). The column was gently agitated at 4°C overnight, and then washed four times with 8 ml NPB. The target protein was eluted from the resin using 8 ml of NPB containing 250 mM imidazole. The eluate was collected in 1 ml fractions and analyzed with SDS-PAGE and Western blot for presence of the 6xHis-tagged scFv-QuVHVL (data not shown). The scFv-QuVHVL was quantified using a BCA Assay from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL).

2.5 Functional Analysis of scFv-QuVHVL

2.5.1 Binding of C1q to immobilized scFv-QuVHVL

The binding of C1q to immobilized scFv-QuVHVL was determined by a sandwich ELISA. Dilutions from 0.25μg/well to 1μg/well of scFv-QuVHVL (in carbonate buffer) were immobilized in triplicate for 18 hours at 4°C onto a 96 well microtiter plate. Human IgG and the parent monoclonal Ab (Qu mAb) were immobilized separately as positive controls. Once immobilized, human IgG forms plastic-bound IgG aggregates that imitate IgG-immune complexes in binding C1q. The washes and blocking were done in the same manner as previously described. Next 0.125μg of C1q in PBS with 0.1% ultrapure BSA, was added to each well and incubated at RT for 1 hour. Subsequently sheep anti-human C1q IgG (Binding Site Inc., Birmingham, UK) was added at RT for 1hr followed by a donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP (Binding Site). Substrate was added and the plates were read at 415nm using the VMAX Kinetic Microplate Reader.

2.5.2 Classical Pathway Activation

Serial dilutions of scFv-QuVHVL or of human IgG (1μg, 0.5μg and 0.25μg in carbonate buffer) were immobilized on microtiter plates overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed three times with 200μl of PBS and blocked with 150μl of 1% ultrapure BSA in PBS. A 1:8 final dilution of fresh NHS in BBS++ was added and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The plates were washed 5x with 200μl/well of TPBS then probed for deposited C4b using sheep anti-human C4. The remainder of the kinetic ELISA procedure was performed in the same manner as described above.

2.5.3 Blocking of C1q binding to Immobilized IgG by fluid-phase scFv-QuVHVL

Serial dilutions of human IgG (1μg/well to 0.25μg/well) in carbonate buffer were immobilized on microtiter plates for 18 hours at 4°C. The immobilized human IgG molecules form surface-bound aggregates that mimic the C1-activating properties of immune complexes. The washes and blocking were done in the same manner as previously described. Next, 1μg of scFv-QuVHVL was incubated with 0.125μg of C1q in PBS with 0.1% BSA on ice for 1 hour. The mixture of scFv-QuVHVL and C1q was then added to the immobilized IgG and incubated for 1 hour at RT. After incubation, the plate was washed 5x with 200μl/well of TPBS, then probed for bound C1q using sheep anti-human C1q followed by donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP. The remainder of the ELISA was carried out in the same manner as described above.

In a second version of the C1q blocking assay, a constant level of human IgG (0.5μg/well) was immobilized on microtiter plates for 18 hours at 4°C in carbonate buffer. The washes and blocking were done in the same manner as previously described. Subsequently, various doses of scFv-QuVHVL ranging from 0.125μg to 4μg were incubated with 0.125μg of C1q in PBS with 0.1% ultrapure BSA on ice for 1 hour. The mixture was then added to the immobilized human IgG and incubated for 1 hour at RT. After incubation, the plate was washed 5x with 200μl/well of TPBS then probed for bound C1q using sheep anti-human C1q followed by donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP. The remainder of the ELISA was carried out in the same manner as described above.

2.5.4 Blocking the Activation of the Classical Pathway

To fix C1 and activate the classical complement pathway, human IgG was immobilized on microtiter plates as described above. Separately, a 1:8 final dilution of fresh NHS in BBS++ was mixed on ice for 30 minutes with 1μg, 0.5μg. 0.25μg or 0.125μg of scFv-QuVHVL in PBS. Dilution volumes of scFv-QuVHVL and of control samples were equalized using PBS. After incubation, the mixtures of NHS with scFv-QuVHVL were added to the microtiter plates, which were covered and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. The plates were washed 5x with 200μl/well of TPBS, then probed for deposited C4b using sheep IgG antibody to human C4. The remainder of the ELISA was carried out in the same manner as described above.

2.5.5 Blocking by scFv-QuVHVL of Fluid Phase C1 Activation

Fluid-phase C1 activation was evaluated by observing the conversion of native C4 to C4b via Western Blot. Doses of scFv-QuVHVL, from 5μg to 1.25μg, were added to 1:8 fresh NHS (final dilution volumes were equalized using PBS) for 1 hour on ice. Next, aggregated human IgG (Agg IgG) at specified levels was added to the samples and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C to promote complement activation. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 4x SDS-loading buffer to the mixtures. The samples were boiled for 5 minutes and applied to a 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel. The running of the gel and blotting were carried out in the same manner as previously described. The blot was probed with sheep anti-human C4, followed by a secondary rabbit anti-sheep IgG-HRP. Substrate was added for color development as described above.

2.5.6 Blocking by scFv-QuVHVL of C1q Binding to Antibody-Coated Human Cells

Flow cytometry was used to demonstrate blocking of C1q binding to Herceptin-coated human cells in vitro. All incubations were conducted on ice unless otherwise noted. The human cells (SKBR-3) were grown to 80% confluence then detached using Versene (Gibco), resuspended to 5×105/100μl in PBS with 0.1% BSA and incubated with 2μg of human IgG1 anti-HER2 mAb (Herceptin) for 1 hour. The cells were washed 3x with 1ml of PBS, 0.1%BSA and resuspended in 100μl PBS, 0.1%BSA. Independently, 1μg of C1q was mixed with 2μg of scFv-QuVHVL for 30 minutes; then the C1q/scFv-QuVHVL mixture was added to the sensitized cells and incubated for 1 hour. Following incubation, the cells were washed 3x and probed with sheep anti-C1q/FITC-labeled Ab (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) The samples were examined via Facscan flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Immunocytometry System, San Diego, CA).

2.5.7 Blocking by scFv-QuVHVL of C1-Mediated C4b Deposition

Blocking of classical pathway activation in fresh human serum was examined by evaluating the levels of C1-mediated C4 deposition on Herceptin-sensitized SKBR-3 cells. Flow cytometry was used to evaluate the level of C4b deposition. All incubations were conducted on ice unless otherwise noted. SKBR-3 cells were sensitized as described above. Fresh normal human serum was diluted 1:4 in BBS++ and was incubated with 2μg of scFv-QuVHVL for 30 minutes. The SKBR-3 cells were washed 3x with 1ml of PBS containing 0.1%BSA and resuspended in 100μl PBS/0.1%BSA. Next 100μl of the NHS/scFv-QuVHVL or NHS/PBS mixture was added to the cells (which resulted in a 1:8 final dilution of NHS) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Following incubation, the complement-treated sensitized cells were washed 3x and probed with goat FITC-labeled anti-C4 (EMD Chemicals, Inc.). The samples were analyzed using Facscan flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Immunocytometry System, San Diego, CA).

3. Results

3.1 Construction and Expression of scFv-QuVHVL

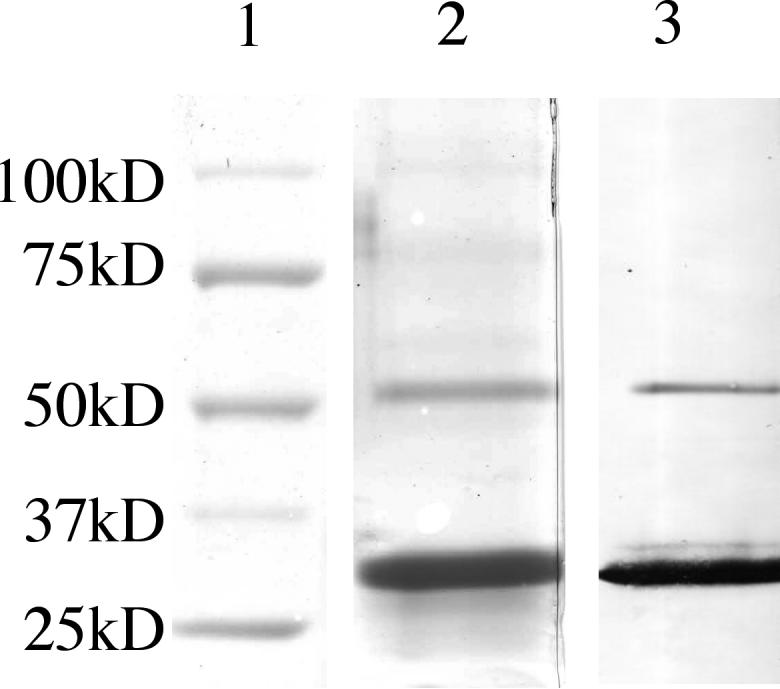

A single chain Fv (scFv-QuVHVL) to C1q globular heads was constructed, expressed and evaluated for regulation of C1 function. The construction included cloning the VL and VH domains from a hybridoma (Qu) producing a high affinity mouse monoclonal IgG1 antibody against human C1q globular heads (Chen et al., 1998). The expression of the scFv-QuVHVL was carried out in CHO-S cells, which were modified for suspension growth in serum-free medium to allow a high cell density growth without potential interference by cross-reactive bovine products (e.g., bovine C1q) in the culture medium. Several positive clones (Q1-Q8) screened by ELISA were analyzed by Western blot to confirm protein expression as well as to discern which clones were producing the highest levels of scFv-QuVHVL (Fig.1). The expressed scFv-QuVHVL had a molecular weight of ∼ 30kDa. Clone Q5 produced the maximal levels of scFv-QuVHVL, and therefore was chosen for large-scale production. From a 250 ml of Q5 culture, approximately 2.5 mg of secreted scFv-QuVHVL was obtained. The final isolated scFv-QuVHVL (the ∼ 30 kD band in Fig. 2, Lanes 2 and 3) was ∼ 95% pure, with a contaminating 6xHis tagged protein of approximately double the size of scFv-QuVHVL, which was presumed to be a dimeric form of scFvQuVHVL (∼ 60 kD band, Fig. 2, Lanes 2 and 3).

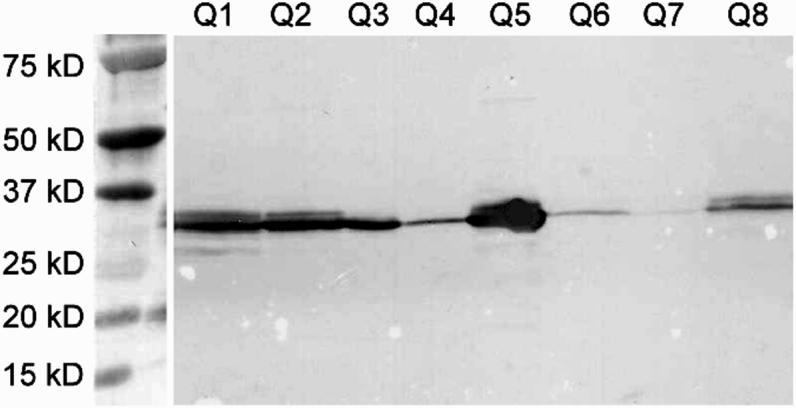

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of eight CHO-S clones demonstrated various levels of scFv-QuVHVL expression. The blot was probed for 6xHis tagged protein with a mouse anti-6xHis mAb followed by goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP. The target protein was a ∼30kD protein. Clone Q5 expressed the highest level of scFv-QuVHVL.

Fig. 2.

After affinity chromatography, the scFv-QuVHVL preparation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot. Lane 1) Molecular weight markers; Lane 2) SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie Blue; Lane 3) Western Blot analysis of 6xHis tagged proteins. The lower band of scFv-QuVHVL contained the 6xHis tagged monomeric scFv-QuVHVL, the upper band (∼5% of the total 6xHis-tagged proteins) had a molecular weight consistent with a dimeric form of scFv-QuVHVL.

3.2 Binding of scFv-QuVHVL to C1q and Classical Pathway Activation

To determine the function of scFv-QuVHVL, the ability of immobilized scFv-QuVHVL to specifically bind C1q was evaluated. Control comparisons for the binding to fluid phase C1q included immobilized (non-specific) human IgG (which forms C1-binding aggregates of IgG when immobilized on the plastic surface of ELISA microtiter plates) and immobilized Qu-mAb (the parent monoclonal antibody from which scFv-QuVHVL was derived). In these studies, serial dilutions from 0.25μg/well to 1.0 μg/well of scFv-QuVHVL, and of the two positive controls (non-specific human IgG and Qu-mAb), were immobilized on ELISA microtiter plates in triplicate. Then a pre-titrated amount of C1q was added and allowed to bind to the immobilized substances for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing to remove unbound C1q, the plate was probed for bound C1q. All three immobilized proteins bound C1q in a dose-dependant manner (Figure 3A). As expected, the bivalent high-affinity parent antibody to C1q globular heads, Qu-mAb, was the most effective with over a 10 fold greater binding than immobilized human IgG or scFv-QuVHVL. However, the levels of C1q binding to immobilized human IgG and scFv-QuVHVL were comparable.

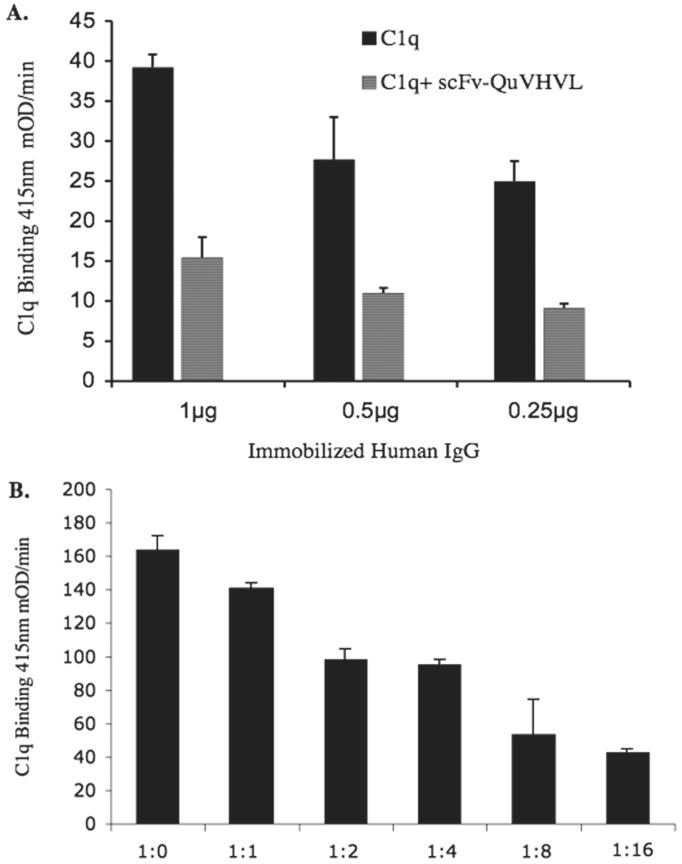

Fig. 3.

Immobilized scFv-QuVHVL was assessed for: A) its ability to bind purified C1q, and; B) when added to fresh human serum to induce C1-mediated C4b deposition. Immobilized scFv-QuVHVL was compared to immobilized human IgG and to the parent Qu-mAb. In two separate ELISA assays (A and B), serial dilutions of the three proteins were separately immobilized, washed, and blocked.

A) Subsequently 0.125μg of purified C1q was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The bound C1q was detected using sheep anti-human C1q followed by donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP.

B) Or NHS (a 1:8 final dilution) was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The deposited C4b was detected using sheep anti-human C4b followed by donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP.

An ELISA was conducted to determine whether immobilized scFv-QuVHVL, upon capturing C1q (located within macromolecular C1 present in fresh NHS) could become an activator of the classical pathway of complement. Serial dilutions of scFv-QuVHVL ranging from 0.25μg to 1μg were immobilized in triplicate. Immobilized human IgG was used for comparison. Fresh normal human serum (at a 1:8 final dilution) in BBS++ was added to the wells and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The plate was washed 5x with 200μl/well of TPBS and probed for deposited C4b. As shown in figure 3B, immobilized scFv-QuVHVL induced C4b deposition in a dose-dependant manner. Irreversibly immobilized human IgG generated a 2-fold to 7-fold higher level of C4b deposition as compared to scFv-QuVHVL. One possible contributing factor to explain this differential phenomenon is that intact human immunoglobulins (in this case irreversibly-immobilized immunoglobulins on the microtiter plates) are excellent acceptors for human C4b (Boackle et al., 2006). It should be stressed that under physiological conditions, after the acceptance of C4b and C3b, antibodies normally are loosened from the reversible interactions with their antigens allowing the departure of those complement-coated antibodies (Boackle et al., 2006). Therefore there was an exaggerated accumulation of C4b on irreversibly immobilized intact human IgG as compared to the immobilized scFv-QuVHVL.

3.3 Blocking of C1q Binding to immobilized human IgG by fluid-phase scFv-QuVHVL

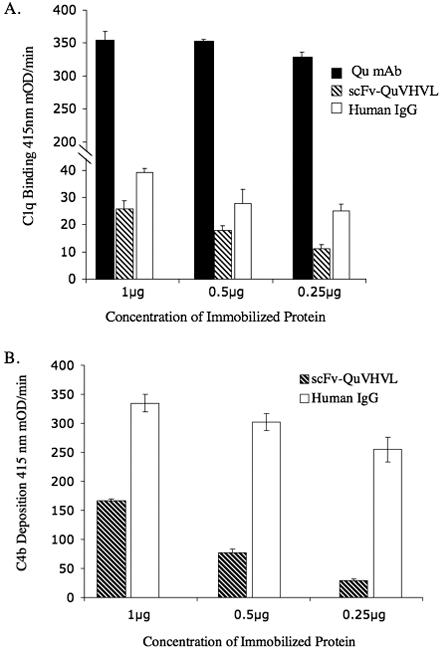

C1q blocking assays were used to determine whether the association of scFv-QuVHVL with C1q (globular heads) was capable of blocking C1q from binding to ligands such as the Fc region of immobilized human IgG. Purified C1q (0.125 μg) was pre-incubated with 1μg of scFv-QuVHVL (1:8 ratio, in the fluid phase) before being added to a microtiter plate containing serial dilutions of immobilized human IgG ranging from 0.25μg/well to 1μg/well. C1q pre-incubated with PBS was used as a control. C1q alone readily bound to immobilized human IgG in a dose dependant manner. However, there was a significant inhibition of binding, up to 63%, when 1μg of scFv-QuVHVL was pre-incubated with 0.125 μg of C1q (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Blocking of C1q binding to immobilized human IgG was demonstrated via ELISA.

A) Serial dilutions of human IgG were immobilized on a microtiter plate as specified. Subsequently 0.125 μg of C1q was mixed with 1μg of scFv-QuVHVL or PBS on ice for 1 hour then applied to the immobilized surface aggregates of human IgG.

B) Blocking of C1q binding was evaluated as a function of the ratio of C1q to scFv-QuVHVL. A constant level of C1q (0.125μg) was incubated with various doses of scFv-QuVHVL (0.125μg - 4μg) for 1 hour on ice. The mixtures were introduced to a constant level of immobilized human IgG (0.5μg/well) and incubated to RT for 1 hour. The levels of bound C1q were detected using sheep anti-human C1q followed by donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP. The ratios C1q to scFv-QuVHVL are shown along the horizontal axis.

Additionally, inhibition of C1q binding was evaluated as a function of various levels of scFv-QuVHVL to a constant level of C1q. In these studies, C1q (0.125 μg) was pre-incubated with doses of scFv-QuVHVL (0.125μg, 0.25μg, 0.5μg, 1μg, 2μg and 4μg) before being added to the microtiter plate containing immobilized human IgG (0.5μg/well). It was observed that the higher the concentration of scFv-QuVHVL, the greater the degree of inhibition of C1q binding to immobilized human IgG, with the maximal inhibition at 74% when the C1q to scFv-QuVHVL ratio was 1:16 (Fig. 4B).

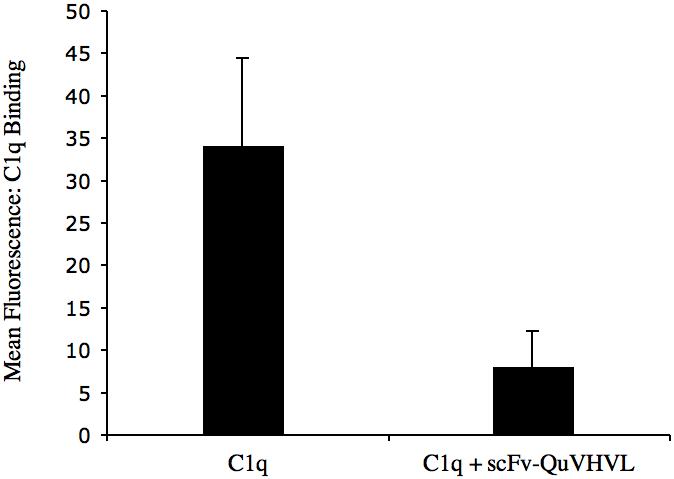

Antigen-antibody complexes formed on cell surfaces provide more physiological Ab conformations, as compared to immunoglobulins immobilized directly to ELISA plate surfaces. Therefore as an antigen, human SKBR-3 cells expressing relatively high levels of Her2/neu were sensitized with a humanized IgG1 antibody (Herceptin) specific for Her2/neu. Human C1q was pre-incubated with scFv-QuVHVL then the mixture was added to the sensitized SKBR-3 cells. After incubation, unbound C1q was removed by washing, and then the cells were evaluated for bound C1q via FACS analysis. As shown in Figure 5, scFv-QuVHVL when pre-incubated with C1q inhibited the binding of C1q to the IgG-coated cells. Thus by binding to the globular heads of C1q, scFv-QuVHVL competitively prevented C1q from binding to IgG-immune complexes on cell surfaces.

Fig. 5.

Blocking of C1q binding to cell-bound IgG1 is demonstrated. SKBR-3 cells (5×105/100μl) were sensitized with 2μg of Herceptin (a humanized anti-HER2 IgG1). In parallel, C1q (0.125 μg) was mixed with 1μg of scFv-QuVHVL (or PBS controls) on ice for 30 minutes, and then applied to the sensitized SKBR-3 cells. After washing, bound C1q was detected using sheep anti-human C1q-FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are the mean ± S.D. of two independent experiments.

3.4 Regulation of C1-mediated C4 Activation by scFv-QuVHVL

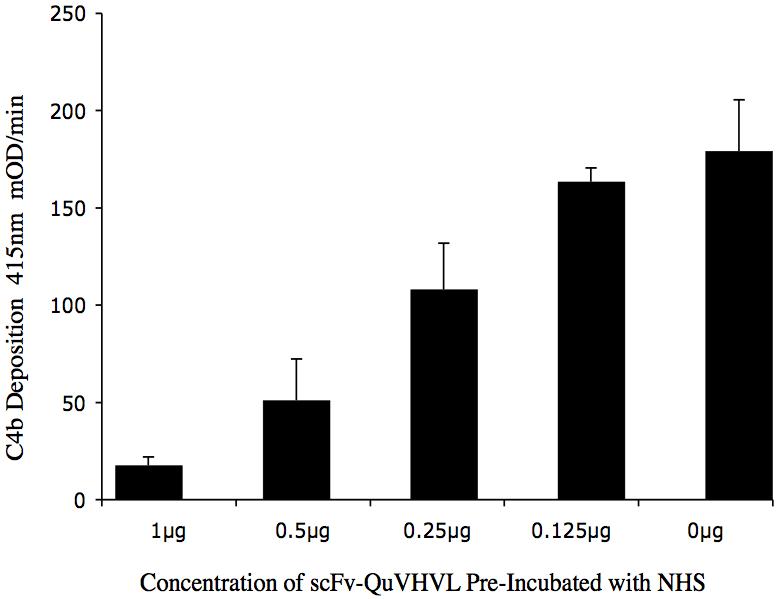

The finding that scFv-QuVHVL blocked C1q from binding to immobilized huIgG or to IgG sensitized cells, suggested a capability for scFv-QuVHVL to block the C1-mediated C4 conversion in human complement. To appraise this capacity, fresh NHS (1:8 final dilution) as a source of complement was pre-incubated with doses of scFv-QuVHVL ranging from 0.125μg to 1μg, then the mixtures along with control NHS without scFv-QuVHVL were added to microtiter plates previously coated with 0.25μg/well of immobilized huIgG. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow C1-medited C4b deposition. After extensive washing, the plates were probed for C4b. As shown in figure 6, prior incubation of human serum with scFv-QuVHVL decreased C4b deposition up to 92% (Table 2). Furthermore, the inhibition of C4b deposition was dose dependant.

Fig. 6.

Dose dependant inhibition of C4b deposition by scFv-QuVHVL is shown. Human IgG (0.25μg/well) was immobilized. Fresh NHS (1:8 final dilution) was incubated with 1μg, 0.5μg, 0.25μg and 0.125μg of scFv-QuVHVL (or PBS) on ice for 30 minutes. The plate was washed and the deposited C4b was detected using sheep anti-C4 antibody followed by donkey anti-sheep IgG-HRP.

Table II.

Inhibition of Human IgG Mediated C4b Deposition

| scFV-QuVHVL | Absorbance 415nm mOD/min | Percent Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| 0 μg | 179.68 | --- |

| 1.0 μg | 17.57 | 92% |

| 0.5 μg | 51.02 | 76% |

| 0.25 μg | 108.04 | 30% |

| 0.13 μg | 163.44 | 19% |

In addition to the ELISA, Western blot analyses were conducted to further demonstrate the ability of scFv-QuVHVL to block C1-mediated C4 conversion. Dilutions of scFv-QuVHVL were mixed with NHS (1:4 final serum dilution) and allowed to mix for 1 hour on ice. Subsequently, one of three different doses of Agg IgG, were added to the mixture and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. The samples were run on SDS-PAGE gels, transblotted and probed for C4. In positive controls, 5μg of Agg IgG caused a complete conversion of C4 (∼250kD) to C4b (∼150kD), whereas, 2.5μg and 1.25μg of Agg IgG caused less C4 conversion, as a proportion of intact C4 remained (Fig. 7). In comparison, the addition of 5μg of scFv-QuVHVL to 100μl of 1:4 diluted NHS, significantly blocked C1-mediated C4 conversion by 5μg of Agg IgG. Furthermore, the inhibition of C1-mediated C4 conversion by scFv-QuVHVL was dose dependant; with 2.5μg of scFv-QuVHVL allowing only a slight amount of C4 conversion and 1.25μg of scFv-QuVHVL not having much effect. Taken together the results indicated that in the fluid phase, scFv-QuVHVL occupied sites on the C1q globular heads, blocked C1 from binding to Agg IgG and thus prevented the C1 activation needed for C1-mediated C4 conversion.

Fig. 7.

Fluid phase inhibition of Agg IgG-C1-mediated C4 conversion by scFv-QuVHVL was evaluated by Western blot analyses. Specified doses of heat-aggregated human IgG (Agg IgG) served to activate C1-mediated C4 conversion to C4b. Serial dilutions of Agg IgG were incubated with NHS that had been mixed with scFv-QuVHVL (or PBS) on ice for 30 minutes. NHS controls with no activating or blocking agents were included for comparison.

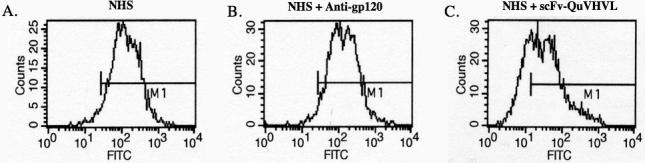

Next, an evaluation was made of the inhibition of C4b deposition on sensitized cells by scFv-QuVHVL. In these studies, HER2 positive SKBR-3 cells were sensitized with 2μg of human IgG1 antibodies (Herceptin). Unbound IgG antibodies were removed by washing and the cells were incubated with NHS pre-mixed with 4μg of scFv-QuVHVL or controls pre-mixed with PBS. As a negative control, NHS was pre-incubated with an irrelevant mAb, anti-gp120. The mixtures were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, and then probed for C4b via FACS analysis. Sensitized SKBR-3 cells activated C1 as determined by C4b deposition, however, when NHS was first mixed with scFv-QuVHVL, C4b deposition was significantly decreased, yielding a 65% inhibition of C4b deposition when compared to the positive controls (Fig. 8). Therefore, scFv-QuVHVL was capable of binding C1q in NHS and inhibiting classical complement pathway activation.

Fig. 8.

The scFv-QuVHVL blocked C1-mediated C4b deposition on human IgG1-coated SKBR-3 cells. The SKBR-3 cells (5×105/100μl) were sensitized with 2μg of Herceptin. Fresh NHS (1:4 final dilution) was mixed with 1μg of scFv-QuVHVL (or PBS) on ice for 1 hour then applied to the sensitized SKBR-3 cells. After washing, deposited C4b was probed using sheep anti-human C4-FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry.

The results when taken together indicated that the scFv-QuVHVL in binding to the globular heads of C1q (purified C1q as well as to C1q within the C1qr2s2 complex within NHS) inhibited C1q interactions with the Fc regions of immobilized human IgG and antigen-bound IgG1. Furthermore, the competitive inhibition exerted by scFv-QuVHVL on C1q blocked C1-mediated C4 deposition and C4 conversion, and the participation of C1 in antigen-antibody activation of the classical pathway of the human complement system.

4. Discussion

The classical complement pathway is a cascading system, which during its progressing activation from C1 through C9 amplifies the number of sequentially involved complement components. Thus increased control on the first component of the cascade, C1 via its C1q subcomponent has a profound consequential effect on the activation of subsequent components.

The engineered scFv-QuVHVL described here consisted of the light and heavy variable chain domains derived from a hybridoma (Qu) producing a high affinity mAb (Qu-mAb) against the C1q globular heads. The C1q globular heads are required for the C1qr2s2 to interact with immune complexes and initiate the classical complement pathway. The goal of blocking the function of the C1q globular heads without inadvertently activating C1 was accomplished using our engineered scFv-QuVHVL. The VH and VL of the scFv-QuVHVL were joined by a flexible (Gly4Ser)3 linker that allowed the two variable domains to fold and associate to form a single binding site for a globular head domain of C1q. A poly-histidine tag was included in the construct to allow for ease of purification and detection. A mammalian expression system was used to express the scFv-QuVHVL to help ensure correct folding and post-translational modification (Gething and Sambrook, 1992). A high-producing clone was utilized to express the scFv-QuVHVL, which had a molecular weight of approximately 30kDa.

In addition to the desired scFv-QuVHVL, a poly-histidine tagged protein of approximately 60 kDa was present on the Western blots that were used to screen the clones for scFv-QuVHVL; however, the concentration of the 60 kD protein at this stage in the procedure was too faint to be satisfactorily photographed (Fig. 1). After affinity chromatography, the concentration of the poly-histidine tagged proteins increased and the faint band became more evident (Fig. 2). The 60 kDa protein may be a dimeric form of the desired 30 kD scFv-QuVHVL. Nonetheless, as seen in figure 7, when the preparation of scFv-QuVHVL was added to NHS, up to a concentration of 10μg/100μl, there was no significant C4 conversion above background, indicating that the contaminating 60 kDa protein was either non-functional or its low levels were blocked by the competing scFv-QuVHVL.

The avidity of scFv-QuVHVL, which is monovalent (for a single C1q globular head) was lower than its bivalent intact monoclonal antibody parent Qu-mAb, which can simultaneously bind two different globular heads within a single C1q molecule. It is well known that bivalency enhances affinity well beyond a two-fold increase over a monovalent molecule of the same specificity (Kubetzko et al., 2006). Our previous studies using the intact fluid-phase monoclonal antibody Qu-mAb resulted in the activation of complement (Chen et al., 1998), making the intact antibody unusable in situations where controlling C1 activation was desired. This fluid-phase C1 activation was caused by the pair of Fab binding sites on each Qu-mAb molecule that simultaneously cross-linked two globular heads on one C1q molecule. This cross-linking induced the conformational changes in C1q that lead to the autoactivation of its serine proteases C1r2, which in turn activated the C1s2 molecules, thus causing classical pathway initiation.

The avidity of scFv-QuVHVL for human C1q was comparable to that of human IgG for C1q. Indeed, fluid phase binding of scFv-QuVHVL to C1q was sufficient to prevent the interaction of C1q with immobilized (surface aggregates of) human IgG. This finding indicated that scFv-QuVHVL was useful in controlling C1 binding and activation. To further test this hypothesis under physiological conditions, fresh NHS as a source of complement was employed. When scFv-QuVHVL was mixed with fresh NHS, scFv-QuVHVL was able to bind C1q in serum and inhibit the initiation of the classical pathway of complement by immobilized surface aggregates of IgG (Fig.6) and by heat-aggregated IgG (Fig.7). Lastly, C1-mediated C4b deposition was prevented on SKBR-3 cells, which were sensitized with specific human IgG1 antibodies (Fig.8). Thus in the future, there may be a possible use for scFv-QuVHVL or its humanized derivative in limiting complement-mediated damage to autoantibody-coated human cells. From our results, we concluded that scFv-QuVHVL bound to individual globular heads of C1q in a manner that competitively inhibited the interaction of C1qr2s2 with the Fc region of IgG1-antigen complexes and subsequently prevented activation of the classical pathway of complement.

Although the lack of an Fc region in scFv-QuVHVL would decrease its half-life in vivo, this time-restriction may be useful in selectively administering protection to affected tissues and organs (e.g., being coated with specific autoantibodies), without a long-term disabling of the classical complement pathway. There are several potential uses for cocktails of complement regulators that could incorporate scFv-QuVHVL. For example, during myocardial infarction, blockage of critical heart capillaries by leukocyte aggregates may extend cardiac damage. Cardiolipin released from within the damaged heart tissues may directly activate C1 and therein exaggerate the complement activation being induced by the released tissue proteases in the generation of C5a. Similarly, a tighter control over complement activation together with a sequestration of generated complement fragments following stroke may reduce complement-mediated neuronal injury.

Once thought to be important only in the complement system, recent findings have shed light on the diverse and integral participation of C1q in many other immunological functions (e.g., the role of C1q-receptors). Additionally, implications for the role of C1q in several diseases ranging from insulin-resistant-diabetes to Alzheimer’s disease indicate the need for continued study of ways to control C1q functions.

In conclusion, the monovalent fluid-phase scFv-QuVHVL against the globular head region of C1q effectively blocked C1q from associating with human IgG1 antibody-antigen complexes, with immobilized IgG and with heat-aggregated IgG. The scFv-QuVHVL-mediated blocking of C1q binding (to the above forms of IgG) restricted C1 activation as determined by the prevention of C1-mediated C4 conversion/deposition, therein restricting the initiation of the classical complement pathway and the potential of this pathway to contribute to the generation of inflammatory mediators.

In the fluid phase, the scFv-QuVHVL bound in a monovalent manner to individual C1q globular heads, thus there was no cross-linking of the globular heads and C1 activation was avoided. However, if the scFv-QuVHVL molecules were first irreversibly immobilized on ELISA microtiter plates, whereby they could simultaneously engage (cross-link) several globular heads of single C1q molecules and cause the required conformational changes in C1q, the scFv-QuVHVL became an effective C1qr2s2 activator (Fig. 3b). This dichotomy of scFv-QuVHVL function may be useful in differentiating the participation of the classical pathway (e.g., versus the lectin pathway or alternative pathway) when examining various complement activators.

More interestingly, the scFv-QuVHVL or its derivative when fully humanized may become a useful therapeutic tool, especially when used together with exogenously supplied recombinant C1-inhibitor (Padilla et al., 2007; Széplaki et al., 2007) and C4b- and C3b-scavenging (non-specific) intravenous immunoglobulin preparations (Boackle et al,. 2006; Arumugam et al. 2007), designed to control complement-mediated assaults on host tissues in circumstances such as organ transplants, antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases, extended cardiac damage following myocardial infarctions and neuronal cell death following stroke. In each of these non-infectious situations, a timely and extraordinary control over the complement system could prevent direct and inadvertent damage to host tissues and organs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, AI069957 (to RJB) and from the Department of Defense, Breast Cancer Program, DAMD17-02-1-0564 (to RJB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arumugam TV, Tang SC, Lathia JD, Cheng A, Mughal MR, Chigurupati S, Magnus T, Chan SL, Jo DG, Ouyang X, Fairlie DP, Granger DN, Vortmeyer A, Basta M, Mattson MP. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) protects the brain against experimental stroke by preventing complement-mediated neuronal cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14104–14109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700506104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boackle RJ, Connor MH, Vesely J. High molecular weight non-immunoglobulin salivary agglutinins (NIA) bind C1Q globular heads and have the potential to activate the first complement component. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90059-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boackle RJ, Johnson BJ, Caughman GB. An IgG primary sequence exposure theory for complement activation using synthetic peptides. Nature. 1979;282:742–743. doi: 10.1038/282742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boackle RJ, Nguyen QL, Leite RS, Yang X, Vesely J. Complement-coated antibody-transfer (CCAT); Serum IgA1 antibodies intercept and transport C4 and C3 fragments and preserve IgG1 deployment (PGD) Mol. Immunology. 2006;43:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobak DA, Gaither TA, Frank MM, Tenner AJ. Modulation of FcR function by complement: subcomponent C1q enhances the phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized targets by human monocytes and culture-derived macrophages. J Immunol. 1987;138:1150–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradt BM, Kolb WP, Cooper NR. Complement-dependent proinflammatory properties of the Alzheimer’s disease beta-peptide. J Exp Med. 1998;188:431–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow CL, Boackle RJ. Evidence for the binding of human serum amyloid P component to Clq and Fab gamma. Mol Immunol. 1986;23:1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureeva S, Andia-Pravdivy J, Symon A, Bichucher A, Moskaleva V, Popenko V, Shpak A, Shvets V, Kozlov L, Kaplun A. Selective inhibition of the interaction of C1q with immunoglobulins and the classical pathway of complement activation by steroids and triterpenoids sulfates. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:3489–3498. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Boackle RJ. A newly discovered function for C1 inhibitor, removal of the entire C1qr2s2 complex from immobilized human IgG subclasses. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;87:68–74. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Lam CF, Boackle RJ. C1 inhibitor removes the entire C1qr2s2 complex from anti-C1Q monoclonal antibodies with low binding affinities. Immunology. 1998;95:648–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N. The classical complement pathway: activation and regulation of the first complement component. Advances in Immunology. 1985:65. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daha MR, Klar N, Hoekzema R, van Es LA. Enhanced Ig production by human peripheral lymphocytes induced by aggregated C1q. J Immunol. 1990;144:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson BT, Stricker TP, Li Z, Dickeson SK, Shepherd VL, Santoro SA, Zutter MM. Novel collectin/C1q receptor mediates mast cell activation and innate immunity. Blood. 2006;107:143–150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farady CJ, Sun J, Darragh MR, Miller SM, Craik CS. The mechanism of inhibition of antibody-based inhibitors of membrane-type serine protease 1 (MT-SP1) J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MI, Kawas CH, Troncoso JC, Tenner AJ. Neuronal localization of C1q in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004a;15:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MI, Zhou J, Botto M, Tenner AJ. Absence of C1q leads to less neuropathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2004b;24:6457–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0901-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DA, Arora M, Bohlson SS, Lozano E, Tenner AJ. Generation of inhibitory NFkappaB complexes and phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein correlates with the anti-inflammatory activity of complement protein C1q in human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7360–7367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriaud C, Juanhuix J, Gruez A, Lacroix M, Darnault C, Pignol D, Verger D, FontecillaCamps JC, Arlaud GJ. The crystal structure of the globular head of complement protein C1q provides a basis for its versatile recognition properties. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46974–46982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething MJ, Sambrook J. Protein folding in the cell. Nature. 1992;355:33–45. doi: 10.1038/355033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JL, Uemura E, Cunnick JE. Microglial release of nitric oxide by the synergistic action of beta-amyloid and IFN-gamma. Brain Res. 1995;692:207–14. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00646-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan E, Robinson SL, Goodman EB, Tenner AJ. Cell-surface protein identified on phagocytic cells modulates the C1q-mediated enhancement of phagocytosis. J Immunol. 1994;152:4005–4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore U, Gupta SK, Perdikoulis MV, Kojouharova MS, Urban BC, Reid KB. Modular organization of the carboxyl-terminal, globular head region of human C1q A, B, and C chains. J Immunol. 2003;171:812–820. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore U, Reid KB. Modular organization of proteins containing C1q-like globular domain. Immunopharmacology. 1999;42:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackmuss S, Krause S, Engel K, Reusch U, Virchow JC, Mueller T, Kraich M, Little M, Luttmann W, Friedrich K. Specific inhibition of interleukin-13 activity by a recombinant human single-chain immunoglobulin domain directed against the IL-13 receptor alpha1 chain. Biol Chem. 2007;388:325–330. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacsovics T, Tschopp J, Kress A, Isliker H. Antibody-independent activation of C1, the first component of complement, by cardiolipin. J Immunol. 1985;135:2695–2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Possible role of flanking nucleotides in recognition of the AUG initiator codon by eukaryotic ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:5233–5252. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.20.5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumdieck R, Hook M, Rosenberg LC, Volanakis JE. The proteoglycan decorin binds C1q and inhibits the activity of the C1 complex. J Immunol. 1992;149:3695–3701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla ND, van Vliet AK, Schoots IG, Seron MV, Maas MA, Peltenburg EE, de Vries A, Niessen HW, Hack CE, van Gulik TM. C-reactive protein and natural IgM antibodies are activators of complement in a rat model of intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. Surgery. 2007;142:722–733. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasinetti GM, Tocco G, Sakhi S, Musleh WD, DeSimoni MG, Mascarucci P, Schreiber S, Baudry M, Finch CE. Hereditary deficiencies in complement C5 are associated with intensified neurodegenerative responses that implicate new roles for the C-system in neuronal and astrocytic functions. Neurobiol Dis. 1996;3:197–204. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RR, Reid KB. Activation of the complement system by antibody-antigen complexes: the classical pathway. Adv Protein Chem. 1979;33:1–71. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60458-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KB, Porter RR. Subunit composition and structure of subcomponent C1q of the first component of human complement. Biochem J. 1976;155:19–23. doi: 10.1042/bj1550019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanov DV, Savinov AY, Golubkov VS, Postnova TI, Remacle A, Tomlinson S, Strongin AY. Cellular membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) cleaves C3b, an essential component of the complement system. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46551–46557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz S, Henschen-Edman AH, Tenner AJ. Localization of the site on the complement component C1q required for the stimulation of neutrophil superoxide production. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30627–30634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad AF, Virella G, Chassereau C, Boackle RJ, Lopes-Virella MF. Autoimmune OxLDL immune-complexes activate the classical pathway of complement and induce cytokine production by mono mac 6 cells and primary human macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1975–1983. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600064-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvari M, Vago I, Weber CS, Nagy J, Gal P, Mak M, Kosa JP, Zavodszky P, Pazmany T. Inhibition of C1q-beta-amyloid binding protects hippocampal cells against complement mediated toxicity. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:12–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker VN, Hanson DC, Kilchherr E, Phillips ML, Poon PH. A molecular mechanism for the activation of the first component of complement by immune complexes. Mol Immunol. 1986;23:557–565. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Schenk D. Alzheimer’s disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:545–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellar G, Cockburn D, Reid KB. Localization of the gene cluster encoding the A, B, and C chains of human C1q to 1p34.1-1p36.3. Immunogenetics. 1992;35:3. doi: 10.1007/BF00185116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Széplaki G, Varga L, Laki J, Dósa E, Rugonfalvi-Kiss S, Madsen HO, Prohászka Z, Kocsis A, Gál P, Szabó A, Acsády G, Karádi I, Selmeci L, Garred P, Füst G, Entz L. Low c1-inhibitor levels predict early restenosis after eversion carotid endarterectomy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2756–2762. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.146860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uwatoko S, Mannik M. The location of binding sites on C1q for DNA. J Immunol. 1990;144:3484–3488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg RH, Faber-Krol MC, Sim RB, Daha MR. The first subcomponent of complement, C1q, triggers the production of IL-8, IL-6, and monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1 by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6924–6930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster SD, Yang AJ, Margol L, Garzon-Rodriguez W, Glabe CG, Tenner AJ. Complement component C1q modulates the phagocytosis of Abeta by microglia. Exp Neurol. 2000;161:127–138. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Mucke L. Inflammation in neurodegenerative disease--a double-edged sword. Neuron. 2002;35:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying SC, Gewurz AT, Jiang H, Gewurz H. Human serum amyloid P component oligomers bind and activate the classical complement pathway via residues 14-26 and 76-92 of the A chain collagen-like region of C1q. J Immunol. 1993;150:169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonemasu K, Stroud RM. Structural studies on human Clq: non-covalent and covalent subunits. Immunochemistry. 1972;9:545–554. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(72)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KR, Jr., Ambrus JL, Jr., Malbran A, Fauci AS, Tenner AJ. Complement subcomponent C1q stimulates Ig production by human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1991;146:3356–3364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wright W, Bernlohr DA, Cushman SW, Chen X. Alterations of the classic pathway of complement in adipose tissue of obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1433–1440. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00664.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziccardi RJ, Cooper NR. Active disassembly of the first complement component, C-1, by C-1 inactivator. J Immunol. 1979;123:788–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]