Abstract

Mutations in the human DNA mismatch repair (MMR) gene MLH1 are associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome, HNPCC) and a significant proportion of sporadic colorectal cancer. The inactivation of MLH1 results in the accumulation of somatic mutations in the genome of tumor cells and resistance to the genotoxic effects of a variety of DNA damaging agents. To study the effect of MLH1 missense mutations on cancer susceptibility, we generated a mouse line carrying the recurrent Mlh1G67R mutation that is located in one of the ATP-binding domains of Mlh1. Although the Mlh1G67R mutation resulted in DNA repair deficiency in homozygous mutant mice, it did not affect the MMR-mediated cellular response to DNA damage, including the apoptotic response of epithelial cells in the intestinal mucosa to cisplatin, which was defective in Mlh1−/− mice but remained normal in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice. Similar to Mlh1−/− mice, Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant mice displayed a strong cancer predisposition phenotype. However, in contrast to Mlh1−/− mice, Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant mice developed significantly fewer intestinal tumors, indicating that Mlh1 missense mutations can affect MMR tumor suppressor functions in a tissue-specific manner. In addition, Mlh1G67R/G67R mice were sterile because of the inability of the mutant Mlh1G67R protein to interact with meiotic chromosomes at pachynema, demonstrating that the ATPase activity of Mlh1 is essential for fertility in mammals.

Keywords: DNA damage response, HNPCC, Meiosis, Mlh1, MMR

Mutations in the human DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes MSH2, MSH6 (MutS homolog), and MLH1 (MutL homolog 1) are the cause of the majority of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome, HNPCC) cases and also a significant number of sporadic cancers (1, 2). The DNA MMR system plays a critical role in the maintenance of genome integrity and functions in the postreplicative repair of base substitution mutations as well as small insertions/deletions (IDLs) caused by erroneous replication (3). In addition, studies in yeast and mice indicate that several of the MMR proteins have essential meiotic functions (4, 5). In eukaryotic cells, MMR is initiated by subsets of MutS homologs (MSH) that form heterodimeric complexes: MSH2–MSH6 (MutSα) and MSH2–MSH3 (MutSβ). The MutSα complex recognizes base–base mispairs and single-base IDLs, whereas the MutSβ complex detects single-base and larger IDLs to initiate the repair process. As a result of mismatch recognition, the MutSα and MutSβ complexes undergo ATP-hydrolysis-dependent conformational transitions and recruit a heterodimeric complex of the MutL homologs MLH1 and PMS2 (MutLα). This interaction between MutS and the MutL complexes is essential for the activation of subsequent MMR steps, i.e., the excision of the mispairs and IDLs and the resynthesis of the excised DNA strand (6–8). Similar to MutS complexes, the mediation of repair excision and resynthesis by MutLα requires ATP binding and hydrolysis (9–11).

In addition to repairing mismatched bases, MMR also contributes to genome stability by stimulating DNA damage-induced apoptosis as part of the cytotoxic response to DNA-damaging agents. Although MMR-proficient cells respond to exposure to DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin by signaling cell cycle arrest at the G2 checkpoint followed by apoptosis, MMR-deficient human tumor cells are defective in this response (8, 12, 13). As a result, they display increased resistance to the genotoxic effects of DNA damage-inducing agents. It has been proposed that both the DNA repair and DNA damage-response functions of MMR are important for the suppression of tumorigenesis. On the one hand, defects in MMR are associated with an increased mutator phenotype, resulting in the accumulation of mutations in tumor-suppressor genes and oncogenes and leading to the initiation of tumorigenesis (14, 15). Alternatively, defects in the MMR-dependent DNA damage response could lead to a failure in clearing DNA damage-bearing cells, which may confer a selective advantage in tumor cells (13, 16, 17). Consistent with this notion, Msh2G674A and Msh6T1217D mutant mice, which carry separation of function mutations that inactivate DNA repair but leave the DNA damage-response function intact, have delayed tumor onset compared with Msh2−/− and Msh6−/− mice, which are defective in both MMR functions (18, 19).

Although the majority of MMR mutations found in Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) patients are frameshift or nonsense mutations that result in an inactive protein, a significant number of MMR mutations are missense mutations [>25% of MSH2 or MLH1 mutations and >45% of MSH6 mutations (20)]. The impact of these missense mutations on the individual MMR functions and their significance for cancer predisposition often remain uncertain. The generation and analysis of mouse lines with MMR point mutations that model Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) mutations provides the opportunity to determine their impact on DNA repair and DNA damage response on the organismal level and assess their impact on carcinogenesis. Here, we report on a knockin mouse line with the first missense mutation in a MutL homolog. This mouse line carries a germ-line mutation that models the recurrent MLH1G67R variant found in several Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) families from different countries (1). Patients carrying the MLH1G67R mutation develop colorectal cancers that are characterized by microsatellite instability (MSI) (21). Consistent with the cancer phenotype in these Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) patients, Mlh1G67R/G67R mice display a strong cancer phenotype. However, in contrast to Mlh1−/− mice, the tumor incidence in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice is significantly different, with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal tumors. This change appears to be caused by the different effects the Mlh1G67R mutation exerts on the DNA repair and damage-response functions in the intestinal mucosa. In addition, the Mlh1G67R mutation causes infertility in both male and female mice that is caused by the inability of the mutant Mlh1G67R protein to localize to meiotic chromosomes. These studies demonstrate that the Mlh1G67R mutation differentially affects the biological functions associated with Mlh1 with distinct phenotypic effects.

Results

Generation and Cancer Susceptibility Phenotype of Mlh1G67R Mutant Mice.

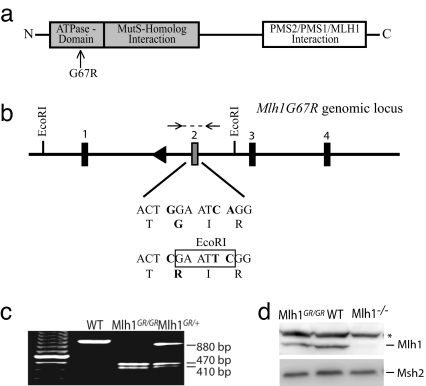

The Mlh1G67R mouse line was created by a knockin gene-targeting strategy [Fig. 1a–c and supporting information (SI) Fig. 8 in SI Appendix]. Western blot analysis revealed slightly reduced levels of cellular Mlh1G67R protein, indicating that the mutation affected protein stability (Fig. 1d). However, similar to WT Mlh1, the mutant Mlh1G67R protein was still capable of interacting with Pms2 as assessed by coimmunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged Mlh1G67R and HA-tagged Pms2 protein expressed in 293T cells (SI Fig. 9 in SI Appendix). Analysis of heterozygous or homozygous F2 animals revealed no developmental abnormalities.

Fig. 1.

The generation of Mlh1G67R mutant mice. (a) Domain structure of Mlh1. The location of the G67R mutation is indicated. (b) Schematic representation of the modified Mlh1G67R genomic locus and sequence characteristics of the G67R mutation. (c) PCR genotyping of tail DNA from Mlh1G67R mutant mice. Mlh1G67R/+, heterozygous mice; Mlh1G67R/G67R, homozygous mutant mice. After EcoRI restriction digestion of the PCR product, the WT allele is indicated by an 880-bp fragment and the Mlh1G67R mutant allele by 470- and 410-bp restriction fragments. (d) Western blot analyses of thymocyte cell extracts using anti-Mlh1 and anti-Msh2 antibodies.*, Unspecific protein recognized by the Mlh1 antisera.

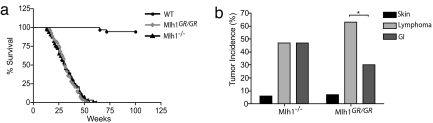

Cohorts of Mlh1G67R/G67R, Mlh1G67R/+, Mlh1+/+, and Mlh1−/− mice were monitored for survival and cancer susceptibility. Both Mlh1G67R/G67R and Mlh1−/− mice showed severely reduced survival, with only 50% of animals surviving 30 weeks of age, and all animals had died by 64 weeks of age. In contrast, 100% of Mlh1+/+ and 96% of Mlh1G67R/+ mice survived this period (Fig. 2a and data not shown). There was no difference in survival between Mlh1G67R/G67R and Mlh1−/− mice. The reduced survival in the Mlh1G67R/G67R and Mlh1−/− mutant mice was caused by an increase in cancer predisposition. The histopathological analysis of moribund mice revealed that among 66 Mlh1−/− mice, 35 had developed T and B cell lymphoma, 35 had developed small intestinal tumors (among these, 8 mice developed both lymphoma and intestinal tumors), and 4 mice developed squamous basal cell carcinoma of the skin. The analysis of 49 Mlh1G67R/G67R mice revealed a similar tumor spectrum; however, we found a significant reduction in the number of mice with intestinal tumors (Fig. 2b). Although 34 mice had developed T and B cell lymphoma, only 16 mice developed small intestinal tumors (among these, 5 mice developed both types of tumors). Histopathological analysis revealed that, of 31 intestinal tumors in Mlh1−/− mice, 19 were adenocarcinoma, and 12 were adenoma, whereas, of 18 intestinal tumors in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice, 11 were adenocarcinomas, and 7 were adenomas. In addition, four Mlh1G67R/G67R mice had also developed squamous basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Six Mlh1G67R/G67R mice died prematurely, but their tumors were not available for analysis.

Fig. 2.

Survival and tumor incidence in Mlh1 mutant mice. (a) Survival of Mlh1 mutant mice. Significantly reduced survival of Mlh1−/− and Mlh1G67R/G76R mice compared with WT mice (P < 0.0001; log-rank test) is shown. There was no difference in survival between Mlh1−/− and Mlh1G67R/G76R mice (P = 0.915; log-rank test). (b) Tumor incidence in Mlh1−/− and Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant mice. Reduced gastrointestinal (GI) tumor incidence in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice (P < 0.0296) is shown.

MSI in Mlh1G67R/G67R Mice.

To determine the MMR defect caused by the Mlh1G67R mutation, we assessed the in vivo mutator phenotype in Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant mice by analyzing MSI in tail genomic DNA (SI Fig. 10a in SI Appendix). At the dinucleotide marker D17Mit123, 25.4% of alleles tested were unstable in Mlh1−/− mice, and 21.9% of alleles were unstable in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice. In contrast, only 6.6% of alleles in Mlh1+/+ genomes were unstable, indicating highly significant increases in mutation frequency in the genomes of Mlh1−/− and Mlh1G67R/G67R mice at this marker (P < 0.0001 compared with Mlh1+/+) (SI Fig. 10b in SI Appendix). Similarly, the same marker showed significantly increased instability in intestinal epithelial cells of Mlh1−/− and Mlh1G67R/G67R mice (24.0% and 23.4%, respectively) compared with WT mice (4.2%) (P < 0.0001) (SI Fig. 10c in SI Appendix). The analysis of five different microsatellite markers in the genomes of intestinal and lymphatic tumors showed that 80% of Mlh1G67R/G67R tumors displayed a high MSI phenotype (22 of 28), with three or more microsatellites being unstable (data not shown). As expected from previous studies, the majority (79%, 25 of 32) of Mlh1−/− tumors displayed an MSI high phenotype (24, 25).

In Vitro DNA Damage Response in Mlh1 Mutant Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast (MEF) Cells.

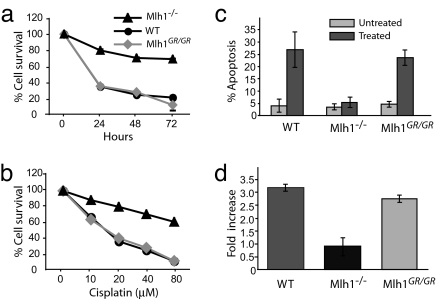

To study the impact of the Mlh1G67R mutation on the DNA damage response, we exposed Mlh1+/+, Mlh1−/−, and Mlh1G67R/G67R primary MEF strains to cisplatin. Consistent with previous results, Mlh1−/− MEFs showed increased resistance to treatment with cisplatin (Fig. 3 a and b) (26). In contrast, both Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R MEF cells displayed similar sensitivity to cisplatin exposure. The differences in sensitivity between the Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R cells and Mlh1−/− cells were highly significant (P ≤ 0.0001). The cisplatin sensitivity in Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R cells was associated with a significant increase in apoptosis (Fig. 3c) (P < 0.0001 for both Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R compared with untreated cells). In contrast, no significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells was seen in Mlh1−/− cells compared with untreated cells. In addition, consistent with previous reports (26), Mlh1−/− cells showed a defective cell cycle arrest after cisplatin treatment as shown by the reduced proportion of G2/M cells after damage-induced cell stress, whereas both Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R cells displayed normal G2/M arrest (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, in vitro-activated primary T cells of Mlh1−/− mice displayed increased resistance against cisplatin, as shown by increased survival and reduced apoptosis, whereas T cell blasts of both Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R mice were sensitive to cisplatin-induced cell death (SI Fig. 11 in SI Appendix).

Fig. 3.

Cisplatin sensitivity and apoptosis in Mlh1G67R/G67R MEF cells. MEF strains of the various Mlh1 genotypes were exposed to cisplatin for different time periods or at varying concentrations. (a) Survival of cells after exposure with 40 μM cisplatin at different time intervals. (b) Survival of cells after 48-h exposure at different cisplatin concentrations. (c) Apoptotic response to cisplatin treatment (20 μM cisplatin for 24 h) measured by TUNEL. (d) G2/M cell-cycle arrest in Mlh1G67R/G67R MEF cells. The percentage of cells in G0/G1 and G2/M were calculated for three different MEF strains for indicated genotypes. The results are shown as the fold increase of G2/M cells in treated over untreated MEFs for each genotype.

In Vivo DNA Damage Response in Intestinal Epithelia of Mlh1 Mutant Mice.

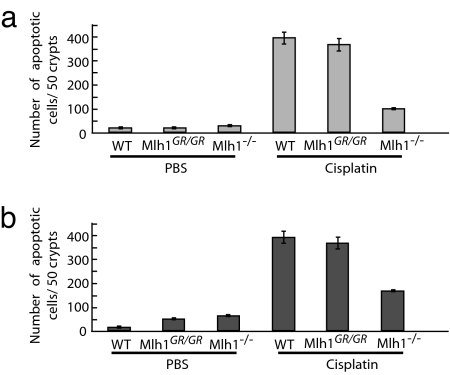

We next analyzed the in vivo response to cisplatin in the intestinal epithelium of Mlh1 mutant mice. Mlh1−/−, Mlh1+/+, and Mlh1G67R/G67R mice were injected with cisplatin or PBS, and the apoptotic response of intestinal epithelial cells was measured by TUNEL. Consistent with the results in MEF cells, Mlh1+/+ and Mlh1G67R/G67R epithelial cells in the small and large intestines of cisplatin-treated mice displayed a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells compared with the intestines of PBS-treated mice (Fig. 4 a and b). In contrast, cisplatin treatment of Mlh1−/− mice resulted in only a moderate increase in the number of apoptotic cells.

Fig. 4.

Cisplatin-induced apoptotic response of epithelial cells in the intestinal mucosa in Mlh1 mutant mice. TUNEL-positive cells 24 h after cisplatin exposure (10 mg/kg of body weight). (a) Small intestine. (b) Large intestine.

Meiotic Defects in Mutant Mlh1G67R/G67R Males.

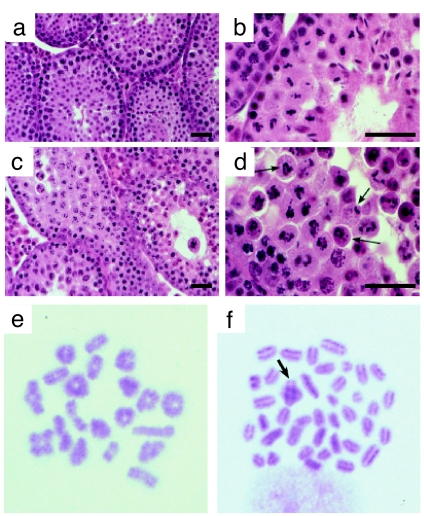

Mlh1G67R/G67R male and female mice were infertile. The seminiferous tubules in testes from Mlh1G67R/G67R males were severely depleted in spermatogenic cells compared with their WT littermates (Fig. 5a–d). Spermatogonia and early spermatocytes were visible proximal to the basement membrane within the tubules of Mlh1G67R/G67R testes and progressed through pachynema in a normal fashion. By metaphase, however, spermatocytes from Mlh1G67R/G67R males displayed abnormal spindle structures with chromosomes misaligned across the spindles (Fig. 5d, arrows). Further analysis of metaphase chromosomes in Mlh1G67R/G67R animals revealed mainly univalent chromosomes with only a few bivalents (Fig. 5f, arrow), indicating that the chromosomes undergo premature separation before aligning at the metaphase plate. These results suggest that the Mlh1G67R mutation causes the loss of chiasmata at or before metaphase I, and, as a result, most of the Mlh1G67R/G67R spermatocytes failed to progress beyond metaphase and became apoptotic. In contrast, in Mlh1+/+ males the seminiferous epithelium displayed a normal range of spermatogenic cells and contained mature spermatozoa within their lumen, indicating normal progression through metaphase and full completion of spermatogenesis (Fig. 5 a, b, and e).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant testes reveals spermatogenic failure at or before metaphase of the first meiotic division. (a–d) H&E staining of testis sections from WT (a and b) and Mlh1G67R/G67R (c and d) males, showing normal progression of spermatogenesis in WT and failure to progress beyond metaphase I in mutant adult testes. Aberrant spindle configurations are observed in testis sections from males (arrows). (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (e and f) Metaphase spreads from WT (e) and Mlh1G67R/G67R (f) spermatocytes show abnormal metaphase configurations in the mutant mice. Almost all chromosomes are univalent, with only very few crossovers remaining (arrow) in Mlh1G67R/G67R spermatocytes.

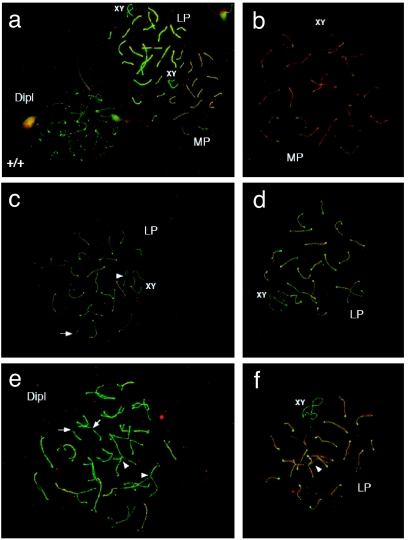

We monitored meiotic progression in adult WT and Mlh1G67R/G67R males by analyzing the assembly of synaptonemal complex proteins, Sycp1 and Sycp3, during prophase I. Although the meiotic chromosomes in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice display the typical pachytene-to-diplotene configurations similar to WT (Fig. 6 a and b), some spermatocytes from these mutant animals display premature separation of some of the chromosomes (Fig. 6 c and d) as well as abnormal intrahomolog associations at late pachytene and diplotene (Fig. 6 e and f).

Fig. 6.

Premature chromosome desynapsis in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice. Sycp1 (red) and Sycp3 (green) staining shows pachytene to diplotene chromosome configurations in WT (a) and Mlh1G67R/G67R (b–f) mouse spermatocytes. Mutant animals show premature separation of some chromosomes, particularly the XY in midpachynema (MP) and longer chromosomes in late pachynema (LP) to early diplonema (arrowheads in c) with abnormal intrahomolog associations being evident at late pachynema and diplonema (Dipl) (arrowheads in e and f). Broken synaptonemal complexes are also common (arrows in c and e). (See also larger images in SI Fig. 12 in SI Appendix).

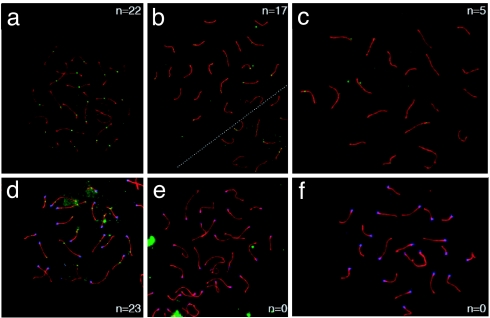

We also examined the localization of Mlh1 to meiotic foci in WT and mutant animals. Although Mlh1 containing foci, which represent sites of crossing-over, were found at the predicted frequency and localization in WT mice (Fig. 7a), the analysis of Mlh1G67R/G76R males revealed either the complete loss or a decrease in the frequency and intensity of Mlh1G67R staining (Fig. 7 b and c). The frequency of Mlh1 foci in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice ranged from 20% to 77% of that observed in WT mice (data not shown). This analysis also showed a complete absence of Mlh3 staining in pachytene spreads of Mlh1G67R/G67R animals, whereas WT animals displayed normal staining (Fig. 7 d–f).

Fig. 7.

Localization of Mlh1 (a–c) and Mlh3 (d–f) on meiotic chromosomes. (a–c) Localization of Mlh1 (green foci) on pachytene chromosome spreads from WT (a) and Mlh1G67R/G67R (b and c) males reveals a dramatic decrease in frequency and intensity of Mlh1 staining in the Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant animals. Many cells show a complete absence of Mlh1G67R staining (data not shown), but others show distinct Mlh1G67R reduction as exemplified in b and c. (d–f) Mlh3 staining (green foci) of WT (d) and Mlh1G67R/G67R (e and f) males reveals a complete absence of Mlh3 staining in pachytene spreads from Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant animals. (See also larger images in SI Fig. 13 in SI Appendix). Synaptonemal complexes are stained with anti Sycp3 antiserum (red), and centromeres are detected by CREST autoimmune serum (blue).

Discussion

We generated a mouse line carrying the MLH1G67R missense mutation that corresponds to a recurrent mutation in Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) patients and studied the consequences on individual MMR functions, cancer susceptibility, and fertility. The Mlh1G67R mutation had distinct effects on the DNA repair and damage-response functions of Mlh1. Similar to the Msh2G674A and Msh6T1217D missense mutations that we previously analyzed in mice, these functions are clearly distinguishable by the Mlh1G67R mutation. In homozygous mutant Msh2G674A and Msh6T1217D animals, the tumor onset was delayed compared with Msh2−/− and Msh6−/− mice (18, 19), consistent with the idea that the MMR-dependent DNA damage-induced apoptotic response could play an important tumor-suppressing role in the initial stages of tumorigenesis (13). Similar to Mlh1−/− mice, Mlh1G67R/G67R mice were characterized by a strong cancer predisposition phenotype. However, the number of intestinal tumors in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice was significantly reduced compared with Mlh1−/− mice. We observed the retention of a robust apoptotic response to cisplatin exposure in the epithelial mucosa of Mlh1G67R/G67R animals similar to WT mice, whereas this response was severely affected in Mlh1−/− animals. Similarly, WT and Mlh1G67R/G67R T lymphocytes displayed a robust cisplatin response, whereas T lymphocytes in Mlh1−/− mice showed increased resistance to cisplatin (Fig. 3 and SI Fig. 10 in SI Appendix). However, in contrast to intestinal epithelial cells, in T lymphocytes, the difference in the DNA damage response was not associated with a reduction in the incidence of lymphomas, although the time of death due to lymphoma was slightly delayed in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the effect of missense mutations on MMR functions can affect cancer susceptibility in a tissue-specific manner in mice. They also suggest that the MMR-dependent DNA damage response in patients carrying the MLH1G67R might differ compared with patients carrying complete MLH1 loss-of-function mutations, and it is possible that some Lynch syndrome (HNPCC)-associated cancers with missense mutations respond more favorably to chemotherapeutic treatment.

The G67R mutation affected the stability of the mutant protein and led to slightly reduced cellular levels of Mlh1G67R protein. This finding is consistent with the observation that ectopic expression of human MLH1G67R in N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU)-resistant A2780MNU ovarian carcinoma cells did only yield reduced levels of protein compared with WT MLH1. In addition, ectopic expression of MLH1G67R in A2780MNU cells did not restore sensitivity to MNU (27). We found that the cells from different tissues in Mlh1G67R/G67R mutant mice remained sensitive to cisplatin exposure. It is possible that primary cells and transformed cancer cells derived from different tissue behave differently in the MMR-dependent DNA damage response.

The Mlh1G67R mutation caused a strong DNA repair defect as indicated by the high MSI in the tissues and tumors of Mlh1G67R/G67R mice, which is consistent with studies in bacteria, yeast, and human cells and further demonstrates that normal ATPase activity is essential for the activation of the repair processes that facilitate the removal of mismatched bases (9, 11, 28–32). However, because the MLH1G67R mutation did not significantly affect the MMR-dependent cytotoxic response, normal Mlh1-mediated ATP processing is apparently not essential for the DNA damage-signaling function of Mlh1 in mammalian tissues. Different models have been proposed to explain the role of MMR proteins in DNA damage response: The futile cycle model proposes that MMR engages in futile repair cycles after treatment with alkylating agents that ultimately lead to the formation of double-strand breaks that signal cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis (33). A second model suggests that MMR proteins function as damage sensors and directly link cell cycle and apoptotic mediators to the site of DNA damage (13, 34, 35). The molecular analysis of the MLH1G67R mouse line showed that the MLH1G67R mutation resulted in reduced levels of Mlh1G67R protein but had no effect on the stability of other proteins such as Pms2 and p73 (data not shown) with which it interacts during MMR and apoptosis signaling (36, 37). The presence of Mlh1G67R protein that has lost its ability to mediate excision repair but is still capable of DNA damage signaling is consistent with the idea that the MutSα and MutLα complexes can act as molecular scaffolds to recruit downstream effectors to sites of DNA damage. In this model, MutSα and MutLα bind to either mismatched or damaged bases. Depending on the DNA ligand, the MutSα and MutLα complexes then recruit either DNA repair factors to mediate either excision repair or downstream effectors such as ATR (ataxia-, telangiectasia-, and Rad3-related) and ATRIP (ATR-interacting protein) or p73 to mediate cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis (37, 38). This scenario would also predict that, although the Mlh1G67R mutation prevents MutLα from functional interaction with downstream repair factors to initiate mismatch excision similar to other previously reported ATPase mutations in Mlh1 or Pms2 (9, 11), it should still allow the interaction of MutLα with ATM/ATRIP, p73, or other factors to signal cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Recently it was discovered that MutLα contains a latent endonuclease activity that depends on the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif in Pms2 (39, 40), and it was shown that this activity is important in the cellular response to 6-thioguanine exposure (41). It has also been reported that mutations in the ATPase centers of both MLH1 and PMS2 impair MutLα endonuclease activity (39). Our results suggest that either the Mlh1G67R mutation does not completely impair the ATPase activity of MutLα or the endonuclease activity may not be required for the cisplatin response. These predictions can be tested in future studies.

In mice, Mlh1 also has distinct functions in meiotic recombination, mismatch repair, and, possibly, DNA damage response. The MLH1G67R mutation caused a strong meiotic defect that resulted in male and female sterility. The histopathological analysis of meiotic progression in Mlh1G67R/G67R male mice revealed that, similar to Mlh1−/− mice, spermatogenesis proceeded normally through pachynema but failed to progress through metaphase I (42, 43). Consistent with this observation, cytogenetic analysis of prophase I chromosomes in Mlh1G67R/G67R males showed normal synapsis and typical pachytene and diplotene configurations of the chromosomes, however, a significant number of nuclei also showed premature desynapsis of chromosomes. In addition, metaphase chromosomes also showed premature separation of chromosomes, suggesting that the Mlh1G67R protein interfered with meiotic recombination. Consistent with this idea, mutations affecting the ATPase domain of yeast MLH1 resulted in reduced meiotic crossing-over (44). Localization studies showed that this meiotic defect in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice was caused by the inability of the mutant protein to efficiently localize to meiotic chromosomes. Therefore, at the cytogenetic level the Mlh1G67R mutation resulted in an “Mlh1 knockout” phenotype. Interestingly, the meiotic defect is different in Mlh1−/− mice, in that Mlh3 localization to chromosomes is absent in Mlh1G67R/G67R mice, whereas Mlh3 localization occurs in Mlh1−/− mice (45). Mlh1 and Mlh3 are known to form a heterodimeric complex (termed MutLγ) (5) whose function is essential for meiotic progression, and our studies demonstrate that the Mlh1G67R mutation interferes with the function of this complex and its chromosomal localization. It is possible that the mutant Mlh1G67R also interferes with MutLγ function in heterozygous mice, and it will be interesting to evaluate the possibility of more subtle meiotic defects in heterozygous animals, which may provide a model for human aneuploidy.

Materials and Methods

PCR Genotyping of Mlh1G67R Mutant Mice.

Genomic tail DNA was PCR amplified by using forward primer 5′-TGC-TGA-AAG GAC-TGC-CCT AC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCC-CTC-CTG-AAT-GAC-CAA-TA-3′, and the 880-bp PCR was subsequently digested with EcoRI.

Western Blot Analysis.

Thymocyte cell extracts (50 μg of protein) were separated on two 10% SDS/PAGE gels. Protein was transferred onto Protran membranes, and the membranes were incubated either with rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against Mlh1 (AB 9144; Abcam) or Msh2 (PharMingen).

Histopathological Analysis of Tumors.

Gastrointestinal tumors were dissected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and processed for paraffin embedding and H&E staining. Lymphomas were analyzed for surface markers by three-color flow cytometry.

MSI Analysis.

Genomic DNA from tail and intestinal mucosa was analyzed at dinucleotide markers D17Mit123 and D7Mit91 as described (22). For tumor tissue, three mononucleotide markers (U12235, Aa006036, and L24372) and two dinucleotide markers (D7Mit91 and D17Mit123) were analyzed. PCR was performed by using Cy5-end-labeled primers (30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min). PCR products were separated on denaturing acrylamide gels and autoradiographed.

Cytotoxicity Assays.

MEFs were exposed to cisplatin and MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assays were performed according to standard procedures. MEFs were seeded at 2 × 104 cells per well in a 24-well plate. The cells were exposed to various concentrations of cisplatin and analyzed after 24, 48, and 72 h of treatment. The percentage of cell survival was calculated as (treated cells per untreated cells × 100). The apoptotic response to drug exposure was measured by TUNEL (Promega). The experiments were performed for three different MEF strains for each Mlh1 genotype and repeated at least three times for each strain.

In Vivo DNA Damage Response.

Three animals of each Mlh1+/+, Mlh1−/−, and Mlh1G67R/G67R genotype were injected intraperitoneally with cisplatin (10 mg/kg of body weight) or saline solution. All animals were killed 24 h after injection, and their intestines were fixed in 10% formamide. Paraffin-embedded histological sections from small and large intestines were stained with TUNEL (Promega). The number of TUNEL-positive cells per 50 crypts in the small and large intestines were counted, and the means of three mice in each group were calculated.

Cell Cycle Analysis.

MEF cells (1.0 × 106) were either treated with 40 μM cisplatin for 36 h or left untreated. The cells were subsequently fixed in 70% ethanol, stained with propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Analysis of Meiotic Prophase I.

The testes from male mice were fixed in Bouin's or 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Chromosome spreads were prepared as described (23) and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence using antibodies against synaptonemal complex proteins (Sycp1 and Sycp3), MutL homologs (Mlh1 and Mlh3), and centromers (CREST). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to Cy3, Cy5, or fluoroscein (Jackson Immunochemicals). Images were visualized with the aid of a Zeiss Axioimager Z1 equipped with a cooled CCD Axiocam MRM camera, and processed by using Axiovision 4.0 software (Zeiss).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Martina Doehler for excellent technical support. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA76329, CA102705, and CA93484 (to W.E.), CA84301 (to W.E. and R.K.), and HD41012 (to P.E.C.) and Center Grant CA13330 (to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and an Irma T. Hirschl Career Scientist Award (to W.E.). B.K., A.R., and C.R. were supported by Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft graduate college 639 grants.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0800276105/DC1.

References

- 1.Peltomaki P, Vasen HF. Mutations predisposing to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: Database and results of a collaborative study. The International Collaborative Group on Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1146–1158. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan H, et al. Conversion of diploidy to haploidy. Nature. 2000;403:723–724. doi: 10.1038/35001659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA mismatch repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schofield MJ, Hsieh P. DNA mismatch repair: Molecular mechanisms and biological function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:579–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolas NK, Cohen PE. Novel and diverse functions of the DNA mismatch repair family in mammalian meiosis and recombination. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;107:216–231. doi: 10.1159/000080600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buermeyer AB, Deschênes SM, Baker SM, Liskay RM. Mammalian mismatch repair. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:533–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolodner RD, Marsischky GT. Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raschle M, Dufner P, Marra G, Jiricny J. Mutations within the hMLH1 and hPMS2 subunits of the human MutLalpha mismatch repair factor affect its ATPase activity, but not its ability to interact with hMutSalpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21810–21820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall MC, Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA. Differential ATP binding and intrinsic ATP hydrolysis by amino-terminal domains of the yeast Mlh1 and Pms1 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3673–3679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomer G, Buermeyer AB, Nguyen MM, Liskay RM. Contribution of human mlh1 and pms2 ATPase activities to DNA mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21801–21809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stojic L, et al. Mismatch repair-dependent G2 checkpoint induced by low doses of SN1 type methylating agents requires the ATR kinase. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1331–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.294404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fishel R. The selection for mismatch repair defects in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: revising the mutator hypothesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7369–7374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loeb LA. A mutator phenotype in cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3230–3239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomlinson I, Bodmer W. Selection, the mutation rate and cancer: Ensuring that the tail does not wag the dog. Nat Med. 1999;5:11–12. doi: 10.1038/4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin DP, et al. An Msh2 point mutation uncouples DNA mismatch repair and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:517–522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang G, et al. Dominant effects of an Msh6 missense mutation on DNA repair and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Chapelle A. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:769–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alazzouzi H, et al. Low levels of microsatellite instability characterize MLH1 and MSH2 HNPCC carriers before tumor diagnosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:235–239. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei K, et al. Inactivation of Exonuclease 1 in mice results in DNA mismatch repair defects, increased cancer susceptibility, and male and female sterility. Genes Dev. 2003;17:603–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolas NK, et al. Localization of MMR proteins on meiotic chromosomes in mice indicates distinct functions during prophase I. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:447–458. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prolla TA, et al. Tumour susceptibility and spontaneous mutation in mice deficient in Mlh1, Pms1 and Pms2 DNA mismatch repair. Nat Genet. 1998;18:276–279. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edelmann W, et al. Tumorigenesis in Mlh1 and Mlh1/Apc1638N mutant mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1301–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong JG, et al. The tyrosine kinase c-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature. 1999;399:806–809. doi: 10.1038/21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blasi MF, et al. A human cell-based assay to evaluate the effects of alterations in the MLH1 mismatch repair gene. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9036–9044. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo E, Suzuki H, Horii A, Fukushige S. A yeast two-hybrid assay provides a simple way to evaluate the vast majority of hMLH1 germ-line mutations. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3302–3308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellison AR, Lofing J, Bitter GA. Human MutL homolog (MLH1) function in DNA mismatch repair: A prospective screen for missense mutations in the ATPase domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5321–5338. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Junop MS, Yang W, Funchain P, Clendenin W, Miller JH. In vitro and in vivo studies of MutS, MutL and MutH mutants: Correlation of mismatch repair and DNA recombination. DNA Repair. 2003;2:387–405. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prolla TA, Pang Q, Alani E, Kolodner RD, Liskay RM. MLH1, PMS1, and MSH2 interactions during the initiation of DNA mismatch repair in yeast. Science. 1994;265:1091–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.8066446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raevaara TE, et al. Functional significance and clinical phenotype of nontruncating mismatch repair variants of MLH1. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:537–549. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karran P, Bignami M. DNA damage tolerance, mismatch repair and genome instability. BioEssays. 1994;16:833–839. doi: 10.1002/bies.950161110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li GM. The role of mismatch repair in DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Oncol Res. 1999;11:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kat A, et al. An alkylation-tolerant, mutator human cell line is deficient in strand-specific mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6424–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buermeyer AB, Wilson-Van Patten C, Baker SM, Liskay RM. The human MLH1 cDNA complements DNA mismatch repair defects in Mlh1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1999;59:538–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimodaira H, Yoshioka-Yamashita A, Kolodner RD, Wang JY. Interaction of mismatch repair protein PMS2 and the p53-related transcription factor p73 in apoptosis response to cisplatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2420–2425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438031100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshioka K, Yoshioka Y, Hsieh P. ATR kinase activation mediated by MutSalpha and MutLalpha in response to cytotoxic O6-methylguanine adducts. Mol Cell. 2006;22:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell. 2006;126:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadyrov FA, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLa is a mismatch repair endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37181–37190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erdeniz N, Nguyen M, Deschenes SM, Liskay RM. Mutations affecting a putative MutLalpha endonuclease motif impact multiple mismatch repair functions. DNA Repair. 2007;6:1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edelmann W, et al. Meiotic pachytene arrest in MLH1-deficient mice. Cell. 1996;85:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker SM, et al. Involvement of mouse Mlh1 in DNA mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over. Nat Genet. 1996;13:336–342. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffmann ER, Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA, Borts RH. MLH1 mutations differentially affect meiotic functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2003;163:515–526. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipkin SM. Meiotic arrest and aneuploidy in MLH3-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2002;31:385–390. doi: 10.1038/ng931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.