Abstract

Cholera, an infectious disease with global impact, is caused by pathogenic strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. High-throughput functional proteomics technologies now offer the opportunity to investigate all aspects of the proteome, which has led to an increased demand for comprehensive protein expression clone resources. Genome-scale reagents for cholera would encourage comprehensive analyses of immune responses and systems-wide functional studies that could lead to improved vaccine and therapeutic strategies. Here, we report the production of the FLEXGene clone set for V. cholerae O1 biovar eltor str. N16961: a complete-genome collection of ORF clones. This collection includes 3,761 sequence-verified clones from 3,887 targeted ORFs (97%). The ORFs were captured in a recombinational cloning vector to facilitate high-throughput transfer of ORF inserts into suitable expression vectors. To demonstrate its application, ≈15% of the collection was transferred into the relevant expression vector and used to produce a protein microarray by transcribing, translating, and capturing the proteins in situ on the array surface with 92% success. In a second application, a method to screen for protein triggers of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) was developed. We tested in vitro-synthesized proteins for their ability to stimulate TLR5 in A549 cells. This approach appropriately identified FlaC, and previously uncharacterized TLR5 agonist activities. These data suggest that the genome-scale, fully sequenced ORF collection reported here will be useful for high-throughput functional proteomic assays, immune response studies, structure biology, and other applications.

Keywords: cholera, functional proteomics, immunity, ORF clones, protein microarray

The bacterium Vibrio cholerae causes infectious epidemics of watery diarrhea that can lead to severe dehydration and death within a period of hours or days (1–4). Of >200 V. cholerae serotypes identified thus far, only serogroups 01 and 0139 are associated with infectious human pandemics. These are endemic to regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where they continue to pose a threat to human health (3). Seven pandemics of cholera have been registered during the past two centuries in endemic areas (5, 6). Epidemic cholera generally has a higher fatality rate, in part because of the lack of organized response structures. In 1994, an estimated 12,000 people died in eastern Zaire in <3 weeks. The case-fatality rate in a single day reached 48% (7) until it was reduced to <1% by the action of Bangladesh specialists (8).

In addition to its impact on world health, factors including the high case-mortality rate in epidemics, the ease of spread through contaminated food and water supplies, the rapid progress of the disease, the production of a toxin, and the absence of an effective vaccine have led the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to classify V. cholerae as a category B pathogen, which has placed it on the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases priority list for potential bioterrorism agents (9).

Considerable effort has been devoted to finding an effective vaccine. Because of the oral–fecal transmission route, recent vaccines have been oral, based on inactivated bacteria or live attenuated strains (10, 11). Despite inducing seroconversion, the low level of protection could not justify their use (12, 13). Nevertheless, some live attenuated strain vaccines, such as Peru-15, are still being developed and tested (14).

Infection in endemic areas or in research volunteers confers protection from reinfection for several years, encouraging the notion that a vaccine can be found. Protection correlates with a vibriocidal activity in serum, revealing the importance of the humoral response to the immunity (15, 16). Although anti-LPS activity is a component (17), anti-LPS titers alone did not correlate with protection when familiar contacts with cholera patients were screened in rural Bangladesh, suggesting the presence of other protective antibodies in serum (18). The ability to screen all proteins in the proteome would allow the identification of proteins that participate in this immune response and ultimately lead to vaccination or pharmaceutical treatments.

Recent years have seen the accelerated development of technologies that study proteins in high throughput. Referred to as functional proteomics, these methods support the global study of protein interactions, enzymatic activities, and immune responses. These applications all rely on the availability of cloned copies of the protein coding sequences to produce proteins in vivo or in vitro for these assays. These protein-coding clones must be clonally isolated and fully sequence-verified to ensure accurate interpretation of the experiments results. Assembling such clones requires automated and highly quality-controlled processes, followed by careful sequence analysis and evaluation to eliminate any inappropriate clones (e.g., truncation mutations). We and others have developed robust pipelines for the production of fully sequence-verified, genome-scale plasmid collections of protein coding sequences for a variety of organisms (19–27). In this context, we have initiated the full length expression-ready gene collection (FLEXGene), which comprises plasmid clones bearing complete ORFs situated in recombinational cloning vectors. These vectors enable the rapid and efficient in-frame transfer of coding sequences from master vectors to virtually any protein expression vector in a single conservative biochemical step, allowing the transfer of entire libraries of genes and enabling the broadest possible range of experimentation (19). The FLEXGene effort has included large collections of human kinases and breast cancer-related genes (26, 28), complete genome collections for Saccharomyces cerevisiae (22), Yersinia pestis, and Francisella tularensis (29), as well as a collection for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (30), which are available at http://plasmid.hms.harvard.edu, as will be this collection.

The complete genome sequence of V. cholerae O1 biovar eltor str. N16961 was reported in 2000 (31) with a total of 3,885 predicted ORFs. Unlike most bacteria, V. cholerae has two chromosomes: chromosome 1 (≈2.9 Mb) and chromosome 2 (≈1.1 Mb) (31), and chromosomes 1 and 2 contain 2,770 and 1,115 ORFs, respectively. Approximately 54% of the ORFs are similar to proteins of known function [58% and 42% for chromosomes 1 and 2, respectively (31)].

Here, we report the assembly of a complete FLEXGene ORF collection for V. cholerae [supporting information (SI) Table 4] using a highly automated, quality-controlled clone production pipeline that includes full sequence verification and analysis of each clone in the collection. This resource enables a wide variety of genetic and system-wide assays. Coupled with new technologies such as protein microarrays, it might allow the documentation of the immune responses to, and functional characterization of, each protein of this pathogen. These results in turn may lead to new vaccine and therapeutic strategies, and better understanding of the pathogen biology.

Results

Importing Annotated Sequence Information for a Genome-Scale Set of 3,887 V. cholerae Protein Coding Sequences.

We populated a local database with the start and stop position, as well as the full sequence, of each coding region from the genome annotations available for V. cholerae O1 biovar eltor str. N16961 (from here on referred to as V. cholerae) from both the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and The Institute for Genome Research (TIGR) (31). Although the annotated sequence information at TIGR and NCBI was identical for 3,819 predicted V. cholerae ORFs, some differences were noted (Table 1). We imported the most inclusive set (i.e., the union of the two annotations; 3,887 ORF sequences) into our clone production database, FLEXGene (19, 22).

Table 1.

Source of protein annotation in genome

| Source | NCBI | TIGR | Project target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total ORF count | 3835 | 3885 | 3887 |

| Identical ORFs | 3819 | 3819 | 3819 |

| Same ORF, different annotation | 13 | 13 | 13 (TIGR version) |

| ORFs missing from other source | 3 | 53 | 55* |

*VC1131 was not attempted because of size (45 bp).

This set includes a small number of ORFs annotated as having one or more “authentic frameshifts” that predict truncated polypeptides for V. cholerae compared with corresponding ORFs in other bacteria (Table 2). For each of the 3,887 ORFs represented in FLEXGene, the following values were included: a unique FLEXGene sequence identifier; GenBank accession/GI number for genomic and protein sequence; protein gene symbol and product name; genome location and coding strand information; locus tag, which is the systematic gene identifier (i.e., the “VC” number); numerical value for CDS length; percentage GC content; and nucleotide sequence of the ORF.

Table 2.

Description of ORFs with reference CDS issues

| Reference annotation | ORFs count | Clone matching to ref. | Clone not matching to ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic frame shift | 41 | 15 | 26 |

| Authentic point mutation | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Reference CDS not multiple of 3, frame shift not annotated | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Reference CDS with in-frame stop, not annotated | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ambiguous base in genome sequence | 16 | 2* | 14 |

*Clones not finalized in sequencing.

Highly Automated Amplification of the V. cholerae ORFeome.

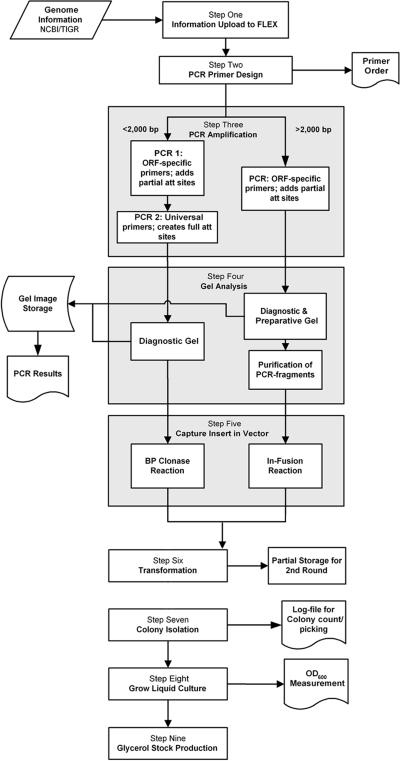

We generated ORF clones via a processing pipeline outlined in Fig. 1 that runs by robotics supported by FLEXGene. Digital images of agarose gels, robotic colony counts, and OD600 readings of liquid cultures were stored, enabling retrieval of the clone history for each clone.

Fig. 1.

Highly automated clone production pipeline. ORFs with an expected size ≤2,000 bp were treated differently at PCR, gel analysis, and capture compared with larger ORFs (Steps 3, 4, and 5). Barcode-labeled plates, blocks, and dishes were used at all stages, and appropriate results (gel images, colony counts, OD600, etc.) were stored in the FLEXGene LIMS as indicated, enabling clone history retrieval.

ORF-specific PCR primers were designed to amplify all protein coding sequences by using genomic DNA as template in one or two rounds of PCR amplification depending on ORF size (Fig. 1) (22, 25). We normalized all ORFs to start with ATG and replaced stop codons with TTG (Leu) to allow for the addition of C-terminal epitope tags.

An overall success of >99% at the PCR step was observed (3,863 of 3,887 PCRs), with an overrepresentation of clones >2,000 bp among the failures.

Automated Isolation of ORF Clones.

The PCR products were captured in the Gateway vector pDONR221, by using one of two strategies. ORFs >2,000 bp were captured by using the In-Fusion cloning protocol because it is more efficient for large clones; ORFs 2,000 bp or smaller were captured by using the standard Gateway BP capture reaction (Fig. 1) (22). All constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli and individually plated for robotic single-colony isolation. Colony counts were recorded, and one isolate per ORF was collected and used to generate glycerol stocks.

The success rate for small ORFs was 99% (3,610 of 3,638 ORFs), whereas that for large ORFs was 89% (205 of 225). In total, we successfully obtained clonal glycerol stocks for 3,815 of 3,887 ORFs, a success rate of >97% (Table 3).

Table 3.

V. cholerae clone production and sequence validation summary

| Item | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORF target | 3,887 | 783 | 3,887 |

| Avg. ORF size | 922 | 889 | 922 |

| PCR success rate, n (%) | 3,863 (99.4) | 781 (99.7) | 3,885 (99.9) |

| Capture success rate, n (%) | 3,815 (98.1) | 781 (99.7) | 3,884 (99.9) |

| Isolate picking | 1 per ORF | 2–4 per ORF | 1.5 per ORF |

| Clones for sequence validation | 3,815 | 1,957 | 5,772 |

| No. of reads | 12,823 | 5,653 | 18,476 |

| Avg. no. of reads per clone | 3.4 ± 2.6 | 2.9 ± 3.1 | 3.2 ± 2.7 |

| Mutation rate | 1 of 2,531 | 1 of 1,002 | 1 of 1,756 |

| Accepted clones, n (%) | 3,125 (81.9) | 1,202 (61.4) | 4,327 (75.0) |

| Match perfect with ref., n (%) | 2,913 (93.2) | 1,107 (92.1) | 4,020 (92.9) |

| With silent mutation(s) only, n (%) | 76 (2.4) | 14 (1.2) | 90 (2.1) |

| With 1 missense mutation, n (%) | 136 (4.4) | 81 (6.7) | 217 (5.0) |

| Rejected clones, n (%) | 690 (18.1) | 755 (38.6) | 1,445 (25.0) |

| Linker changes | 39 | 25 | 64 |

| CDS changes (ins/del/nonsense/mis) | 205 | 274 | 479 |

| Clones rejected for other reasons* | 446 | 456 | 902 |

| Clones needed to finish a gene | NA | 2.9 | 1.5 |

| Accepted ORFs, n (%) | 3,125 (80.4) | 682 (87.1) | 3,761 (96.8) |

Avg., average; ref., reference.

*Other possible reasons for clone rejection include: duplicate clones of finished gene, no insert was present, insert mismatching, multiple attempts to resolve discrepancy(ies) failed, or clone failed to grow during or after validation.

DNA Sequence Analysis Reveals High-Quality Capture.

To verify the clones, we fully sequence-verified all of the V. cholerae ORF clones using a process that was managed and analyzed by the automated clone evaluation software, ACE (32).

Acceptance into the collection required either an exact polypeptide match or no more than one amino acid substitution when full, high-quality sequence coverage was obtained. Clones with insertions, deletions, nonsense mutations (i.e., truncations), or two or more amino acid differences were rejected. In addition, clones with nucleotide changes in the att-site sequences were rejected because of their effect on the recombination reaction.

We encountered difficulty obtaining quality sequence reads from many clones <500 bp. The sequence traces had clear and interpretable signal peaks that ended abruptly and prematurely at the same position within the attL sequences, suggesting the formation of a stem loop structure between the flanking att-site sequences. Transferring the ORFs to an expression vector, pANT7-cGST, which has a much shorter attB sequence, enabled full-length sequencing of these clones.

On a single pass for the genome, we accepted clones for 81.9% of the ORFs (3,125 of 3,815 ORFs; Table 2). Of these, 93.2% (2,913 of 3,125) were identical to the reference sequence at the nucleotide level. Of the accepted but nonidentical clones, 136 had one amino acid change.

Second-Round Clone Production Leads to >97% Coverage of Predicted V. cholerae ORFs.

A second round of cloning to obtain the missed clones was approached in two steps. Initially, we replated the frozen transformation reactions that were available for 513 ORFs of the 762 missing ORFs and sequenced up to four additional isolates for each (Fig. 1). After this, a de novo cloning round for 382 ORFs was needed to obtain clones that had failed all previous steps. These included 72 ORFs that failed PCR, capture, or transformation and 290 ORFs that had failed in sequencing. New cloning primers were used with the same workflow, except that two independent clones per target were isolated instead of one, and all clones were transferred to and sequenced in the expression vector.

Sequence Analysis Summary.

In total, 5,772 clones were analyzed, leading to 4,327 acceptable clones for 3,761 genes (an average of 1.5 analyzed clones per successful ORF). Among redundant clones, the closest match to the reference sequence was included in the final collection.

Overall, 92.9% of accepted clones, covering 3,125 of 3,761 ORFs were a perfect match to the published genome sequence (Table 3). Silent mutations were detected in 2.1% (90 clones) and 5% (217 ORFs) had one amino acid change. Thus, acceptable clones were obtained for 3,761 ORFs (97%; complete listing in SI Table 4).

Potential Adjustments to the Genome Annotation.

The target sequences included 49 ORFs whose official annotated CDS lengths were not an integer multiple of three (Table 2). These included 41 genes annotated to have an “authentic frame shift”, 4 listed to have an “authentic point mutation,” and 4 with no explanation provided by either NCBI or TIGR. For 22 of the 49 ORFs, the sequence of our clone(s) confirmed the presence of a frame shift or stop codon that would lead to a “shorter” polypeptide in V. cholerae. However, for 27 of the 49 ORFs (SI Table 5), we did not find the reported frame shift in any of the isolates we sequenced, suggesting potential errors in the genome sequence and/or annotation or subtle strains differences in the genomic template we used. Multiple independent isolates confirmed the sequence, and the clones were therefore included.

In addition, 31 of the 123 ORFs that failed sequencing demonstrated multiple isolates with identical insertion/deletion discrepancies that led to rejection (SI Table 6). This finding may suggest that the genome sequence may be in error for these ORFs. These clones were not included in the final collection.

V. cholerae ORF Clone Expression in a Heterologous System and on Protein Microarrays.

As a first functional test of these clones, we transferred the inserts from ≈10% of the collection to a bacterial expression vector and expressed GST fusion proteins in E. coli and confirmed by Western blot as described (25, 33, 34). Appropriately sized fusion proteins were detected for 280 (77%) of the tested ORFs. No signal was detected for 62 ORFs, and aberrantly sized polypeptides were observed for an additional 34 ORFs (9%) (SI Fig. 4 and SI Table 7). Overall these results are well within the previously reported range for other ORF collections (25, 33).

We also tested this set of ORFs for protein expression and capture on a protein microarray method called NAPPA (nucleic acid programmable protein array), previously developed in our laboratory. Instead of the standard process of printing purified proteins onto a microarray surface, NAPPA entails printing full-length cDNAs encoding the respective proteins along with a capture antibody. At the time of assay, this “cDNA” array is converted into a protein array by transcribing and translating the proteins in situ. The nascent proteins are captured to the array surface by capture antibody directed at a glutathione-S-transferase (GST) tag added to the carboxyl end of each protein by the expression vector. This obviates some common problems of protein-spotted protein microarrays, such as the challenges inherent in purifying the proteins and the short shelf life of many purified proteins (35). The C-terminal location of the tag ensures that proteins are fully translated and can potentially be confirmed with a different anti-GST antibody. Here, we printed various concentrations of purified GST protein to allow for semiquantitative assessment of the yield of captured proteins. Protein was readily detected for 319 of the 345 clones tested (92%) (Fig. 2). For the 26 failed plasmids, 23 did not display sufficient DNA on the array surface as measured by picogreen binding, whereas 3 failed protein expression even when sufficient DNA was observed (SI Table 7). As expected, control features without DNA or purified GST protein did not show measurable reactivity.

Fig. 2.

Representative protein microarray (NAPPA) results of V. cholerae proteins. ORFs (n = 346) were transferred and arrayed as plasmid DNA onto protein microarrays, and expression on the array was tested. (A and B) The DNA-to-protein relationships. (Upper) Picogreen detection of DNA. (Lower) The corresponding GST protein. (A) Controls spotted onto the array; on the left and right are 8 features for plasmids that do not encode protein, and in the center are 12 features of purified GST protein. (B) A comparison of 32 V. cholerae ORFs; all ORFs display DNA, but variation in ORF-specific protein expression/capture. (C) Examples for the entire set of controls and ORFs tested on NAPPA; left array, DNA detection by picogreen staining; right array, protein expression/capture by anti-GST antibody.

V. cholerae Fusion Proteins Are Active in Biological Assays.

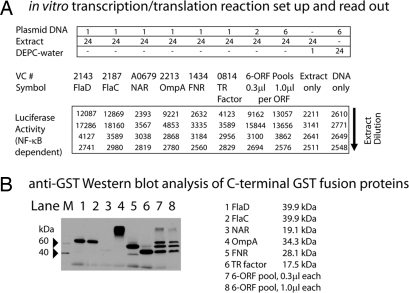

As a proof for biological activity, we tested in an assay designed to discover Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists whether in vitro-produced C-terminal GST-tagged V. cholerae proteins were biologically active. To address this question, we used A549 NF-κB reporter cells in which a luciferase gene is transcribed under the control of an NF-κB-responsive promoter. A549 cells express endogenously TLR5, and thus, show luciferase expression as response after being challenged with bacterial flagellins (36–39). As shown in Fig. 3a, high-level induction of NF-κB was detected in A549 cells exposed to in vitro transcription/translation extracts that contained plasmids coding for GST fusion proteins to the V. cholerae flagellins FlaD and FlaC (Fig. 3, columns 1 and 2) in an extract-dependent manner. In addition, NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activation was also detected in cells treated with a GST-fused outer membrane protein, OmpA (Fig. 3A, column 4). Extracts were positive when these proteins were synthesized either alone or in combination with five other V. cholerae proteins. Two control mixtures, either only extracts or only plasmid DNA, did not stimulate NF-κB activation. GST fusion protein synthesis was confirmed by Western blot analysis using an anti-GST antibody (Fig. 3B). VCA0679 (periplasmic nitrate reductase), naturally having a heme group as cofactor, was not produced (lane 3), and VC2213 (OmpA) was detected at abnormally high molecular weight (lane 4), potentially because of forming stable multimers.

Fig. 3.

V. cholerae proteins expressed in vitro are active in biological assays. (A) Six different proteins were produced alone or together as a pool. After in vitro protein production, 10 μl of each RRL mixture and its serial dilutions were added to treat A549 reporter cells for 4 h. Luciferase-based NF-κB activation was shown in the bottom. Squares shown in red indicate positive NF-κB activation. FlaD, flagellin D; FlaC, Flagellin C; NAR, nitrate reductase; OmpA, outer membrane A; FNR, anaerobic transcriptional activator; TR Fac, transcription factor. (B) Western blot analysis of in vitro-synthesized proteins.

To further confirm the feasibility to identify innate immunity candidates, we used the A549 activation screen to examine a subset of the ORFeome library consisting of 552 proteins expressed in 94 pools of five or six different ORFs each (SI Table 8). We found three pools with a positive response in this screen, with two of these pools containing plasmids that were known or predicted to be TLR5 agonists, FlaA (flagellain core protein A, VC2188), and FlaC (VC2187), respectively. However, pool G6 was entirely made up of plasmids coding for proteins previously not known to be either activators of the innate immune system or agonist of TLR5. Repeated screening confirmed that pool G6 encodes proteins that exhibit TLR5 stimulation, and further analysis of this pool to identify and characterize the relevant ORF (S.S.Y., A. Thanawastien, W.R.M., J.L., and J.M., unpublished results). In conclusion, the V. cholerae FLEXGene library can be used to efficiently discover proteins with new biological activities of interest.

Discussion

It has been almost a century since V. cholerae was identified as the causative agent of cholera, yet the disease remains a leading cause of death in tropical countries, and new endemic outbreaks continue to occur with some frequency. Prevention of cholera suffers from the lack of an effective and affordable vaccine, despite a variety of efforts to produce one from heat-treated, attenuated and nonpathogenic V. cholerae strains. To open up possible routes to vaccine and therapeutics development, we used a highly automated cloning pipeline and performed end-to-end sequencing to produce a complete clone collection that covers protein coding regions in the V. cholerae genome. Importantly, this collection will make it possible to perform a direct analysis of each individual V. cholerae protein's contribution to the immune responses in previously infected subjects.

We encountered several instructive challenges during the cloning process. We noted that the sequence analysis of short ORFs (<500 bp) is particularly problematic using a vector containing attL sequences flanking the insert. The most likely explanation for this was the nature of the attL1 and L2 sequences, which contain nearly identical extended direct repeats (90 of 94 nt) at both ends of the insert that may form heat-stabile secondary structures. Transfer of the inserts to expression vectors containing attB sequences (60 nt shorter) rectified this problem.

We also encountered several potential errors in the published genome sequence or its annotation, including: a set of genes that did not display authentic frame shifts annotated in the genome, and conversely, a small number of ORF sequences for which multiple independent isolates exhibited identical frame shift-causing truncation mutations. The sequence data reported here should help to update the genome annotation for V. cholerae.

As shown for a randomly selected set of clones, use of the clones for high-throughput protein production in E. coli resulted in a success rate well within a published range for other clone collections (25, 33, 34). Most proteins (242 ORFs) were expressed by both protein expression methods. In general, the NAPPA method was more successful, achieving a 99% success rate for features that had adequate DNA. In the future, the protein microarrays may prove useful for clinical proteomics applications such as serum screens to identify vaccine candidates, studies to identify immune biomarkers of infection, and as tools to track the success of response to vaccines.

In addition, we used this ORF collection in a biological screening approach to identify Toll-like receptor agonists. We initially tested the feasibility with known agonists of TLR5 and tested a subset of other ORFs in pools of five to six ORFs for TLR5-mediated NF-κB stimulation with a reporter gene assay. This approach was validated by confirming FlaC and FlaA activity either alone or by using this pooling strategy and further led to a promising finding of an activity in one of the pools in this screen. Although this will need further analysis, this pilot screen shows the potential of a well annotated ORF collection for a microorganism in the identification of biomedically relevant proteins heretofore not identified. In this regard, it is interesting to note that adverse symptoms experienced by human subjects ingesting two attenuated cholera vaccines were reported to be mitigated by introduction of mutations that blocked flagella expression (40). Thus, the screening of FLEX gene libraries for TLR agonists can potentially identify bacterial ligands whose deletion from live attenuated vaccines will render them safer and less prone to induction of adverse side effects. A complete screen of the entire V. cholerae proteome remains to be completed.

These preliminary results for protein expression and functional application, together with the high-quality standard applied to the collection, suggest that the plasmid clone resource created here will be useful for a wide variety of assay types and experimental approaches to the study of V. cholerae, including detailed studies of the immune responses in infected individuals and genetic screens to study the pathways of essential genes.

Information about these clones can be found at our own center, PlasmID (http://plasmid.med.harvard.edu/PLASMID/), and the Resource Center for Biodefense Proteomics Research (http://www.proteomicsresource.org/) Any or all of the clones here can be obtained from PlasmID (http://plasmid.med.harvard.edu/PLASMID/) and the Pathogen Functional Genomics Resource Center (PFGRC) (http://pfgrc.tigr.org/).

Materials and Methods

Import of Annotated Genome Information for V. cholerae.

Protein-coding regions that were annotated based on the genome sequence of V. cholerae N16961 “El tor” were downloaded from NCBI and TIGR (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=genomeprj&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=36 and http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR2/GenomePage3.spl?database=gvc). A text parser was developed in-house to extract sequences and annotation of predicted ORFs downloaded from NCBI or TIGR.

ORF-Specific Primer Design and Strategic 96-Well Plate Organization.

ORF sequences were imported into the FLEXGene LIMS (http://flex.med.harvard.edu/FLEX/), and primer sequences were designed by using a nearest-neighbor algorithm, with primers adjusted to achieve a Tm = 58°C. Moreover, start codon sequences were normalized to ATG (Met) and natural stop codons were replaced with TTG (Leu) to allow for 3′ tags. The primers also included fixed sequences that correspond to partial att sequences that flank the ORF in the resultant plasmid clones (22).

PCR amplicons of different sizes were treated differently in two groups: those >2,000 bp and those smaller. Within each group, the ORFs were arranged on 96-well production plates in a saw-tooth pattern to enable rapid visual detection of ORFs that failed to amplify or that amplified the wrong size. This also reduced cross-contamination during gel isolation. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies as 50 μM normalized solutions and diluted to 0.083 μM before use in PCRs.

PCR and Capture in the Entry Vector, pDONR221.

PCR was performed in barcode-labeled, 96-well plates and verified by images of agarose gel electrophoresis that were uploaded into FLEXGene. PCR products representing ORFs >2,000 bp were isolated from the gel and purified before capture in linearized entry vector as described (22).

PCR products representing smaller ORFs were captured by using the BP Clonase-based capture method (Invitrogen), following protocols described in ref. 25.

Clonal Isolation and Production of Glycerol Stocks.

All products were transformed into DH5α T1-resistant E. coli, plated to 48-sector LB/agar dishes. A customized Megapix robot (Genetix) was used to count colonies, capture an image, isolate the indicated number of single colonies from each sector of the agar dish, and inoculate the colony into 1 ml of growth media (LB/antibiotic). Overnight culture growth at 37°C was verified by OD600 measurement, and aliquots were stored at −80°C as 15% glycerol stocks.

Plasmid DNA Preparation, Sequencing, and Analysis.

Plasmid DNA was prepared as described (30). All DNA sequencing was performed at the Dana–Farber/Harvard Cancer Center DNA Resource Core by using standard M13 or gene-specific primers (sequences available upon request).

For analysis, sequence data and annotated ORF reference sequences were imported into the Automated Clone Evaluation (ACE) suite of software tools (32). ACE was then used to perform all DNA sequence and clone evaluation steps, including sequence quality assessment, contig assembly, identification of coverage gaps, design of oligonucleotide primers for internal sequencing, conceptual translation of experimentally determined sequence contigs, and automated acceptance and rejection of individual clone samples based on user-defined rules for minimal and maximally acceptable differences between the experimental and reference sequences at the nucleotide and amino acid levels.

Transfer of ORFs from the Entry Vector into E. coli Expression Vectors.

Transfer reactions from pDONR221 into either pANT7-cGST (35) or pDEST-GST (33) were done with LR kits from Invitrogen, following the manufacturer's instructions and as described (22, 25, 30). Transfer reactions were transformed into a T1-resistant E. coli DH5α host strain and plated onto LB-agar/ampicillin 48-well grid plates for single colony selection. Individual isolates were inoculated by using robotics as described above. Glycerol stocks were generated and stored for each isolate.

Induction of Protein Expression and GST Immunoblotting.

Glycerol stock cultures of expression clones in pDEST-GST were spotted on agar plates with appropriate antibiotic selection to generate even growth conditions, incubated at 37°C, and used to inoculate liquid cultures in 96-well plates. After growth overnight at 37°C, liquid cultures were diluted 1:500 and regrown until an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 was reached. Protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG (final concentration), and cultures were incubated for 4 h at room temperature with constant shaking. One hundred microliters of each culture was centrifuged, and cell pellets were dissolved in 20 μl of SDS/PAGE sample buffer, followed by separation on precast 10% Criterion gels (Bio-Rad). Immunoblot analysis using monoclonal anti-GST antiserum was performed as described (35).

Protein Microarray (NAPPA) Synthesis and Expression.

Expression constructs were grown in appropriate media (LB-amp) and DNA harvested and purified and modified before the array as described (35). Modified DNA together with polyclonal anti-GST antibody (Amersham) were applied to presilanized glass slides with a commercial DNA microarray robot (Genetix), followed by incubation with PicoGreen (1:600; Molecular Probes) to confirm the presence of DNA at each feature or with the TNT system (T7; Promega) for in situ protein synthesis on the glass arrays. All proteins were detected by using a monoclonal anti-GST antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), ensuring detection of full-length protein.

In Vitro Protein Synthesis by Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate Mixture.

In vitro protein synthesis was performed by using the TnT coupled reticulocyte lysate system kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction contained 100 ng of plasmid DNA (total) and 24 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate mix.

A549 Cell Culture and Luciferase Assay.

Human alveolar epithelial cells, A549, stably transfected with a luciferase-based NF-κB reporter construct (Panomics) were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-Glutamine and 100 μg/ml hygromycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. To measure NF-κB activation, 2 × 104 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured overnight. The next day, cells were treated with either in vitro-synthesized proteins or serial dilutions of such for 4 h. Luciferase activity was measured by using Bright-Glo luciferase assay kit (Promega) in a SpectraFluor plus plate reader (Tecan).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the members of the Harvard Institute of Proteomics for helpful discussions and for creating a stimulating environment. The genomic DNA template was kindly provided by E. Ryan (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston). This collection was produced under National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contract DHHSN266200400053C.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank (accession nos. DQ772770–DQ776221 and DQ899316–DQ899639).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0712049105/DC1.

References

- 1.Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. Cholera. Lancet. 2004;363:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoolnik GK, Yildiz FH. The complete genome sequence of Vibrio cholerae: A tale of two chromosomes and of two lifestyles. Genome Biol. 2000;1:1016.1011–1016.1013. doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-1-3-reviews1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colwell RR. Infectious disease and environment: Cholera as a paradigm for waterborne disease. Int Microbiol. 2004;7:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson FL, Iida T, Swings J. Biodiversity of vibrios. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:403–431. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.403-431.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan R, Reeves PR. Pandemic spread of cholera: Genetic diversity and relationships within the seventh pandemic clone of Vibrio cholerae determined by amplified fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:172–181. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.172-181.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piarroux R. Cholera: Epidemiology and transmission. Experience from several humanitarian interventions in Africa, Indian Ocean and Central America. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2002;95:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddique AK, et al. Why treatment centres failed to prevent cholera deaths among Rwandan refugees in Goma, Zaire. Lancet. 1995;345:359–361. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddique AK. Cholera epidemic among Rwandan refugees: Experience of ICDDR,B in Goma, Zaire. Glimpse. 1994;16:3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIAID. NIAID biodefense research agenda for category B, C priority pathogens. NIH Publication No. 03-5315. 2003:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine MM, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of recombinant live oral cholera vaccines, CVD 103 and CVD 103-HgR. Lancet. 1988;2:467–470. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenner JR, et al. Peru-15, an improved live attenuated oral vaccine candidate for Vibrio cholerae O1. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1126–1129. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richie EE, et al. Efficacy trial of single-dose live oral cholera vaccine CVD 103-HgR in North Jakarta, Indonesia, a cholera-endemic area. Vaccine. 2000;18:2399–2410. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemens JD, et al. Field trial of oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: Results of one year of follow-up. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:60–69. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan ET, Calderwood SB, Qadri F. Live attenuated oral cholera vaccines. Exp Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:483–494. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosley WH, Ahmad S, Benenson AS, Ahmed A. The relationship of vibriocidal antibody titre to susceptibility to cholera in family contacts of cholera patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38:777–785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosley WH, Benenson AS, Barui R. A serological survey for cholera antibodies in rural east Pakistan. A comparison of antibody titres in the immunized and control populations of a cholera-vaccine field-trial area and the relation of antibody titre to cholera case rate. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38:335–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmgren J, Svennerholm AM. Mechanisms of disease and immunity in cholera: A review. J Infect Dis. 1977;136(Suppl):S105–S112. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.supplement.s105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glass RI, et al. Seroepidemiological studies of El Tor cholera in Bangladesh: Association of serum antibody levels with protection. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:236–242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brizuela L, Braun P, LaBaer J. FLEXGene repository: From sequenced genomes to gene repositories for high-throughput functional biology and proteomics. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;118:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brizuela L, Richardson A, Marsischky G, LaBaer J. The FLEXGene repository: Exploiting the fruits of the genome projects by creating a needed resource to face the challenges of the post-genomic era. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:318–324. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(02)00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dricot A, et al. Generation of the Brucella melitensis ORFeome version 1.1. Genome Res. 2004;14:2201–2206. doi: 10.1101/gr.2456204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, et al. Approaching a complete repository of sequence-verified protein-encoding clones for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Res. 2007;17:536–543. doi: 10.1101/gr.6037607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudson JR, Jr, et al. The complete set of predicted genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a readily usable form. Genome Res. 1997;7:1169–1173. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.12.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuyama A, et al. ORFeome cloning and global analysis of protein localization in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:841–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy T, et al. A full-genomic sequence-verified protein-coding gene collection for Francisella tularensis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park J, et al. Building a human kinase gene repository: bioinformatics, molecular cloning, and functional validation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8114–8119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503141102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Temple G, et al. From genome to proteome: Developing expression clone resources for the human genome. Hum Mol Genet 15 Spec No. 2006;1:R31–R43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witt AE, et al. Functional proteomics approach to investigate the biological activities of cDNAs implicated in breast cancer. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:599–610. doi: 10.1021/pr050395r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murthy TV, et al. Bacterial cell-free system for high-throughput protein expression and a comparative analysis of Escherichia coli cell-free and whole cell expression systems. Protein Expression Purif. 2004;36:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaBaer J, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 gene collection. Genome Res. 2004;14:2190–2200. doi: 10.1101/gr.2482804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidelberg JF, et al. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 2000;406:477–483. doi: 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taycher E, et al. A novel approach to sequence validating protein expression clones with automated decision making. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun P, et al. Proteome-scale purification of human proteins from bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2654–2659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042684199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun P, LaBaer J. High throughput protein production for functional proteomics. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:383–388. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramachandran N, et al. Self-assembling protein microarrays. Science. 2004;305:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1097639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gewirtz AT, et al. Salmonella typhimurium induces epithelial IL-8 expression via Ca(2+)-mediated activation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:79–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayashi F, et al. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tallant T, et al. Flagellin acting via TLR5 is the major activator of key signaling pathways leading to NF-kappa B, proinflammatory gene program activation in intestinal epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2004;4:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, et al. Identification of proinflammatory flagellin proteins in supernatants of Vibrio cholerae O1 by proteomics analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2374–2383. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600228-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coster TS, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of live attenuated Vibrio cholerae O139 vaccine prototype. Lancet. 1995;345:949–952. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.