Abstract

Activation of the nuclear hormone receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (PPARδ) has been shown to improve insulin resistance, adiposity, and plasma HDL levels. However, its antiatherogenic role remains controversial. Here we report atheroprotective effects of PPARδ activation in a model of angiotensin II (AngII)-accelerated atherosclerosis, characterized by increased vascular inflammation related to repression of an antiinflammatory corepressor, B cell lymphoma-6 (Bcl-6), and the regulators of G protein-coupled signaling (RGS) proteins RGS4 and RGS5. In this model, administration of the PPARδ agonist GW0742 (1 or 10 mg/kg) substantially attenuated AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis without altering blood pressure and increased vascular expression of Bcl-6, RGS4, and RGS5, which was associated with suppression of inflammatory and atherogenic gene expression in the artery. In vitro studies demonstrated similar changes in AngII-treated macrophages: PPARδ activation increased both total and free Bcl-6 levels and inhibited AngII activation of MAP kinases, p38, and ERK1/2. These studies uncover crucial proinflammatory mechanisms of AngII and highlight actions of PPARδ activation to inhibit AngII signaling, which is atheroprotective.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ, vascular inflammation, macrophage

Renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) activation strongly promotes inflammation and oxidative stress in the arterial wall, accelerating atherosclerosis both in genetically altered atherosclerosis-prone mice and in humans (1–4). RAAS inhibition attenuates coronary artery disease (CAD) in mouse models and humans. The decreased risk of CAD and stroke is independent of blood pressure reduction, so multiple strategies to inhibit this critical system are being developed (5). However, current approaches only modestly inhibit vascular inflammation (6). Ligands to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family of nuclear receptors have potent antiinflammatory capacity. Activation of PPARγ and PPARα inhibits high-fat (HF) diet-induced atherosclerosis in mouse models, as well as in AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis (W.A.H., A.R.C., and R.K.T., unpublished observations). Although ligands of PPARδ have been reported to exert antiinflammatory effects in vitro and in vivo, their effects on vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in mouse models have been inconsistent. This issue is potentially important because PPARδ ligands have profound metabolic effects and are currently being tested in clinical trials for therapeutic effects on diabetes and obesity.

PPARδ has been implicated in the control of lipid metabolism, energy homeostasis, and obesity (7–9). Treatment with a synthetic PPARδ agonist substantially improved lipid profiles in mice and monkeys and inhibited diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by increasing the expression of genes that promote lipid catabolism and mitochondrial uncoupling (7, 9–13). Moreover, adipose tissue-specific overexpression of PPARδ prevented the development of obesity in db/db mice (9). The PPARδ ligand GW1516 was also shown to increase expression of ABCA1 and induce apoA1-specific cholesterol efflux in human THP-1 monocytes, but not in mouse cells (14–16). Despite these beneficial effects, the antiatherogenic effects of PPARδ ligands in animal models have been inconsistent (15, 17). Administration of the PPARδ ligand GW0742 in female LDLR−/− mice fed a HF diet has been shown to inhibit atherosclerosis (17). Li et al. (15), however, reported that GW0742 failed to inhibit atherosclerotic lesion development in male LDLR−/− mice on a HF diet, although both PPARα and PPARγ ligands significantly inhibited atherosclerosis (15). Furthermore, studies by Lee et al. (14) demonstrated that LDLR−/− mice transplanted with PPARδ−/− bone marrow developed less atherosclerosis than wild-type bone marrow recipient mice when fed a HF diet. These studies suggested a proatherogenic effect of unliganded PPARδ, which was reversed by a PPARδ agonist or by deletion of PPARδ. More recently this group demonstrated that GW1516 reduced atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice by raising HDL and suppressing inflammation (G.D.B., C.-H.L., and R.M.E., unpublished results). The latter action was associated with vascular induction of expression of RGS proteins, which block signal transduction activity of several chemokine receptors, which are coupled to G proteins. We therefore hypothesized that activation of PPARδ would prominently inhibit atherosclerosis in an AngII, G protein-mediated proinflammatory model of AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis. Indeed, these results may be highly relevant to the accelerated atherosclerosis associated with the metabolic syndrome, in which both adipose and vascular tissue produce AngII, which may lead to RAAS activation (18–22). We now report that PPARδ and RAAS signaling intersect. We found that AngII treatment increased PPARδ:Bcl-6 complex formation, a mechanism that has previously been proposed to attenuate Bcl-6-mediated repression of proinflammatory genes. PPARδ activation also regulates vascular RGS expression and inhibits proinflammatory and proatherogenic pathways to attenuate AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis.

Results

PPARδ Is Expressed in the Vessel Wall and Attenuates AngII-Accelerated Atherosclerosis.

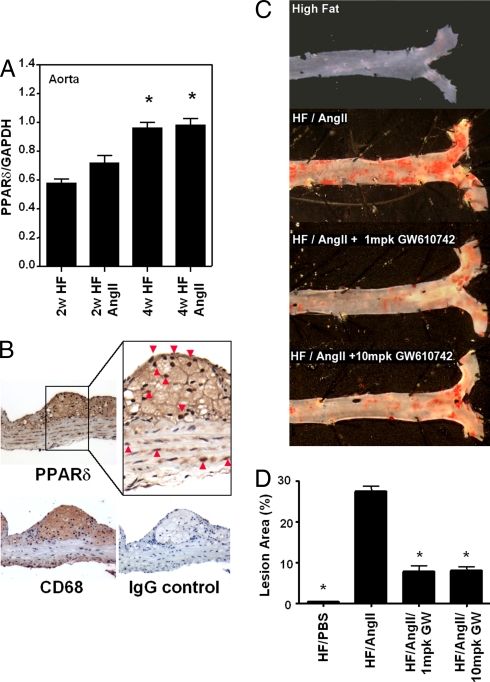

Both PPARδ mRNA and protein were expressed in the artery wall. After 4 weeks of treatment, vascular PPARδ mRNA expression was significantly increased (40%) in HF-fed mice compared with mice fed a chow diet (data not shown), but AngII infusion did not further increase PPARδ mRNA expression (Fig. 1A). However, mice treated with AngII and the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker valsartan had significantly less vascular PPARδ expression than mice treated with a HF diet or a HF diet plus AngII (data not shown). Aorta cross sections immunostained with PPARδ-specific antibodies revealed that PPARδ protein expression localized predominantly in macrophage-rich areas of atherosclerotic lesions and, to a lesser extent, in vascular smooth muscle cells in the media (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

PPARδ activation attenuates AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis. Male LDLR−/− mice were treated with HF/PBS, HF/AngII, or HF/AngII/GW0742 (1 mpk or 10 mpk) for 4 weeks. (A) Aortic PPARδ mRNA expression after 2 and 4 weeks of HF/AngII treatment. Data are mean ± SD (n = 12 per group). *, P < 0.01 vs. HF. (B) Localization of aorta PPARδ protein expression by immunohistochemistry. PPARδ protein expression localized predominantly to macrophage-rich areas (CD68-positive intimal layer) and intimal vascular smooth muscle cells in lesions. (Magnification: ×40.) (C) Representative Sudan IV-stained aortas. (D) Quantification of en face atherosclerotic lesion coverage. Data are mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). *, P < 0.01 vs. HF/AngII by ANOVA.

To investigate the effect of PPARδ activation on accelerated atherosclerosis, LDLR−/− mice were infused with AngII or PBS and fed a HF diet, with or without GW0742. At 4 weeks, AngII infusion prominently increased mean systolic blood pressure (47%) compared with PBS-infused mice, whereas GW0742 treatment had no effect on blood pressure (Table 1). The effect of PPARδ agonist on AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis was quantified by en face analysis. At 4 weeks, HF/PBS-treated mice had mean aortic atherosclerotic lesion areas of ≈2%, whereas HF/AngII-treated mice had mean lesions areas of ≈27% (Fig. 1 C and D). GW0742 treatment, at both 1 and 10 mg/kg (mpk), significantly inhibited (≈70%) AngII induction of atherosclerotic lesion area but did not alter vascular PPARδ expression.

Table 1.

Characteristics of AngII-infused HF-fed LDLR−/− mice treated with or without PPARδ ligand

| Characteristics | HF/AngII | HF/AngII/1 mpk GW | HF/AngII/10mpk GW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial BW (g) | 25.5 ± 2.2 | 26.5 ± 1.3 | 26.6 ± 1.3 |

| Final BW (g) | 21.6 ± 1.4 | 20.5 ± 1.5 | 20.1 ± 1.2 |

| Intial BP (mm Hg) | 108.0 ± 6.5 | 100.2 ± 5.9 | 103.3 ± 6.5 |

| Final BP (mm Hg) | 155.6 ± 11.6 | 168.5 ± 16.8 | 171.4 ± 14.3 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 160.0 ± 18.2 | 115.0 ± 8.5* | 65.0 ± 14.0* |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1273 ± 78.7 | 1035. ± 35.8* | 1140 ± 1.3* |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 78.0 ± 2.0 | 115.0 ± 4.3* | 48.0 ± 4.0* |

| Fatty acids (mg/dL) | 58.0 ± 2.0 | 43.0 ± 1.6* | 36.0 ± 1.9* |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 241.0 ± 16.9 | 207.0 ± 10.7 | 153.0 ± 9.6* |

| Insulin (mg/dL) | 762 ± 94 | 718 ± 109 | 575 ± 82* |

| Resistin (pg/mL) | 1483 ± 94 | 1298 ± 160 | 1112 ± 147 |

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 1041 ±72 | 397 ± 85* | 330 ± 82* |

| MCP-1 (pg/mL) | 89.0 ± 20.0 | 12.2 ± 2.0* | 12.1 ± 12.0* |

| PAI-1 (pg/mL) | 4742 ± 316 | 2337 ± 322* | 3630 ± 410 |

BW, body weight; BP, blood pressure. Means ± SD. *, P < 0.05 vs. HF/AngII.

PPARδ Ligand Treatment Improves Hypertriglyceridemia, but Not Hypercholesterolemia, and Decreases Inflammatory Adipokines.

As shown in Table 1, treatment with 1 and 10 mpk GW0742 decreased plasma triglycerides (23% and 53%, respectively) and free fatty acids (22% and 27%, respectively), without changing total plasma cholesterol levels. GW0742 treatment increased plasma HDL 24% at 1 mpk but decreased HDL 29% at the 10-mpk dose. The HDL reduction at the higher dose may be due to the profound decreases in plasma triglyceride at this dose. Fasting insulin and glucose levels decreased progressively with 1 and 10 mpk of GW0742 and were associated with decreases in plasma levels of the adipokines leptin, MCP-1, and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), but not resistin (Table 1).

Quantification of Plasma GW0742 Levels.

Plasma concentrations of GW0742 were measured in pooled plasma samples from mice fed a HF diet with or without GW0742 using liquid chromatography–tandem MS. The plasma concentrations of GW0742 in mice treated with 1 and 10 mg/kg dose were 207.78 ng/ml (440.7 nM) and 1071.9 ng/ml (2.27 mM), respectively. Notably, the plasma concentration of the ligand at the 1 mg/kg dose would be expected to specifically activate PPARδ without any cross-reactivity with other PPAR isoforms because these levels are well below the reported EC50 values for PPARα (8,900 nM) and PPARγ (>10,000 nM) (17).

PPARδ Activation Antagonizes AngII-Mediated Macrophage Recruitment and Vascular Inflammatory Gene Expression.

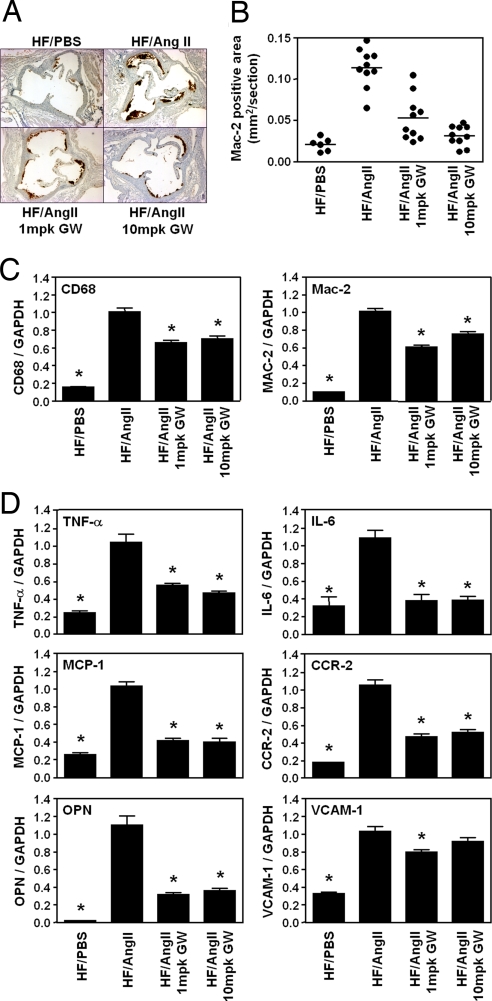

AngII strongly induces macrophage recruitment, foam cell formation, and inflammatory gene expression in the vasculature (23). PPARδ ligands increase free Bcl-6 in the macrophage, suppressing MCP-1 transcription and decreasing macrophage vascular infiltration (5, 14). At 4 weeks, atherosclerotic lesion macrophage content was markedly increased in HF/AngII vs. HF/PBS LDLR−/− mice, but GW0742 treatment reduced lesion macrophage content to levels similar to those found in HF/PBS LDLR−/− mice (Fig. 2 A and B). Furthermore, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses of these aorta demonstrated that AngII infusion increased expression of two macrophage marker genes, CD68 and Mac-2 (5.6- and 10-fold, respectively) (Fig. 2C), and that both the 1- and 10-mpk GW0742 doses markedly attenuated vascular CD68 (30% and 42%, respectively) and Mac-2 (32% and 38%, respectively) gene expression.

Fig. 2.

PPARδ activation suppresses AngII-induced vascular inflammation macrophage infiltration. (A) Macrophage abundance (Mac-2 antibody stain) in aortic root lesions. (B) Quantitative analysis of Mac-2-positive area in the aortic root lesions. (C) RT-PCR analysis of aortic expression of two macrophage markers (CD68 and Mac-2). RNA from the whole aortas was analyzed by qRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH expression. (D) PPARδ agonist inhibits AngII-induced vascular inflammation. RNA levels in the aorta were analyzed by using qRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Data are mean ± SD (n = 12 per group). *, P < 0.01 vs. HF/AngII by ANOVA.

Similarly, as shown in Fig. 2D, AngII infusion increased the vascular expression of several proinflammatory and proatherogenic genes, including TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, CCR2, VCAM-1, and osteopontin (OPN), whose expression was attenuated by GW0742 treatment (Fig. 2D). Of note, MCP-1 and its receptor CCR-2 play significant roles in atherogenesis, because mice deficient for their expression demonstrate significantly reduced diet-induced atherosclerosis (24, 25). OPN is also a critical mediator of AngII-accelerated atherosclerosis (26). GW0742 had a modest effect to decrease in VCAM-1 expression at 1 mpk and no effect on ICAM-1 (data not shown). These data demonstrate that PPARδ agonist effectively inhibits AngII-accelerated vascular inflammation and proatherogenic gene expression in the aorta.

PPARδ Activation Attenuates AngII Suppression of the Antiinflammatory Transcriptional Repressor Protein Bcl-6 in Aorta and Peripheral Macrophages.

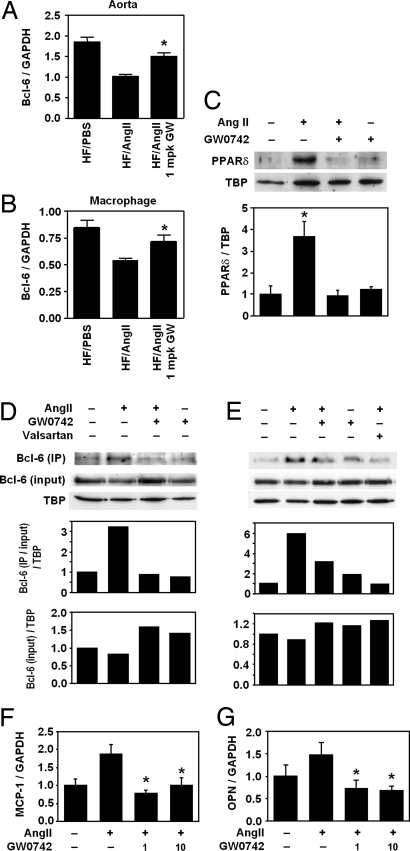

Because PPARδ ligands exert significant effects on AngII-induced inflammation and PPARδ has been demonstrated to have direct effects on the antiinflammatory transcriptional repressor Bcl-6, we examined the effect of AngII infusion on macrophage and aorta Bcl-6 expression. qRT-PCR analyses revealed that 4 weeks of AngII infusion strongly inhibited Bcl-6 expression in both whole aorta and peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 3 A and B; aorta: 45% reduction, P < 0.05; macrophages: 36% reduction, P < 0.01) and that 1-mpk GW0742 treatment significantly attenuated this inhibition in both macrophages and the aorta.

Fig. 3.

AngII suppresses Bcl-6 expression in the aorta and macrophage. RNA isolated from whole aorta (A) and peritoneal macrophages (B) was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Bcl-6 expression was normalized to GAPDH. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6–10 per group). *, P < 0.01 vs. HF/AngII by ANOVA. (C) AngII increases and PPARδ ligand decreases macrophage PPARδ protein expression. (D and E) Bcl-6 protein expression and PPARδ:Bcl-6 interaction in macrophages in response to AngII and/or GW0742. Bcl-6:PPARδ interaction was analyzed by Western blot analyses of total and PPARδ-bound Bcl-6 in macrophage nuclear proteins after pull-down assays. (F and G) MCP-1 and OPN mRNA levels in peritoneal macrophages treated with AngII and/or GW0742. Data are mean ± SD (n = 5 per group). *, P < 0.01 vs. HF/AngII by ANOVA.

To further investigate the regulation of vascular inflammatory pathways by AngII and PPARδ and the roles of Bcl-6 and PPARδ in these processes, we performed in vitro studies using mouse peritoneal macrophages. We found that macrophages treated with AngII revealed a 4-fold increase in nuclear PPARδ protein (Fig. 3C) but that pretreatment with 1 μM GW0742 completely abolished this effect. Western blot analyses of both total and PPARδ-bound Bcl-6 in macrophage nuclear extracts revealed that AngII tended to suppress total Bcl-6 but markedly increased PPARδ:Bcl-6 complexes and that both GW0742 and valsartan pretreatment decreased PPARδ:Bcl-6 binding (Fig. 3 D and E). These data demonstrate that AngII can increase nuclear PPARδ:Bcl-6 binding, limiting the amount of free Bcl-6 to repress the expression of inflammatory genes normally suppressed by Bcl-6. Valsartan pretreatment greatly attenuated PPARδ:Bcl-6 binding, indicating that this effect of AngII is mediated by the angiotensin type 1 (AT-1) receptor, which mediates most of the proinflammatory actions of AngII (27). Consistent with the change in free Bcl-6, AngII-stimulated MCP-1 expression, which is known to be regulated by Bcl-6 (28), was attenuated by GW0742 (Fig. 3F). Similar gene expression changes were also seen for the macrophage chemoattractant OPN (Fig. 3G).

PPARδ Ligand Inhibits AngII-Induced Activation of MAP Kinases.

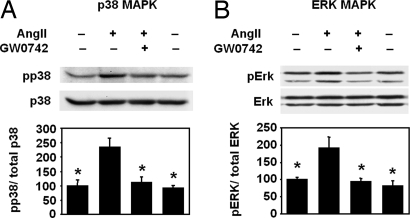

Because AngII is known to activate MAP kinase intracellular signaling pathways to promote vascular inflammation and macrophage recruitment (27, 29), we examined whether PPARδ activation alters AngII-mediated activation of MAP kinase pathways in macrophages. We found that in mouse peritoneal macrophages AngII treatment stimulated a 2-fold increase in the phosphorylation of both the p38 and ERK1/2 MAP kinases (Fig. 4). GW0742 treatment completely abolished AngII-stimulated p38 and ERK1/2 MAP kinase phosphorylation, indicating that GW0742 has inhibitory effects on MAP kinase activity in macrophages.

Fig. 4.

PPARδ activation inhibits AngII-induced phosphorylation of MAP kinases. Mouse peritoneal macrophages stimulated with AngII in the presence or absence of GW0742 were analyzed by Western blot for MAP kinase activation. Activation of p38 (A) and ERK1/2 (B) was measured by the levels of phosphorylated p38 (pp38) and ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) normalized to total p38 and ERK1/2. n = 3 per group. *, P < 0.05 vs. AngII by ANOVA.

PPARδ Inhibition of AngII Signaling Requires RGS5, a Key Regulator of G Protein Signaling, to Inhibit AngII-Mediated MAPK Activation.

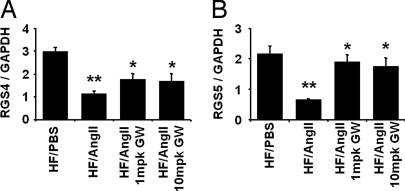

To determine whether PPARδ regulates components of AngII signaling, we examined the effects of AngII infusion on aortic expression of the two key regulators of G protein-coupled receptor signaling, RGS4 and RGS5, in LDLR−/− mice fed a HF diet. AngII infusion for 4 weeks significantly suppressed aorta RGS4 and RGS5 mRNA levels, and this inhibition was substantially blocked by pretreatment with GW0742 (Fig. 5). Because AngII effects can be modulated by RGS5, which attenuates G protein receptor signaling in the vasculature, we further examined whether RGS5 attenuation affects the ability of GW0742 to inhibit AngII-mediated MAPK activation. RGS5 knockdown with RGS5-specific siRNA in mouse peritoneal macrophages almost completely inhibited GW0742 suppression of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by AngII, whereas control siRNA had no effect [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. Furthermore, RGS5 knockdown in macrophages resulted in a substantial increase in both basal and AngII-induced c-fos mRNA levels, which were no longer attenuated by GW0742 (SI Fig. 6). These data indicate that PPARδ attenuation of AngII-mediated signaling is regulated at least in part by RGS5.

Fig. 5.

PPARδ activation inhibits AngII-mediated G protein signaling and suppression of RGS4 and RGS5 in macrophages. AngII infusion inhibits aorta RGS4 (A) and RGS5 (B) expression, and this effect is reversed by GW0742. Aorta RNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR, and RGS4 and RGS5 mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH. Data are mean ± SD (n = 5 per group). *, P < 0.001 vs. HF/PBS; **, P < 0.05 vs. HF/AngII (by ANOVA).

Discussion

The dynamic balance between lipid homeostasis and inflammation is critical to the atherogenic process and, thus, likely predicts the potential atheroprotective effects of PPAR ligands. Because PPARδ ligands demonstrate consistent antiinflammatory effects, we postulated that PPARδ ligands could significantly attenuate atherosclerosis in a proinflammatory model of accelerated atherosclerosis by decreasing vascular inflammation. Genetic and pharmacologic approaches that alter PPARδ activation have, however, produced diverse effects on hyperlipidemia-driven models of atherosclerosis. Paradoxically, both PPARδ activation with GW501516 and macrophage-specific PPARδ deficiency are reported to attenuate macrophage-elicited inflammation, and LDLR−/− mice transplanted with PPARδ−/− bone marrow demonstrate reduced atherogenesis (14). Similarly, Li et al. (15) reported that 5 mpk of GW0742 suppressed vascular inflammatory gene expression but failed to attenuate atherosclerosis in male LDLR−/− mice fed a HF diet, whereas Graham et al. (17) found that GW0742 modestly inhibited atherosclerosis (30%) in female LDLR−/− mice fed a HF diet. GW0742 had no effect on atherosclerotic lesion expression of macrophage markers in either study. By contrast, in the present study, both 1 and 10 mpk of GW0742 substantially inhibited macrophage content and attenuated the extent of atherosclerosis in an AngII-infused HF-fed male LDLR−/− mouse model of accelerated atherosclerosis. A major reason for the potent atheroprotective effect of the PPARδ ligand in this proinflammatory model, in contrast to previous HF dietary mouse models, appears to be its prominent effects on vascular inflammation and macrophage recruitment into the artery wall.

We and others have shown that AngII infusion profoundly increases inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic LDLR−/− mice (30). However, despite a HF diet and the resulting changes in their lipid parameters, these mice do not develop obesity and type 2 diabetes. In the present investigation we demonstrate both mechanisms for the proinflammatory actions of AngII and an antiatherogenic mechanism through which PPARδ activation can suppress AngII-induced inflammation. We found that the PPARδ ligand GW0742 substantially inhibited vascular proinflammatory gene expression, macrophage recruitment, foam cell formation, and atherosclerosis in AngII-infused male LDLR−/− mice fed a HF diet. AngII infusion also increased PPARδ expression and reduced Bcl-6 expression in the aorta of this mouse model. Moreover, in vitro studies with mouse peritoneal macrophages showed that AngII suppressed both total and free Bcl-6, which was associated with both increased MCP-1 and OPN production, and that GW0742 reversed all of these effects.

We have previously demonstrated that macrophage OPN is essential for AngII acceleration of atherosclerosis, because mice transplanted with bone marrow lacking OPN had both decreased macrophage infiltration and enhanced macrophage apoptosis leading to decreased vessel accumulation of macrophage foam cells (26). In the present study, the effect of GW0742 to decrease aortic OPN and MCP-1 expression, which leads to decreased macrophage accumulation, likely contributes to its antiatherosclerotic effects. In recent studies, we found that AngII-infused LDLR−/− mice transplanted with PPARδ−/− bone marrow have increased aortic OPN and MCP-1 expression compared with wild-type control mice and that PPARδ ligand treatment does not affect these genes in the absence of macrophage PPARδ (R.K.T., A.R.C., and W.A.H., unpublished results). These observations suggest that at least a subset of ligand effects depends on macrophage PPARδ.

In this study we also provide evidence that AngII modulates RGS4 and RGS5 expression in the aorta. RGS proteins play important roles in the regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling by binding to the active G subunits and stimulating GTP hydrolysis, thus switching off G protein signaling (31). Both RGS4 and RGS5 have been reported to be negative regulators of AngII signaling through the AT1 receptor (32, 33), suggesting that AngII can enhance its own signaling by down-regulating RGS4 and RGS5. Barish et al. have shown that PPARδ ligands increase RGS4 and RGS5 expression in the aorta (7, 34). Similarly, we found that GW0742 prevented the AngII-induced down-regulation of RGS4 and RGS5 in the aorta and inhibited AngII activation of macrophage p38 and ERK1/2 MAP kinases, as well as downstream c-fos activation (data not shown). Furthermore, RGS5 siRNA inhibited PPARδ attenuation of AngII-induced activation of p38 and ERK1/2 MAP kinases in mouse peritoneal macrophages and increased c-fos expression, suggesting that the antiinflammatory effect of PPARδ is partially mediated by RGS5 activity. Significantly, c-fos binding to AP-1 elements is known to enhance expression of a variety of proinflammatory genes, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1, which we found to be down-regulated in the aorta of these mice by GW0742. Thus, these results underscore a mutually antagonistic relationship between AngII and PPARδ activation on inflammatory processes and demonstrate the physiologic relevance of these novel relationships in vivo.

AngII infusion significantly increased aorta PPARδ expression, which localized predominantly to macrophage-rich lesions and vascular smooth muscle cells. Unliganded PPARδ, which is considered to be proatherogenic, binds Bcl-6, reducing the amount of free Bcl-6 available to suppress MCP-1 transcription and resulting in increased MCP-1 expression (14, 35). In mouse peritoneal macrophages, AngII decreased free Bcl-6 by (i) decreasing Bcl-6 expression, (ii) increasing PPARδ levels, and (iii) augmenting the fraction of Bcl-6 bound to PPARδ. AngII-induced reductions in free Bcl-6 were associated with increased macrophage MCP-1 and OPN expression, suggesting that Bcl-6 regulates both OPN and MCP-1 expression, especially because mouse macrophages deficient in Bcl-6 express higher levels of OPN and MCP-1 (G.D.B., R.K.T., W.A.H., and R.M.E., unpublished results).

PPARδ activation has been suggested to induce ABCA1 and ABCG1, key genes in the process of reverse cholesterol transport (7, 12, 36). However, the overall impact of PPARδ activation in macrophage cholesterol homeostasis remains controversial. The PPARδ ligand GW501516 was reported to increase expression of ABCA1 and induce apoAI-specific cholesterol efflux from human THP-1 cells. Vosper et al. (37) showed that another PPARδ ligand induced expression of scavenger receptors (SR-A and CD36) involved in lipid accumulation in macrophages. We observed no changes in LXRα, ABCA1, ABCG1, or CD36 expression in aorta or peritoneal macrophages after GW0742 treatment (data not shown). Consistent with our data, Lee et al. (14) demonstrated that neither PPARδ deletion nor activation affected macrophage cholesterol efflux or accumulation. Similarly, data from Li et al. (15) also suggest that PPARδ has no significant role in macrophage cholesterol homeostasis. Based on these data, PPARδ appears to mediate its antiatherogenic effects predominantly through inhibition of vascular inflammation and macrophage recruitment rather than through regulation of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis.

These results underscore the antiinflammatory actions of PPARδ that, via regulation of Bcl-6 expression and the RGS pathway, work in concert to inhibit AngII-induced atherosclerosis. Current approaches to RAAS inhibition include direct renin inhibition, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition, AT1 receptor blockade, and mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition. These approaches are often used in combination for added clinical benefit (38). It has been suggested that obese subjects have increased RAAS activity, in part because of increased angiotensin secretion from adipose tissue, which may contribute to hypertension and the metabolic syndrome (18, 19, 22). The actions of PPARδ activation to promote weight loss, increase energy expenditure, promote insulin sensitivity, and improve dislipidemia, as well as its newly identified action to inhibit AngII-induced inflammation, make it an attractive therapeutic target for the metabolic syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Animal Experiments.

LDLR−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice (3 months of age) were fed a chow diet, a HF diet (Western Diet D12079B; protein, 17 kcal%; carbohydrate, 43 kcal%; fat, 41 kcal%; Research Diets), or a HF diet supplemented with the synthetic PPARδ agonist GW0742 (1 or 10 mpk per day, kindly provided by GlaxoSmithKline) for 4 weeks. GW0742 is a highly potent and selective PPARδ agonist with an EC50 value of 50 nM for mouse PPARδ compared with 8,900 nM for mouse PPARα and >10,000 nM for mouse PPARγ (17). Mice were infused with AngII or PBS through s.c. implantation of osmotic minipumps (Alza) containing AngII (2.5 μg/kg per minute) in PBS or PBS alone for 4 weeks. Blood pressure was measured weekly for the duration of the study. All animal procedures were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles, Animal Research Committee. Plasma samples were collected after overnight fasting. Total cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, and free fatty acids were analyzed by using enzymatic methods (Wako Chemicals). Blood glucose was measured by a one-touch glucose monitoring system. Insulin and adipokines were measured by using ELISA kits (Linco). Plasma concentrations of GW0742 were measured from pooled mouse plasma by using liquid chromatography–tandem MS as described by Barish et al. (7), with minor modifications.

Quantification of Atherosclerosis and Immunohistochemistry.

Mice were killed and perfused with 7.5% sucrose in paraformaldehyde. Aortas were dissected, pinned out, and stained with Sudan IV. Images were captured with a Sony 3-CCD video camera and analyzed by using ImagePro image analysis software. The extent of lesion development is expressed as the percentage of the total aortic surface covered by lesions (39). Aortic immunocytochemical analyses were performed with antibodies specific for Mac-2, CD68, and PPARδ.

Reverse Transcription and qRT-PCR.

PPARδ, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, CCR2, OPN, CD44, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, CD68, and Mac-2 mRNA expression in the whole aorta was measured by using qRT-PCR. The RNA from the whole aorta was isolated 4 weeks after treatment by using RNeasy kit DNase (Qiagen), then reverse-transcribed into cDNA by using a TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagent kit (Applied Biosystems) and a TaqMan PCR Core Reagent Kit (Applied Biosystems). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and normalized to values for GAPDH mRNA expression by using TaqMan Rodent GAPDH Control Reagent (Applied Biosystems).

Macrophage Isolation and Treatment.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages were isolated 4 days after injection of 4% thioglycolate. Cells were seeded in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS for 4 h and then rinsed and then maintained in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 0.4% FBS for 24–48 h. After pretreatment with GW0742 for 1 h, the cells were stimulated with AngII for 15 min for MAP kinase phosphorylation studies or for 48 h for Bcl-6–PPARδ protein expression and interactions.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analyses.

To examine interactions between PPARδ and Bcl-6, nuclear protein was isolated from mouse peritoneal macrophages after treatments as described by using a Nuclear Extraction Kit from Panomics. Nuclear protein was immunoprecipitated with an anti-PPARδ antibody (Afffinity Bioreagents) for 1.5 h at 4°C. The nuclear protein–antibody complex was then incubated with magnetized Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 45 min at room temperature. After extensive washing of the beads, bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by Western blot. For MAPK phosphorylation studies, whole-cell lysates were prepared from cells treated as described and Western blot analyses were performed. The levels of p38 and ERK phosphorylation were measured by using anti-phospho-p38 and anti-phospho-ERK antibodies by chemiluminescence detection (Cell Signaling Technology). Bcl-6 and PPARδ protein expression levels were determined by Western blot analyses using anti-PPARδ antibody (Affinity Bioreagents) and an anti-Bcl-6 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The immunoblots were hybridized with anti-TATA binding protein antibody (Abcam) to monitor equivalent loading in different lanes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Drs. William R. Oliver, Jr., and Timothy M. Willson of GlaxoSmithKline for GW0742 and Longsheng Hong and Diana Becerra for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant (to W.A.H.). Y.T. was supported by a Japan Heart Foundation/Novartis research grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0708647105/DC1.

References

- 1.Halkin A, Keren G. Potential indications for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Am J Med. 2002;112:126–134. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss D, Kools JJ, Taylor WR. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension accelerates the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:448–454. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1605–1612. doi: 10.1172/JCI7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dol F, et al. Angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonist irbesartan decreases lesion size, chemokine expression, and macrophage accumulation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38:395–405. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandona P, Dhindsa S, Ghanim H, Chaudhuri A. Angiotensin II and inflammation: The effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockade. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:20–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng ZJ, Vapaatalo H, Mervaala E. Angiotensin II and vascular inflammation. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:RA194–RA205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barish GD, Narkar VA, Evans RM. PPAR delta: A dagger in the heart of the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:590–597. doi: 10.1172/JCI27955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka T, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta induces fatty acid beta-oxidation in skeletal muscle and attenuates metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15924–15929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306981100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YX, et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell. 2003;113:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CH, et al. PPARdelta regulates glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3444–3449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511253103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luquet S, et al. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta (PPARdelta) in the control of fatty acid catabolism. A new target for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Biochimie. 2004;86:833–837. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muscat GE, Dressel U. Cardiovascular disease and PPARdelta: Targeting the risk factors. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:887–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y, Hon M, Evans RM. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta, an integrator of transcriptional repression and nuclear receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2613–2618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CH, et al. Transcriptional repression of atherogenic inflammation: Modulation by PPARdelta. Science. 2003;302:453–457. doi: 10.1126/science.1087344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li AC, et al. Differential inhibition of macrophage foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis in mice by PPARalpha, beta/delta, and gamma. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1564–1576. doi: 10.1172/JCI18730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver WR, Jr, et al. A selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonist promotes reverse cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5306–5311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091021198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham TL, Mookherjee C, Suckling KE, Palmer CN, Patel L. The PPARdelta agonist GW0742X reduces atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper ME. The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in diabetes and its vascular complications. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:16S–20S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.004. quiz A12–A14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorzelniak K, Engeli S, Janke J, Luft FC, Sharma AM. Hormonal regulation of the human adipose-tissue renin-angiotensin system: Relationship to obesity and hypertension. J Hypertens. 2002;20:965–973. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200205000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribichini F, et al. Cellular immunostaining of angiotensin-converting enzyme in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schieffer B, et al. Expression of angiotensin II and interleukin 6 in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques: Potential implications for inflammation and plaque instability. Circulation. 2000;101:1372–1378. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma AM. Is there a rationale for angiotensin blockade in the management of obesity hypertension? Hypertension. 2004;44:12–19. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000132568.71409.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:C82–C97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boring L, Gosling J, Cleary M, Charo IF. Decreased lesion formation in CCR2−/− mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:894–897. doi: 10.1038/29788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu L, et al. Absence of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 reduces atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Mol Cell. 1998;2:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruemmer D, et al. Angiotensin II-accelerated atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation is attenuated in osteopontin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1318–1331. doi: 10.1172/JCI18141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higuchi S, et al. Angiotensin II signal transduction through the AT1 receptor: Novel insights into mechanisms and pathophysiology. Clin Sci (London) 2007;112:417–428. doi: 10.1042/CS20060342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toney LM, et al. BCL-6 regulates chemokine gene transcription in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:214–220. doi: 10.1038/79749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunyady L, Catt KJ. Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:953–970. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takata Y, et al. Transcriptional repression of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 gene in macrophages: A novel atherosclerotic effect of angiotensin II. Circ Res. 2005;97:e88–e96. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190400.46267.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wieland T, Mittmann C. Regulators of G-protein signalling: Multifunctional proteins with impact on signalling in the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;97:95–115. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho H, Harrison K, Schwartz O, Kehrl JH. The aorta and heart differentially express RGS (regulators of G-protein signalling) proteins that selectively regulate sphingosine 1-phosphate, angiotensin II, and endothelin-1 signalling. Biochem J. 2003;371:973–980. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Liu M, Mullah B, Siderovski DP, Neubig RR. Receptor-selective effects of endogenous RGS3 and RGS5 to regulate mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24949–24958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, et al. Regulator of G protein signaling 5 marks peripheral arterial smooth muscle cells and is downregulated in atherosclerotic plaque. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plutzky J. Medicine. PPARs as therapeutic targets: Reverse cardiology? Science. 2003;302:406–407. doi: 10.1126/science.1091172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marx N, Duez H, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and atherogenesis: Regulators of gene expression in vascular cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:1168–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127122.22685.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vosper H, et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta promotes lipid accumulation in human macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44258–44265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasparo MD. New basic science initiatives with the angiotensin II receptor blocker valsartan. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1:3–5. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. Quantitation of atherosclerosis in murine models: Correlation between lesions in the aortic origin and in the entire aorta, and differences in the extent of lesions between sexes in LDL receptor-deficient and apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.