Abstract

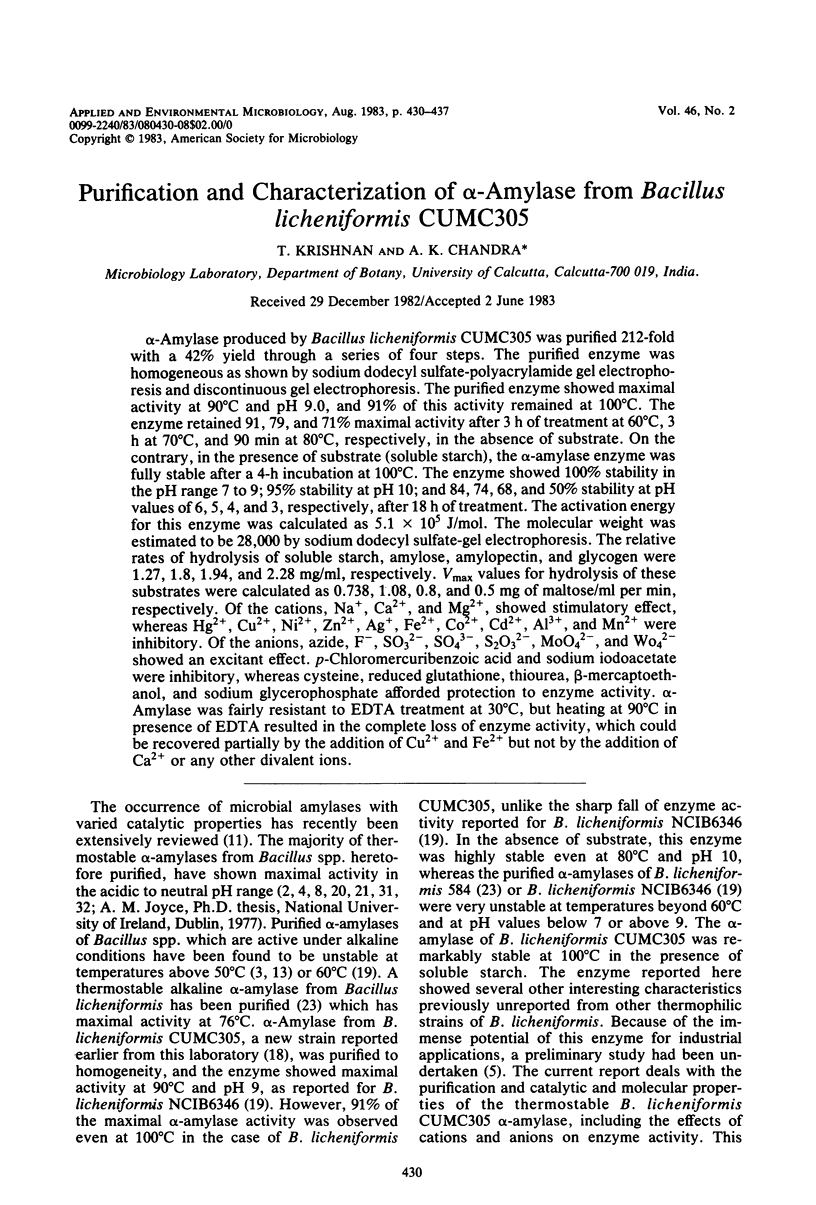

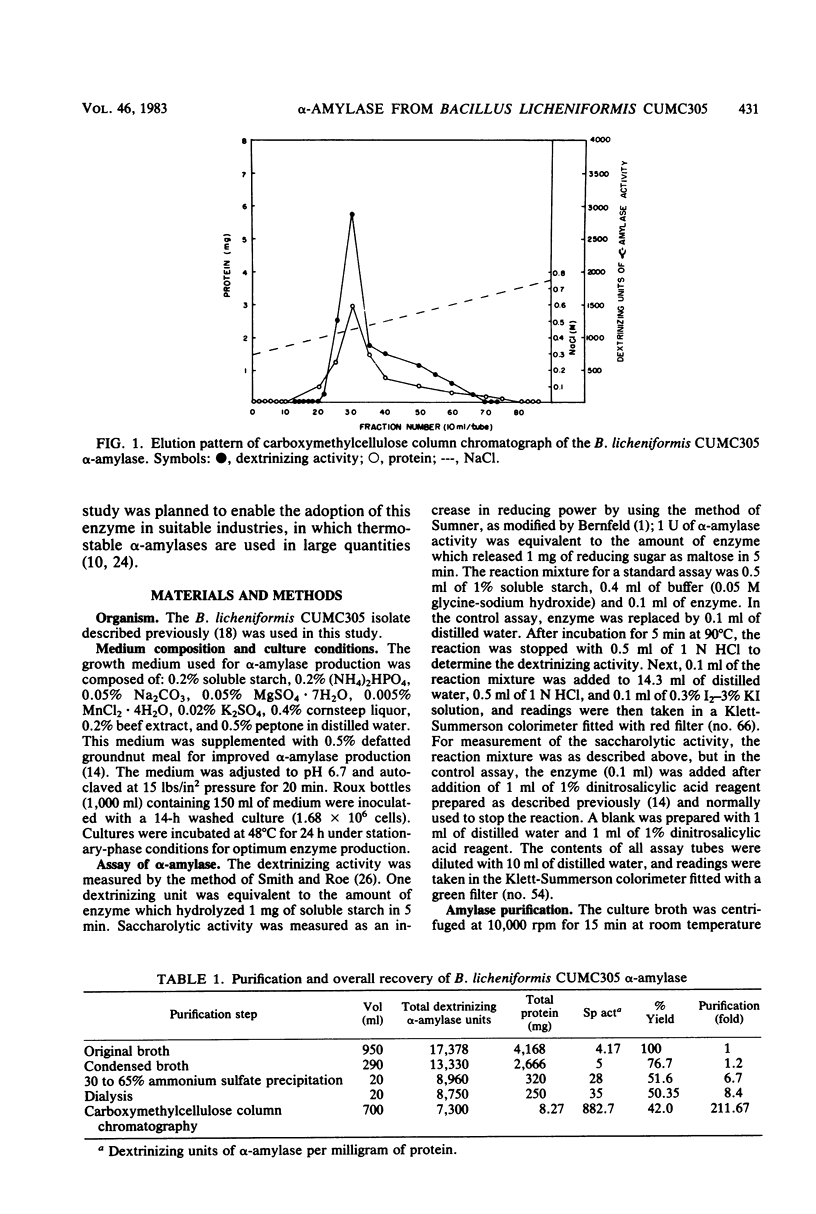

α-Amylase produced by Bacillus licheniformis CUMC305 was purified 212-fold with a 42% yield through a series of four steps. The purified enzyme was homogeneous as shown by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and discontinuous gel electrophoresis. The purified enzyme showed maximal activity at 90°C and pH 9.0, and 91% of this activity remained at 100°C. The enzyme retained 91, 79, and 71% maximal activity after 3 h of treatment at 60°C, 3 h at 70°C, and 90 min at 80°C, respectively, in the absence of substrate. On the contrary, in the presence of substrate (soluble starch), the α-amylase enzyme was fully stable after a 4-h incubation at 100°C. The enzyme showed 100% stability in the pH range 7 to 9; 95% stability at pH 10; and 84, 74, 68, and 50% stability at pH values of 6, 5, 4, and 3, respectively, after 18 h of treatment. The activation energy for this enzyme was calculated as 5.1 × 105 J/mol. The molecular weight was estimated to be 28,000 by sodium dodecyl sulfate-gel electrophoresis. The relative rates of hydrolysis of soluble starch, amylose, amylopectin, and glycogen were 1.27, 1.8, 1.94, and 2.28 mg/ml, respectively. Vmax values for hydrolysis of these substrates were calculated as 0.738, 1.08, 0.8, and 0.5 mg of maltose/ml per min, respectively. Of the cations, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, showed stimulatory effect, whereas Hg2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Ag+, Fe2+, Co2+, Cd2+, Al3+, and Mn2+ were inhibitory. Of the anions, azide, F−, SO32−, SO43−, S2O32−, MoO42−, and Wo42− showed an excitant effect. p-Chloromercuribenzoic acid and sodium iodoacetate were inhibitory, whereas cysteine, reduced glutathione, thiourea, β-mercaptoethanol, and sodium glycerophosphate afforded protection to enzyme activity. α-Amylase was fairly resistant to EDTA treatment at 30°C, but heating at 90°C in presence of EDTA resulted in the complete loss of enzyme activity, which could be recovered partially by the addition of Cu2+ and Fe2+ but not by the addition of Ca2+ or any other divalent ions.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Borgia P. T., Campbell L. L. alpha-amylase from five strains of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens: evidence for identical primary structures. J Bacteriol. 1978 May;134(2):389–393. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.2.389-393.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer E. W., Ingle M. B. Extracellular alkaline amylase from a Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1972 Jun;110(3):992–1000. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.3.992-1000.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore V., Caporale C., De Rosa M., Gambacorta A. Stable, inducible thermoacidophilic alpha-amylase from Bacillus acidocaldarius. J Bacteriol. 1976 Nov;128(2):515–521. doi: 10.1128/jb.128.2.515-521.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS B. J. DISC ELECTROPHORESIS. II. METHOD AND APPLICATION TO HUMAN SERUM PROTEINS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1964 Dec 28;121:404–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb14213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePinto J. A., Campbell L. L. Purification and properties of the amylase of Bacillus macerans. Biochemistry. 1968 Jan;7(1):114–120. doi: 10.1021/bi00841a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan T., Chandra A. K. Effect of oilseed cakes on alpha-amylase production by Bacillus licheniformis CUMC305. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Aug;44(2):270–274. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.2.270-274.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medda S., Chandra A. K. New strains of Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus coagulans producing thermostable alpha-amylase active at alkaline pH. J Appl Bacteriol. 1980 Feb;48(1):47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1980.tb05205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasahara K., Imanishi A., Isemura T. Studies on thermophilic alpha-amylase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. I. Some general and physico-chemical properties of thermophilic alpha-amylase. J Biochem. 1970 Jan;67(1):65–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a129235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfueller S. L., Elliott W. H. The extracellular alpha-amylase of bacillus stearothermophilus. J Biol Chem. 1969 Jan 10;244(1):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robyt J. F., Ackerman R. J. Structure and function of amylases. II. Multiple forms of bacillus subtilis -amylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1973 Apr;155(2):445–451. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda H., Narita K. Correlation of the sulfhydryl group with the essential calcium in Bacillus subtilis saccharifying alpha-amylase. J Biochem. 1968 Mar;63(3):302–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda H., Narita K. Replacement of the essential calcium in Taka-amylase A with other divalent cations. J Biochem. 1967 Dec;62(6):767–768. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker N. E., Campbell L. L. Comparison of the alpha-amylase of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1967 Oct;94(4):1131–1135. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.4.1131-1135.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker N. E., Campbell L. L. Unrelatedness of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1967 Oct;94(4):1124–1130. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.4.1124-1130.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]