Abstract

Current conceptualizations of psychological distance (e.g., construal-level theory) refer to the degree of overlap between the self and some other person, place, or point in time. We propose a complementary view in which perceptual and motor representations of physical distance influence people’s thoughts and feelings without reference to the self, extending research and theory on the effects of distance into domains where construal-level theory is silent. Across four experiments, participants were primed with either spatial closeness or spatial distance by plotting an assigned set of points on a Cartesian coordinate plane. Compared with the closeness prime, the distance prime produced greater enjoyment of media depicting embarrassment (Study 1), less emotional distress from violent media (Study 2), lower estimates of the number of calories in unhealthy food (Study 3), and weaker reports of emotional attachments to family members and hometowns (Study 4). These results support a broader conceptualization of distance-mediated effects on judgment and affect.

Can the relative placement of salt and pepper shakers on one’s table influence feelings of emotional attachment to one’s dinner companion? People often look to their environment for clues for how they should feel, as a natural part of the situational appraisal process (e.g., Lazarus, 1991; Trope, 1986). Indeed, those who practice feng shui believe that the placement of objects within a room, and the space between them, can directly affect people’s mental lives (e.g., Darby, 2007). A cluttered room, with insufficient space between objects, is believed to clutter one’s thoughts, whereas a room where there is ordered space between objects is believed to keep one’s thoughts clear. Is this simply mysticism, or can the amount of space between objects genuinely affect people’s judgments and feelings? Informed by theories of embodiment and conceptual development, the present research examined the power of physical-distance cues to moderate people’s emotional experiences.

A NEW LOOK AT PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTANCE

The main framework of current theorizing about the nature of psychological distance is construal-level theory (CLT; Trope & Liberman, 2003). Research guided by this theory indicates that people think about distant events more abstractly and proximal events more concretely (Liberman & Trope, 1998; Trope & Liberman, 2003). Recent research has shown construal-level differences associated with various forms of psychological distance, such as social distance inherent in power hierarchies and spatial distance between one’s current and other locations (Fujita, Henderson, Eng, Trope, & Liberman, 2006; Smith & Trope, 2006). When people feel more powerful, they tend to think more abstractly (Smith & Trope, 2006). Similarly, when people think about an event that occurs near where they live, their mental representations of the event are concrete, but when they think about an event that occurs far away, their mental representations of that event are abstract (Fujita et al., 2006). It is important to note that these effects involve the self as a reference point vis-á-vis some other place, person, or point in time.

Although construal-level theorists contend that temporal, social, and spatial distance are all contained under the umbrella of “psychological distance” (Liberman, Trope, & Stephan, in press; Trope & Liberman, 2003), we argue that spatial distance is not simply a derivative of psychological distance. Indeed, it is very much the other way around. Spatial concepts such as “nearfar” are among the first concepts available to preverbal children (Clark, 1973; Mandler, 1992), being present at 3 to 4 months of age (Leslie, 1982). Spatial relations are easy for infants to parse because the relevant information is readily available to the senses, whereas abstract concepts related to internal states are more difficult to understand (Mandler, 1992). For developing children, analyzing visual displays is much easier than analyzing their own internal states; indeed, accurate introspection is often difficult for adults (e.g., Wilson, 2002). Accordingly, we argue that a primitive understanding of physical distance is the foundation for the later-developed concept of psychological distance, given humans’ “pervasive tendency to conceptualize the mental world by analogy to the physical world, rather than the other way around” (Mandler, 1992, p. 596).

Evidence for the metaphoric application of spatial concepts was obtained by Boroditsky (2000), who showed that activating spatial concepts such as “forward” and “up” influenced judgments in the more abstract domain of temporal relations. Further, recent studies in embodied social cognition have shown effects of spatial metaphors on judgments. Judgments of the affective valence of words are facilitated when positive words are presented in the upper half of a computer screen and negative words are presented in the lower half (“up” is “good,” “down” is “bad”; Meier & Robinson, 2004; see also Clark, 1973). Also, people are more likely to understand two objects as being in a power relationship if they are aligned vertically rather than horizontally (i.e., one’s power over another; Schubert, 2005). These phenomena demonstrate how knowledge about physical relations is projected onto other domains as an analogical means of understanding them, as theorized by Lakoff and Johnson (1980) and other researchers (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002).

If physical-distance concepts are used as the analogical bridge for the development of the concept of psychological distance (Mandler, 1992), then physical distance broadly defined (i.e., not only when the self is the reference point) should influence people’s judgments and affective states. This should be the case because physical-distance cues have adaptive significance, a point that has been argued by major theorists in psychology over the past century.

Spatial distance and affect are inextricably linked, because the principle that “distance equals safety” is deeply ingrained in humans’ biological makeup. Both Tolman (1932), in his pioneering work on cognitive maps in animals, and the evolutionary epistemologist Campbell (1956, 1960) suggested that vision itself was an adaptation, enabling safer exploration of the environment at a distance by removing the need for physical contact with unknown, potentially dangerous objects and organisms. And in his classic work on attachment, Bowlby (1969) noted that maintaining specific distance relations is critical for the survival of animals and humans. In particular, he emphasized the adaptive value of the infant keeping close to its mother and monitoring its distance to her at all times in order to gain protection from predators (see also Lorenz, 1962). Finally, recent findings in cognitive neuroscience confirm that sensitivity to physical-distance information is built into the design and function of the human brain, with information processing shifting from forebrain to midbrain regions as a function of the spatial distance between oneself and a looming threat (Mobbs et al., 2007).

Our account of the importance of physical-distance information is in harmony with major theories of early concept and social development (e.g., Bowlby, 1969; Clark, 1973; Mandler, 1992). Two important implications follow. First, the activation of spatial representations of physical closeness and distance (i.e., between any two objects, without reference to the self) should influence people’s subjective experiences. Second, the activation of spatial-distance concepts should moderate the emotional impact of subsequent stimuli, because of the adaptive significance of physical-distance relations between oneself, one’s caretakers, and potential predators. Critically, neither prediction follows from CLT’s treatment of spatial distance.

In the studies reported here, we examined the effects of spatial cues on people’s affective responses to and evaluations of emotionally evocative stimuli associated with either potential harm or safety. We hypothesized that participants’ subjective experience will differ depending on whether they perceive relatively close or relatively distant points in Cartesian space. In Studies 1 and 2, we examined the effects of this physical-distance manipulation on responses to embarrassing and violent media. In Study 3, we expanded our investigation by examining the effects of the distance manipulation on judgments concerning potentially dangerous, unhealthy food. Finally, in a stringent test of the power of the physical-distance manipulation, in Study 4, we assessed its effects on participants’ self-reported emotional attachments to significant people and places in their lives.

STUDY 1

In this study, participants were primed with spatial closeness or spatial distance using a Cartesian-plane coordinate system. They then read an embarrassing book excerpt and rated the extent to which they liked the excerpt. We hypothesized that participants primed with distance would like the embarrassing story more, and those primed with closeness would like the story less, compared with people primed with an intermediate amount of distance.

Method

Participants

Seventy-three undergraduates (41 female, 32 male) were randomly assigned to the three spatial-prime conditions.

Materials and Procedure

As a cover story, participants were told that the experimenters were interested in obtaining feedback on materials for a new type of standardized test. To produce spatial-distance cues, we asked participants to mark off two points on a Cartesian plane (see Fig. 1). Each participant was given one of three sets of coordinates, which served as the closeness, intermediate, or distance prime. The set of coordinates for the closeness prime, (2, 4) and (-3, -1), were close to each other on the coordinate plane. The coordinates for the distance prime, (12, 10) and (-11, -8), were far from each other on the coordinate plane. The coordinates for the intermediate prime, (8, 3) and (-6, -5), were roughly halfway between those used for the closeness and distance primes. In other words, within the frame of the Cartesian plane, the points used in the closeness manipulation were relatively close to each other, and the points used in the distance manipulation were relatively far apart.

Fig. 1.

The grid used for spatial priming. Participants were told, “Please locate the following points on this grid.” The coordinates were (2, 4) and (-3, -1) in the closeness condition, (8, 3) and (-6, -5) in the intermediate condition, and (12, 10) and (-11, -8) in the distance condition.

Afterward, participants read an excerpt, taken from the book Good in Bed (Weiner, 2001), that depicted embarrassment. In this excerpt, the protagonist discovers a magazine article written about her. The article, titled “Loving a Larger Woman,” was written by the protagonist’s ex-boyfriend.

Participants answered three questions that assessed the extent to which they liked the excerpt. Each response was made using a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely). Specifically, participants were asked: “How much did you enjoy the passage?” “How interested might you be in reading more of the story that the passage is from?” and “Did you find the passage entertaining?” Responses to these three items were averaged into a reliable index of liking (α = .88).

Finally, participants were probed for suspicion using the funneled debriefing technique (Bargh & Chartrand, 2000). Three participants indicated suspicion that the Cartesian-plane task primed notions of distance (though they showed no awareness of the study’s hypothesis); their data were removed from the analyses.

Results and Discussion

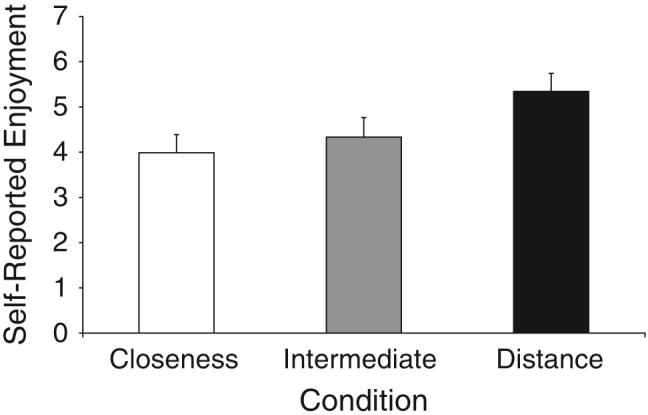

Do spatial cues influence the extent to which people enjoy an embarrassing story? As Figure 2 shows, participants primed with spatial distance enjoyed the excerpt more than those primed with spatial closeness. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the three groups differed significantly in how much they liked the embarrassing story, F(2, 67) = 3.14, prep = .88, η2 = .09. Next, we conducted a planned contrast analysis using weights of -1, 0, and 1 for a linear contrast, and -1, +2, -1 for a quadratic contrast, for the closeness, intermediate, and distance conditions, respectively. These contrast weights allowed us to test the specific hypothesis that participants in the distance condition enjoyed the excerpt more than those in the intermediate condition, who in turn enjoyed it more than those in the closeness condition. We expect a nonsignificant quadratic contrast but a significant linear contrast. Indeed, the quadratic contrast was not significant, t(67) = -0.65, n.s., and the linear contrast indicated that people primed with closeness (M = 3.99) liked the excerpt depicting embarrassment less than people primed with an intermediate amount of distance (M = 4.33), who in turn liked the excerpt less than people primed with distance (M = 5.35), t(67) = 2.41, prep = .93. The results support our hypothesis that the mere activation of physical-distance concepts (near vs. far), without explicit reference to the self or any social concepts, is sufficient to influence people’s evaluations.

Fig. 2.

Mean self-reported enjoyment of the book passage depicting embarrassment, in the closeness, intermediate, and distance conditions. Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

One alternative explanation for the pattern of results found in Study 1 is that the spatial prime influenced participants at the response level, without affecting their actual liking of the excerpt depicting embarrassment. Being primed with greater numerical magnitudes may have led participants to respond with larger numbers on the rating scales. Research on anchoring effects has demonstrated that simply asking people to consider objects with large magnitudes influences their subsequent responses on judgment tasks (Mussweiler & Strack, 2001; Oppenheimer, LeBoeuf, & Brewer, 2008; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Study 2 addressed this concern by examining the effects of spatial priming in a context in which the manipulation and dependent measures were expected to be inversely related.

STUDY 2

Method

Participants

Forty-two undergraduates (26 female, 16 male) were randomly assigned to the three spatial-prime conditions.

Materials and Procedure

The materials and procedure were identical to those used in Study 1, with two exceptions.

First, instead of reading an embarrassing story, participants read a violent excerpt taken from the book Survivor (Palahniuk, 1999). The excerpt featured a story of two brothers who had just survived a car accident. One of the brothers was horribly disfigured, and he begged to be beaten to death with a rock. We pilot-tested this passage with a separate set of 29 participants. On a single item tapping liking, from 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely), pilot-test participants rated this passage negatively (M = 3.21).

Second, instead of rating liking after reading the excerpt, participants rated their current positive and negative emotion using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (α = .72; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988).

No participants indicated any awareness of the purpose of the priming manipulation or the experimental hypothesis.

Results and Discussion

Do spatial cues influence the extent to which people find aversive media emotionally distressing? An ANOVA of the effect of spatial condition revealed that the three groups differed significantly in their reports of negative affect, F(2, 39) = 4.37, prep = .93, η2 = .18. We used the same linear and quadratic contrast weights used in Study 1. Again, the quadratic contrast was not significant, t(39) = -1.54, n.s.; the linear contrast showed that participants primed with closeness reported significantly more negative affect (M = 2.31) than participants primed with distance (M = 1.75), t(39) = -2.62, prep = .94. Participants’ reports of positive affect did not vary across conditions, all Fs < 1. This null finding may be due to the fact that some people feel positive following exposure to violent media, whereas others do not (Andrade & Cohen, in press). Alternatively, the null finding for positive affect may have been due to the fact that there is a steeper gradient for avoiding negative emotions than for approaching positive emotions, such that as one (figuratively) moves farther away from a stimulus, the negative effects of that stimulus will be muted to a greater degree than the positive aspects of that same stimulus (cf. Miller, 1961).

This finding provides further support for the hypothesis that spatial cues can affect people’s response to aversive media without their awareness. After exposure to violent media, people primed with a sense of spatial distance report less negative affect than people primed with a sense of spatial closeness. In the same way that people are less emotionally affected by an event if the event is 200 mi rather than 200 ft away (cf. Blanchard et al., 2004), so does distance priming mitigate the emotional impact of aversive media.

Overall, Studies 1 and 2 support the hypothesis that perceptual experiences with physical distances, without explicit reference to the self, affect people’s evaluations of and affective responses to emotionally evocative stimuli, and are consistent with emerging findings of embodied social cognition. In our view, priming spatial distance mutes the emotional aspects of events or stimuli because of the hard-wired association between distance and safety (e.g., Mobbs et al., 2007). To demonstrate this muting effect more directly, in Study 3 we tested the effect of perceptions of spatial distance and closeness on people’s estimations of the number of calories in unhealthy food.

STUDY 3

In this study, we again primed people with a sense of spatial closeness or spatial distance using a Cartesian plane. We then asked them to estimate the number of calories contained in healthy and unhealthy foods. This design allowed us to pit our account against CLT. In our view, because caloric content is an affect-laden, potentially dangerous feature of unhealthy food, we hypothesized that people primed with distance would estimate that unhealthy food contains fewer calories, compared with people primed with closeness. We did not expect distance priming to influence people’s estimations of the number of calories in healthy food, because for such foods, the (low) number of calories is an affectively mild feature. Thus, we expected an interactive effect of spatial-prime condition and food type on people’s judgments of caloric content. However, from a CLT perspective, calories are a low-level, peripheral feature of healthy and unhealthy food alike. Thus, if anything, CLT would predict only a main effect of spatial-prime condition.

Method

Participants

Fifty-nine adults from the New Haven community (31 female, 28 male) participated in a 3 (spatial prime: closeness vs. intermediate vs. distance) × 2 (food type: healthy vs. unhealthy) mixed design, with spatial-prime condition as the between-subjects factor and food type as the within-subjects factor.

Materials and Procedure

The priming procedure was identical to that used in Studies 1 and 2. Afterward, participants were given a list of 10 foods. Five of the foods were relatively healthy (yogurt, oatmeal, brown rice, apple, baked potato), and the remaining foods were relatively unhealthy (ice cream, french fries, potato chips, chocolate bar, cheeseburger). Participants were asked to estimate the number of calories in a single serving of each food. Ratings on this measure were internally consistent across the 10 food types (α = .75).

No participants indicated any awareness of the purpose of the priming manipulation or the experimental hypothesis.

Results and Discussion

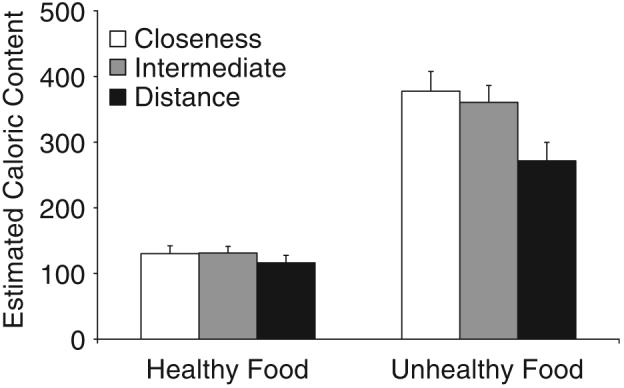

Does nonconscious activation of spatial-distance concepts influence people’s estimates of the calories in healthy versus unhealthy foods? We found an interaction between spatial-prime condition and food type in a repeated measures ANOVA, F(2, 56) = 3.36, prep = .89, η2 = .10 (see Fig. 3). Follow-up simple-effects analyses suggested that participants in the distance condition judged unhealthy food as containing fewer calories (M = 271.6) than did participants in the closeness condition (M = 391.3), F(2, 56) = 5.62, prep = .96. Notably, the mean calorie estimates of healthy foods did not differ across groups, F(2, 56) = 0.12, n.s. This interaction pattern suggests that priming spatial distance reduces sensitivity to the affect-laden features of unhealthy food and provides further evidence for the notion that distance reduces the affective intensity of stimuli.

Fig. 3.

Mean estimates of caloric content by food type and spatial-prime condition. Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

In Studies 1 through 3, we examined the effects of spatial closeness and distance on people’s responses to aversive media and unhealthy food, domains in which feelings of distance appear to play important roles in determining how people feel, and how they evaluate their experiences. In Study 4, we shifted our focus to evaluative targets that are a primary source of affect (both positive and negative) in one’s life. To stringently test our hypothesis that spatial cues can manipulate people’s judgments and feelings, we examined the effects of the spatial primes on the strength of people’s self-reported attachments to chronic, central, and important sources of affect and identity: their family and hometown.

STUDY 4

As in the previous studies, participants were primed with spatial closeness or spatial distance using a Cartesian plane. They then were asked to rate the strength of their bonds to their family members and to their hometown. We hypothesized that participants primed with distance would report weaker attachments to their family members and hometown, compared with participants primed with closeness.

Method

Participants

Eighty-four undergraduates (43 female, 41 male) were randomly assigned to the three spatial-prime conditions.

Materials and Procedure

The cover story and priming procedure were identical to those used in Studies 1 through 3. Following the prime, participants were given a questionnaire asking them to rate the strength of their bonds to their siblings, their parents, and their hometown, using a scale that ranged from 1 (not at all strong) to 7 (extremely strong). Responses to these three questions were averaged to provide an index of emotional attachment to one’s nuclear family and hometown (α = .50).

No participants indicated any awareness of the purpose of the priming manipulation or the experimental hypothesis.

Results and Discussion

Do representations of the concept of physical distance influence the extent to which people feel strong or weak bonds to their family or hometown? An ANOVA revealed that the three spatial-prime groups differed significantly in the reported strength of their bonds to their family and hometown, F(2, 81) = 4.97, prep = .95, η2 = .11. Again, using the contrast weights established in Study 1, we examined the difference between participants primed with closeness versus distance. The quadratic contrast was not significant, t(81) = 1.36, n.s.; the linear contrast showed that participants primed with distance reported weaker bonds to their family and hometown (M = 4.86), compared with participants primed with closeness (M = 5.61), t(81) = -2.86, prep = .96.

When people are primed with a sense of spatial distance, rather than closeness, they report weaker bonds to their siblings, parents, and hometown. These results suggest that cues to spatial distance increase feelings of emotional distance—that is, the emotional attachment people feel between themselves and other psychologically relevant entities. Thus, people’s judgments of the strength of their emotional attachments to important aspects of their social world are directly influenced by simple physical-distance cues. CLT is silent regarding these effects, as CLT does not predict whether people’s attachment to their family or hometown will be associated with high- or low-level construals. Along with Studies 1 and 3, Study 4 suggests that spatial distance, which can be manipulated without referring to the self, can meaningfully influence people’s affective judgments.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Plotting close or distant points on a Cartesian plane had a demonstrable impact on people’s evaluations and emotional self-reports. This suggests that perceptual and motor representations of spatial distance can influence people’s phenomenal experience, without explicit self-reference. Relative to priming people with spatial closeness, priming people with spatial distance muted the emotional impact of fiction, leading to more enjoyment of media depicting embarrassment and less emotional distress from media depicting violence. Priming spatial distance also influenced affective judgments, producing lower estimates of the caloric content of unhealthy food, but not healthy food. Perhaps most strikingly, priming distance through this unobtrusive method decreased the reported strength of emotional attachments people felt between themselves and their family and hometown. To our knowledge, the present studies are the first to demonstrate the effects of physical-distance cues on people’s judgments and emotional experiences.

Our goal was to extend current theory on spatial distance by demonstrating the pervasive manner in which spatial cues can affect people. Further investigations are needed to home in on the specific mechanism by which spatial priming influences people’s feelings and evaluations. At first blush, one may be tempted to look to CLT, according to which the effects of spatial manipulations on people’s judgments and feelings are mediated by changes in construal level: Greater distance is associated with abstraction and high-level construals, whereas reduced distance is associated with attention to concrete details and low-level construals (Trope & Liberman, 2003). However, some of the present data appear to be inconsistent with this view, as CLT does not account for the interaction pattern obtained in Study 3.

Given the developmental primacy of spatial concepts, and the deeply ingrained association between distance and safety in the human brain, we speculate that the representation of spatial distance between two arbitrary objects (in our case, two points on a Cartesian plane) automatically activates an abstract representation of the distance concept, which can alter responses to the world. People may nonconsciously use information about spatial closeness and spatial distance within the general environment to simulate psychological distances between themselves and other relevant variables (Barsalou, 1999; Niedenthal, Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber, & Ric, 2005). Future investigations should specify the mechanism by which these spatial-priming effects occur.

In conclusion, the basic concept of spatial distance has profound effects on the cognitive processes involved in appraisal and affect, effects that are beyond the purview of CLT. Feelings of distance can moderate the emotional intensity of stimuli, and can be activated by physical cues without reference to the self. These effects reveal the fundamental importance of distance cues in the physical environment for shaping people’s judgments and affective experiences, and highlight the ease with which aspects of the physical environment (and the spatial relations therein) can activate feelings of closeness or distance without one’s awareness.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to Williams and by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH60767) to Bargh. We thank Brad Bushman, Nira Liberman, Ezequiel Morsella, Eric Uhlmann, and four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft.

REFERENCES

- Andrade EB, Cohen JB. On the consumption of negative feelings. Journal of Consumer Research. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, Chartrand TL. The mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 253–285. [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW. Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:577–609. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Kuhn E, Rowell DL, Hickling EJ, Wittrock D, Rogers RL, et al. Studies of the vicarious traumatization of college students by the September 11th attacks: Effects of proximity, exposure and connectedness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:191–205. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroditsky L. Metaphoric structuring: Understanding time through spatial metaphors. Cognition. 2000;75:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Hogarth Press; London: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT. Perception as substitute trial and error. Psychological Review. 1956;63:330–342. doi: 10.1037/h0047553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT. Blind variation and selective retention in creative thought as in other knowledge structures. Psychological Review. 1960;67:380–400. doi: 10.1037/h0040373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HH. Space, time, semantics, and the child. In: Moore TE, editor. Cognitive development and the acquisition of language. Academic Press; New York: 1973. pp. 27–63. [Google Scholar]

- Darby P. The feng shui doctor: Ancient skills for modern living. Sterling; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier G, Turner M. The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. Basic Books; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Henderson MD, Eng J, Trope Y, Liberman N. Spatial distance and mental construal of social events. Psychological Science. 2006;17:278–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G, Johnson M. Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Cognition and motivation in emotion. American Psychologist. 1991;46:352–367. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie AM. The perception of causality in infants. Perception. 1982;11:173–186. doi: 10.1068/p110173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y, Stephan E. Psychological distance. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Vol. 2. Guilford; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K. Kant’s doctrine of the a priori in the light of contemporary biology. General Systems. 1962;7:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler JM. How to build a baby: II. Conceptual primitives. Psychological Review. 1992;99:587–604. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier BP, Robinson MD. Why the sunny side is up: Associations between affect and vertical position. Psychological Science. 2004;15:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NE. Some recent studies of conflict behavior and drugs. American Psychologist. 1961;16:12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D, Petrovic P, Marchant JL, Hassabis D, Weiskopf N, Seymour B, et al. When fear is near: Threat imminence elicits prefrontal-periaqueductal gray shifts in humans. Science. 2007;317:1079–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.1144298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussweiler T, Strack F. Considering the impossible: Explaining the effects of implausible anchors. Social Cognition. 2001;19:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Niedenthal PM, Barsalou LW, Winkielman P, Krauth-Gruber S, Ric F. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:184–211. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer DM, LeBoeuf RA, Brewer NT. Anchors aweigh: A demonstration of cross-modality anchoring and magnitude priming. Cognition. 2008;106:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palahniuk C. Survivor. W.W. Norton; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert TW. Your highness: Vertical positions as perceptual symbols of power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:1–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Trope Y. You focus on the forest when you’re in charge of the trees: Power priming and abstract information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:668–675. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman EC. Purposive behavior in animals and men. Century; New York: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y. Identification and inferential processes in dispositional attribution. Psychological Review. 1986;93:239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Temporal construal. Psychological Review. 2003;110:403–421. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. Good in bed. Pocket Books; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD. Strangers to ourselves: Discovering the adaptive unconscious. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]