Abstract

Infiltrating CD1a+ dendritic cells (DCs) have been associated with increased survival in a number of human cancers. This study investigated DC infiltration within breast cancers and the association with survival. Classical established prognostic factors, of tumour size, lymph node status, histological grade, lympho-vascular invasion, the KI-67 (MIB-1) fraction and the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) were also compared. A total of 48 breast cancer patients were followed from the time of surgery and CD1a density analysis for 5 years or until death. Our data set validated previous studies, which show a relationship between survival and the NPI (P<0.001), tumour size (P<0.01) and lymph node status (P<0.05). Although more patients were alive at the 5-year time point in the group with higher CD1a DC density than the lower CD1a DC group, this failed to reach statistical significance at the P=0.05 level. Analysis at 10 years postsurgery is required to investigate the association further.

Keywords: CD1a, dendritic cells, breast cancer, survival

Breast cancer is the most common terminal cancer in women in developed Western societies (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2002). The overall survival rate at 5 years is approximately 70%; however, prognostic factors can define subgroups within the larger group that may refine this figure to as high as 90% or to less than 20% in individual cases where certain prognostic factors are known (Pereira et al, 1995; Veronesi et al, 1995). The primary tumour pathology can predict the extent of local or distant tumour spread and augment clinical investigational information to better select appropriate surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy and to assist the understanding of likely clinical outcome. Lymph node involvement, tumour size and the histological grade of the tumour (Dalton et al, 1994; Page et al, 1998), in order of prognostic strength of association, are able to predict metastasis, recurrence and survival (Nixon et al, 1996). These have been integrated together to form the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) (Galea et al, 1992). The validity of the NPI has been shown repeatedly in breast cancer patients over 20 years such that patients with an NPI of <3.4 have been found to have an overall 15-year survival rate of 80%, those with an NPI of 3.4–5.4 have a moderate survival rate of 42%, while patients whose NPI is >5.4 have a 15-year survival rate of only 13%. Another feature that has been associated with clinical outcome is Ki-67 expression (expressed by all cells not in G0 phase), or the use of the MIB-1 antibody that reacts with part of the Ki-67 antigen (Pinder et al, 1995). Prognostic indices, such as the Nottingham Index, are important, useful tools that focus on tumour characteristics, but increasing interest is being directed towards the immunological responses that occur within the tumour microenvironment (Austyn, 1993; Coventry, 1999). Studies have shown that activated lymphocytes can cause tumour-specific cell lysis and that local immunosuppression appears to be present within the tumour microenvironment rendering the antitumour immune response ineffective (Whiteside et al, 1986a, 1986b; Vitolo et al, 1992, 1993; Coventry et al, 1996, 2002). A possible reason for the poor antitumour immune response may be the reduced number and activation status of dendritic cells (DCs) in human breast cancers. We have previously shown that DCs are absent, or only present in very low numbers, in most human breast cancers using CD1a and other markers and that DCs are poorly activated (Coventry et al, 1997; Hillenbrand et al, 1999; Coventry et al, 2002).

CD1a has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Coventry, 1999); however in brief, CD1a is a glycosylated type I transmembrane polypeptide chain noncovalently associated with β2 microglobulin (Shaw, 1998; Sieling, 1998). There is significant sequence homology between CD1a, and class I and II molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) (Shaw, 1998). The peptide binding site, while similar to MHC molecules, is longer, deeper and more hydrophobic (Zeng et al, 1997). CD1a has been used as a marker for DCs in a range of human tumours and the density of CD1a DC has been associated with clinical outcome. Dendritic Cell density, using a variety of markers including CD1a, has been reported to correlate with survival in a range of human tumour types including lung (Furukawa et al, 1985; Zeid and Muller, 1993), colon (Ambe et al, 1989), gastric (Tsujitani et al, 1987), nasopharyngeal (Gallo et al, 1991a; laryngeal (Gallo et al, 1991b)) and tongue carcinomas (Goldman et al, 1998).

A recent study demonstrated no apparent significant relationship between DC density and survival, using S-100 as a marker for DC, in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded breast cancer tissue samples (Lespagnard et al, 1999).

The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between CD1a DC density in fresh human breast cancer tissues, with disease-specific 5-year postsurgery survival. The possible association of CD1a density and other established prognostic markers was also investigated.

METHODS

Patient sample selection

Fresh tissue was taken from 51 female patients following surgical resection for infiltrating ductal breast carcinoma between 1990 and 1994 at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Three patients were excluded due to unavailability of 5-year follow-up data, giving a sample size of 48. Of these breast carcinomas, 42 tumours were infiltrating ductal in type and six were ductal carcinomas in situ (DCIS). Ethical approval was given for the studies by the RAH Human Ethics Committee.

Tissue processing

Tissue was embedded in OCT (Tissue Tek, Miles Scientific, Illinois) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Serial sections (4 μm) were cut using a cryostat (Leica, CM1500, Germany) onto gelatinised slides, acetone fixed (10 min) and air-dried.

Monoclonal antibodies and immunohistochemical techniques

Mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies (Mab), diluted with 10% normal horse serum (NHS, Sigma-Aldrich, Sydney) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), were varied in concentration to determine the optimum dilutions: CD1a at 1 : 1000 (Dako, Sydney), Cam 5.2 at 1 : 500 (Becton Dickinson, Sydney, Australia), murine isotype controls IgG1, IgG2a (supernatants at 1 : 16, L Ashman, IMVS Adelaide, Australia), second antibody biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse IgG/IgM at 1 : 500 (Dako, Sydney) and streptavidin–HRP at 1 : 1000 (Pierce, USA).

All reactions were carried out with PBS washes in triplicate between incubations at room temperature. Sections were blocked with 10% NHS (30 min), incubated overnight in a humidified chamber with primary antibody, followed by biotinylated second antibody incubation (1 h). Endogenous peroxidase blockade (0.5% hydrogen peroxide; methanol, 20 min) was followed by streptavidin–HRP incubation (1 h). High-sensitivity nickel chloride-enhanced diaminobenzidene (nickel DAB) techniques were used and sections were counterstained with methyl green (Coventry et al, 1994; 1995; Hillenbrand et al, 1999).

Visual quantitation

Cell density was quantified as the mean of 50 random high power fields (hpf) per frozen section (field size 0.375 mm diameter, 0.11 mm2, × 400 magnification) using relevant stains for respective cell types to enable a comparison of the density and distribution of different cell types (Dunnill, 1968).

Identification of DC

Anti-CD1a Mab was used to identify DC in tissue sections. Assessment of DC morphology was also performed and assisted identification.

Identification of tumour cells

The anti-cytokeratin Mab, Cam 5.2, was used to identify tumour (and normal) epithelial cells in the adenocarcinomas, to exclude the possibility of CD1a staining of epithelial cells as opposed to DC (Makin et al, 1984; Hillenbrand et al, 1999).

Follow-up data collection

The 5-year follow-up data were obtained from hospital case notes and clinical records, general practitioners, surgeons and the government registry of Deaths. This included interstate follow-up. The patient details included age at diagnosis/surgery, date of diagnosis/surgery, duration of follow-up, date of death, cause of death, date of metastasis/local recurrence and the therapy received.

Pathology data collection

The original pathology reports were obtained for all 48 patients. These were used to determine the tumour microscopic size, grade, lymph node status, presence of lympho-vascular invasion and the Ki-67 (or MIB-1) fraction. The NPI was calculated using this data. The tumour grade was assessed according to the Scarfe, Bloom and Richardson system identifying grade I, II or III for each invasive tumour (Bloom and Richardson, 1957; Scarff and Tolono, 1968). Ductal carcinoma in situ was also noted separately to any invasive component, and specifically tabulated if this was the only tumour present.

Causes of death

For the patients who died, the cause of death was established through the South Australian Department of Births, Deaths and Marriages. Breast cancer-specific mortality was used for the mortality calculations.

Statistics

All statistics were performed with the assistance of statisticians (see Acknowledgments) using the SAS© program. The primary outcome measure was breast cancer-specific survival at 5 years from the time of diagnosis. Statistical correlations and associations between survival and the prognostic factors (CD1a density, tumour size, lymph node status, histological grade, the NPI and the Ki-67 (or MIB-1) fraction) were performed. A correlation between CD1a density and the NPI was investigated using Fisher's Exact χ2 test due to the small sample size used in the study. The prognostic indicators were treated as categorical, instead of continuous variables, due also to the small sample size. Indices were used in standard methodological groupings: the NPI, as recommended by Galea et al (1992); lymph node metastases into present or absent; and histological grade was classified as Bloom and Richardson grades I, II and III or separately as DCIS. CD1a density, tumour size and Ki-67 fraction were divided into two groups, either side of the respective medians. The groups were therefore defined around the medians of: (i) CD1a density 0.78 (cells/hpf), (ii) tumour size 25 (mm) or (iii) Ki-67 fraction 45 (%), respectively. Medians were chosen on statistical grounds to limit influence from any non-normal distribution of data. For CD1a density, several cutoff levels lower and higher than the median were also chosen for extended analysis.

RESULTS

The data obtained are shown in Table 1 . The median age was 60.5 years at diagnosis with a range from 26 to 84 years. Survival data were obtained for 48 patients with CD1a density (and other) measurements. Of these, 12 women had died before the 5-year time point from surgery/diagnosis. All of these deaths were attributable to breast cancer.

Table 1. Patient data for the study group.

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| n=48 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 60.5 | 26–84 |

| Age (survivors at 5 years) | 67 | 31–89 |

| Age (died before 5 years) | 60.5 | 41–87 |

| CD1a count (cells/hpf) | 0.78 | 0–14.85 |

| Tumour size (mm) | 25 | 8–200 |

| Nodes removed total | 12 | 1–24 |

| NPI | 3.55 | 1.02–7 |

| Number in category | ||

| Tumour grade | ||

| DCIS | 6 | |

| I | 8 | |

| II | 24 | |

| III | 10 | |

| DCIS component present | 38 | |

| Positive nodes | 14 | |

| Vascular invasion | 12 | |

| Tamoxifen | 21 | |

| Radiotherapy | 22 | |

| Chemotherapy | 15 | |

| Family history | 7 | |

| Metastases at diagnosis | 2 | |

| Metastases at 5 years | 10 | |

| Ki-67 (+ve >20%) | 15 | |

| ER (+ve >50%) | 24 | |

| PR (+ve >50%) | 20 |

Traditional tumour-associated prognostic factors and survival

Tumour size <25 mm diameter was demonstrated to be a prognostic index for survival (P<0.02). The absence of lymph node metastasis was also found to be associated with survival (P<0.05). Limited data on nine pathology reports prevented calculation of the NPI, leaving 39 patients where the NPI was available. Values ranged from 1.02–7, with 13 women in the good prognostic group, 20 in the moderate group and six women in the poor prognostic group. The NPI was strongly associated with survival (P<0.001), with 100% of women dying in the poor prognostic group.

The distribution of tumours according to grade was: six DCIS; eight grade I; 24 grade II and 10 grade III. The histological grade of the tumour was not significantly associated with survival with a P-value of 0.08. The Ki-67 (MIB-1) fraction was also not found to be associated with survival (P=0.091) in this series. The presence of lympho-vascular invasion within the tumour was associated with mortality (P=0.0126). As expected, the presence of systemic metastases was associated with reduced survival (P<0.01). However, in contrast, the presence of local–regional tumour recurrence was not associated with increased risk of death (P=0.304).

CD1a DC density and survival

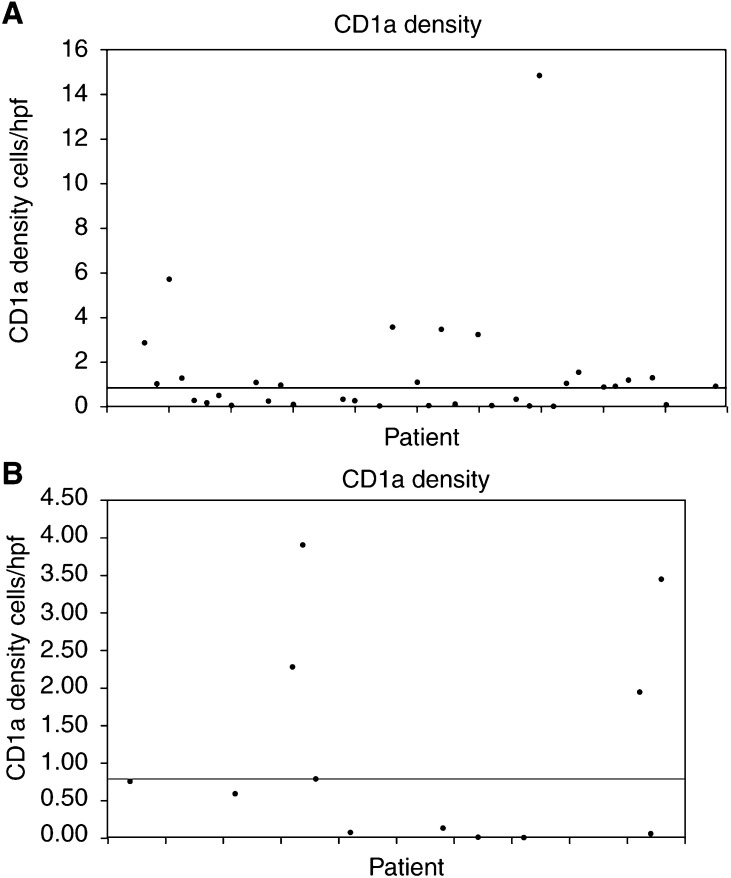

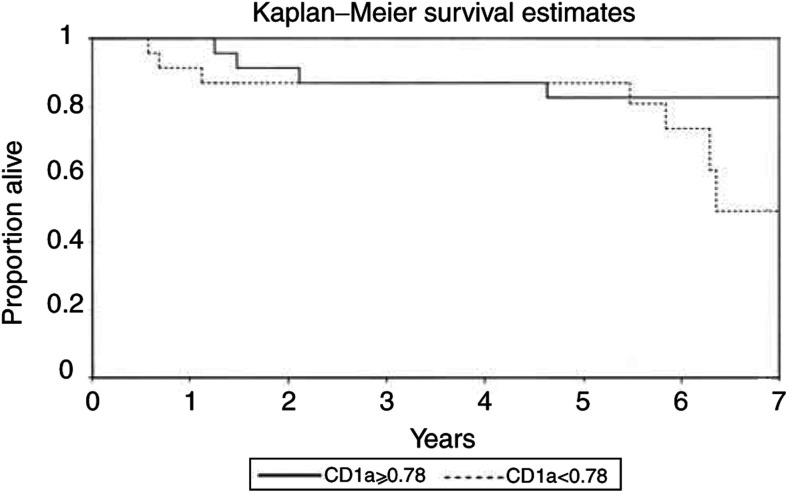

CD1a staining was confined to DC with no staining of Cam 5.2-positive epithelial cells in serial sections. The CD1a count was available for all 48 patients ranging from 0 to 14.85, with a median of 0.78 cells per high power field. In 40 out of 48 breast cancers, CD1a-positive cells were detectable using these methods. Comparison of raw data is shown by the dispersion of CD1a density data around the median for patients alive (Figure 1A) and dead (Figure 1B) at 5 years postsurgery. A higher death rate (32%) was observed in the patients with a lower CD1a count, compared to 18% mortality for the group with a higher CD1a density within their breast tumours. However, the CD1a count was not significantly associated with 5-year survival (P=0.331) (Table 2 ). The data were also analysed using the Kaplan–Meier method relating the survival curves of patients with CD1a densities either less than the median of 0.78 cells/hpf or 0.78 and greater (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Scattergram showing the dispersion of CD1a density data around the median (A) for patients alive at 5 years postsurgery and (B) for patients dead at 5 years postsurgery.

Table 2. CD1a density and survival.

| (n=47) | Dead (%) | Alive (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low CD1a | 32 | 68 |

| High CD1a | 18 | 82 |

Note that 32% of the patients with low CD1a density died within 5 years, while only 18% of those with a count died (n=47). The association between the number of CD1a+ DCs was not significantly associated with survival at 5 years postsurgery (P=0.331).

Figure 2.

Survival curves of patients with CD1a densities either less than the median of 0.78 cells/hpf or 0.78 and greater using the Kaplan–Meier method.

The association between CD1a count and the NPI was also not significant (P=0.486), but again the raw data showed an apparent trend towards a higher, or a worsening, NPI and lower CD1a density. The sample (n=39) for this statistic was necessarily small due to a lack of complete data for the calculation of the NPI (Table 3 ).

Table 3. Cd1a density and NPI.

| (n=39) | Low CD1a (%) | High CD1a (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NPI>5.4 (poor prognosis) | 80 | 20 |

| NPI 3.4–5.4 (moderate prognosis) | 50 | 50 |

| NPI<3.4 (good prognosis) | 46 | 54 |

The association between CD1a and the NPI shows a nonsignificant (P=0.486) trend. Note that 20% of the patients with a higher CD1a density had a high (unfavourable) NPI, while 80% of the patients with a low CD1a density had an unfavourable NPI. The trend was reversed for a low (more favourable) NPI.

Analyses were performed between CD1a and tumour size, grade, nodal status, Ki-67 (MIB-1), presence/absence of metastases, presence/absence of recurrence, presence/absence of lympho-vascular invasion. No statistical association at the P=0.05 level could be found between CD1a density and any of these prognostic variables.

DISCUSSION

Dendritic cell density in human tumour tissues has been investigated using a variety of markers and methods. Principally, CD1a and S-100 have been used for tissue section investigations, but more recently, CD83, CD86, CMRF-44/-56 and other markers have been utilised. CD1a molecules have been reviewed elsewhere (Coventry, 1999), but appear to have a role in antigen presentation showing relatively tightly restricted expression on DC. A very small subgroup of monocytes in adults and thymocytes in early life can also express CD1a. CD1a-positive DCs have been reported to be present within breast cancers from very early, preinvasive DCIS lesions to invasive ductal carcinomas, but there was no statistical correlation between DC density and the grade of the tumour (Hillenbrand, 1999). On the other hand, S-100-positive DC do appear to show some correlation with the breast tumour grade (Bell et al, 1999; Lespagnard et al, 1999), indicating that CD1a and S-100 define somewhat different populations of DCs in breast cancers. S-100 is a small acidic regulatory protein involved in a wide range of cellular processes and exhibits relative tissue specificity for DCs and cells of neural origin, including melanoma cells (Heizmann et al, 2002). The density of DCs, using either CD1a or S-100 as markers for DC, has been reported for a variety of human cancers including cervix (Younes et al, 1968; Bethwaite et al, 1996), ovary (Eisenthal et al, 2001), lung (Bassett et al, 1974; Fox et al, 1989; Zeid and Muller, 1993), larynx (Schenk, 1980), salivary glands (David and Buchner, 1980), skin (Gatter et al, 1980), breast (Hillenbrand et al, 1999; Coventry et al, 2002), thymus (Hammar et al, 1986), oesophagus (Matsuda et al, 1990), stomach (Tsujitani et al, 1987), pancreas (Dallal et al, 2002), thyroid (Schroder et al, 1988; Willgeroth et al, 1992), colon (Ambe et al, 1989), nasopharynx (Nomori et al, 1986; Gallo et al, 1991a; laryngeal (Gallo et al, 1991b)), oral (Kikuchi et al, 2002), prostate, bladder and kidney (Bigotti et al, 1991; Inoue et al, 1993; Troy et al, 1998a, 1998b, 1999). Furthermore, DC numbers, as measured using either CD1a or S-100 antibodies, have been positively associated with improved outcome (increased survival) for many of these cancers, although the mechanism remains unclear. S-100-positive DC number has been associated with improved survival for colon, gastric, lung and laryngeal carcinomas (Tsujitani et al, 1987; Ambe et al, 1989; Gallo et al, 1991a, 1991b; Zeid and Muller, 1993). More recently, breast cancer was investigated, but no association of S-100 with survival could be shown (Lespagnard et al, 1999).

The data regarding CD1a and survival are more limited. The density of CD1a-positive DC has been directly related to survival for tongue carcinomas (Goldman et al, 1998) and reduced tumour recurrence in ovarian carcinoma (Eisenthal et al, 2001). Until recently, no study has specifically addressed the relationship of CD1a density in breast cancer to clinical outcome or survival.

Our findings in this study addressed this issue and showed that the density of tumour infiltrating CD1a+ dendritic cells did not significantly correlate (at the P=0.05 level) with overall survival at the 5-year time point following surgery. Clearly, sample size may have been a possible limitation of our study, since a trend was demonstrated (shown in Table 2). However, the sample size was sufficiently large to demonstrate a statistical correlation between the classical prognostic variables of tumour size, lymph node status, lympho-vascular invasion, metastases and the NPI. Our data lend further support to the findings of Lespagnard et al (1999) from a similar study using S-100 as an alternative marker for DC in formalin-fixed archival breast cancer tissues. Notably, their study examined 143 cases and also showed no statistical difference between DC numbers as measured by S-100 expression and 5-year survival. A very recently published study by Iwamoto et al (2003) showed similar findings, indicating that CD1a density in breast cancer was not related to clinical outcome or survival. Taken collectively, these findings imply that the density of DC per se, as measured by CD1a or S-100, does not appear to act as an independent determinant of overall 5-year survival from breast carcinoma.

These are important findings and indicate that either (i) DC density may not directly determine tumour cell growth, metastasis and outcome in breast cancer or (ii) CD1a and S-100 as conventional measures of DC density may not be sensitive or specific enough for prognostic use.

There is considerable evidence that tumour-specific responses are present in human breast cancers, but that the immune response is inhibited and/or ineffective in most cases. The demonstration of tumour-specific lysis by tumour infiltrating lymphocytes strongly indicates that DCs are important in in vivo breast cancer antitumour immunity (Baxevanis et al, 1994). The concept of a detectable antitumour response in breast cancer is further supported by other demonstrations of tumour-specific cytolytic and cytokine responses to breast cancer cells utilising different methods (Whiteside et al, 1986a, 1986b; Shwartzentruber et al, 1992). These findings show that the antitumour immune response in breast cancer is ineffective and that deficient DC function, at least in part, may be responsible for this (Coventry et al, 1996; Gabrilovich et al, 1997). The maturity and location of DC within breast tumours may not be uniform, such that more mature DCs, expressing differentiation/activation markers such as CD83, have been noted to be located peritumourally around the tumour mass, rather than infiltrating within it (Bell et al, 1999; Tsuge et al, 2000). Further recent data from two collaborative laboratories, using different methods and samples, demonstrated that the activation of DC was very low or absent within the breast cancer microenvironment using a variety of markers (Coventry et al, 2002). The finding that activation was low or absent in tumour-associated DC populations in most breast cancers may have some bearing on the lack of apparent statistical association between CD1a and S-100 expression and survival. The observations that activated, mature DCs were restricted to a peritumoural location rather than within the tumour (Bell et al, 1999; Tsuge et al, 2000) imply that regional differences around and within breast cancers may be important in determining the capacity of DC to present antigens depending on their location. CD1a+ DC may not have the capacity to adequately mature, and present antigen within the tumour microenvironment, or may become inhibited. Markers of DC differentiation/activation, such as CD83 and other molecules, may therefore be more accurate in establishing the true capacity for antigen presentation within the tumour microenvironment. Clinical evidence for this theory is provided by recent work that shows that CD83 expression correlates directly with clinical outcome (Iwamoto et al, 2003). The presence of a nonstatistically significant trend in the data from analysis of both (i) CD1a density and survival; and also (ii) CD1a density and NPI suggests that CD1a+ DC density may be important, but this is currently unclear. However, an association between CD1a expression may reach statistical significance at the 10-year time point from diagnosis, and clearly later analysis is needed to investigate this aspect. Further studies are necessary to delineate the role of DC in relation to survival in human breast cancer, and the mechanisms for enhancing in vivo DC function. Immunotherapeutic methods for attracting DC into, and activating DC within, the tumour microenvironment are required to improve the antitumour immune response. The long dormant periods that are clinically observed between initial diagnosis/surgery and subsequent recurrence in the clinical setting strongly indicate that local mechanisms are operational within the tumour microenvironment and are capable of successfully limiting tumour growth. Understanding DC function and activation may explain the mechanism for this phenomenon and reveal new clinically useful therapeutic tools.

Acknowledgments

We thank our statisticians Nicole Chamberlain and Heather McElroy, from the Department of General Practice, for their expert advice and analyses. Surgeons Drs Gill, Carter and Malycha are gratefully acknowledged for provision of some specimens, and pathologists at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Sciences for antibodies and advice. We also thank Evy Hillenbrand and Angela Neville (PhD students) for technical assistance with immunohistochemical staining during some of their studies. The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons Research Foundation (Florance Cancer Research Fellowship awarded to BJC) and the Anti-Cancer Foundation of the Universities of South Australia provided some of the funds, together with University of Adelaide Rural Surgical Service funds. We are grateful for gifts of antibodies from Dr L Ashman (Adelaide) (Melbourne), Professor H Zola (Adelaide), Professor A McMichael (Oxford). Thanks are also due to Dr Su Heinzel for critically reviewing the manuscript.

References

- Ambe K, Mori M, Enjoji M (1989) S-100 protein-positive dendritic cells in colorectal adenocarcinomas: distribution and relation to clinical progress. Cancer 63: 496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2002) Causes of Death Australia. Canberra: ABS (www.abs.gov.au) [Google Scholar]

- Austyn JA (1993) The dendritic cell system and anti-tumour immunity. In vivo 7: 193–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basset F, Soler P, Whyllie L (1974) Langerhans cells in bronchoalveolar tumour of the lung. Vich Arch (Pathol Anat) 362: 315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxevanis CN, Dedoussis GVZ, Papadopoulos NG, Missitzis I, Stathopoulos GP, Papamichail M (1994) Tumour specific cytolysis by tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. Cancer 74 (4): 1275–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D, Chomarat P, Broyles D, Netto G, Harb GM, Lebecque S, Valladeau J, Davoust J, Palucka KA, Banchereau J (1999) In breast carcinoma tissue, immature dendritic cells reside within the tumor, whereas mature dendritic cells are located in peritumoral areas. J Exp Med 190 (10): 1417–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethwaite PB, Holloway LJ, Thornton A, Delahunt B (1996) Infiltration by immunocompetent cells in early stage invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a prognostic study. Pathology 28 (4): 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigotti G, Coli A, Castagnola D (1991) Distribution of Langerhans cells and HLA class II molecules in prostatic carcinomas of different histological grade. Prostate 19: 73–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom HJG, Richardson WW (1957) Histological grading and prognosis in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 11: 359–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry BJ (1999) Review of CD1a putative dendritic cells in human breast cancers. AntiCancer Res 19: 3183–3188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry BJ, Austyn JM, Chryssidis S, Hankins D, Harris A (1997) Identification and isolation of CD1a positive putative tumour infiltrating dendritic cells in human breast cancer. In Dendritic cells in Fundamental and Clinical Immunology, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P (ed) Vol 3. NY: Plenum Press, Adv Exptl Med Biol 417: 571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry BJ, Bradley J, Skinner JM (1995) Differences between standard and high-sensitivity immunoperoxidase staining methods in tissue sections–comparison of immunoperoxidase staining methods using computerised video image analysis. Pathology 27: 221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry BJ, Lee PL, Gibbs D, Hart DN (2002) Dendritic cell density and activation status in human breast cancer–CD1a, CMRF-44, CMRF-56 and CD-83 expression. Br J Cancer 86: 546–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry BJ, Neoh S, Mantzioris B, Skinner JM, Bradley J, Zola H (1994) Comparison of the sensitivity of immunoperoxidase staining methods with high-sensitivity fluorescence flow cytometry–antibody quantitation on the cell surface. J Histochem Cytochem 42: 1143–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry BJ, Weeks S, Heckford S, Sykes P, Skinner J, Bradley J (1996) Lack of interleukin-2 (IL-2) cytokine expression despite IL-2mRNA transcription in tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in primary human breast carcinoma: selective expression of early activation markers. J Immunol 156: 3486–3492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallal RM, Christakos P, Lee K, Egawa S, Son YI, Lotze MT (2002) Paucity of dendritic cells in pancreatic cancer. Surgery 131 (2): 135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton LW, Page DL, Dupont WD (1994) Histologic grading of breast cancer: a reproducibility study. Cancer 73: 2765–2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David R, Buchner A (1980) Langerhans cells in pleomorphic adenoma of sub-mandibular salivary gland. J Pathol 131: 127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnill MS (1968) Quantitative methods in histology. In Recent Advances in Clinical Pathology, Dyke SC (ed.) London: Churchill Livingstone [Google Scholar]

- Eisenthal A, Polyvkin N, Bramante-Schreiber L, Misonznik F, Hassner A, Lifschitz-Mercer B (2001) Expression of dendritic cells in ovarian tumors correlates with clinical outcome in patients with ovarian cancer. Hum Pathol 32 (8): 803–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston CW, Ellis IO (1991) Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology 19: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SB, Jones M, Dunnill MS, Gatter KC, Mason DY (1989) Langerhans cells in human lung tumour: an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 14: 269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Watanabe S, Kodama T, Sato Y, Sihimosato Y, Suemasa K (1985) T-zone histiocytes in adenocarcinoma of the lung in relation to postoperative prognosis. Cancer 56: 2651–2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich DI, Corak J, Ciernik IF, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP (1997) Decreased antigen presentation by dendritic cells in patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 3 (3): 483–490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea MH, Blarney RW, Elston CW, Ellis IO (1992) The Nottingham Progno-stic Index in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 22: 207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo O, Bianchi S, Giannini A, Gallina E, Libonati GA, Fini-Storchi O (1991a) Correlation between histopathological and biological findings in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its prognostic significance. Laryngoscope 101: 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo O, Libonati GA, Gallina E, Fini-Storchi O, Giannini A, Urso C, Bondi R (1991b) Langerhans cells related to prognosis in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117 (9): 1007–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatter KC, Morris HB, Roach B (1980) Langerhans cells and T cells in human skin tumours. Immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 8: 229–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman SA, Baker E, Weyant RJ, Clark MR, Myers JN, Lotze MT (1998) Peritumoral CD1a-positive dendritic cells are associated with improved survival in patients with tongue carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124: 641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar S, Bockus D, Remington F (1986) The widespread distribution of Langerhans cells in pathological tissue. An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Human Pathol 17: 894–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizmann CW, Fritz G, Schafer BW (2002) S100 proteins: structure, functions and pathology. Front Biosci 7: d1356–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand EE, Neville AM, Coventry BJ (1999) Immunohistochemical localisation of CD1a-positive putative dendritic cells in human breast tumours. Br J Cancer 79: 940–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Furihata M, Ohtsuki Y, Fujita Y (1993) Distribution of S-100 protein-positive dendritic cells and expression of HLA-DR antigen in transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in relation to tumour progression and prognosis. Virch Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 422 (5): 351–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto M, Shinohara H, Miyamoto A, Okuzawa M, Mabuchi H, Nohara T, Gon G, Toyoda M, Tanigawa N (2003) Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells expressing CD83 in human breast carcinomas. Int J Cancer 104 (1): 92–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Kusama K, Taguchi K, Ishikawa F, Okamoto M, Shimada J, Sakashita H, Yamamo Y (2002) Dendritic cells in human squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Anticancer Res 22 (2A): 545–557 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lespagnard L, Gancberg D, Rouas G, Leclercq G, de Saint-Aubain Somerhausen N, Di Leo A, Piccart M, Verhest A, Larsimont D (1999) Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells in adenocarcinomas of the breast: a study of 143 neoplasms with a correlation to usual prognostic factors and to clinical outcome. Int J Cancer 84 (3): 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makin CA, Bobrow LG, Bodmer WF (1984) Monoclonal antibody to cytokeratin for use in routine histopathology. J Clin Pathol 37 (9): 975–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Mori M, Tsujitani S, Ohno S, Kuwano H, Sugimachi K (1990) Immunohistochemical evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma antigen and S-100 protein-positive cells in human malignant esophageal tissues. Cancer 65 (10): 2261–2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon AJ, Schnitt SJ, Gelman R, Gage I, Bornstein B, Hetelekidis S, Recht A, Silver B, Harris JR, Connolly JL (1996) Relationship of tumour grade to other pathologic features and to treatment outcome of patients with early stage breast carcinoma treated with breast-conserving therapy. Cancer 78: 1426–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomori H, Watanabe S, Nakajima T, Shimosato Y, Kameya T (1986) Histiocytes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in relation to prognosis. Cancer 57: 100–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page DL, Jensen RA, Simpson JF (1998) Routinely available indicators of prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 51: 195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira H, Pinder SE, Sibbering DM, Galea MH, Elston CW, Blamey RW, Robertson JFR, Ellis IO (1995) Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. IV: Should you be a typer or a grader? A comparative study of the two histological prognostic features in operable breast carcinoma. Histopathology 27: 219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder SE, Wencyk P, Sibbering DM, Bell JA, Alston CW, Robertson JF, Nicholson R, Balmey RW, Ellis IO (1995) Assessment of the new proliferation marker MIB 1 in breast carcinoma using image analysis: associations with other prognostic factors and survival. Br J Cancer 71: 146–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarff RW, Tolono H (1968) Histological Typing of Breast Tumours (International Histological Classification of Tumours: No 2). Geneva: World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- Schenk P (1980) Langerhans cells in invasive laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg) 59: 232–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder S, Schwarz W, Rehpenning W, Loning T, Bocker W (1988) Dendritic/Langerhans cells in and prognosis in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: immunohistochemical study of 106 thyroid neoplasms correlated to follow-up data. Am J Clin Pathol 89: 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzentruber DJ, Solomon D, Rosenberg SA, Topalian SL (1992) Characterization of lymphocytes infiltrating human breast cancer: specific immune reactivity detected by measuring cytokine secretion. J Immunother 12 (1): 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw S (1998) CD Guide. Sixth International Leukocyte Typing Workshop, Kobe, Japan. In Leukocyte Typing VI. Kishimoto T, Kikutani H, von dem Borne AEG, Goyert SM, Mason D, Miyasaka M, Moretta L, Okumura K, Shaw S, Springer TA, Sugamura K, Zola H (eds). pp 1109–1110. New York: Garland press Ltd [Google Scholar]

- Sieling PA (1998) A broader role for CD1 in the spectrum of immune responses. Immunologist 6 (3): 112–116 [Google Scholar]

- Troy A, Davidson P, Atkinson C, Hart D (1998b) Phenotypic characterisation of the dendritic cell infiltrate in prostate cancer. J Urol 160 (1): 214–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AJ, Davidson PJ, Atkinson CH, Hart DN (1999) CD1a dendritic cells predominate in transitional cell carcinoma of bladder and kidney but are minimally activated. J Urol 161 (6): 1962–1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AJ, Summers KL, Davidson PJ, Atkinson CH, Hart DN (1998a) Minimal recruitment and activation of dendritic cells within renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 4 (3): 585–593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge T, Yamakawa M, Tsukamoto M (2000) Infiltrating dendritic/Langerhans cells in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 59 (2): 141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujitani S, Furukawa T, Tamada R, Okamura T, Yasumoto K, Sugimachi K (1987) Langerhans cells and prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer 59: 501–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi S, Marubini E, Del Vecchio M, Manzari A, Andreola S, Greco M, Luini A, Merson M, Saccozzi R, Rilke F, Salvadori B (1995) Local recurrences and distant metastases after conservative breast cancer treatments: partly independent events. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitolo D, Kanbour A, Johnson JT, Herberman RB, Whiteside TL (1993) In situ hybridisation for cytokine gene transcripts in the solid tumour microenvironment. Eur J Cancer 29A (3): 371–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitolo D, Zerbe T, Kanbour A, Dahl C, Herberman RB, Whiteside TL (1992) Expression of mRNA for cytokines in tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells in ovarian adenocarcinoma and invasive breast cancer. Int J Cancer 51 (4): 573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside TL, Miescher S, Hurlimann J, Moretta L, von Fliedner V (1986a) Clonal analysis and in situ characterization of lymphocytes infiltrating human breast carcinomas. Cancer Immunol Immunother 23 (3): 169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside TL, Miescher S, MacDonald HR, Von Fliedner V (1986b) Separation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from tumor cells in human solidtumors. A comparison between velocity sedimentation and discontinuous density gradients. J Immunol Methods 90 (2): 221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willgeroth C, Floegel R, Rosier B (1992) The importance of S-100 protein positive Langerhans cells and Leu-M1 positive tumor cells for prognosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Zentralbl Chir 117 (11): 603–606 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes MS, Robertson EM, Bensome SA (1968) Electron microscope observation on Langerhans cells in the cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol 102 (3): 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeid NA, Muller HK (1993) S-100 positive dendritic cells in human lung tumours associated with cell differentiation and enhanced survival. Pathology 25: 338–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Castano AR, Segelke BW, Stura EA, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. (1997) Crystal structure of mouse CD1: an MHC-like fold with a large hydrophobic binding groove. Science 277 (5324): 339–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]