Abstract

During postnatal development of the central nervous system (CNS), the response of GABAA receptors to its agonist undergoes maturation from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing. This switch in polarity is due to the developmental decrease of the intracellular Cl− concentration in neurons. Here we show that absence of NKCC1 in P9-13 CA3 pyramidal neurons, through genetic manipulation or through bumetanide inhibition, results in a significant increase in cell excitability. Furthermore, the pro-convulsant agent 4-aminopyridine induces seizure-like events in NKCC1-null mice but not in wild-type mice. Measurements of muscimol responses in the presence and absence of NKCC1 shows that the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter only marginally affects intracellular Cl− in P9-P13 CA3 principal neurons. However, large increases in intracellular Cl− are observed in CA3 pyramidal neurons following increased hyperexcitability, indicating that P9-13 CA3 pyramidal neurons lack robust mechanisms to regulate intracellular Cl− during high synaptic activity. This increase in the Cl− concentration is network-driven and activity-dependent, as it is blocked by the non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist DNQX. We also show that expression of the outward K-Cl cotransporter, KCC2, prevents the development of hyperexcitability, as a reduction of KCC2 expression by half results in increased susceptibility to seizure under control and 4-AP conditions.

Keywords: Na-K-2Cl cotransport, K-Cl cotransport, hippocampus, seizure, 4-aminopyridine, gamma aminobutyric acid

1. INTRODUCTION

The hippocampus is an important CNS structure involved in temporal lobe epilepsy (Aronica, et al., 2007, Liu, et al., 2007). Inhibition provided by ionotropic GABAA receptors is essential in maintaining normal brain function and protecting against seizures. Indeed, the GABAergic tone, by hyperpolarizing postsynaptic membranes and increasing membrane conductances (shunting), dampens excessive glutamatergic excitation and prevents synchronization of neuronal networks into epileptiform activity. GABAA receptors mediate the hyperpolarization effect through the opening of an anion channel, allowing Cl− to move into the cell (and HCO3− to move out under physiological conditions with much less permeability), and leading to plasma membrane hyperpolarization. The inward driving force for Cl− ions is due to the low intracellular Cl− concentration which is maintained by a secondary active transport mechanism, the neuronal-specific K-Cl cotransporter, KCC2. This overall process matures concomitant with the development of glutamatergic excitation (Ben-Ari, 2007, Ben-Ari, et al., 2007, Represa and Ben-Ari, 2005, Stein, et al., 2004), which in rodents translates to the first two weeks of postnatal life. At birth, however, neuronal Cl− is elevated and the equilibrium potential of Cl− (ECl) is above the resting membrane potential (LoTurco, et al., 1995, Luhmann and Prince, 1991, Owens, et al., 1996). This implies that the absence of KCC2 expression at birth, alone, cannot account for the high neuronal Cl−.

The formation of neuronal connections during early brain development also depends on the delicate balance between inhibition and excitation (Ben-Ari, 2002). As the rodent brain switches from GABA excitation to GABA inhibition during the first two weeks of postnatal life, this period constitutes a critical moment as excessive GABAergic excitation might lead to increased seizure susceptibility (Dzhala and Staley, 2003, Khazipov, et al., 2004)) while excessive GABAergic inhibition might prevent growth or synapse formation (Ben-Ari, 2002). Based on the observation that NKCC1 expression is high in immature CNS neurons and down-regulated during postnatal development (Dzhala, et al., 2005, Plotkin, et al., 1997, Wang, et al., 2002), several studies have examined the possibility that Cl− accumulation in immature neurons is mediated by the inward Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (Achilles, et al., 2007, Chub, et al., 2006, Fukuda, et al., 1998, Ikeda, et al., 2003, Rohrbough and Spitzer, 1996, Sipila, et al., 2006, Yamada, et al., 2004). By using bumetanide to inhibit the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, these studies show a role for NKCC1 in accumulation of intracellular Cl−. Furthermore, a report indicates that NKCC1 may facilitate seizures in the developing brain (Dzhala, et al., 2005) by accumulating intracellular Cl− in the hippocampal pyramidal neurons and thus attenuating the GABAA receptor mediated inhibition. However, high external [K+] was used in this study to increase brain hyperexcitability, which is a concern when studying the role of cation-chloride cotransporters, since they are K+-dependent transport pathways, and elevated external K+ increases inward Cl− transport. Interestingly, in a recent study where 1μM Kainate was used as a model, inhibition of NKCC1 by bumetanide was shown to have opposite effect on seizure activities (Kilb, et al., 2007). Thus, whether NKCC1 increases excitability by raising Cl− in hippocampal pyramidal cells is still unresolved. In fact, several other studies have questioned the role of the cotransporter in Cl− accumulation in developing neurons of the brainstem (Balakrishnan, et al., 2003) and retina (Zhang, et al., 2007). Furthermore, there is evidence that NKCC1 may not be ubiquitously down-regulated in the developing hippocampus, but instead undergoes a change of localization from the soma of interneurons and pyramidal neurons to dendritic compartments (Marty, et al., 2002), or from neuronal layers to glial formations (Hubner, et al., 2001). These observations are significant since NKCC1-mediated elevation of Cl− in GABAergic interneurons may reduce their inhibition by GABA, resulting in increased inhibitory output to pyramidal neurons and higher network activity. Furthermore, glial cells also play an important role in epileptic activity by regulating the K+ ion concentration in the extracellular space (D'Ambrosio, 2004, Lux, et al., 1986) and glial NKCC1 may be important for clearance of extracellular K+ (Chen and Sun, 2005). Thus, we wanted to re-address the role of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter using control saline conditions versus 4-aminopyridine as a convulsive agent, control conditions versus bumetanide as an inhibitor of the cotransporter, and wild-type versus NKCC1 knockout (Delpire, et al., 1999) hippocampal slices. To test the 4-AP seizure model, we also use brain slices from older animals, where KCC2 plays a key role in preventing hyperexcitability and where reduction of KCC2 expression by half leads to hyperexcitability in the slice model and increased seizure susceptibility in the whole animal (Woo, et al., 2002). In summary, our data show that NKCC1, as KCC2, prevents hyperexcitability and the development of seizures in the hippocampus. However, as NKCC1 was shown to not accumulate Cl− in young P9-P13 pyramidal neurons, the protective effect of NKCC1 is likely to occur through a mechanism or mechanisms independent of Cl− regulation in the pyramidal cells, such as working as an extracellular K+ clearance pathway or increasing intracellular [Cl−] of interneurons.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Animals

Mice used in these experiments were housed in microisolators in a standard animal care facility with a 12h light/dark cycle, and free access to food and water. All procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Animal Care and Use Committee in agreement with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2 Genotyping

Wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous KCC2 and NKCC1 mice were generated from heterozygous matings. Genotyping was performed by clipping 1 mm of the tail of P15 pups (from KCC2+/− parents) and P8 pups (from NKCC1+/− parents), by lyzing it in 200 μl solution containing 25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM EDTA, pH ∼ 12 for 20 min at 95°C, and neutralizing by adding of 200 μl solution containing 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH ∼ 5. Tail samples were then centrifuged for 6 min at 14,000 rpm, and 200 μl of supernatant was collected and saved for genotyping. Separate polymerase chain reactions were performed on 1-2 μl tail DNA to amplify fragments specific to the control and mutant genes. For KCC2, the oligonucleotide primers for the control gene were: forward 5' AGCGTGTGTCCGTGTGCG AGTG 3′ and reverse 5′ TTGTTGAGCATGGTGGC TGCGC 3′ oligonucleotide primers. For the mutant gene, the same forward primer was used while the reverse primer was 5′-CCAGAGGCCACTTGTGTAGCGC 3′. The reactions generate fragments of 207 and 204 bp, respectively. For NKCC1, the primers for the control gene were: forward 5' TATCTCAGGTGATCTTGC 3′ and reverse 5′ ACACTGCAATTCCTATGTAAACC 3′; and for the mutant gene: forward 5' TGCAACTGGTATTCTAGCTGGAGC 3' and reverse 5' TACAACACACACTCCAACCTCCG 3'. In this case, the sizes of the fragments are 184 bp and 497 bp, respectively.

2.3 Brain Slice Preparation

Brain slices were prepared from P9-P13 (when NKCC1 is highly expressed and functioning) NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− mice and P19-P25 (When KCC2 is highly expressed and functioning) KCC2+/+ and KCC2+/− mice. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. Following the dissection of the skull, the brain was rapidly removed and immersed in oxygenated (95%O2 /5%CO2) ice-cold high sucrose/high magnesium cutting solution of the following composition (in mM): sucrose 248, KCl 2.8, MgSO4 2.0, MgCl2 6.0, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, glucose 10 (PH 7.4) for less than 30 seconds. The brain was quickly lifted and glued onto a 4% agar block which was attached to a pre-chilled cutting stage. The stage was then mounted onto a vibratome (Vibratome, St. Louis, MO), and the cutting chamber was filled with oxygenated ice-cold cutting solution. Hippocampal transverse slices of 350-400 μm were cut and transferred to 37°C oxygenated artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM): NaCl 124, KCl 2.8, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, glucose 10. After 30 minutes incubation, the slices were gently transferred into room temperature oxygenated aCSF and kept for at least one hour before use.

2.4 Electrophysiology

All electrophysiological experiments were performed at 29-30°C in a submerged chamber perfused with oxygenated aCSF. For extracellular recordings, 4-6 MΩ pipette pulled from thin wall Borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, Fl) were filled with normal aCSF. The tip of the recording pipette was placed in the stratum pyramidale of CA3. For cell-attached experiments, the whole tip (from beginning to the end of taper) of the glass pipette (3-4 MΩ) was filled with gramicidin-free pipette solution containing (in mM): KCl 140, HEPES 10, pH 7.2. The pipette was then backfilled with pipette solution containing less than 5 μg/ml gramicidin D (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The seal resistance of the recordings was always equal to or higher than 5GΩ. Gramicidin was used to reduce the patch resistance (Rpatch) to a value much lower than the value for conventional cell-attached mode (Figure 1, and (Perkins, 2006)). With low gramicidin, the patch resistance drops to less than 200 MOhm in a few minutes and Vpipette reaches a value very close to the resting membrane potential (−65 to −75 mV). All recordings were done in current clamp mode with holding current set at 0, so that no artificial current is injected into the neuron from the headstage. Indeed, if current is injected, it will change the membrane potential of the recorded neuron (Perkins, 2006). Due to the high series resistance (the “patch resistance” in this cell-attached mode), it is not possible to plot an I/V relationship and calculate the GABA reversal potential (most of the voltage drop will be at the patch instead of the membrane).

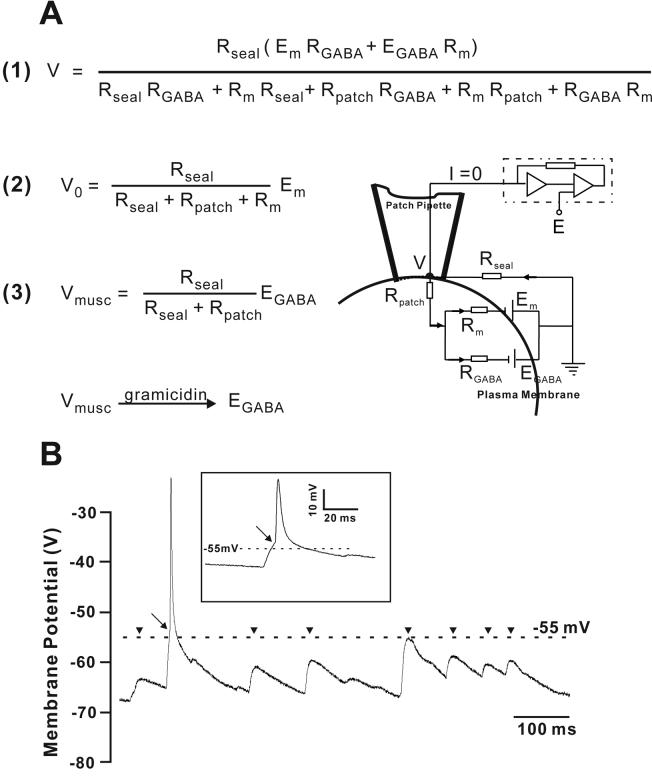

Figure 1.

The application of low-gramicidin cell-attached patch recording. (A) Relationship between the measured potential and the membrane potential. Drawn on the right side is the equivalent circuit of a cell-attached patch clamp. The recorded membrane potential, V, is represented by resistances and potentials in (1). When GABAA receptor is not activated, RGABA is infinite and the representation of V is reduced to (2). When GABAA receptor is activated and the cell membrane resistance is very large in young age CA3 pyramidal neurons, RGABA is insignificant compared to RSeal and the representation of V is reduced to (3). In our experiments, RPatch is significantly reduced by gramicidin perforation, thus RPatch can also be ignored and V is a very close representation of the actual EGABA. RSeal is the seal resistance, Rm is the whole cell membrane resistance, and RPatch is the patch resistance. When the cell is clamped at current zero, the two batteries and the seal shunting resistance form a closed circuit resistance, EGABA is the GABA reversal potential which can be obtained from the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation, RGABA is GABA resistance at peak muscimol response, and Em is the resting membrane potential. (B) Continuous measurement of membrane potential (V) by low-gramicidin cell-attached patch recording of a P13 CA3 pyramidal neuron. An action potential (arrow) is triggered at ∼ −55 mV (Principal of Neural Sciences, 4th edition, page 222,227) and the recorded resting membrane potential ranges from −65 to −75mV. Note that the action potential did not overshoot 0 mV, due to the artificial cut-off explained in (Perkins, 2006), and the recording in the cell body rather than axon. Depolarizations that did not reach threshold (arrowheads) failed to result in action potential firing. Inset shows the typical biphasic depolarization.

In the cell-attached patch mode, the recorded voltage (V) and the membrane potential (Em) have the relationship shown in Figure 1A. As Rseal is usually greater than 2 GΩ, and Rm (with the exception of very young neurons) is by and large uniform and low, the value of Rpatch typically determines the accuracy of the membrane potential measurement. V approximates Em when RPatch is negligible in comparison to RSeal (Perkins, 2006). Thus, by adding very low concentrations of gramicidin in the pipette solution (starting at less than 5 μg/ml in the back-filling solution and reaching much lower concentrations at the tip), RPatch can be minimized and V becomes a good approximation of Em at reasonable seal resistances. As mentioned above, due to the high resistance (Rm) of very young pyramidal neuron membranes (Tyzio, et al., 2003), this technique has limitations for measuring the membrane potential of very young neurons. However, at ages P9-P13, the membrane resistance is low enough for Em to be measure accurately. Indeed, the higher the membrane conductance is, the more accurate the measurement of the membrane potential is. Thus, in low gramicidin cell-attach patch recording, the peak of the muscimol response will approximate the GABA reversal potential (Figure 1A, equation 3). Using cell-attached recordings in current clamp mode (I = 0) and with low gramicidin in the pipette, we studied the spontaneous membrane activity of CA3 principal neurons. As seen in Figure 1B, the membrane potential can be followed accurately as the action potential threshold was measured at −56.6 ± 1.6 mV (n = 40 spikes from 4 CA3 pyramidal neurons). Furthermore, the measured resting membrane potential ranges between −60 mV to −75 mV, confirming the accuracy of this method.

All data were filtered by Bessel filter (0.1-2000Hz), amplified by multiclamp 700B and analyzed by pCLAMP 9.0 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Bumetanide (Sigma) was applied to perfusion aCSF from stock in DMSO to reach a final concentration of 10 μM. 4-aminopyridine (Sigma) was used at a final concentration of 50 μM in aCSF. Specific agonist of GABAA receptor muscimol (20μM in aCSF) was pressure delivered to the cell body using a picospritzer (General Valve Corporation, Fairfield, N.J.) via a glass pipette (3-4 MΩ). Unpaired t-test was used for the statistical analysis. Data were presented by mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

2.5 Western Blot

Wild-type mice of different ages were anesthetized, decapitated, and 500 μm brain slices were prepared following the procedure described above. Slices were then placed on an ice-cold metallic block and 0.41 mm tissue punches were taken from CA1 and CA3 hippocampus using a tissue puncher (VWR Scientific, West Chester, PA). Small volume of lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM TrisCl, pH 7.4, and 1 complete minitablet/10 ml protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) were added to the slices and the samples were homogenized using a Kontes pellet pestle grinder (VWR Scientific). Protein concentrations were quantitated using standard Bradford assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Protein samples were then denatured in SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 75°C for 20 min and separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were then transferred from the gels onto polyvinylidine fluoride membranes (BioRad), and the membranes blocked for 2 h at room temperature (RT) in TBST (NaCl, 150 mM; Tris-Cl, 10 mM, pH 8.0, Tween 20 [polyoxyethylene-sorbitan monolaurate], 0.5%) supplemented with 5% non-fat dry milk. Membranes were then incubated with anti-KCC2 (Lu, et al., 1999) or anti-tranferrin (TR) receptor (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) primary antibodies at 1:1000 dilution in blocking solution at 4°C overnight. Following extensive TBST washes, membranes were incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (KCC2) or anti-mouse (TR) secondary antibodies in blocking solution (1:4000; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at RT, and then rinsed for 2 h in TBST. Finally, protein bands detected by antibodies were visualized by chemiluminescence using ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL).

3. RESULTS

NKCC1 expression is highest in immature CNS and decreases during postnatal development towards adulthood (Kanaka, et al., 2001, Li, et al., 2002, Mikawa, et al., 2002, Plotkin, et al., 1997, Wang, et al., 2002). Due to the large inward Na+ and Cl− driving force, NKCC1 is a good candidate for intracellular Cl− accumulation in immature neurons and GABA excitatory effects. However, other evidences suggest that NKCC1 expression may not be ubiquitously down-regulated in all types of neurons during CNS development (Balakrishnan, et al., 2003, Wang, et al., 2002). Whether NKCC1 function has pro- or anti-epileptic properties is still a matter of controversy.

To assess the role of NKCC1 in regulating intracellular Cl− in developing hippocampus, we first attempted to use the gramicidin-perforated patch method in brain slices and determine the GABA reversal potential without disrupting the chloride gradient. Because of the positive pressure applied to the pipette while advancing into the slice and the relatively high concentration of gramicidin contained in the pipette, gramicidin often disrupted the GΩ seal. Furthermore, by leaking into the slice, the ionophore also produced depolarization of surrounding neurons. Therefore, instead of using the traditional gramicidin-perforated patch method well-suited for single cell recording, we modified the conventional cell-attached patch recording method (Mason, et al., 2005, Perkins, 2006) by adding a very low concentration of gramicidin in the pipette and record changes in membrane potential associated with the application of muscimol (see Material and Methods).

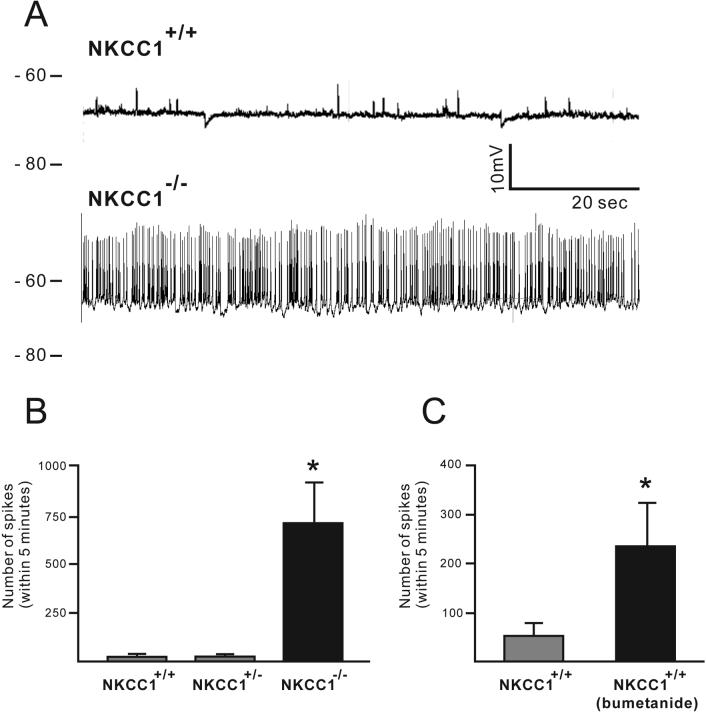

Because NKCC1−/− mice are viable and do not show any behavioral signs of seizure activity, we examined the spontaneous activity in brain slices prepared from wild-type, NKCC1+/− and NKCC1−/− mice. Under control perfusion conditions, we found that CA3 pyramidal neurons from P10 NKCC1−/− mice exhibited much higher action potential firing rates than the same neurons from P10 wild-type mice (Figure 2A). We then quantified the number of action potentials (AP) over a 5 min period. As shown in Figure 2B, there were 706 ± 210 AP spikes per five minutes in CA3 pyramidal neurons from NKCC1−/− mice (n = 7 from four P10-P13 mice), in comparison to 20 ± 9 AP spikes in neurons from wild-type mice (n = 8 from five P9-P13 mice, P = 0.0022). In addition, we tested whether bumetanide (10 μM), a potent inhibitor of NKCC1, would alter excitability in wild-type slices similar to NKCC1−/− slices. Five-minute time windows were taken from the recorded trace before or after perfusion of bumetanide (at least 15 minutes after the start of bumetanide). As seen in Figure 2C, the number of AP spikes recorded from CA3 pyramidal neurons after bumetanide treatment (237 ± 87, n = 9 from 8 mice) was significantly larger than the number of AP spikes measured using control aCSF (54 ± 25, n = 9 from 8 mice, P = 0.027). Together, these results show that AP firing rate has increased in the absence or blockade of NKCC1, indicating increased network activity. The membrane potentials of wild-type and NKCC1−/− neurons were −66 ± 0.8 mV (n = 8) and −62 ± 2.2 mV (n = 7), P = 0.03.

Figure 2.

Recordings of spontaneous action potential spikes from CA3 pyramidal neurons of wild-type and NKCC1−/− slices in normal aCSF. A: The number of action potential spikes is much higher than in NKCC1−/− slices than wild type slices. (B) The number of action potential spikes within 5 minutes of recording from NKCC1−/− slices (n = 7, 4 mice) is significantly larger than NKCC1+/− (n = 3, 2 mice) and wild type (n = 8, 5 mice). (C) In the presence of the loop diuretic bumetanide (10 μM), the number of action potential spikes within a 5 minute recording was significantly increased in wild type slices (n = 9, 8 mice).

As the driving force of chloride (aside of a smaller contribution of bicarbonate) determine the polarity of an evoked GABA response, the response of neurons to muscimol, a potent and selective agonist of ionotropic GABAA receptors but not metabotropic GABAB receptors can be compared between wild-type and NKCC1−/− neurons to assess whether [Cl−]i is affected. While the majority of excitatory glutamatergic synapses are located on the dendrites of the pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, a great portion of inhibitory GABAergic synapses are formed on the proximal dendrites or the cell soma. In the following experiments, we applied short puffs (6-8 ms) of muscimol (20 μM) onto the cell soma to evoke responses from GABA receptors. When P10-old wild-type CA3 pyramidal neurons were current-clamped at zero current, muscimol puffs evoked a slight hyperpolarization of the membrane potential from −54.5 mV to −59.5 mV (Figure 3A1), indicating that the driving force for chloride is inward. Differences between neurons in the muscimol peak response were due to variations in resting membrane potentials (Figure 3B), and differences between muscimol responses and membrane potentials (Vdelta) were under 10 mV (Figure 3C). Interestingly, there was little difference in the Vdelta between NKCC1−/− neurons (−1.8 ± 2.6 mV, n = 3) and wild-type neurons (0.1 ± 2.8 mV, n = 3, P > 0.05, not significant). Given that the extracellular bicarbonate concentration and extracellular pH are identical in all experiments, the difference in Vdelta indicates the difference in the chloride driving force.

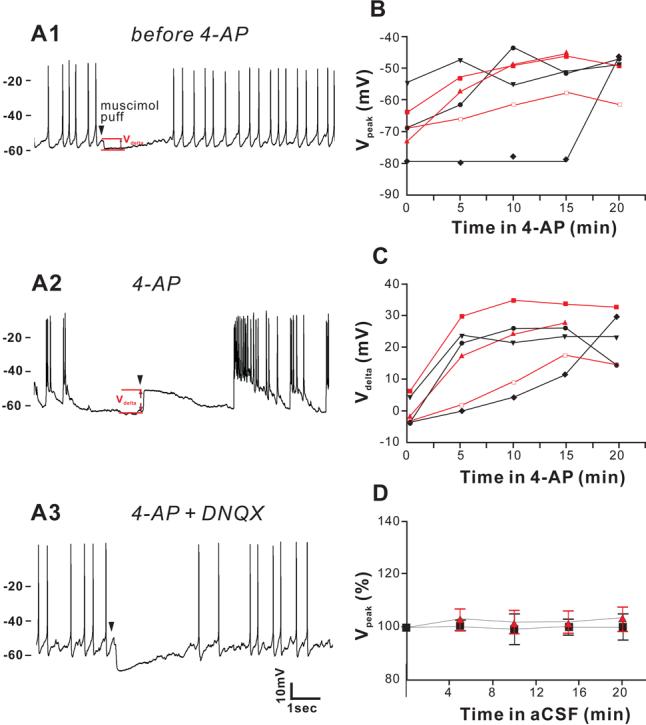

Figure 3.

Muscimol induces larger depolarization upon treatment with 4-AP, and this shift in muscimol response is reversed by suppressing the seizure-like events with DNQX. (A), In a CA3 pyramidal neuron from P10 mouse, brief (8ms) muscimol application induced larger membrane depolarization (12.8 mV, from −63.8mV to −51.0 mV) after being perfused for10 minutes with 50 μM 4-AP (A2), compared to the slight hyperpolarization from −54.5mV to −59.5mV induced by same muscimol application in control aCSF (A1). This shift of muscimol response is abolished by 20 μM DNQX (4-AP still present) (A3). Arrowhead indicates the time of the muscimol application. (B) Under 4-AP application, muscimol was applied to the cell every 5 minutes, and responses were recorded. The absolute peaks of muscimol response (Vpeak) shifted to more depolarized potentials in the presence of 4-AP in both NKCC1−/− (red symbols and lines, n = 3 from 3 mice) and wild type slices (dark symbols and lines, n = 3 from 3 mice). (C) The amount of depolarization (or hyperpolarization) (Vdelta) induced by muscimol also increase in the presence of 4-AP for both NKCC1−/− and wild type slices. (D) When 4-AP is not applied, the peak of hyperpolarization remains stable during 10 minutes of recording in both wild-type and NKCC1−/− slices.

Blocking voltage-gated potassium channels with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) is a well-established model to increase the release of excitatory neurotransmitter and trigger epileptiform discharges and seizure-like events in hippocampal slices. Upon addition of 4-AP to the perfusing solution, the same application of muscimol induced a depolarization of the Vpeak (−63.8 mV to −51.0 mV) along with increased activity and interictal-like events in the slice (Figure 3A2). Hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential is known to be an effect of 4-AP and is not significantly different between NKCC1−/− and WT (NKCC1−/−, −65.83 ± 4.7 mV, −77.72 ± 3.5 mV, −75.76 ± 3.4 mV, −80.61 ± 4.7 mV at 0, 5, 10, 15 minutes after 4-AP application respectively; WT, −68.36 ± 1.6 mV, −74.95 ± 4.5 mV, −75.69 ± 4.3 mV, −75.99 − 2.2 mV at 0, 5, 10, 15 minutes after 4-AP application, respectively). This spontaneous hyperpolarization of the membrane is probably due to increased GABAB receptor-mediated activation of membrane conductance to K+ (Avoli, et al., 1994, Jarolimek, et al., 1994). Under 4-AP application, the driving force of chloride rapidly reversed its direction and GABA became excitatory. Again, there was no measurable difference in Vdelta between P10-P13 NKCC1−/− neurons (16.2 ± 8.1 mV, 22.7 ± 7.5 mV, and 26.4 ± 5 mV at 5, 10, 15 min respectively, n = 3), and P11-P13 wild-type neurons (14.6 ± 7.6 mV, 16.8 ± 6.8 mV, and 20.0 ± 4.6 mV at 5, 10, 15 min respectively, n = 3) after 4-AP treatment (Figure 3C). Both the change in EGABA and the hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential contribute to the change of Vdelta after 4-AP application (Figure 3B). Of interest is the fact that the 4-AP induced change in EGABA is rapidly eliminated upon addition of 20 μM DNQX, a potent antagonist of non-NMDA glutamatergic receptors (Figure 3A3). During control conditions in which 4-AP is not used, peak hyperpolarization remains stable in both wild-type and NKCC1−/− cells (Figure 3D). These results indicate that although NKCC1 accumulates chloride in neurons, the cotransporter had little effect on the chloride driving force in CA3 pyramidal neurons from P10-P13 mice in the presence of increased network activity induced by 4-AP.

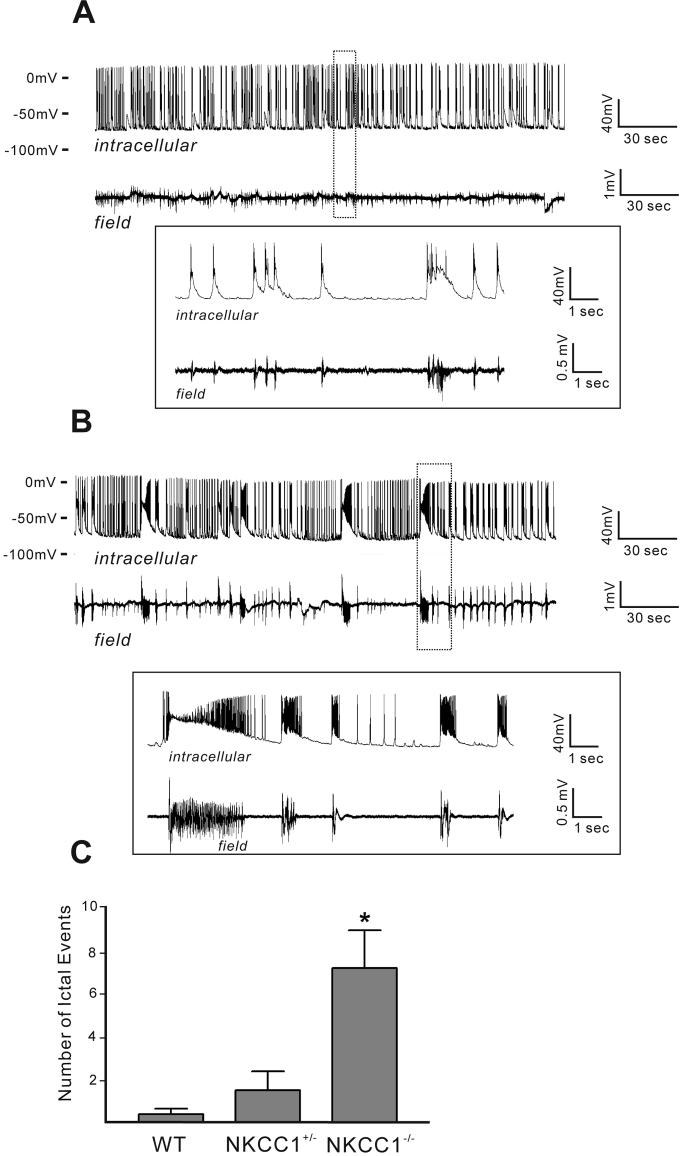

Since CA3 neurons isolated from NKCC1−/− mice demonstrate hyperexcitability when compared to wild-type CA3 neurons, we tested the effect of 50 μM 4-AP in the two genotypes (Figure 4). Cell-attached recordings (upper traces of Panels 4A and 4B) and extracellular field recordings (lower traces of Figure 4A and 4B) were carried out simultaneously in the CA3 region of the hippocampus. Shortly after the application of 4-AP, ictal-like epileptiform activities arose in NKCC1−/− slices (Figure 4B), whereas only interictal-like activities appeared in wild-type slices (Figure 4A). Both the ictal-like and interictal-like events were synchronized between cellular recordings and local field recordings (Figure 4A-B), indicating that network activity was recorded in the cell-attached mode. The ictal-like epileptic events seen in NKCC1−/− slices consist of a tonic and a clonic phase. We quantified the number of seizure-like events during the first 15 min after addition of 4-AP to the perfusing solution (Figure 4C). In P10-P13 NKCC1−/− slices, we recorded 7.2 ± 1.8 seizure-like epileptic events (n = 6, from 3 mice). This number is significantly greater than the number of ictal events recorded in wild-type slices (0.4 ± 0.2, n = 8 from 4 mice). Of interest, the number of seizure-like events in P11-P12 NKCC1+/− mice is closer to wild-type slices: 1.5 ± 0.9 (n = 4 from 2 mice). These results indicate that, instead of facilitating seizure activity, NKCC1 actually inhibits the generation of seizures. Removing NKCC1 inhibition lowers the seizure inducing threshold and facilitates the development of seizure activity at this developmental stage.

Figure 4.

4-AP induces more ictal events in NKCC−/− slices than in wild type slices. 4-AP application increases the level of spontaneous activities in both wild-type (A) and NKCC1−/− slices (B), but ictal events (20-40 seconds duration) are more often seen in NKCC1−/− slices. Cell-attached recording from CA3 pyramidal neurons (upper traces) and field recordings from CA1 stratum pyramidale (lower traces) show that the ictal events are synchronized (B). Insets in (A) and (B) are expanded traces from regions indicated by the dotted box. (C) The number of ictal events (duration > 20 seconds) of NKCC−/− slices (7.2 ± 1.8, n= 6 from 3 mice, P10-P13) are significantly greater than that of wild type slices (0.4 ± 0.2, n=8 from 4 mice, P10-P13). The number of ictal events seen in NKCC1+/− slices is 1.5 ± 0.9 (n= 4 from 2 mice, P11-P12).

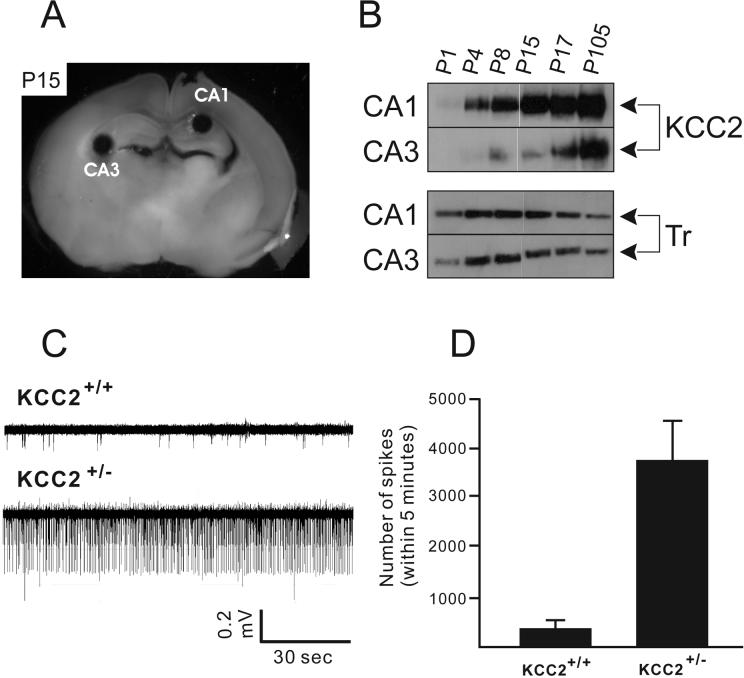

Because we used the 4-AP model for the first time in our experiments with wild-type and NKCC1 mutant mice, we wanted to test this model with KCC2 heterozygous animals previously shown to be prone to epileptic seizures (Woo, et al., 2002). Many studies have examined the spatial and temporal distribution of KCC2 mRNA transcript and protein during postnatal development (Clayton, et al., 1998, Lu, et al., 1999, Mikawa, et al., 2002, Rivera, et al., 1999, Shimizu-Okabe, et al., 2002, Wang, et al., 2002). There is consensus showing that KCC2 expression in rodents is low at birth in the forebrain, and increases steadily during the first 2-3 weeks of postnatal life. To examine the level of KCC2 expression in the regions of hippocampus where our electrophysiological measurements were made, we acquired tiny amount of tissue samples from either CA1 or CA3 by making 0.41mm-diameter punches. Figure 5B shows that KCC2 protein in the CA1 region increases steadily. It is undetectable at postnatal day P1 and increases towards adult level during the first two postnatal weeks (Figure 5B). In the CA3, KCC2 expression is much lower than in the CA1 during the first 2 postnatal weeks and then increases thereafter. Western blots were reprobed using anti-transferrin receptor to verify that punches were made in the neuronal layers. To assess the role of KCC2 in the excitability of the hippocampus, we performed extracellular field recordings in brain slices isolated from wild-type and KCC2+/− mice under control and 4-aminopyridine conditions. Extracellular recordings were obtained from the hippocampus CA1 sub-region. In control aCSF, fewer spontaneous events were identified in wild-type slices compared to KCC2+/− slices (Figure 5C), which express one half of the KCC2 protein content of wild-type animals (Woo, et al., 2002). At age P19-P25, when KCC2 is highly expressed in wild-type brain, expression of only one copy of KCC2 results in increased spontaneous activity, as demonstrated by a significantly larger number of spikes (Figure 5D, P = 0.0078).

Figure 5.

(A-B) Postnatal expression pattern of KCC2 protein in the CA1 and CA3 regions. (A) Example of 0.41 mm sample punches taken from CA1 and CA3 hippocampal regions in a 500 μm whole brain slice from a P15 wild-type mouse. (B) Expression of KCC2 in CA1 hippocampus increases gradually from P1 to P17, but remains low in the CA3 until P17. P105 shows the level of KCC2 in the adult mouse. Anti-transferrin receptor antibody was used as control. (C-D) Recording of spontaneous spikes from wild type and KCC2+/− slices in normal aCSF. Both the amplitude and frequency of extracellularly recorded spontaneous events are increased in slice from a KCC2+/− mouse (P18) compared to wild type mouse (P19) (C). No drugs are added to the perfusion during the recording. (D) Pooled data from both wild type and KCC2+/− slices. Number of spikes within 5 min are counted and analyzed. KCC2+/− slices have a higher occurrence of spontaneous events (3773 ± 805; n = 6, 2 mice) than wild-type slice (377 ± 144; n = 6, 2 mice).

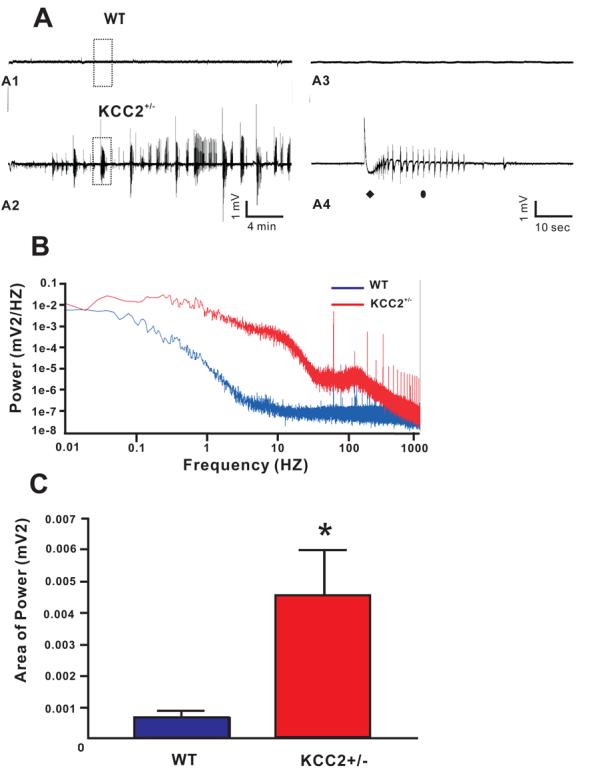

As seen in Figure 6A2, 4-AP induced seizure-like events in CA1 substructure of hippocampus in brain slices isolated from P24 KCC2+/− mice. Each event was typically longer than 20 seconds and consisted of an interictal, tonic, and clonic phase (Figure 6A4). In contrast, 4-AP treatment only induced interictal-like events in slices isolated from wild-type mice (Figure 6A1, A3), and in some slices induces ictal events lasting less than 5 seconds in duration (data not shown). Figure 6B shows the power spectra for twenty minutes of consecutive recordings of CA1 hippocampus from wild-type and KCC2+/− slices (traces taken from Figures A1 and A2). Power spectrum analysis shows that the power density in KCC2+/− was greater than in wild-type, in the EEG frequency band (1-100HZ), as well as in the fast ripple frequency band (200-400HZ). To quantify seizure susceptibility of KCC2+/− brain slices and wild-type brain slices, the area under the power spectrum for frequencies ranging from 1-100HZ was measured for each recording, and averaged from seven 1-min windows for each traces, 10 min after the application of 4-AP (Figure 6C). The power obtained from KCC2+/− CA1 hippocampal recordings (4.6 ± 1.4) × 10−3 mV2 (n = 6 from 5 mice, P19-P25) was significantly greater than the power obtained from wild-type CA1 hippocampal recordings: (6.9 ± 2.4) × 10−4 mV2, n = 5 from 4 mice, P18-P24, P = 0.038). However, the power obtained for KCC2+/− and wild-type recordings before treatment with 4-AP (baselines) were not significantly different (data not shown). These results indicate that a reduction in KCC2 expression increases the susceptibility of the hippocampus to seizure-inducing agents such as 4-AP.

Figure 6.

Extracellular field recording shows 4-AP induces more seizure-like activities in CA1 region of hippocampal slices from KCC2+/− mice. (A) 4-AP induces seizure-like events in KCC2+/− brain slice (P24, A2), but much less activities in its wild type counterpart (P24, A1). The boxed region is expanded in A3 and A4 for wild type and KCC2+/−, respectively. Each seizure-like event in the KCC2+/− slices consists of a tonic phase (filled diamond) and clonic phase (filled oval). (B) Power spectra from the two traces of (A) in consecutive 20 minutes time windows (window starts at 10 minutes after 4-AP application). EEG (1-100 HZ) and fast ripple (200-400 HZ) frequency range are shown. (C) Average power of extracellular field activity (1-100 HZ band) in 1 minute windows of seizure-like events region 10 minutes after 4-AP application Wild-type: 5 slices from 4 mice P18-24; KCC2+/−: 6 slices from 5 mice P19-25.

4. DISCUSSION

Recent studies have uncovered multiple roles for the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, NKCC1, in volume and ion homeostasis in the brain, and in diverse pathologies of the CNS. For instance, the endothelial NKCC1 is involved in the increased salt and fluid movement into the brain that is associated with ischemic brain injury (Chen and Sun, 2005, Pedersen, et al., 2006). Furthermore, the cotransporter is also involved in glial cell swelling and glutamate release, leading to neuronal excitotoxicity (Chen, et al., 2005, Chen and Sun, 2005, Su, et al., 2002, Su, et al., 2002). The role of NKCC1 in central neurons is still controversial. Based on an overall decrease in NKCC1 expression during postnatal development, measured by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence, we proposed in 1997 that NKCC1 might accumulate intracellular Cl− above the concentration predicted by its electrochemical equilibrium potential (Plotkin, et al., 1997). Indeed, NKCC1 is a well-established mechanism of Cl− accumulation in sensory DRG neurons (Achilles, et al., 2007, Alvarez-Leefmans, et al., 1988, Chub, et al., 2006, Rohrbough and Spitzer, 1996, Sung, et al., 2000). Accumulation of Cl− through the cotransporter is possible due to the large Na+ gradient generated by the Na+/K+ pump. The combination of down-regulation of NKCC1 expression and up-regulation of KCC2 expression would account for the Cl− decrease from values above electrochemical potential equilibrium to values below. In fact, in P2-P4 cortical and hippocampal neurons, NKCC1 accumulates Cl−, as bumetanide application results in >10 mV hyperpolarizing shift in the GABA reversal potential (Sipila, et al., 2006, Yamada, et al., 2004). However, recent studies in auditory brainstem neurons (Balakrishnan, et al., 2003) and retinal neurons (Zhang, et al., 2007) have demonstrated that NKCC1 is not involved in the Cl− accumulation, as high Cl− concentrations were still measured in the absence of NKCC1. Whether or not the cotransporter accumulates Cl− in some central neurons but not in others is still a matter of debate. One critical issue related to the measurement of internal Cl− in brain tissue is the accuracy of GABA reversal potential measurements, especially in young neurons that have high membrane resistance. The gramicidin perforated patch clamp is certainly the most used electrophysiological method to assess the intracellular Cl− concentration in neurons. In isolated cells, the method is relatively straightforward as application of positive pressure is of little necessity during the advancing of the pipette towards the cell body. However, in brain slice experiments, as the pipette has to find its way through connective tissues and debris, positive pressure is often applied. To avoid leak of gramicidin due to the positive pressure, gramicidin-free pipette solution is typically placed into the tip of the pipette whereas the gramicidin-containing pipette solution is backfilled. This maneuver eventually lowers the effective gramicidin concentration in contact with the membrane patch. In gramicidin perforated patch recordings, there is a dilemma that even though high concentration of gramicidin lowers the series resistance and reduces the time for it to stabilize, it also increases the chance of spontaneous ruptures in the patch and disrupt the intracellular [Cl−].To resolve this problem, we modified the cell-attached patch clamp at zero current (I = 0) by adding very little amount of gramicidin in the pipette solution (<5 μg/ml in the backfilling solution, so the final gramicidin concentration that reaches the very tip being much lower). According to Perkins (Perkins, 2006), the ratio between patch resistance and seal resistance is the determining factor of the confidence of measuring membrane potential. By including low concentrations of gramicidin, the patch resistance is reduced significantly in comparison to the GΩ seal, and the recorded membrane potential becomes very close to actual membrane potential. At P9-P13, when NKCC1 expression is still relatively high (Dzhala, et al., 2005), and KCC2 expression has not yet increased (Figure 5B), we show that the muscimol-mediated response is very small in the pyramidal CA3 neuron, indicating the GABA reversal potential is close to the resting membrane potential(Figure 3C). Furthermore, bumetanide only changed slightly (in the positive direction) these muscimol-induced responses (data not shown, but in agreement with (Banke and McBain, 2006, Dzhala, et al., 2005)), indicating that NKCC1 is not accumulating Cl− above its equilibrium potential in these pyramidal cells

Despite the fact that NKCC1 activity does not results in high [Cl−]i at P9-P13, we showed that absence of NKCC1 resulted in significant hyperexcitability, as the number of action potential measured per unit of time increased significantly (Figure 2B). Because we were examining the brain of a knockout animal which might have developmental abnormalities, we treated wild-type slices with bumetanide, an inhibitor of the cotransporter with a Ki ranging from 0.5-2 μM. Treatment of wild-type slices with 10 μM bumetanide also induced a significant increase in the number of action potentials measured per unit of time (Figure 2C), indicating that the increased hyperexcitability observed in the knockout resulted directly from the absence of the cotransporter rather than from developmental abnormalities.

The increase spontaneous electrical activity of pyramidal CA3 neurons in NKCC1−/− slices therefore suggests a different role for the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. One possible role is the regulation of external K+ concentration by glial NKCC1 during neuronal activity. As cells are tightly packed in vivo and in brain slices, the K+ concentration in the extracellular space can increase rapidly during neuronal activity (Avoli, et al., 1993, Louvel, et al., 1994, Nicholson and Hounsgaard, 1983, Roberts and Feng, 1996). Several studies performed in isolated astrocytes have demonstrated involvement of NKCC1 in the clearance of K+ (Hertz, 1978, Su, et al., 2002, Su, et al., 2002, Tas, et al., 1987, Walz and Hertz, 1984). Thus, absence of the cotransporter in glial cells would reduce the rate of clearance of K+ during synaptic activity, resulting in the accumulation of the cation in the extracellular space and hyperexcitability. Alternatively, differential expression of NKCC1 in inhibitory neurons could regulate their excitability, and, if so, its reduction in the knockout mouse or with bumetanide would result in hyperexcitability by decreasing inhibitory tone.

In this study, we also made use of 4-aminopyridine as seizure-inducing agent. We showed that addition of 50 μM 4-AP induced hyperexcitability in both wild-type and NKCC1−/− slices (Figures 3A2 & 4). Consistent with the hyperexcitability demonstrated in CA3 pyramidal cells from NKCC1−/− mice or from wild-type mice in the presence of bumetanide, 4-AP induced seizure-like activity in CA3 pyramidal neurons. These seizure activities, synchronous between CA3 and CA1, were rarely seen in wild-type slices under 4-AP treatment. These data confirm that NKCC1 in P9-P13 wild-type brains actively participate in preventing hyperexcitability and the development of uncontrolled, synchronous seizure-like activity. Thus, our data are contrary to those of Dzhala and coworkers who suggested that NKCC1 expression instead facilitates the development of seizures in the juvenile brain (Dzhala, et al., 2005). However, they used high extracellular K+ (8.5 mM) to induce seizure activity. This high external K+ concentration alters the function of NKCC1 by increasing the inward driving force for chloride ions. High K+ also alters the function of KCC2, even though its expression level is relatively low in the developing brain (DeFazio, et al., 2000, Rivera, et al., 1999). However, in our study, we found that considerable amount of KCC2 has been expressed in the CA3 region of hippocampus (Figure 5B).High external K+ also leads to the accumulation of ions and water in glial cells, and to the release of excitotoxic glutamate (Chen and Sun, 2005). Prevention of this effect in the NKCC1 knockout mouse or by applying the NKCC1 inhibitor, bumetanide, might have contributed to the conclusion that NKCC1 promotes hyperexcitability in the juvenile brain (Dzhala, et al., 2005).

At the age when KCC2 expression in the forebrain is much lower than its expression level in the adult CNS, the intracellular chloride level of principal neurons was dramatically affected by the level of neuronal activity in the hippocampus. Indeed, in both NKCC1−/− and wild-type neurons, when hyperactivity and frequent membrane depolarization were induced by 4-aminopyridine, the muscimol response shifted from slightly inward to strongly outward, indicating a rise in the intracellular chloride concentration (given that [HCO3−]i is not expected to change under 4-AP and that [HCO3−]i has a lesser impact on EGABA when [Cl−]i is high). This increase in intracellular chloride is likely caused by the chloride influx through the extra-synaptic tonic GABA receptor channels or synaptic GABA receptor channels, or both, during the frequent depolarization of membrane potential. These data indicate the lack of a robust mechanism (not enough expression of activity of KCC2) to regulate intracellular Cl− and counter the challenge from Cl− flux through GABA receptor channels. These data are also consistent with previous findings in isolated cortical neurons (Zhu, et al., 2005) or auditory brain stem neurons (Ehrlich, et al., 1999), that showed that young neurons are unable to handle large shifts in the intracellular Cl− concentration. The change in the driving force measured under 4-AP (more than 20 mV) is large enough to produce GABA excitatory responses. Furthermore, the hyperpolarization in resting membrane potential (a side effect of 4-AP) also contributes to increased Cl− driving force (Avoli and Perreault, 1987, Avoli, et al., 1993). The increase in intracellular chloride was fully activity dependent as it could be reversed by blocking non-NMDA glutamate receptors with the antagonist DNQX (Figure 6A3).

In this study, we have also seen increased frequency of seizure-like activities in CA1 KCC2+/− slices in comparison to wild-type slices in the presence of 4-AP, thus confirming the increased susceptibility to seizure in KCC2+/− mice that was previously reported by us (Woo, et al., 2002). Given the importance of the hippocampus in epileptic seizures, and together with the lack of specific inhibitor of KCC2 and the lethality of the KCC2 knockout mouse, the KCC2+/− mouse also provides an excellent model for further studies of seizure development. In summary, we have shown that both NKCC1 and KCC2 participate in important neuronal function as mechanisms preventing the development of hippocampal epileptiform activity.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS36758) to E. Delpire.

6. REFERENCES

- Achilles K, Okabe A, Ikeda M, Shimizu-Okabe C, Yamada J, Fukuda A, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Kinetic properties of Cl uptake mediated by Na+-dependent K+-2Cl cotransport in immature rat neocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8616–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5041-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Gamiño SM, Giraldez F, Nogueron I. Intracellular chloride regulation in amphibian dorsal root ganglion neurons studied with ion-selective microelectrodes. J. Physiol. (Lond) 1988;406:225–246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E, Boer K, Redeker S, Spliet WG, van Rijen PC, Troost D, Gorter JA. Differential expression patterns of chloride transporters, Na+-K+-2Cl−-cotransporter and K+-Cl−-cotransporter, in epilepsy-associated malformations of cortical development. Neuroscience. 2007;145:185–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Mattia D, Siniscalchi A, Perreault P, Tomaiuolo F. Pharmacology and electrophysiology of a synchronous GABA-mediated potential in the human neocortex. Neuroscience. 1994;62:655–66. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Perreault P. A GABAergic depolarizing potential in the hippocampus disclosed by the convulsant 4-aminopyridine. Brain Res. 1987;400:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Psarropoulou C, Tancredi V, Fueta Y. On the synchronous activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the CA3 subfield of juvenile rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1018–1029. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan V, Becker M, Lohrke S, Nothwang HG, Guresir E, Friauf E. Expression and function of chloride transporters during development of inhibitory neurotransmission in the auditory brainstem. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4134–4145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04134.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banke TG, McBain CJ. GABAergic input onto CA3 hippocampal interneurons remains shunting throughout development. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:11720–11725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2887-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:728–739. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. [GABA, a key transmitter for fetal brain maturation] Med Sci (Paris) 2007;23:751–5. doi: 10.1051/medsci/20072389751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1215–84. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Luo J, Kintner DB, Shull GE, Sun D. Na(+)-dependent chloride transporter (NKCC1)-null mice exhibit less gray and white matter damage after focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:54–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Sun D. The role of Na-K-Cl co-transporter in cerebral ischemia. Neurol. Res. 2005;27:280–286. doi: 10.1179/016164105X25243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Sun D. The role of Na-K-Cl co-transporter in cerebral ischemia. Neurol Res. 2005;27:280–6. doi: 10.1179/016164105X25243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chub N, Mentis GZ, O'Donovan M J. Chloride-sensitive MEQ fluorescence in chick embryo motoneurons following manipulations of chloride and during spontaneous network activity. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:323–30. doi: 10.1152/jn.00162.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton GH, Owens GC, Wolf JS, Smith RL. Ontogeny of cation-Cl− cotransporter expression in rat neocortex. Brain Research. Developmental Brain Research. 1998;109:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosio R. The role of glial membrane ion channels in seizures and epileptogenesis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;103:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio RA, Keros S, Quick MW, Hablitz JJ. Potassium-coupled chloride cotransport controls intracellular chloride in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8069–8076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08069.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E, Lu J, England R, Dull C, Thorne T. Deafness and imbalance associated with inactivation of the secretory Na-K-2Cl co-transporter. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:192–195. doi: 10.1038/9713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala VI, Staley KJ. Excitatory actions of endogenously released GABA contribute to initiation of ictal epileptiform activity in the developing hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1840–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01840.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala VI, Talos DM, Sdrulla DA, Brumback AC, Mathews GC, Benke TA, Delpire E, Jensen FE, Staley KJ. NKCC1 transporter facilitates seizures in the developing brain. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1205–1213. doi: 10.1038/nm1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Lohrke S, Friauf E. Shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing glycine action in rat auditory neurones is due to age-dependent Cl− regulation. J. Physiol. (London) 1999;520:121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Muramatsu K, Okabe A, Shimano Y, Hida H, Fujimoto I, Nishino H. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ induced by GABAA receptor activation and reduction in Cl− gradient in neonatal rat neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:439–446. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L. An intense potassium uptake into astrocytes, its further enhancement by high concentrations of potassium, and its possible involvement in potassium homeostasis at the cellular level. Brain Res. 1978;145:202–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner CA, Stein V, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Meyer T, Ballanyi K, Jentsch TJ. Disruption of KCC2 reveals an essential role of K-Cl cotransport already in early synaptic inhibition. Neuron. 2001;30:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Toyoda H, Yamada J, Okabe A, Sato K, Hotta Y, Fukuda A. Differential development of cation-chloride cotransporters and Cl− homeostasis contributes to differential GABAergic actions between developing rat visual cortex and dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Brain Res. 2003;984:149–59. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarolimek W, Bijak M, Misgeld U. Differences in the Cs block of baclofen and 4-aminopyridine induced potassium currents of guinea pig CA3 neurons in vitro. Synapse. 1994;18:169–77. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaka C, Ohno K, Okabe A, Kuriyama K, Itoh T, Fukuda A, Sato K. The differential expression patterns of messenger RNAs encoding K-Cl cotransporters (KCC1,2) and Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC1) in the rat nervous system. Neuroscience. 2001;104:933–946. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazipov R, Khalilov I, Tyzio R, Morozova E, Ben-Ari Y, Holmes GL. Developmental changes in GABAergic actions and seizure susceptibility in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:590–600. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilb W, Sinning A, Luhmann HJ. Model-specific effects of bumetanide on epileptiform activity in the in-vitro intact hippocampus of the newborn mouse. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:524–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Tornberg J, Kaila K, Airaksinen MS, Rivera C. Patterns of cation-chloride cotransporter expression during embryonic rodent CNS development. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;16:2358–2370. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YW, Mee EW, Bergin P, Teoh HH, Connor B, Dragunow M, Faull RL. Adult neurogenesis in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a review of recent animal and human studies. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2007;8:187–94. doi: 10.2174/138920107780906504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco JJ, Owens DF, Heath MJS, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron. 1995;15:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvel J, Avoli M, Kurcewicz I, Pumain R. Extracellular free potassium during synchronous activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the juvenile rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1994;167:97–100. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)91036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Karadsheh M, Delpire E. Developmental regulation of the neuronal-specific isoform of K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 in postnatal rat brains. J. Neurobiol. 1999;39:558–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Prince DA. Postnatal maturation of the GABAergic system in rat neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1991;65:247–263. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux HD, Heinemann U, Dietzel I. Ionic changes and alterations in the size of the extracellular space during epileptic activity. Adv. Neurol. 1986;44:619–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty S, Wehrle R, Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Gasnier B, Sotelo C. Postnatal maturation of Na+, K+, 2Cl− cotransporter expression and inhibitory synaptogenesis in the rat hippocampus: an immunocytochemical analysis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;15:233–245. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ, Simpson AK, Mahaut-Smith MP, Robinson HP. The interpretation of current-clamp recordings in the cell-attached patch-clamp configuration. Biophys. J. 2005;88:739–750. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikawa S, Wang C, Shu F, Wang T, Fukuda A, Sato K. Developmental changes in KCC1, KCC2 and NKCC1 mRNAs in the rat cerebellum. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2002;136:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C, Hounsgaard J. Diffusion in the slice microenvironment and implications for physiological studies. Fed. Proc. 1983;42:2865–2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:6414–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SF, O'Donnell M,E, Anderson SE, Cala PM. Physiology and pathophysiology of Na+/H+ exchange and Na+ -K+ -2Cl− cotransport in the heart, brain, and blood. Am. J. Physiol. (Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.) 2006;291:R1–R25. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00782.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KL. Cell-attached voltage-clamp and current-clamp recording and stimulation techniques in brain slices. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2006;154:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin MD, Snyder EY, Hebert SC, Delpire E. Expression of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter is developmentally regulated in postnatal rat brains: a possible mechanism underlying GABA's excitatory role in immature brain. J. Neurobiol. 1997;33:781–795. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19971120)33:6<781::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Represa A, Ben-Ari Y. Trophic actions of GABA on neuronal development. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts EL, Feng ZC. Influence of age on the clearance of K+ from the extracellular space of rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1996;708:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbough J, Spitzer NC. Regulation of intracellulat Cl− levels by Na+-dependent Cl− cotransport distinguishes depolarizing from hyperpolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses in spinal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:82–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00082.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu-Okabe C, Yokokura M, Okabe A, Ikeda M, Sato K, Kilb W, Luhmann HJ, Fukuda A. Layer-specific expression of Cl− transporters and differential [Cl−]i in newborn rat cortex. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2433–2437. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200212200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipila ST, Schuchmann S, Voipio J, Yamada J, Kaila K. The cation-chloride cotransporter NKCC1 promotes sharp waves in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. (Lond) 2006;573:765–773. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein V, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Jentsch TJ, Hubner CA. Expression of the KCl cotransporter KCC2 parallels neuronal maturation and the emergence of low intracellular chloride. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;468:57–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su G, Kintner DB, Flagella M, Shull GE, Sun D. Astrocytes from Na(+)-K(+)-Cl(−) cotransporter-null mice exhibit absence of swelling and decrease in EAA release. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1147–C1160. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00538.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su G, Kintner DB, Sun D. Contribution of Na(+)-K(+)-Cl(−) cotransporter to high-[K(+)](o)- induced swelling and EAA release in astrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1136–C1146. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00478.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung K-W, Kirby M, McDonald MP, Lovinger DM, Delpire E. Abnormal GABAA-receptor mediated currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons isolated from Na-K-2Cl cotransporter null mice. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7531–7538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07531.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tas PWL, Massa PT, Kress HG, Koschel K. Characterization of an Na+/K+/Cl− co-transport in primary cultures of rat astrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;903:411–416. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzio R, Ivanov A, Bernard C, Holmes GL, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R. Membrane potential of CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells during postnatal development. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2964–2972. doi: 10.1152/jn.00172.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz W, Hertz L. Intense furosemide-sensitive potassium accumulation in astrocytes in the presence of pathologically high extracellular potassium levels. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1984;4:301–304. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1984.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Shimizu-Okabe C, Watanabe K, Okabe A, Matsuzaki H, Ogawa T, Mori N, Fukuda A, Sato K. Developmental changes in KCC1, KCC2, and NKCC1 mRNA expressions in the rat brain. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2002;139:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00536-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo N-S, Lu J, England R, McClellan R, Dufour S, Mount DB, Deutch AY, Lovinger DM, Delpire E. Hyper-excitability and epilepsy associated with disruption of the mouse neuronal-specific K-Cl cotransporter gene. Hippocampus. 2002;12:258–268. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J, Okabe A, Toyoda H, Kilb W, Luhmann HJ, Fukuda A. Cluptake promoting depolarizing GABA actions in immature rat neocortical neurones is mediated by NKCC1. J. Physiol. (Lond) 2004;557:829–841. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LL, Delpire E, Vardi N. NKCC1 does not accumulate chloride in developing retinal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:266–177. doi: 10.1152/jn.00288.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Lovinger D, Delpire E. Cortical neurons lacking KCC2 expression show impaired regulation of intracellular chloride. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1557–1568. doi: 10.1152/jn.00616.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]