Abstract

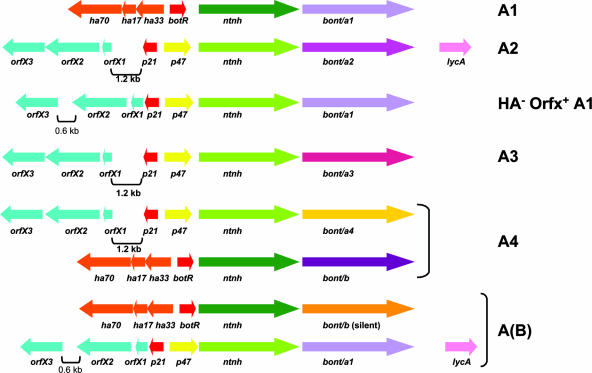

Neurotoxin cluster gene sequences and arrangements were elucidated for strains of Clostridium botulinum encoding botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) subtypes A3, A4, and a unique A1-producing strain (HA− Orfx+ A1). These sequences were compared to the known neurotoxin cluster sequences of C. botulinum strains that produce BoNT/A1 and BoNT/A2 and possess either a hemagglutinin (HA) or an Orfx cluster, respectively. The A3 and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains demonstrated a neurotoxin cluster arrangement similar to that found in A2. The A4 strain analyzed possessed two sets of neurotoxin clusters that were similar to what has been found in the A(B) strains: an HA cluster associated with the BoNT/B gene and an Orfx cluster associated with the BoNT/A4 gene. The nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the neurotoxin cluster-specific genes were determined for each neurotoxin cluster and compared among strains. Additionally, the ntnh gene of each strain was compared on both the nucleotide and amino acid levels. The degree of similarity of the sequences of the ntnh genes and corresponding amino acid sequences correlated with the neurotoxin cluster type to which the ntnh gene was assigned.

Clostridium botulinum comprises a heterogeneous group of strains, all of which have the distinctive characteristic of producing botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT). BoNTs are the most potent neurotoxins known to man and are considered a potential weapon for bioterrorism (3). BoNTs are characterized as category A select agents and are considered potential bioterrorism threats (3).

BoNTs can be immunologically distinguished using homologous antitoxins into seven serotypes, designated A to G. Among these serotypes there is considerable genetic variation, as demonstrated by the recognition of at least 47 subtypes identified thus far (15, 28). Previous studies have determined that the BoNT genes of all strains of C. botulinum and neurotoxigenic strains of Clostridium butyricum and Clostridium baratii have a set of genes located upstream of the BoNT gene that are organized as neurotoxin clusters (4, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 23).

Available data indicate that there exist two primary types of neurotoxin clusters: (i) a hemagglutinin (HA) cluster and (ii) an Orfx cluster with genes (orf genes) of unknown function. The HA cluster consists of genes encoding HA17, HA33, HA70, BotR, and NTNH. The Orfx cluster consists of genes encoding Orfx3, Orfx2, Orfx1, P47, P21, and NTNH. The known serotypes associated with HA clusters are BoNT/A1, BoNT/B, BoNT/C, BoNT/D, and BoNT/G, while serotypes BoNT/E, BoNT/F, and BoNT/A2 are associated with Orfx clusters; the E serotype cluster is unique as it lacks p21 (4, 10, 13, 14, 19, 25, 27). However, results from previous studies indicate that different BoNT/A subtypes possess either an HA cluster or an Orfx cluster associated with the expressed bont gene, depending on the subtype and strain (7, 8, 11, 12).

It has been shown that the HA cluster proteins can form toxin complexes of various sizes including LL toxin (∼900 kDa), L toxin (∼500 kDa), and M toxin (∼ 300 kDa), comprised of various combinations of HA proteins, NTNH, and BoNT (∼150 kDa) (17, 18, 23). The biological and structural roles of the complex proteins are not completely characterized, although it is believed that they serve the role of protecting BoNT from digestive enzymes and adverse conditions present in the gastrointestinal tract (23). The function of orfx genes and their role in the neurotoxin cluster are still unknown, but it has been postulated that they perform a function similar to their HA cluster counterparts because the location and orientation of the Orfx and HA cluster genes relative to the BoNT gene in the neurotoxin cluster are analogous (7). A regulatory gene called botR (21, 22) has also been identified in the HA cluster. botR encodes a sigma 70 factor which positively regulates the expression of BoNT and the HA proteins (9). The Orfx cluster has an analogous gene, p21, which appears to be a sigma 70 factor, as determined by amino acid homology BLAST analysis.

BoNT/A is of particular importance and interest since it causes the most severe form of human botulism, is the most significant threat in bioterrorism, and has been increasingly used as a pharmaceutical modality (1, 6). During the past 5 years, a focus of our laboratories has been the study of C. botulinum strains that produce novel BoNT/A subtypes including an A3 strain producing BoNT/A3, an A4 strain that is a bivalent strain producing both BoNT/A4 and BoNT/B (2), and a strain (termed HA− Orfx+ A1) that produces BoNT/A1 with a neurotoxin cluster arrangement normally associated with the BoNT/A2. This paper presents a comprehensive comparison of the individual neurotoxin cluster genes and bont genes among different C. botulinum subtype A strains on both nucleotide and amino acid levels.

In order to study the neurotoxin cluster genes in these subtypes, we have identified and sequenced each of these strains' neurotoxin cluster genes and have compared the results on nucleotide and amino acid levels to the known sequences from ATCC 3502 (a BoNT/A1 producer) (7, 26), Kyoto F (a BoNT/A2 producer) (7), and NCTC 2916 (a BoNT/A1 producer with a unexpressed BoNT/B gene) (10, 16, 24) to determine their genetic relationships and possible genetic lineages. Our laboratory showed that the genes encoding BoNT/A3 and BoNT/A4 are located on large plasmids; this is the first demonstration that genes encoding BoNT/A are present on extrachromosomal elements (20). Prior to our discovery in these strains and the subsequent confirmation of our findings (27), the gene encoding BoNT/A1 was expected to be located on the chromosome by analysis of the genome of C. botulinum ATCC 3502 (26).

Previous studies of BoNT clusters have emphasized the arrangement of the genes and, particularly, the amino acid sequences of the proteins; here, we also address the nucleotide sequence relationships and possible mechanisms of acquisition and rearrangement of the BoNT and neurotoxin cluster genes of the A3 and A4 subtypes. In addition, we describe a novel neurotoxin cluster, HA− Orfx+ A1, in the present study and discuss possible mechanisms of toxin complex acquisition and function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The C. botulinum strain A3 (CDC 40234) was provided by the CDC strain collection and has been shown to be genetically identical to the Loch Maree strain via internal laboratory pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) studies; A4 (657Ba) and HA− Orfx+ A1 (5328A) were provided by the Eric A. Johnson strain collection. Cultures were grown in 10 ml of sterile TPGY medium (50 g/liter trypticase peptone, 5 g/liter Bacto peptone, 4 g/liter d-glucose, 20 g/liter yeast extract, 1 g/liter cysteine-HCl, at pH 7.4) for 2 days at 37°C under anaerobic conditions.

Total genomic DNA isolation.

Total genomic DNA was isolated from C. botulinum by lysozyme and proteinase K treatment as described previously (7). DNA was then diluted to a concentration of 50 ng/μl and used for PCR amplification.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

PCR amplifications were performed using a GeneAmp High Fidelity PCR System (Applied BioSystems). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, annealing for 45 s at 48°C, and extension at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Following amplification, PCR products were isolated using a PureLink PCR purification kit (Invitrogen). Sequencing setups were produced under conditions recommended by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center using an ABI Prism BigDye Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied BioSystems). Primers used for PCR and sequencing are listed in Table 1. PCRs were performed in a staggered manner such that the amplicons produced overlapping products for each of the genes in each neurotoxin cluster. Appropriate primers were then used for sequencing each PCR product. Correct assembly of the contigs was verified by the overlapping sequence data. The toxin genes were sequenced as necessary to confirm the suspected neurotoxin cluster arrangements for each bacterial type. Sequencing analysis was performed at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center, and final sequencing results were analyzed using the Vector NTI Suite program (Invitrogen).

TABLE 1.

Primers used to identify and characterize the clusters present in the various subtypes of C. botulinum studied

| Genea | Primer nameb | Sequence (5′-3′) | Usec |

|---|---|---|---|

| ha70 | HA70F | ATGAATTCATCTATAAAAAAAATTTATAATG | P, S |

| ha70 | HA70R | TTAATTAGTAATATCTATATGCAATCTTATATTATAG | P, S |

| ha33 | HA33F | ATGGAACACTATTCAGTAATCCAAAATTC | P, S |

| ha33 | HA33R | TTATGGGTTACGAATATTCCATTTC | P, S |

| ha17 | HA17F | ATGTCAGTTGAAAGAACTTTTCTACCT | P, S |

| ha17 | HA17R | TTATATTTTTTCAAGTTTGAACATTTGA | P, S |

| HA cluster | HA912 | CAGATGGGTCTATGACACCTAC | S |

| HA cluster | HA1436R | GCACACAACGAGTATTGCC | S |

| HA cluster | HA2114 | CGGTAATAGGAGTAGTGGTTG | S |

| HA cluster | HA2610R | TATCATGGAGATGATAATCAGAAATGG | S |

| HA cluster | HA-46 | CCGAATTCGTATCGGCCTTACAGGAGATGGTAAC | S |

| HA cluster | ORF4183R | GGGTTCTAATCTCTCTAAAGCC | S |

| HA cluster | HA70I1F | AGTGATACTATTGATTTAGCTGATGG | S |

| HA cluster | HA70I1R | TCCTGATGAACCTGCTTCG | S |

| HA cluster | HA70I2F | GCAAGTGGCTGAAGATGGAT | S |

| HA cluster | HA70I2R | GCCGTCAATAGTTTCAGTGACTC | S |

| orfX3 | ORFX3F | ATGCAAACAACAACTTTAAATTGGGATACC | P, S |

| orfX3 | ORFX3R | TTAAGTATTTTGTACTTGTAAAGTTCCTCC | P, S |

| orfX2 | ORFX2F | ATGAATAATTTAAAACCATTTATATATTACGATTGG | P, S |

| orfX2 | ORFX2R | TTATTTGCTGTTAGGCTTATTGTTTTTTTCTAATG | P, S |

| orfX1 | ORFX1F | ATGAATCAAACATTTTCTTTTAATTTTGATGACAC | P, S |

| orfX1 | ORFX1R | TTATGCGATTTGCAATAAATTTTCTTCATTTCC | P, S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX3IF | TAGTTTGCTCCCCCTTGTCA | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX3IR | TCCAACAAGCGAAGATGTTAAA | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX2FI1 | TTCTTTGACCAGTTGACATTGG | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX2RI1 | CGGGAAAGTGGAAAATTCTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX2FI2 | TGTTTTCCGTCATTTTCTCCA | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX2RI2 | TGGAACTTCATGGAACCAAA | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX2FI3 | TTTCCAGGCTTAAGGGATGA | S |

| Orfx cluster | ORFX2RI3 | AGTTGGGAAATGACCACAGG | S |

| Orfx cluster | NT7582R | CTTCACATATAGGCTTATCTGA | S |

| Orfx cluster | KF107R | TGGGAACAAGGAAGAGGTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KF920 | CTGTGGTCATTTCCCAACTATC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KF181R | TGCAAATCGCATAAGGGAGG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KF1283 | AACGTCATTATCTATGGCTTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KF9864R | GCCTTTGTTGCTTCTGCCTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KF11309 | GTAGATGATGGATGGGGAGAAAG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTX3F | TGGGATACCGTATATGCAGTTCC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTX3R | CCATCTAAAAGTTCAAATTGTTCAGG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTX2F2 | CTTCATGGAACCAAAATCACTAATTC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTX2R2 | TTAAGACTGGATGAGATCCTTCACC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTX1F2 | CAAATAATAAAAAACCGAATGAGTTCAC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTX1R2 | CTAAAATTCCATTTTTGGTTATTTTTCC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFORFXR1 | TCCTAGAGCTATAATTACTGACAGGTCTC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFORFXR2 | TGAAGCCTATGGCTATAACTGCC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFORFXR3 | TCTTTGTACTTTGTGGCGAAGG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTBOTRF | CCAAAAATGTTTTAGTATATCATTGTAATTCTC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTBOTRR | ACATTAAAAGATGATAATAAAAAATTTGAAGAC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFBOTRR1 | TCTATATCATTAAAGCAACTATCCTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFBOTRR2 | AGGCTTTAGCTTTTCTAATGC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTP47F | ATAATTGGGAAATTATTAATGGAGGATC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTP47R | CACTTAGATCGACGGTTGTATTTCTTAC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTP47R2 | AGGATTCATCCATTCTATGTCAGATG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTP47R3 | TTAGGATAATAGTAAAGTGCCGCAAC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTNTNHF | GTGGCTCCCAATATCTGGATTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTNTNHR | AATTAGAATCATAAATTCCTCCGTCAG | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTBONTF | GATCCTGTAAATGGTGTTGATATTGC | S |

| Orfx cluster | KFRTBONTR | GTAAAGGTATCTCTTTCTGGAATAACCC | S |

| Orfx cluster | 2916INV3R | GGGATACGGTTTATGCAGTTCC | S |

| Orfx cluster | 2916U1 | CGCTAACGCTTTATTCAAGTC | S |

| Orfx cluster | 2916INV2 | GTTCCACCTAATAGATAAATTCCTTGAAG | S |

| Orfx cluster | 2916ORFX1 | GATTATTTAAAACTGTCTCCACTG | S |

| Orfx cluster | 2916NTNHR | ATCTGTTTTTCTCCCCCTAAC | S |

| Orfx cluster | NT6611R | CTATCTACATTATTCATTGCTATTTGTG | S |

| ntnh-ha | NTNHAF | ATGAATATAAATGACAACTTAAGTATAAATTCC | P, S |

| ntnh-ha | NTNHAR | TTATTTAAATGACCATAAATACAAATACTTTGAC | P, S |

| ntnh-orfx | NTNHA2F | ATGAAAATAAATAATAATTTTAATATTGATTC | P, S |

| ntnh-orfx | NTNHA2R | TTATTTAAATGACCATAAATACAAATATTTTG | P, S |

| ntnh-orfx | NT4961R | GTTCCCATTCCATTTTCTGCATC | P, S |

| ntnh-ha | NTNH-P/A | AGAGAATTCGAGAGATTAGAACCCATATTG | S |

| ntnh-ha | PNTNH/R2 | AGAGGATCCTAAATTTATTTCAACGCACATAC | S |

| ntnh-ha | NT4888 | GGTCCAGGAGCAAACATAGTAGAAAAC | S |

| ntnh-ha | NT5521 | GCTCAATTATCTTTATCAGATAG | S |

| ntnh-orfx | NT6035R | TCTGTATCAATAGGACTATTATCC | S |

| ntnh-orfx | NT6518 | CATCTGATAACTTAGCATTGATGAATC | S |

| ntnh-orfx | NT6611R | CTATCTACATTATTCATTGCTATTTGTG | S |

| ntnh-orfx | NN2913 | CGTTTAAAAGATCAATTATTAATATTTATT | S |

| A toxin gene (LC+HCN) | ALCF | GAGGTGTTAAATATGCCATTTGTTAAT | P, S |

| A toxin gene (LC+HCN) | AHNR | CACCATAATTAAGTGATACTTTCCATC | P, S |

| A toxin gene (HC) | AHNF | TGTATCAAAGTTAATAATTGGGACTTC | P, S |

| A toxin gene (HC) | AHCR | CAATACTCATATCTAGTTATTCTTAAA | P, S |

| B toxin gene (LC+HCN) | B1FINALOF | TGACAATATACCTAAAGCTGCACAT | P, S |

| B toxin gene (LC+HCN) | B2FINALOR | CATTAAGCTTGACCCCATCATATAC | P, S |

| B toxin gene (HC) | B2FINALOF | TCGTTGAAGATTCTGAAGGAAAATA | P, S |

| B toxin gene (HC) | B3FINALOR | TTTTCTTATATAAAATAGGTTTGCTGAG | P, S |

| A toxin gene | ALCR | ATCATTAGTAAAATTATCTTCTGAAGC | S |

| A toxin gene | AHCF | AAT GCTATTGTATATAATAGTATGTAT | S |

| A toxin gene | CHIMERIC R | TCT TGAGCACGAAGATAATGGAAG | S |

| A toxin gene | ALC2F | TACCATTTTGGGGTGGAG T | S |

| A toxin gene | AHCN BACKUPF | AAAGCTACGGAGGCAGCTATG | S |

| A toxin gene | AHCN BACKUPR | GCCTTTGTTGCTTCTGCTTG | S |

| A toxin gene | AHCC BACKUPF | AAACAGATGGATTTTTGTAACTATCA | S |

| A toxin gene | AHCC BACKUPR | ACGCTACCTCTAGGCCCTTT | S |

| A toxin gene | ALCF | GAGGTGTTAAATATGCCATTTGTTAAT | S |

| B toxin gene | B1FINALOR | CTTATATACAGCCAAATGCTCCTT G | S |

| B toxin gene | B1FINALIF | CCATTGGGTGAAAAGTTATTAGAGA | S |

| B toxin gene | B1FINALIR | TAAATATACTTGCGCCTTTGTTTTC | S |

| B toxin gene | B2FINALIF | GGTTGGGTGAAACAGATAGTAGATG | S |

| B toxin gene | B2FINALIR | TCAATCCATTTTTCCACTCTTTTAG | S |

| B toxin gene | B3FINALOF | ACCATTTGATCTTTCAACGTATTCT | S |

| B toxin gene | B3FINALIF | TATGAAAAATAATTCAGGGCTGGAAA | S |

| B toxin gene | B3FINALIR | ATACATTAAAGGATTTCCCCAAAAA | S |

The HA cluster includes ha17, ha33, ha70, and botR genes; the Orfx cluster includes orfx1, orfx2, orfx3, p47, and p21 genes; ntnh-ha is the ntnh gene from the HA cluster; ntnh-orfx is the ntnh gene from the Orfx cluster. A toxin gene (LC+HCN), light chain and heavy chain N terminus of BoNT/A gene; A toxin (HC), heavy chain from BoNT/A gene; B toxin gene (LC+HCN), light chain and heavy chain of N terminus of the BoNT/B gene; B toxin gene (HC), heavy chain of the BoNT/B gene; A toxin gene, BoNT/A gene; B toxin gene, BoNT/B gene.

R, reverse; F, forward; I, internal; O, outer.

S, sequencing; P, PCR.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences for the various neurotoxin clusters were determined and deposited in the GenBank database under the following accession numbers: 657Ba BoNT/B HA cluster, accession number EU341304; 657Ba BoNT/A4 Orfx cluster, EU341307; CDC 40234 BoNT/A3 Orfx cluster, EU341306; and HA− Orfx+ A1 BoNT/A1 Orfx cluster, EU341305.

RESULTS

Identification of the neurotoxin cluster genes and their arrangements in strains A3, A4 and HA− Orfx+ A1.

PCR and sequencing reactions were performed on the neurotoxin cluster genes of the A3, A4 and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains, and the results were compiled using the VectorNTI Suite program. Strain A3 produces BoNT/A3 and was identified as containing only one neurotoxin cluster, an Orfx cluster similar to that in A2 (8). A4 contained two sets of neurotoxin cluster genes that were similar to what had been found in many A(B) strains including NCTC 2916 (16), in which the HA cluster is associated with a silent (unexpressed) BoNT/B gene, and the Orfx cluster is associated with the BoNT/A gene. HA− Orfx+ A1 contained an Orfx cluster that was similar to A2 but still produced only BoNT/A1 (Fig. 1). The results showed that C. botulinum subtype A strains have relatively high variation in the BoNT/A gene and its associated genes within the toxin complex.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the six known cluster arrangements for C. botulinum strains producing BoNT/A neurotoxin. Gene location and direction are indicated by arrows with gene nomenclature given beneath each one. Strain identifications are given to the right of the series of genes in each cluster.

Comparison of ha genes.

For the A subtype strains studied, only A4 possessed an HA cluster which was associated with a BoNT/B gene. This neurotoxin cluster was analogous to the HA cluster associated with the BoNT/A1 gene from A1 and the HA cluster associated with the silent BoNT/B gene from NCTC 2916 (Fig. 1). When the A4 HA cluster and the A1 HA cluster were compared at the nucleotide level, the ha70, ha33, and ha17 genes showed 98.5%, 98.7%, and 100% identity, respectively (Table 2). On the amino acid level, the HA70 proteins from these two neurotoxin clusters had 97.4% similarity and 97.1% identity, the HA33 proteins had 97.3% similarity and identity, and HA17 had 100% similarity and identity (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide identity among the genes of the C. botulinum HA clustera

| Strain | Nucleotide identity (%)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ha70

|

ha33

|

ha17

|

botR

|

|||||

| A4-B | NC-B | A4-B | NC-B | A4-B | NC-B | A4-B | NC-B | |

| A1 | 98.5 | 98.2 | 98.7 | 99.3 | 100 | 100 | 98.5 | 98.7 |

| A4-B | 99.2 | 99.2 | 100 | 99.4 | ||||

Strains: A1, strain carrying the BoNT/A1 gene (NCBI accession no. AF461539); A4-B, strain carrying the BoNT/B gene with the corresponding HA cluster; NC-B, NCTC 2916 carrying the BoNT/B gene with the corresponding HA cluster.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid similarity and identity for the proteins of the C. botulinum HA clustera

| Strain | Amino acid similarity and identity (%)b

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA70

|

HA33

|

HA17

|

BotR

|

|||||

| A4-B | NC-B | A4-B | NC-B | A4-B | NC-B | A4-B | NC-B | |

| A1 | 97.4, 97.1 | 97.1, 96.8 | 97.3, 97.3 | 99.0, 98.6 | 100, 100 | 100, 100 | 97.8, 97.8 | 98.3, 98.3 |

| A4-B | 98.7, 98.7 | 98.3, 98.3 | 100, 100 | 99.4, 99.4 | ||||

For strains, see Table 2, footnote a.

Values are raw numbers and are given in respective order (similarity, identity).

High degrees of identities in their genes and proteins were observed between the A4 HA and NCTC 2916 HA clusters. At the nucleotide level, the ha70 and ha33 genes were 99.2% identical, and the ha17 genes were 100% identical (Table 2). On the amino acid level the HA70 proteins showed 98.7% similarity and identity, the HA33 proteins had 98.3% similarity and identity, and HA17 proteins had 100% similarity and identity (Table 3). Based on these results, the A4 HA cluster associated with the BoNT/B gene was most similar to the HA cluster in the NCTC 2916 strain, which is also associated with its unexpressed BoNT/B gene.

Comparison of orfx and p47 genes.

Analysis of the Orfx cluster genes of the A3, A4 and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains gave more diverse results. Comparisons of the nucleotide sequences of the orfx3 genes demonstrated that the highest degree of similarity was between the HA− Orfx+ A1 and the NCTC 2916 strains. orfx3 in strain A3 had the highest degree of divergence with 91.9% identity compared to the gene in HA− Orfx+ A1 (Table 4). On the amino acid level, the relationships among the various strains were consistent with the nucleotide relationship except that the difference between A3 and HA− Orfx+ A1 was less pronounced as many of the nucleotide alterations resulted in conserved amino acid changes (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Nucleotide identity (%) between the genes of the C. botulinum Orfx clustera

| Strain | Nucleotide identity (%)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

orfx3

|

orfx2

|

orfx1

|

p47

|

p21

|

||||||||||||||||

| A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | |

| A2 | 95.9 | 97.9 | 94.4 | 94.8 | 97.2 | 85.9 | 97.9 | 98.0 | 97.4 | 90.6 | 94.4 | 93.9 | 96.4 | 80.4 | 100 | 85.6 | 93.5 | 95.1 | 94.4 | 94.6 |

| A3 | 97.5 | 91.9 | 91.9 | 85.4 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 90.4 | 92.3 | 91.8 | 81.8 | 96.4 | 86.8 | 96.8 | 92.5 | 93.1 | |||||

| A4-A | 94.0 | 93.9 | 86.3 | 86.3 | 88.7 | 88.3 | 80.4 | 81.3 | 94.2 | 94.8 | ||||||||||

| HA− Orfx+ A1 | 99.7 | 99.9 | 99.5 | 85.6 | 99.4 | |||||||||||||||

Strains: A2, strain carrying the BoNT/A2 gene (NCBI accession no. AY953275); A3, strain carrying the BoNT/A3 gene (DQ185900); A4-A, strain carrying the BoNT/A4 gene (DQ185901) and corresponding Orfx cluster; HA− Orfx+ A1, strain carrying the BoNT/A1 gene, with an Orfx style cluster without the presence of a silent or expressed BoNT/B gene; NC-A, NCTC 2916 with the A toxin gene and corresponding HA cluster.

TABLE 5.

Amino acid similarity and identity for the proteins of the C. botulinum Orfx clustera

| Strain | Amino acid similarity and identity (%)b

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orfx3

|

Orfx2

|

Orfx1

|

p47

|

p21

|

||||||||||||||||

| A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | A3 | A4-A | HA− Orfx+ A1 | NC-A | |

| A2 | 96.2, 94.7 | 97.5, 97.5 | 95.2, 93.9 | 95.9, 94.7 | 96.4, 95.3 | 85.6, 78.3 | 97.6, 96.8 | 97.6, 96.8 | 97.9, 97.2 | 91.5, 87.3 | 91.5, 90.1 | 90.8, 89.4 | 97.1, 95.0 | 81.2, 73.8 | 100, 100 | 85.1, 79.3 | 92.9, 91.3 | 93.8, 92.1 | 93.3, 92.7 | 94.4, 93.8 |

| A3 | 98.1, 96.6 | 93.6, 90.9 | 93.6, 90.9 | 85.0, 78.3 | 96.3, 95.7 | 96.4, 95.7 | 91.5, 88.0 | 90.8, 88.7 | 99.3, 99.3 | 82.7, 75.2 | 97.1, 95.0 | 85.3, 80.3 | 92.4, 91.3 | 87.5, 85.3 | 88.6, 86.4 | |||||

| A4-A | 94.5, 93.3 | 95.4, 93.7 | 85.9, 79.1 | 85.9, 79.1 | 89.4, 85.2 | 88.7, 84.5 | 81.2, 73.8 | 81.2, 74.5 | 92.1, 91.0 | 92.7, 91.6 | ||||||||||

| HA− Orfx+ A1 | 99.2, 99.2 | 99.7, 99.7 | 99.3, 99.3 | 85.1, 79.3 | 98.9, 98.9 | |||||||||||||||

For strains, see Table 4, footnote a.

Values are raw numbers and are given in respective order (similarity, identity).

For orfx2, the highest degree of similarity was observed between the HA− Orfx+ A1 and NCTC 2916 strains, which was similar to that found for orfx3. The orfx2 gene of A4 was most divergent from the other strains, with only 85.9% identity compared to the A2 strain (Table 4). However, the difference in nucleotide sequences of orfx2 between A4 and A2 was more pronounced on the amino acid level as they were only 85.6% similar and 78.3% identical (Table 5). A similar trend to that observed in orfx3 was observed in orfx2 as HA− Orfx+ A1 and NCTC 2916 were 99.7% identical to each other on the amino acid level.

Comparison of the orfx1 genes gave a different order of relatedness, whereby the A3 strain was most similar to A2, followed by HA− Orfx+ A1, and then A4 (Table 4). At the nucleotide level, the orfx1 gene from A3 and HA− Orfx+ A1 were closely related to that of A2, having 97.4% and 94.4% identity, respectively, while having 92.3% identity to each other (Table 4). However, at the amino acid level, the differences between the A3 and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains compared to A2 were substantial. While A3 was 97.9% and 97.2% similar and identical to A2, HA− Orfx+ A1 showed 91.5% similarity and 90.1% identity to A2, lending slightly more identity than A4 (Table 5).

The relatedness of the p47 genes was interesting as it is the only gene of the Orfx cluster in which HA− Orfx+ A1 strain had 100% nucleotide identity with p47 of A2 (Kyoto F). Based on nucleotide identity, the order of relatedness to A2 was HA− Orfx+ A1, A3, and then A4 with only 80.4% identity (Table 4). The similarities on the amino acid level followed the same pattern as those seen on the nucleotide level (Table 5).

Comparison of the regulatory genes in the HA and Orfx neurotoxin clusters.

Both the HA and Orfx clusters contained a regulatory gene designated botR or p21 based on substantial similarity, but the gene was most homologous to those of the same neurotoxin cluster type. In addition, the two genes were in the opposite orientation to each other within their specific neurotoxin clusters. For botR in the HA cluster, the A4 strain exhibited 98.5% nucleotide identity and 97.8% amino acid similarity and identity to A1 (Tables 2, 3). Compared to the NCTC 2916 HA cluster, A4 demonstrated 99.4% identity on the nucleotide level and was 99.4% identical and similar on the amino acid level.

For the Orfx cluster, p21 in A2 was most similar to p21 in A4 with 95.1% nucleotide identity, similar to HA− Orfx+ A1 with 94.4% identity, and finally similar to A3 with 93.5% identity (Table 4). The amino acid order similarities followed a parallel pattern except that HA− Orfx+ A1 had a slightly higher amino acid identity compared to A2 than A4, indicating that some of the nucleotide substitutions were silent mutations (Table 5).

Comparison of the ntnh genes.

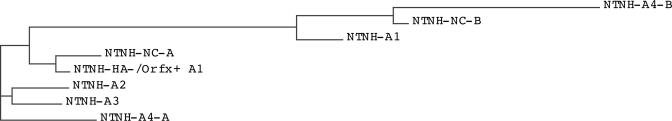

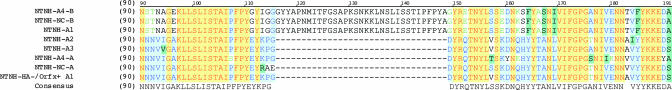

ntnh is the only gene other than bont that is present in both the HA and Orfx clusters. On the nucleotide level, the ntnh genes showed closest homology within similar neurotoxin clusters, and ntnh in the A1 HA cluster had a high level of homology compared to the ntnh genes in the HA clusters of the A4 and NCTC 2916 strains. The ntnh gene in the Orfx cluster of A2 had high homology to the ntnh genes in the Orfx clusters of A3 and HA− Orfx+ A1, as well as the Orfx cluster associated with the BoNT/A in A4 and NCTC 2916 (Table 6). The same trend was observed on the amino acid level (Table 6 and Fig. 2). An insertion of 99 nucleotides in the ntnh genes of the HA cluster was detected, which gave a gene of 3,821 bp in length compared to the 3,722 bp ntnh in the Orfx cluster. As a result, the NTNH in the HA cluster contains an additional 33 amino acids starting at position 113 (Fig. 3).

TABLE 6.

Comparison of NTNH on the nucleotide and amino acid levels among C. botulinum type A strainsa

| Strain | Nucleotide identity or amino acid similarity and identity by strain (%)b

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2

|

A3

|

A4-A

|

A4-B

|

HA− Orfx+ A1

|

NC-A

|

NC-B

|

||||||||

| Nt | AA | Nt | AA | Nt | AA | Nt | AA | Nt | AA | Nt | AA | Nt | AA | |

| A1 | 82.7 | 81.8, 76.3 | 82.3 | 81.7, 76.7 | 82.0 | 80.8, 75.3 | 88.2 | 87.1, 82.8 | 83.7 | 83.3, 77.9 | 84.0 | 83.2, 78.2 | 93.2 | 93.2, 90.0 |

| A2 | 95.9 | 95.9, 94.4 | 94.5 | 93.0, 91.0 | 73.2 | 71.7, 62.7 | 95.6 | 95.3, 93.6 | 93.9 | 93.6, 91.0 | 79.8 | 79.8, 72.4 | ||

| A3 | 95.4 | 93.6, 91.8 | 73.8 | 71.8, 62.9 | 93.2 | 94.9, 93.0 | 93.4 | 93.4, 90.9 | 79.6 | 79.4, 72.2 | ||||

| A4-A | 73.1 | 71.0, 62.0 | 94.4 | 92.7, 91.0 | 93.1 | 91.4, 88.8 | 79.6 | 78.5, 71.3 | ||||||

| A4-B | 74.0 | 72.8, 64.4 | 74.9 | 73.4, 65.7 | 91.9 | 90.6, 88.4 | ||||||||

| HA− Orfx+ A1 | 97.7 | 97.8, 96.8 | 81.6 | 81.8, 75.2 | ||||||||||

| NC-A | 82.7 | 71.0, 62.0 | ||||||||||||

FIG. 2.

Graphical representation of degree of relatedness between the amino acid sequences of the NTNH proteins found in various BoNT/A producing bacteria (drawn to scale). The degree of such relatedness depends on different types of clusters. NTNHs from the HA clusters of different strains are closely related; so are those from Orfx clusters of different strains. However, the degree of relatedness among NTNHs between the two cluster types is lower than that within the same cluster type. NTNH-A1, NTNH in the HA cluster with BoNT/A1; NTNH-A2, NTNH in the Orfx cluster with BoNT/A2; NTNH-A3, NTNH in the Orfx cluster with BoNT/A3; NTNH-A4-A, NTNH in the Orfx cluster with BoNT/A4; NTNH-A4-B, NTNH in the HA cluster with BoNT/B; NTNH-ha-/orfx+ A1, NTNH in the Orfx cluster with BoNT/A1 in the HA− Orfx+ A1 strain; NTNH-NC-A, NTNH in the Orfx cluster with BoNT/A1 in NCTC 2916 strain; NTNH-NC-B, NTNH in the HA cluster with the silent BoNT/B in NCTC 2916.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of a region of the amino acid sequences of the NTNH genes associated with BoNT in known BoNT/A-producing strains using AlignX software. This figure shows that NTNHs in the Orfx cluster have amino acid deletions compared with those in the HA cluster. The numbers above the alignment indicate the locations of the amino acids of NTNHs in the NTNH genes. All sequences start at the 96th amino acid. Red letters in yellow blocks indicate conserved amino acids, blue letters in light blue blocks indicated conserved amino acids, green letters in white blocks indicate that the amino acids are changed but retain similar properties compared to the amino acids in the other samples, black letters in white blocks indicate distinctness compared to the other samples, and dashes indicate deletions.

Comparison of the bont genes.

The nucleotide and amino acid homologies of the BoNT/A genes in C. botulinum strains examined in this study are shown in Table 7. Analysis of the bont gene sequences demonstrated significantly divergent relationships among the various strains compared to the other neurotoxin cluster genes such as the BoNT/A1 gene. The BoNT/A gene in HA− Orfx+ A1 had only 5 nucleotide differences compared to the BoNT/A1 gene over its 3,891-nucleotide length (Table 7). This result was unexpected since these two genes had distinct gene neurotoxin cluster contents, with the A1 strain having an HA cluster while HA− Orfx+ A1 had an Orfx cluster. Additionally, it was found that most of the differences in the HA− Orfx+ A1 BoNT occurred in the heavy chain, with the light chains of the two strains being 99.8% identical.

TABLE 7.

Comparison of BoNT on the nucleotide and amino acid levels among C. botulinum type A strainsa

| Strain | Nucleotide identity or amino acid similarity and identity by strain (%)b

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2

|

A3

|

A4-A

|

HA− Orfx+ A1

|

|||||||||||||

| Nt | AA

|

Nt | AA

|

Nt | AA

|

Nt | AA

|

|||||||||

| WT | LC | HC | WT | LC | HC | WT | LC | HC | WT | LC | HC | |||||

| A1 | 94.7 | 93.0, 89.9 | 96.9, 95.1 | 90.9, 87.1 | 91.9 | 88.4, 84.3 | 84.6, 81.0 | 90.3, 86.0 | 94.2 | 91.5, 89.0 | 90.6, 88.6 | 92.0, 89.3 | 99.9 | 99.8, 99.7 | 100, 100 | 99.6, 99.5 |

| A2 | 96.3 | 94.7, 92.9 | 86.8, 83.9 | 98.8, 97.6 | 93.5 | 91.7, 88.1 | 89.7, 86.4 | 92.7, 89.0 | 94.6 | 92.8, 89.7 | 96.9, 95.1 | 90.7, 86.8 | ||||

| A3 | 91.4 | 87.9, 84.1 | 80.1, 76.3 | 92.0, 88.2 | 91.8 | 88.3, 84.2 | 84.6, 81.0 | 90.2, 85.7 | ||||||||

| A4-A | 94.2 | 91.6, 89.0 | 90.6, 88.6 | 92.1, 89.3 | ||||||||||||

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that there is substantial sequence variation among the HA and Orfx cluster genes and bont in the A3, A4, and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains. At least two lines of evidence suggest that the neurotoxin cluster arrangements derived from several recombination events. First, bont nucleotide sequences of A3, A4, and HA− Orfx+ A1 were dissimilar, but their respective neurotoxin cluster genes were highly similar; and in those strains with similar bont genes, highly divergent neurotoxin clusters were observed. Second, the ntnh genes were most similar to other ntnh genes of the same neurotoxin cluster. Specifically, the ntnh genes associated with HA clusters were more similar to each other than to the ntnh genes associated with the Orfx clusters.

The notion that several unique recombination events led to the neurotoxin cluster organization observed in the strains analyzed is also supported by MLST experiments performed in our laboratory for strain comparison and delineation (M. Jacobson et al., unpublished data). The A4 and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains differed in only one of the seven gene alleles examined. However, the A2 and A3 strains were highly dissimilar as they did not have any allele sequences in common with any of the other C. botulinum strains or with each other. A(B) strains demonstrated a high level of heterogeneity since multiple MLST patterns were observed. Given the lack of evidence for a common clonal relationship among strains containing similar (HA or Orfx) neurotoxin clusters, it is unlikely that the neurotoxin clusters are the result of some shared ancestry among the isolates examined; although there is a high degree of similarity among neurotoxin clusters, the strains themselves demonstrated a high degree of genetic variability. A more plausible explanation for the nucleotide sequence similarity among the genes of similar (HA or Orfx) neurotoxin clusters is that recent recombination events have occurred in the history of such strains, leading to the creation of the BoNT neurotoxin clusters within the snapshot in time observed today.

The ntnh gene is the only gene other than bont present in all neurotoxin clusters from C. botulinum, including both HA and Orfx clusters. NTNHs from HA clusters of different strains are closely related, as are those from Orfx clusters of different strains. However, the ntnh genes were most similar to other ntnh genes of the same neurotoxin cluster. Specifically, the ntnh genes associated with HA clusters were more similar to each other than to the ntnh genes associated with the Orfx clusters. One possible explanation for this difference is that some or all of the ntnh gene was transferred along with the HA or Orfx cluster genes via a recombination event. This hypothesis is supported by the presence of an insertion of 99 nucleotides in the ntnh genes of all the HA clusters examined. This insertion translates to an additional 33 amino acids starting at position 113 in the NTNH of the HA cluster (Fig. 3).

Analysis of the orfx3 gene demonstrated that genes from the HA− Orfx+ A1 and NCTC 2916 strains were most similar to each other and that those from the A2, A4, and A3 were more divergent. A similar trend was observed for the orfx2 and orfx1 genes, with the HA− Orfx+ A1 and NCTC 2916 strains being highly similar while A2 and A3 were similar to each other, and A4 was the most divergent of all the strains tested. This trend was somewhat expected since both the NCTC 2916 and HA− Orfx+ A1 strains exhibited a BoNT/A1 gene associated with an Orfx cluster. However, the two strains are distinct. The NCTC 2916 strain exhibits an unexpressed BoNT/B gene with an HA cluster but the HA− Orfx+ A1 strain completely lacks this neurotoxin cluster and bont/b. Therefore, it is possible that the two strains gained their respective BoNT/A-associated neurotoxin clusters from a similar recombination event separately from the insertion of the BoNT/B neurotoxin cluster in NCTC 2916. This view is further supported when the p21 and ntnh genes of the Orfx clusters are compared as the HA− Orfx+ A1 and NCTC 2916 strains showed the highest degree of similarity for the strains tested for the two genes.

The p47 gene is particularly interesting as it is the only one of the Orfx cluster-specific genes that is in the same orientation and likely to be cotranscribed (8) with ntnh and bont. Comparison of the p47 nucleotide and amino acid sequences indicated that the HA− Orfx+ A1 and A2 strains were most similar, which is not consistent with the results observed with the other genes. Additionally, it was observed that p47 genes in the A4 and NCTC 2916 strains were highly divergent from other strains and each other. The specific role of the p47 gene is unknown, but it may either serve as a regulatory gene or encode a component of the toxin complex. Further studies will be required to elucidate its function and the significance of its genetic lineages within the subtypes.

A clearer relationship was observed when the HA clusters were compared as the A4 and NCTC 2916 BoNT/B-associated neurotoxin clusters demonstrated high levels of similarity for all of the genes tested. This further supports the theory that the neurotoxin clusters arose from genetic events distinct from the evolution of the clostridia since, as mentioned above, the NCTC 2916 and A4 bacteria did not demonstrate the same degree of relatedness when they were compared using an MLST procedure as they did when their neurotoxin cluster genes were compared. Based on these observations and the fact that the BoNTs of each strain are so different, it is highly likely that these neurotoxin clusters also arose from recombination events distinct from those that produced the BoNT genes.

Therefore, the bont gene and its associated neurotoxin cluster genes appear to have been acquired and evolved distinctly in the C. botulinum type A strains examined. The origin and mechanisms of acquisition of the toxin gene neurotoxin clusters, as well as their conservation of gene arrangement and sequence homology, are intriguing. It is likely that their acquisition took place through horizontal gene transfer by plasmid- or phage-mediated gene transfer. Notably, the A3 and A4 gene clusters reside on plasmids; however, the mobility of these plasmids among clostridial strains has not been examined. It appears likely that the acquisition of the neurotoxin clusters occurred as a series of evolutionary events more recent than the divergence of the neurotoxigenic clostridia from a common precursor organism since the neurotoxin cluster genes show relatively high homology. The neurotoxin cluster genes have been shown to be dispensable since the Johnson laboratory has isolated strains that have deletions of the entire A1 neurotoxin cluster and yet have the same physiology and growth properties as the toxigenic parents, to the best of our knowledge based on comparative studies. Lastly, the origin of the bont and neurotoxin cluster genes is a very intriguing mystery. Due to the polyprotein properties of the proteins in the complex and their proteolytic maturation, it has been postulated that the genes may have originated from a mammalian virus, perhaps of a neurotropic source (5, 18).

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the NIH/NIAID Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research Program. We acknowledge membership within and support from the Pacific Southwest Regional Center of Excellence (grant U54 AI065359). Additional funding for this project was provided by the NIAID under cooperative agreement U01 AI056493.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki, K. R. 2003. Pharmacology and immunology of botulinum toxin type A. Clin. Dermatol. 21:476-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arndt, J. W., M. J. Jacobson, E. E. Abola, C. M. Forsyth, W. H. Tepp, J. D. Marks, E. A. Johnson, and R. C. Stevens. 2006. A structural perspective of the sequence variability within botulinum neurotoxin subtypes A1-A4. J. Mol. Biol. 362:733-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnon, S. S., R. Schechter, T. V. Inglesby, D. A. Henderson, J. G. Bartlett, M. S. Ascher, E. Eitzen, A. D. Fine, J. Hauer, M. Layton, S. Lillibridge, M. T. Osterholm, T. O'Toole, G. Parker, T. M. Perl, P. K. Russell, D. L. Swerdlow, K. Tonat, and Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. 2001. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 285:1059-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandari, M., K. D. Campbell, M. D. Collins, and A. K. East. 1997. Molecular characterization of the clusters of genes encoding the botulinum neurotoxin complex in Clostridium botulinum (Clostridium argentinense) type G and nonproteolytic Clostridium botulinum type B. Curr. Microbiol. 35:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DasGupta, B. R. 2006. Botulinum neurotoxins: perspective on their existence and as polyproteins harboring viral proteases. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 52:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado, M. R. 2003. Botulinum neurotoxin type A. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 11:291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dineen, S. S., M. Bradshaw, and E. A. Johnson. 2003. Neurotoxin gene clusters in Clostridium botulinum type A strains: sequence comparison and evolutionary implications. Curr. Microbiol. 46:345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dineen, S. S., M. Bradshaw, C. E. Karasek, and E. A. Johnson. 2004. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the type A2 neurotoxin gene cluster in Clostridium botulinum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 235:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupuy, B., S. Raffestin, S. Matamouros, N. Mani, M. R. Popoff, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2006. Regulation of toxin and bacteriocin gene expression in Clostridium by interchangeable RNA polymerase sigma factors. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1044-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.East, A. K., M. Bhandari, J. M. Stacey, K. D. Campbell, and M. D. Collins. 1996. Organization and phylogenetic interrelationships of genes encoding components of the botulinum toxin complex in proteolytic Clostridium botulinum types A, B, and F: evidence of chimeric sequences in the gene encoding the nontoxic nonhemagglutinin component. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:1105-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franciosa, G., F. Floridi, A. Maugliani, and P. Aureli. 2004. Differentiation of the gene clusters encoding botulinum neurotoxin type A complexes in Clostridium botulinum type A, Ab, and A(B) strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7192-7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franciosa, G., A. Maugliani, F. Floridi, and P. Aureli. 2006. A novel type A2 neurotoxin gene cluster in Clostridium botulinum strain Mascarpone. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 261:88-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser, D., M. W. Eklund, P. Boquet, and M. R. Popoff. 1994. Organization of the botulinum neurotoxin C1 gene and its associated non-toxic protein genes in Clostridium botulinum C 468. Mol. Gen. Genet. 243:631-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser, D., M. Gibert, J. C. Marvaud, M. W. Eklund, and M. R. Popoff. 1995. Botulinal neurotoxin C1 complex genes, clostridial neurotoxin homology and genetic transfer in Clostridium botulinum. Toxicon 33:515-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill, K. K., T. J. Smith, C. H. Helma, L. O. Ticknor, B. T. Foley, R. T. Svensson, J. L. Brown, E. A. Johnson, L. A. Smith, R. T. Okinaka, P. J. Jackson, and J. D. Marks. 2007. Genetic diversity among botulinum neurotoxin-producing clostridial strains. J. Bacteriol. 189:818-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutson, R. A., Y. Zhou, M. D. Collins, E. A. Johnson, C. L. Hatheway, and H. Sugiyama. 1996. Genetic characterization of Clostridium botulinum type A containing silent type B neurotoxin gene sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 271:10786-10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue, K., Y. Fujinaga, T. Watanabe, T. Ohyama, K. Takeshi, K. Moriishi, H. Nakajima, K. Inoue, and K. Oguma. 1996. Molecular composition of Clostridium botulinum type A progenitor toxins. Infect. Immun. 64:1589-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson E. A., and M. Bradshaw. 2001. Clostridium botulinum and its neurotoxins: a metabolic and cellular perspective. Toxicon 39:1703-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubota, T., N. Yonekura, Y. Hariya, E. Isogai, H. Isogai, K. Amano, and N. Fujii. 1998. Gene arrangement in the upstream region of Clostridium botulinum type E and Clostridium butyricum BL6340 progenitor toxin genes is different from that of other types. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 158:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall, K. M., M. Bradshaw, S. Pellett, and E. A. Johnson. 2007. Plasmid encoded neurotoxin genes in Clostridium botulinum serotype A subtypes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361:49-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marvaud, J. C., U. Eisel, T. Binz, H. Niemann, and M. R. Popoff. 1998. TetR is a positive regulator of the tetanus toxin gene in Clostridium tetani and is homologous to BotR. Infect. Immun. 66:5698-5702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marvaud, J. C., M. Gibert, K. Inoue, Y. Fujinaga, K. Oguma, and M. R. Popoff. 1998. botR/A is a positive regulator of botulinum neurotoxin and associated non-toxin protein genes in Clostridium botulinum A. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1009-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oguma, K., Y. Fujinaga, and K. Inoue. 1995. Structure and function of Clostridium botulinum toxins. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez Jovita, M., M. D. Collins, and A. K. East. 1998. Gene organization and sequence determination of the two botulinum neurotoxin gene clusters in Clostridium botulinum type A(B) strain NCTC 2916. Curr. Microbiol. 36:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos-Buelga, J. A., M. D. Collins, and A. K. East. 1998. Characterization of the genes encoding the botulinum neurotoxin complex in a strain of Clostridium botulinum producing type B and F neurotoxins. Curr. Microbiol. 37:312-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebaihia, M., M. W. Peck, N. P. Minton, N. R. Thomson, M. T. Holden, W. J. Mitchell, A. T. Carter, S. D. Bentley, D. R. Mason, L. Crossman, C. J. Paul, A. Ivens, M. H. Wells-Bennik, I. J. Davis, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, C. Churcher, M. A. Quail, T. Chillingworth, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, I. Goodhead, Z. Hance, K. Jagels, N. Larke, M. Maddison, S. Moule, K. Mungall, H. Norbertczak, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. Sanders, M. Simmonds, B. White, S. Whithead, and J. Parkhill. 2007. Genome sequence of a proteolytic (group I) Clostridium botulinum strain Hall A and comparative analysis of the clostridial genomes. Genome Res. 17:1082-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith, T. J., K. K. Hill, B. T. Foley, J. C. Detter, A. C. Munk, D. C. Bruce, N. A. Doggett, L. A. Smith, J. D. Marks, G. Xie, and T. S. Brettin. 2007. Analysis of the neurotoxin complex genes in Clostridium botulinum A1-A4 and B1 strains: BoNT/A3, /Ba4 and /B1 clusters are located on plasmids. PLoS One 2:e1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, T. J., J. Lou, I. N. Geren, C. M. Forsyth, R. Tsai, S. L. Laporte, W. H. Tepp, M. Bradshaw, E. A. Johnson, L. A. Smith, and J. D. Marks. 2005. Sequence variation within botulinum neurotoxin serotypes impacts antibody binding and neutralization. Infect. Immun. 73:5450-5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]