Abstract

Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 is a soil-residing actinomycete with many favorable metabolic capabilities that make it an ideal candidate for the bioremediation of contaminated soils. Arguably the most basic requirement for life is water, yet some nonsporulating bacteria, like RHA1, can survive lengthy droughts. Here we report the first transcriptomic analysis of a gram-positive bacterium during desiccation. Filtered RHA1 cells incubated at either low relative humidity (20%), as an air-drying treatment, or high relative humidity (100%), as a control, were transcriptionally profiled over a comprehensive time series. Also, the morphology of RHA1 cells was characterized by cryofixation scanning electron microscopy during each treatment. Desiccation resulted in a transcriptional response of approximately 8 times more differentially regulated genes than in the control (819 versus 106 genes, respectively). Genes that were differentially expressed during only the desiccation treatment primarily had expression profiles that were maximally up-regulated upon complete drying of the cells. The microarray expression ratios for some of the highly up-regulated genes were verified by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR. These genes included dps1, encoding an oxidative stress protection protein which has not previously been directly associated with desiccation, and the two genes encoding sigma factors SigF1 and SigF3, possibly involved in the regulatory response to desiccation. RHA1 cells also induced the biosynthetic pathway for the compatible solute ectoine. These desiccation-specific responses represent the best candidates for important mechanisms of desiccation resistance in RHA1.

Fluctuation in water availability is a fundamental stress challenging soil-residing microorganisms, and desiccation tolerance is a key adaptation of many such organisms. The structural integrity and proper functioning of many proteins and other cellular macromolecules depend upon interactions with water molecules. The mechanisms by which microorganisms adapt to water limitation have been best studied in cyanobacteria. Many cyanobacteria mitigate water loss by synthesizing extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) to create a barrier between themselves and the dry environment (31). The second main strategy employed by cyanobacteria for retaining water during air drying is to increase their intracellular solute concentrations to equilibrate them with those of their increasingly hypertonic surroundings (41). The molecules either imported or synthesized for this purpose are referred to as compatible solutes because, even at high concentrations, they permit cellular machinery to function (32). In a microarray study of a desiccated cyanobacterial species, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120, the importance of compatible solute production as a major water stress response was identified (21). Other, concurrent responses included the up-regulation of genes associated with protein stabilization (heat shock and chaperone proteins) and with countering oxidative threats (probable manganese catalase), the latter being consistent with findings of increased reactive oxygen species in desiccated cells (9, 25).

Besides cyanobacteria, actinomycetes, including nonsporulating Rhodococcus spp. (33), are also known to have high desiccation tolerance (11). Actinomycetes are an abundant bacterial group in soil, with a critical role in the decomposition of organic matter. Of particular environmental interest is Rhodococcus jostii strain RHA1, because it can degrade a broad range of organic compounds, both natural and xenobiotic, such as gasoline components and highly chlorinated polychlorinated biphenyls (14, 45). Understanding the factors contributing to the desiccation resistance of RHA1 will be valuable to our basic knowledge of soil processes and to its application to contaminated soils subject to droughts. The morphological and physiological changes induced by water stress have been observed for Rhodococcus opacus PD630, a species closely related to RHA1 (16). Alvarez and coworkers assayed a range of known desiccation responses and found that PD630 produced an EPS slime and three osmolytes—trehalose, ectoine, and hydroxyectoine (2). Since the air-dried cells were also starving, respiratory activity was greatly reduced and the cells utilized fatty acid reserves for energy and biosynthetic precursors (2). Other survival adaptations of this strain included cell wall modifications, reductive division, and cell aggregation (2). A remaining question from many bacterial desiccation studies is whether the responses that are a direct consequence of reduced water availability can be distinguished from those induced by other stresses associated with desiccation.

Work has begun in identifying the various strategies used by actinomycetes to survive desiccation. However, the genetic basis for the observed responses is unexplored in actinomycetes, as such studies have thus far been limited to gram-negative bacteria (10, 21). We have completed transcriptomic analyses of air-dried R. jostii RHA1, along with an appropriate control experiment to specifically identify its desiccation responses. This unbiased, genome-wide approach enabled us to identify genes that may be crucial for surviving water stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 (formerly Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1; the species was recently identified by A. L. Jones and M. Goodfellow [personal communication]) cultures were grown at 30°C in Erlenmeyer baffled flasks shaken at 200 rpm in W minimal medium (22) supplemented with 20 mM sodium benzoate (Fisher). Liquid precultures of 50 ml in 125-ml baffled flasks were seeded with RHA1 colonies from W medium agar plates grown on biphenyl vapors (Aldrich). Biphenyl was used as a carbon source to ensure the retention of plasmids in this strain. Experimental cultures of 330 ml in 1-liter baffled flasks were inoculated (1% vol/vol) with a preculture in mid-logarithmic-growth phase, corresponding to an optical density at 600 nm of 2.0.

Desiccation stress treatments.

The following desiccation and control experiments were each conducted with three independent (not concurrent) biological replicates. Mid-logarithmic RHA1 cultures were vacuum filtered onto sterilized 0.45-μm cellulose nitrate membranes (47-mm diameter; Whatman), using 20 ml of culture per membrane, and these were placed in preweighed polystyrene petri dishes. Some membranes were cut into quarter segments for future cell viability assays. The membranes were then placed in an air-tight cabinet maintained at 30°C and a relative humidity of either 20% or 100%, for the desiccation or control experiments, respectively. This point marked time zero of each experiment. Low- and high-humidity conditions were achieved by putting trays of silica gel and water, respectively, below the petri dishes, and the relative humidity was monitored by using a digital hygrometer/thermometer.

Directly after filtration and at nine subsequent time points (30 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 1 week, and 2 weeks), the water content of the cells and the associated water were measured gravimetrically and cell viability was determined by CFU counts. The rate at which cells dried was determined by subtracting the mass of the dry nitrocellulose membrane from the masses of the membranes plus the cells. For the cell viability assay, a quarter membrane with cells was soaked in 10 ml of W medium for approximately 5 min and then vortexed at maximum speed for 1 min. Serial dilutions of the cell suspension were plated on W medium with 1.5% agar plus 20 mM sodium benzoate, with two technical replicates for each time point. Cells from a whole membrane were harvested to extract RNA for transcriptomic analysis. The membrane was placed in 10 ml of W medium and vortexed at maximum speed for 30 s. An equal volume of “stop solution,” 5% phenol (pH 5) in ethanol, was added (4). The cells were collected by centrifugation at 4,900 × g for 10 min at 4°C, suspended in 1.0 ml of the supernatant plus 2.0 ml RNAprotect (Qiagen), and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 2 min at room temperature. The pellet was frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C.

Cryofixation SEM.

Cells were viewed in a frozen state in order to observe any morphological adaptations of desiccated or control cells at various water contents. The advantage of cryofixation scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was that the appearance of the fully or partially hydrated cells, as well as any extracellular material present, was unaltered because the chemical fixation and alcohol dehydration steps of conventional SEM were not employed (39). The samples were not coated with metal, thus eliminating this source of potential artifacts.

At selected time points during three independent desiccation and control experiments, small segments of the membrane plus cells were mounted onto microscope platform stubs by using Tissue-Tek optimal-cutting-temperature compound and then plunged into N2 (l) for storage. Ice from the surface of the samples was sublimated at −90°C for approximately 40 min in a Hitachi S-4700 field emission SEM. Micrographs were taken at an accelerating voltage of 1.0 kV, at a working distance of 12.0 mm, and with no tilt of the cryostage. The lengths of at least 10 fully visible cells from each time point were measured, except where individual cells could not be delimited due to excessive extracellular material.

Transcriptomic analysis.

RNA was extracted from desiccated and control cells originally harvested from 20 ml of culture by adapting previous methods (14). Briefly, total RNA isolation involved vortexing with glass beads and hot phenol plus sodium dodecyl sulfate (final concentrations of 14.3% and 0.9% [vol/vol], respectively); removal of debris with acetate and phenol plus chloroform (4.0 ml phenol-chloroform [1:1, vol/vol]); precipitation of nucleic acids with acetate plus isopropanol; and a single DNase I treatment (15 U; Invitrogen) with incubation at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of RNaseOUT (20 U; Invitrogen). The RNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction (500 μl phenol-chloroform [1:1, vol/vol]), precipitation, and the use of an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen).

cDNA synthesis, indirect Cy-labeling, and microarray hybridizations were performed as described previously (14), with the following modifications. The cDNA synthesis mixture included 1.5 μg random hexamer primers (Invitrogen) per 6.0 μg RNA, which was brought to 15.3 μl with diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. After RNA denaturation for 10 min at 70°C, followed by cooling for 5 min on ice, cDNA synthesis components were added to final concentrations of 0.46 mM each of dATP, dCTP, and dGTP; 0.19 mM dTTP; 0.28 mM aminoallyl-dUTP (Ambion); 0.01 M dithiothreitol; 10 U RNaseOUT; and other ingredients as described previously (14). Equal amounts of differentially labeled cDNA—50 million pixels as measured by ImageQuant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics)—from treated cells versus untreated time-zero cells were hybridized at 42°C for 17 h. After the automated washes, the slides were dipped in 0.2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and dried by centrifugation at 225 × g for 5 min at room temperature. For one of the three hybridizations from each experiment, the Cy3/Cy5 dyes were reversed (i.e., time-zero cDNA was labeled with Cy5 rather than Cy3) to account for dye bias (37). The microarray contained duplicate 70-mer oligonucleotide probes for 8,213 RHA1 genes, representing 89% of the predicted genes (26). The probes were designed and synthesized by Operon Biotechnologies, Inc. (Huntsville, AL).

The microarray spot intensities were quantified by using ImaGene 6.0 (BioDiscovery, Inc.). The average normalized expression ratios were calculated using GeneSpring 7.2 (Silicon Genetics) by the intensity-dependent Lowess method, with 20% of the data used for smoothing. Differentially expressed genes were defined as those that were significantly up- or down-regulated by more than twofold (P < 0.05) in at least three of seven time points in comparison to their expression at time zero. K-means clustering of differentially expressed genes during the desiccation experiment was performed with GeneSpring 7.2 software using a Pearson correlation similarity measure.

Reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

The expression ratios of selected genes were determined relative to the expression of a housekeeping gene encoding a probable DNA polymerase IV (GeneID ro01702). The expression of this housekeeping gene is steady under a variety of growth conditions (14), including the water stress experiments reported here. The primer and TaqMan probe sequences used for qPCR (Table 1) were designed by using the default settings of Primer Express v2.0 software (Applied Biosystems).

TABLE 1.

Quantitative PCR TaqMan primer and probe sequences

| Gene | Function | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| dps1 | Sense primer | 5′CGAGTCGCCGACATACTTCA3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′GCGTCAGATGCAGATCGTTGT3′ | |

| Probea | 5′(6FAM)AAGCGGCTCAGCGC(NFQ)3′ | |

| dps2 | Sense primer | 5′TGAGCCTGATCGCCAAACA3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′GTGGACCGCCAGGAAGTG3′ | |

| Probea | 5′(6FAM)CTGGAATGTCATCGGAC(NFQ)3′ | |

| sigF1 | Sense primer | 5′TGCTGATGTTGCGGTTCTTC3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′ACGCGCTGGGCGATT3′ | |

| Probea | 5′(6FAM)ATCGATGACCCAGACGG(NFQ)3′ | |

| sigF2 | Sense primer | 5′TTGGCCGGACGAGTATCAG3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′CGAGGGCTGCCATCTGTT3′ | |

| Probea | 5′(6FAM)TCACAGCACTCTTC (NFQ)3′ | |

| sigF3 | Sense primer | 5′AATCACTTCCCGACCTCGAA3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′GGGTCATGTTGCCGAAGAA3′ | |

| Probeb | 5′(6FAM)CACCGTGCTGGTCC (TAMRA)3′ | |

| ectA | Sense primer | 5′CGAGATACGGCGATCAACAA3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′TGTCCATCGGGAAAATCGTT3′ | |

| Probea | 5′(6FAM)CAAGAACTGTTCTCCC(NFQ)3′ | |

| DNApol IV | Sense primer | 5′GACAACAAGTTACGAGCCAAGATC3′ |

| Antisense primer | 5′CCTCCGTCAGCCGGTAGAT3′ | |

| Probea | 5′(VIC)CGACGGACTTCGGCA (NFQ)3′ |

5′ 6FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) or VIC fluorophore and 3′ nonfluorescent quencher.

5′ 6FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) fluorophore and 3′ TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine) quencher.

The samples used for the RT-qPCR and microarray analyses were the same. Contaminating genomic DNA, which would not have affected microarray signal intensities, was greatly reduced from certain RNA samples needed for RT-qPCR by one or two DNase treatments as described above, except that the amount of DNase I was increased to 86 U. For cDNA synthesis, the manufacturer's instructions for the Thermoscript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen Life Technologies) were followed, using 1.0 μg of purified RNA and random hexamer primers but only 0.25 μl of RNaseOUT (40 U/μl). Each qPCR reaction mixture consisted of 1.0 μl of the 20 μl of cDNA produced, 200 nM of each primer (except that 400 nM was used for the sigF1 assay), 200 nM TaqMan probe, and 10 μl 2× TaqMan universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) in a total volume of 20 μl. Duplicate singleplex reactions for the gene of interest and the housekeeping gene were run in a Stratagene Mx3000P real-time PCR system for 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and then 40 to 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. The quantitative PCR cycle threshold (CT) results were analyzed by the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT method) followed by Student's one-sample t test to evaluate whether the gene targets were differentially regulated (5). The expression ratios were calculated by using the formula E(−ΔΔCT), where E is the average amplification efficiency derived from the standard curves for the target and housekeeping genes (5).

Microarray data accession number.

Details of the microarray design, transcriptomic experimental design, and transcriptomic data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE10378. Gene annotations updated since the publication of the RHA1 genome (26) are available at http://www.rhodococcus.ca/.

RESULTS

Drying rates and cell survival at low and high relative humidity.

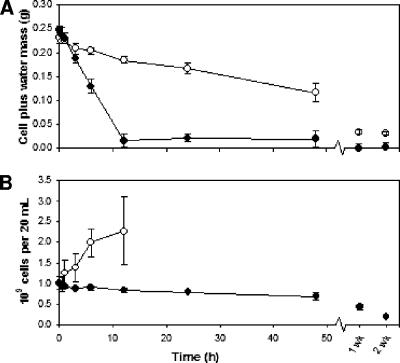

Exponential-phase RHA1 cells were filtered onto membranes and allowed to air dry at a low relative humidity (20%) for up to 2 weeks. Since the cells were subjected to concurrent stresses other than desiccation—most notably, starvation—a control experiment was performed at high relative humidity (100%) such that the cells experienced significantly less water stress. The rate of drying during each treatment was determined gravimetrically (Fig. 1A). The desiccated cells reached a basal minimum mass by 12 h, whereas over that same period, the control cells dried at a rate approximately 5 times lower, reducing their initial mass by half by 48 h. After two weeks, the control cells still had a significantly greater mass, indicating that they had retained some intracellular water compared to the amount in the desiccated cells, whose mass did not differ significantly from the results of dry-weight measurements (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

(A) Loss of water from desiccated (•) or control (○) cells over time. (B) CFU counts of desiccated (•) or control (○) cells over time. The control experiment CFU counts from 24 h and on were confounded by cells adhering to the membrane. Error bars represent standard deviations of the results for three independent cultures.

Cell viability during the desiccation and control experiments was determined by CFU counts of the cell suspensions from vortexed membranes (Fig. 1B). The viability of the desiccated cells gradually decreased over time to a minimum of about 20% after 2 weeks. Conversely, the number of viable control cells more than doubled by 12 h, accompanied by increased variability among replicates. In each control experiment, the cells started adhering to the membrane by 24 h, presumably due to the production of a sticky extracellular substance, which prohibited CFU counts for all subsequent time points. Considering that very little growth substrate would have been available to the filtered cells, we hypothesized that the increase in cell number during the control experiment was due to reductive division and not increased biomass. Desiccated cells were also microscopically examined to decipher whether the overall trend of decreasing CFU counts resulted solely from cell death or from the net contributions of an increase in cell number from reductive division coincident with a greater rate of cell death.

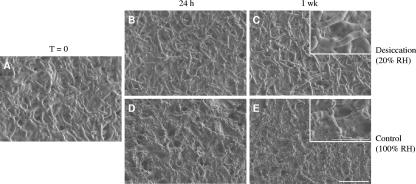

Morphological adaptations.

To observe any morphological adaptations of RHA1 to low or high relative humidity conditions, cryofixation SEM was used to view frozen samples with differing water contents over the experimental time courses. Just after filtration, the cells looked like healthy rods with a smooth cell surface (Fig. 2A). The appearance of the cells after 24 h and 1 week of desiccation did not change (Fig. 2B and C). Also, the average cell length remained constant at 7.5 ± 0.3 μm (mean ± standard error of the mean) during desiccation. Thus, reductive division did not occur and the steady decline in CFU as shown in Fig. 1B corresponds to cell death. In two of three independent control experiments, the cells were clearly embedded in an extracellular substance by 24 h (Fig. 2D and E), consistent with the cells sticking to the membranes at this time during cell viability assays (cf. Fig. 1B). Although the average length of these embedded cells did not appear to differ from that of desiccated cells, the number of prominent septa within the embedded cells did increase, suggesting that cell division occurred without separation. The vortexing step of the cell viability assay may have been forceful enough to break these daughter cells apart, possibly accounting for the observed increase in CFU during the control experiment (cf. Fig. 1B).

FIG. 2.

Cell morphology of R. jostii RHA1 on membranes for over 1 week of desiccation at 20% relative humidity (RH) versus incubation at 100% relative humidity. Micrographs were captured by cryofixation SEM. Scale bars are 10 μm for low-magnification images and 5 μm for high-magnification insets.

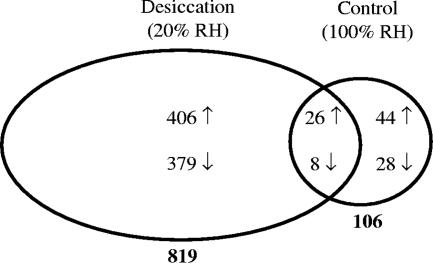

Desiccation-specific transcriptome.

Custom microarrays with probes for 89% of the predicted RHA1 genes were used to profile the transcriptional response of RHA1 during the first 2 days of the desiccation and control experiments. The main objective was to identify genes that were differentially expressed due to the higher rate of drying of the desiccation treatment. The number of genes whose expression changed during desiccation was close to 8 times greater than that in the control experiment (Fig. 3). This disparity in genetic response indicates the severity of the water stress the desiccated cells experienced, requiring large-scale alterations of their transcriptome. The gene expression variability for the control cells was 45% greater than for their desiccated counterparts, which partially explains why they had fewer significantly up- and down-regulated genes; however, if only expression-level-change criteria were considered, such as expression ratios up- or down-regulated by more than fourfold at three of seven time points, the response from the desiccated cells still exceeded that of the control cells by nearly a factor of 4.

FIG. 3.

Numbers of genes differentially regulated in the desiccation and control experiments. A differentially regulated gene was defined as up- or down-regulated (shown by arrows) >2-fold (P < 0.05) for at least three of seven time points relative to time zero. RH, relative humidity.

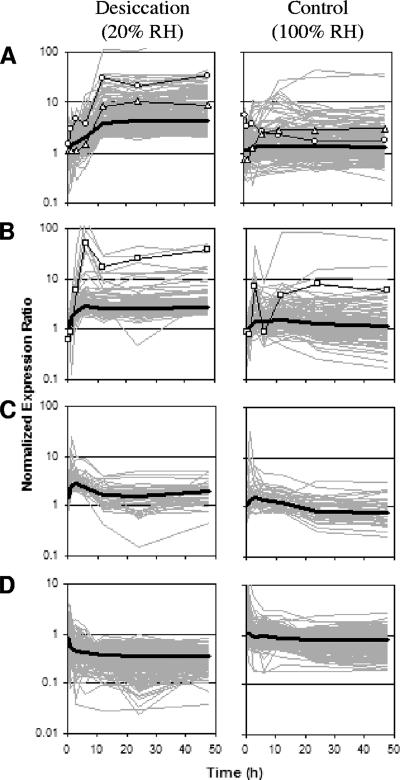

The number of desiccation-specific responses found to be differentially regulated in the desiccation treatment, and not in the control, comprised a total of 406 up-regulated and 379 down-regulated genes (Fig. 3; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The expression profiles of these up-regulated genes clustered into three general patterns. The expression of the largest cluster under desiccating conditions steadily increased up to 12 h and then remained high (Fig. 4A). In general, the expression ratios of the same genes under the control conditions displayed no substantial up-regulation over 2 days. The marked increase in the expression of this group of genes at 12 h of desiccation coincided with the time point at which the desiccated cells reached minimal water content (cf. Figure 1A). Therefore, the genes of this cluster appear to be up-regulated specifically in response to desiccation and are promising candidates for elucidating the mechanisms by which RHA1 survives its dried state. The other two clusters of desiccation-specific up-regulated genes reached their peak expression levels quickly, within a few hours of treatment, with maximum expression ratios generally lower than those of the previous cluster. One cluster was up-regulated early (around 3 h) and stayed up-regulated (Fig. 4B), whereas the smallest gene cluster was up-regulated early (around 1 h) but only transiently (Fig. 4C). For these latter two groups of genes, the medial expression profiles during the control experiment followed trends similar to those in the desiccated cells, but the expression ratios were attenuated in the control cells such that the genes did not pass the significance and expression-level-change cutoffs. This concordance in expression trends under both conditions, with maximum expression ratios occurring while the cells were still relatively well hydrated, suggests that the genes whose expression profiles are shown in Fig. 4B and C are likely responding to common stresses in both treatments, only with heightened urgency in the desiccating cells. Classifying many of these genes as adaptations to common stresses would augment the otherwise small number of genes that satisfied the criteria for up-regulation in both experiments (Fig. 3) and may provide a more-accurate understanding of RHA1's starvation response.

FIG. 4.

Clustering of expression patterns of genes differentially regulated during the desiccation experiment only. Gray lines are the gene expression profiles of the same sets of genes during the desiccation and control experiments. Thick black lines represent the median expression ratios of genes from the respective cluster. The desiccation-specific up-regulated genes clustered into three groups: (A) those up-regulated at 12 h (232 genes, including dps1 [○] and ectA [▵]); (B) those up-regulated early (125 genes, including groL1 [□]); and (C) those up-regulated early but transiently (49 genes). (D) Expression profiles for the 379 desiccation-specific down-regulated genes. RH, relative humidity.

For the 379 desiccation-specific down-regulated genes, the medial expression pattern exhibited an early, sustained decline by 3 h of desiccation, compared to a slight decrease in the expression of the same genes during the control experiment (Fig. 4D). Again, these genes could be clustered into three down-regulation patterns that reached their minimum expression ratios at 12 h (163 genes), at 3 h (114 genes), or, transiently, at 1 h (102 genes) of desiccation; however, in all three cases, these genes showed generally no differential regulation in the control experiment. Thus, desiccation resulted in the prompt down-regulation of many cellular processes not shut down to the same degree in the less-stressed control cells.

We focused further analysis on the up-regulated genes of the desiccation-specific transcriptome in pursuit of the responses directly responsible for desiccation resistance in RHA1. When these genes were categorized according to their predicted functional roles, several groups warranted interest (Table 2). z-score statistics were calculated (when possible) to gauge whether the functional groups were over- or underrepresented in RHA1's desiccation response in comparison to the number of that gene type present in the genome (12). Functional categories with an absolute z-score value of more than 2 were considered to have deviated significantly from the number of differentially regulated genes expected for that group (12). In the desiccation-specific transcriptome, transcriptional regulator genes were far more prevalent than expected by chance. Conversely, genes involved in transport were significantly less abundant than expected. The proportion of up-regulated genes encoding transposases or hypothetical proteins was similar to that expected based on their genomic frequencies. The desiccation-specific transcriptome also had several genes associated with cellular processes, such as cell division, DNA recombination and repair, lipid metabolism, and cell envelope modification (Table 2). The induction of genes involved in each of these functions may reflect adaptations to prevent and survive desiccation-induced damage. Furthermore, with regard to the cell division group, six of the eight genes were up-regulated early in the desiccation treatment (i.e., the expression profiles are clustered in Fig. 4B or C), suggesting that the desiccated cells may have taken initial steps toward cell division but never reductively divided.

TABLE 2.

Functional classification of desiccation-specific up-regulated genes

| Functional category | No. (%) of genes

|

z scorec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desiccation specifica | In genomeb | ||

| Cell division | 8 (2.0) | N/Af | N/A |

| DNA recombination and repair | 7 (1.7) | N/A | N/A |

| Lipid metabolism and cell envelope modification | 23 (5.7) | N/A | N/A |

| Transcriptional regulatorsd | 71 (17.5) | 705 (7.6) | 7.6 |

| Transportersd | 20 (4.9) | 890 (9.6) | −3.3 |

| Transposasese | 6 (1.5) | 199 (2.2) | −1.0 |

| Hypothetical gene productsd | 138 (34.0) | 3,509 (38.0) | −1.7 |

Total desiccation-specific up-regulated transcriptome contains 406 genes.

Total genome contains 9,225 genes.

z scores were calculated as described by Doniger et al. (12), except that genomic figures were used to approximate the number of genes measured by our microarray.

Number in genome taken from McLeod et al. (26).

Number in genome determined by keyword search of gene annotations.

N/A, not available.

Desiccation-specific genes up-regulated at 12 h.

Cluster analysis of the desiccation-specific transcriptome identified a group of genes that were increasingly expressed with drying. One of the most highly up-regulated desiccation-specific genes was dps1, encoding a DNA protection during starvation protein (1). The expression of dps1 resembled the typical expression pattern for genes up-regulated at 12 h of desiccation (Fig. 4A). Two conserved hypothetical genes (GeneID ro00102 and ro00103) contiguous with dps1, as well as two nearby but divergently transcribed genes encoding a sigma factor, SigF1, and an anti-sigma factor (ro00098 and ro00099), were all up-regulated during desiccation, with expression profiles that correlated by more than 99% with that of dps1. Other groups of genes also shared this pattern of regulation with at least 95% correlation, including genes encoding another sigma factor, SigF3, and a probable transcriptional regulator of the MerR family (ro04728 and ro04729); a possible oxidoreductase, a dehydrogenase, and a possible cation transport regulator (ro05505 to ro05507); a possible (p)ppGpp synthetase (ro08290), situated in between genes for a possible transcriptional regulator and a conserved hypothetical protein (ro08289 and ro08291); and, also of interest, a catalase (ro04309). The simultaneous responses of these desiccation-specific genes suggest a common regulatory network. The two alternative sigma factors (group 3 subdivision of the σ70 family), SigF1 and SigF3, are likely involved in the regulation of this network, but the signal(s) to which each responds and the genes that each transcribes cannot yet be deduced. A third gene encoding a highly similar sigma factor of this subdivision, sigF2 (ro02118), did not have a microarray probe, so its expression was determined by RT-qPCR (Table 3). Unlike its other two paralogs in RHA1, sigF2 was not differentially expressed at 12 h during either experiment (Table 3), suggesting that SigF2 has a different physiological role than the other two sigma factors.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative PCR and microarray expression ratiosa at 12 h compared to time zero

| GeneID | Gene name | Expression ratio in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desiccation expt (20% relative humidity)

|

Control expt (100% relative humidity)

|

||||

| Microarray | qPCR | Microarray | qPCR | ||

| ro00101 | dps1 | 31b | 33b | 2.2 | 1.3 |

| ro08251 | dps2 | 2.8b | 3.5b | 1.3 | 1.6b |

| ro00098 | sigF1 | 6.9b | 7.7b | 1.7 | 4.3b |

| ro02118 | sigF2 | N/Ac | −1.6 | N/A | 1.3 |

| ro04728 | sigF3 | 31b | 58b | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| ro01305 | ectA | 8.3b | 10.7b | 2.8 | 2.2 |

Average normalized expression ratios (n = 3). Negative expression ratios indicate down-regulation.

Significant change in expression between 12 h of treatment and time zero (P < 0.05).

N/A, not available.

Two genes encoding enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway for the compatible solute ectoine, ectA and ectC (GeneID ro1305 and ro1307), were also part of the desiccation-specific cluster of genes up-regulated at 12 h (ectA expression is displayed in Fig. 4A). The third gene of ectoine biosynthesis, ectB (ro01306), had no probe on the microarray. Both the desiccated and control cells would have experienced osmotic stress during their incubations out of liquid culture; however, the reduced severity of this stress in the control experiment is evident by the similar but attenuated expression profile of ectA during that treatment (Fig. 4A). The only other response associated with compatible solute production was the up-regulation of an α,α-trehalose-phosphate synthase (ro00090), just one of six trehalose metabolism genes annotated in the RHA1 genome. Two genes adjacent to this trehalose metabolism gene, encoding a conserved hypothetical protein and a hypothetical protein (ro00088 and ro00089), shared similar expression trends during desiccation (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Genes from desiccation-specific transcriptome discussed in text

| GeneID | Gene name | Description of gene product | Maximum expression ratioa | Cluster patternb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ro00088 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.7 | A | |

| ro00089 | Hypothetical protein | 11 | A | |

| ro00090 | α,α-Trehalose-phosphate synthase (UDP forming) | 4.9 | A | |

| ro00098 | sigF1 | σ70 type, group 3 subdivision | 8.9 | A |

| ro00099 | Anti-σ factor, possible RsbW | 3.4 | A | |

| ro00101 | dps1 | DNA protection during starvation protein | 35 | A |

| ro00102 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 20 | A | |

| ro00103/ro08731c | Conserved hypothetical protein/possible transglycosylase | 12 | A | |

| ro00441 | prmA | Propane monooxygenase hydroxylase large subunit | 348 | B |

| ro00442 | prmB | Propane monooxygenase reductase | No probe | |

| ro00443 | prmC | Propane monooxygenase hydroxylase small subunit | 40 | B |

| ro00444 | prmD | Propane monooxygenase coupling protein | 55 | B |

| ro00445 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 167 | B | |

| ro00446 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 60 | B | |

| ro00447 | prmE | Alcohol dehydrogenase | 97 | B |

| ro00448 | groL1 | 60-kDa chaperonin GroEL | 52 | B |

| ro00914 | Probable AMP-dependent acyl-coenzyme A synthetase | 4.3 | B | |

| ro00915 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 5.5 | B | |

| ro00916 | Short chain dehydrogenase | 6.6 | B | |

| ro01305 | ectA | Probable acetyltransferase | 10.4 | A |

| ro01306 | ectB | Probable diaminobutyrate-pyruvate aminotransferase | No probe | |

| ro01307 | ectC | l-Ectoine synthase | 3.5 | A |

| ro02122 | Isocitrate lyase | 8.2 | C | |

| ro04049 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 5.5 | B | |

| ro04050 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 4.6 | B | |

| ro04051 | Probable stage II sporulation protein | 2.8 | B | |

| ro04309 | Catalase | 4.3 | A | |

| ro04728 | sigF3 | σ70-type, group 3 subdivision | 33 | A |

| ro04729 | Probable transcriptional regulator, MerR family | 20 | A | |

| ro05275 | katG | Catalase | 6.7 | B |

| ro05505 | Possible oxidoreductase | 6.0 | A | |

| ro05506 | Dehydrogenase | 4.6 | A | |

| ro05507 | Possible cation transport regulator | 9.1 | A | |

| ro05911 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit C | 2.5 | C | |

| ro05915 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit G | 4.3 | C | |

| ro05917 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit I | 2.9 | C | |

| ro05918 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit J | 4.0 | C | |

| ro05919 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit K | 3.7 | C | |

| ro05920 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit L | 26 | C | |

| ro05921 | Probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit M | 9.0 | C | |

| ro07195 | Probable transcriptional regulator | 16 | A | |

| ro07196 | sufB | FeS assembly protein | 18 | A |

| ro07197 | sufD | FeS assembly protein | 8.7 | A |

| ro07198 | sufC | FeS assembly ATPase | 9.0 | A |

| ro07199 | sufS | Selenocysteine lyase | 4.5 | A |

| ro07200 | Probable Fe-S assembly protein | 3.6 | B | |

| ro07201 | Possible metal-sulfur cluster protein | 3.2 | B | |

| ro08251 | dps2 | Starvation-response DNA binding protein | 4.3 | A |

| ro08289 | Possible transcriptional regulator | 9.7 | A | |

| ro08290 | Possible (p)ppGpp synthetase | 21 | A | |

| ro08291 | Probable transcriptional regulator | 15 | A |

Maximum average normalized expression ratio (n = 3) attained during the desiccation time course.

Cluster pattern expression profiles are shown in Fig. 4.

Probe cross-hybridizes with two genes.

Congruency between microarray and RT-qPCR results.

The expression ratios determined by microarray and RT-qPCR analyses at the 12-h time point of the desiccation and control experiments agreed well (Table 3). In separate studies, our custom RHA1 microarray slides were validated by RT-qPCR for nine other genes, with reference to the same housekeeping gene used in the present study (14, 34, 38). As a result, we have confidence in the validity of the microarray expression ratios. RT-qPCR verified the significant up-regulation of genes believed to play important roles specific to desiccation tolerance, including dps1, sigF3, and ectA. In the case of sigF1, its desiccation-specific microarray expression profiles and RT-qPCR expression ratios were not in complete agreement. RT-qPCR showed significant up-regulation of sigF1 in both experiments, although its up-regulation was still 1.8 times greater during desiccation. The expression of dps2 (GeneID ro08251), encoding a paralog of Dps1 with 37% amino acid identity, was also confirmed by RT-qPCR to be up-regulated during desiccation but to a much lesser extent than dps1—only about 3-fold as opposed to more than 30-fold, respectively. If this large difference in gene expression is indicative of protein abundance, then Dps2 is likely to contribute less than Dps1 to desiccation resistance.

Genes up-regulated early in response to common starvation stress.

Of the genes clustered in groups up-regulated early in desiccation, some of the most highly up-regulated responses belonged to two large putative operons. Seven genes from each putative operon were significantly up-regulated in only the desiccation treatment but followed similar, attenuated expression patterns in the control. Each set of genes was likely cotranscribed, since the expression profiles of at least six of the seven members correlated by more than 90% during both treatments.

Genes in the first of these putative operons (GeneID ro00441 to ro00448), with members that encode a propane monooxygenase enzyme (prmABCD), all clustered in the up-regulated-early pattern (Table 4). This large operon, including prmB (ro00442), for which our microarray lacked a probe, is induced in propane-grown RHA1 (34). In addition to the functional role of these genes in propane catabolism, their expression was also greatly increased when RHA1 was grown on 5 mM phenol (unpublished data), an organic-solvent stress. The expression of this operon during organic-solvent stress and the starvation stress in both treatments of the present study (groL1 expression, displayed in Fig. 4B) suggests that it may be part of a general stress response. How the propane monooxygenase would contribute to such a stress response is unclear, but the GroEL chaperonin protein and, perhaps, the conserved hypothetical proteins encoded near the end of this operon may have important functions under a range of cellular stresses where macromolecular stability is jeopardized.

The second putative operon consists of genes annotated as probable NADH dehydrogenase subunits (GeneID ro05909 to ro05922), and their expression profiles clustered in the pattern of early but transient up-regulation (Table 4). This strong response of half of the 14 contiguous probable NADH dehydrogenase subunit genes likely represents an important adjustment of aerobic respiration in the starved cells from both treatments. Transient up-regulation of these genes has also been observed in the early stationary phase of carbon-starved RHA1 batch cultures, but not in nitrogen-starved ones (unpublished data). Other putative operons and highly expressed genes with expression trends during both experiments that indicate that they may have responded to common stresses include genes encoding a probable AMP-dependent acyl-coenzyme A synthetase, a conserved hypothetical protein, and a short-chain dehydrogenase (ro00914 to ro00916); an isocitrate lyase (ro02122); a probable stage II sporulation protein downstream of two conserved hypothetical proteins (ro04049 to ro04051); a KatG catalase (ro05275); and an FeS assembly pathway (ro07195 to ro07199).

DISCUSSION

Veritable desiccation resistance.

We have presented the first genome-wide study of the transcriptional response of a gram-positive bacterium to desiccation. In studies that have compared the survival of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria during air drying, the gram-positive species have consistently proven themselves better adapted to dry conditions (20, 42, 44). In particular, actinomycetes have long been considered dry-soil specialists, since their proportion within a bacterial community increases in arid regions (27). Here, we found that one-fifth of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 cells survived 2 weeks of desiccation at 20% relative humidity and 30°C. The cyanobacterium and gammaproteobacterium species for which the two other desiccation transcriptomes have been determined were less tolerant than RHA1 to their (less harsh) air-drying treatments: fewer than 1% of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 cells survived after only 22 h at 30% relative humidity (21), and approximately 1 to 2% of Bradyrhizobium japonicum cells survived after 3 days at 27% relative humidity (when the initial cell count was conservatively estimated at 108 CFU/ml) (10). RHA1, as a member of a truly desiccation-tolerant phylum, may be protected from air drying by features inherent to gram-positive cell walls, in addition to the presumably beneficial genetic responses to water stress identified in this study.

Electron microscopy of RHA1 revealed that the integrity of its cell membrane did not change over 1 week of desiccation. Whether this reflects a special adaptation is difficult to ascertain, since the only published micrographs of dried bacteria are of ones considered to be relatively desiccation tolerant. One would expect that desiccation-sensitive bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, which largely succumbs to desiccation in less than a day (18), would leave visibly damaged cells as they dried. This idea is supported by the instability and folding of cell membranes observed in dehydrated E. coli K-12 cells subjected to hyperosmotic shock (28). Like RHA1, a close relative, R. opacus PD630, maintained a healthy ultrastructure during desiccation (2). After 60 days at 20% relative humidity, the proportion of coccoidal PD630 cells had increased, although the majority were still filamentous, and the cells were embedded in an EPS-like matrix (2). We found possible evidence for reductive division and EPS production by RHA1 in only the control treatment. Perhaps the intense and sudden water stress endured by the desiccated cells hindered these seemingly advantageous adaptations to air drying that were possible in the more gradually dried control cells.

Multiple observations in this study indicate that the desiccated cells experienced greater stress than the cells incubated at high relative humidity. Relative to the control cells, the desiccated cells (i) dried significantly faster, (ii) failed to increase in cell number, (iii) had a greater number of differentially regulated genes, (iv) had greater changes in levels of gene expression, and (v) exhibited clearer, less-variable trends with respect to cell viability, morphology, and gene expression. The greater variability of the control cells suggests that the milder water stress they experienced neared a threshold for the induction of certain desiccation responses such that only some were expressed and most of those were weakly expressed. These observations support conclusions based on the premise that the differences in responses between the treatments reflect adaptations to desiccation stress.

Mechanisms of protection from desiccation-induced damage.

High up-regulation of dps1 upon drying was one of the most notable responses of RHA1. Since the discovery of Dps in starved E. coli cells (1), orthologs of this protein have been found throughout the bacterial domain and in one archaeon so far (29). Dps has been shown to protect DNA under a variety of stresses (29). The closest biochemically characterized homolog of Dps1 from RHA1 is the gene encoding DpsMs from Mycobacterium smegmatis (8). DpsMs and all other purified Dps proteins have ferroxidase activity and can bind and sequester iron in their dodecameric form (8), preventing the production of hydroxyl radicals through Fenton chemistry (46). Accordingly, the protection from oxidative stress imparted by this protein is well documented (1, 3, 19, 24, 30). Some Dps homologs, including DpsMs, can also bind nonspecifically to double-stranded DNA (8). In starved E. coli cells, Dps-DNA complexes biocrystallize (43), thereby sequestering DNA. Thus, Dps may additionally act as a protective shield for DNA against damaging agents, such as nucleases and oxidative radicals (15, 29).

Even though one of the consequences of water stress is known to be increased reactive oxygen species (9, 25), no previous study has suggested that Dps might help desiccation tolerance. However, the dps gene of Deinococcus radiodurans was significantly up-regulated in response to γ-irradiation, presumably conferring protection from the resulting oxidative radicals (36). In fact, the remarkable resistance of D. radiodurans to ionizing radiation is believed to be a consequence of its adaptation to dry environments (25). The Dps homolog in E. coli was also found to protect stationary-phase cells from UV and γ-irradiation (29). The association of oxidative stress with the cellular assaults imposed by both γ radiation and desiccation strengthens the prospect that Dps is a critical desiccation survival mechanism in RHA1.

The sigma factor genes correlated with dps1 expression during desiccation in RHA1 are related to genes known to regulate the expression of dps orthologs in two other gram-positive bacteria, Bacillus subtilis and a fellow actinomycete, Streptomyces coelicolor. The expression of dps is dependent upon SigB in response to several stresses in B. subtilis, including starvation, salt, heat, and ethanol treatments (3), and to salt stress in S. coelicolor (23). Previous studies have never directly associated Dps with desiccation resistance, but such a function is consistent with a report by Volker et al. that a sigB-null mutant of B. subtilis is 10 times more sensitive to lyophilization than the wild type (40). In RHA1, the three SigF proteins have the highest sequence identities to the SigB proteins from B. subtilis and S. coelicolor. Furthermore, in addition to being up-regulated during desiccation stress, dps1 and sigF3 of RHA1 were also up-regulated following heat and salt stresses, according to the results of separate microarray experiments (unpublished data). These results suggest that SigF3 may regulate genes involved in resistance to a broader range of stresses than SigF1, although either or both could be responsible for the large transcriptional response after 12 h of desiccation. The simultaneous up-regulation of sigF3 and dps1 during desiccation, osmotic, and heat stresses, as well as the potential conservation in RHA1 of the regulatory relationship seen in B. subtilis and S. coelicolor, all suggest a role for SigF3 in dps1 expression.

To cope with the osmotic stress inherent in water evaporating off of drying cells, RHA1 up-regulated the expression of genes needed to synthesize ectoine and, to a lesser degree, trehalose. These two organic solutes are listed as predominant osmoprotectants found in actinomycetes (41), and they may be particularly prevalent in rhodococci, since they accumulate in desiccated R. opacus PD630 cells grown on different carbon sources than used in our study (2). Ectoine is likely the primary compatible solute in RHA1, because its biosynthetic pathway was a common response in both the desiccation and osmotic stress transcriptomes (13). These studies of RHA1 used benzoate as the growth substrate, so whether other compatible solutes would be preferentially synthesized on other growth substrates is unknown. Nevertheless, the ability to synthesize ectoine appears to be an important contributor to the desiccation resistance of RHA1. In general, this compatible solute is restricted to halophilic and marine bacteria that thrive in salty environments, and so, it may confer exceptional osmotolerance (7).

Comparison of bacterial desiccation responses.

To date, whole-genome transcriptional analyses have been conducted for three desiccated bacterial species: the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 (microarray probes were not gene specific, however) (21), the gammaproteobacterium B. japonicum (10), and the actinomycete R. jostii RHA1. Important responses found in all three studies included genes for the synthesis of compatible solutes, protection from oxidative damage, transcriptional regulation, and cell envelope modification. Results from the Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 and B. japonicum transcriptomes both support previous findings that trehalose is a major compatible solute in these bacteria when desiccated (17, 35). By contrast, RHA1 induced its ectoine biosynthetic pathway. To neutralize reactive oxygen species, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 up-regulates a catalase (21) and B. japonicum up-regulates peroxidases and superoxide dismutases (10). RHA1 did induce two catalases (Table 4), but its predominant antioxidant response was the induction of dps1. Knockout mutagenesis of these unique genetic responses will be needed to establish their contributions to RHA1's fitness during desiccation. Other commonalities between the desiccation responses of RHA1 and B. japonicum were genes involved in DNA modification, repair, and transposition (10). Furthermore, both of these desiccated bacteria up-regulated a gene encoding isocitrate lyase, part of the glyoxylate shunt. Since this gene was characterized as a common stress response in RHA1, we propose that it was up-regulated to utilize acetate produced through catabolism of endogenous triacylglyceride storage compounds and lipids from the cell wall. Lastly, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 and B. japonicum both induce heat shock and chaperonin proteins in response to desiccation (10, 21). RHA1 did up-regulate a chaperonin, groL1, plus a possible (p)ppGpp synthetase, which controls levels of the alarmone (p)ppGpp (6), during desiccation. Additionally, the induction of two general stress genes encoding a chaperonin and a heat shock protein (GeneID ro08345 and ro08348) were appropriately found to be common responses in RHA1 to both the desiccation and control experiments (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

The genetic mechanisms induced by R. jostii RHA1 during desiccation stress represent our most detailed insight thus far into how desiccation-resistant bacteria are able to persist under conditions of low water activity. And, with regard to the special bioremediation capabilities of RHA1, understanding the key mechanisms involved in its desiccation resistance may enable the effective decontamination of polluted soils in arid and semiarid regions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Derrick Horne for technical assistance with cryofixation microscopy and Héctor Alvarez for technical advice and helpful discussions.

This work was funded by a grant from Genome Canada/Genome BC and a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). J.C.L. was supported by postgraduate fellowships from NSERC.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 March 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almiron, M., A. J. Link, D. Furlong, and R. Kolter. 1992. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 6:2646-2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez, H. M., R. A. Silva, A. C. Cesari, A. L. Zamit, S. R. Peressutti, R. Reichelt, U. Keller, U. Malkus, C. Rasch, T. Maskow, F. Mayer, and A. Steinbuchel. 2004. Physiological and morphological responses of the soil bacterium Rhodococcus opacus strain PD630 to water stress. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 50:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antelmann, H., S. Engelmann, R. Schmid, A. Sorokin, A. Lapidus, and M. Hecker. 1997. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor σB in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:7251-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein, J. A., A. B. Khodursky, P.-H. Lin, S. Lin-Chao, and S. N. Cohen. 2002. Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:9697-9702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bio-Rad. 2005. Real-time PCR applications guide. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA.

- 6.Braeken, K., M. Moris, R. Daniels, J. Vanderleyden, and J. Michiels. 2006. New horizons for (p)ppGpp in bacterial and plant physiology. Trends Microbiol. 14:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cánovas, D., C. Vargas, F. Iglesias-Guerra, L. N. Csonka, D. Rhodes, A. Ventosa, and J. J. Nieto. 1997. Isolation and characterization of salt-sensitive mutants of the moderate halophile Halomonas elongata and cloning of the ectoine synthesis genes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25794-25801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceci, P., A. Ilari, E. Falvo, L. Giangiacomo, and E. Chiancone. 2005. Reassessment of protein stability, DNA binding, and protection of Mycobacterium smegmatis Dps. J. Biol. Chem. 280:34776-34785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowe, L. M., and J. H. Crowe. 1992. Anhydrobiosis: a strategy for survival. Adv. Space Res. 12:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cytryn, E. J., D. P. Sangurdekar, J. G. Streeter, W. L. Franck, W.-S. Chang, G. Stacey, D. W. Emerich, T. Joshi, D. Xu, and M. J. Sadowsky. 2007. Transcriptional and physiological responses of Bradyrhizobium japonicum to desiccation-induced stress. J. Bacteriol. 189:6751-6762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davet, P. 2004. Microbial ecology of the soil and plant growth. Science Publishers, Inc., Enfield, NH.

- 12.Doniger, S. W., N. Salomonis, K. D. Dahlquist, K. Vranizan, S. C. Lawlor, and B. R. Conklin. 2003. MAPPFinder: using Gene Ontology and GenMAPP to create a global gene-expression profile from microarray data. Genome Biol. 4:R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekpanyaskun, P. 2006. Transcriptomic analysis of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 responses to heat shock and osmotic stress. M.S. thesis. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

- 14.Gonçalves, E. R., H. Hara, D. Miyazawa, J. E. Davies, L. D. Eltis, and W. W. Mohn. 2006. Transcriptomic assessment of isozymes in the biphenyl pathway of Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6183-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta, S., and D. Chatterji. 2005. Stress responses in mycobacteria. IUBMB Life 57:149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurtler, V., B. C. Mayall, and R. Seviour. 2004. Can whole genome analysis refine the taxonomy of the genus Rhodococcus? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:377-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higo, A., H. Katoh, K. Ohmori, M. Ikeuchi, and M. Ohmori. 2006. The role of a gene cluster for trehalose metabolism in dehydration tolerance of the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Microbiology 152:979-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiramatsu, R., M. Matsumoto, K. Sakae, and Y. Miyazaki. 2005. Ability of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. to survive in a desiccation model system and in dry foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6657-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong, Y., G. Wang, and R. J. Maier. 2006. Helicobacter hepaticus Dps protein plays an important role in protecting DNA from oxidative damage. Free Radic. Res. 40:597-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janning, B., P. H. In't Veld, S. Notermans, and J. Krämer. 1994. Resistance of bacterial strains to dry conditions: use of anhydrous silica gel in a desiccation model system. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 77:319-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoh, H., R. K. Asthana, and M. Ohmori. 2004. Gene expression in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC7120 under desiccation. Microb. Ecol. 47:164-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimbara, K., T. Hashimoto, M. Fukuda, T. Koana, M. Takagi, M. Oishi, and K. Yano. 1989. Cloning and sequencing of two tandem genes involved in degradation of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl to benzoic acid in the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading soil bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J. Bacteriol. 171:2740-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, E.-J., N. Karoonuthaisiri, H.-S. Kim, J.-H. Park, C.-J. Cha, C. M. Kao, and J.-H. Roe. 2005. A master regulator σB governs osmotic and oxidative response as well as differentiation via a network of sigma factors in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1252-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez, A., and R. Kolter. 1997. Protection of DNA during oxidative stress by the nonspecific DNA-binding protein Dps. J. Bacteriol. 179:5188-5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattimore, V., and J. R. Battista. 1996. Radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans: functions necessary to survive ionizing radiation are also necessary to survive prolonged desiccation. J. Bacteriol. 178:633-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLeod, M. P., R. L. Warren, W. W. L. Hsiao, N. Araki, M. Myhre, C. Fernandes, D. Miyazawa, W. Wong, A. L. Lillquist, D. Wang, M. Dosanjh, H. Hara, A. Petrescu, R. D. Morin, G. Yang, J. M. Stott, J. E. Schein, H. Shin, D. Smailus, A. S. Siddiqui, M. A. Marra, S. J. M. Jones, R. Holt, F. S. L. Brinkman, K. Miyauchi, M. Fukuda, J. E. Davies, W. W. Mohn, and L. D. Eltis. 2006. The complete genome of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 provides insights into a catabolic powerhouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:15582-15587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meiklejohn, J. 1957. Numbers of bacteria and actinomycetes in a Kenya soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 8:240-247. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mille, Y., L. Beney, and P. Gervais. 2003. Magnitude and kinetics of rehydration influence the viability of dehydrated E. coli K-12. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 83:578-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair, S., and S. E. Finkel. 2004. Dps protects cells against multiple stresses during stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 186:4192-4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen, K. N., M. H. Larsen, C. G. M. Gahan, B. Kallipolitis, X. A. Wolf, R. Rea, C. Hill, and H. Ingmer. 2005. The Dps-like protein Fri of Listeria monocytogenes promotes stress tolerance and intracellular multiplication in macrophage-like cells. Microbiology 151:925-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philippis, R., and M. Vincenzini. 1998. Exocellular polysaccharides from cyanobacteria and their possible applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:151-175. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prescott, L. M., J. P. Harley, and D. A. Klein. 1996. Microbiology, 3rd ed. W. C. Brown Publishers, Dubuque, IA.

- 33.Pucci, O. H., M. A. Bak, S. R. Peressutti, I. Klein, C. Härtig, H. M. Alvarez, and L. Wünsche. 2000. Influence of crude oil contamination on the bacterial community of semiarid soils of Patagonia (Argentina). Acta Biotechnol. 20:129-146. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharp, J. O., C. M. Sales, J. C. LeBlanc, J. Liu, T. K. Wood, L. D. Eltis, W. W. Mohn, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 2007. An inducible propane monooxygenase is responsible for N-nitrosodimethylamine degradation by Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6930-6938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streeter, J. G. 2003. Effect of trehalose on survival of Bradyrhizobium japonicum during desiccation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:484-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka, M., A. M. Earl, H. A. Howell, M.-J. Park, J. A. Eisen, S. N. Peterson, and J. R. Battista. 2004. Analysis of Deinococcus radiodurans's transcriptional response to ionizing radiation and desiccation reveals novel proteins that contribute to extreme radioresistance. Genetics 168:21-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tseng, G. C., M.-K. Oh, L. Rohlin, J. C. Liao, and W. H. Wong. 2001. Issues in cDNA microarray analysis: quality filtering, channel normalization, models of variations and assessment of gene effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:2549-2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van der Geize, R., K. Yam, T. Heuser, M. H. Wilbrink, H. Hara, M. C. Anderton, E. Sim, L. Dijkhuizen, J. E. Davies, W. W. Mohn, and L. D. Eltis. 2007. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:1947-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Doorn, W. G., F. Thiel, and A. Boekestein. 1990. Cryoscanning electron microscopy of a layer of extracellular polysaccharides produced by bacterial colonies. Scanning 12:297-299. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volker, U., B. Maul, and M. Hecker. 1999. Expression of the σB-dependent general stress regulon confers multiple stress resistance in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:3942-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welsh, D. T. 2000. Ecological significance of compatible solute accumulation by micro-organisms: from single cells to global climate. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:263-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams, S. T., M. Shameemullah, E. T. Watson, and C. I. Mayfield. 1972. Studies of the ecology of actinomycetes in soil. VI. The influence of moisture tension on growth and survival. Soil Biol. Biochem. 4:215-225. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf, S. G., D. Frenkiel, T. Arad, S. E. Finkel, R. Kolter, and A. Minsky. 1999. DNA protection by stress-induced biocrystallization. Nature 400:83-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie, X., Y. Li, T. Zhang, and H. H. P. Fang. 2006. Bacterial survival in evaporating deposited droplets on a teflon-coated surface. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73:703-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada, A., H. Kishi, K. Sugiyama, T. Hatta, K. Nakamura, E. Masai, and M. Fukuda. 1998. Two nearly identical aromatic compound hydrolase genes in a strong polychlorinated biphenyl degrader, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2006-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao, G., P. Ceci, A. Ilari, L. Giangiacomo, T. M. Laue, E. Chiancone, and N. D. Chasteen. 2002. Iron and hydrogen peroxide detoxification properties of DNA-binding protein from starved cells. A ferritin-like DNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27689-27696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.