Abstract

Environmental conditions under which fitness tradeoffs of plasmid carriage are balanced to facilitate plasmid persistence remain elusive. Periodic selection for plasmid-encoded traits due to the spatial and temporal variation typical in most natural environments (such as soil particles, plant leaf and root surfaces, gut linings, and the skin) may play a role. However, quantification of selection pressures and their effects is difficult at a scale relevant to the bacterium in situ. The present work describes a novel experimental system for such fine-scale quantification, with conditions designed to mimic the mosaic of spatially variable selection pressures present in natural surface environments. The effects of uniform and spatially heterogeneous mercuric chloride (HgCl2) on the dynamics of a model community of plasmid-carrying, mercury-resistant (Hgr) and plasmid-free, mercury-sensitive (Hgs) pseudomonads were compared. Hg resulted in an increase in the surface area occupied by, and therefore an increase in the fitness of, Hgr bacteria relative to Hgs bacteria. Uniform and heterogeneous Hg distributions were demonstrated to result in different community structures by epifluorescence microscopy, with heterogeneous Hg producing spatially variable selection landscapes. The effects of heterogeneous Hg were only apparent at scales of a few hundred micrometers, emphasizing the importance of using appropriate analysis methods to detect effects of environmental heterogeneity on community dynamics. Heterogeneous Hg resulted in negative frequency-dependent selection for Hgr cells, suggesting that sporadic selection may facilitate the discontinuous distribution of plasmids through host populations in complex, structured environments.

Bacteria in natural environments tend to live associated with a surface where movement is restricted and cells occupy a spatial niche (11, 13). Such a spatial structure may produce physiochemical gradients and patchiness, resulting in highly heterogeneous local conditions. This is true even for simple experimental biofilms where every effort has been made to maintain constant conditions. For example, Xu et al. (65) demonstrated a decrease in dissolved oxygen concentration in experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms from 0.25 mg liter−1 at the biofilm-bulk fluid interface to <0.1 mg liter−1 approximately 60 μm below the surface. The physical (“nooks and crannies”), chemical (diverse nutrients and toxins), and biological (competition, cooperation, predation, and parasitism) complexities of environmental biofilms further contribute to their heterogeneity. These complexities may have dramatic impacts on microbial community structure and function. In soil, for example, the metabolic potential of the microbial community may differ by as much as 10,000-fold in samples less than 1 cm apart (2).

Environmental heterogeneity has long been implicated in the generation and maintenance of biodiversity in macroorganisms (41, 46) and more recently in microorganisms (67). Explicit evidence for this has come from experimental evolution studies. Rainey and Travisano (47) demonstrated that adaptive radiation and sustained diversification of P. fluorescens populations were apparent in static broth cultures but not in well-mixed cultures. Also, Christensen et al. (9) reported a stable symbiosis between two species in a biofilm not present in planktonic communities. Moreover, Hansen et al. (27) recently described a stable symbiosis between two species dependent on both the spatial structure of a biofilm environment and the adaptive radiation of one of the species.

As well as adaptive radiation, horizontal gene transfer is recognized as an important force in the generation of bacterial diversity (16, 24, 30, 43; see also references 20 and 32), and it is likely that environmental conditions play a role in the frequency and success of transfer events. Certainly, a number of studies have shown this to be the case for the transfer of plasmids, an important class of mobile genetic elements. For example, the geometry of surface habitats may limit contact between donor and recipient cells, and therefore decrease rates of horizontal transfer, when cell densities are low (53). However, there may also be factors in natural surface environments, such as high localized nutrient levels and water flow, that promote cell-to-cell contact and therefore increase rates of horizontal transfer (62).

Plasmids often carry genes that benefit the bacterial cell, such as those that encode resistance to antibiotics and heavy metals. However, such genes are only beneficial when particular selection pressures are in place, and the benefit is countered by a permanent, but potentially small, fitness burden that results in a reduced host growth rate in the absence of selection. The causes of this burden remain unclear but may be related to plasmid-encoded protein expression levels (10), costs associated with replication and maintenance of the plasmids themselves (4), and/or alteration of the cellular regulatory status (15). This context-dependent tradeoff between benefit and burden has serious implications for plasmid persistence. In theory, plasmid numbers in a population may only be maintained if plasmid-carrying hosts are, on average, at least as fit as plasmid-free hosts or if horizontal transfer proceeds at such a rate as to negate the burden of plasmid carriage (3). However, it has been suggested that horizontal transfer is unlikely to proceed at such a rate to enable plasmids to persist as “genetic parasites,” i.e., via horizontal transfer alone, in the majority of cases (3, 33).

Much of the work to date on plasmid persistence has been either theoretical or, if in vitro, carried out with laboratory strains and naïve plasmid-host associations. In situ studies have elucidated the influence of environmental conditions on the horizontal transfer of plasmids (see references 14, 17, 28, and 62 for reviews), facilitated by the advent of sophisticated microscopic and molecular techniques such as confocal epifluorescence microscopy and fluorescent labeling. However, the effect of environmental conditions on the subsequent survival and outgrowth of plasmid-carrying bacteria is a frequently overlooked component of plasmid persistence (20).

Mercury resistance (Hgr) has been used as a selective marker for exogenously isolating plasmids from natural environments, including soil (18, 38, 52, 54), seawater and marine sediment (12, 40, 50), and river epilithon (29). Of all the bacterial Hgr mechanisms, resistance to mercuric Hg [Hg(II)] encoded by genes comprising the mer operon is the best understood (44). The process is one of enzymatic reduction of Hg(II) to elemental mercury [Hg(0)] by mercuric reductase (MerA). Hg(0) then diffuses out of the cell and is removed from the local environment by volatilization. A substantial body of work exists that has aimed to genetically (38, 58, 60, 64, 66) and ecologically (34-37, 39) characterize a group of Hgr plasmids exogenously isolated from the phytosphere of sugar beet in Wytham, Oxfordshire (34), and collectively known as the pQBR plasmids. This collection represents a significant resource for investigation of the benefit and burden of plasmid carriage in environmentally relevant contexts. A representative of the pQBR plasmid family, pQBR103, is, at 425 kb, the largest self-transmissible plasmid yet sequenced from the phytosphere (58). Of the 478 predicted coding sequences, 80% could not be ascribed a function. Of the remaining 20% of the coding sequences with homology to known proteins or functional domains, only those constituting the Hgr operon and the RulAB homologues were likely to encode host-beneficial phenotypes (Hgr and UV resistance, respectively). Transfer rates of a genetically similar member of the pQBR plasmid family, pQBR11, were assessed on membrane filters under a variety of nutrient conditions and Hg concentrations (36). The transfer coefficients observed indicate that parasitic persistence of these plasmids by horizontal transfer alone is highly unlikely. Outgrowth of plasmid-carrying bacteria, via positive selection for plasmid-borne traits, is known to be important for the persistence of pQBR103 in the phytosphere. Lilley and Bailey (35) demonstrated variations in rates of outgrowth of P. fluorescens SBW25 carrying pQBR103 relative to plasmid-free strains in the phytosphere of sugar beet over the duration of a growing season. The use of different chromosomal selection markers on the plasmid-carrying (kanamycin resistance) and plasmid-free (tetracycline resistance) strains enabled increases in the density of Hgr bacteria to be attributed to outgrowth of the plasmid-carrying inoculum strain rather than horizontal transfer of pQBR103 to the plasmid-free inoculum strain or indigenous bacteria. Early in the growing season, plasmid-carrying strains had reduced rates of outgrowth relative to plasmid-free strains, presumably due to the increased burden of plasmid carriage. However, later on in the growing season, plasmid-carrying strains had increased rates of outgrowth relative to plasmid-free strains. As the environment was pristine pasture with Hg concentrations of 0.032 to 0.092 μg g soil−1 (38), that is, below or equal to those of soils without specific local Hg contamination, the authors attributed this to some seasonably variable, phytosphere-associated conditions selecting for unknown plasmid-encoded traits.

The aim of the present study was to investigate effects of spatially heterogeneous Hg pollution on selection for P. fluorescens SBW25 carrying pQBR103 relative to plasmid-free strains in a spatially structured environment. While sporadic selection, typical of temporally or spatially heterogeneous environments, has been posited as an important determinant of plasmid persistence (19), there have been few attempts to investigate this experimentally. This is due to difficulties in quantifying changes in physical, chemical, and biological conditions in complex natural environments at the microscale and also in predicting the effects of such changes on selection for plasmids (63). In this study, spatially heterogeneous Hg was generated by a novel method, with cellulose fibers imbued with mercuric chloride (HgCl2) sprayed onto a preinoculated membrane filter. The membrane filter surface experimental system was a modified form of that described by Ellis et al. (21). These authors compared the influence of Hg selection on the outgrowth of P. fluorescens SBW25 carrying pQBR103 relative to plasmid-free strains in spatially structured (membrane filter surface) and unstructured (mixed broth) environments. In each environment, both plasmid-carrying and plasmid-free strains were able to increase in frequency from a starting ratio of 1:9 (vol/vol) over a similar range of Hg selection strengths, demonstrating negative frequency-dependent selection for the initially rare phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study, labeled with fluorescent protein markers, were as previously described (21). Briefly, a spontaneous rifampin-resistant mutant of P. fluorescens SBW25, originally isolated from the phyllosphere of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) (1), was labeled by random insertion of a constitutively expressed red fluorescent protein (RFP) cassette (DsRed, Discosoma) into chromosomal DNA following mobilization of the delivery plasmid TTN151 (mini-Tn5-Kmr-rrnBP1::RBSII-dsRed-T0-T1) (59) from Escherichia coli CC118 λpir in a triparental mating with E. coli HB101 (Smr recA thi pro leu hsdRM) carrying the helper plasmid RK600 (Cmr ColE1 oriV RP4 oriT) (21). This strain, designated SBW25R::rfp, was sensitive to Hg (Hgs). The plasmid pQBR103 (425 kb; Tra+ Hgr), originally exogenously isolated from the phytosphere of sugar beet (34), was labeled by random insertion of a constitutively expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP, Aequorea victoria) cassette into plasmid DNA following mobilization of the delivery plasmid pJBA28 (with PA1/O4/O3::gfpmut3b cloned into mini-Tn5 Km) (59) from E. coli CC118 λpir to P. putida UWC1 (Rifr) bearing plasmid pQBR103 in a triparental mating. Marked plasmids were selected by cotransfer of Kmr, Hgr, and GFP to P. putida Mes300 (Nalr) (36). The marked plasmid was transferred back into SBW25R to generate SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp). This strain, designated SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp), was resistant to Hg (Hgr) at a concentration of 0.1 mM mercuric chloride (HgCl2) in standard Pseudomonas selective agar (PSA-Hg; Oxoid, United Kingdom). All strains were stored in glycerol at −80°C and revived by streaking onto Pseudomonas selective agar supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 centrimide, 10 μg ml−1 fucidin, and 50 μg ml−1 cephalosporin (SR0103; Oxoid, United Kingdom) (PSA-CFC), or PSA-Hg where appropriate, prior to each experimental run.

Generation of growth curves in broth.

Liquid monocultures of SBW25R, SBW25R::rfp, SBW25R(pQBR103), and SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp) were obtained by inoculating 5-ml volumes of R2B liquid growth medium with single colonies and incubating them overnight at 28°C in an orbital shaker (180 rpm; Sanyo Gallenkamp, Japan). R2B had the same constituents as R2A (Oxoid, United Kingdom) but without agar, i.e. (in grams per liter), 0.75 peptone, 0.5 yeast extract, 0.5 dextrose, 0.5 starch, 0.3 K2HPO4, 0.3 sodium pyruvate, 0.25 tryptone, and 0.024 MgSO4. Forty-nine-milliliter volumes of R2B, prewarmed to 28°C, were inoculated with 1-ml aliquots of the monocultures and incubated in an orbital shaker. CFU were enumerated every hour for 12 h by removing 1-ml aliquots and performing serial decimal dilutions in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Twenty microliters of each dilution was spotted onto PSA-CFC in duplicate. Plates were incubated overnight at 28°C in a static incubator (LEEC Ltd., United Kingdom), and the microcolonies in each spot were visualized and counted with a light microscope (magnification, ×10; Zeiss, Germany).

Calculation of maximum specific growth rates.

Growth curves were generated by fitting data of CFU as a function of time with the Gompertz model as described by Mackey and Kerridge (42) as follows:

|

(1) |

where a, b, and c are constants, with SigmaPlot version 10 (Systat Software, Inc.).

The maximum specific growth rate, μmax, was then derived by using the equation

|

(2) |

Preparation of membrane filter inoculum.

Liquid monocultures of SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp) (Hgr) and SBW25R::rfp (Hgs) were prepared, and the cells were harvested and washed as previously described (21). The cells were resuspended in 5 ml PBS (Oxoid, United Kingdom), and cell density was standardized by adjusting the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) (GeneQuant pro; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) to approximately 0.5. These suspensions were mixed in a 1:1 (vol/vol) Hgr-to-Hgs ratio, serially diluted in 10- and 2-fold steps in PBS (to approximately 2 × 104 CFU ml−1), and then used to inoculate membrane filters.

CFU of Hgr and Hgs bacteria in each suspension were enumerated by further serially diluting a subsample 2-, 20-, and 200-fold. A 100-μl volume of each dilution was spread plated onto PSA-CFC in triplicate and incubated at 28°C overnight. Colonies of green (Hgr) and red (Hgs) cells were differentiated and counted by epifluorescence microscopy.

Membrane filter preparation.

Black Isopore polycarbonate membrane filters (0.2-μm pore size, 25-mm diameter; Millipore, United Kingdom) were prewashed in sterile distilled water (SDW). A 5-ml inoculum suspension was evenly deposited onto the membrane surface under negative pressure with a vacuum filter apparatus with a sintered glass support (Whatman, United Kingdom). Membrane filters were incubated on 0.7 R2A (constituents as previously described [21]; Oxoid, United Kingdom) at room temperature (21 to 23°C) for 3 days.

Heterogeneous Hg treatment.

Five grams of carboxymethyl cellulose fibers (25 to 60 μm; Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom) was imbued with 30 ml of either SDW or 1.15 or 7.66 mM HgCl2 to give a final concentration of 0, 1,875 or 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1. Each cellulose mixture was dried (65°C, 48 h) and crushed with a pestle and mortar to separate the fibers. To create randomly distributed foci of Hg, 20 mg of Hg-cellulose fibers was sprayed down a sealed tube with a pressurized container (Invertible Air Duster; Viking, The Netherlands) onto a preinoculated membrane filter supported on 0.7 R2A within 3 h of inoculation (Fig. 1). A new container was used for each experimental run to ensure that the pressure of the aerosol was equivalent. The tube was washed with SDW and 70% ethanol between applications. Each treatment was applied in triplicate.

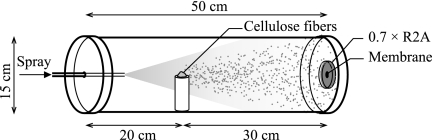

FIG. 1.

Schematic showing the apparatus used to apply cellulose fibers imbued with HgCl2 onto a black Isopore polycarbonate membrane filter (0.2-μm pore size, 25-mm diameter; Millipore, United Kingdom), preinoculated with Hgr and Hgs bacteria and supported on 0.7 R2A (Oxoid, United Kingdom). A pressurized container (Invertible Air Duster; Viking, The Netherlands) was used to atomize and direct fibers toward the membrane surface.

Uniform Hg treatment.

0.7 R2A was supplemented with HgCl2 stock to give a final concentration of 0, 2.5, 5, or 7.5 μM. Each treatment was applied in triplicate.

Epifluorescence microscopy.

After 3 days of incubation, the spatial distribution of green (Hgr) and red (Hgs) colonies on membrane filters was assessed with an Eclipse E600 microscope fitted with a 100-W mercury lamp and two fluorescence cubes, i.e., (i) fluorescein isothiocyanate for visualizing GFP (excitation filter, 465 to 495 nm; dichroic mirror, 505 nm; barrier filter, 515 to 555 nm) and (ii) TRITC for visualizing RFP (excitation filter, 510 to 560 nm; dichroic mirror, 575 nm; barrier filter, 590 nm). The lenses were Nikon Plan Fluor lenses (magnification, ×100/1.3 [oil]); magnification, ×40/0.75; magnification, ×20/0.5; magnification, ×10/0.3). Images of a field of view (FOV; 1.07 mm2, equivalent to 0.22% of the total membrane area) were captured sequentially with each of the two fluorescence cubes with an 8-bit 1394 ORCA-285 camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Japan) and shutters (Ludl Electronic Products) controlled by Simple PCI 6 imaging software (Compix Inc. Imaging Systems).

For uniform Hg treatment membranes, images of at least 10 FOVs per membrane, chosen at random, were captured. For heterogeneous Hg treatment membranes, images of at least 10 FOVs per membrane were captured such that when a cellulose fiber was at the center of the FOV, no other fibers could be seen (Fig. 2).

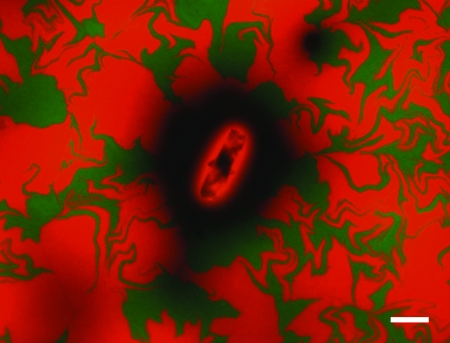

FIG. 2.

Epifluorescence microscope image of a field of an FOV of a membrane filter showing a single cellulose fiber imbued with 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1 surrounded by green (Hgr) and red (Hgs) colonies and with areas with no bacterial cover appearing as black. The membrane was inoculated with 1.13 × 105 bacterial cells at a 5:4 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio and then sprayed with 20 mg Hg-cellulose fibers. The contrast and color balance of the image were changed with Simple PCI 6 imaging software (Compix Inc. Imaging Systems) and Adobe Photoshop CS2 (Adobe Systems Inc.). Scale bar represents 100 μm.

Calculation of area of membrane filter occupied by bacteria.

The threshold intensity function (Simple PCI Core Getting Started Guide version 6.2, http://www.cimaging.net/pdfs/60/guides/SimplePCI.pdf) in the Simple PCI 6 imaging software (Compix Inc. Imaging Systems) was used to measure the total area occupied by green colonies ( ) and red colonies (

) and red colonies ( ) and any black areas without bacterial cover in FOVs. The area of each FOV occupied by Hgr relative to Hgs,

) and any black areas without bacterial cover in FOVs. The area of each FOV occupied by Hgr relative to Hgs,  , was therefore

, was therefore

|

(3) |

Calculation of generations undergone by bacterial populations.

After epifluorescence microscopy, membrane filters were vortexed for 30 s in 1 ml PBS. Membrane filters were removed, and the resultant suspension was serially diluted in 10-fold steps. Twenty microliters of each of the 102-fold to 109-fold dilutions were spotted onto PSA-CFC in duplicate and incubated at 28°C overnight. Microcolonies of green (Hgr) and red (Hgs) cells were counted and differentiated by epifluorescence microscopy. The average number of generations, n, undergone by Hgr and Hgs populations over the 3-day incubation period were approximated by using the equation

|

(4) |

where Nt is the number of Hgr or Hgs cells at the end of the incubation period and N0 is the number of Hgr or Hgs cells at the beginning of the incubation period. Values of n are an approximation, as the calculation does not take cell death during the incubation period into account. The average relative fitness of Hgr populations,  , on whole membrane filters was therefore determined by the equation

, on whole membrane filters was therefore determined by the equation

|

(5) |

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests, including Bartlett's test for homogeneity of variances, normal probability plots for verification of normality of error, and General Linear Model procedures, were calculated with Minitab version 15 (Minitab Ltd., United Kingdom). Response variables were either the area of the FOV occupied by Hgr relative to Hgs,  , (equation 3) or the average relative fitness of Hgr populations,

, (equation 3) or the average relative fitness of Hgr populations,  (equation 5). Data points where values of

(equation 5). Data points where values of  or

or  were equal to 0 (three FOVs only) were excluded from the analysis. All response variable data were log10 transformed, and where necessary, outliers with large standardized residuals were excluded from the analysis to ensure homogeneity of variances.

were equal to 0 (three FOVs only) were excluded from the analysis. All response variable data were log10 transformed, and where necessary, outliers with large standardized residuals were excluded from the analysis to ensure homogeneity of variances.

Statistical tests for trends in  or

or  with Hg concentration (continuous) where the starting Hgr-to-Hgs ratios of bacteria were 1:1 were performed separately for uniform and heterogeneous Hg treatments. Data were pooled from two experimental runs, with freshly prepared bacterial inocula used in each, to give a total of either four or five membrane replicates per treatment. There were small differences in the starting ratios of Hgr to Hgs bacteria between the two experimental runs and therefore the run (categorical, random) was included as a variable where it had a significant effect. A test to check for significant differences between membrane filter replicates in

with Hg concentration (continuous) where the starting Hgr-to-Hgs ratios of bacteria were 1:1 were performed separately for uniform and heterogeneous Hg treatments. Data were pooled from two experimental runs, with freshly prepared bacterial inocula used in each, to give a total of either four or five membrane replicates per treatment. There were small differences in the starting ratios of Hgr to Hgs bacteria between the two experimental runs and therefore the run (categorical, random) was included as a variable where it had a significant effect. A test to check for significant differences between membrane filter replicates in  was also performed by designating the Hg concentration (categorical), membrane (random, categorical, nested within Hg concentration), and run (random, categorical) as explanatory variables. The membrane was found to have a significant effect on

was also performed by designating the Hg concentration (categorical), membrane (random, categorical, nested within Hg concentration), and run (random, categorical) as explanatory variables. The membrane was found to have a significant effect on  (for uniform Hg, F7,167 = 3.25, P = 0.003; for heterogeneous Hg, F6,176 = 3.50, P = 0.003), but in all tests the effect of the Hg concentration remained significant when differences between membrane replicates had been taken into account (for uniform Hg, F3,167 = 507.04, P < 0.001; for heterogeneous Hg, F2,176 = 19.89, P = 0.002).

(for uniform Hg, F7,167 = 3.25, P = 0.003; for heterogeneous Hg, F6,176 = 3.50, P = 0.003), but in all tests the effect of the Hg concentration remained significant when differences between membrane replicates had been taken into account (for uniform Hg, F3,167 = 507.04, P < 0.001; for heterogeneous Hg, F2,176 = 19.89, P = 0.002).

A test for an interaction effect between the Hg concentration (categorical) and the starting ratio (categorical) on  was also performed for data from a single experimental run with three membrane replicates per treatment with a single heterogeneous Hg concentration and a no-Hg control and different starting ratios of bacteria.

was also performed for data from a single experimental run with three membrane replicates per treatment with a single heterogeneous Hg concentration and a no-Hg control and different starting ratios of bacteria.

MATH assay.

The microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons (MATH) assay, a standard assay for measuring cell surface hydrophobicity, was carried out on SBW25R, SBW25R::rfp, SBW25R(pQBR103), and SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp) according to a previously described protocol (51). Briefly, cells were cultured, harvested, washed, and resuspended in PBS and the cell density was standardized by adjusting the OD600 to approximately 0.5. The exact absorbance was recorded. A 1.5-ml suspension of each was vortexed with 0, 200, 400, or 600 μl n-hexadecane (99%; Lancaster Synthesis, United Kingdom) for 1 min in a 30-ml glass bijou (which had been acid washed by being left to stand in 1% [wt/vol] nitric acid [ARISTAR; VWR, United Kingdom] overnight, rinsed three times in SDW, and autoclaved). The resultant suspension was allowed to stand in an upright position for 1 h. The absorbance of the liquid phase was measured by determining the OD600, and the reduction in absorbance from that of the initial suspension was used to calculate the proportion of cells adhering to hexadecane. Each treatment was performed in duplicate.

RESULTS

Spraying cellulose does not impede the formation of nearly confluent lawns of bacteria on membrane filters.

The 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio bacterial suspensions used to inoculate membrane filters in the two experimental runs contained means (± standard error [SE]) of 1.14 × 105 (± 4.95 × 103) and 1.13 × 105 (± 7.67 × 103) cells in Hgr-to-Hgs bacterial ratios of approximately 7:3 and 5:4, respectively. After 3 days of incubation, nearly confluent lawns of bacteria comprising clearly delineated, contiguous red (Hgs) and green (Hgr) colonies covered the membranes. There were small areas without bacterial cover, seen as black under the epifluorescence microscope. The larger examples of these areas were also visible to the naked eye as gaps in the lawn and could therefore be identified as areas without bacterial cover rather than segregant bacteria. Moreover, no colonies of segregant bacteria (i.e., cells that fluoresced neither red nor green) were observed in viable cell counts during the experiment. Transconjugants occupied a negligible area of the membrane surface. At the magnifications used to capture images, transconjugants (i.e., cells that fluoresced both red and green and appeared as orange in overlay epifluorescence microscope images) at the boundaries of Hgr and Hgs colonies were not resolved. At this time, total cell numbers on membranes in the two experimental runs were 5.78 × 109 (± 6.80 × 108) and 1.05 × 1010 (± 2.34 × 109), respectively, corresponding to an average number of generations undergone by whole membrane communities of 15.54 (± 0.16) and 16.24 (± 0.16). Two no-Hg control treatments were included in each experimental run, one with no cellulose treatment at all and the other with 20 mg of cellulose imbued with SDW sprayed onto membranes as described above. There were no significant differences in values of  between the two control treatments when differences between the two experimental runs had been taken into account (F1,103 = 0.00, P = 0.968). Average proportional areas without bacterial cover in FOVs were also similar between the two control treatments (Table 1). Any differences in community structure in Hg cellulose treatments were therefore a result of the Hg itself rather than any physical effect of spraying the cellulose.

between the two control treatments when differences between the two experimental runs had been taken into account (F1,103 = 0.00, P = 0.968). Average proportional areas without bacterial cover in FOVs were also similar between the two control treatments (Table 1). Any differences in community structure in Hg cellulose treatments were therefore a result of the Hg itself rather than any physical effect of spraying the cellulose.

TABLE 1.

Average proportional areas of FOVs without bacterial cover on membrane filters inoculated with approximately 105 bacteria at a 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio and incubated for 3 days

| Hg treatmenta | Mean % of area without bacterial cover (± SE) |

|---|---|

| Uniform (μM concn) | |

| 0.0 | 0.33 (0.19) |

| 2.5 | 0.01 (0.01) |

| 5.0 | 0.01 (0.01) |

| 7.5 | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Heterogeneous (μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1) | |

| 0.0 | 0.28 (0.03) |

| 1,875.0 | 0.55 (0.20) |

| 12,500.0 | 5.19 (1.40) |

Heterogeneous Hg treatments (cellulose fibers imbued with HgCl2 and sprayed onto membranes) resulted in greater areas without bacterial cover than did control and uniform Hg treatments (HgCl2 added to agar).

Plasmid carriage confers a burden under Hg-free conditions.

The Gompertz growth model closely fitted the data of CFU in broth as a function of time, with R2 values of 0.93 to 0.99 for each of the four strains (data not shown). The maximum specific growth rates, μmax, of the plasmid-carrying strain, SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp), and its unlabeled counterpart, SBW25R(pQBR103), were (in units of 108 CFU ml h−1) 3.25 and 3.55, and those of the plasmid-free strain, SBW25R::rfp, and its unlabeled counterpart, SBW25R, were 4.95 and 4.67, respectively. Growth rates of plasmid-carrying strains relative to plasmid-free strains were therefore between 0.66 and 0.76, demonstrating that plasmid carriage conferred a substantial burden under these conditions. Values of μmax did not differ markedly between labeled and unlabeled strains, indicating that carriage and expression of the RFP and GFP cassettes conferred little or no burden under these conditions.

When SBW25R::rfp and SBW25R (pQBR103::gfp) were inoculated onto membrane filters in a 1:1 ratio in the absence of Hg, the mean (± SE) area of FOVs occupied by Hgr bacteria was 24.71% (± 2.36%), compared to the 74.42% (± 2.36%) occupied by Hgs bacteria (Fig. 3a, pooled results from the two control treatments, 0 μM Hg and 0 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1), such that the area occupied by Hgr bacteria relative to that occupied by Hgs bacteria,  , was 0.33. At this time, the mean average number of generations (± SE) undergone by Hgr populations was 13.65 (± 0.47), compared to the 17.28 (± 0.30) of Hgs populations (Fig. 3b, pooled results from the two control treatments, 0 μM Hg and 0 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1), such that the fitness of Hgr relative to Hgs populations,

, was 0.33. At this time, the mean average number of generations (± SE) undergone by Hgr populations was 13.65 (± 0.47), compared to the 17.28 (± 0.30) of Hgs populations (Fig. 3b, pooled results from the two control treatments, 0 μM Hg and 0 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1), such that the fitness of Hgr relative to Hgs populations,  , was 0.78. Plasmid carriage therefore conferred burdens in both spatially structured and well-mixed environments.

, was 0.78. Plasmid carriage therefore conferred burdens in both spatially structured and well-mixed environments.

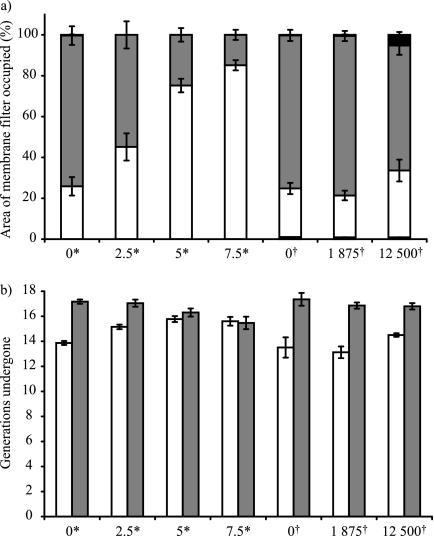

FIG. 3.

Proportional area of FOVs occupied by Hgs (gray) and Hgr (open) bacteria (a) and average number of generations undergone by Hgs and Hgr populations on whole membranes (b) 3 days after inoculation with approximately 105 bacteria at a 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio. At the scale of the FOV, there is an increase in positive selection for Hgr bacteria with the Hg concentration in both uniform (*, HgCl2 added to agar [μM]) and heterogeneous (†, cellulose fibers imbued with HgCl2 [μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1]) Hg treatments. Higher Hg concentrations also result in increased areas without bacterial cover (black) in heterogeneous Hg treatments only. At the scale of the whole membrane, there is an increase in positive selection for Hgr bacteria with the Hg concentration in uniform Hg treatments but not in heterogeneous treatments. Error bars indicate the standard error of four or five replicate membranes per treatment.

Plasmid carriage confers a constant benefit under spatially uniform Hg and a sporadic benefit under spatially heterogeneous Hg.

When membrane filters were inoculated with bacteria in a 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio, the FOV area of Hgr relative to Hgs,  , increased with the Hg concentration in both uniform and heterogeneous Hg treatments (Fig. 3a; Table 2). A similar trend was apparent for the relative fitness of Hgr populations,

, increased with the Hg concentration in both uniform and heterogeneous Hg treatments (Fig. 3a; Table 2). A similar trend was apparent for the relative fitness of Hgr populations,  , with the Hg concentration in uniform Hg treatments but not in heterogeneous Hg treatments (Fig. 3b; Table 2). These differences are most likely due to heterogeneous Hg producing only localized Hg selection effects, with large areas of membranes unaffected, such that positive selection for Hgr bacteria was not apparent at the population level. In heterogeneous Hg treatments,

, with the Hg concentration in uniform Hg treatments but not in heterogeneous Hg treatments (Fig. 3b; Table 2). These differences are most likely due to heterogeneous Hg producing only localized Hg selection effects, with large areas of membranes unaffected, such that positive selection for Hgr bacteria was not apparent at the population level. In heterogeneous Hg treatments,  was calculated for bacteria in FOVs (1.07 mm2) centered on foci of Hg whereas

was calculated for bacteria in FOVs (1.07 mm2) centered on foci of Hg whereas  was calculated for whole membrane (490.87 mm2) populations. There was a mean (± SE) of 146.34 (± 23.70) cellulose foci per membrane filter, covering 0.28% (± 0.06%) of the total membrane area, after a single 20-mg application (estimated from an analysis of 10 randomly chosen FOVs per membrane filter for 15 replicate membrane filters). At this density, more than 75% of the total membrane area would be occupied by bacteria that were more than 0.5 mm from a cellulose fiber (assuming nonoverlapping circles with a radius of 0.5 mm around each cellulose fiber).

was calculated for whole membrane (490.87 mm2) populations. There was a mean (± SE) of 146.34 (± 23.70) cellulose foci per membrane filter, covering 0.28% (± 0.06%) of the total membrane area, after a single 20-mg application (estimated from an analysis of 10 randomly chosen FOVs per membrane filter for 15 replicate membrane filters). At this density, more than 75% of the total membrane area would be occupied by bacteria that were more than 0.5 mm from a cellulose fiber (assuming nonoverlapping circles with a radius of 0.5 mm around each cellulose fiber).

TABLE 2.

Statistical analysis of data by General Linear Model in Minitab version 15 (Minitab Ltd., United Kingdom)a

| Response variable | Hg treatment | Starting Hgr-to-Hgs ratio(s) | Explanatory variable(s) | No. of outliers removed | Explanatory variable, F statistic (P valueb) | Slope (m), T statistic (P valueb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Uniform (0, 2.5, 5, 7.5)c | 1:1 | Hgd + rune | 17 | Hg, F1,170 = 3,669.07 (< 0.001)h | 0.45, 60.57 (< 0.001)h |

| Run, F1,170 = 574.55 (< 0.001)h | ||||||

|

Heterogeneous (0, 1,875, 12,500)f | 1:1 | Hgd + rune | 30 | Hg, F1,163 = 28.47 (< 0.001)h | 0.06, 5.34 (< 0.001)h |

| Run, F1,163 = 142.53 (< 0.001)h | ||||||

|

Uniform (0, 2.5, 5, 7.5)c | 1:1 | Hgd | 0 | Hg, F1,18 = 114.86 (< 0.001)h | 0.03, 10.72 (< 0.001)h |

|

Heterogeneous (0, 1,875, 12,500)f | 1:1 | Hgd | 0 | Hg, F1,14 = 3.83 (0.070) | 0.02, 1.96 (0.070) |

|

Heterogeneous (0, 9,375)f | 1:1, 9:1, 12:1, 16:1 | Hgg × ratiog | 21 | Hg, F1,208 = 73.08 (< 0.001)h | |

| Ratio, F3,208 = 428.51 (< 0.001)h | ||||||

| Interaction, F3,208 = 3.93 (0.009)h |

Response variable data were log10 transformed, and where necessary, outliers with large standardized residuals were removed to ensure homogeneity of variances. For a starting Hgr-to-Hgs bacterial ratio of 1:1 and uniform or heterogeneous Hg treatments, data were pooled from two experimental runs with freshly prepared bacterial inocula used in each. The run was included as a variable when it had a significant effect. The area of the FOV occupied by Hgr relative to Hgs bacteria,  , increased with the Hg concentration for both uniform and heterogeneous Hg treatments. The relative fitness of Hgr populations,

, increased with the Hg concentration for both uniform and heterogeneous Hg treatments. The relative fitness of Hgr populations,  , increased with the Hg concentration for uniform Hg but not heterogeneous Hg treatments. There was an interaction effect between different starting ratios of bacteria and the Hg treatment on

, increased with the Hg concentration for uniform Hg but not heterogeneous Hg treatments. There was an interaction effect between different starting ratios of bacteria and the Hg treatment on  .

.

Given for continuous explanatory variables only.

Micromolar concentrations.

Continuous.

Random, categorical.

Micrograms of HgCl2 per gram of cellulose.

Categorical.

Significant at the 1% level.

In the heterogeneous Hg treatment with the highest concentration of Hg, 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1, there was a mean (± SE) area without bacterial cover of 5.19% (± 1.40%) of the total FOV area (Table 1). This was almost 20-fold higher than for control treatments and almost 10-fold higher than for the other heterogeneous Hg treatment, 1,875 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1. This indicates that 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1 resulted in some areas of the membrane that were so highly Hg impacted that the growth of even Hgr cells was impaired.

Taken together, these findings suggest that there were changes from positive to negative selection for Hgr bacteria over distances of a few hundred micrometers from Hg-cellulose foci.

Values of  were also found to differ significantly between the two experimental runs, although values of

were also found to differ significantly between the two experimental runs, although values of  did not (Table 2). This can be attributed to the small difference in the starting ratios of bacteria (7:3 and 5:4 Hgr-to-Hgs ratios) in the inoculum used in each run. The calculation of

did not (Table 2). This can be attributed to the small difference in the starting ratios of bacteria (7:3 and 5:4 Hgr-to-Hgs ratios) in the inoculum used in each run. The calculation of  (equation 5) from the number of generations, n (equation 4), has the effect of normalizing any small differences in starting ratios, whereas the calculation of

(equation 5) from the number of generations, n (equation 4), has the effect of normalizing any small differences in starting ratios, whereas the calculation of  (equation 3) does not.

(equation 3) does not.

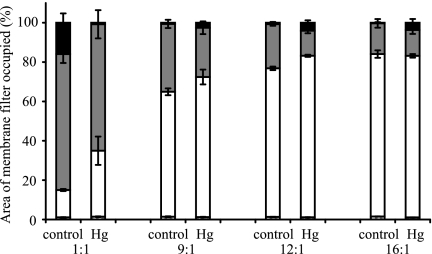

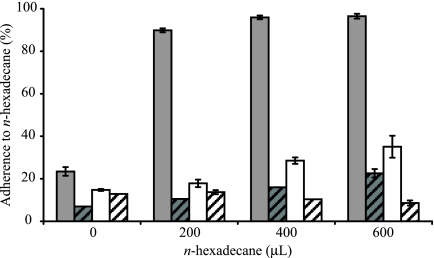

The benefit of plasmid carriage is negative frequency dependent under spatially heterogeneous Hg.

The experiment was repeated with either a heterogeneous Hg treatment, 9,375 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1, or a no-Hg control treatment and a variety of starting ratios of Hgr to Hgs bacteria. Pilot experiments indicated that treatments with a lower than 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio resulted in few Hgr colonies, many of which were too small to be captured by the image analysis software (data not shown), and so these treatments were not included in the final experiment. Actual inocula contained a mean (± SE) of 1.48 × 105 (± 7.38 × 104) bacteria in Hgr-to-Hgs ratios of approximately 1:1, 9:1, 12:1, and 16:1 (vol/vol). The magnitude of the change in  between the no-Hg control treatment and the heterogeneous Hg treatment differed according to the proportion of Hgr bacteria in the inoculum (Table 2), with a greater increase in positive selection for Hgr bacteria when Hgr cells were initially rare (Fig. 4). This indicates that negative frequency-dependent selection for the plasmid-carrying bacteria, previously demonstrated in spatially structured and unstructured environments under uniform Hg conditions by Ellis et al. (21), also occurs when Hg is heterogeneously distributed in spatially structured environments.

between the no-Hg control treatment and the heterogeneous Hg treatment differed according to the proportion of Hgr bacteria in the inoculum (Table 2), with a greater increase in positive selection for Hgr bacteria when Hgr cells were initially rare (Fig. 4). This indicates that negative frequency-dependent selection for the plasmid-carrying bacteria, previously demonstrated in spatially structured and unstructured environments under uniform Hg conditions by Ellis et al. (21), also occurs when Hg is heterogeneously distributed in spatially structured environments.

FIG. 4.

The mean proportional area of FOVs occupied by Hgs (gray) bacteria decreases and that of Hgr (open) bacteria increases with a heterogeneous Hg treatment (9,375 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1) compared to a no-Hg control treatment. The magnitude of this effect is greater when Hgr bacteria are initially comparatively rare (1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio) than when they are common (16:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio), indicating negative-frequency-dependent selection for Hgr bacteria. The areas of FOVs without bacterial cover (black) are also shown. Error bars indicate the standard error of three replicate membranes per treatment.

Carriage of the RFP cassette impairs the ability of SBW25R::rfp to grow across a membrane filter surface.

There were unexpectedly large areas without bacterial cover in treatments with low final Hgr-to-Hgs ratios. For example, when membrane filters were inoculated with bacteria in a 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio, the no-Hg control treatments resulted in approximately 10-fold higher percentage areas of FOV without bacterial cover than uniform Hg treatments of 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μM HgCl2 (Table 1). Similarly, when membrane filters were inoculated with bacteria at an Hgr-to-Hgs ratio of 1:1, 9:1, 12:1, or 16:1, the no-Hg control 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio treatment resulted in a mean (± SE) area without bacterial cover of 16.0% (± 4.71%), more than 20-fold larger than for all of the other no-Hg control treatments (Fig. 4). These results are unexpected, as bacteria in no-Hg control 1:1 Hgr-to-Hgs ratio treatments would be expected to have a faster average growth rate than bacteria in all of the Hg treatments and no-Hg control treatments with the higher Hgr-to-Hgs ratios. Hgs cells have higher maximum specific growth rates than Hgr cells, and also, Hg is known to limit the growth of even Hgr bacteria by reducing the growth rate (5), increasing the lag time (5, 26), and causing cell death (7). One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the random insertion of the RFP cassette into the chromosomal DNA of SBW25R has caused a loss of function in a gene important for determining cell surface properties, thereby adversely affecting the ability of the labeled strain to grow across surfaces. While the value of μmax for SBW25R::rfp was not appreciably different from that of the unlabeled parent strain in mixed broth, SBW25R::rfp was found to have far higher cell surface hydrophobicity than SBW25R or, indeed, SBW25R(pQBR103) and SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp) (Fig. 5). It has long been recognized that bacteria with hydrophobic cell surfaces tend to adhere to one another, resulting in the formation of clumps (57). We propose that this is the cause of the larger areas without bacterial cover on membranes with low final Hgr-to-Hgs ratios.

FIG. 5.

Fluorescently labeled SBW25R::rfp cells (gray) exhibit more-than-threefold greater adherence to hexadecane than do wild-type SBW25R cells (gray, oblique lines), fluorescently labeled SBW25R(pQBR103::gfp) cells (open), and wild-type SBW25R(pQBR103) cells (open, oblique lines), which is indicative of higher cell surface hydrophobicity.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the effects of spatially heterogeneous Hg on the distribution of an Hgr plasmid in a community of pseudomonads colonizing a surface were investigated with a model experimental system. Hg was chosen as the agent of selection as it is a priority pollutant (22) and bacterial resistance mechanisms, particularly the enzymatic reduction of Hg(II) to Hg(0), are well characterized (44). Also, Hg is heterogeneously distributed in natural environments such as soil because of its differential binding to various soil components, such as organic matter and clay minerals (25). Cellulose fibers were used as carriers of Hg because, as a major component of plant cell walls, cellulose is likely to be abundant in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere environments from which P. fluorescens has been isolated. Indeed, cellulose is the matrix component of biofilms produced by P. fluorescens and other pseudomonads (61).

There was evidence of change in selection for Hgr bacteria from positive to negative over distances of a few hundred micrometers from Hg foci in heterogeneous Hg treatments. This is comparable to the distances over which selection changes in heterogeneous natural environments, such as soil. Ranjard et al. (49) reported differences in the strength of positive selection for Hgr strains between different-size fractions of soil aggregates in microcosms spiked with HgCl2 and incubated for 30 days. In the largest fraction, 250 to 2,000 μm, numbers of Hgr bacteria increased 580-fold from prespiking levels, whereas in the smallest fraction, <2 μm, numbers of Hgr bacteria increased only 5-fold. The authors attributed this to increased bioavailability of Hg in the larger fractions due to a combination of physical and chemical factors. Large pore diameters, prevalent around large fraction aggregates, facilitate the circulation of solutes, including free Hg ions. Also, the reactive organic matter and clay minerals that dominate small fractions strongly bind Hg, reducing its bioavailability. Ranjard et al. spiked microcosms with 50 μM HgCl2, equivalent to 10 μg Hg g soil−1. In the present study, the uniform Hg treatment with the highest Hg concentration was 7.5 μM HgCl2, equivalent to 1.5 μg Hg g agar−1. However, it is not possible to use these values to accurately compare selection strengths as the physical structures and chemical properties of soils and agar may have large and dissimilar effects on Hg bioavailability (8, 23). The spiking treatment of Ranjard et al. and the heterogeneous Hg treatment with the highest Hg concentration in the present study, 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1, are similar in that they both resulted in variable selection conditions across space. However, Ranjard et al. demonstrated global positive selection for Hgr bacteria, as there was some increase in the numbers of Hgr bacteria in all size fractions of soil whereas in the present study, there was only localized positive selection for Hgr bacteria in the 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1 treatment. Therefore, the 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1 treatment may be considered to have resulted in an overall lower degree of selection than the 50 μM HgCl2 spiking treatment of Ranjard et al.

The failure to detect positive selection for Hgr bacteria at the population level in the 12,500 μg HgCl2 g cellulose−1 treatment emphasizes the importance of using an analysis method appropriate for the scale over which the pertinent parameters are likely to vary. This is particularly relevant for the design of environmental surveys of bacterial diversity in complex environments such as soil. Ramette and Tiedje (48) recently reported difficulties in quantifying the effect of environmental heterogeneity on species abundance and diversity of the Burkholderia cepacia complex in the rhizosphere. Much of the biotic variation was left unexplained by either the environmental variables measured (e.g., pH, organic matter, plant species present) or spatial distance. The authors attributed this to either failure to fully delineate the environmental variables that shape the microbial community structure or to processes of random drift (or some combination of both). It may be that the sampling scheme used by Ramette and Tiedje (four pooled subsamples from a 5- to 20-cm soil depth for physical and chemical variables and 1-g samples from a complete root system for biological variables) was not at a sufficiently fine scale to adequately describe the variation in selection pressures responsible for shaping community structure.

In the present study, there was evidence that the labeling of SBW25R with an RFP cassette by random chromosomal insertion resulted in increased cellular hydrophobicity, which may have impaired the ability of the labeled strain to form a confluent lawn on membrane surfaces. Similar hydrophobic phenotypes have been demonstrated in nodulation-deficient isolates of Bradyrhizobium japonicum following random mutagenesis by Tn5 (55). Nodulation-deficient mutant B. japonicum JS314 cells showed rapid and almost complete adherence to hexadecane when subjected to the MATH assay, whereas wild-type parental B. japonicum cells remained unaffected (45). JS314 exhibited no observable differences in colony morphology, growth rate, or turbidity from the wild-type parental strain (56). Similarly, the growth rate of SBW25R::rfp in broth did not differ markedly from that of the parental strain. Also, no differences in colony morphology or turbidity were observed during the course of the present study. These findings serve as a reminder that labeling strains with marker genes for monitoring purposes may have subtle adverse effects on cellular physiology that may not be immediately apparent when selecting stable transfected cells. Caution is therefore required in using the proportional area of membrane covered by Hgs and Hgr as a measurement of fitness. However, only those membranes with large (>70%) average areas of FOVs occupied by Hgs bacteria appeared to be substantially affected by this phenomenon. The use of a secondary measurement of fitness,  , which was apparently unaffected coupled with appropriate control treatments also ensured that it was possible to delineate effects of Hg from effects of carriage of the RFP cassette.

, which was apparently unaffected coupled with appropriate control treatments also ensured that it was possible to delineate effects of Hg from effects of carriage of the RFP cassette.

The negative frequency-dependent selection for Hgr bacteria, first demonstrated by Ellis et al. (21) and also in the present study, may be explained in terms of local dynamics of the community colonizing the membrane surface over the 3-day incubation period. In an Hg-impacted environment, Hgr bacteria have a growth rate advantage over Hgs bacteria. When Hgr cells are initially rare, the relative advantage of being Hgr is high as the majority of competitors are Hgs and therefore slower growing. However, when Hgr cells are initially common, the majority of competitors are Hgr and so the relative advantage of being Hgr is low. These effects are compounded by the rate of Hg degradation, which will be higher when Hgr cells are common. As the Hg impact decreases over time, so does the growth rate advantage of being Hgr. In the present study, negative frequency-dependent selection for Hgr bacteria was demonstrated to occur under heterogeneous Hg conditions. This suggests that plasmid-carrying and plasmid-free bacteria may be able to coexist in environments where there is either spatially or temporally heterogeneous selection pressure. This finding supports Eberhard's (19) theory that plasmids are able to maintain discontinuous distributions in bacterial communities as a result of sporadic selection. The next challenge is to investigate the range of selection strengths and distributions at which coexistence is possible over longer periods of time and in the face of other realistic ecological variables, such as periodic extrinsic mortality events (6). This type of investigation would require numerous iterations under different conditions and is therefore well suited to a mathematical approach. An appropriate computational tool for this is a spatially explicit, individual-based model, such as the one recently developed by Krone et al. (31), to investigate plasmid loss and horizontal transfer. Factors found to be relevant in the present study will therefore be used to parameterize and validate a similar model that incorporates spatially heterogeneous selection, as well as spatial structure.

Acknowledgments

F.R.S. is funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council.

We are grateful to Tracey Timms-Wilson for the kind donation of strains, Rosie Hails for advice regarding statistical analyses, and four anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey, M. J., A. K. Lilley, I. P. Thompson, P. B. Rainey, and R. J. Ellis. 1995. Site directed chromosomal marking of a fluorescent pseudomonad isolated from the phytosphere of sugar beet: stability and potential for marker gene transfer. Mol. Ecol. 4:755-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker, J. M., T. Parkin, C. H. Nakatsu, J. D. Wilbur, and A. Konopka. 2006. Bacterial activity, community structure, and centimeter-scale spatial heterogeneity in contaminated soil. Microb. Ecol. 51:220-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergstrom, C. T., M. Lipsitch, and B. R. Levin. 2000. Natural selection, infectious transfer and the existence conditions for bacterial plasmids. Genetics 155:1505-1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjorkman, J., and D. I. Andersson. 2000. The cost of antibiotic resistance from a bacterial perspective. Drug Resist. Updates 3:237-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brim, H., S. C. McFarlan, J. K. Fredrickson, K. W. Minton, M. Zhai, L. P. Wackett, and M. J. Daly. 2000. Engineering Deinococcus radiodurans for metal remediation in radioactive mixed waste environments. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckling, A., R. Kassen, G. Bell, and P. B. Rainey. 2000. Disturbance and diversity in experimental microcosms. Nature 408:961-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, J. S., Y. P. Chao, and W. S. Law. 1998. Repeated fed-batch operations for microbial detoxification of mercury using wild-type and recombinant mercury-resistant bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 64:219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, J. S., J. Hong, O. A. Ogunseitan, and B. H. Olson. 1993. Interaction of mercuric ions with the bacterial growth medium and its effects on enzymatic reduction of mercury. Biotechnol. Prog. 9:526-532. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen, B. B., J. A. J. Haagensen, A. Heydorn, and S. Molin. 2002. Metabolic commensalism and competition in a two-species microbial consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2495-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corchero, J. L., and A. Villaverde. 1998. Plasmid maintenance in Escherichia coli recombinant cultures is dramatically, steadily and specifically influenced by features of the encoded proteins. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 58:625-632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costerton, J. W., Z. Lewandowski, D. DeBeer, D. Caldwell, D. Korber, and G. James. 1994. Biofilms, the customized microniche. J. Bacteriol. 176:2137-2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlberg, C., C. Linberg, V. L. Torsvik, and M. Hermansson. 1997. Conjugative plasmids isolated from bacteria in marine environments show various degrees of homology to each other and are not closely related to well-characterized plasmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4692-4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davey, M. E., and G. A. O'Toole. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:847-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison, J. 1999. Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment. Plasmid 42:73-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz Ricci, J. C., and M. E. Hernández. 2000. Plasmid effects on Escherichia coli metabolism. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 20:79-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doolittle, W. F. 1999. Phylogenetic classification and the universal tree. Science 284:2124-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Droge, M., A. Puhler, and W. Selbitschka. 1999. Horizontal gene transfer among bacteria in terrestrial and aquatic habitats as assessed by microcosm and field studies. Biol. Fertil. Soils 29:221-245. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dronen, A. K., V. Torsvik, and E. M. Top. 1999. Comparison of the plasmid types obtained by two distantly related recipients in biparental exogenous plasmid isolations from soil. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:105-110. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberhard, W. G. 1990. Evolution in bacterial plasmids and levels of selection. Q. Rev. Biol. 65:3-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisen, J. A. 2000. Horizontal gene transfer among microbial genomes: new insights from complete genome analysis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10:606-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis, R. J., A. K. Lilley, S. J. Lacey, D. Murrell, and H. C. J. Godfray. 2007. Frequency-dependent advantages of plasmid carriage by Pseudomonas in homogeneous and spatially structured environments. ISME J. 1:92-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Environmental Protection Agency. 2006. Roadmap for mercury. EPA-HQ-OPPT-2005-0013. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. http://www.epa.gov/mercury/roadmap.htm.

- 23.Giller, K. E., E. Witter, and S. P. McGrath. 1998. Toxicity of heavy metals to microorganisms and microbial processes in agricultural soils: a review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30:1389-1414. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gogarten, J. P., and J. P. Townsend. 2005. Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:679-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grigal, D. F. 2003. Mercury sequestration in forests and peatlands: a review. J. Environ. Qual. 32:393-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen, C. L., G. Zwolinski, D. Martin, and J. W. Williams. 1984. Bacterial removal of mercury from sewage. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 26:1330-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen, S. K., P. B. Rainey, J. A. J. Haagensen, and S. Molin. 2007. Evolution of species interactions in a biofilm community. Nature 445:533-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill, K. E., and E. M. Top. 1998. Gene transfer in soil systems using microcosms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 25:319-329. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill, K. E., A. J. Weightman, and J. C. Fry. 1992. Isolation and screening of plasmids from the epilithon which mobilize recombinant plasmid pD10. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1292-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain, R., M. C. Rivera, J. E. Moore, and J. A. Lake. 2002. Horizontal gene transfer in microbial genome evolution. Theor. Popul. Biol. 61:489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krone, S. M., R. Lu, R. Fox, H. Suzuki, and E. M. Top. 2007. Modelling the spatial dynamics of plasmid transfer and persistence. Microbiology 153:2803-2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurland, C. G., B. Canback, and O. G. Berg. 2003. Horizontal gene transfer: a critical view. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:9658-9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin, B. R. 1993. The accessory genetic elements of bacteria: existence conditions and (co)evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 3:849-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lilley, A. K., and M. J. Bailey. 1997. The acquisition of indigenous plasmids by a genetically marked pseudomonad population colonizing the sugar beet phytosphere is related to local environmental conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1577-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lilley, A. K., and M. J. Bailey. 1997. Impact of plasmid pQBR103 acquisition and carriage on the phytosphere fitness of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25: burden and benefit. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1584-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lilley, A. K., and M. J. Bailey. 2002. The transfer dynamics of Pseudomonas sp. plasmid pQBR11 in biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42:243-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lilley, A. K., M. J. Bailey, M. Barr, K. Kilshaw, T. M. Timms-Wilson, M. J. Day, S. J. Norris, T. H. Jones, and H. C. J. Godfray. 2003. Population dynamics and gene transfer in genetically modified bacteria in a model microcosm. Mol. Ecol. 12:3097-3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lilley, A. K., M. J. Bailey, M. J. Day, and J. C. Fry. 1996. Diversity of mercury resistance plasmids obtained by exogenous isolation from the bacteria of sugar beet in three successive years. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 20:211-227. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lilley, A. K., J. C. Fry, M. J. Day, and M. J. Bailey. 1994. In situ transfer of an exogenously isolated plasmid between Pseudomonas spp. in sugar beet rhizosphere. Microbiology 140:27-33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.López-Amorós, R., J. Vives-Rego, and J. García-Lara. 1997. Exogenous isolation of Hgr plasmids from coastal Mediterranean waters and their effect on growth and survival of Escherichia coli in sea water. Microbios 92:109-122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macarthur, R. H. 1964. Environmental factors affecting bird species diversity. Am. Naturalist 98:387-397. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mackey, B. M., and A. L. Kerridge. 1988. The effect of incubation temperature and inoculum size on growth of salmonellae in minced beef. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 6:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ochman, H., J. G. Lawrence, and E. A. Groisman. 2000. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osborn, A. M., K. D. Bruce, P. Strike, and D. A. Ritchie. 1997. Distribution, diversity and evolution of the bacterial mercury resistance (mer) operon. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 19:239-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park, K. M., and J. S. So. 2000. Altered cell surface hydrophobicity of lipopolysaccharide-deficient mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Microbiol. Methods 41:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pianka, E. R. 1967. On lizard species diversity: North American flatland deserts. Ecology 48:333-351. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rainey, P. B., and M. Travisano. 1998. Adaptive radiation in a heterogeneous environment. Nature 394:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramette, A., and J. M. Tiedje. 2007. Multiscale responses of microbial life to spatial distance and environmental heterogeneity in a patchy ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:2761-2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ranjard, L., S. Nazaret, F. Gourbiere, J. Thioulouse, P. Linet, and A. Richaume. 2000. A soil microscale study to reveal the heterogeneity of Hg(II) impact on indigenous bacteria by quantification of adapted phenotypes and analysis of community DNA fingerprints. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 31:107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rasmussen, L. D., and S. J. Sorensen. 1998. The effect of long-term exposure to mercury on the bacterial community in marine sediment. Curr. Microbiol. 36:291-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg, M. 1984. Bacterial adherence to hydrocarbons: a useful technique for studying cell-surface hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 22:289-295. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneiker, S., M. Keller, M. Droge, E. Lanka, A. Puhler, and W. Selbitschka. 2001. The genetic organization and evolution of the broad host range mercury resistance plasmid pSB102 isolated from a microbial population residing in the rhizosphere of alfalfa. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:5169-5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simonsen, L. 1990. Dynamics of plasmid transfer on surfaces. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1001-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smit, E., A. Wolters, and J. D. van Elsas. 1998. Self-transmissible mercury resistance plasmids with gene-mobilizing capacity in soil bacterial populations: influence of wheat roots and mercury addition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1210-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.So, J. S., A. L. M. Hodgson, R. Haugland, M. Leavitt, Z. Banfalvi, A. J. Nieuwkoop, and G. Stacey. 1987. Transposon-induced symbiotic mutants of Bradyrhizobium japonicum: isolation of two gene regions essential for nodulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 207:15-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stacey, G., J. S. So, L. E. Roth, L. S. K. Bhagya, and R. W. Carlson. 1991. A lipopolysaccharide mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum that uncouples plant from bacterial differentiation. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 4:332-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stanley, S. O., and A. H. Rose. 1967. On clumping of Corynebacterium xerosis as affected by temperature. J. Gen. Microbiol. 48:9-23. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tett, A., A. J. Spiers, L. C. Crossman, D. Ager, L. Ciric, J. M. Dow, J. C. Fry, D. Harris, A. K. Lilley, A. Oliver, J. Parkhill, M. A. Quail, P. B. Rainey, N. J. Saunders, K. Seeger, L. A. S. Snyder, R. Squares, C. M. Thomas, S. L. Turner, X. X. Zhang, D. Field, and M. Bailey. 2007. Sequence-based analysis of pQBR103; a representative of a unique, transfer-proficient mega plasmid resident in the microbial community of sugar beet. ISME J. 1:331-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tolker-Nielsen, T., U. C. Brinch, P. C. Ragas, J. B. Andersen, C. S. Jacobsen, and S. Molin. 2000. Development and dynamics of Pseudomonas sp. biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 182:6482-6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turner, S. L., A. K. Lilley, and M. J. Bailey. 2002. Two dnaB genes are associated with the origin of replication of pQBR55, an exogenously isolated plasmid from the rhizosphere of sugar beet. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ude, S., D. L. Arnold, C. D. Moon, T. Timms-Wilson, and A. J. Spiers. 2006. Biofilm formation and cellulose expression among diverse environmental Pseudomonas isolates. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1997-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Elsas, J. D., J. C. Fry, P. Hirsch, and S. Molin. 2000. Ecology of plasmid transfer and spread, p. 175-206. In C. M. Thomas (ed.), The horizontal gene pool: bacterial plasmids and gene spread. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 63.van Elsas, J. D., S. Turner, and M. J. Bailey. 2003. Horizontal gene transfer in the phytosphere. New Phytol. 157:525-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Viegas, C. A., A. K. Lilley, K. Bruce, and M. J. Bailey. 1997. Description of a novel plasmid replicative origin from a genetically distinct family of conjugative plasmids associated with phytosphere microflora. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 149:121-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu, K. D., P. S. Stewart, F. Xia, C. T. Huang, and G. A. McFeters. 1998. Spatial physiological heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm is determined by oxygen availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4035-4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang, X. X., A. K. Lilley, M. J. Bailey, and P. B. Rainey. 2004. The indigenous Pseudomonas plasmid pQBR103 encodes plant-inducible genes, including three putative helicases. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 51:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou, J. Z., B. C. Xia, D. S. Treves, L. Y. Wu, T. L. Marsh, R. V. O'Neill, A. V. Palumbo, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Spatial and resource factors influencing high microbial diversity in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:326-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]