Abstract

The Sec translocon is a protein-conducting channel that allows polypeptides to be transferred across or integrated into a membrane. Although protein translocation and insertion in Escherichia coli have been studied using only a small set of specific model substrates, it is generally assumed that most secretory proteins and inner membrane proteins use the Sec translocon. Therefore, we have studied the role of the Sec translocon using subproteome analysis of cells depleted of the essential translocon component SecE. The steady-state proteomes and the proteome dynamics were evaluated using one- and two-dimensional gel analysis, followed by mass spectrometry-based protein identification and extensive immunoblotting. The analysis showed that upon SecE depletion (i) secretory proteins aggregated in the cytoplasm and the cytoplasmic σ32 stress response was induced, (ii) the accumulation of outer membrane proteins was reduced, with the exception of OmpA, Pal, and FadL, and (iii) the accumulation of a surprisingly large number of inner membrane proteins appeared to be unaffected or increased. These proteins lacked large translocated domains and/or consisted of only one or two transmembrane segments. Our study suggests that several secretory and inner membrane proteins can use Sec translocon-independent pathways or have superior access to the remaining Sec translocons present in SecE-depleted cells.

The genome of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli harbors around 4,000 open reading frames (6, 9). Around 25% of these open reading frames encode inner membrane proteins, and around 10% encode secretory (i.e., periplasmic and outer membrane) proteins (17, 54). It is generally assumed that the Sec pathway is the major route for protein translocation across and insertion into the inner membrane of E. coli (37, 49). The targeting of secretory proteins to the Sec translocon is mostly posttranslational and can be facilitated by the cytoplasmic chaperone SecB (5, 19, 53). Inner membrane proteins are targeted to the Sec translocon via the signal recognition particle pathway in a cotranslational fashion (19, 37). In E. coli, a small number of proteins are translocated across or integrated into the inner membrane via the twin-arginine protein transport (TAT) pathway (28, 36, 61).

The core of the Sec translocon consists of the integral membrane proteins SecY, SecE, and SecG (38). SecY and SecE, but not SecG, are essential for viability (38). The crystal structure of the SecYEβ complex from the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii suggests that the 10 transmembrane segments of E. coli SecY can be divided into two halves (transmembrane segments 1 to 5 and 6 to 10) that are clamped together by the third and essential transmembrane segment of SecE (65). Recent evidence suggests that although a SecYEG heterotrimer serves as the protein translocation channel, multiple SecYEG heterotrimers may cooperate in protein translocation/insertion (40, 41, 48). SecA, an ATPase that is associated with the Sec translocon, drives the stepwise translocation of secretory proteins and large periplasmic loops of inner membrane proteins across the inner membrane (38). The Sec translocon-associated proteins SecD, SecF, and YajC form a complex that facilitates protein translocation, but they are not required for viability (38). The SecDF-YajC complex is thought to mediate the interplay between the SecYEG protein-conducting channel and YidC, an essential inner membrane protein which appears to be involved in the transfer of transmembrane segments from the Sec translocon into the lipid bilayer (34, 37, 46, 71). Evidence is accumulating that YidC by itself can also mediate the insertion of a subset of membrane proteins (34, 37).

The notion that most secretory and inner membrane proteins require the Sec translocon for translocation and/or insertion is based on studies using focused approaches and a limited number of model proteins, such as the outer membrane protein OmpA and the inner membrane protein FtsQ (21, 48). To study Sec translocon-mediated protein translocation and insertion in a more global way, we performed a comparative subproteome analysis of cells depleted of SecE and cells expressing normal levels of SecE. This approach allowed us to investigate protein mislocalization, aggregation, and changes in the composition of the outer and inner membrane proteomes of cells with strongly reduced Sec translocon levels (1). Our analysis showed that upon SecE depletion, secretory proteins aggregate in the cytoplasm and the cytoplasmic σ32 stress response is induced. This response is activated upon protein misfolding/aggregation in the cytoplasm (4). Interestingly, the effects of reduced Sec translocon levels on the proteomes of the outer and inner membranes were different. Both the steady-state levels and the translocation efficiencies of most outer membrane proteins were reduced. The inner membrane proteome appeared to be differentially affected by the depletion of SecE. The levels of some proteins were reduced in the inner membrane, while the levels of other proteins were unaffected or increased. Notably, our analysis indicated that all integral inner membrane proteins whose levels were unaffected or increased upon SecE depletion lack large periplasmic domains and/or contain only one or two transmembrane segments. This study provides several testable hypotheses and new substrates that can be used to further discover guiding principles for protein translocation and insertion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

In E. coli strain CM124, the chromosomal copy of the gene encoding SecE is inactivated and placed on a plasmid under control of the promoter of the araBAD operon (60). CM124 was cultured in standard M9 minimal medium supplemented with thiamine (10 mM), all amino acids (0.7 mg/ml) except methionine and cysteine, glucose (0.2%, wt/vol), arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol), and ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in an Innova 4330 (New Brunswick Scientific) shaker at 180 rpm. Overnight cultures were washed in fresh medium without arabinose and then diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.035 in fresh medium without arabinose to deplete the SecE in the cells (“SecE-depleted cells”) or in medium containing 0.2% arabinose to induce expression of SecE (“control cells”). Cells were cultured for 6 h. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 with a Shimadzu UV-1601 spectrophotometer.

SDS-PAGE, 1D BN-PAGE, and immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis was used to monitor the levels of the SecE, SecY, SecG, SecA, SecD, SecF, YidC, FtsQ, Lep, Fob, Foc, DegP, Skp, OmpA, OmpF, PhoE, IbpA/B, SecB, Ffh, and PspA proteins in whole-cell lysates and/or inner membranes. Whole cells (0.1 OD600 unit) and purified inner membranes (5 μg of protein) were solubilized in Laemmli solubilization buffer and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Proteins were transferred from the polyacrylamide gels to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blocked and decorated with antisera to the components listed above essentially as described previously (26). Proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) using the ECL system according to the instructions of the manufacturer (GE Healthcare) and a Fuji LAS 1000-Plus charge-coupled device camera. Blots were quantified using the Image Gauge 3.4 software (Fuji). Experiments were repeated with three independent samples. Changes were calculated as follows. The average band intensity for samples of SecE-depleted cells was divided by the average band intensity for samples of control cells. For secretory proteins (DegP, PhoE, Skp, OmpA, and OmpF), the percentage of the precursor and mature forms detected in samples of SecE-depleted cells relative to the mature form detected in samples of control cells was determined. It should be noted that for secretory proteins only the mature form was detected in control cells.

To monitor the abundance of the SecYEG protein-conducting channel, inner membrane vesicles were subjected to one-dimensional (1D) blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) (58), followed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies to SecY, SecE, and SecG. Inner membrane pellets (20 μg of protein) were solubilized in buffer containing 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM bis-Tris-HCl (pH 7.0 at 4°C), and freshly prepared 0.5% (wt/vol) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM). After removal of unsolubilized material by centrifugation (100,000 × g, 30 min), Serva Blue G was added to a final concentration of 0.5% (wt/vol), and the samples were loaded onto the first-dimension gel. The 0.02% Serva Blue G cathode buffer used for BN-PAGE was changed to 0.002% Serva Blue G cathode buffer after one-third of the run in order to prevent excessive binding of Coomassie brilliant blue dye to the PVDF membrane in the subsequent transfer step. Ferritin (440 and 880 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and albumin (66 kDa) (GE Healthcare) were used as molecular mass markers. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane, detected by antisera to SecY, SecE, and SecG, and quantified as described above.

Protein translocation assay.

Translocation of OmpA was monitored essentially as described previously (25). Cultures corresponding to 0.4 OD600 unit were labeled with [35S]methionine (60 μCi/ml [1 Ci = 37 GBq]) for 30 s, and this was followed by precipitation in 10% trichloroacetic acid either immediately or after a chase with cold methionine (final concentration, 0.5 mg/ml) for 3 and 10 min. Trichloroacetic acid-precipitated samples were washed with acetone, resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2% SDS, and immunoprecipitated with antiserum to OmpA. The OmpA precipitate was subjected to standard SDS-PAGE analysis. Gels were scanned with a Fuji FLA-3000 phosphorimager and quantified as described above. The percentage of the precursor and the mature form of OmpA detected in the SecE-depleted cells relative to the mature OmpA detected in the control cells was determined.

Flow cytometry and microscopy.

Analysis of SecE-depleted and control cells using flow cytometry was carried out using a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences). To assess viability, cells were incubated in the dark at room temperature with 30 μM propidium iodide for 15 min (31). For staining of the inner membrane, cells were cultured at 37°C for 30 min with the membrane-specific fluorophore FM4-64 (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 2 μM (24). Cultures were diluted in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline to a final concentration of approximately 106 cells per ml. A low flow rate was used throughout data collection with an average of 250 events per s. Forward and side scatter acquisition was used for comparison of cell morphology (5). Data acquisition was performed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed with FloJo software (Tree Star).

For microscopy, cells were mounted on a slide and immobilized in 1% low-melting-temperature agarose. Microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axioplan2 fluorescence microscope equipped with an Orca-ER camera (Hamamatsu). Images were processed with the AxioVision 4.5 software from Zeiss.

Isolation and analysis of protein aggregates.

Protein aggregates were extracted from whole cells essentially as described previously (59). Cells corresponding to 75 OD600 units were used for each aggregate extraction. The protein contents of cell lysates and aggregate extracts were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Pierce). Aggregates isolated from 0.75 OD600 unit were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 24-cm-long 8 to 16% acrylamide gradient gels. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250, and proteins were identified by mass spectrometry (MS) as described below. The aggregate fraction was also subjected to in-solution digestion, followed by nano-liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem MS (nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS) as described below.

Isolation of inner and outer membranes.

Inner and outer membranes were isolated essentially as described previously (67). Membrane fractions used for immunoblot analysis were prepared from nonradiolabeled cultures. Membrane fractions used for analysis by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DE) (outer membranes) or two-dimensional (2D) BN/SDS-PAGE (inner membranes) were prepared from a mixture of labeled and unlabeled cells as outlined in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Cells corresponding to 1,000 OD600 units were cultured as described above. An aliquot (10 OD600 units) of cells was labeled with [35S]methionine (60 μCi/ml [1 Ci = 37 GBq]) for 1 min, and this was followed by a chase for 10 min with cold methionine (final concentration, 5 mg/ml). Labeled cells were subsequently collected by centrifugation, and cell pellets were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The remainder of the cells (990 OD600 units) was harvested by centrifugation and washed once with buffer K (50 mM triethanolamine [TEA], 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]; pH 7.5). The cell pellets were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Before the cells were broken, labeled and unlabeled cells from the same culture were pooled in a 1:100 ratio. The resulting mixture was resuspended in 8 ml buffer K supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml Pefabloc and 5 μg/ml DNase and lysed by using a French press (two cycles; 18,000 lb/in2). The unbroken cells were removed from the lysate by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min, and the total membrane fraction was collected by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The membrane pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of buffer M (50 mM TEA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT; pH 7.5) and loaded on top of a six-step sucrose gradient consisting of (from bottom to top, in buffer M) 0.5 ml of 55% (wt/wt) sucrose, 1.5 ml of 50% (wt/wt) sucrose, 1.5 ml of 45% (wt/wt) sucrose, 2.5 ml of 40% (wt/wt) sucrose, 2.5 ml of 35% (wt/wt) sucrose, and 2.5 ml of 30% (wt/wt) sucrose. After centrifugation at 210,000 × g for 15 h, the inner membrane and outer membrane fractions were collected from the 35 and 45% sucrose layers, respectively. The collected fractions were diluted in TEA buffer (50 mM TEA, 1 mM DTT; pH 7.5) to obtain a sucrose concentration less than 10%. Membranes were collected by centrifugation at 170,000 × g for 1 h and subsequently resuspended in buffer L (50 mM TEA, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM DTT; pH 7.5). The inner membrane fraction was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the outer membrane fraction was washed in 0.1 M sodium carbonate as described previously (5). Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay. Samples were stored at −80°C.

2DE.

Whole-cell lysates (1 OD600 unit) and [35S]methionine-labeled outer membranes (185 μg of protein) isolated by density centrifugation were analyzed by 2DE using isoelectric focusing in the first dimension and SDS-PAGE in the second dimension (5). Gels used for comparative analysis of whole-cell lysates were stained with high-sensitivity silver stain (47). Gels used for comparative analysis of the outer membrane proteome and all gels used for MS-based identification of proteins were stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue (45). Most proteins in the outer membrane gels gave rise to multiple spots with the same molecular mass but different pIs. This phenomenon was also observed in the outer membrane map of E. coli constructed by Molloy et al. (43). Most “trains of spots” are caused by modifications induced during sample preparation (7), likely due to stepwise deamidation of the asparagine and glutamine residues, resulting in loss of 1 Da and a net loss of one positive charge (73).

Analysis of cytoplasmic membrane fractions by 2D BN/SDS-PAGE.

Comparative 2D BN/SDS-PAGE was performed as described previously (67). In short, [35S]methionine-labeled inner membranes (100 μg of protein) were solubilized in 0.5% (wt/vol) DDM and subjected to BN electrophoresis in the first dimension and denaturing SDS-PAGE in the second dimension. For calibration, ferritin (440 and 880 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and albumin (66 kDa) (GE Healthcare) were used as molecular mass markers. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (5).

Image analysis and statistics.

Stained gels were scanned using a GS-800 densitometer from Bio-Rad. Radiolabeled gels were scanned with a Fuji FLA-3000 phosphorimager. Spots were detected, matched, and quantified using PDQuest software, version 8.0 (Bio-Rad). The analysis of Coomassie brilliant blue-stained and [35S]methionine-labeled outer and inner membrane proteins was done using the same set of gels. In all cases, each analysis set consisted of at least three gels for each replicate group (i.e., SecE-depleted cells and the control). Each gel in a set represented an independent sample (i.e., a sample from a different bacterial colony, culture, and membrane preparation). Independent samples were subjected to 2DE or 2D BN/SDS-PAGE and image analysis in parallel (i.e., en groupe). Spot quantities were normalized using the “total intensity of valid spots” method to compensate for non-expression-related variations in spot quantities between gels (there were no significant variations in the total spot quantity between the two groups [SecE depletion and control]). Since protein aggregates can cosediment with outer membranes during density gradient centrifugation, an additional normalization step was required for analysis of the outer membrane gels (35, 39). First, to distinguish between outer membrane spots and contaminating aggregate spots, the outer membrane fractions from SecE-depleted and control cells were subjected to aggregate extraction as described above. The resulting extracts were analyzed by 2DE, and proteins in the aggregates were visualized by staining with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue. Spots detected in the gels of the aggregate extract were removed from the outer membrane analysis set if the intensity of a spot in the aggregate gel was more than 5% of the intensity of the spot detected in the outer membrane gels. The quantities of the remaining spots were normalized using the “total quantity of valid spots” method to correct for the contribution of protein aggregates on protein loading. Spots detected by means of phosphorimaging were normalized using the correction value calculated for the corresponding Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel to allow correction for errors in protein loading while differences in labeling efficiency between the control and SecE-depleted cells were retained. The changes for spots matched in different gels were calculated by dividing the average spot intensity for gels with SecE-depleted samples by the corresponding value for gels with control samples. PDQuest was set to detect differences that were found to be statistically significant using the Student t test and a 95% level of confidence, including qualitative differences “on-off responses”) present in all gels in a group. Saturated spots were excluded from the analysis. In order to present qualitative responses in bar diagrams with a logarithmic scale, on and off responses were given values of 100- and 0.01-fold, respectively (67).

MS-based identification of proteins.

Coomassie brilliant blue-stained protein spots or bands were excised, washed, and digested with modified trypsin, and peptides were extracted manually or automatically (ProPic and Progest; Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, MI). Peptides were applied to a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) target plate as described previously (50). Mass spectra were obtained automatically by MALDI-time of flight (TOF) MS in reflectron mode (Voyager-DE-STR; PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA), followed by automatic internal calibration using tryptic peptides from autodigestion. The spectra were analyzed for monoisotopic peptide peaks (m/z range, 850 to 5,000) using the software MoverZ from Genomic Solutions (http://65.219.84.5/moverz.html) with a signal-to-noise ratio threshold of 3.0. Matrix and/or autoproteolytic trypsin fragments were not removed. Spectral annotations (in particular, assignments of monoisotopic masses) were verified by manual inspection for a large number of measurements. The resulting peptide mass lists were used to search the Swiss-Prot 45.0 database (release 10/04) for E. coli with Mascot (v2.0) in automated mode (www.matrixscience.com), using the following search parameters or criteria: significant protein MOWSE score at P < 0.05; no missed cleavages allowed; variable methionine oxidation; fixed carbamidomethylation of cysteines; and a minimum mass accuracy of 50 ppm. The search result pages were extracted and analyzed by using an additional in-house filter (Q. Sun and K. J. van Wijk, unpublished) by applying the following three criteria for positive identification: (i) minimum MOWSE score of ≥50; (ii) ≥4 matching peptides with an error distribution within ±25 ppm; and (iii) ≥15% sequence coverage. The false-positive rates were less than 1%, as determined by searching with the .pkl list against the E. coli database (Swiss-Prot) mixed with a randomized version of the E. coli database, generated using a Perl script from Matrix Science.

Aggregate fractions isolated from whole cells were subjected to in-solution digestion with modified trypsin (51). The resulting peptide mixtures were analyzed by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS in automated mode using a quadruple/orthogonal-acceleration TOF tandem mass spectrometer (Q-TOF; Micromass). The spectra were used to search the Swiss-Prot database (downloaded locally) automated using Mascot (v2.0) (www.matrixscience.com). When Mascot was searched, the maximum precursor and fragment errors were 1.2 and 0.6 Da, respectively. For all significant MS/MS identifications based on a single peptide, spectral quality and matching y and b ion series were manually verified (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

RESULTS

Characterization of the SecE depletion strain CM124.

E. coli strain CM124 was used to study the consequences of depletion of SecE for protein insertion and translocation. In CM124, the chromosomal copy of secE is inactivated, and a copy of secE is placed on a plasmid under control of the promoter of the araBAD operon (60). Cells were cultured aerobically in M9 minimal medium in the presence of arabinose to induce expression of SecE (these cells are referred to in this paper as “control cells”) and in the absence of arabinose to deplete cells of SecE. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 (Fig. 1A). As expected, the growth of CM124 cells cultured in the absence of arabinose was much slower than the growth in control cultures.

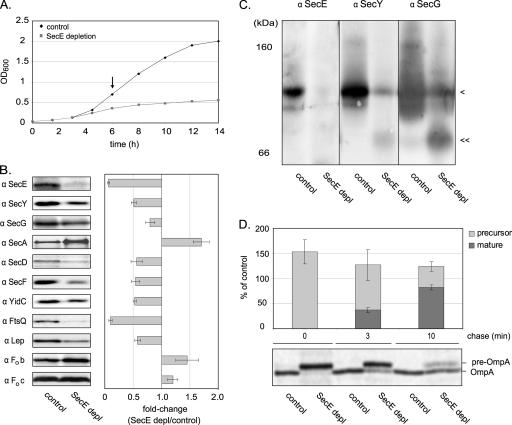

FIG. 1.

Effect of SecE depletion on growth, steady-state levels of Sec components, model inner membrane proteins, and OmpA translocation. (A) Effect of SecE depletion on cell growth. Growth of CM124 cultured in the presence (control) and absence (SecE depletion) of 0.2% arabinose was monitored by measuring the OD600. (B) Quantification of the steady-state levels of SecE, SecY, SecG, SecA, SecD, SecF, and YidC, as well as the model substrates FtsQ, Lep, Fob, and Foc, in the inner membrane of SecE-depleted (SecE depl) and control cells. Inner membranes from SecE-depleted and control cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with antibodies to the components listed above. The graph indicates the average changes in the intensities of the bands upon SecE depletion compared to the control. The quantification was based on three independent samples. α, antibody. (C) Analysis of the integrity and abundance of the SecYEG complex. Inner membranes from SecE-depleted and control cells were subjected to BN-PAGE analysis followed by detection of SecE, SecY, and SecG by immunoblotting. The position of the SecYEG trimer is indicated by one arrowhead, and the position of the putative SecYG complex is indicated by two arrowheads. (D) Effect of depletion of SecE on the translocation of the major outer membrane protein OmpA. SecE-depleted and control cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 s and, after cold methionine was added, chased for 3 and 10 min. OmpA was immunoprecipitated and subjected to standard SDS-PAGE analysis, and labeled material was detected by phosphorimaging. The bars in the graph indicate the percentages of the precursor and mature forms of OmpA detected in the SecE-depleted cells compared to the amounts of mature OmpA detected in the control cells. The experiment was repeated three times.

For all experiments, cells were harvested 6 h after inoculation. At this time point, control cells were in the mid-log phase with an OD600 of 0.8, and SecE-depleted cells reached an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4. Inner membranes were isolated from control cells and SecE-depleted cells, and the levels of SecE, SecY, SecG, SecA, SecD, SecF, and YidC were analyzed by immunoblotting. The level of SecE in the membrane of depleted cells was less than 10% of the level of the SecE detected in membranes prepared from control cells. The levels of SecY and SecG in SecE-depleted membranes were reduced to 50 and 20%, respectively (Fig. 1B). SecY is degraded by the FtsH protease in the absence of SecE (1). Since the Sec translocon is composed of SecY, SecE, and SecG in a 1:1:1 ratio (65), this indicates that the SecE-depleted membrane contains pools of SecY and SecG, which are not in a SecYEG complex. The abundance of SecYEG heterotrimers in SecE-depleted membranes was monitored by BN-PAGE combined with immunoblotting (Fig. 1C). For this purpose, inner membranes prepared from SecE-depleted and control cells were solubilized in 0.5% DDM (8). Upon depletion of SecE, only a minute amount of the SecYEG heterotrimer could be detected. Interestingly, a complex that most likely represented a SecYG heterodimer could be detected in membranes of SecE-depleted cells but not in control membranes.

The amount of SecA was almost doubled in SecE-depleted membranes (Fig. 1B) (44), whereas the levels of SecD, SecF, and YidC were reduced by approximately 50%. In addition, the steady-state levels of the well-studied model proteins FtsQ, Lep, Fob, and Foc were monitored by immunoblotting (Fig. 1B) (16, 21, 63, 66, 72). As expected, the accumulation levels of the Sec translocon-dependent inner membrane proteins FtsQ and Lep were strongly reduced upon SecE depletion, whereas the level of the Sec translocon-independent protein Foc was slightly increased. To our surprise, the level of Fob was somewhat increased, contradicting a previous proposition that translocation of Fob is dependent on the Sec translocon (72).

Pulse-chase experiments showed that translocation of OmpA was delayed but not abolished upon SecE depletion (Fig. 1D). Possibly as a response to compensate for the delayed translocation, the total (pre-)OmpA accumulation was initially higher in the SecE-depleted cells than in the control cells.

Flow cytometry and microscopy.

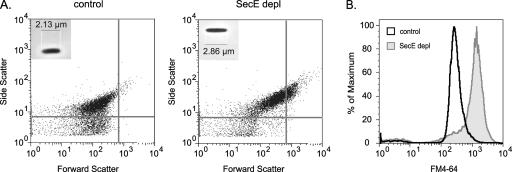

The integrity of the inner membrane of SecE-depleted and control cells was monitored using propidium iodide staining combined with flow cytometry (31). This analysis showed that 9.0% ± 2.0% of SecE-depleted cells stained fluorescently red with propidium iodide, compared to 1.0% ± 0.3% of the control cells, indicating that SecE depletion had only a minor impact on the integrity of the inner membrane. Furthermore, we detected small increases in both the forward scatter and side scatter of cells depleted of SecE (Fig. 2A). This indicates that SecE-depleted cells are slightly bigger than control cells and most likely contain extra internal structures (i.e., extra membranes and/or protein aggregates). Light microscopy showed that SecE-depleted cells were slightly elongated compared to the control cells (Fig. 2A). Cellular membranes in SecE-depleted cells and control cells were stained with the fluorescent dye FM4-64 and analyzed by flow cytometry (24). SecE-depleted cells showed fourfold-greater fluorescence than control cells, indicating that there were increased amounts of membranes upon SecE depletion (Fig. 2B). This is in keeping with the observation that SecE depletion induces the formation of endoplasmic membranes (29).

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric properties of control and SecE-depleted (SecE depl) cells. SecE-depleted and control cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Size of the population (forward scatter) plotted versus granularity (side scatter) for SecE-depleted and control cells. The insets show microscope images of representative cells from the SecE-depleted and control cultures. Cell length is indicated by scale bars. (B) Histograms representing the fluorescence of cultures stained with the membrane-specific fluorophore FM4-64.

SecE depletion leads to accumulation of secretory proteins in the cytoplasm and induction of the σ32 stress response.

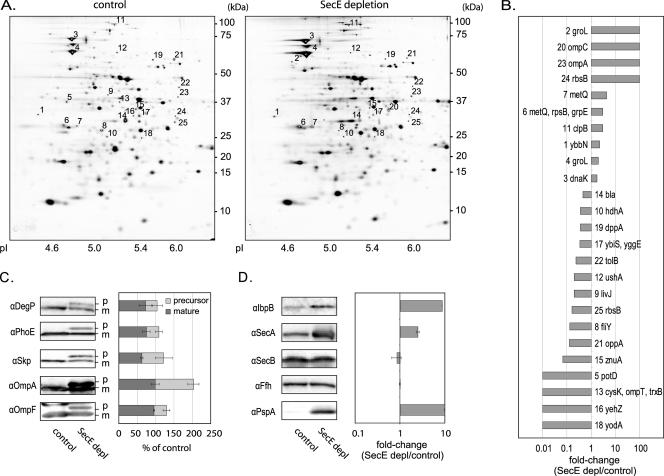

Whole-cell lysates of SecE-depleted and control cells were compared by using 2DE and immunoblot analysis. The comparative 2DE analysis was based on four biological replicates. Proteins were separated by using denaturing immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (pH 4 to 7) in the first dimension and by Tricine-SDS-PAGE in the second dimension. Gels were stained with silver or colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue, and spot volumes were compared using PDQuest. This analysis demonstrated that the volumes of 25 spots were significantly (P < 0.05) changed in the lysates of SecE-depleted cells compared to the control; the intensity increased for 10 spots and decreased for 15 spots. The affected spots were excised and used for protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS and peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) (Fig. 3A and Table 1). Spot statistics and MS data are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The effects of SecE depletion on protein accumulation levels are expressed as changes (SecE depletion/control) in Fig. 3B.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of whole-cell lysates of SecE-depleted and control cells by 2DE and immunoblotting. (A) Comparative 2DE analysis of total lysates from SecE-depleted and control cells. Proteins from 1 OD600 unit of solubilized cells were separated by 2DE. Proteins were visualized by silver staining, and differences between SecE-depleted and control cells were analyzed using PDQuest. Twenty-five spots were significantly (P < 0.05) affected by SecE depletion. Proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF using spots excised from gels stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (Table 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). If several proteins were identified in the same spot, the first gene listed corresponds to the gene with the highest Mascot MOWSE score. Primary gene designations were obtained from Swiss-Prot (www.expasy.org). Annotated spots were matched on the silver-stained gels shown using PDQuest. (B) Graph showing the changes in spots that are significantly (P < 0.05) affected by SecE depletion. Changes were calculated by determining the average spot intensities in SecE-depleted samples (SecE depl)/average spot intensities in control samples. A change of 100-fold indicates that a spot was detected only in SecE-depleted samples (“on response”), and a change of 0.01-fold indicates that a spot was detected only in the control samples (“off response”). (C) Quantification of the precursor (p) and mature (m) forms of secretory proteins in SecE-depleted and control cells by immunoblotting. Whole cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with antibodies to two periplasmic proteins (DegP and Skp) and three outer membrane proteins (OmpA, OmpF, and PhoE). The bars in the graph indicate the percentages of the precursor and mature forms of the proteins detected in the SecE-depleted cells compared to the mature form detected in the control cells. The quantification was based on three independent samples. α, antibody. (D) Quantification of the levels of IbpA/B, SecA, Ffh, SecB, and PspA in whole cells. SecE-depleted and control cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with antibodies to the components listed above. The graph shows the changes calculated by determining the average band intensities detected in SecE-depleted cells/average band intensities detected in control cells. The quantification was based on three independent samples.

TABLE 1.

Comparative 2D gel analysis and MS identification of proteins from total lysates of SecE-depleted and control cellsa

| Spotb | Genec | Protein

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation or functiond | Localizatione | Predicted mol wt (103) (precursor/mature)f | Predicted pI (precursor/mature)g | Observed mol wt (103)h | Observed pIi | Change (fold) (SecE depleted/control)j | ||

| 1 | ybbN | YbbN | c | 31.8 | 4.5 | 31.8 | 4.5 | 2.23 |

| 2 | groL | 60-kDa chaperonin GroELk | c | 57.3 | 4.85 | 55.3 | 4.68 | 100 |

| 3 | dnaK | Chaperone protein DnaK | c | 69.1 | 4.83 | 68.9 | 4.83 | 1.74 |

| 4 | groL | 60-kDa chaperonin GroELk | c | 57.3 | 4.85 | 60.2 | 4.83 | 1.96 |

| 5 | potD | Spermidine/putrescine-binding periplasmic protein | p | 38.9/36.5 | 5.24/4.86 | 35.87 | 4.76 | 0.01 |

| 6 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im lp/om lp | 38.9/36.5 | 5.24/4.86 | 27.25 | 4.73 | 2.96 |

| 6 | rpsB | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | c | 26.7 | 6.61 | 27.25 | 4.73 | 2.96 |

| 6 | grpE | Protein GrpE | c | 21.8 | 4.68 | 27.25 | 4.73 | 2.96 |

| 7 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im lp/om lp | 38.9/36.5 | 5.24/4.86 | 27.4 | 4.88 | 4.32 |

| 8 | fliY | Cystine-binding periplasmic protein | p | 29.3/26.1 | 6.22/5.29 | 25.58 | 5.18 | 0.13 |

| 9 | livJ | Leu/Ile/Val-binding protein | p | 39.1/36.8 | 5.54/5.28 | 38.7 | 5.22 | 0.20 |

| 10 | hdhA | 7-Alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | c | 26.8 | 5.22 | 23.39 | 5.21 | 0.37 |

| 11 | clpB | Chaperone ClpB | c | 95.6 | 5.37 | 79.12 | 5.29 | 2.96 |

| 12 | ushA | Protein UshA | p | 60.8/58.2 | 5.47/5.4 | 59.65 | 5.31 | 0.20 |

| 13 | cysK | Cysteine synthase A | amb | 34.5 | 5.83 | 35.47 | 5.34 | 0.01 |

| 13 | ompT | Protease 7 | om | 35.6/33.5 | 5.76/5.38 | 35.47 | 5.34 | 0.01 |

| 13 | trxB | Thioredoxin reductase | c | 34.6 | 5.3 | 35.47 | 5.34 | 0.01 |

| 14 | bla | Beta-lactamase TEM | p | 31.5/28.9 | 5.69/5.46 | 29.8 | 5.39 | 0.46 |

| 15 | znuA | High-affinity zinc uptake system protein ZnuA | p | 33.8/31.1 | 5.61/5.44 | 33.29 | 5.52 | 0.07 |

| 16 | yehZ | Hypothetical protein YehZ | p | 32.6/30.2 | 5.82/5.56 | 31.19 | 5.48 | 0.01 |

| 17 | ybiS | YbiS | p | 33.42/30.86 | 5.99/5.6 | 31.19 | 5.57 | 0.34 |

| 17 | yggE | Hypothetical protein YggE | p | 26.6/24.5 | 6.1/5.60 | 31.19 | 5.57 | 0.34 |

| 18 | yodA | Metal-binding protein YodA | p | 24.8/22.3 | 5.91/5.66 | 23.15 | 5.6 | 0.01 |

| 19 | dppA | Periplasmic dipeptide transport protein | p | 60.3/57.4 | 6.21/5.75 | 55.21 | 5.74 | 0.36 |

| 20 | ompC | Outer membrane protein C | om | 40.4/38.3 | 4.58/4.48 | 32.71 | 5.76 | 100 |

| 21 | oppA | Periplasmic oligopeptide-binding protein | p | 60.97/58.5 | 6.05/5.85 | 54.94 | 6.02 | 0.13 |

| 22 | tolB | TolB | p | 46.0/43.6 | 6.98/6.14 | 41.31 | 6.09 | 0.23 |

| 23 | ompA | Outer membrane protein A | om | 37.2/35.2 | 5.99/5.60 | 37.3 | 6.07 | 100 |

| 24 | rbsB | d-Ribose-binding periplasmic protein | p | 31.0/28.5 | 6.85/5.99 | 30.67 | 6.03 | 100 |

| 25 | rbsB | d-Ribose-binding periplasmic protein | p | 31.0/28.5 | 6.85/5.99 | 28.46 | 6.02 | 0.17 |

Spots visualized by silver staining (Fig. 3A) were quantified and compared using PDQuest. Spot quantities were normalized using the “total quantity of valid spot” method. Changes of 0.01- and 100-fold correspond to spots that are missing (“off response”) or turned on (“on response”) in the SecE-depleted cells, respectively. All spots that were significantly (P < 0.05) changed upon SecE depletion were excised from gels stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue, and proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF.

The numbers correspond to the spots in the 2D gel images in Fig. 3A.

Gene designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Protein designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Localization based on the information given in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli. Unknown localizations were predicted by PSORT. Abbreviations: amb, ambiguous; c, cytoplasmic; im lp, inner membrane lipoprotein; om, outer membrane; om lp, outer membrane lipoprotein; p, periplasmic.

Protein sizes predicted from amino acid sequences. Two sizes are given for secretory proteins; the first size is the size of the precursor form, and the second size is the size of the mature form of the protein.

pIs predicted from the amino acid sequence. Two values are given for secretory proteins; the first value is the pI for the precursor form, and the second value is the pI for the mature form of the protein.

Sizes of proteins calculated from the spot positions on the 2D gels used for the analysis.

pIs of proteins calculated from the spot positions on the 2D gels used for the analysis.

Changes expressed as the ratio of the average intensity of significantly (P < 0.05) affected spots in the SecE depletion gels to the average intensity of matched spots in the control gels.

The occurrence of different forms of GroEL is explained in reference 55.

The accumulation levels of a number of secretory proteins (β-lactamase, DppA, FliY, LivJ, PotD, OmpT, OppA, TolB, UshA, YbiS, YehZ, YggE, YodA, and ZnuA) were reduced in SecE-depleted cells. Based on the pI and molecular weight, the spots corresponded to the processed forms of these proteins (Table 1). OmpC, MetQ, and OmpA were identified in spots that were stronger in lysates of SecE-depleted cells. The positions of the spots in which OmpC and MetQ were identified suggested that these spots contained degraded forms of these proteins. Based on pI and molecular weight, the OmpA spot likely contained pre-OmA. This conclusion was supported by an MS analysis (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). RbsB was identified in two spots, one high-intensity spot that was reduced upon SecE depletion and a faint spot that appeared only with SecE-depleted cells. It is likely that the high-intensity spot corresponded to the mature form of the protein and the faint spot corresponded to the precursor form. However, based on pI and molecular weight it was not possible to unambiguously determine this.

To study the effect of SecE depletion in more detail, the accumulation levels of the periplasmic proteins DegP and Skp and the outer membrane proteins OmpA, OmpF, and PhoE were monitored by immunoblotting (Fig. 3C). Upon SecE depletion, the precursor forms of all these proteins were detected, indicating that there was accumulation in the cytoplasm due to hampered translocation. In the case of Skp, DegP, and PhoE, this was accompanied by significant decreases in the levels of the mature forms of the proteins. Interestingly, the total levels of DegP and Skp were not affected upon SecE depletion. This suggests that no extracytoplasmic stress responses are activated upon SecE depletion (57). The accumulation level of the mature form of OmpA was unaffected by the SecE depletion, while the accumulation level of OmpF was slightly reduced.

Upon SecE depletion, the accumulation levels of the σ32-inducible, cytoplasmic chaperones DnaK, GroEL, and ClpB were increased (Fig. 3B). The up-regulation of DnaK and GroEL was confirmed by Western blotting (results not shown). Since the inclusion body proteins IbpA/B, SecA, SecB, and Ffh and phage shock protein A (PspA) were not identified in the 2D gels, we monitored their accumulation levels by immunoblotting (Fig. 3D). The level of the heat shock chaperones IbpA/B, also part of the σ32 regulon, was increased. Inclusion body proteins associate with protein aggregates and facilitate the extraction of proteins from aggregates by ClpB and DnaK (42). In agreement with the membrane blotting experiments (see above), the total level of SecA was increased in SecE-depleted cells, consistent with insufficient Sec translocon capacity (44). The accumulation levels of SecB and Ffh, two components involved in the targeting of secretory and inner membrane proteins, respectively, to the Sec translocon were both unaffected upon SecE depletion. This indicates that the protein targeting capacity is not affected upon SecE depletion. The level of PspA was monitored since the electrochemical potential plays an important role in protein translocation and the expression of PspA is up-regulated when it is affected. Similar to several other translocation and insertion mutant strains, a considerable PspA response was detected in SecE-depleted cells (18).

Taken together, the up-regulation of SecA and the accumulation of the unprocessed forms of secretory proteins indicate that protein translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane is strongly hampered. Furthermore, the accumulation levels of the σ32-regulated chaperones DnaK, GroEL, ClpB, and IbpA/B are all increased upon SecE depletion, suggesting that reduced Sec translocon levels lead to protein misfolding/aggregation in the cytoplasm.

Accumulation of cytoplasmic protein aggregates in SecE-depleted cells.

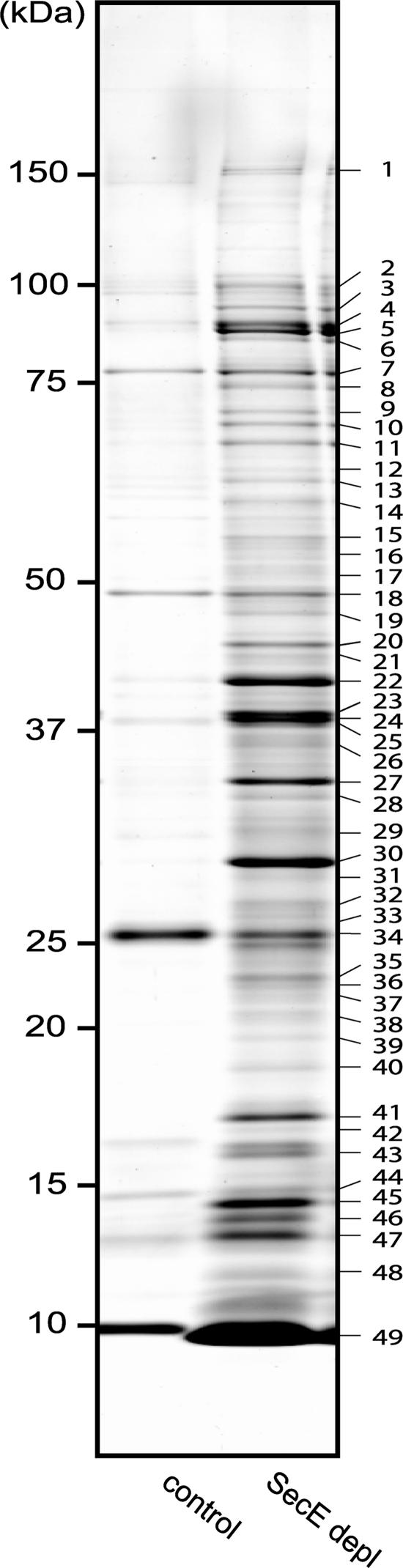

Protein aggregates were extracted from whole cells depleted of SecE. The aggregates from SecE-depleted cells contained 2.6% of the total cellular protein, compared to 0.3% in the control. The protein composition of the aggregates was analyzed by 1D gel electrophoresis followed by in-gel digestion and analysis by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF (Fig. 4; see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS of solubilized aggregates digested with trypsin (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In total, 61 proteins were identified in aggregates isolated from cells depleted of SecE; these proteins included 19 secretory proteins, 5 inner membrane proteins, 36 cytoplasmic proteins, and 1 protein with a localization that could not be unambiguously predicted (Table 2). Among the identified cytoplasmic proteins were the chaperones IbpA, DnaK, and DnaJ. The MS/MS analysis revealed that at least four of the secretory proteins, OmpA, Lpp, β-lactamase, and SlyB, contained an uncleaved signal sequence (results not shown), indicating that these proteins aggregate in the cytoplasm rather than in the periplasm. The identified inner membrane proteins ElaB and YqjD contain one predicted transmembrane segment, while YhjK contains two such segments. Penicillin-binding protein 5 (DacA) and penicillin-binding protein 6 (DacC) are probably attached to the inner membrane via a C-terminal amphiphilic α-helix (27). It is possible that the number of identified inner membrane proteins is somewhat underrepresented since the typical absence of lysine and arginine in the transmembrane domain regions leads to few peptides and large peptides upon digestion with trypsin (70).

FIG. 4.

Characterization of aggregates isolated from SecE-depleted cells (SecE depl). Aggregates isolated from SecE-depleted and control cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue and subsequently identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF (Table 2; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). If several proteins were identified in the same band, the first gene listed corresponds to the protein with the highest Mascot MOWSE score.

TABLE 2.

MS identification of proteins in aggregates isolated from lysates of SecE-depleted and control cellsa

| Band(s)b | Hit rankc | Gened | Protein

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation or functione | Localization or no. of transmembrane segmentsf | Predicted mol wt (103) (precursor/mature)g | |||

| 2 | adhE | Aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase | c | 96.1 | |

| 17 | atpA | ATP synthase subunit alpha | c, im ass | 55.4 | |

| 22, 30, 33 | 1 | bla | Beta-lactamase TEM | p | 31.6/28.9 |

| 6 | clpB | Chaperone ClpB | c | 95.7 | |

| 38 | 25 | crp | Catabolite gene activator | c | 23.6 |

| 28 | cysK | Cysteine synthase A | amb | 34.4 | |

| 14 | cysN | Sulfate adenylyltransferase subunit 1 | c | 52.6 | |

| 25 | dacA | Penicillin-binding protein 5 | 1* | 40.3/38.3 | |

| 23 | dacC | Penicillin-binding protein 6 | 1* | 43.6/40.8 | |

| 19 | degP | Protease do | p | 49.4/46.8 | |

| 23 | dnaJ | Chaperone protein DnaJ | c | 41.1 | |

| 9 | dnaK | Chaperone protein DnaK | c | 69.1 | |

| 42 | 13 | dps | DNA protection during starvation protein | c | 18.6 |

| 14 | elaB | ElaB | 1 | 11.3 | |

| 4, 5 | 6 | fusA | Elongation factor G | c | 77.6 |

| 18 | 12 | glgA | Glycogen synthase | c | 53.0 |

| 7, 36 | 17 | glgB | 1,4-Alpha-glucan branching enzyme | c | 84.3 |

| 11 | glmS | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | c | 66.9 | |

| 16 | guaB | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase | c | 52.0 | |

| 11, 36 | htpG | Chaperone protein HtpG | c | 66.0 | |

| 21 | hupA | DNA-binding protein HU-alpha | c | 9.5 | |

| 46, 47 | 16 | ibpA | Small heat shock protein IbpA | c | 15.8 |

| 23 | iscS | Cysteine desulfurase | c | 45.2 | |

| 49 | 9 | lpp | Major outer membrane lipoprotein | om lp | 8.3/6.4 |

| 12 | lysS | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase | c | 57.6 | |

| 4, 5 | 15 | metE | 5-Methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase | c | 84.7 |

| 26 | mreB | Rod shape-determining protein MreB | c | 37.1 | |

| 29 | nlpD | Lipoprotein NlpD | im lp | 40.2/37.5 | |

| 27, 33, 34 | 3 | ompA | Outer membrane protein A | om | 37.2/35.2 |

| 24, 25 | 5 | ompC | Outer membrane protein C | om | 40.3/38.3 |

| 23, 24 | 18 | ompF | Outer membrane protein F | om | 39.3/37.1 |

| 24 | ompT | Protease 7 | om | 35.5/33.5 | |

| 41 | 8 | ompX | Outer membrane protein X | om | 18.7/16.2 |

| 13 | ptsI | Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase | c | 63.6 | |

| 35 | rplC | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | c | 22.2 | |

| 37 | rplD | 50S ribosomal protein L4 | c | 22.1 | |

| 40 | 24 | rplE | 50S ribosomal protein L5 | c | 20.5 |

| 39 | rplF | 50S ribosomal protein L6 | c | 18.9 | |

| 44 | rplI | 50S ribosomal protein L9 | c | 15.8 | |

| 1 | rpoC | DNA-directed RNA polymerase β′ chain | c | 155.1 | |

| 10, 31 | rpsA | 30S ribosomal protein S1 | c | 61.2 | |

| 32 | rpsB | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | c | 26.7 | |

| 19, 21 | rpsC | 30S ribosomal protein S3 | c | 25.8 | |

| 43 | rpsE | 30S ribosomal protein S5 | c | 17.5 | |

| 40 | rpsG | 30S ribosomal protein S7 | c | 20.0 | |

| 48 | 26 | rpsJ | 30S ribosomal protein S10 | c | 11.7 |

| 3 | secA | Preprotein translocase subunit SecA | c | 102.0 | |

| 43, 44 | 10 | skp | Chaperone protein Skp | p | 17.7/15.7 |

| 45 | 4 | slyB | Outer membrane lipoprotein SlyB | om lp | 15.6/13.8 |

| 25 | spb | Sulfate-binding protein | p | 18.7/16.2 | |

| 20 | 7 | tolB | TolB | p | 36.6/34.7 |

| 15 | tolC | Outer membrane protein TolC | om | 54.0/51.5 | |

| 2 | tufA | Elongation factor Tu | c | 43.3 | |

| 8 | typA | GTP-binding protein TypA/BipA | c | 67.4 | |

| 20 | yajG | Uncharacterized lipoprotein YajG | om lp | 21.0/19.0 | |

| 35 | yfiO | Lipoprotein YfiO | om lp | 23.9/21.7 | |

| 11 | ygiW | YgiW | p | 14.0/12.0 | |

| 27 | yhjK | YhjK | 2 | 73.1 | |

| 25 | 28 | yncE | Hypothetical protein YncE | sec | 38.6/35.3 |

| 22 | yqjD | Hypothetical protein YqjD | 1 | 11.1 | |

| 35 | yrbC | YrbC | sec | 23.9/21.7 | |

Protein aggregates were extracted from lysates of SecE-depleted and control cells. The protein content of the aggregates was analyzed by 1D electrophoresis followed by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF (Fig. 4; see Table S2 in the supplemental material) or nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of solubilized aggregates digested with trypsin (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

The numbers correspond to the bands in the 1D gel shown in Fig. 4.

The ranking is based on the Mascot MOWSE score of proteins identified by in-solution digestion/nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS.

Gene designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Protein designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Localization based on the information given in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli. Unknown localizations were predicted by PSORT. For integral membrane proteins, the numbers of transmembrane segments are indicated. An asterisk indicates that the membrane-inserted segment may act as an anchor rather than as a true transmembrane segment. Abbreviations: amb, ambiguous; c, cytoplasmic; im ass, inner membrane associated; im lp, inner membrane lipoprotein; om, outer membrane; om lp, outer membrane lipoprotein; p, periplasmic; sec, secretory.

Protein sizes were predicted from amino acid sequences. Two sizes are given for secretory proteins; the first size is the size of the precursor form, and the second size is the size of the mature form of the protein.

The intensities of the bands in the gel shown in Fig. 4 were quantified to get an estimate of the relative abundance of different classes of proteins in the aggregates isolated from SecE-depleted cells. About 70% of the total band intensity represented secretory proteins, and about 18% represented cytoplasmic proteins, with the cytoplasmic chaperones DnaK and IbpA together constituting 2%.

Effect of SecE depletion on the outer and inner membrane proteomes.

To study the effect of SecE depletion on the insertion and composition of the inner and outer membrane proteomes, cells were labeled with [35S]methionine. Outer and inner membranes were subsequently isolated using a combination of a French press and sucrose gradient centrifugation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The outer membrane proteome was analyzed by 2DE using isoelectric focusing in the first dimension and SDS-PAGE in the second dimension (5). The inner membrane proteome was analyzed with 2D BN/SDS-PAGE with an immobilized first dimension, which allowed reliable comparative analysis of 2D BN/SDS gels (67). Gels were stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue for detection of the steady-state proteome, while [35S]methionine-labeled proteins (i.e., proteins synthesized and inserted during the 1-min pulse and the 10-min chase) were detected by phosphorimaging. As expected, more spots were detected with Coomassie brilliant blue staining than with phosphorimaging. Spot intensities were quantified and compared using PDQuest. Each analysis set contained at least three biological replicates, and statistically significant changes were identified using the Student t test and a 95% level of confidence. Interestingly, although quantitative differences were observed, SecE depletion led to qualitatively similar effects on spots detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining or phosphorimaging. Spots were excised and used for protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF.

Outer membrane proteome.

MS analysis of the Coomassie brilliant blue-stained spots in the 2D gels of the outer membrane proteome resulted in identification of 39 different proteins from 48 spots (Fig. 5A; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Forty of these spots could be matched with spots detected by phosphorimaging (Fig. 5B). We found that the outer membrane fraction of SecE-depleted cells was contaminated with aggregates that can cosediment with outer membranes during density gradient centrifugation (35, 39). The spots corresponding to aggregated proteins were identified and removed from the analysis set as described in Materials and Methods (see Table S3 and Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

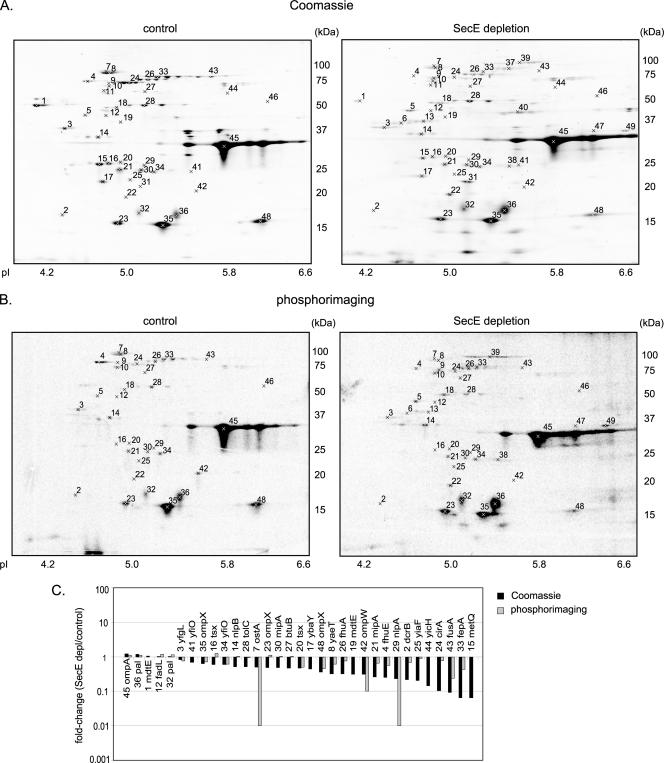

FIG. 5.

2DE analysis of the outer membrane proteome from SecE-depleted (SecE depl) and control cells. Cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 1 min, which was followed by a chase for 10 min with cold methionine. The outer membrane fractions were isolated by density centrifugation from a mixture of labeled and nonlabeled cells as outlined in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material (see Materials and Methods for details). The outer membrane fractions were used for separation by 2DE. Proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF using spots excised from with Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gels (Table 3; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The outer membrane fraction of SecE-depleted cells was contaminated with aggregates that cosedimented with the outer membrane during density centrifugation (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). The spots corresponding to the proteins in these aggregates were identified and removed from the analysis set as described in Materials and Methods. Differences in the outer membrane proteomes of the SecE-depleted and control cells were analyzed using PDQuest. Significantly affected (P < 0.05) proteins are indicated in Table 3 and in Table S3 in the supplemental material. (A) Representative 2D gels showing proteins in the outer membrane fraction stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue (protein steady-state levels). (B) Representative 2D gels showing proteins in the outer membrane fraction detected by phosphorimaging (protein insertion). (C) Graph showing the changes (average spot intensity for SecE-depleted samples/average spot intensity for control sample) for proteins visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (black bars) and phosphorimaging (gray bars). A change of 100-fold indicates that a spot was detected only in SecE-depleted samples (“on response”), and a change of 0.01-fold indicates that a spot was detected only in the control samples (“off response”). The numbers correspond to spots on the gels in panels A and B.

Figure 5C shows the average changes in the spot intensities (SecE depletion/control) for proteins detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining and by phosphorimaging. Statistically significant (P < 0.05) changes are indicated in Table 3 and in Table S3 in the supplemental material. The steady-state levels and insertion efficiencies of most outer membrane proteins were reduced upon SecE depletion. The levels of three outer membrane proteins, OmpA, Pal, and FadL, were unaffected or slightly increased upon SecE depletion. After the 10-min chase, the level of [35S]methionine-labeled OmpA detected in the outer membrane of SecE-depleted cells was not significantly affected, indicating that translocation of OmpA was slowed but not abolished upon SecE depletion. Furthermore, the steady-state level of OmpA was increased by approximately 20% (Fig. 5A and Table 3; see Table S3 in the supplemental material), which is in keeping with the pulse-chase analysis shown in Fig. 1D.

TABLE 3.

Comparative 2D gel analysis and MS identification of proteins in the outer membrane fraction of SecE-depleted and control cellsa

| Spotb | Genec | Swiss-Prot accession no. | Protein

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation or functiond | Localization or no. of transmembrane segmentse | Predicted mol wt (103) (precursor/mature)f | Predicted pI (precursor/mature)g | Observed mol wt (103)h | Observed pIi | Coomassie brilliant blue change (fold) (SecE depleted/control)j | Phosphorimaging change (fold) (SecE depleted/control)j | |||

| 1 | mdtE | P37636 | Multidrug resistance protein MdtE | im lp | 41.3/38.9 | 5.73/5.12 | 53.22 | 4.14 | 1.06 | ND |

| 2 | dcrB | P0AEE1 | DcrB | amb | 19.8/17.8 | 5.09/4.91 | 17.7 | 4.29 | 0.22 | 0.70 |

| 3 | yfgL | P77774 | Lipoprotein YfgL | om lp | 41.9/39.9 | 4.72/4.61 | 37.75 | 4.35 | 0.83 | 0.76 |

| 4 | fhuE | P16869 | FhuE receptor | om | 81.2/77.4 | 4.75/4.72 | 77.17 | 4.65 | 0.25 | 0.56 |

| 5 | hemX | P09127 | Putative uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase | 1 | 42.9 | 4.68 | 45.08 | 4.59 | 1.93 | 1.93 |

| 7 | imp | P31554 | Lipopolysaccharide assembly protein | om | 89.7/87.1 | 4.94/4.85 | 91.39 | 4.87 | 0.50 | 0.01 |

| 8 | yaeT | P0A940 | Outer membrane protein assembly factor YaeT | om | 90.6/88.4 | 4.93/4.87 | 88.4 | 4.87 | 0.33 | 0.62 |

| 12 | fadL | P10384 | Long-chain fatty acid transport protein | om | 48.5/45.9 | 5.09/4.91 | 44.86 | 4.84 | 1.03 | 1.17 |

| 14 | nlpB | P0A903 | Lipoprotein 34 | om lp | 36.9/34.4 | 5.34/4.96 | 34.68 | 4.74 | 0.52 | 1.01 |

| 15 | metQ | P28635 | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | om/im lp | 29.5/27.2 | 5.13/4.93 | 26.94 | 4.76 | 0.07 | ND |

| 16 | tsx | P0A927 | Nucleoside-specific channel-forming protein Tsx | om | 33.6/31.4 | 5.07/4.87 | 27.47 | 4.86 | 0.61 | 1.25 |

| 17 | ybaY | P77717 | Hypothetical lipoprotein YbaY | om/im lp | 19.5/17.7 | 7.88/6.31 | 23.21 | 4.78 | 0.44 | ND |

| 19 | mdtE | P37636 | Multidrug resistance protein MdtE | im lp | 41.2/38.9 | 5.73/5.12 | 40.1 | 4.97 | 0.31 | ND |

| 20 | tsx | P0A927 | Nucleoside-specific channel-forming protein Tsx | om | 33.6/31.4 | 5.07/4.87 | 27.54 | 4.96 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 21 | mipA | P0A908 | MltA-interacting protein | om | 27.8/25.7 | 5.50/5.03 | 25.74 | 4.95 | 0.26 | 0.64 |

| 23 | ompX | P0A917 | Outer membrane protein X | om | 18.6/16.4 | 6.56/5.3 | 16.12 | 4.91 | 0.49 | 1.13 |

| 24 | cirA | P17315 | Colicin I receptor | om | 74.1/71.2 | 5.11/5.03 | 75.78 | 5.05 | 0.11 | 0.77 |

| 25 | yiaF | P0ADK0 | Hypothetical protein YiaF | amb | 30.43 | 9.35 | 23.57 | 5.01 | 0.21 | 0.91 |

| 26 | fhuA | P06971 | Ferrichrome iron receptor | om | 82.4/78.7 | 5.47/5.13 | 79.29 | 5.16 | 0.32 | 0.77 |

| 27 | btuB | P06129 | Vitamin B12 transporter BtuB | om | 68.4/66.3 | 5.23/5.10 | 66.13 | 5.13 | 0.48 | 1.02 |

| 28 | tolC | P02930 | Outer membrane protein TolC | om | 53.7/51.5 | 5.46/5.23 | 52.68 | 5.13 | 0.50 | 0.78 |

| 29 | nlpA | P04846 | Lipoprotein 28 | im lp | 29.4/27.1 | 5.77/5.29 | 26.64 | 5.12 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| 30 | mipA | P0A908 | MltA-interacting protein | om | 27.8/25.7 | 5.50/5.03 | 25.52 | 5.11 | 0.49 | 1.02 |

| 32 | pal | P0A912 | Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein | om lp | 16.9/16.6 | 6.29/5.59 | 17.65 | 5.08 | 1.02 | 1.14 |

| 33 | fepA | P05825 | Ferrienterobactin receptor | om | 82.1/79.8 | 5.39/5.23 | 81.97 | 5.23 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| 34 | yfiO | P0AC02 | Lipoprotein YfiO | om lp | 27.9/25.8 | 6.16/5.48 | 24.87 | 5.2 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| 35 | ompX | P0A917 | Outer membrane protein X | om | 18.6/16.4 | 6.56/5.3 | 15.7 | 5.25 | 0.64 | 0.72 |

| 36 | pal | P0A912 | Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein | om lp | 16.9/16.6 | 6.29/5.59 | 17.43 | 5.38 | 1.19 | 1.12 |

| 41 | yfiO | P0AC02 | Lipoprotein YfiO | om lp | 27.9/25.8 | 6.16/5.48 | 25.39 | 5.53 | 0.69 | ND |

| 42 | ompW | P0A915 | Outer membrane protein W | om | 22.9/20.9 | 6.03/5.58 | 21.5 | 5.54 | 0.31 | 0.10 |

| 43 | fusA | P0A6M8 | Elongation factor G | c | 77.6 | 5.24 | 83.22 | 5.69 | 0.09 | ND |

| 44 | yicH | P31433 | Hypothetical protein YicH | sec | 62.3/58.7 | 5.67/5.38 | 63.8 | 5.85 | 0.15 | ND |

| 45 | ompA | P0A910 | Outer membrane protein A | om | 37.2/35.2 | 5.99/5.60 | 31.74 | 6 | 1.22 | 1.12 |

| 48 | ompX | P0A917 | Outer membrane protein X | om | 18.6/16.4 | 6.56/5.3 | 16.49 | 6.19 | 0.37 | 0.46 |

The spots in 2D gels of the outer membrane fraction from SecE-depleted and control cells were excised from gels stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue (Fig. 5A). Proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF. Spots visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining and phosphorimaging (Fig. 5A and B) were quantified and compared using PDQuest. Quantities of Coomassie brilliant blue-stained spots were normalized using the “total quantity of valid spot” tool, excluding spots detected in the 2D gels of protein aggregates extracted from the outer membrane fraction (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Quantities of spots visualized by phosphorimaging were normalized using the normalization factor calculated for the corresponding Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel. Changes of 0.01- and 100-fold correspond to spots that are missing (“off response”) and spots that are turned on (“on response”) in the SecE-depleted cells, respectively. Significant changes (P < 0.05) are indicated by bold type. Graphs of changes are shown in Fig. 5C.

The numbers correspond to the spot numbers in the 2D gels shown in Fig. 5A and B.

Gene designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Protein designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Localization based on the information given in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli. Unknown localizations were predicted by PSORT (http://psort.hgc.jp/form.html). Abbreviations: amb, ambiguous; c, cytoplasmic; im lp, inner membrane lipoprotein; om, outer membrane; om lp, outer membrane lipoprotein; sec, secretory.

Protein sizes predicted from amino acid sequences. Two sizes are given for secretory proteins; the first size is the size of the precursor form including the signal sequence, and the second size is the size of the mature form of the protein after signal sequence processing.

pIs predicted from amino acid sequences. Two values are given for secretory proteins; the first value is the pI for the precursor form, and the second value is the pI for the mature form of the protein.

Sizes of proteins calculated from the spot positions on the 2D gels shown in Fig. 5.

pIs of proteins calculated from the spot positions on the 2D gels shown in Fig. 5.

Changes expressed as the ratio of the average spot intensities. ND, not determined.

Inner membrane proteome.

MS analysis identified proteins in 76 spots on the Coomassie brilliant blue-stained 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels. Twenty-one additional spots were annotated with the help of our previously published reference map (Fig. 6A and B and Table 4; see Table S4 in the supplemental material) (67). Fifty-three proteins were integral membrane proteins, and 27 proteins were proteins located at the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane, mostly as part of membrane-localized complexes. In addition, five secretory proteins were identified in the 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels.

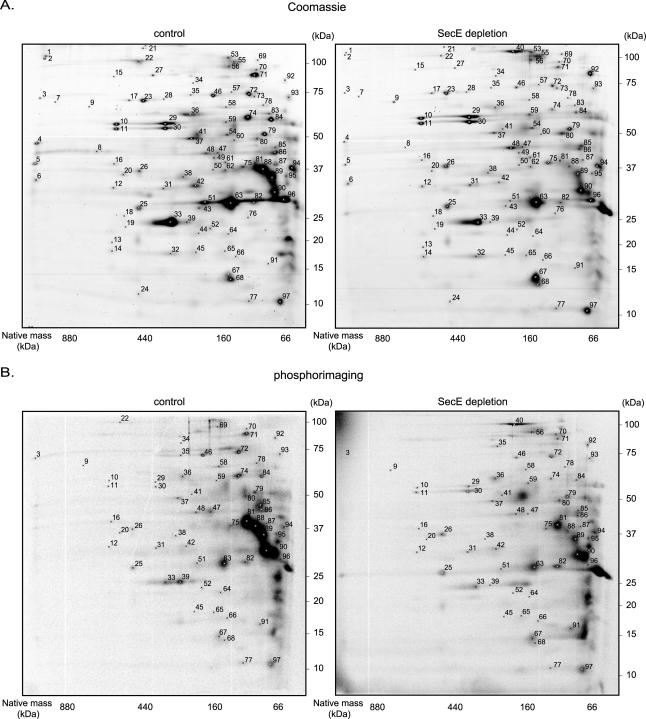

FIG. 6.

2D BN/SDS-PAGE analysis of the inner membrane proteomes of SecE-depleted and control cells. Cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 1 min, which was followed by a chase for 10 min with cold methionine. The inner membrane fractions were isolated by density centrifugation from a mixture of labeled and nonlabeled cells as outlined in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material (see Materials and Methods for details). The inner membrane fractions were analyzed by 2D BN/SDS-PAGE. Proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF (Table 4; see Table S4 in the supplemental material) using spots excised from Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gels. If several proteins were identified in one spot, the first gene listed corresponds to the protein with the highest Mascot MOWSE score. Primary gene designations were obtained from Swiss-Prot (www.expasy.org). Differences in the inner membrane proteomes of SecE-depleted and control cells were analyzed using PDQuest. Significantly affected (P < 0.05) proteins are indicated in Table 4 and in Table S4 in the supplemental material. (A) Representative 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels with proteins detected by staining with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue (protein steady-state levels). (B) Representative 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels with proteins detected by phosphorimaging (protein insertion). (C) Graph showing the changes (average spot intensities for SecE-depleted samples/average spot intensities for control samples) for proteins detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (black bars) and phosphorimaging (gray bars). A change of 100-fold indicates a spot that was detected only in SecE-depleted samples (“on response”), and a change of 0.01-fold indicates that a spot was detected only in the control samples (“off response”). The numbers correspond to spots on the gels in panels A and B.

TABLE 4.

2D BN/SDS-PAGE analysis of the inner membrane proteome of SecE-depleted and control cellsa

| Spotb | Genec | Protein

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation or functiond | Localization or no. of transmembrane segmentse | Predicted mol wt (103) (precursor/mature)f | Observed mol wt (103)g | Observed native mol wt (103)h | Coomassie brilliant blue change (fold) (SecE depleted/control)i | Phosphorimaging change (fold) (SecE depleted/control)i | ||

| 1 | yjeP | Hypothetical MscS family protein YjeP | 10 | 124.0 | 103.7 | 1,000 | 0.52 | ND |

| 2 | kefA | Potassium efflux system KefA | 11 | 127.2 | 100.7 | 1,000 | 0.23 | ND |

| 3 | ftsH | Cell division protease FtsH | 2 | 70.7 | 69.3 | 1,000 | 0.24 | 0.56 |

| 4 | hflK | HflK | 1 | 45.5 | 45.4 | 1,000 | 0.31 | ND |

| 5 | hflC | HflC | 1 | 37.7 | 37.4 | 1,000 | 0.43 | ND |

| 6 | ybbK | Hypothetical protein YbbK | 1 | 33.7 | 32.2 | 1,000 | 1.36 | ND |

| 6 | corA | Magnesium transport protein CorA | 2 | 36.6 | 32.2 | 1,000 | 1.36 | ND |

| 7 | nuoC | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit C/D | c, im ass | 68.7 | 67.1 | 966 | 0.70 | ND |

| 8 | creD | Inner membrane protein CreD | 6 | 49.8 | 42.7 | 733 | 0.20 | ND |

| 8 | hemY | HemY | 2 | 45.2 | 42.7 | 733 | 0.20 | ND |

| 9 | groL | 60-kDa chaperonin | c | 57.2 | 64.0 | 828 | 3.72 | 1.30 |

| 10 | atpA | ATP synthase subunit alpha | c, im ass | 55.2 | 55.4 | 638 | 1.36 | 0.91 |

| 11 | atpD | ATP synthase subunit beta | c, im ass | 50.2 | 53.0 | 637 | 1.50 | 1.44 |

| 12 | atpG | ATP synthase gamma chain | c, im ass | 31.6 | 31.4 | 614 | 1.19 | 1.49 |

| 13 | atpH | ATP synthase delta chain | c, im ass | 19.3 | 20.8 | 606 | 1.11 | ND |

| 14 | atpF | ATP synthase B chain | 1 | 17.3 | 18.9 | 599 | 1.47 | ND |

| 15 | fadE | Acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase | 2 | 89.2 | 85.1 | 600 | 1.28 | ND |

| 15 | plsB | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | c, im ass | 91.3 | 85.1 | 600 | 1.28 | ND |

| 16 | wzzE | Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis protein WzzE | 2 | 39.6 | 38.6 | 603 | 0.90 | 0.72 |

| 17 | nuoC | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit C/D | c, im ass | 68.7 | 68.1 | 543 | 0.86 | ND |

| 18 | nuoB | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit B | c, im ass | 25.1 | 25.5 | 510 | 0.59 | ND |

| 19 | nuoI | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit I | c, im ass | 20.5 | 23.5 | 509 | 0.84 | ND |

| 20 | wzzB | Chain length determinant protein | 2 | 36.5 | 35.1 | 531 | 0.55 | 0.07 |

| 21 | narG | Respiratory nitrate reductase 1 alpha chain | c, im ass | 140.4 | 113.1 | 463 | 1.92 | ND |

| 22 | acrB | Lavine resistance protein B | 12 | 113.6 | 92.7 | 478 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| 23 | sdhA | Succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit | c, im ass | 64.4 | 68.6 | 440 | 0.92 | ND |

| 24 | sdhD | Succinate dehydrogenase hydrophobic membrane anchor subunit | 4 | 12.9 | 12.0 | 427 | 0.94 | ND |

| 25 | sdhB | Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur subunit | c, im ass | 26.8 | 27.2 | 438 | 1.44 | 1.14 |

| 25 | manZ | Mannose permease IID component | 1 | 31.3 | 27.2 | 438 | 1.44 | 1.14 |

| 26 | manX | Phosphotransferase system mannose-specific EIIAB component | c, im ass | 34.9 | 36.8 | 439 | 2.40 | 1.26 |

| 27 | yrbD | Hypothetical protein YrbD | sec | 19.6/16.5 | 87.5 | 426 | 0.36 | ND |

| 28 | nuoC | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit C/D | c, im ass | 68.7 | 69.3 | 363 | 0.81 | ND |

| 29 | atpA | ATP synthase subunit alpha | c, im ass | 55.2 | 56.4 | 366 | 1.02 | 0.83 |

| 30 | atpD | ATP synthase subunit beta | c, im ass | 50.2 | 54.0 | 364 | 1.33 | 1.26 |

| 31 | atpG | ATP synthase gamma chain | c, im ass | 31.6 | 32.2 | 348 | 1.68 | 1.73 |

| 32 | atpF | ATP synthase B chain | 1 | 17.3 | 19.5 | 301 | 1.27 | ND |

| 33 | mscS | Small-conductance mechanosensitive channel | 3 | 30.9 | 24.4 | 302 | 0.77 | 0.94 |

| 34 | aas | AAS bifunctional protein | 2 | 80.7 | 78.7 | 248 | 4.38 | 1.59 |

| 34 | yhjG | Hypothetical protein YhjG | 2 | 75.1 | 78.7 | 248 | 4.38 | 1.59 |

| 35 | ppiD | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase D | 1 | 68.2 | 71.6 | 264 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| 36 | msbA | Lipid A export ATP-binding/permease protein MsbA | 5 | 64.5 | 59.7 | 238 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| 37 | hemX | Putative uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase | 1 | 43.0 | 49.0 | 265 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| 38 | ydjN | Hypothetical symporter YdjN | 9 | 48.7 | 35.1 | 272 | 0.98 | 0.69 |

| 39 | exbB | Biopolymer transport ExbB protein | 3 | 26.3 | 24.7 | 243 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| 40 | secA | Preprotein translocase subunit SecA | c, im ass | 102.0 | 108.1 | 209 | 50.77 | 100.00 |

| 41 | cyoB | Ubiquinol oxidase subunit 1 | 15 | 74.4 | 50.7 | 203 | 0.15 | 0.81 |

| 42 | cyoA | Ubiquinol oxidase subunit 2 | 2 | 34.9 | 32.6 | 201 | 0.25 | 0.79 |

| 43 | yhbG | Probable ABC transporter ATP-binding protein YhbG | c, im ass | 26.7 | 27.5 | 201 | 0.35 | ND |

| 44 | ygiM | Hypothetical protein YgiM | 1 | 23.1 | 22.6 | 218 | 0.31 | ND |

| 44 | tolQ | TolQ | 3 | 25.6 | 22.6 | 218 | 0.31 | ND |

| 45 | atpF | ATP synthase B chain | 1 | 17.3 | 20.1 | 200 | 0.11 | 0.88 |

| 46 | ppiD | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase D | 1 | 68.2 | 71.4 | 176 | 0.51 | 0.59 |

| 47 | dacC | Penicillin-binding protein 6 | 1* | 43.6/40.8 | 42.6 | 158 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

| 47 | mdtE | Multidrug resistance protein MdtE | im, lp | 41.2 | 42.6 | 158 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

| 47 | cysA | Sulfate/thiosulfate import ATP-binding protein CysA | c, im ass | 41.1 | 42.6 | 158 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

| 48 | cysA | Sulfate/thiosulfate import ATP-binding protein CysA | c, im ass | 41.1 | 43.1 | 177 | 2.27 | 1.37 |

| 48 | dacC | Penicillin-binding protein 6 | 1* | 41.1 | 43.1 | 177 | 2.27 | 1.37 |

| 48 | hemY | HemY | 2 | 45.2 | 43.1 | 177 | 2.27 | 1.37 |

| 49 | dacA | Penicillin-binding protein 5 | 1* | 44.4/41.3 | 41.4 | 1.40 | ND | |

| 49 | dppF | Dipeptide transport ATP-binding protein DppF | c, im ass | 37.6 | 41.4 | 160 | 1.40 | ND |

| 50 | dppD | Dipeptide transport ATP-binding protein DppD | c, im ass | 35.8 | 37.3 | 160 | 1.70 | ND |

| 51 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im/om lp | 29.4/27.2 | 29.0 | 166 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

| 51 | nlpA | Lipoprotein 28 | im/om lp | 29.4/27.1 | 29.0 | 166 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

| 52 | yfgM | YfgM | 1 | 22.2 | 23.7 | 165 | 0.41 | 0.66 |

| 53 | nuoG | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit F | c, im ass | 100.2 | 102.5 | 159 | 1.30 | ND |

| 54 | nuoF | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit G | c, im ass | 49.3 | 51.1 | 150 | 0.95 | ND |

| 55 | mgtA | Magnesium-transporting ATPase, P-type 1 | 10 | 99.5 | 98.6 | 149 | 1.34 | ND |

| 56 | copA | Copper-transporting P-type ATPase | 8 | 87.7 | 93.4 | 158 | 0.90 | 1.44 |

| 56 | mrcA | Penicillin-binding protein 1A | 1 | 93.6 | 93.4 | 158 | 0.90 | 1.44 |

| 57 | frdA | Fumarate reductase flavoprotein subunit | c, im ass | 65.8 | 74.2 | 145 | 1.24 | ND |

| 58 | secD | Protein-export membrane protein SecD | 6 | 66.6 | 65.5 | 151 | 0.47 | 0.60 |

| 59 | cydC | Transport ATP-binding protein CydC | 6 | 62.9 | 57.5 | 150 | 1.86 | 1.79 |

| 59 | cydD | Transport ATP-binding protein CydD | 6 | 65.1 | 57.5 | 150 | 1.86 | 1.79 |

| 60 | cydA | Cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit 1 | 7 | 58.2 | 48.1 | 137 | 0.19 | ND |

| 61 | metN | Methionine import ATP-binding protein MetN | c | 37.8 | 40.4 | 147 | 1.41 | ND |

| 62 | degS | Protease DegS | p | 37.6/34.6 | 37.7 | 151 | 0.45 | ND |

| 63 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im/om lp | 29.4/27.2 | 29.1 | 135 | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| 64 | rnfG | Electron transport complex protein RnfG | 1 | 21.9 | 22.6 | 143 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| 65 | atpF | ATP synthase B chain | 1 | 17.3 | 20.1 | 149 | 2.07 | 1.25 |

| 66 | glnP | Glutamine transport system permease protein GlnP | 5 | 24.4 | 19.0 | 128 | 0.83 | 0.92 |

| 67 | yhcB | Putative cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit III | 1 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 144 | 2.41 | 1.52 |

| 68 | yhcB | Putative cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit III | 1 | 15.2 | 14.6 | 133 | 1.05 | 0.90 |

| 69 | ydiJ | Hypothetical protein YdiJ | amb | 113.2 | 103.2 | 115 | 2.27 | ND |

| 70 | plsB | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | c, im ass | 91.3 | 94.4 | 116 | 0.91 | 1.31 |

| 71 | gcd | Quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase | 5 | 86.7 | 89.7 | 117 | 0.41 | 0.66 |

| 72 | ppiD | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase D | 1 | 68.2 | 73.1 | 126 | 0.68 | 0.99 |

| 73 | nuoC | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit C/D | c, im ass | 68.7 | 72.2 | 119 | 0.96 | ND |

| 74 | oxaA | Inner membrane protein OxaA | 6 | 61.5 | 60.6 | 125 | 0.31 | 0.42 |

| 75 | ybhG | Membrane protein YbhG | 1 | 36.4/34.4 | 37.9 | 130 | 0.56 | 1.17 |

| 76 | nuoB | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit B | c, im ass | 25.1 | 26.5 | 119 | 1.17 | ND |

| 77 | yajC | Membrane protein YajC | 1 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 111 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| 78 | secD | Protein export membrane protein SecD | 6 | 66.6 | 67.5 | 106 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| 78 | yicH | Hypothetical protein YicH | amb | 62.3 | 67.5 | 106 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| 79 | dadA | d-Amino acid dehydrogenase small subunit | c, im ass | 47.6 | 52.2 | 105 | 1.04 | 1.07 |

| 79 | zip | Cell division protein ZipA | 1 | 36.5 | 52.2 | 105 | 1.04 | 1.07 |

| 80 | ndh | NADH dehydrogenase | amb | 47.2 | 49.3 | 111 | 1.63 | 1.36 |

| 81 | proP | Proline/betaine transporter | 12 | 54.8 | 41.7 | 111 | 0.62 | 0.85 |

| 82 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im/om lp | 29.4/27.2 | 29.1 | 110 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| 83 | yijP | Membrane protein YijP | 5 | 66.6 | 62.9 | 96 | 0.45 | ND |

| 84 | ydgA | Protein YdgA | p, im ass | 54.7/52.8 | 59.3 | 96 | 0.42 | 0.66 |

| 85 | emrA | Multidrug resistance protein A | 1 | 42.7 | 45.5 | 89 | 0.86 | 0.72 |

| 86 | dacA | Penicillin-binding protein 5 | 1* | 44.4/41.3 | 43.6 | 92 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| 86 | dacC | Penicillin-binding protein 6 | 1* | 43.6/40.8 | 43.6 | 92 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| 87 | pyrD | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase | c, im ass | 36.8 | 39.4 | 83 | 0.37 | 0.10 |

| 88 | gadC | Probable glutamate/gamma-aminobutyrate antiporter | 12 | 55.1 | 38.3 | 98 | 0.27 | 0.70 |

| 89 | glpT | Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter | 12 | 47.2 | 50.3 | 87 | 0.54 | 0.42 |

| 90 | ompA | Outer membrane protein A | om | 37.2 | 31.8 | 87 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| 90 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im/om lp | 29.4/27.2 | 31.8 | 87 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| 91 | pgsA | CDP-diacylglycerol-glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyltransferase | 4 | 20.6 | 17.2 | 86 | 1.83 | 1.73 |

| 92 | dnaK | Chaperone protein DnaK | c | 69.0 | 83.7 | 77 | 5.89 | 1.72 |

| 93 | dld | d-Lactate dehydrogenase | c, im ass | 64.5 | 73.3 | 71 | 0.72 | 1.15 |

| 94 | cysK | Cysteine synthase A | c | 34.4 | 38.1 | 63 | 1.10 | 0.86 |

| 95 | lepB | Signal peptidase I | 2 | 36.0 | 35.2 | 69 | 0.50 | 0.95 |

| 96 | metQ | d-Methionine-binding lipoprotein MetQ | im/om lp | 29.4/27.2 | 29.5 | 70 | 0.39 | ND |

| 96 | rpsB | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | c | 26.6 | 29.5 | 70 | 0.39 | ND |

| 97 | yajC | Membrane protein YajC | 1 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 71 | 1.44 | 1.43 |

Spots in 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels of inner membranes (Fig. 6A) were excised from gels stained with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue. Proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PMF. The proteins encoded by the following genes belonged to the same complex: ftsH, hflK, and hflC (spots 3 to 5); atpA, atpD, atpG, atpH, and atpF (spots 10 to 14); nuoC, nuoB, and nuoI (spots 17 to 19); sdhA, sdhD, and sdhB (spots 23 to 25); manZ and manX (spots 25 and 26); atpA, atpD, atpG, and atpF (spots 29 to 32); cyoB and cyoA (spots 41 and 42); dppF and dppD (spots 49 and 50); nuoG and nuoF (spots 53 and 54); and cydC and cydD (spot 59). Spots visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining and/or phosphorimaging (Fig. 6A and B) were quantified and compared using PDQuest. Changes of 0.01- and 100-fold correspond to spots that are missing (“off response”) and spots that are turned on (“on response”) in the SecE-depleted cells, respectively. Significant changes (P < 0.05) are indicated by bold type.

The numbers correspond to the spots in the 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels shown in Fig. 6A.

Gene designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Protein designations in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli.

Localization based on the information given in the Swiss-Prot database for E. coli. Unknown localizations were predicted by PSORT. For integral membrane proteins, the number of transmembrane segments is indicated. An asterisk indicates that the membrane-inserted segment may act as an anchor rather than as a true transmembrane segment. Abbreviations: amb, ambiguous; c, cytoplasmic; im ass, inner membrane associated; im lp, inner membrane lipoprotein; om, outer membrane; om lp, outer membrane lipoprotein; sec, secretory.

Protein sizes predicted from amino acid sequences. Two sizes are given for secretory proteins; the first size is the size of the precursor form, and the second size is the size of the mature form of the protein.

Sizes of proteins calculated from the spot positions on the 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gels used for the analysis.

Native molecular weights based on the positions in the 2D BN/SDS-PAGE gel in Fig. 6A.

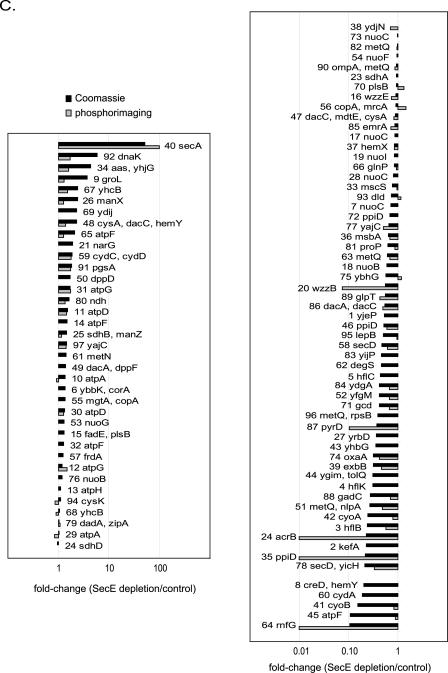

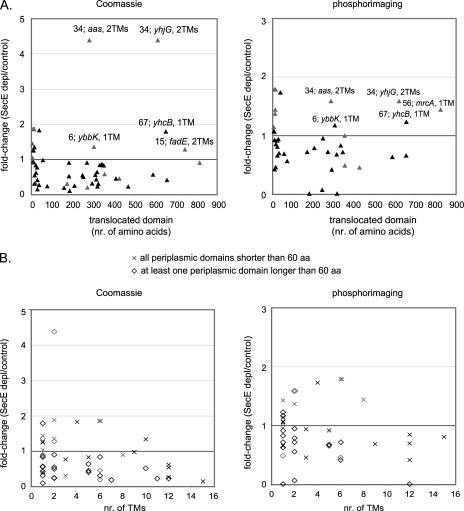

Changes expressed as the ratio of the average intensity of spots in gels of the SecE-depleted cells to the average intensity of matched spots in the control gels. ND, not determined.