Abstract

YgaF, a protein of previously unknown function in Escherichia coli, was shown to possess noncovalently bound flavin adenine dinucleotide and to exhibit l-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidase activity. The inability of anaerobic, reduced enzyme to reverse the reaction by reducing the product α-ketoglutaric acid is explained by the very high reduction potential (+19 mV) of the bound cofactor. The likely role of this enzyme in the cell is to recover α-ketoglutarate mistakenly reduced by other enzymes or formed during growth on propionate. On the basis of the identified function, we propose that this gene be renamed lhgO.

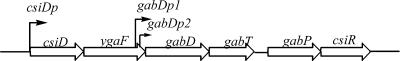

The ygaF gene of Escherichia coli is located immediately downstream of csiD, which encodes a crystallographically characterized protein of unknown function (4), and just upstream of the gabDTP operon and csiR, which encode succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase, a GABA-specific permease, and a repressor (Fig. 1). The first five genes, and perhaps all six (30), are coregulated by CsiR repression and cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein and σs induction acting at csiDp during carbon starvation and at stationary phase (14, 18). Expression of gabDTP is additionally controlled by σs binding to gabDp1, which is triggered by multiple-stress induction (18), and by Nac/σ70 interaction with gabDp2 in response to nitrogen starvation (30). YgaF is not obviously involved in GABA metabolism (30), and its role is unknown.

FIG. 1.

Location of ygaF and regulation of the csiD-ygaF-gabDTP-csiR gene cluster. The gene that encodes YgaF is positioned downstream of and is coregulated with csiD, in part through the action of CsiR. Although located immediately upstream of the gabDTP operon, it is not involved in GABA metabolism.

On the basis of its amino acid sequence, YgaF is likely to be a flavoenzyme. It has been estimated that 1 to 3% of the identified proteins in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells contain flavin (5) and these abundant enzymes catalyze a wide range of reactions with a diverse set of substrates, including alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, amines, dithiols, amino acids, and hydroxy acids (34). Most of these enzymes transition between the fully oxidized and two-electron reduced forms of their cofactor, but in some cases, the one-electron reduced semiquinone species is stabilized. Reoxidation of the reduced flavin coenzyme can take place via several processes, including the reaction with oxygen, as in the case of flavin oxidases. The flavin cofactors (generally, flavin mononucleotide [FMN] or flavin adenine dinucleotide [FAD]) often are tightly bound to these enzymes, and in selected examples, the coenzyme is covalently attached to the protein (11). Sequence comparisons of YgaF reveal this 422-amino-acid E. coli protein to be homologous to human mitochondrial l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (41% identity over 398 residues) (28), Helicobacter pylori malate:quinone oxidoreductase (24% identity over 421 residues) (33), Bacillus sp. strain B-0618 creatinase and sarcosine oxidase (23% identity over 255 residues) (32), human mitochondrial dimethylglycine dehydrogenase (24% identity over 227 residues) (2), Bacillus subtilis glycine oxidase (25% identity over 146 residues) (9), human peroxisomal l-pipecolic acid oxidase (21% identity over 219 residues) (6), and many other flavoenzymes. This list includes both dehydrogenases and oxidases, and some representatives have covalently bound flavin (6, 7, 12) while others do not. Here, we describe the cloning and overexpression of ygaF, the purification and characterization of the encoded protein, and the demonstration that it is an oxidase that possesses noncovalently bound FAD. Moreover, we show that YgaF is an l-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidase and we discuss the potential relevance of this activity to E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

l-2-Hydroxyglutarate, as its zinc salt, was obtained from City Chemicals LLC (West Haven, CT). d-2-Hydroxyglutarate (disodium salt) and 3-phospho-d-glycerate were from Sigma-Aldrich. S-5-Amino-2-hydroxyvalerate and R-5-amino-2-hydroxyvalerate were synthesized from l-ornithine and d-ornithine · HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by following a previously published procedure (31).

Cloning and expression of ygaF.

The gene that encodes YgaF was amplified by PCR with E. coli MG1655 DNA as the template, Pfu polymerase, and primers (5′-CAA AGG AAT TGA GCA TAT GTA TGA TTT TG-3′ and 5′-GCT ACA TCC TGT TTT CAA AAG CTT TTG ATT AAA TGC GGC GTG-3′) that introduce NdeI and HindIII sites into the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene, respectively. Ligation of the 1,269-bp NdeI- and HindIII-digested PCR product into pET42b (Novagen) provided a region that encodes an in-frame C-terminal His6 tag. The ligation reaction products were transformed into MAX Efficiency E. coli DH5α competent cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the resulting pET42b-ygaF plasmid was transformed into E. coli C41(DE3) cells (20) and BL21(DE3) cells.

The transformants were plated onto Luria broth agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. A single colony was used to inoculate 50 ml of Luria broth medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin, and the culture was grown overnight at 37°C. A portion (15 ml) of the overnight growth was used to inoculate 1 liter of Terrific broth (Fisher Biotech) containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin, and this was incubated at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added (1 mM final concentration), and the growth continued at 30°C overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,500 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 30 ml of lysis buffer (30 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 20% glycerol, 50 μM FAD, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.2). Cells were broken by sonication (Branson Sonifier, five repetitions, each of 1 min, at 30 W of output power and 50% duty cycle) and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C.

Purification of His-tagged YgaF.

The cell extracts were loaded onto a Ni-charged nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)-Sepharose 6 fast-flow column (2 cm in length by 2.5 cm in diameter; GE Healthcare) which had been equilibrated with buffer A (30 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 20% glycerol, pH 7.2). The column was washed with buffer B (100 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 20% glycerol, pH 7.2) in order to remove any weakly bound protein from the resin, and YgaF was eluted with buffer C (500 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 20% glycerol, pH 7.2). To enhance its stability, YgaF was immediately exchanged into buffer D (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 20% glycerol, pH 8.2) by using a Superdex G-25 column that had been equilibrated with this buffer. The fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with a 12% polyacrylamide gel (10). Molecular weight markers included phosphorylase b, bovine serum albumin, ovalbumin, carbonic anhydrase, trypsin inhibitor, and lysozyme (97.4, 66.2, 45, 31, 21.5, and 14.4 kDa, respectively; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Protein concentrations were determined by use of the Bradford assay (3).

Spectroscopic studies.

Absorption spectra were obtained at room temperature with a Shimadzu UV-2401 UV/visible light spectrophotometer. For analyses requiring the absence of oxygen, anaerobic cuvettes (1 ml or 200 μl; Hellma, Plainview, NY) were used. YgaF was made anaerobic by 10 cycles of vacuum-argon flushing while keeping the protein on ice to avoid precipitation and reduce evaporation. In some cases, trace amounts of oxygen were eliminated from the buffers by including protocatechuic 3,4-dioxygenase (PCD) at 0.04 U/ml and its substrate protocatechuic acid (PCA) at 80 μM (both obtained from Sigma-Aldrich). Additives were prepared in sealed serum vials and similarly treated by alternate cycles of vacuum and argon flushing. Solutions were added with gas-tight syringes.

To assess whether the flavin chromophore was covalently attached to the enzyme, two approaches were used (1). In initial experiments, YgaF (600 μl of 23 μM enzyme) was treated for 1 h on ice in the dark with 10% trichloroacetic acid (19). After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min to separate the protein pellet from the solution, the spectrum of the protein-free sample was compared to that of the original enzyme solution. Because of concern that the acidic conditions in this first procedure may have hydrolyzed the native form of the flavin cofactor, a second experiment was performed in which the cofactor was released from YgaF by heat treatment at 100°C for 1 min in unbuffered water. The resulting solution was passed through a Centricon-10 ultrafilter (Millipore) to remove the protein. Matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization mass spectrometry (MS) was used to identify the flavin released from enzyme by the trichloroacetic acid and thermal treatments. The samples were mixed with a matrix containing 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid and analyzed with an Applied Biosystems Voyager System 4148.

The effect of dithionite on the YgaF spectrum was examined. Anaerobic YgaF (10 μM in 25 mM HEPES [pH 8.2] buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol) in a 200-μl cuvette was made anaerobic by successive vacuum-argon filling cycles, incubated with PCD and PCA for 10 min at 4°C to ensure the removal of all residual oxygen, and titrated with an anaerobic solution of sodium dithionite (2 mM). The reaction was monitored spectroscopically, and the fully reduced sample was mixed with an equal volume of buffer equilibrated with 100% oxygen. The concentration of dithionite was calibrated by titration of a solution of authentic FAD (Sigma-Aldrich).

Photoreduction of YgaF was analyzed. Anaerobic enzyme (40 μM) was incubated with PCD, PCA, and 5-deazaflavin (4 μM, generously provided by Dave Arscott) on ice for 10 min, adjusted to 30 mM EDTA, and exposed to light (with a 50-W halogen spotlight at a distance of 6 in.) at 4°C. Spectra were monitored over time. A similarly treated sample of enzyme (500 μl of a 66 μM concentration) was used to test the rate of reoxidation of reduced YgaF. The photoreduced protein was anaerobically transferred to a cuvette containing 2 ml of rapidly stirring air-saturated buffer D while monitoring the average absorbance in a range of 440 to 460 nm in a model USB4000 spectrophotometer (Ocean Optics). Preliminary tests with FMN demonstrated an approximately 500-ms mixing time with this setup.

The effect of sulfite addition on the spectrum of YgaF was investigated. YgaF was exchanged into a mixture of 25 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol, pH 7.0. Sodium sulfite (Baker Analyzed Reagents) was dissolved in the same buffer and used to titrate the enzyme (15 μM), allowing the mixtures to equilibrate for 2 min before monitoring their spectra. The dissociation constant (Kd) of sulfite was calculated by using the equation

|

(1) |

In this equation, ΔA is the observed change in absorbance at 450 nm, ΔAmax is the maximum change in absorbance, and [L] is the concentration of free ligand (in this case, sulfite).

Potential substrates were examined spectroscopically for the capacity to reduce the FAD (or oxidize the previously reduced FAD) of YgaF. Putative substrates were prepared as stock solutions (5 to 20 mM) in a mixture of 25 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol (pH 8.2) and made anaerobic by vacuum-argon cycling. To test whether these chemicals were capable of reducing the enzyme flavin, anaerobic YgaF in the same buffer was titrated with the test chemicals while monitoring the spectral changes. To test whether the compounds would oxidize the bound FAD in its reduced form, the anaerobic enzyme was first treated with sufficient dithionite to reduce the flavin and then titrated with the potential oxidants.

Fluorescence spectra were acquired with a SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Determination of the YgaF FAD redox potential.

The reduction potential of the FAD cofactor of YgaF was determined spectroscopically by reductive titration of a mixture of the protein and each of several redox dyes. The most useful indicators were methylene blue (MB) and phenazine methosulfate (PMS), with reduction potentials of −5 mV (23) and +65 mV (24), respectively, at pH 7.5. YgaF (10 μM) and the selected redox dye (10 μM) were placed into an anaerobic cuvette along with PCD in 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.5, containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol. The mixtures were degassed, and PCA was added to eliminate any traces of oxygen. The samples were titrated with freshly prepared dithionite (calibrated by titration of free FAD) while monitoring the changes in the spectrum after allowing time to achieve redox equilibration. The reduction potential of the system (E) was calculated by using the Nernst equation

|

(2) |

where Em is the midpoint potential of the redox dye, R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), T is the temperature in K, n is the number of electrons transferred, and F is the Faraday constant (96.5 J mV−1 mol−1). By plotting log([YgaFox]/[YgaFred]) versus E, the Em of the YgaF flavin was calculated.

OPDA assay.

A series of 2-hydroxy acid compounds were tested as substrates of YgaF by using ortho-phenylenediamine (OPDA), which is known to react with many α-keto acids (8), the potential products of the YgaF reaction. In addition, this reagent was used to determine the kinetic parameters of l-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidation in comparison with authentic α-ketoglutarate. For the latter experiments, a freshly prepared stock solution containing 10 mg OPDA in 10 ml of 1 M phosphoric acid was adjusted to pH 2 and 25 μl β-mercaptoethanol was added. Samples (7.76 ml) of 1 μM YgaF (in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol) were mixed with l-2-hydroxyglutarate (0 to 400 μM) and incubated at room temperature. At selected time points, aliquots (0.97 ml) were transferred to glass tubes containing OPDA (280 μl of 8.9 mM), which quenched the reactions. To monitor the amount of product generated, samples were boiled for 3 min and cooled and the absorbance at 340 nm was determined.

Oxygen electrode assay.

To assay any potential oxidase activity of YgaF, the enzyme was mixed with various compounds while monitoring O2 consumption with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH). The experiments were carried out at room temperature with air-saturated buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, pH 8.2), 2 μM YgaF, and the potential substrate at 1 mM in a 5-ml solution.

Organic acid high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis.

Reaction mixtures (1 ml) containing 1 μM enzyme and 500 μM l-2-hydroxyglutarate in a mixture of 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.2), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, and 2 mM DTT were incubated at room temperature for 4.5 h. Aliquots (300 μl) were quenched with 5 μl of 6 M sulfuric acid and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min, and 250-μl portions of each supernatant were filtered (Amicon ultrafree-MC from Millipore) at 10,000 × g for 1 min. Samples (200 μl) were analyzed by using a Waters Breeze HPLC system equipped with an organic acid column (Bio-Rad) that had been equilibrated with 13 mM sulfuric acid and monitoring the refractive index. The concentrations of l-2-hydroxyglutarate (eluting at 23.0 min) and α-ketoglutarate (20.1 min) were determined by comparison to standards.

RESULTS

Purification of YgaF.

YgaF containing a C-terminal His6 tag was purified by Ni-NTA-Sepharose 6 fast-flow chromatography from soluble extracts of E. coli C41(DE3) containing pET42b-ygaF. Immediately after elution, the protein was exchanged into imidazole-free buffer to enhance its stability. Glycerol, EDTA, and DTT further stabilized the protein (data not shown). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown) revealed the protein to be ∼95% homogeneous with a molecular mass in agreement with that predicted from the sequence (47.64 kDa for the His-tagged protein). A 1-liter culture typically provided 55 to 65 mg of YgaF after Ni-NTA-Sepharose column chromatography or 30 to 40 mg after Sephadex G-25 chromatography. Purified YgaF was stored in buffer D at 4°C, a condition under which activity was stable for several weeks.

Spectroscopic and MS analyses of YgaF.

Purified YgaF is yellow in color, and its spectrum (maxima at 378 and 450 nm with a shoulder at 476 nm) is consistent with that of a flavoprotein. To distinguish whether the flavin is covalently attached to YgaF, as has been reported for several sequence-related enzymes (6, 7, 12), the protein was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid or by heat treatment. The proteins were separated from the yellow supernatants, thus demonstrating that the cofactor is not covalently attached to YgaF. MS analysis of the sample obtained by acid denaturation revealed features at m/z 458.1 and 379.1, consistent with the values expected for FMN and riboflavin (data not shown). In contrast, the MS results of the heat-denatured sample were consistent with the YgaF cofactor being FAD (m/z 784.5), not FMN. FAD was expected on the basis of the sequence alignment of YgaF to dimethylglycine oxidase (a structurally characterized protein with PDB accession code 1pj5) and the observed conservation of residues that interact with the AMP portion of the cofactor. The presence of FAD was confirmed by measuring the fluorescence (450-nm excitation, 520-nm emission) of the released cofactor before and after treatment with phosphodiesterase (data not shown), where an 8.5-fold increase was observed to result from the conversion of FAD to FMN (13). These results indicate that long-term exposure to trichloroacetic acid leads to decomposition of the YgaF FAD, as previously noted for other enzymes (13).

Chemical reduction of YgaF with dithionite led to a smooth transition to the two-electron reduced species, requiring 1.6 equivalents of dithionite (data not shown). No anionic or neutral semiquinone species was observed during the titration. Similarly, photoreduction of YgaF in the presence of EDTA and 5-deazaflavin (15, 17) led directly to the fully reduced cofactor, with no semiquinone intermediate observed (data not shown). The addition of an equal volume of buffer equilibrated with 100% oxygen to dithionite-reduced enzyme led to the immediate reoxidation of the FAD to half of the starting spectral intensity, as expected for an oxidase. In an effort to better define the rate of reoxidation by oxygen, photoreduced YgaF was mixed with a fourfold volume of air-saturated buffer. The reduced enzyme was observed to reoxidize within the 500-ms mixing time of the experiment (data not shown), allowing estimation of the apparent second-order rate constant for reaction with oxygen of ≥23 mM−1 s−1.

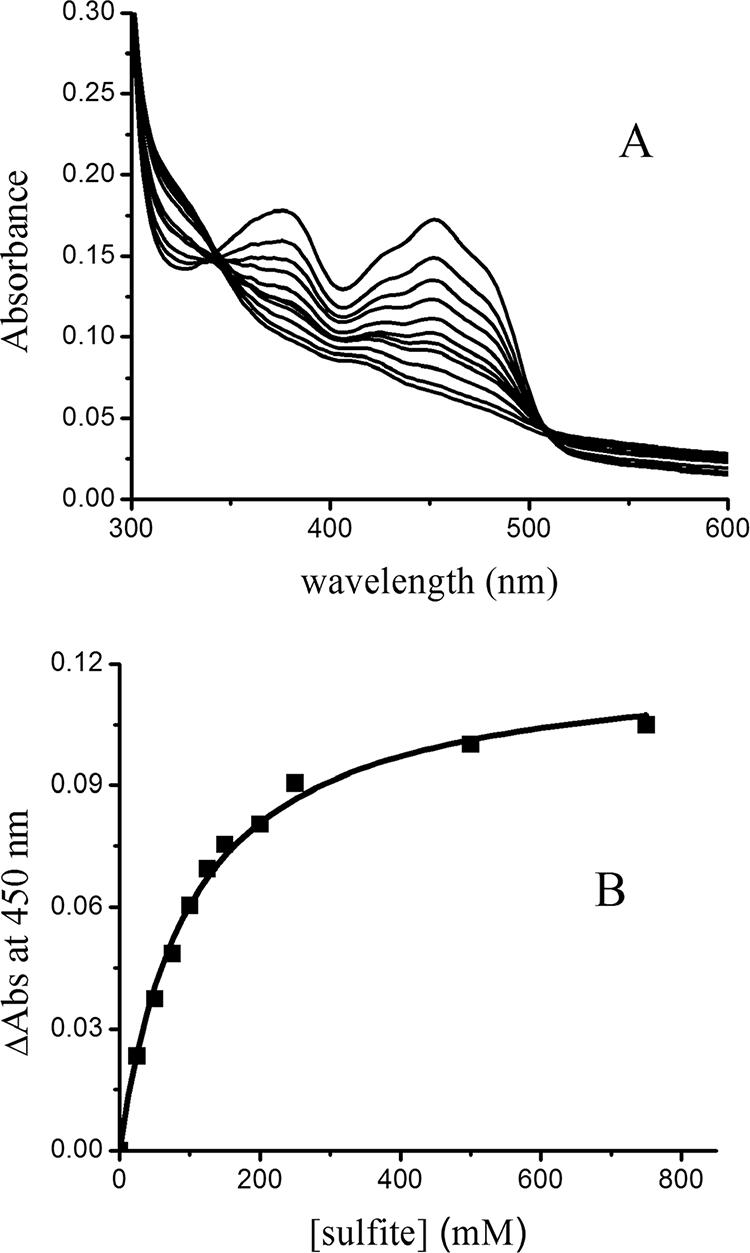

Many flavin-containing oxidases are bleached by the formation of a complex between sulfite and FAD (16). The addition of sulfite to YgaF resulted in loss of the FAD absorbance (Fig. 2A), providing a sulfite Kd of 102 ± 7 μM at pH 7 (Fig. 2B). A correlation has been noted (21) between the measured Kd of sulfite binding to oxidases and the enzyme redox potentials; extrapolation of those data allowed us to estimate the redox potential of the YgaF flavin as approximately −25 mV at pH 7, a relatively high potential compared to that of free flavin (−210 mV).

FIG. 2.

Titration of YgaF with sulfite. (A) YgaF (15 μM) was titrated with 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200, 250, 500, and 700 μM sulfite in 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol. (B) Absorbance change (ΔAbs) at 450 nm versus the concentration of free sulfite.

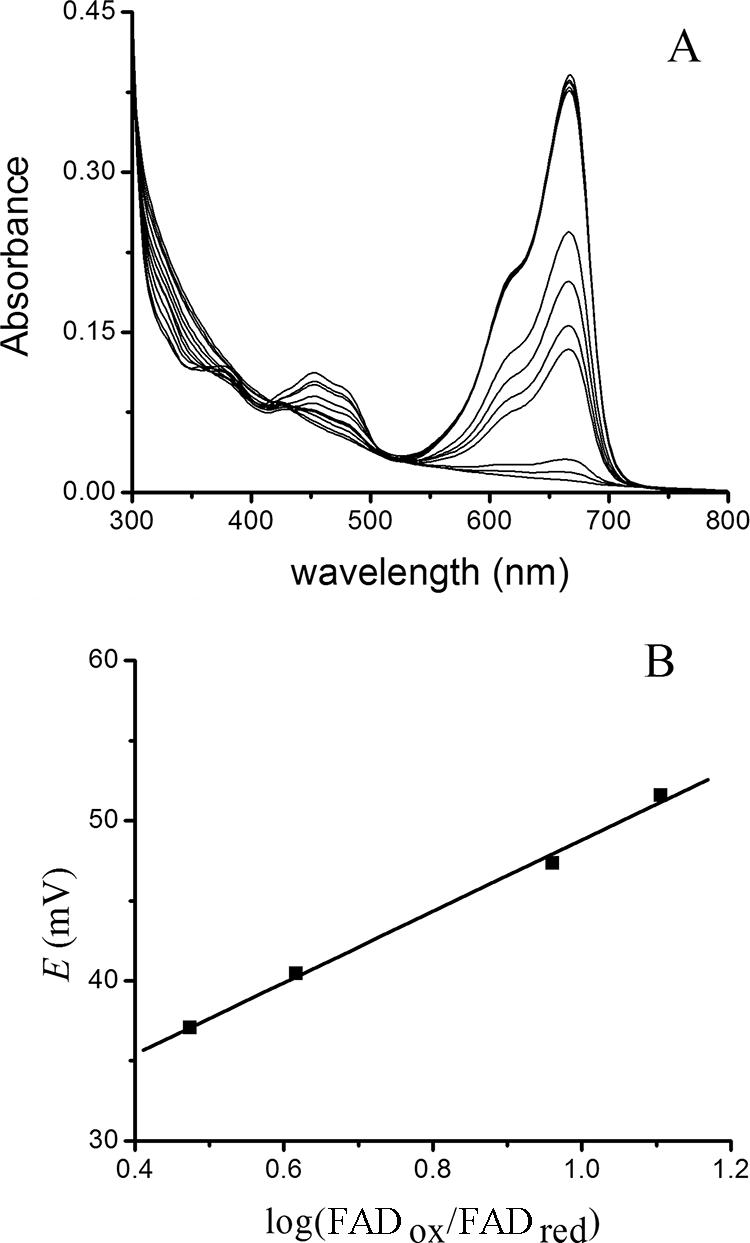

To more directly determine the reduction potential of the YgaF-bound FAD, reductive titrations were carried out in the presence of redox dyes. To illustrate, YgaF was mixed with MB (Em = −5 mV at pH 7.5), made anaerobic, and titrated with increasing levels of dithionite (Fig. 3A). By monitoring the concentration of oxidized MB (λmax = 666 nm with ɛ666 = 35,440 M−1 cm−1; its reduced form has essentially no absorbance at this wavelength) (22), the system reduction potential (E) after each addition could be determined by using equation 2. A comparison of E versus the log of the ratio of oxidized to reduced YgaF was used to determine an Em for YgaF of approximately +27 mV (Fig. 3B). Analogous studies (data not shown) were carried out with PMS (+65 mV at pH 7.5), which, upon reduction, exhibits a sharp absorption feature at 388 nm (ɛ388 = 21,390 M−1 cm−1). The Em for YgaF, calculated by using PMS, was approximately +11 mV. By taking into account both experiments, we conclude that the YgaF redox potential is 19 ± 8 mV.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of YgaF flavin reduction potential. (A) An anaerobic mixture of YgaF and MB (10 μM each) was titrated with sodium dithionite while monitoring the absorption spectrum. The changes in the relative concentrations of the reduced and oxidized forms of MB were used to deduce the system reduction potential (E) for each condition. (B) Correlation of E with the log(FADox/FADred) of YgaF.

Identification of substrates of YgaF.

Several compounds were tested as potential substrates of YgaF by assaying for the ability to (i) reduce FAD or oxidize the reduced FAD in anaerobic enzyme, (ii) stimulate oxygen consumption, or (iii) react with OPDA, a reagent for detecting α-keto acids. Significantly, neither the reduced nor the oxidized form of NAD+ or NADP+ affected the flavin spectrum; thus, YgaF is not a nicotinamide-dependent enzyme. No spectroscopic changes or O2 consumption activity was detected when YgaF was incubated with GABA or several compounds that could plausibly be used in GABA production (agmatine, putrescine, glutamic acid, glutamine, and the R and S isomers of 5-amino-2-hydroxyvaleric acid). Similarly, no activity was detected for selected methylated compounds (dimethylglycine, sarcosine), a representative aldehyde (butyraldehyde), or a 3-hydroxy acid (3-hydroxybutyric acid). Furthermore, most 2-hydroxy acids were ineffective as substrates, including l-malic acid, dl-malic acid, dl-lactic acid, l-mandelic acid, d-mandelic acid, and 2-hydroxycaproic acid. In contrast, robust activity was detected in the case of l-2-hydroxyglutaric acid.

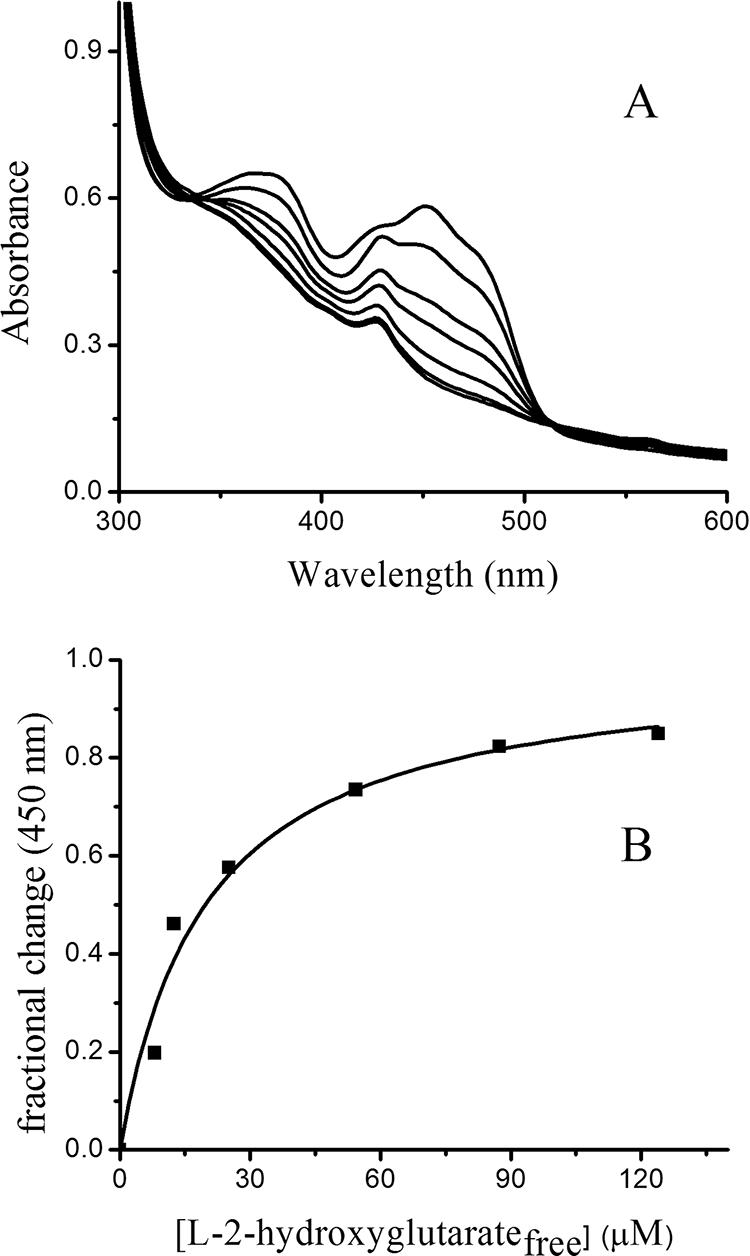

The behavior of l-2-hydroxyglutarate as a substrate of YgaF was examined in greater detail. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the addition of increasing concentrations of l-2-hydroxyglutarate to an anaerobic solution of YgaF resulted in successive reduction of the FAD (the feature at 410 nm was a contaminant in this particular preparation), with a fully reduced sample requiring about 1.5 equivalents of substrate. Analysis of the concentration-dependent changes in the difference spectra by use of equation 1 yielded an l-2-hydroxyglutarate Kd of 20 ± 4 μM. Furthermore, l-2-hydroxyglutarate was shown to be a substrate of YgaF according to both the oxygen electrode and OPDA assays (with the latter providing a Km of 95 ± 26 μM, a Vmax of 113 ± 14 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1, and a turnover number, kcat, of 0.08 s−1). The product of the reaction of YgaF with l-2-hydroxyglutarate was expected to be α-ketoglutarate on the basis of the OPDA reactivity and the oxidase activity with this substrate. The production of α-ketoglutarate was directly confirmed by HPLC (330 μM α-ketoglutarate produced from 380 μM substrate). Although α-ketoglutarate is the product of the enzymatic reaction, the addition of this oxo acid to anaerobic YgaF (with its FAD reduced by dithionite) did not result in flavin oxidation; these results indicate that the reaction is essentially irreversible, in agreement with the high reduction potential of the flavin.

FIG. 4.

Titration of anaerobic YgaF with l-2-hydroxyglutarate. (A) Anaerobic YgaF (47 μM in 25 mM HEPES, pH 8.2, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol) was adjusted to contain 19, 38, 57, 95, 133, and 171 μM l-2-hydroxyglutarate. (B) Fractional change in absorbance at 450 nm as a function of the concentration of free substrate in the solution.

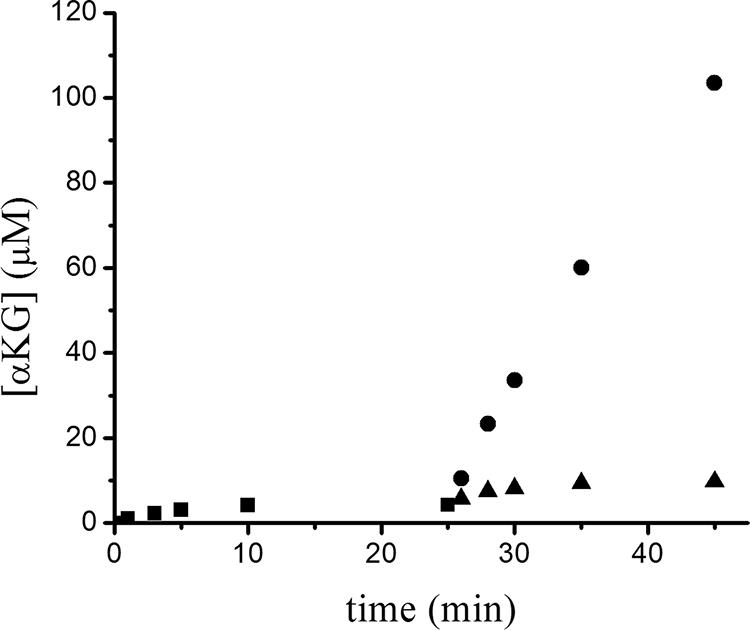

In contrast to the results obtained with l-2-hydroxyglutarate, no flavin reduction was detected with d-2-hydroxyglutarate and only very low levels of activity were detected for this compound by the OPDA procedure. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the low-level reactivity of d-2-hydroxyglutarate was transient and was repeated when another aliquot of the substrate was added; thus, we conclude that d-2-hydroxyglutarate contains a low concentration of contaminating l isomer.

FIG. 5.

Time course of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) production for the reaction of YgaF with the two enantiomers of 2-hydroxyglutarate. YgaF (1 μM) was incubated with d-2-hydroxyglutarate (300 μM) in 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol at pH 8.2 at 25°C. Aliquots of 970 μl were collected from the reaction mixture at 1, 3, 5, 10, and 25 min and treated with OPDA (square symbols). The remaining reaction mixture was separated into two equal portions. Additional d-2-hydroxyglutarate (300 μM) was added to one portion (triangle symbols), and l-2-hydroxyglutarate (300 μM) was added to the other (circles). Aliquots of 970 μl were collected from both reactions at 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, and 40 min and treated with OPDA.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that YgaF contains a noncovalently bound FAD and exhibits oxidase activity toward l-2-hydroxyglutarate. Whereas the reaction of reduced enzyme with oxygen is quite fast (an apparent second-order rate constant of >23 mM−1 s−1), the overall reaction is slow (kcat, ∼0.08 s−1) indicating slow electron transfer from the substrate to the enzyme-bound FAD. The use of l-2-hydroxyglutarate as a substrate was not surprising given the close sequence similarity (41% identity) between this E. coli protein and human l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase. Furthermore, the finding that YgaF is an oxidase rather than a dehydrogenase is consistent with the ability of the protein to generate a complex with sulfite. The sulfite Kd (102 μM) was used to approximate the reduction potential of the protein (−25 mV at pH 7). This value is close to the reduction potential measured spectroscopically when using MB and PMS as redox dyes (+19 mV at pH 7.5) and suggests that Em increases with increasing pH. The relatively high reduction potential of this flavoprotein explains the apparent irreversibility of the reaction (i.e., the inability of reduced YgaF to reduce α-ketoglutarate under anaerobic conditions) when monitored spectroscopically.

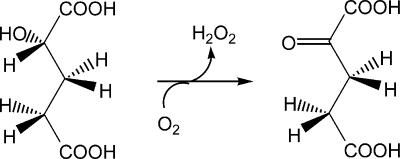

It is instructive to compare the bacterial FAD-containing YgaF to the related mammalian enzyme l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase, for which evidence also suggests an FAD dependence (27, 28). The Km of YgaF for l-2-hydroxyglutarate (95 μM) is lower than that reported for l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenases from either humans or rats (800 and 150 μM, respectively) (27). In mammalian cells, l-2-hydroxyglutarate has been suggested to arise from the nonspecific reduction of α-ketoglutarate by l-malate dehydrogenase. Thus, the physiological role of the human enzyme is proposed to be a metabolite repair enzyme to prevent accumulation of this compound in tissues (29). Mutation of the gene that encodes human l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (in particular, mutations associated with K81E and E176D variants or deletion of exon 9 [27]) leads to this accumulation, a disease state that is known as l-2-hydroxyglutarate aciduria and is characterized by ataxia, mental deficiency with subcortical leukoencephalopathy, and cerebellar atrophy (28). It is possible that l-malate dehydrogenase catalyzes similar aberrant chemistry in E. coli. SerA, which catalyzes the reversible oxidation of 3-phospho-d-glycerate to form 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate with NAD+ as a cofactor, also is known to reduce α-ketoglutarate to form both d-2-hydroxyglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate (36). In addition to the reductases that could produce l-2-hydroxyglutarate, hydroxyglutarate (of undefined enantiospecificity) has long been known to derive from the condensation of propionyl coenzyme A and glyoxylate for propionate-grown cells (25, 26, 35). We propose that E. coli uses YgaF to oxidize the metabolically generated l-2-hydroxyglutarate to recover α-ketoglutarate, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Given the role of YgaF as an l-2-hydroxylglutarate oxidase, we propose that the ygaF gene be renamed lhgO.

FIG. 6.

The reaction catalyzed by YgaF.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dave Arscott for 5-deazaflavin and Rachel Morr for assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM065384.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliverti, A., B. Curti, and M. Vanoni. 1999. Identifying and quantifying FAD and FMN in simple and in iron-sulfur-containing flavoproteins, p. 9-23. In S. K. Chapman and G. A. Reid (ed.), Flavoprotein protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Binzak, B. A., J. G. Vockley, R. B. Jenkins, and J. Vockley. 2000. Structure and analysis of the human dimethylglycine dehydrogenase gene. Mol. Genet. Metab. 69181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chance, M. R., A. R. Bresnick, S. K. Burley, J.-S. Jiang, C. D. Lima, A. Sali, S. C. Almo, J. B. Bonanno, J. A. Buglino, S. Boulton, H. Chen, N. Eswar, G. He, R. Huang, V. Ilyin, L. McMahan, U. Pieper, S. Ray, M. Vidal, and L. K. Wang. 2002. Structural genomics: a pipeline for providing structures for the biochemist. Protein Sci. 11723-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Colibus, L., and A. Mattevi. 2006. New frontiers in structural flavoenzymology. Curr. Opinion Struct. Biol. 16722-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodt, G., D. G. Kim, S. A. Reimann, B. E. Reuber, K. McCabe, S. J. Gould, and S. J. Mihalik. 2000. l-Pipecolic acid oxidase, a human enzyme essential for the degradation of l-pipecolic acid, is most similar to the monomeric sarcosine oxidases. Biochem. J. 345487-494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan-Abdallah, A., G. Zhao, and M. S. Jorns. 2006. Role of the covalent flavin linkage in monomeric sarcosine oxidase. Biochemistry 459454-9462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi, T., H. Tsuchiya, H. Todoriki, and H. Naruse. 1982. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of α-keto acids in human urine and plasma. Anal. Biochem. 122173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessières, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S.-K. Choi, J.-J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, N. J. Cummings, R. A. Daniel, F. Denizot, K. M. Devine, A. Düsterhöft, S. D. Ehrlich, P. T. Emmerson, K. D. Entian, J. Errington, C. Fabret, E. Ferrari, D. Foulger, C. Fritz, M. Fujita, Y. Fujita, S. Fuma, A. Galizzi, N. Galleron, S.-Y. Ghim, P. Glaser, A. Goffeau, E. J. Golightly, G. Grandi, G. Guiseppi, B. J. Guy, K. Haga, J. Haiech, C. R. Harwood, A. Hènaut, H. Hilbert, S. Holsappel, S. Hosono, M.-F. Hullo, M. Itaya, L. Jones, B. Joris, D. Karamata, Y. Kasahara, M. Klaerr-Blanchard, C. Klein, Y. Kobayashi, P. Koetter, G. Koningstein, S. Krogh, M. Kumano, K. Kurita, A. Lapidus, S. Lardinois, J. Lauber, V. Lazarevic, S.-M. Lee, A. Levine, H. Liu, S. Masuda, C. Mauël, C. Mèdigue, N. Medina, R. P. Mellado, M. Mizuno, D. Moesti, S. Nakai, M. Noback, D. Noone, M. O'Reilly, K. Ogawa, A. Ogiwara, B. Oudega, S.-H. Park, V. Parro, T. M. Pohl, D. Portetelle, S. Porwollik, A. M. Prescott, E. Presecan, P. Pujic, B. Purnelle, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leferink, N. G. H., D. P. H. M. Heuts, M. W. Fraaije, and W. J. H. van Berkel. 6 February 2008. The growing VAO flavoprotein family. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. doi: 10.1016/j.abb. 2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Leys, D., J. Basran, and N. S. Scutton. 2003. Channeling and formation of ‘active’ formaldehyde in dimethylglycine oxidase. EMBO J. 224038-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macheroux, P. 1999. UV-visible spectroscopy as a tool to study flavoproteins, p. 1-8. In S. K. Chapman and G. A. Reid (ed.), Flavoprotein protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Marschall, C., V. Labrousse, M. Kreimer, D. Weichart, A. Kolb, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1998. Molecular analysis of the regulation of csiD, a carbon starvation-inducible gene in Escherichia coli that is exclusively dependent on σs and requires activation by cAMP-CRP. J. Mol. Biol. 276339-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massey, V., and P. Hemmerich. 1978. Photoreduction of flavoproteins and other biological compounds catalyzed by deazaflavins. Biochemistry 179-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massey, V., F. Müller, R. Feldberg, M. Schuman, P. A. Sullivan, L. G. Howell, S. G. Mayhew, R. G. Matthews, and G. P. Foust. 1969. The reactivity of flavoproteins with sulfite. Possible relevance to the problem of oxygen reactivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2443999-4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massey, V., M. Stankovich, and P. Hemmerich. 1978. Light-mediated reduction of flavoproteins with flavins as catalysts. Biochemistry 171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metzner, M., J. Germer, and R. Hengge. 2004. Multiple stress signal integration in the regulation of the complex σl151s-dependent csiD-ygaF-gabDTP operon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 51799-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihalik, S. J., M. McGuinness, and P. A. Watkins. 1991. Purification and characterization of peroxisomal l-pipecolic acid oxidase from monkey liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2664822-4830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miroux, B., and J. E. Walker. 1996. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane protein and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 260289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller, F., and V. Massey. 1969. Flavin-sulfite complexes and their structures. J. Biol. Chem. 2444007-4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pande, S., S. K. Ghosh, S. Nath, S. Praharaj, S. Jana, S. Panigrahi, S. Basu, and T. Pal. 2006. Reduction of methylene blue by thiocyanate: kinetic and thermodynamic aspects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 299421-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollegioni, L., D. Porrini, G. Molla, and M. S. Pilone. 2000. Redox potentials and their pH dependence of d-amino-acid oxidase of Rhodotorula gracilis and Trigonopsis variabilis. Eur. J. Biochem. 2676624-6632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prince, R. C., S. J. G. Linkletter, and L. Dutton. 1981. The thermodynamic properties of some commonly used oxidation-reduction mediators, inhibitors, and dyes, as determined by polarography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 635132-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeves, H. C., and S. J. Ajl. 1962. Alpha-hydroxyglutaric acid synthetase. J. Bacteriol. 84186-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reeves, H. C., W. J. Stahl, and S. J. Ajl. 1963. α-Hydroxyglutarate: product of an enzymatic beta-condensation between glyoxylate and propionyl-coenzyme A. J. Bacteriol. 861352-1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rzem, R., E. Van Schaftingen, and M. Veiga-da-Cunha. 2006. The gene mutated in l-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria encodes l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase. Biochimie 88113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rzem, R., M. Veiga-da-Cunha, G. Noël, S. Goffette, M.-C. Nassogne, B. Tabarki, C. Schöller, T. Marquardt, M. Vikkula, and E. Van Schaftingen. 2004. A gene encoding a putative FAD-dependent l-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase is mutated in l-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10116849-16854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rzem, R., M.-F. Vincent, E. Van Schaftingen, and M. Veiga-da-Cunha. 2007. l-2-Hydroxyglutaric aciduria, a defect of metabolite repair. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30681-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider, B. L., S. Ruback, A. K. Kiupakis, H. Kasbarian, C. Pybus, and L. Reitzer. 2002. The Escherichia coli gabDTPC operon: specific γ-aminobutyrate catabolism and nonspecific induction. J. Bacteriol. 1846976-6986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sefler, A. M., M. C. Kozlowski, T. Guo, and P. A. Bartlett. 1997. Design, synthesis, and evolution of a depsipeptide mimic of tendamistat. J. Org. Chem. 6293-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki, K., H. Sagai, S. Imamura, and M. Sugiyama. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, overexpression in Escherichia coli of a sarcosine oxidase-encoding gene linked to the Bacillus creatinase gene. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 77231-234. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzergerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelley, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weidman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Borodovsky, P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter. 1997. The complete genome of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh, C. T. 1979. Enzymatic reaction mechanisms. W. H. Freeman & Company, San Francisco, CA.

- 35.Wegener, W. S., H. C. Reeves, R. Rabin, and S. J. Ajl. 1968. Alternate pathways of metabolism of short-chain fatty acids. Bacteriol. Rev. 321-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, G., and M. E. Winkler. 1996. A novel α-ketoglutarate reductase activity of the serA-encoded 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli K-12 and its possible implications for human 2-hydroxylglutaric aciduria. J. Bacteriol. 178232-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]