Abstract

Some members of Burkholderiales are able to grow on methanol but lack the genes (mxaFI) responsible for the well-characterized two-subunit pyrroloquinoline quinone-dependent quinoprotein methanol dehydrogenase that is widespread in methylotrophic Proteobacteria. Here, we characterized novel, mono-subunit enzymes responsible for methanol oxidation in four strains, Methyloversatilis universalis FAM5, Methylibium petroleiphilum PM1, and unclassified Burkholderiales strains RZ18-153 and FAM1. The enzyme from M. universalis FAM5 was partially purified and subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of fight peptide mass fingerprinting. The resulting peptide spectrum was used to identify a gene candidate in the genome of M. petroleiphilum PM1 (mdh2) predicted to encode a type I alcohol dehydrogenase related to the characterized methanol dehydrogenase large subunits but at less than 35% amino acid identity. Homologs of mdh2 were amplified from M. universalis FAM5 and strains RZ18-153 and FAM1, and mutants lacking mdh2 were generated in three of the organisms. These mutants lost their ability to grow on methanol and ethanol, demonstrating that mdh2 is responsible for oxidation of both substrates. Our findings have implications for environmental detection of methylotrophy and indicate that this ability is widespread beyond populations possessing mxaF, the gene traditionally used as a genetic marker for environmental detection of methanol-oxidizing capability. Our findings also have implications for understanding the evolution of methanol oxidation, suggesting a convergence toward the enzymatic function for methanol oxidation in MxaF and Mdh2-type proteins.

Methanol dehydrogenase (MDH) is a key enzyme in utilization of methane and methanol by methylotrophic proteobacteria (1, 2). This is a pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-dependent quinoprotein that acts in the periplasm. Like other quinoproteins, MDH is assayed in vitro in a dye-linked system using artificial electron acceptors such as phenazine methosulphate and dichlorophenolindophenol. It is typically measured at high pH (9-11) in the presence of ammonia as an essential activator (1-3). MDH oxidizes a wide range of primary alcohols but has especially high affinity for methanol (Km value of about 20 μM). MDH and its prosthetic group were first described more than 40 years ago, making it one of the most thoroughly studied quinoprotein dehydrogenases (9, 12, 32, 44, 46). Gene clusters encoding the structural subunits of MDH (mxaFI), the specific electron acceptor cytochrome cL (mxaG), and a number of accessory proteins (mxaJRSACKLD) have been found well conserved in a variety of methylotroph genomes (5, 6, 25, 42), and the gene encoding the large subunit, mxaF, has been used as a marker for methylotrophy in environmental studies (27, 28). However, a few methylotrophic isolates have been described that appear to lack mxa genes. In some cases this is evidenced by the analysis of complete genomes (10, 20) and in others by the inability to PCR amplify the mxaF gene (18, 37) or detect the protein via Western blot hybridization (31). Dye-linked quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenases have been implicated in enabling methylotrophy in strains lacking mxaFI (33). However, the identity of the gene(s) involved has not been revealed.

Burkholderiales have recently emerged as an order within Betaproteobacteria containing methylotrophic representatives. These so far belong to two new genera, Methylibium (20, 29) and Methyloversatilis (18). Phenotypically and metabolically methylotrophic Burkholderiales differ from the well-characterized betaproteobacterial methylotrophs of the family Methylophilaceae (1, 24) by being able to grow on a variety of multicarbon compounds in addition to C1 compounds (methanol, methylamine, and formaldehyde but not methane) and employing the serine cycle for formaldehyde assimilation instead of the ribulose monophosphate cycle (18, 20). These organisms have also been shown to lack the traditional MDH encoded by mxaFI, suggesting that they use an alternative enzyme (18, 20). Knowledge about this enzyme and the respective genes would be important for accurate estimates of numbers of potentially methylotrophic Burkholderiales in the environment. In addition, revealing the identity of the genes encoding alternative MDH enzymes would contribute to a better understanding of the evolution of methylotrophy as a metabolic capability. In this work, we explored properties of MDH enzymes in methylotrophic Burkholderiales, identified the respective genes, and confirmed their role in methylotrophy via mutation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and phylotyping of two novel methylotrophic Burkholderiales.

Strain RZ18-153 was isolated from Lake Washington sediment from an enrichment supplemented by 5 mM formaldehyde (made up of a 37% formaldehyde stock solution stabilized with 10 to 15% methanol; Fisher Scientific), essentially as previously described for Methyloversatilis universalis FAM5 (18). Strain FAM1 was isolated via a dilution-to-extinction technique essentially as previously described for M. universalis 500 (18) except that 1 mM formaldehyde made up by autoclaving paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a substrate. Both strains were found to be able to grow on methanol as a single carbon and energy source (data not shown). 16S rRNA genes were PCR amplified and sequenced as described before (18), revealing that both strains belonged to Burkholderiales and were closely related to M. universalis FAM5 (94 and 96% similarity, respectively).

Strains and growth condition.

M. universalis FAM5 (18), Methylibium petroleiphilum PM1 (28) and strains RZ18-153 and FAM1 were grown in 0.3× Hypho medium (15) supplemented with 2 ml/liter of filter-sterilized vitamin stock solution containing the following (mg/ml): 0.25 vitamin B12, 0.05 thiamine, 0.025 folic acid, 0.075 ascorbic acid, 0.05 riboflavin, 0.05 niacin, and 0.05 vitamin B5. Methanol (60 mM), methylamine (70 mM), ethanol (40 mM), or succinate (90 mM) was used as a growth substrate. Nutrient agar or triple soy agar (BD) was used for matings. Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and Xanthobacter autotrophicus H4-14 were grown in Hypho medium (15) in the presence of 125 mM methanol. Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen), JM109, and S17-1 were grown on Luria-Bertani medium (BD). Filter-sterilized antibiotics were added as follows: 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 100 μg/ml kanamycin, and tetracycline at 0.5 μg/ml for the methylotrophic strains and 10 μg/ml for E. coli strains.

MDH assay.

Methanol-grown cells (optical density at 600 nm of 0.7 to 0.9) were harvested by centrifugation at 4,500 × g using the Sorvall RC-5B centrifuge at 4°C for 25 min. Cells were resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and passed two times through a French pressure cell at 1.2 × 108 Pa. Centrifugation was performed at 21,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. MDH activity was measured using a modification of the method of Anthony and Zatman (3) based on following the phenazine methosulfate-mediated reduction of DCPIP (2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol). The modification included the addition of CaCl2 (10 mM) to the reaction mixture for protein stabilization/activation (41), increasing the molarity of the buffer system (0.3 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8), and decreasing the concentration of methanol to 2.5 mM. The reaction was initiated by the addition of essential activator NH4Cl (45 mM). Assays were performed routinely at room temperature in plastic 1.5-ml cuvettes (Bio-Rad) in a total volume of 1 ml. DCPIP reduction was monitored spectrophotometrically at 600 nm. For the calculations, a ɛ600 absorbance coefficient of 21.9 mM−1 cm−1 was used (4).

Partial enzyme purification and enzyme kinetics.

Enzymes from M. universalis FAM5, M. petroleiphilum PM1, and strain RZ18-153 were partially purified as follows. Crude cell extracts obtained as above were treated with (NH4)2SO4 (75% saturation; supplied as powder) for 30 min at 4°C with stirring, followed by centrifugation at 4,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. To the resultant supernatants, (NH4)2SO4 was then added to 85% saturation, and samples were treated as above. The precipitated proteins were resuspended in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.5 M NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol buffer and desalted and concentrated in 25 mM HEPES buffer using Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore). The following alcohols were tested as substrates: methanol, ethanol, 1-propanol, and 1-butanol. Km values were deduced from double reciprocal plots of the initial reaction rates versus concentrations of the alcohols.

Isoelectrofocusing and in-gel activity staining.

Crude extracts were isoelectrofocused in a pH range of 3 to 9 using a PhastSystem instrument, as described by the manufacturer (Pharmacia Biotech). The running conditions were programmed as advised by the manufacturer. A total of 45 to 60 μg of protein was loaded per well. Gels were neutralized in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, for 10 min at room temperature. In-gel activity staining was performed as described by Chistoserdova and Lidstrom (7). Gels were incubated for 40 min at 35°C in the dark for activity bands to develop.

Protein purification and mass spectrometric analysis.

Crude extracts of methanol-grown cells of M. universalis FAM5 and M. petroleiphilum PM1 (optical density at 600 nm of 0.7 to 0.9; prepared as above) were subjected to preparative protein separation in 1% agarose gel prepared in 1× Tris-glycine buffer (23). In-gel activity staining was performed as above. Activity-positive bands were excised from gels and subjected to denaturing (12% sodium dodecyl sulfate) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described previously (23). Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 (Amersham Biosciences). The major polypeptide band of M. universalis FAM5 with a molecular mass of approximately 65 kDa was excised from the gel and submitted to Alphalyse (http://www.alphalyse.com/) for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of fight (MALDI-TOF) peptide mass fingerprinting after trypsin digestion. The Mascot (version 1.9.03) search program was used to match the MALDI-TOF mass spectrum against the 11 PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases predicted from the genome sequence of M. petroleiphilum PM1 (20). We verified these predictions by carrying out BLAST analyses using known PQQ-dependent quinoprotein dehydrogenase sequences (MDH, type I and type II alcohol dehydrogenase [ADH], glucose dehydrogenase, etc.) (see Fig. 3). A BLAST search with each query produced the same 11 protein candidates (Table 1).

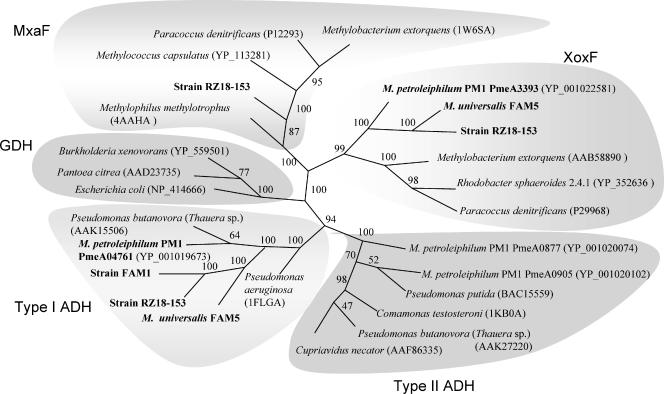

FIG. 3.

Consensus parsimony phylogenetic tree of quinoprotein ADHs. Numbers correspond to bootstrap values for 1,000 analyses (parsimony). GenBank protein accession numbers are shown. Proteins investigated in this study are shown in bold. GDH, glucose dehydrogenase.

TABLE 1.

Sequence comparisons between putative quinoproteins encoded in the genome of M. petroleiphilum PM1 and representatives of MDHs, type I ADHs, and enzymes of unknown function (XoxF)

| Polypeptide identifier | % Amino acid sequence identitya

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. methylotrophus MxaF | P. butanovora BDH | P. aeruginosa ADH | P. denitrificans XoxF | |

| MpeA0341 | 33 | 34 | 37 | 34 |

| MpeA0363 | 32 | 33 | 35 | 33 |

| MpeA0473 | 34 | 50 | 54 | 33 |

| MpeA0476 | 32 | 80 | 69 | 34 |

| MpeA0877 | 33 | 36 | 37 | 35 |

| MpeA0905 | 30 | 32 | 34 | 30 |

| MpeA1591 | 30 | 35 | 38 | 36 |

| MpeA1594 | 24 | 22 | 22 | 23 |

| MpeA1595 | 31 | 33 | 33 | 32 |

| MpeA3393 | 49 | 34 | 35 | 66 |

| MpeA3660 | 32 | 30 | 32 | 31 |

Sequences of MxaF from M. methylotrophus (46), butanol dehydrogenase from P. butanovora (40), ethanol dehydrogenase from P. aeruginosa (21), and XoxF of P. denitrificans (34) were used as queries against the genome of M. petroleiphilum PM1 (20). Matches producing identity scores above 60% are highlighted in boldface. Sequence accession numbers are as shown in Fig. 3.

DNA manipulations.

DNA was isolated using a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen). Plasmid DNA was purified using a GeneJet plasmid miniprep kit (Fermentas). E. coli transformation, restriction enzyme digestion, and ligation reactions were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (36). PCR amplification reactions were performed using Taq polymerase (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR amplification and primer design.

Partial mxaF and xoxF fragments (0.56 kb) were amplified using previously described primer sets (27, 38). Degenerate primers for PCR amplification of nearly complete (1.6 kb) mdh2 genes (PQQDH-215F, 5′-CAGCGCTACAGCCCGCTCAAG; PQQDH-1805R, 5′-GTACTGCTCGCCGTCCTGCTCCC) were designed based on alignments of DNA sequences encoding ADHs from M. petroleophilum PM1 (MpeA0476) (20), Pseudomonas butanovora (41) (NCBI accession number AF326086), Azoarcus sp. BH72 (22) (NCBI accession number NC_008702.1, gene ID 4607717), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (21) (NZ_AAKW01000014.1, locus tag Paer2_01001089). Vector NTI Advance 10 AlignX software (Invitrogen) was used for alignment. Degenerate primers for PCR amplification of nearly complete (1.3 kb) xoxF genes (XoxF-f, 5′-CGGCGTGCTGCGCGGCCACG; XoxF-r, 5′-GCCCAGCCGCCRATRCCCGAG) were designed in a similar fashion based on the alignment of homologous gene sequences from M. petroleiphilum PM1 (MpeA3393), Methylobacillus flagellatus KT (Mfla2314) (6), Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 (NCBI accession number U72662) (7), and Paracoccus denitrificans (NCBI accession number U34346) (33). Homologous primers for PCR amplification of nearly complete (1.6 kb) mxaF from RZ18-530 (RZ18-236F, 5′-CCTGACCCAGATCAACCG, and mxaF-RZ18-1850R, 5′-CATCATGCCGCCACCCATC) were designed after aligning mxaF sequences of M. flagellatus (Mfla2044) (6) and Verminephrobacter eiseniae EF01-2 (NCBI accession CP00542). PCR amplification reactions were performed using Taq polymerase (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting PCR products were purified, cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), and sequenced as previously described (18). After verification of the nucleotide sequences of the inserts, the respective plasmids were used as templates for amplification of the corresponding 5′ and 3′ gene fragments for subsequent cloning into the allelic exchange vector pCM184 (26) in order to create deletion/insertion mutant constructs, essentially as described previously (26). The resulting plasmids were transformed into E. coli S17-1, and strains harboring appropriate plasmids were used as donors in biparental matings. The kanamycin-resistant recombinants were selected on succinate plates and checked for resistance to tetracycline. Tetracycline-sensitive recombinants were chosen as potential double-crossover recombinants. The identity of the double-crossover mutants was further verified by diagnostic PCR tests using PCR primers specific to the insertion sites.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Amino acid sequences of complete or nearly complete proteins were aligned using the CLUSTAL W program (39). For phylogenetic analyses, the PHYLIP package (12) was used. Maximum likelihood, distance, and parsimony methods were employed; 1,000 bootstrap analyses were performed. Tree-branching patterns were similar for the three analyses.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank under the following accession numbers (in respective order): EU548062 and EU548068 for the mdh2 and xoxF gene fragments from M. universalis FAM5; EU548066, EU548065, and EU548067 for the mdh2, xoxF, and mxaF gene fragments from strain RZ18-153; and EU548063 for the mdh2 gene fragment from strain FAM1.

RESULTS

MDH activity in methylotrophic Burkholderiales.

MDH activity was tested in four strains of methylotrophic Burkholderiales. These included M. petroleiphilum PM1, which lacks in its genome the typical MDH gene cluster previously characterized in model alpha-, beta-, and gammaproteobacterial methylotrophs (20); M. universalis FAM5, which is negative for MDH activity as measured in standard assay conditions and for the presence of mxaF as judged by PCR amplification-based tests (18); and two other recently isolated representatives of Burkholderiales referred to here as strains RZ18-153 and FAM1. While closely related to M. universalis, these strains were positive for PCR amplification of mxaF using standard PCR primers (data not shown). Sequencing of the mxaF gene fragment from strain RZ18-153 revealed close relatedness to the sequence present in the genome of V. eiseniae EF01-2 (86% identity at the DNA level), another member of Burkholderiales (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/finished_microbes/verei/verei.home.html).

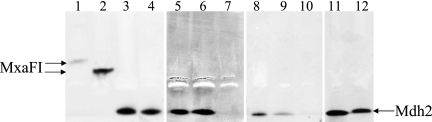

As we previously encountered difficulties measuring MDH activity in M. universalis, we performed plus-minus qualitative tests on crude extracts from cells grown on methanol, ethanol, methylamine, and succinate by activity staining after isoelectrofocusing in native polyacrylamide gels. Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 (5), and X. autotrophicus H4-14 (43), methanol utilizers possessing the classical MDH, were used as controls. We observed positive activity bands for all the strains grown on methanol or ethanol. Activity bands were faint or absent in extracts of cells grown on methylamine or succinate (Fig. 1 and data not shown), suggesting that the enzyme responsible for activity staining was inducible by both methanol and ethanol. The position in gels of the activity bands corresponding to the Burkholderiales MDH enzymes was distinctly different from the positions of the bands corresponding to MDH enzymes from Methylobacterium extorquens and X. autotrophicus, suggesting a significantly more basic pI for these “novel” enzymes.

FIG. 1.

In-gel activity staining of MDH after isoelectrofocusing in polyacrylamide gels (Pharmacia Biotech). A total of 45 to 60 mg of protein was loaded per lane. Running conditions were as recommended by the manufacturer (Pharmacia Biotech). Gels were neutralized in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, and stained as described previously (7) for 40 min at 35°C in the dark. Arrows show bands corresponding to MxaFI and Mdh2. Lane 1, M. extorquens AM1 grown on methanol; lane 2, X. autotrophicus H4-14 grown on methanol; lanes 3 to 5, M. petroleiphilum PM1 grown, respectively, on methanol and ethanol and grown on succinate and then induced with methanol as described previously (7); lane 6, mutant of M. petroleiphilum PM1 defective in xoxF grown on succinate and induced with methanol; lane 7, mutant of M. petroleiphilum PM1 defective in mdh2 grown on succinate and induced with methanol; lanes 8 to 10, M. universalis FAM5 grown, respectively, on methanol, methylamine, and succinate; lanes 11 and 12, strains FAM1 and RZ18-153, respectively, grown on methanol.

We obtained further indication of the novel nature of Burkholderiales MDH enzymes by testing for optimal MDH assay conditions. The enzymes in question were shown to be more labile than MDH enzymes encoded by mxaFI (8), losing all of their activity in cells that were frozen and thawed. They required a high-molarity buffer system (0.3 M Tris-HCl) for maximum activity (approximately fivefold higher than at 0.1 M Tris-HCl) and lower methanol concentration than the standard protocol (3) (see Materials and Methods), and they had a slightly more acidic pH optimum than known MDH enzymes (pH 8.5 versus pH 9 to 11). However, like MDH as well as type I ADH enzymes, the novel enzymes required ammonia for activation. Using the optimized assay, we measured MDH activity in cell extracts of all the Burkholderiales strains involved in this study and obtained activities from 0.10 ± 0.03 to 0.15 ± 0.05 μmol/min/mg of protein (from three biological replicates) (Table 2). Km values were determined for partially purified enzymes from M. universalis FAM5, M. petroleiphilum PM1, and strain RZ18-153l and compared to the parameters previously observed for a typical mxaFI-encoded MDH (from Methylophilus methylotrophus) and a typical ethanol dehydrogenase (from P. aeruginosa) (Table 2). Strain FAM1, due to its close relatedness to strain RZ18-153, was excluded from these analyses. The enzymes from M. universalis FAM5 and strain RZ18-153 revealed kinetic properties very similar to each other and to those of the classic MDH from M. methylotrophus, having the highest affinity toward methanol and exhibiting the highest reaction velocity with methanol. The enzyme from M. petroleiphilum PM1 revealed a much lower affinity for methanol than the enzymes from M. universalis FAM5 and strain RZ18-153, but this affinity was more than two orders of magnitude higher than the affinity of a typical ethanol dehydrogenase (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reaction velocity and substrate affinity of enzymes partially purified in this work compared to typical methanol and ethanol dehydrogenases

| Substrate | Kinetics of the indicated straina

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M. universalis FAM5

|

Strain RZ18-153

|

M. petroleiphilum PM1

|

M. methylotrophus W3A1

|

P. aeruginosa

|

||||||

| Km (mM) | % of Vmax | Km (mM) | % of Vmax | Km (mM) | % of Vmax | Km (mM) | % of Vmax | Km (mM) | % of Vmax | |

| Methanol | 0.01 | 100 (0.59) | 0.02 | 100 (0.43) | 0.29 | 100 (0.23) | 0.02 | 100 (6.45) | 94 | 100 (5.63) |

| Ethanol | 0.05 | 93 | 0.04 | 93 | 0.10 | 109 | 0.03 | 76 | 0.01 | 160 |

| 1-Propanol | 0.50 | 22 | 0.19 | 47 | 0.09 | 111 | 0.28 | 94 | 0.02 | 222 |

| 1-Butanol | 0.50 | 21 | 0.20 | 47 | 0.10 | 100 | 0.29 | 89 | ND | 104 |

Data for a classic MDH (from M. methylotrophus [12]) and a classic ethanol dehydrogenase (from P. aeruginosa [13]) were used for comparisons. Purity of the enzymes investigated in this work was estimated based on scanning the images of gels after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using Geliance GeneTools software (Perkin-Elmer). Enzyme purity was estimated at 32, 38, and 46% for M. universalis FAM5, strain RZ18-153, and M. petroleiphilum PM1, respectively. Values in parentheses represent Vmax in U/mg of protein. ND, not determined.

Protein identification.

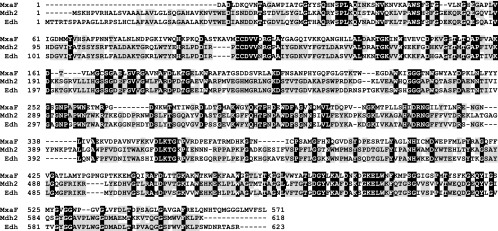

To obtain further insights into the identity of the enzyme responsible for MDH activity in Burkholderiales strains, we performed preparative native agarose gel electrophoresis using crude cell extracts of M. universalis FAM5 and M. petroleiphilum PM1. The activity bands were excised from gels and subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. In each case, one major polypeptide band was observed with a molecular mass of approximately 65 kDa, and no light band corresponding to a typical MxaI was detected (data not shown). The M. universalis FAM5 band was excised from the gel and submitted to Alphalyse for MALDI-TOF peptide mass fingerprinting. The resulting MALDI-TOF spectra were screened against an in-house protein database created of 11 predicted quinoprotein dehydrogenases translated from the genome of M. petroleiphilum PM1 (Table 1). Of the 11 polypeptides tested, only one was positively matched with the MALDI-TOF spectrum: MpeA0476 (YP_001019673; two polypeptide matches; 3% coverage). Based on its primary sequence, this polypeptide is closely related to type I periplasmic quinoprotein ADHs (up to 80% amino acid identity), a number of which have been purified and characterized (13, 40). The same polypeptide has been previously implicated in having a role as a major ethanol dehydrogenase in this organism, based on its up-regulation during growth on ethanol as judged by transcriptional microarray analysis (17). Type I quinoprotein ADHs typically exhibit broad substrate specificity toward various primary, secondary, and aromatic alcohols but reveal very poor affinity for methanol (13, 40). MpeA0476 shared less than 35% identity with MxaF polypeptides of known methylotrophs. Alignment of the sequence of MpeA0476 with the sequences of MxaF and a typical type I quinoprotein ADH is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the sequence of Mdh2 from M. petroleiphilum with the sequences of MxaF from M. methylotrophus and type I ADH (Edh) from P. aeruginosa. Amino acid residues conserved in all three proteins are shaded in black, and residues conserved in two out of three proteins are shaded in gray. Accession numbers are as shown in Fig. 3.

The predicted polypeptide most closely related to MxaF was MpeA3393 (approximately 50% amino acid identity). However, this polypeptide was even more closely related to XoxF polypeptides found in a variety of proteobacterial species including both methylotrophs and nonmethylotrophs (6, 7, 16, 38, 45). xoxF genes have been previously mutated in two methylotrophs, M. extorquens and Paracoccus denitrificans, without resulting in any visible effect on methanol-oxidizing capability (7, 16). However, more recently a function was suggested for XoxF in photosynthesis-dependent methanol utilization by Rhodobacter sphaeroides based on mutant phenotypes (45).

To test whether predicted proteins similar to MpeA0476 were encoded in other Burkholderiales methylotrophs, we designed primers for PCR amplification, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Gene fragments were amplified from M. universalis FAM5 and strains RZ18-153 and FAM1, followed by sequencing. These gene fragments were highly similar to each other (90 to 96% identical at the DNA level) and to the gene encoding MpeA0476 (84% identical). Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated that predicted polypeptide sequences translated from these genes clustered together with type I ADH sequences and formed a branch clearly separated from the branch containing the MxaF predicted polypeptides (Fig. 3).

Mutant generation and phenotypic characterization.

In order to confirm the involvement of MpeA0476-like genes (tentatively named mdh2) in methanol oxidation in methylotrophic Burkholderiales, these genes were inactivated in M. petroleiphilum PM1, M. universalis FAM5, and strain RZ18-153 using a previously described insertion/deletion mutagenesis technique (26). We also constructed mutants of M. petroleiphilum PM1 and M. universalis FAM5 lacking functional xoxF homologs. While the only MDH activity band in strain RZ18-153 corresponded to Mdh2, the organism was positive for the presence of an mxaF gene homolog; so we mutated this gene as well and investigated the phenotypes of all the mutants. All of the mutants lacking functional mdh2 have lost the ability to grow on both methanol and ethanol, and they were also negative for MDH activity (Fig. 1 and data not shown). However, the mutation of the mxaF gene homolog had no effect on methylotrophic growth of the strain RZ18-153. Mutants of M. universalis FAM1 and M. petroleiphilum PM1 with lesions in xoxF homologs as well as the mutant of strain RZ18-153 with a lesion in the mxaF gene homolog retained wild-type growth characteristics and remained positive for in-gel MDH activity staining. These results strongly point toward Mdh2 as the major methanol oxidation enzyme in methylotrophic Burkholderiales.

DISCUSSION

Until recently, the ability to oxidize methanol by gram-negative bacteria has been attributed almost exclusively to the MDH enzyme encoded by mxaFI (14, 24). The mxa genes are well conserved among different classes of proteobacteria (alpha, beta, and gamma) in terms of both gene clustering and protein sequence identity (5, 6, 25, 42), suggesting a monophyletic origin for the mxa (mox)-encoded methanol oxidation machinery. Based on its conservation, mxaF has served as a genetic marker for environmental detection of methylotrophy (27, 28). However, recent studies involving discovery and analysis of novel methylotrophs, both within and outside of Proteobacteria, demonstrated the lack of mxaFI gene homologs (10, 18, 31, 37), implicating the existence of alternative enzymes responsible for methanol oxidation. In this work, we investigated the nature of methanol-oxidizing enzymes in methylotrophs belonging to the order of Burkholderiales. Methylotrophs of this group have already been shown to rely on noncanonical biochemical schemes for methylotrophy as they are the first examples of betaproteobacterial methylotrophs to employ the serine cycle instead of the traditional ribulose monophosphate cycle for formaldehyde assimilation (18, 20). Based on the experiments presented here, these organisms also employ a noncanonical MDH for methanol oxidation, named here Mdh2. In terms of the primary sequence as well as subunit composition, Mdh2 enzymes are more similar to type I ADHs that typically exhibit low affinity for methanol than to the mxaFI-encoded MDH enzymes (13, 40). Akin to traditional MDH enzymes, Mdh2 appears to be responsible for the oxidation of both methanol and ethanol. While a function in methanol oxidation has been recently suggested for the ubiquitous Xox system (45), analyses presented here demonstrate that in Burkholderiales, as in the previously tested nonphotosynthetic alphaproteobacterial methylotrophs (7, 16), a function for xoxF in methylotrophy could not be demonstrated.

The discovery of the novel MDH has major implications for (i) understanding the evolution of enzymes and pathways that enable methylotrophy and (ii) environmental detection of methanol-oxidizing capabilities. Previous analyses of methylotrophy pathways in betaproteobacterial methylotrophs suggested that representatives of Methylophilales and Burkholderiales must have acquired genes and pathways enabling methylotrophy independently, based on pathway distribution in these organisms and phylogeny of the proteins involved in the shared pathways (6, 19). This work demonstrated that enzymes enabling methanol oxidation are also different in Methylophilales and Burkholderiales. The novel MDH enzymes characterized here are closely related to ADHs typically exhibiting very low affinity for methanol. The most likely evolutionary scenario to explain the emergence of Mdh2 would be a single or a few point mutations in the catalytic center of a type I ADH, resulting in increased affinity for methanol rather than divergence from MxaF under selective pressure. The existence of such selective pressure is also unlikely, as Methylophilales and Burkholderiales methylotrophs coinhabit the same ecological niches (18, 30). Thus, methanol affinity exhibited by MxaFI and Mdh2 appears to be a result of convergent evolution.

The discovery of the novel MDH enabling methylotrophy in Burkholderiales has major implications for detection of the methanol-oxidizing capability in natural microbial populations. To date, the methylotrophic Burkholderiales have been overlooked by molecular approaches as the mxaF-directed probes and primers would not detect them. However, it appears that in some environments, Mdh2 may be the dominant methanol oxidation system. For example, a number of mdh2-like sequences are present in the metagenome resulting from global ocean sampling (35) while no sequences closely related to mxaF sequences are present. Conversely, analysis of mxaF gene fragments amplified from some environments may overestimate the methylotrophic capability as some of the mxaF genes, as we demonstrated here by the examples of strains RZ18-153 and FAM1, do not appear to code for functional MDH, likely due to lack of expression. Thus, detection of mxaF in environmental samples can no longer be considered sufficient to imply that methylotrophic growth occurs.

In conclusion, this study expands our understanding of the pathways enabling methylotrophy in proteobacteria by identifying a novel MDH, named Mdh2, which may be at least as widespread in natural bacterial communities as the well-studied mxaFI-encoded MDH, and suggests that the methanol-oxidizing capabilities of Burkholderiales and Methylophilales evolved independently. Our findings should have a major impact on environmental detection of methylotrophs, highlighting the role of Burkholderiales in global cycling of single-carbon compounds.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. Munk (Alphalyse) for help with protein identification.

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation as part of the Microbial Observatories Program (MCB-0131957). Partial support for K.R.H. was provided by a grant (5 P42 ES004699) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, C. 1982. The biochemistry of methylotrophs. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 2.Anthony, C. 2004. The quinoprotein dehydrogenases for methanol and glucose. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 4282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony, C., and L. J. Zatman. 1967. The microbial oxidation of methanol. The prosthetic group of the alcohol dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas sp. 27: a new oxidoreductase prosthetic group. Biochem. J. 104960-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong, J. M. 1964. The molar extinction coefficient of 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 86194-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chistoserdova, L., S. W. Chen, A. Lapidus, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. Methylotrophy in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 from a genomic point of view. J. Bacteriol. 1852980-2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chistoserdova, L., A. Lapidus, C. Han, L. Goodwin, L. Saunders, T. Brettin, R. Tapia, P. Gilna, S. Lucas, P. M. Richardson, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2007. The genome of Methylobacillus flagellatus, the molecular basis for obligate methylotrophy, and the polyphyletic origin of methylotrophy. J. Bacteriol. 1894020-4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chistoserdova, L., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1997. Molecular and mutational analysis of a DNA region separating two methylotrophy gene clusters in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Microbiology 1431729-1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson, V. L., J. Wu, B. Miller, and L. H. Jones. 1992. Factors affecting the stability of methanol dehydrogenase from Paracoccus denitrificans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 7353-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duine, J. A., J. Frank, and J. Westerling. 1978. Purification and properties of methanol dehydrogenase from Hyphomicrobium X. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 524277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunfield, P. F., A. Yuryev, P. Senin, A. V. Smirnova, M. B. Stott, S. Hou, B. Ly, J. H. Saw, Z. Zhou, Y. Ren, J. Wang, B. W. Mountain, M. A. Crowe, T. M. Weatherby, P. L. Bodelier, W. Liesack, L. Feng, L. Wang, and M. Alam. 2007. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 450879-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenstein, J. 2003. Inferring phylogenies. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- 12.Ghosh, R., and J. R. Quayle. 1981. Purification and properties of the methanol dehydrogenase from Methylophilis methylotrophus. Biochem. J. 199245-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Görisch, H., and M. Rupp. 1989. Quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 5635-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson, R. S., and T. E. Hanson. 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60439-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harder, W., M. Attwood, and J. R. Quayle. 1973. Methanol assimilation by Hyphomicrobium spp. J. Gen. Microbiol. 78155-163. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harms, N., J. Ras, S. Koning, W. N. M. Reijnders, A. H. Stouthamer, and R. G. M. van Spanning. 1996. Genetics of C1 metabolism regulation in Paracoccus denitrificans, p. 126-132. In M. E. Lidstrom and F. R. Tabita (ed.), Microbial growth on C1 compounds. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 17.Hristova, K. R., R. Schmidt, A. Y. Chakicherla, T. C. Legler, J. Wu, P. S. Chain, K. M. Scow, and S. R. Kane. 2007. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Methylibium petroleiphilum PM1 exposed to the fuel oxygenates methyl tert-butyl ether and ethanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 737347-7357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., P. De Marco, S. Bowerman, C. C. Pacheco, J. C. Lara, M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Chistoserdova. 2006. Methyloversatilis universalis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel taxon within the Betaproteobacteria represented by three methylotrophic isolates. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 562517-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., N. Korotkova, G. Crowther, C. J. Marx, M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Chistoserdova. 2005. Analysis of gene islands involved in methanopterin-linked C1 transfer reactions reveals new functions and provides evolutionary insights. J. Bacteriol. 1874607-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kane, S. R., A. Y. Chakicherla, P. S. Chain, R. Schmidt, M. W. Shin, T. C. Legler, K. M. Scow, F. W. Larimer, S. M. Lucas, P. M. Richardson, and K. R. Hristova. 2007. Whole-genome analysis of methyl tert-butyl ether-degrading beta-proteobacterium Methylibium petroleiphilum PM1. J. Bacteriol. 1891931-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keitel, T., A. Diehl, T. Knaute, J. J. Stezowski, W. Hohne, and H. Görisch. 2000. X-ray structure of the quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: basis of substrate specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 297961-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause, A., A. Ramakumar, D. Bartels, F. Battistoni, T. Bekel, J. Boch, M. Bohm, F. Friedrich, T. Hurek, L. Kraus., B. Linke, A. C. McHardy, A. Sarkar, S. Schneiker, A. A. Syed, R. Thauer, F. J. Vorholter, S. Weidner, A. Puhler, B. Reinhold-Hurek, O. Kaiser, and A. Goesmann. 2006. Complete genome of the mutualistic, N2-fixing grass endophyte Azoarcus sp. strain BH72. Nat. Biotechnol. 241385-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lidstrom, M. E. 2001. Aerobic methylotrophic prokaryotes, p. 223-244. In E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY.

- 25.Lidstrom, M. E., C. Anthony, F. Biville, F. Gasser, P. Goodwin, R. S. Hanson, and N. Harms. 1994. New unified nomenclature for genes involved in the oxidation of methanol in gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 117103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marx, C. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2002. Broad-host-range cre-lox system for antibiotic marker recycling in gram-negative bacteria. BioTechniques 331062-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald, I. R., and J. C. Murrell. 1997. The methanol dehydrogenase structural gene mxaF and its use as a functional gene probe for methanotrophs and methylotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 633218-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald, I. R., L. Bodrossy, Y. Chen, and J. C. Murrell. 2008. Molecular ecology techniques for the study of aerobic methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 741305-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakatsu, C. H., K. Hristova, S. Hanada, X. Y. Meng, J. R. Hanson, K. M. Scow, and Y. Kamagata. 2006. Methylibium petroleiphilum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel methyl tert-butyl ether-degrading methylotroph of the Betaproteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56983-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nercessian, O., E. Noyes, M. G. Kalyuzhnaya, M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Chistoserdova. 2005. Bacterial populations active in metabolism of C1 compounds in the sediment of Lake Washington, a freshwater lake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 716885-6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pacheco, C. C., J. F. Passos, P. Moradas-Ferreira, and P. De Marco. 2003. Strain PM2, a novel methylotrophic fluorescent Pseudomonas sp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 227279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker, M. W., A. Cornish, V. Gossain, and D. J. Best. 1987. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction characterization of methanol dehydrogenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Eur. J. Biochem. 164223-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ras, J., M. J. Hazelaar, L. A. Roberson, J. G. Kuenen, R. J. M. Van Spanning, A. H. Stouthamer, and N. Harms. 1995. Methanol oxidation in a spontaneous mutant of Thiosphaera pantotropha with a methanol-positive phenotype is catalysed by a dye-linked ethanol dehydrogenase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 127159-164. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ras, J., W. N. Raijnders, R. J. Van Spanning, N. Harms, L. F. Oltmann, and A. H. Stouthamer. 1991. Isolation, sequencing, and mutagenesis of the gene encoding cytochrome c553i of Paracoccus denitrificans and characterization of the mutant strain. J. Bacteriol. 1736971-6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusch, D. B., A. L. Halpern, G. Sutton, K. B. Heidelberg, S. Williamson, S. Yooseph, D. Wu, J. A. Eisen, J. M. Hoffman, K. Remington, K. Beeson, B. Tran, H. Smith, H. Baden-Tillson, C. Stewart, J. Thorpe, J. Freeman, C. Andrews-Pfannkoch, J. E. Venter, K. Li, S. Kravitz, J. F. Heidelberg, T. Utterback, Y.-H. Rogers, L. I. Falcón, V. Souza, G. Bonilla-Rosso, L. E. Eguiarte, D. M. Karl, S. Sathyendranath, T. Platt, E. Bermingham, V. Gallardo, G. Tamayo-Castillo, M. R. Ferrari, R. L. Strausberg, K. Nealson, R. Friedman, M. Frazier, and J. C. Venter. 2007. The Sorcerer II global ocean sampling expedition: Northwest Atlantic through Eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 5e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 37.Sorokin, D. Y., Y. A. Trotsenko, N. V. Doronina, T. P. Tourova, E. A. Galinski, T. V. Kolganova, and G. Muyzer. 2007. Methylohalomonas lacus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Methylonatrum kenyense gen. nov., sp. nov., methylotrophic gammaproteobacteria from hypersaline lakes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 572762-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sy, A., E. Giraud, P. Jourand, N. Garcia, A. Willems, P. de Lajudie, Y. Prin, M. Neyra, M. Gillis, C. Boivin-Masson, and B. Dreyfus. 2001. Methylotrophic Methylobacterium bacteria nodulate and fix nitrogen in symbiosis with legumes. J. Bacteriol. 183214-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 224673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vangnai, A. S., and D. J. Arp. 2001. An inducible 1-butanol dehydrogenase, a quinohaemoprotein, is involved in the oxidation of butane by “Pseudomonas butanovora.” Microbiology 147745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vangnai, A. S., D. J. Arp, and L. A. Sayavedra-Soto. 2002. Two distinct alcohol dehydrogenases participate in butane metabolism by Pseudomonas butanovora. J. Bacteriol. 1841916-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Spanning, R. J., C. W. Wansell, T. De Boer, M. J. Hazelaar, H. Anazawa, N. Harms, L. F. Oltmann, and A. H. Stouthamer. 1991. Isolation and characterization of the moxJ, moxG, moxI, and moxR genes of Paracoccus denitrificans: inactivation of moxJ, moxG, and moxR and the resultant effect on methylotrophic growth. J. Bacteriol. 1736948-6961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weaver, C. A., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1987. Isolation, complementation and partial characterization of mutants of the methanol autotroph Xanthobacter H4-14 defective in methanol dissimilation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1331721-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams, P. A., L. Coates, F. Mohammed, R. Gill, P. T. Erskine, A. Coker, S. P. Woods, C. Anthony, and J. B. Cooper. 2005. The atomic resolution structure of methanol dehydrogenase from Methylobacterium extorquens. Acta Crystallogr. D 6175-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson, S. M., M. P. Gleisten, and T. J. Donohue. 2008. Identification of proteins involved in formaldehyde metabolism by Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiology 154296-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia, Z., W. Dai, Y. Zhang, S. A. White, G. D. Boyd, and F. S. Mathews. 1996. Determination of the gene sequence and the three-dimensional structure at 2.4 angstroms resolution of methanol dehydrogenase from Methylophilus W3A1. J. Mol. Biol. 259480-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]