Abstract

We used wild-type UTEX481; SF33, a shortened-filament mutant strain that shows normal complementary chromatic adaptation pigmentation responses; and FdBk14, an RcaE-deficient strain that lacks light-dependent pigmentation responses, to investigate the molecular basis of the photoregulation of cellular morphology in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon. Detailed microscopic and biochemical analyses indicate that RcaE is required for the photoregulation of cell and filament morphologies of F. diplosiphon in response to red and green light.

Complementary chromatic adaptation (CCA) is a light-dependent acclimation process used by some cyanobacteria that results in optimal growth and development in response to changes in the ambient light environment (reviewed in reference 20). This process is most readily identified by observing changes in cell color between brick red and blue-green due to variations in the prevalence of green and red wavelengths in ambient light. These pigmentation changes result from the reconfiguration of the light-harvesting complexes and allow cyanobacteria to finely tune light absorption to the predominant wavelengths of ambient light and thereby maximize photosynthesis (6). CCA in the cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon (also called Calothrix sp. strain PCC 7601) has been most extensively characterized.

The pigmentation changes that are characteristic of CCA are controlled by phytochrome-related photoreceptor RcaE in F. diplosiphon (18, 27). RcaE is a sensor-kinase-class protein that contains an N terminus related to the chromophore-binding domain of phytochromes and a C-terminal histidine kinase domain (14, 18). Higher-plant phytochromes are red/far-red reversible photoreceptors that control numerous aspects of light-dependent growth and development, including seed germination, flowering, and senescence (for a recent review, see references 8 and 28). RcaE has been shown previously to exist as a chromophorylated biliprotein that is required for responsiveness to green light (GL) and red light (RL) (18, 27). RcaF and RcaC are response regulators that are proposed to act downstream of RcaE; together, these three components are predicted to form a complex phosphorelay system that regulates the transcriptional changes necessary for altered pigmentation during CCA (17, 20).

The characterized CCA response in F. diplosiphon consists of changes in cell and filament morphologies, in addition to the readily observable pigmentation changes that arise under varying light conditions (4). RL-grown vegetative cells of the F. diplosiphon UTEX481 wild-type (WT) strain are smaller and more rounded than the longer, cylindrical vegetative cells that are observed under green-enriched fluorescent illumination (4). UTEX481 WT filaments grown in RL are shorter than those grown in green-enriched fluorescent light: in a previous study, filaments grown in green-enriched fluorescent light were ∼9.2 times longer than and contained about four times as many cells as RL-grown filaments (4). Light-dependent filament length changes in F. diplosiphon slightly precede the changes observed in the levels of phycobiliproteins—e.g., in response to RL, the lengths of filaments previously adapted to green-enriched light decrease just prior to a measurable decrease in GL-inducible phycoerythrin (PE) content and an inverse increase in RL-inducible phycocyanin (PC) content (4).

The regulation of light-dependent hormogonium differentiation, a distinct photomorphogenic response in F. diplosiphon, has been shown previously to occur via a regulatory process different from the photoregulation of phycobiliprotein levels that is characteristic of CCA in this organism (12). The differentiation of hormogonia and heterocysts has been attributed previously to the differential excitations of the photosystems by GL and RL, which differ from the effects of GL and RL on CCA (7). In the present study, we investigated whether the CCA-associated changes in vegetative cell and filament morphologies are controlled by the Rca system or a distinct photoregulatory system. Here, we examine the molecular basis of the observed light-dependent morphological changes through microscopic and biochemical analyses of WT and RcaE-deficient F. diplosiphon strains.

Methods.

The F. diplosiphon strains used in these experiments were grown at 28°C in BG-11 medium (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) with 10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, and subjected to shaking at 175 rpm either with or without 20 μg of kanamycin ml−1. Green-enriched white light (GE-WL) at ∼75 μmol m−2 s−1 was provided by F20T12/PL/AQ wide-spectrum fluorescent bulbs (General Electric), and red-enriched white light (RE-WL) at ∼60 μmol m−2 s−1 was provided by Gro-Lux fluorescent bulbs (Sylvania; model no. F20T12/GRO). Broad-band GL was provided by CVG sleeved Rosco green 89 fluorescent tubes (General Electric; model no. F20T12/G78) and broad-band RL was provided by CVG sleeved Rosco red 24 fluorescent tubes (General Electric; model no. F20T12/R24) at 10 to 20 μmol m−2 s−1. Light intensities were measured using an LI-250A light meter (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) equipped with a quantum sensor (LI-COR). To determine cell culture densities, the absorbance at 750 nm (A750) was measured using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Shuttle vector pPL2.7 (10) was converted into Gateway-ready destination vector pPL2.7GW as follows: pPL2.7 was digested with HpaI and treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase. The linearized pPL2.7 vector was then ligated with Gateway conversion reading frame cassette A (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). The primers 5′ FLRcaE-GW (GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTATGAGGGATTTTGGACGCTGAGTG) and 3′ FLRcaE-GW (GGGGA<?xpp tj;2>CCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTCATTGGATATT GGCGTACTCAAG) with introduced attB1 and attB2 sites (underlined), respectively, were used to amplify rcaE with its native promoter by PCR. The PCR product was recombined into pDONR/Zeo (Invitrogen) using the BP Clonase II enzyme (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following the selection of transformants in the presence of zeocin (Invitrogen), the isolated RcaE Gateway entry clone was recombined with pPL2.7GW by using the LR Clonase II enzyme according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen) to produce expression clone pPL2.7GWRcaE. FdBk14 cells were transformed with the constructs via electroporation essentially as described previously (19).

Chlorophyll a and phycobiliproteins were extracted and analyzed effectively as described previously (15, 26). Absorbance values were used to calculate concentrations by using previously determined equations (26). The levels of phycobiliproteins were normalized to the respective levels of chlorophyll a and reported as the averages (± standard deviations) of the ratios from three independent experiments.

Soluble protein extracts were obtained as described previously (3). Total protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using the microtiter plate procedure associated with a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Clarified lysates were then concentrated using chloroform-methanol precipitation and resuspended in a mixture of 250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 15% glycerol (vol/vol), 5.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.005% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.0025% bromophenol blue (1× SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer). Concentrated protein samples (500 μg) were run on a 4 to 12.5% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel (21) and transferred onto an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

After being blocked in a solution of 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, and 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 min at room temperature, immunoblots were incubated with anti-RcaE polyclonal antibody (27) and probed with anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase according to the instructions of the antibody manufacturer (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL). Antibody was detected using SuperSignal West Dura extended-duration chemiluminescent substrate from Pierce (Rockford, IL) on an image station 2000MM multimodal imaging system (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY).

Slides of immobilized F. diplosiphon cells were prepared according to a procedure adapted from one described by Reize and Melkonian (23). Cells at a final optical density of ∼0.1 in 1.2% UltraPure low-melting-point agarose (Invitrogen) in BG-11 medium with 10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, were pipetted into a vacuum lubricant-enclosed square on 1.0-mm-thick 3- by 1½-in. Bev-L-Edge precleaned twin-frost microslides (Propper, Long Island City, NY). A 24- by 50-mm coverslip (Corning, Lowell, MA) was placed over the suspension, and slides were fixed at 4°C prior to imaging. The immobilized live cells were visualized with an inverted Axiovert 200 Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics and fluorescence excitation and emission filters. A 40×, 1.3-numerical-aperture oil immersion Plan-Neofluar objective lens or a 63×, 1.4-numerical-aperture oil immersion Plan-Apo objective lens was used for imaging, as indicated. DIC imaging was performed using the 488-nm laser. Population scanning was done via Z-series at 5-μm intervals to optimize for large data pools. Filament length and cell size measurements were made by utilizing the calibrated measurement tools of the Zeiss LSM image browser (LSMib). Initial phycobiliprotein autofluorescence was detected using settings adapted from previously described methods (25). After the spectral imaging of WT GL- and RL-grown cells to further refine the parameters for the detection of autofluorescence (data not shown), autofluorescence was collected using a 543-nm laser for excitation and emission with a 560- to 615-nm band-pass filter and a 640- to 753-nm Meta detector for GL-grown cells and with a 615-nm long-pass filter for RL-grown cells. Images were acquired from the confocal laser scanning microscope by using the LSM FCS Zeiss 510 Meta AIM imaging software.

Light-shifting experiments consisted of transferring GL-grown cells to RL growth conditions and vice versa. Prior to shifting, the cultures were normalized to an A750 of ∼0.1 and allowed to recover in broad-band GL or RL for ∼5 h. One set of flasks was kept under constant light conditions as a control, while another set was shifted to the opposite condition. Twenty-four hours postshift, cell samples were collected and prepared for DIC imaging using confocal microscopy as described above. Forty-eight hours after the initial shift, cultures were returned to their original light conditions, and cells were imaged 24 h later. Samples were also collected for whole-cell spectral scans at each time point. All sample collection was done under illumination identical to that of the final growth condition.

Characterization of the light-dependent cell and filament morphologies of WT and RcaE-deficient cells.

We grew cell cultures under green- and red-enriched fluorescent illumination to reexamine cell and filament morphologies previously reported for F. diplosiphon UTEX481 WT cells (4) and to determine these properties for SF33 cells. SF33 is a shortened-filament mutant strain derived from the UTEX481 WT (11). The shortened-filament phenotype results in the formation of colonies when SF33 is grown on plates, which facilitates the genetic manipulation of the strain. SF33 is a hormogonium- and heterocyst-deficient strain (14). However, SF33 shows normal CCA regulation of phycobiliprotein gene expression (11). Thus, we used this strain for comparative studies of the photoregulation of vegetative cellular morphology in F. diplosiphon. We gathered transmitted-light, DIC, and phycobilisome autofluorescent images to assess cell size and shape, filament length, and the number of cells per filament.

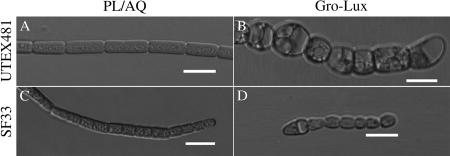

The observed shapes of UTEX481 cells were analogous to those previously reported: under GE-WL growth conditions, cells were elongated, whereas RE-WL exposure resulted in round cells (Fig. 1A and B) (4). The median filament lengths were 212.9 μm (17 cells/filament) and 52.4 μm (12 cells/filament) for UTEX481 and SF33, respectively, under GE-WL (Table 1). The median length of individual UTEX481 cells under these conditions was very similar to that reported previously, whereas the median filament length was about half that reported previously (4). Under RE-WL, UTEX481 filaments had a median length of 53.4 μm, nearly identical to that reported by Bennett and Bogorad (4), while SF33 filaments were 23.3 μm (Table 1). Both strains exhibited significantly longer filaments under GE-WL growth conditions than under RE-WL growth conditions.

FIG. 1.

Cell morphologies of the WT and SF33 F. diplosiphon strains in GE-WL and RE-WL. Representative slices from a Z-series of DIC images of WL-adapted filaments of UTEX481 (A and B) and SF33 (C and D) were captured at a 40× oil immersion lens objective. Bars, 10 μm.

TABLE 1.

Median filament lengths and numbers of cells of F. diplosiphon strains under GE-WL or RE-WL

| Straina | Filament length (μm) under:

|

No. of cells/filament under:

|

No. of examined filaments grown under:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE-WLb | RE-WLc | GE-WL | RE-WL | GE-WL | RE-WL | |

| UTEX481** | 212.9 | 53.4 | 17 | 5 | 20 | 23 |

| SF33** | 52.4 | 23.3 | 12 | 5 | 26 | 27 |

**, P < 0.001; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. The probability score indicates that the difference in filament length between GE-WL- and RE-WL-grown cultures was highly statistically significant.

GE-WL was from PL/AQ wide-spectrum fluorescent bulbs.

RE-WL was from Gro-Lux fluorescent bulbs.

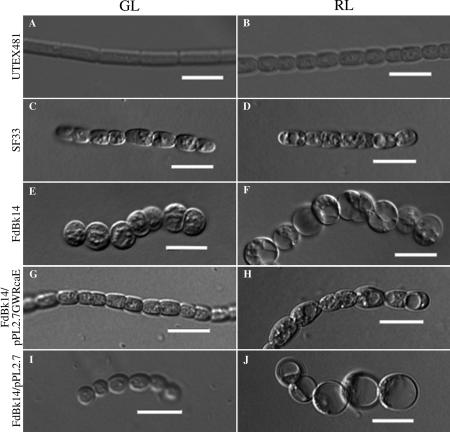

Having established the response of the cells under green- and red-enriched fluorescent illumination, we proceeded to grow cells under broad-band GL and RL, which have been identified as the light colors that result in maximal CCA, to get more insight specifically into the impact of these colors of light on the full CCA response in F. diplosiphon. As noted for GE-WL-grown UTEX481 cells, GL-grown UTEX481 cells were elongated and brick-like in shape, whereas RL-grown cells were rounded (Fig. 2A and B). However, RL-grown UTEX481 cells were not as round or as vacuolated as those grown under RE-WL (compare Fig. 1B and 2B) (4). The filaments of UTEX481 cultures grown under GL were significantly longer than the filaments of cultures grown under RL, i.e., 130.4 versus 94.6 μm (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Morphological differences between F. diplosiphon strains in broad-band GL and RL. Representative slices from a Z-series of DIC images of GL- and RL-adapted filaments of UTEX481 (A and B), SF33 (C and D), FdBk14 (E and F), FdBk14/pPL2.7GWRcaE (G and H), and FdBk14/pPL2.7 (I and J) were captured at a 40× oil immersion lens objective. Bars, 10 μm.

TABLE 2.

Median filament lengths and numbers of cells of F. diplosiphon strains under broad-band GL or RL

| Straina | Filament length (μm) under:

|

No. of cells/filament under:

|

No. of examined filaments grown under:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL | RL | GL | RL | GL | RL | |

| UTEX481* | 130.4 | 94.6 | 10 | 8 | 105 | 101 |

| SF33* | 32.0 | 26.9 | 7 | 5 | 119 | 104 |

| FdBk14 | 37.9 | 44.3 | 8 | 7 | 105 | 111 |

| FdBk14/pPL2.7 | 23.0 | 30.1 | 4 | 4 | 84 | 114 |

| FdBk14/pPL2.7GWRcaE** | 30.0 | 22.1 | 7 | 4 | 93 | 118 |

*, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.001; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. The probability scores indicate that the differences in filament length between GL- and RL-grown cultures were statistically significant and highly statistically significant, respectively.

Similar to the differences in UTEX481 measurements, we observed significant differences in SF33 cell shape and filament length between GE-WL and RE-WL conditions (Fig. 1C and D; Table 1). The difference in shape between cells grown in broad-band GL and RL, however, was less obvious. SF33 cells in GL were approximately the same length as those in RL, though cells under RL conditions were slightly more rounded (compare Fig. 2C and D). The major observed difference was the impact of GE-WL versus broad-band GL on SF33 cell shape, which may be a fluence effect or may be due to the impact of additional wavelengths of light present in the GE-WL. GL-grown SF33 filaments were significantly longer than RL-grown filaments. In GL, the median length of SF33 filaments was 32.0 μm, with seven cells per filament, whereas RL-grown filaments had a median length of 26.9 μm, with five cells per filament (Table 2). Notably, broad-band light conditions, particularly GL conditions, yielded considerably shorter filaments than green- or red-enriched light.

In comparison to the UTEX481 and SF33 morphologies described above, the FdBk14 mutant strain displayed markedly different and novel filament and cell morphologies. The filaments tended to be longer and less rigid in structure than those of the parental SF33 strain (Fig. 2E and F; Table 2). The filaments curled in the focal plane and were composed of round, bubble-like cells under both RL and GL conditions. The numbers of cells per filament in FdBk14 cultures under the two light conditions were nearly identical, and there was no statistically significant difference between the median filament lengths under GL and RL (Table 2).

RcaE regulates cellular morphology in F. diplosiphon during CCA.

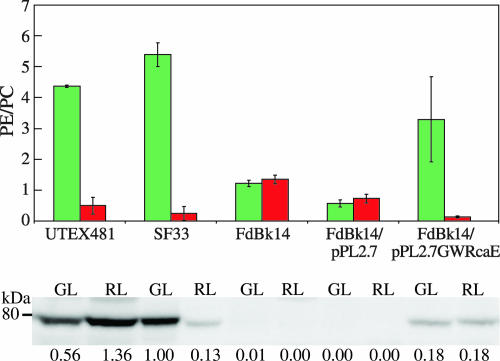

To determine whether the discernible difference in shape between SF33 cells and RcaE-deficient FdBk14 cells correlated with RcaE activity, we introduced rcaE under the control of its native promoter into the FdBk14 cell line and assessed the impact of RcaE accumulation on cell size and shape and filament morphology. Immunoblot analyses demonstrated the accumulation of RcaE in the complemented cells (Fig. 3, lower panel). The recovery of light-dependent phycobiliproteins accumulated in FdBk14/pPL2.7GWRcaE transformants indicated that the RcaE accumulating in these cells was functional: grown under RL, these cells exhibited low PE/PC ratios, whereas under GL, they had high PE/PC ratios, similar to those for SF33 cells grown under identical conditions (Fig. 3, upper panel). The accumulation of this functional RcaE was also correlated with the complementation of the rounded-cell phenotype of the RcaE null mutant (Fig. 2G and H). Although the levels of RcaE detected in UTEX481 and SF33 cells were noticeably different, the levels of RcaE accumulating in these cells did not seem to be correlated with differences in the cells' abilities to regulate PE/PC ratios in response to light. Whereas this observation does not preclude the differences in RcaE accumulation being associated with different cellular shape phenotypes, we do not believe this to be the case given the major phenotypic differences observed between GL-grown UTEX481 and SF33 cells, in which the levels of RcaE were much more similar than those in RL-grown cells, and the very similar sizes and shapes of RL-grown UTEX481 and SF33 cells, which had a much greater difference than GL-grown cells in the levels of RcaE accumulation. Notably, the shape of complemented cells was similar to the phenotype observed for SF33 cells. GL-grown cells were more cylindrical, whereas RL-grown cells were more rounded, also analogous to those shapes observed for UTEX481.

FIG. 3.

Phycobiliprotein ratios and immunoblot analysis of RcaE accumulation in WT and SF33 strains, the FdBk14 mutant, and FdBk14 transformants. Upper panel, PE/PC ratios for F. diplosiphon strains. The colors of the bars indicate the colors of the illumination under which the cells were grown, and the bars represent the averages (± standard deviations) of results from three independent experiments. Lower panel, immunoblot results for RcaE accumulation in WT cells and FdBk14 cells either untransformed or transformed with pPL2.7 or pPL2.7GWRcaE during growth in GL or RL. A molecular mass marker is indicated to the left.

GL-grown FdBk14/pPL2.7GWRcaE filaments had a median length of 30.0 μm, with seven cells per filament, and RL-grown filaments had a median length of 22.1 μm, with four cells per filament (Table 2). Thus, the filaments in GL-grown cultures were significantly longer than those in RL-grown cultures, which is consistent with the patterns observed for both the SF33 and UTEX481 strains. The FdBk14/pPL2.7 vector control cells were very similar to those of the FdBk14 parental line with regard to the round cell shape, as expected (Fig. 2I and J). Notably, the filament lengths under GL and RL conditions were not significantly different but were shorter than those of the FdBk14 strain (Table 2). Vector control cells did not show complementation of the phycobiliprotein accumulation levels under red and green illumination: PE/PC ratios in GL and RL were similar, as observed for the parental FdBk14 line (Fig. 3).

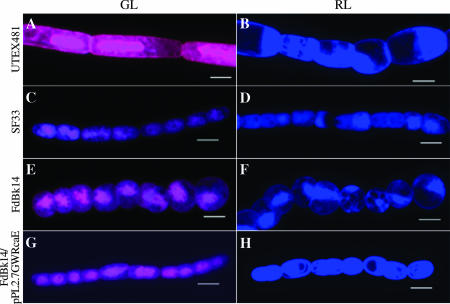

Confocal-scanning analyses enabled us to detect autofluorescence from the phycobilisomes and, thereby, to gain a more detailed view of the filament and cell structures. It also was vital to be able to visualize autofluorescence to ensure that slide preparation had not harmed the cells. For GL-grown filaments, we used a band-pass filter of 560 to 615 nm to observe autofluorescence, indicated by a pink color (Fig. 4, left panels), which correlated with the accumulation of GL-inducible PE, as well as the Meta scanning filter from 640 to 753 nm to observe autofluorescence from allophycocyanin, indicated by a blue color (Fig. 4, left panels). For RL-grown filaments, we used a 615-nm long-pass filter to observe autofluorescence, indicated by a blue color (Fig. 4, right panels), which correlated with the accumulation of RL-inducible PC, as well as constitutive PC and allophycocyanin. In our autofluorescence images, the differences in cellular morphology between WT and RcaE-deficient strains were more apparent than in our earlier observations.

FIG. 4.

Phycobiliprotein autofluorescence of F. diplosiphon strains in broad-band GL and RL. Maximum-projection images from a Z-series of images of GL- and RL-adapted filaments of UTEX481 (A and B), SF33 (C and D), FdBk14 (E and F), and FdBk14/pPL2.7GWRcaE (G and H) were collected at a 63× oil immersion lens objective with a 2.5× zoom setting. Bars, 5 μm.

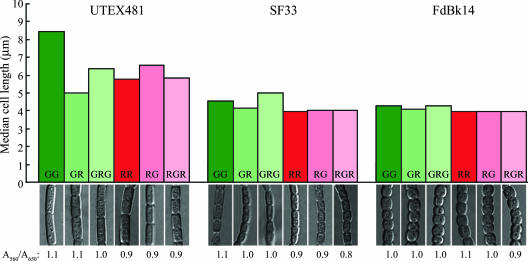

To explore further whether the light-dependent changes in cell shape were under the direct control of RcaE, we examined the impact of shifting cells from one light condition to another on cellular morphology. In these experiments, we noted that the change in shape observed for WT cells was largely photoreversible and preceded light-dependent acclimation of phycobiliprotein levels (Fig. 5). Cells of GL-grown UTEX481 cultures shortened significantly when shifted to RL (P < 0.001; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test) and elongated significantly when shifted back to GL (P < 0.001), while the ratio of A560 to A620, an estimation of the ratio of the PE content to the PC content, remained basically constant. Conversely, UTEX481 cells of RL-grown cultures elongated significantly when shifted to GL (P < 0.01) and shortened significantly when shifted back to RL (P = 0.013), again with constant A560/A620 ratios. Notably, whereas SF33 cells exhibited a significant response when shifted from GL to RL (P = 0.011) and back (P < 0.001), RL-grown SF33 cells did not display significant changes in length in response to being shifted to GL (P ≥ 0.05) and back to RL (P ≥ 0.05). Although no significant changes in length were observed, cells shifted from RL to GL were observably more cylindrical than cells kept in RL, whereas those shifted from GL to RL were more rounded than cells kept in GL, as observed for all other RcaE-containing strains (Fig. 5, lower panel). GL-grown FdBk14 cells showed only marginally significant responses to being shifted to RL (P = 0.014) and back to GL (P = 0.03), and RL-grown cells showed no significant response to being shifted to GL (P ≥ 0.05) and back to RL (P ≥ 0.05). The marginal responses observed for GL-grown FdBk14 cells upon being shifted to RL and returned to GL were markedly weaker than the responses observed for the SF33 parent. Taken together, these data indicate that RcaE controls the light-dependent changes in cellular morphology in F. diplosiphon, in addition to the steady-state acclimation of phycobiliprotein levels during CCA.

FIG. 5.

Median cell lengths and cell morphologies of F. diplosiphon strains in light-shifting experiments. Upper panel, bars represent the median cell lengths (in micrometers) calculated for a data set of at least 100 cells measured for UTEX481, SF33, and FdBk14 strains. Cultures were maintained in constant green (GG) or red (RR) light or shifted from GL to RL (GR) before being shifted back to GL (GRG) or shifted from RL to GL (RG) before being shifted back to RL (RGR). Lower panel, representative slices from a Z-series of DIC images collected at a 40× oil immersion lens objective with a 3× zoom setting. Numbers below the images are the ratios of A560 to A620 and are reported as an estimation of the ratios of PE to PC.

As our results indicate that RcaE is involved in the photoregulation of cell and filament morphologies in F. diplosiphon, we investigated whether this RcaE-dependent morphological response was being transmitted via the known RcaE-RcaF-RcaC signal transduction pathway (reviewed in reference 20). We examined the cell shapes of rcaF (FdR101) and rcaC (FdR102) mutants that we isolated as pigmentation mutants after heat shock of SF33 cells by an established protocol (2) to determine whether these mutants exhibited phenotypes similar to that of the RcaE-deficient FdBk14 mutant. Because rcaF and rcaC mutants exhibit constitutive accumulation of GL-inducible PE under either GL or RL growth conditions (9, 17) and, thus, the Rca pathway is likely fixed in the GL mode in these mutants, our observation that cells of the FdR101 and FdR102 mutants grown in either GL or RL were nearly identical in appearance to GL-grown SF33 cells was not unexpected (J. R. Bordowitz and B. L. Montgomery, unpublished data).

In summary, our results indicate that RcaE has a regulatory role in the light-dependent changes in cell shape and filament morphologies in F. diplosiphon. The photoreceptor RcaE had already been shown to regulate the light-dependent phycobiliprotein changes that occur as part of CCA (18, 27). Although light-dependent changes in vegetative cell morphology previously had been noted to respond to red and green illumination (4), the molecular basis of the photoregulation of cell and filament morphologies for F. diplosiphon had not been determined definitively, though the photoregulation was proposed to be directly or indirectly controlled by a photoreceptor(s) (4). Thus, the finding that RcaE is the photoreceptor responsible for regulating these responses demonstrates a novel role for the phytochrome-like protein RcaE in this organism and provides a molecular link for the pigmentation and morphological aspects of CCA first documented over 30 years ago.

Phytochromes have been implicated previously in the regulation of development and cellular morphology in a range of organisms from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. Such phytochrome-associated regulation of development includes growth responses, cell shape and filament morphology, sexual development, and cell elongation and expansion (1, 5, 13, 16, 22, 24, 28). Thus, the association of RcaE activity with the light-dependent regulation of vegetative cell shape and filament morphology in F. diplosiphon that we describe here is not serendipitous for a phytochrome-related protein.

The regulation of phycobiliprotein accumulation during CCA is dependent upon the Rca system. An inability to induce the RL-dependent cellular phenotype in rcaF and rcaC mutants suggests that functional RcaF and RcaC are required for the correct regulation of cell shape in F. diplosiphon, at least in response to RL (Bordowitz and Montgomery, unpublished). Such red mutants have previously been thought to disrupt phosphorelay from the kinase-active state of RcaE and thus exhibit phenotypes associated with RcaF and RcaC in their unphosphorylated states (17). Collectively, these results suggest that RcaE regulates cell shape and filament length via the downstream effectors RcaF and RcaC in response to RL. Whether the kinase activity of RcaE and the subsequent phosphorelay to RcaF and RcaC are required absolutely for the photoregulation of cell and filament morphologies and whether additional effectors are required for responsiveness to GL are questions currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Michigan State University (Barnett Rosenberg Endowed Fellowship to J.R.B), by a CAREER award from the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB-0643516 to B.L.M.), and by the U.S. Department of Energy (grant no. DE-FG02-91ER20021 to B.L.M.).

We thank Andrea Busch and Sankalpi Warnasooriya for critically reading the manuscript. We are grateful to Melissa Whitaker for technical assistance. Also, we thank Melinda Frame of the MSU Center for Advanced Microscopy for assistance with confocal microscopy, Karen Bird for editorial assistance, and Marlene Cameron for assistance with figures.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamec, F., D. Kaftan, and L. Nedbal. 2005. Stress-induced filament fragmentation of Calothrix elenkinii (cyanobacteria) is facilitated by death of high-fluorescence cells. J. Phycol. 41835-839. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvey, R. M., J. A. Karty, E. Roos, J. P. Reilly, and D. M. Kehoe. 2003. Lesions in phycoerythrin chromophore biosynthesis in Fremyella diplosiphon reveal coordinated light regulation of apoprotein and pigment biosynthetic enzyme gene expression. Plant Cell 152448-2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balabas, B. E., B. L. Montgomery, L. E. Ong, and D. M. Kehoe. 2003. CotB is essential for complete activation of green light-induced genes during complementary chromatic adaptation in Fremyella diplosiphon. Mol. Microbiol. 50781-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, A., and L. Bogorad. 1973. Complementary chromatic adaptation in a filamentous blue-green alga. J. Cell Biol. 58419-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenstein, A., K. Vienken, R. Tasler, J. Purschwitz, D. Veith, N. Frankenberg-Dinkel, and R. Fischer. 2005. The Aspergillus nidulans phytochrome FphA represses sexual development in red light. Curr. Biol. 151833-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, D. 1996. Complementary chromatic adaptation alters photosynthetic strategies in the cyanobacterium Calothrix. Microbiology 1421255-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, D., J. Houmard, and N. T. De Marsac. 1993. Electron transport regulates cellular differentiation in the filamentous cyanobacterium Calothrix. Plant Cell 5451-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, M., J. Chory, and C. Fankhauser. 2004. Light signal transduction in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. 3887-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang, G. G., M. R. Schaefer, and A. R. Grossman. 1992. Complementation of a red-light-indifferent cyanobacterial mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 899415-9419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiang, G. G., M. R. Schaefer, and A. R. Grossman. 1992. Transformation of the filamentous cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon by conjugation or electroporation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 30315-325. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobley, J. G., E. Zerweck, R. Reyes, A. Mody, J. R. Seludo-Unson, H. Jaeger, S. Weerasuriya, and S. Navankasattusas. 1993. Construction of shuttle plasmids which can be efficiently mobilized from Escherichia coli into the chromatically adapting cyanobacterium, Fremyella diplosiphon. Plasmid 3090-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damerval, T., G. Guglielmi, J. Houmard, and N. T. De Marsac. 1991. Hormogonium differentiation in the cyanobacterium Calothrix: a photoregulated developmental process. Plant Cell 3191-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diakoff, S., and J. Scheibe. 1975. Cultivation in the dark of the blue-green alga Fremyella diplosiphon. A photoreversible effect of green and red light on growth rate. Physiol. Plant. 34125-128. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herdman, M., T. Coursin, R. Rippka, J. Houmard, and N. Tandeau de Marsac. 2000. A new appraisal of the prokaryotic origin of eukaryotic phytochromes. J. Mol. Evol. 51205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn, K., D. Mazel, J. Houmard, N. Tandeau de Marsac, and M. R. Schaefer. 1997. A role for cpeYZ in cyanobacterial phycoerythrin biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 179998-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakiuchi, Y., T. Takahashi, A. Murakami, and T. Ueda. 2001. Light irradiation induces fragmentation of the plasmodium, a novel photomorphogenesis in the true slime mold Physarum polycephalum: action spectra and evidence for involvement of the phytochrome. Photochem. Photobiol. 73324-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehoe, D. M., and A. R. Grossman. 1997. New classes of mutants in complementary chromatic adaptation provide evidence for a novel four-step phosphorelay system. J. Bacteriol. 1793914-3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kehoe, D. M., and A. R. Grossman. 1996. Similarity of a chromatic adaptation sensor to phytochrome and ethylene receptors. Science 2731409-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kehoe, D. M., and A. R. Grossman. 1998. Use of molecular genetics to investigate complementary chromatic adaptation: advances in transformation and complementation. Methods Enzymol. 297279-290. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kehoe, D. M., and A. Gutu. 2006. Responding to color: the regulation of complementary chromatic adaptation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57127-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazaroff, N., and J. Schiff. 1962. Action spectrum for developmental photo-induction of the blue-green alga Nostoc muscorum. Science 137603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reize, I. B., and M. Melkonian. 1989. A new way to investigate living flagellated/ciliated cells in the light microscope: immobilization of cells in agarose. Bot. Acta 102145-151. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson, B. L., and J. H. Miller. 1970. Photomorphogenesis in the blue-green alga Nostoc commune 584. Physiol. Plant. 23461-472. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha, R. P., P. Richter, J. Faddoul, M. Braun, and D. P. Hader. 2002. Effects of UV and visible light on cyanobacteria at the cellular level. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 1553-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tandeau de Marsac, N., and J. Houmard. 1988. Complementary chromatic adaptation: physiological conditions and action spectra. Methods Enzymol. 167318-328. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terauchi, K., B. L. Montgomery, A. R. Grossman, J. C. Lagarias, and D. M. Kehoe. 2004. RcaE is a complementary chromatic adaptation photoreceptor required for green and red light responsiveness. Mol. Microbiol. 51567-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, H. 2005. Signaling mechanisms of higher plant photoreceptors: a structure-function perspective. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 68227-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]